XI

BRUNFELS’S BOOK

1500—1550

FOR EARLY HUMANISTS, such as Teodoro of Gaza, the editing of classical texts by Pliny and Dioscorides was an end in itself. Repelled by the scholasticism of the Middle Ages and its obsession with logic and theology, the humanists saw the Middle Ages as an unfortunate hiccup between the great achievements of the classical past and the glorious promise of the secular present. They cared as much about man and his association with the living world as they did about his relationship to God. But the early scholars all agreed that if they were to understand classical authors correctly they had to produce accurate texts. Diligently comparing different versions of the classics, they restored lost passages, corrected wrong transcriptions, always attributing errors to the ravages of time, the copyists, never criticising the classical authors themselves. But when Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453, this rich source of supply for Greek texts came to an abrupt end. ‘The fount of the Muses is dried up for evermore,’ proclaimed Cardinal Piccolomini to Pope Nicholas. Denied the distraction of fresh material, the next generation of scholars began to look more critically at the accumulated body of work newly translated into Latin. They dared question the fabled authorities. Nicolo Leoniceno published his Indications of Errors in Pliny; Ermolao Barbaro brought out his Castigationes. A thorough grounding in the classics was the standard apprenticeship for a humanist scholar but they soon began to find that the texts raised more questions than they answered. The Arab intermediaries, who had done so much to keep the old Greek texts alive, were now suspect. How much of their own thinking and writing had they interpolated into the hallowed texts of Dioscorides and Pliny?

Gradually, scholars began to untie the knots that bound them to the ancient texts. Looking back from our impatient age, full of arrogance, crammed with knowledge of things that had yet, then, to be discovered, we wonder why it took them so long. The humanists, after all, cultivated delight in nature, and insisted that it be understood and enjoyed for its own sake, not (as St Augustine had instructed) for its value in interpreting the Bible or as an allegory of the wonders of God. It was time for emancipation. It was time for original thinking.

It was time to look at the plants themselves, rather than what had been written about them 1,700 years previously. But the thinking could only happen after the looking. Fortunately, the opportunities to look at plants increased substantially in the sixteenth century as the first botanic gardens were established in Padua and Pisa, the first examples of the hortus siccus (collections of pressed, dried plants) were made and, above all, when the first quasi-serious books on plants were published. The first was Otto Brunfels’s Herbarum vivae eicones (1530) and as the title (Living Portraits of Plants) suggests, the pictures in it are more important than the words.

In his Dedication, Brunfels (1488-1534) (see plate 58) wrote that he had no other end in view than bringing back to life ‘a science almost extinct. And because this has seemed to me only possible by thrusting aside all the old herbals, and publishing new and really lifelike illustrations, and along with them accurate descriptions extracted from ancient and trustworthy authors, I have attempted both; using the greatest care and pains that both should be faithfully done.’1

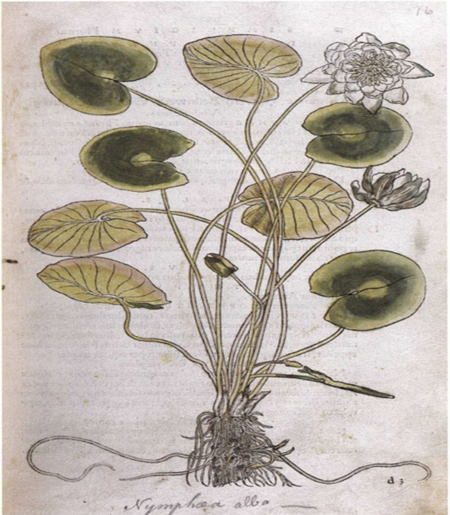

Brunfels’s illustrator was Hans Weiditz and with his ‘new and really lifelike illustrations’ Weiditz laid down a series of images of plants that meant that nobody need ever question again what a pasque flower looked like. Or a narcissus. Or an alchemilla. Or a water lily (see plate 62). Amadio had done that too (with a much more limited range of plants) but his paintings were one-offs. Here was a process that made it possible for scholars in Germany, France, Italy, Denmark, all to look at exactly the same image. The iconography of plants had begun. There was still a vast swamp to wade through before scholars agreed on the labels that should be attached to the icons, but Weiditz, who had been a pupil of Dürer’s, provided 260 superbly lifelike plant portraits. He showed the broken stem of a teasel, the wilted leaves of a hellebore, the disease attacking the green leaves of his wild orchid. These were faithful images of individual specimens, not vague representations of types.

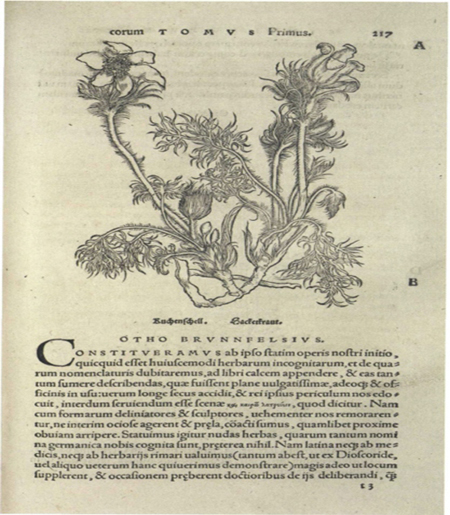

In his long Dedication, Brunfels does not mention Weiditz by name. He gets his credit, ‘meyster Hans Weyditz von Strassburg’, in the author’s Introduction to the German language edition, the Contrafayt Kreuterbuch published two years later. Brunfels seems to resent rather than applaud the illustrator’s extraordinary achievement. He complains that on many occasions he has had to give way ‘to the masters and journeymen-engravers’ because they drew what they liked, when they liked. He explains that he hasn’t been able to arrange the plants in any meaningful way because he only knew what was to be included when the block-cutters produced the images. The book was published in separate parts as sufficient material was gathered together; the first volume, which came out in 1530, was followed by a second in 1531-2 and a third, published posthumously, in 1536. From our perspective, we recognise Weiditz’s pictures as being much more significant than Brunfels’s text, but perhaps it was like this from the beginning. Perhaps the book was not Brunfels’s idea at all but was instigated by his printer/publisher Johannes Schott of Strasbourg. Perhaps Schott saw an untapped market for a new, well-illustrated book on plants, commissioned Weiditz and throughout treated him as the most important contributor to the enterprise. Forty-seven of the plants that Weiditz chose to paint had never been illustrated before. They included common but beautiful native plants such as wood anemone, lady’s smock, plantain, and the pasque flower, which inspires one of the most beautiful images in the entire book (see plate 59): the featheriness of the foliage, the soft hairiness of the stems, the flowers opening above a ruff of tendrillike growths, all caught to perfection by Weiditz. Brunfels was extremely grumpy about including the pasque flower, a ‘herba nuda’ with no proper Latin name, useless to apothecaries. The wood anemone was similarly dismissed as a wildwood herb, ‘the name of which is unknown’. On the lily-of-the-valley, another wild flower that Weiditz painted, the authorities, said Brunfels, were ‘as silent as fishes’. He didn’t see the point of including plants that had no known use. No previous writers on plants had ever done so. He wasn’t an innovator. But Weiditz, taught by the uncompromising Dürer, was evidently intrigued by the intrinsic diversity of plants, the various forms of leaves, the way a flower was positioned on its stem, the different receptacles that held seed. And because Weiditz produced these new images, which were then printed and distributed all over Europe, the plants he showed could no longer be ignored. Apothecaries may have had no use for them, but they existed, these ‘herbae nudae’, these no-name nonentities. In 1530, when the first part of Herbarum vivae eicones was published, there simply weren’t enough plants in the pool to make sorting and categorising a viable exercise. Even so, Brunfels felt he ought to be imposing some order. He was irritated when he had to accept a plant name he didn’t recognise simply because it was the name the artist had used (’Huic flori nomen inditum a grapheo accepimus cum pingeret’).2

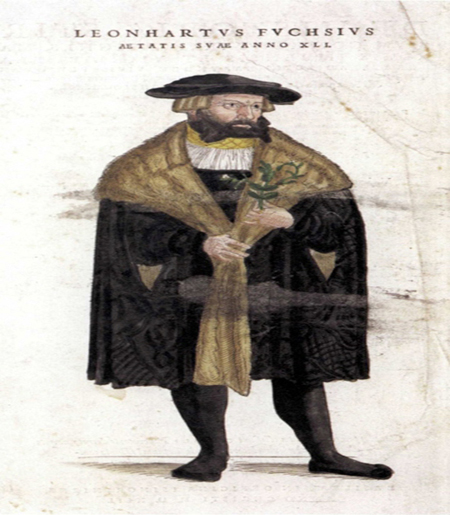

Plate 58: Otto Brunfels (1488-1534), author of Herbarum vivae eicones (1530-36), illustrated by Durer’s brilliant pupil, Hans Weiditz

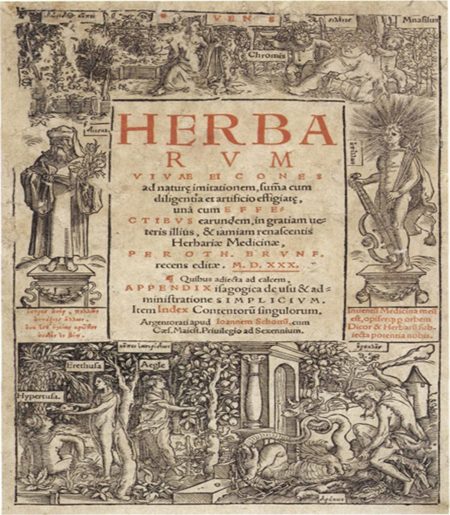

Brunfels’s text was drawn together from all the usual sources. There were forty-seven of them and they included Theophrastus, Dioscorides, Pliny, Apuleius Platonicus and Arab physicians such as Serapion, Mesue, Avicenna and Rhazes. The elaborate frontispiece (see plate 60) is crammed with classical allusion: Dioscorides and Apollo (in a strange tasselled cloak) are set on plinths either side of the framed title, Venus relaxes in a sixteenth-century garden of raised beds, set round with boards, and the Hesperides frolic below in their orchard of golden apples. But Brunfels also gave credit to what he called the vulgus, as opposed to the docti. He has respect for their practical knowledge of plants, ‘qui non ex libris sapiebant, sed experientia rerum edocti erant’.3 It was the herb-women, the ‘vetulas expertissimas’ who told him about the spinach-like pot herb Good King Henry (’Praeterea et earn adpinximus quae vulgo Guot Heinrich vocatur, vel Schwerbel. Itsenim vetulae nos persuaserunt’).4 And he seems to take grim satisfaction in telling the story of a dinner given early in the sixteenth century by the physician-humanist Guillelmus Copus of Basel. Copus pulls a herb out of the freshly served salad and asks his guests, fellow physicians from the Paris faculty of medicine, if they know its name. None of them does and they suppose it to be a very rare exotic. Copus calls in the kitchen maid who tells them it is parsley.

Plate 59: The pasque flower (Pulsatilla vulgarisj, one of the ‘herbas nudas’ that Otto Brunfels reluctantly included in his Herbarum vivae eicones (1530-36)

Brunfels’s own background perhaps gave him this natural empathy with the vulgus. He was born at Braunfels, near Wetzlar in Germany. His father, John, was a cooper, and strongly opposed his only son’s desire to enter the Church. Around 1510 Brunfels took a Master of Arts degree at the University of Mainz, left home and became a noviciate in a Carthusian monastery at Konigshofen near Strasbourg. He stayed there for about ten years but then, having converted to the Lutheran cause, escaped with a fellow priest, Father Michael Herr, and was taken in by the printer, Johannes Schott in Strasbourg. For the next couple of years, he travelled through south-western Germany, preaching as an evangelical Lutheran. When he returned to Strasbourg in 1524, he married and set up a school. For the next ten years everything he wrote and published was on theology, until in 1532, he took a degree as Doctor of Medicine at the University of Basel. He practised briefly in Strasbourg before becoming city physician in Bern. Only a year later, he died of consumption.

So he did most of the work on Herbarum vivae eicones when he was also running his own school and after a life dominated by theology. He gained his doctor’s degree in 1532, the year in which the second volume of Herbarum vivae eicones was published. His course of study would have included lectures on res herbaria, the only way then available for a student to learn about plants. His teachers would have shown him how to navigate his way through the standard texts, gobbets of which he then regurgitated in the Herbarum. But this subject matter was almost as unfamiliar to him as it was to his readers. And it was restricted. His teachers at Basel would have been lecturing only about plants of medicinal value. No wonder he was irritable when Weiditz presented him with pictures of plants on which the classical authors had nothing to say. If they were ‘silent as fishes’ then he too was forced to be dumb, unless he could pick up information from local herb-gatherers or apothecaries. Uncritically, he accepts the ‘doctrine of signatures’, which laid down that the appearance of a plant was the best clue as to its use. Polygonum, for instance, was widely used to heal flesh wounds because of the blood-red blotch on each of its leaves. ‘This herb,’ wrote Brunfels, ‘is also of two kinds, large and small, but both have a peach-like leaf which is blotched in the middle, just as if a drop of blood had dripped on to it, a mighty and marvellous sign which astonishes me more than any other miracle of the herbs.’ Where a group of plants is in a muddle, with all kinds of disparate things lumped together as if they were different manifestations of the same flower, Brunfels replicates the mess, without adding any observations of his own. On narcissus he writes:

Plate 60: The title page of Herbarum vivae eicones by Otto Brunfels, which included superb illustrations of plants by Hans Weiditz. It was published in Strasbourg in 1530

There are, they say, two kinds of flower, namely, male and female, purple, yellow and white; also it flowers twice in the year, once in March and then in September; it sheds its seeds at Whitsuntide, and in the beginning of the year forsooth it springs up with white and yellow flowers, and in the winter with purple ones. They say that they have caught it in a miracle of nature; for if anyone tried to dig it up in March he could easily uproot it with a single finger, but from that time onwards it settles down daily deeper and deeper into the ground until September, when it can scarcely be dug up without a great deal of trouble. In the meantime, it lurks in the earth at the depth of one cubit, but in the winter it soon moves upwards again, so that it comes out even above the ground with its first bloom at the breath of spring. We also have found this, and have observed that the root is at first soft and bulbous and the leaves are like those of Porrum [leek] …, but soon the root hardens, and the leaves become more fleshy, coming from the root without a stalk. From September onwards it is quite hard and very deeply barked, but with a rather delicate and lily-like flower, opening about a hand’s breadth above the ground, after the second mowing of the meadow.5

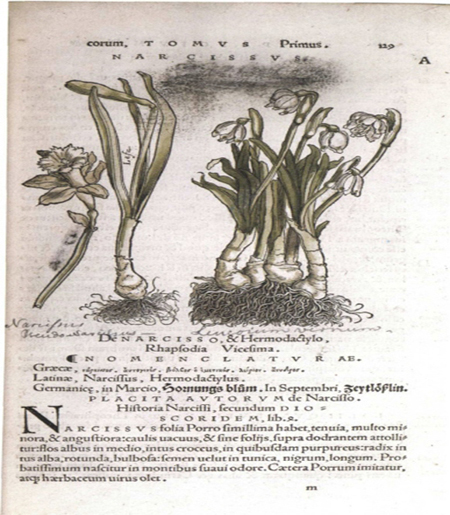

In fact there are three plants fighting to get out of this capacious hold-all: the yellow-flowered daffodil, the white-flowered spring snowflake and the purple-flowered colchicum or autumn crocus. Weiditz’s illustrations of the daffodil and snowflake, set together on folio 129 of the first volume of the Herbarum (see plate 61), show that the flowers are entirely different. And in the list of names (Greek, Latin and German) that Brunfels gathers under his Nomenclaturae, he shows that in Germany, at least, the plants are known by two completely different common names. The March flower is called ‘Hornungsblum’, the September one ‘Zeytloesslin’.

Though he uses the terms ‘male’ and ‘female’, it’s not in our sense. There was still no understanding that plants had a sex life. These were just ways of distinguishing forms of plants which scholars such as Brunfels believed to be basically the same. The ‘male’ term was often used to separate dark flowers from pale ‘female’ ones. So Brunfels’s male ‘narcissus’ would be the purple-flowered colchicum, his female, the white spring-flowering snowflake. He called the yellow water lily male, the white one female. Sometimes ‘male’ was used to represent what seemed to observers to be the standard, model form of a plant. ‘Female’ then became the way to describe an aberrant, though not necessarily lesser, form.

Plate 61: A wild daffodil or Lent lily (Narcissus pseudonarcissus) and a spring snowflake (Leucojum vernum) from Otto Brunfels’s Herbarum vivae eicones (1530)

Plates 62 and 63: No lifelike images of plants had appeared in a printed book until Hans Weiditz produced these illustrations for Herbarum vivae eicones (1530). They included the white-flowered water lily (Nymphaea albaj and various wild violets (Viola ssp.)

So in modern-day parlance, Brunfels did a competent ‘scissors and paste’ job, but contributed little that was new. Of the 258 species identified by Thomas Sprague in Brunfels’s Herbarum, seventy-eight were known to Theophrastus, eighty-four to Dioscorides and other writers of the classical period, and forty-nine to medieval botanists.6 The forty-seven ‘new’ plants, new only in the sense that they had not found themselves in a book before, seem to have been chosen by Weiditz for their looks, rather than by Brunfels for their scientific value. We can excuse him for not arranging the plants in any logical order as Schott, the publisher, who had spent a good deal of money in commissioning the engravings, evidently did not want to wait until the entire body of work was complete. As soon as he had a decent number of illustrations, he published them. Brunfels, though, could at least have devised some logical system for naming plants, but he didn’t. He prefers a ‘classical’ name, if he can find one in his sources; if not, he chooses fairly indiscriminately from a variety of common names. That the ancient authors were mostly describing Mediterranean plants and knew very little about the native plants of transalpine Germany seems to him an impossible concept. If he has to deal with a German native plant that doesn’t appear in the works of Theophrastus or Dioscorides, he dismisses it. Or he supposes that the plant must once have been known to the ancients, but that their descriptions of it have been misconstrued by perfidissimi corruptores. He doesn’t bother with much description, but given such brilliant illustrations, the reader scarcely needs them. There was still no special vocabulary to describe the parts of plants. They were still characterised by comparison; the leaf of Brunfels’s polygonum is ‘peach-like’, the foliage of his narcissus is ‘like that of a leek’.

Why is the book important? Primarily because of Weiditz’s illustrations. They provided a new base line which everyone with access to the book appreciated. All over Europe, scholars recognised that here was the start of a new journey towards a full knowledge of the plant world. Printing would eventually have a profound influence on the study of plants because it was the vehicle by which identical images of them could be spread. The existence, for the first time, of a body of lifelike pictures of plants provided a vital catalyst to study them and develop some way of classifying them into meaningful groups. So, if these naturalistic illustrations had such a galvanising effect (and they did), why were they so long in coming? Part of the problem lay with the reverence humanist scholars of the early Renaissance initially held for the classical texts they were recovering; ancient authors, such as Pliny, had maintained that a picture could only show a plant in one form, which could be misleading. But Weiditz got over that by including all kinds of minutiae alongside his main portrait: next to his picture of a daffodil plant in bud, for instance, is a drawing of an open flower. Slowly, though, the long-entrenched prejudice against illustrations faded away. The advantages of including them became too obvious. A second problem was technical rather than cultural. Artists had shown that they could portray plants, but it wasn’t until Dürer’s time that there were block-cutters (sculptores) sufficiently skilled to cut these images into the wooden blocks from which prints could be produced. Dürer’s exacting demands ensured that a new tradition and craft of block-cutting was created in Germany. That is why the first decent herbals were produced by German printers and block-cutters, rather than Italian ones. Italy, seat of the Renaissance, quickly regained its pre-eminence, but in printing, Germany led the way.

Plate 64: Leonhart Fuchs (1501-1566) as he is shown in his De historia stirpium (1542)