XIII

IN ITALY

1500—1550

IT’S A SATURDAY morning, the 2nd of November, and I’m walking into Donnini from Santa Maddalena, where for the last six weeks, isolated in Italy, I’ve been trying hard to forget what I know. The two places are only a couple of miles apart and I can do the whole stretch on tracks through vineyards and olive groves, past crumbling barns and signpost cypresses without ever touching a road. The grapes have already been picked and all that’s left are the dry leaves rustling on the vines. Now they are harvesting the olives. Some of the pickers use wooden tongs which they pull down over the branchlets, liberating the olives into the nets spread under the trees. Others just run their gloved hands down over the branches, making a noise like cows grazing in new, lush grass. Big, shallow, wicker baskets heaped with olives stand by the wooden ladders, alongside tidy piles of olive prunings, the low, young growth which they cut out from each tree as they harvest it.

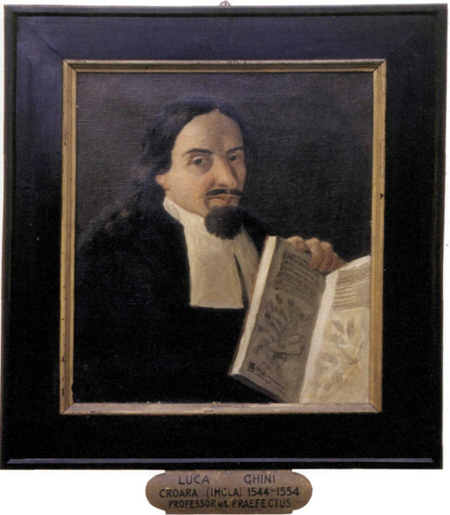

Why am I here? Why am I trying to rid my mind of concepts such as evolution and all that it entails? Because in the sixteenth century, Italy was at the heart of the great quest to explore and understand the natural world. Germany, as represented by Brunfels and Fuchs, snatches the credit for publishing the first important books on plants. But almost all the other important discoveries and innovations happened here in Italy. The Renaissance in the study of plants had already begun to flower in the fifteenth century, in the painted pages of Benedetto Rinio’s gorgeous herbal. The first edition of Pliny’s Natural History had been published in Venice in 1469. Teodoro of Gaza’s Latin version of Theophrastus came out in Treviso in 1483. The earliest commentators on Pliny and Dioscorides were Italian scholars: Ermolao Barbaro, a member of the Venetian Senate, and Nicolo Leoniceno, professor of medicine at Ferrara University. Marcello Vergilio (1464-1521) had prepared a new translation of Dioscorides’s De materia medica which appeared in 1518, when the paint on Michelangelo’s frescoed ceiling in the Sistine Chapel was scarcely dry. And why am I trying to forget what I know? Because unless I can clear my mind of all that has happened since then - Linnaeus, Darwin, DNA - I won’t be able to appreciate the scale of these achievements in Italy. The recovery of ancient learning had been the defining feature of the early Renaissance. The second half was more innovative: discovery rather than recovery. At Padua in 1533, Francesco Buonafede, the university’s former professor of medicine, became the first ever professor of simplicia medicamenta - plants for medicine. We’d call it botany, but that word hadn’t yet been invented. In the 1540s, the first botanic gardens were established at Pisa, Padua and Florence, where the Grand Duke Cosimo I of the Medici rented ground for a garden from 1 December 1545. At Pisa, the brilliant teacher, Luca Ghini (1490-1556) (see plate 79), found an entirely new way of studying plants when he made the earliest hortus siccus. By pressing plants and sticking the dry skeletons into a book, he invented the herbarium.

So I’m searching for the landscapes of their minds, walking slowly along this old cobbled track, lined with strong edging stones and made with an elegant camber that sheds rain- and flood-water into gulleys either side. Perhaps four hours’ riding would bring a Florentine out into these forests, these paved tracks. Drifting in my direction is the comfortable smell of sheep. They are huddled under a small shelter, guarded by a dog tied to a tree; when he leaps out to bark at me, the tree (an elder) shakes and makes an old bell tied in its branches ring out a loud alarm. Set into a niche is a small glazed pottery plaque of the Madonna, painted blue, white and yellow. In a little pot underneath someone has put sky-blue flowers of chicory, white daisies and toadflax in acid-drop yellow. Behind me in the distance I can still see the very tall, very narrow tower of the church whose bell I can hear from my room at Santa Maddalena. Alongside the track are mounds of red rose hips, old man’s beard, and occasional eruptions of spindle berries, the pink an extraordinary colour at this time of the year. Schiaparelli.

’Salve!’ calls a man from the top of his ladder in an olive tree. ‘Salve!’ I reply, raising an arm to return his salute. I’m contemplating Luca Ghini and the sixteenth century, but here is a man addressing me in the language of Pliny. Ghini would have known all these things, I’m thinking, as I approach the elegant low curve of a single-span, stone bridge. Underneath, the river bed is paved with huge stone slabs, making a wide disgorge for the snow melt tipping down from the mountains. I sit on a grassy bank, eat prosciutto stuffed inside a fresh white ciabatta bought at the baker’s in Donnini, pick wild apples and figs for pudding. Next to me, the pale celadon-green flower buds of the stinking hellebore are just beginning to show above the evergreen leaves. Behind, the early foliage of iris and narcissus pushes through the marbled leaves of wild arum - one of the plants that Hans Weiditz had illustrated in great detail in Brunfels’s book of 1530. Everywhere around there’s activity. But sporadic. The land here will be left alone for long periods, unlike England. There are few cows, few sheep, few arable crops. The landscape is mostly made up of vines (which have only to be pruned, and the grapes picked) and olives, which can be pruned and picked almost at the same time. Wonderfully suitable for wild flowers, I’m thinking, as I gaze out over the Valdarno. Our English arable creates too restless a system for many of them, though annuals such as cornflower and field poppy enjoy the yearly turning over of ground. Tufted tongues of wallflowers, pinks and marigolds lick out from the huge blocks of stone in the retaining wall along the track. It leads me past a farm with roosters scratching in the midden, turkeys, geese and hens in the yard and cobs of maize hanging upside down to dry in the barn. On the roof huge orange pumpkins cure in the sun. After a couple of hours, I turn back for Santa Maddalena, taking a different path through the woods. Though I can’t see them, I can hear pigs grunting softly, snuffling up acorns. The bright red berries on the butcher’s broom light up the undergrowth. Scuffling through beech leaves, I’m trying to sort out in my mind the endless feuds and vendettas between Italy’s wildly competitive city states: Milan pitted against Venice, Rome set against Florence, Naples fighting Milan, Florence battling with Pisa, which controlled its access to the sea. But then I come into a clearing where colchicums are pushing out their last flowers, and two grazing deer look up, momentarily frozen as if in a fresco, before running off into the trees. Much later, as I’m approaching Santa Maddalena, I hear the hunters, shouting to each other, blowing their horns. ‘Hi! Hi!’ I shout, to make sure they know where I am. And in this way, our calls echoing each other across the valley, I make my way to the junction of the paths, where the hunters’ rough-haired retriever bounds out, the bell round his neck ringing in a cracked, minor key.

Plate 79: A portrait of Luca Ghini (1490-1556), the charismatic teacher at the University of Pisa who inspired an entire generation of plantsmen

These long, solitary walks in the strangely undisturbed country of the Valdarno are interspersed with train rides to Florence or Arezzo. From San Ellero, a two-euro ticket brings me into the heart of Florence, where, punch-drunk with painting, I ricochet from Giotto to Michelangelo, ending up often in the church of Santa Maria Novella, one of my favourite haunts. Though begun in 1485, the Ghirlandaio frescoes in the Tornabuoni chapel (see plate 80) seem astonishingly contemporary: the easy, confident stance of the men leaning on the rampart overlooking the town, the quizzical way that people in the painted crowd look straight at you, like the old woman I met on the Donnini track, who was dragging three long sticks back to the village. The tall belltowers are entirely familiar, the hawk stooping on to a wild duck, the little hills erupting, sharp as molehills, from the landscape beyond the town. I could walk along that distant track and find similar trees, flowers, farms, pigs, hunters, vines (but not pumpkins - they were still a New World novelty when Fuchs wrote about them in the mid sixteenth century). At Santa Maria del Carmine, south of the Arno, I trawl dutifully through the art history lecture laid out in three languages on panels in front of the altar. The centrepiece is a wondrously grave thirteenth-century Madonna by the Master of Sant’Agata, surrounded by fifteenth-century frescoes worked by Masolino, Masaccio and Fra Filippino Lippi. I’m looking through Lippi’s painted door at a hill capped with tall thin cypresses, junipers, a poplar tree. From the train that brings me into Florence from San Ellero, I see just the same hills, just the same trees.

Plate 80: A detail from The Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary to Saint Elizabeth by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1485) in the Basilica Santa Maria Novella, Florence

In the Medicis’ palazzo in Via Cavour, I peer at the glowing fruit painted on Benozzo Gozzoli’s tall, limbed-up trees. Pomegranates perhaps? Pier de’ Crescenzi’s Liber cultus ruris, first published in 1471, gives detailed directions for growing pomegranates, as well as almonds, filberts, chestnuts, cherries, quinces, figs, apples, mulberries, medlars, olives, pears, plums and peaches. The fresco Gozzoli painted here for the elder Cosimo de’ Medici (1389-1464) covers three walls of the Medicis’ private chapel and shows the three kings, Gaspar, Melchior and Balthasar making their way through a strange landscape, half dream, half real (see plate 81), with vast retinues of attendants and horses and hunting dogs, even a leopard. Cosimo, the banker and statesman who established the political power of the family in Florence, was also patron of the Confraternita dei Magi of San Marco; each year, on the day of the Epiphany, they organised a procession in costume along the city’s Via Larga. The Medicis had banks in sixteen European cities and it was money, whether Roman, Venetian, Milanese or Florentine, that fuelled the Renaissance. The Medici money had come from wool and silk, for the company traded with Britain, Flanders and France, bringing in bolts of plain cloth to be reworked and dyed in the fabulous blues and crimsons I’d seen in Masaccio’s paintings at the Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno. Wool merchants, silk weavers, bankers, pharmacists were among the seven major guilds that controlled trade and the Medici metamorphosis was a classic one: from trade to money to I’uomo universale, endowed with wisdom, grace and all the other virtues that Florentines revered.

Italy’s status as a country of largely autonomous city states produced a stream of rich patrons like the Medici, scholarly themselves and concerned with promoting scholarship, not only for its own sake, but as a way of gaining yet more power and prestige. By the sixteenth century, the university at Ferrara, founded originally in 1391 by Pope Boniface IX, was being extensively funded by Alphonsus and Hercules, Dukes of Ferrara. ‘Ferrara is the city whither I would counsel any and everyone to repair who desires the most exact knowledge of plants,’ wrote Joao Rodriguez de Castello Branco (1511-1568). ‘For the Ferrarese, as if under some sort of Divine influence, are the most learned of all physicians, and most diligent in the investigations of nature.’ It was the students at Padua University who had petitioned for the special chair in simplicia medicamenta, set up in 1533, but their appeal was enthusiastically endorsed by the Senate of the Republic of Venice. The city dominated an extremely profitable trade in spices; in terms of plant knowledge, there were commercial advantages in staying ahead of the competition. Dried roots, seeds, spices to make theriacs, treacles, poultices, and tisanes came in on the ships of the greatest navy in the Mediterranean (see plate 82). In the Venetian arsenal, a new galley was produced every hundred days. Ships moved along the quays as if on a watery conveyor belt, with masts, sails, oars, stores all loaded aboard as they passed the various warehouses. All the galleys belonged to the state; fixtures and fittings were standardised so that crews could easily move from one ship to another. The Venetian state had established trading communities in Acre, Alexandria, Constantinople, Sidon and Tyre and Venetian merchants were as familiar with the geography of the Black Sea as they were with that of the Adriatic. The Ferrarese physician Antonio Musa Brasavola (1500-1555) writes of a Venetian dealer he knows, trading under the sign of a bell, ‘who never counted the cost of any enterprise’, and who imported a kind of rhubarb, both dried roots and living plants, from the banks of the River Volga.1 In the last years of the fifteenth century, Venice sent at least half a dozen galleys a year to Alexandria and Beirut and laid out more than half a million ducats in buying spices abroad.2 There were Venetian ambassadors in cities as far apart as Cairo and Isfahan. Venetian travellers reached Sumatra and Ceylon before the Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) ever rounded the Cape of Good Hope. Venetians living in London, Paris and Bruges passed back intelligence to Venetian spymasters. But these travellers, ambassadors, ships’ captains and merchants also brought in new and strange plants. In 1525, the Venetian ambassador Andrea Navagero, who had a villa in Selva and a garden of rare plants on the island of Murano, writes at length to Giovanni Battista Ramusio of the plants he has seen while travelling on horseback from Barcelona to Seville, noting the crops grown by Arab farmers. The Venetian patrician Pietro Antonio Michiel (b. 1510), travels through the whole of Italy in search of rare plants. He makes a garden of exotics on the island of San Trovaso in Venice and keeps in regular touch with a whole web of Italian plantsmen, including Luca Ghini, Luigi Anguillara (c. 1512-1570) and Ulysse Aldrovandi. Venetian ships bring him in specimens from Venetians serving in places as far flung as Constantinople and Alexandria. He gathers news, books, seeds from the French, German and Flemish travellers and merchants who pass through Venice. He has contacts in Crete, Dalmatia, the Levant. And he commissions a superb herbal with drawings by Domenico Dalle Greche.3 Such productions seem to be a Venetian speciality: Benedetto Rinio, owner of the beautiful fifteenth-century herbal with paintings by Andrea Amadio, was also a Venetian. Great Venetian landowners such as Nicolo Contarini had for a long time taken a keen and intelligent interest in plants. And it had been a Venetian, Ermolao Barbaro (1454-1493), teacher of rhetoric and poetics at Padua and Venice, Venetian ambassador to the Holy See, who had produced the Castigationes Plinianae in 1492-3 and the Corollarium Dioscorides in 1516. The sack of Mainz in 1462 hastened the spread of printing through the rest of Europe and by 1480 there were presses in more than 110 towns, fifty of them in Italy. Most of those were in Venice, which quickly established a virtual monopoly of the printing business, cultivated and protected by the state. In Venice, Florence had a formidable rival, but the Medici were more than a match for the Contarini. Nicolo Leoniceno, in his Introduction to Indications of Errors in Pliny, pays a handsome tribute to ‘the munificent Lorenzo di Medici’, calling him ‘the greatest patron of learning in this age, who, sparing no expense, has sent agents into every part of the world to collect manuscripts, so providing [himself] and other illustrious men with the most abundant means of study and the acquisition of knowledge.’4 And the same dedication to learning had prompted Lorenzo’s son, Cosimo the Great, the first Grand Duke of Tuscany, to invite Leonhart Fuchs to Pisa, which he was determined to establish as the greatest seat of learning in the land.

Plate 81: A detail from the fresco (1460) by Benozzo di Lese di Sandro Gozzoli (1420-1497) in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence

Plate 82: Venice, as it appeared to navigators of the sixteenth century

The universities - Ferrara, Bologna, Pisa, Padua, Florence - provided power bases for teachers such as Luca Ghini. But they also provided a structure within which the study of plants could grow. Not long after appointing Francesco Buonafede professor of simplicia medicamenta in 1533, the University of Padua took another pioneering step in appointing an ostensor simplicium, whose job was to lead students on guided tours round the university’s new botanic garden. In the second half of the Renaissance there was a new emphasis on looking at plants; universities were the obvious places to establish living collections which students could study. It was a collecting age: minerals, strange shells, insects, corals, stuffed birds, dried snakes’skins, pickled fish. Plants fitted well in the prevailing mania to amass, assemble, convene; nature provided plenty of plants to accumulate and the numbers were increasing all the time with the exotics coming into the country from the Near East and the New World. By the early sixteenth century, there were already extraordinary collections of plants in Italy, but they belonged to rich patrons such as the Medici, who grew pineapples from the tropics in their Florentine gardens. But the university gardens at Pisa and Padua, both established by the 1540s, were not private boasting booths. They were available to all and they included as many local plants as exotics, ‘weeds’ as well as the plants long used to supply pharmacists and apothecaries. There was a very real desire to understand the relationships between all these plants, to grasp the purpose of their myriad forms. ‘The science of plants … owing to the continual and multifarious changes taking place in nature, was always difficult,’ wrote the Florentine scholar Marcello Virgilio Adriani (1464-1521), ‘and continues to be such, even to the present; because through lapse of time, diversities of location, the changes of the season, the influences of cultivation by man, and the perpetual mobility of all nature, plants seldom present the same appearance under these varying conditions. To these difficulties imposed by nature, there are added the differences of description used by writers of different nations. The perplexities embedded in these works are very great.’5 There was a phenomenal amount of work ahead in unpicking the ‘perplexities’ but the availability, at last, of excellent pictures of plants (and, thanks to Ghini and others, of dried specimens which could be studied when the plants themselves had long disappeared underground) created a firm base for debate. It helped, too, that scholars in Germany, France, Flanders, Switzerland and Italy could communicate in a common language, Latin. Books were usually published in Latin before they were translated into vernacular languages.

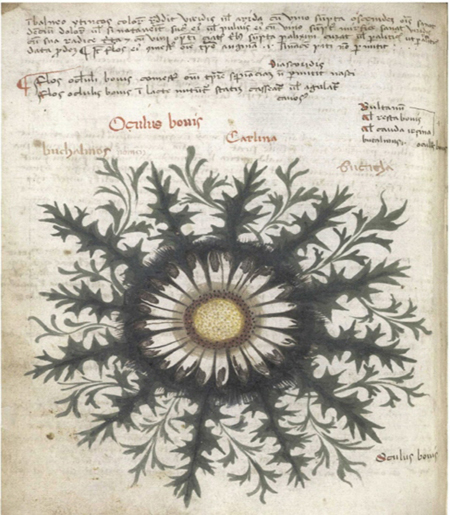

Plate 83: ‘Oculis bovis’, the carline thistle (Carlina acaulis) a common plant in the alpine pastures of Southern and Eastern Europe, in the Belluno herbal made in Italy early in the fifteenth century

But despite the pictures, despite the common language, muddles converged round even the most common of plants. In his Examen omnium simplicium medicamentorum (An examination of all plants), Brasavola of Ferrara writes, with pleasing parochial partiality, of a plant he calls Primula veris:

The Florentines make use of this herb in salads and with us, at the very beginning of spring when all herbs are tender, it is edible. But then, the soil of Ferrara produces luxuriantly so many kinds of edible herbs that this one is there neglected. This is a small herb, with leaves spreading on the ground, and a flower resembling that of camomile, and white, except that the tips of the flowers are reddish. We of the Ferrara province, where the winters are mild, see it in flower all the year round. This is what your apothecaries take to be Primula veris, by our women called petrella, by some others St Peter’s herb. Among recent names are herba paralysis and margarita, so much are people given to imposing names each according to his own fancy.6

For us, Primula veris is the official name of the spring-flowering primrose, but Brasavola’s flower, white, tipped with red, doesn’t sound in the least like a primrose. The clue lies in one of the common names he mentions - margarita. He’s talking about a marguerite, a daisy, more specifically the common daisy Bellis perennis, weed of a million lawns. This plant had been growing in Europe for as long as people had inhabited it, yet still there was no consensus about its identity. The key lay in providing universally accepted tags to set alongside the common names of plants. The common names, of course, differed from country to country; even within one country, as Brasavola demonstrated, four or five different names might be attached to the same plant. They still are. Galium aparine is an irritating, widely spread weed with stems, leaves, and peppercorn-sized fruit all covered with tiny hooked hairs. As you brush by it, the plant sticks on to you, using you as a way to spread itself about. This clinging quality gives it its common name of cleavers, but it’s also known as goosegrass, because it used to be chopped up and fed to newly hatched goslings. The common names are vivid, descriptive, and carry with them all kinds of baggage about their past. In a world that is increasingly homogenised, we see strengths in the local distinctiveness of such names. But they can’t be exported and Renaissance scholars could already see that any system they devised had to be applicable everywhere. It had to have universal validity. They had a universal language at hand, and so the simplest thing was to use this language to forge a system that, eventually, could accommodate every thing that lived on earth. In their own way, artists such as Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci had begun the process, by producing images of plants that all could recognise. The right words were more difficult to find. As Brasavola said, ‘If it were possible to understand and comprehend matters without employing words, then there would be no need of names: but neither arts nor sciences can be understood or learned without using names. Therefore, it is preferable to use the words that the best authors choose, rather than barbarous ones, approved by no authority.’7 In the Italian universities and their associated gardens, the great debate began, drawing in scholars from all over Europe. And, because the quest for order, for understanding, was a defining feature of the age, it engaged the attention of some magnificent minds.

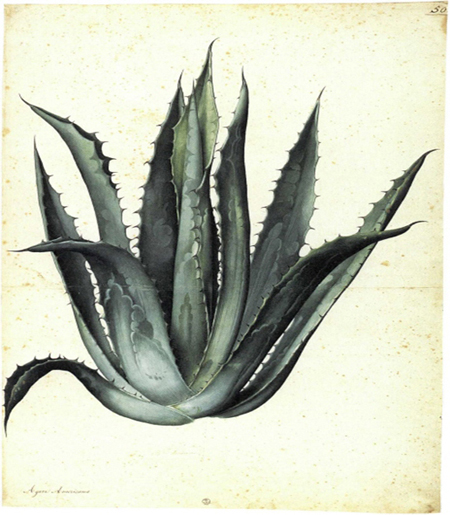

Plate 84: The American agave (Agave americana), introduced in 1561 to the botanical garden in Padua. One of a series of paintings of plants made between 1577 and 1587 by Jacopo Ligozzi (c.l547-1632) for Francesco I de’ Medici

’Look,’ I want to say to the clusters of tourists in the Uffizi, being fed their gobbets of art history by German-speaking, Japanese-speaking, French-speaking, English-speaking guides. ‘Look, it’s not just about perspective or painterly techniques or the search for symbols. My men were riding through those landscapes, discussing those trees, their provenance, their cousinships with other plants. Students were petitioning, not for courses on art history, but for information about those plants you’re looking at. By the time Botticelli died, Luca Ghini was already twenty years old. Those famous Primavera flowers aren’t just ciphers. Scholars were growing them, writing to each other about them. They are central to this new beginning.’

Scholars such as Antonio Musa Brasavola had already realised that ‘not a hundredth part of the herbs existing in the whole world was described by Dioscorides, not a hundredth part by Theophrastus or Pliny, and we add more every day.’8 By the middle of the sixteenth century, a map could be made of almost the whole world (with the important exception of Australia and New Zealand). It was now obvious that, as Sir Walter Raleigh put it, God had not ‘shut up all light of learning within the lanthorn of Aristotle’s braines’.9 In Italy, with its long, hot summers, the first successful attempts were made to cultivate many unfamiliar plants: maize, sweet potatoes, potatoes, runner beans, French beans, pineapples, sunflowers, Jerusalem artichokes. By 1550, the first tomatoes were being enthusiastically grown, not for food but for their potential as aphrodisiacs. By 1585 peppers were fruiting abundantly all over Italy, as well as in Spanish Castile and Moravia (central Czechoslovakia). Just as the revival of anatomy in Italian universities had stimulated the renaissance of medicine, so the introduction of plant studies encouraged direct observation, rational criticism, intellectual scepticism and a long-overdue questioning of classical dogma.

Plate 85: Mourning iris (Iris susianaj /rom the Lebanon, introduced to Europe in 1573 and Spanish iris (Iris xiphiumj from the Mediterranean. One of a series of paintings of plants made between 1577 and 1587 by Jacopo Ligozzi for Francesco I de’ Medici