XVI

WEAVING THE WEB

1500—1580

AT THIS WONDERFULLY fertile time, no one questioned the importance of the work at hand: the need to understand, describe, then sort and order the multifarious elements of the natural world. Like broadcasts beamed out from the first radio transmitters, the ideas debated in the Italian universities of the early sixteenth century gradually spread out over the rest of Europe. An extraordinary web of contacts was spun between scholars in Italy, France, Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands, all of whom shared the same passion for res herbaria, things to do with plants. They had no clubs or other regular places to meet. There were no scientific journals where views could be exchanged and ideas disseminated, nor societies to which like-minded people could belong.1 Nevertheless, the network spread ever wider, drawing in apothecaries, artists, clerics both Catholic and Protestant, physicians, humanist scholars and schoolmasters as well as wealthy men of leisure, their common interest in plants now stronger than the social prejudices that in previous ages might have kept them apart. Professional boundaries became blurred too. The Venetian Ermolao Barbaro had taught rhetoric and poetics at Padua and served in the Venetian Senate at the same time as producing new editions of Aristotle, Dioscorides and Pliny. Otto Brunfels had been a Carthusian monk, and a schoolmaster before he wrote his Herbarum vivae eicones. Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, responsible for introducing many superb Turkish plants into Europe, was in Turkey not as a plant collector but as Ferdinand of Austria’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. These people could be poets as well as diplomats, politicians as well as clerics, doctors as well as historians. But they were bound together by these overriding passions: the love of plants and the search for the most logical way of classifying them.

At the centre of the web were the universities, chiefly, at first, the Italian ones. The fame of the charismatic Luca Ghini spread far beyond his base at Pisa, and his successor at Bologna, Ulysse Aldrovandi, made sure that the study of plants remained at the heart of the university curriculum. Antonio Musa Brasavola (1500-1555) was equally successful in attracting students to the university at Ferrara. But soon, other inspirational teachers emerge in other universities, particularly at Montpellier, Zurich and Basel. Charles de l’Ecluse (Clusius) and Matthias de l’Obel (Lobelius), pupils of Guillaume Rondelet (1507-1566) at Montpellier, both go on to be brilliant plantsmen. In Zurich, Conrad Gesner, who had so delicately crossed swords with both Fuchs and Mattioli, has friends at Montpellier and goes plant-hunting with Jean Bauhin, who had also studied under Rondelet. Jean’s brother, Gaspard (1560-1624) is the first professor of anatomy and res herbaria at Basel University and visits scholars in Venice, Bologna, Rome, Verona and Florence. Very carefully he studies Cesalpino’s De plantis, which one of his students brings him as a present from Padua, and in 1568, writes to a friend of the difficulties of fitting Cesalpino’s plants into his own different system of classification. When, in the year before his death, he finally publishes his own book, Pinax theatri botanici, he lists sixty-three people - teachers, physicians, students, friends, correspondents - who have sent him seeds and plants.

But this web, which so intricately connected scholars across mainland Europe, did not at first include Britain. The universities at Oxford and Cambridge were slow to set up chairs for the study of res herbaria, or to establish botanic gardens to facilitate the study of plants. The Oxford Botanic Garden, the first in Britain, was not established until 1621, nearly eighty years after those at Pisa and Padua. Nevertheless some Englishmen found their way to Italy and studied res herbaria at the great universities. Thomas Linacre was attached to Henry VI’s embassy to the Vatican and had the opportunity to use the fine Vatican Library in Rome. He conferred with Ermolao Barbaro, at that time working on his new edition of Pliny’s Natural History, then moved on to Padua, where he gained his MD in 1496. By 1499, he was back in Oxford, in time to meet the Dutch humanist Erasmus, who had come to the university to study Greek. Forty years later, John Falconer is learning from Luca Ghini how to press and dry plants and stick them in a book. When Falconer shows his new hortus siccus to the Portuguese explorer Amatus Lusitanus, it is reckoned to be a marvel. Lusitanus speaks of Falconer as ‘a man fit to be compared with the most learned herbarists, a man who had travelled many lands for the study of plants and carried with him very many specimens ingeniously arranged and glued in a book’.2

Nobody in England, though, had written a decent book on plants. There was nothing that an English author could set against Fuchs’s work in Germany, or even Mattioli’s in Italy. The grete herball (see plate 100), which had been published in England in 1526, was a medieval throwback. It was no more than an English translation of a very bad French book, Le grand Herbier, dressed up with equally hopeless illustrations from a German herbal of the same period. Only in 1564, when the outspoken cleric William Turner (1508-1568) finally completed the last part of his book, A new herball, could Britain at last claim to have produced a good book on plants.

Born in Morpeth c.1508, Turner went up to Pembroke College, Cambridge, in 1526 and was awarded an MA in 1533. One contemporary describes him as ‘very handsome in person and both witty and facetious, and withal a sound and elegant scholar’, though another considered him ‘very conceited of his own worth, hotheaded, a busy body, and much addicted to the opinions of Luther’. At Cambridge he fell in with a group of reformers who met regularly at the White Horse Inn to argue about religion with the passion of new crusaders. Among them were Nicholas Ridley (c. 1500-1555), who taught Turner Greek, tennis and archery, and Hugh Latimer (c. 1485-1555), whose brilliant sermons made Cambridge a pioneering centre of the Reformation in England. The inn soon acquired a local nickname – Little Germany - because of the staunchly pro-Lutheran views of the group that met there. Like Latimer, Turner believed passionately in justice, reason and the Church’s duty to defend the oppressed. Like Latimer he argued furiously against the superstition and nepotism of the Catholic Church. Turner was scarcely ten years old when Martin Luther posted his famous Ninety-five Theses on the door of the Palace Church in Wittenburg. But Luther’s disgust at the sale of indulgences later fuelled an equally strong loathing in Turner for the corruption that was endemic in the Church in England. Cardinal Wolsey managed to get his son lour archdeaconries, a deanery, five prebends and two rectories, and was only brought to a halt when he tried to secure for him the bishopric in Durham.

Little is known about Turner’s Northumbrian background, but his life’s work, the Herball is stitched through with references to the plants that grew there and the local names by which they were known. ‘I never saw any plaine tree in Englande saving one in Northumberlande besyde Morpeth,’ he writes, ‘and an other at Barnwel Abbey besyde Cambryge.’ Speaking of wild hyacinth, ‘called in Englishe crowtoes and in the North partes Crawtees’, he remembers how ‘the boyes in Northumberlande scrape the roote of the herbe and glew theyr arrowes and bokes wyth that slyme that they scrape of’.3 But by the time the first part of the Herball was published, Turner could draw on a much wider field of reference than Northumbria and Cambridgeshire, for in 1540, unable to preach the doctrines he so passionately believed in, he fled to Calais and did not return to England until the death of Henry VIII in 1547.

Plate 100: The grete herball, published in England in 1526, was not an original work. It had been translated from a hopeless French herbal, Le grand Herbier, and was decorated with unhelpful pictures taken from a German herbal of the same period

During that long exile, sustained by generous gifts from Ridley, he wanders through France into Italy, where he studies under Luca Ghini at Bologna. He goes to Cremona, Como, Milan, and Venice, where he later writes of seeing tamarisk ‘in an yland betwene Francolino and Venish’. From Venice he proceeds to Ferrara, where he studies with Antonio Musa Brasavola ‘som tyme my master in Ferraria’. Working his way back through Switzerland, Turner visits the young Conrad Gesner, whom he describes as ‘a man most learned as most truthful’. In 1543, Turner is in Basel, a safe haven from which to launch religious tracts such as The huntying & fynding out of the Romyshe fox that he had been unable to publish in England. In the year that Mattioli brings out his Commentarii, Turner is in Cologne. There he practises medicine before moving on into Holland and East Friesland where he is appointed personal physician to ‘the Erie of Emden’. He stays four years in East Friesland, where he ‘bought two whole Porpesses and dissected them’. He dispenses bistort and feverfew to excellent effect but has a disastrous experience with opium: ‘I wasshed an achying tooth with a little opio mixed with water, and a little of the same unawares went down, within an hour after my handes began to swell about the wrestes, and to itch, and my breth was so stopped, that if I had not taken in a pece of the roote of masterwurt … with wyne, I thynck that it wold have kylled me.’ After the East Friesland adventure, he collects plants in Louvain and visits Pieter Coudenberg’s famous apothecary shop at the sign of the Old Bell in the Burgerhout at Antwerp. Writing later to Gesner, Coudenberg says, ‘I gave a sprig of Roman Worm-wood formerly to William Turner who inserted its picture in his English Herbal: but then the plant died for me without seed, nor could I for all my care recover it.’4 Moving on from Antwerp, where he first saw papyrus used as wrapping around loaves of sugar, Turner makes a diversion in order to see the pelican at Malines - a famous attraction of the age - and sends plants from Brabant to John Rich and Hugh Morgan, both apothecaries (and keen plantsmen) in the City of London. By the time he returned to England, by way of Dunkirk, he could boast (though he didn’t) that no other Englishman had seen so many different plants growing in so many different places. His capacity to assimilate and remember the details of a plant’s leaf, its stem or flower, his absorbed interest in the complex business of attaching the right names to the right species, his tireless ability to weave ever more complex links between scholars working in different languages, in different countries, but on similar casts of characters, made him a formidable confederate in an age that was full of extraordinary plantsmen. Ghini, Fuchs, Rondelet, Turner, Anguillara, Cordus, Gesner, Belon, Dodoens, Cesalpino, Aldrovandi, Clusius, Camerarius, Pena, Lobelius and Jean Bauhin were all born in the first forty years of the sixteenth century. Of course, their particular interest was not predestined. But the study of plants was the dominant preoccupation of the age. If you had a good mind, this is what you applied it to, in the same way that, in later ages, the best scientific minds turned to mathematics, nuclear physics and the search for DNA.

Plate 101: The title page of William Turner’s Libellus, printed by John By dell in 1538

Turner complained that while he had been at Cambridge, he ‘could learne never one Greke, nether Latin, nor English name, even amongest the Phisiciones of any herbe or tre, suche was the ignorance in simples at that tyme’.5 The only English book available (The grete herball of 1526) was ‘full of unlearned cacographees and falselye naminge of herbes’. Two years before his sudden departure from England, while he was still only thirty years old, he had published a little glossary of plant names, the Libellus de re herbaria (1538) which listed 144 plants with synonyms in Latin, Greek and English (see plate 101). ‘You will wonder, perhaps to the verge of astonishment,’ he wrote in his Preface, ‘what has driven me, still a beardless youth, and but slightly infected with knowledge of medicine, to publish a book on herbary.’ But, since nobody else in England seemed to want to take on the task, he thought it best to ‘try something difficult of this sort rather than let young students who hardly know the names of three plants correctly to go on in their blindness’. It was the only book Turner wrote in Latin, a modest beginning, a first attempt to untangle the tangled skein of names by which the same plant was known in different languages: ‘ATRIPLEX. Atriplex grece atraphaxis dicitur, anglice Areche aut red oreche. Atriplex hispaniensis quibusdam videtur nostra esse spinachia.’ It was the trial run for The names of herbes (see plate 102), which came out very soon after his return to England. This book includes nearly three times as many plants as the Libellus, but its prime purpose is still to match the various names by which the same plant was known in different countries in Europe. This time, Turner is able to incorporate German and French names alongside the Latin and English ones: ‘ATRIPLEX. Atriplex called in Greke atraphaxys, or Chrysolachano, in English Orech or Orege, in Duche [German] Milten, in Frenche arroches, is moyste in the seconde degree and colde in the fyrste, it groweth in gardines & in some Cornefieldes’. In Names, Turner also includes thirty-eight plants (among them alchemilla and foxglove) ‘whereof is no mention in any olde auncient wryter’. Familiar flowers had always had common names, but these of course varied, not only from country to country, but also from county to county. Often the same common name was used for different plants that had no natural relationship.

Plate 202: The title’ page of William Turner’s The names of herbes, which gathered together plant names in Greek, Latin, English, German and French. It was published in 1548

Turner had a natural aptitude for and interest in the identification of plants and their proper naming. If this was not instigated, it was at the very least massively encouraged by Ghini, who is constantly credited in Turner’s final work, the Herball, as ‘Lucas Gynus the reader [lecturer] of Dioscorides, in Bonony my maister’. There are references too to the trees and shrubs that Turner has seen on ‘Mount Appenine besyde Bonony’, including colutea, cyclamen and the Rhus which the Italians used to tan their leather. While he was in Italy he had been up the Po river as far as Milan where he saw ‘Ryse growing in plenty.’ On the road from Chertosa to Pavia he saw wonderful hops ‘growyng wylde a litle from the wall that goeth … by a little rivers syde’. At Chiavenna he had found monkshood growing ‘in great plentie upon the alpes’. From Chiavenna he had crossed into Switzerland and proceeded via Chur to Zurich and the company of Conrad Gesner. The two plantsmen remained faithful correspondents. Turner sent Gesner onions. Gesner sent Turner seed of rue. But there was still so much that was not known or understood. Turner lived in an age that believed in the existence of the phoenix, that considered a bat to be a bird. Even observers as careful as he was accepted that storks hibernated underwater on the beds of rivers. In that respect, little had changed since the thirteenth century. ‘Cocks have a very liquid brain,’ Alexander Neckham had written then in De naturis rerum. ‘In their brain there are certain bones in the top of it, very insecurely joined together. A gross vapour rising from the liquor comes out through the cracks, and because it is gross it is enclosed in the upper part of the head and forms the comb.’ In the sixteenth century it was commonly believed that gnats were generated from the dew on leaves, and that caterpillars simply appeared on cabbages. In an age that knew nothing of pollination, or metamorphosis, or migration, spontaneous generation seemed to be a reasonable explanation of nature’s mysteries, the only one that their processes of deduction could lead to.

And yet this same man, who accepted that birds could hatch from barnacles and that rye could suddenly turn into cornflowers, also produced brilliantly pertinent reports of plants, some of which had never been described before. Writing of the strange, parasitic plant broomrape, he observes that it has ‘a little stalke, somethynge red, aboute twoo spannes longe, sometyme more, rough, tendre, without leves: the floure is somewhat whyte, turnynge towarde yellow … I have marked my selfe, that thys herbe groweth muche aboute the rootes of broome, whyche it claspeth aboute wyth certayne lytle rootes on every syde, lyke a dogge holdying a bone in his mouth: notwythstandying I have not seen any broome choked wyth thys herbe: how be it I have seen the herbe called the thre leved grass or claver utterly strangled, al the naturall juice clene drawen oute by thys herbe.’6 A twentieth-century field guide can scarcely do better: ‘Common broomrape Orobanche minor neither seeds nor has any green colouring as it obtains its nourishment by parasitising the roots of other plants; it gets its name from a large but now uncommon species that thus “rapes” Broom. Common broomrape may be purplish, reddish or yellowish and parasitises pea flowers or composites; it flowers June-September in grassy places.’7

Turner had hoped that his return to England would mark the beginning of a more settled life, with plenty of time to devote to his major work, the Herball (see plate 103). As the 1548 Names had built on the 1538 Libellus, so the Herball would build on the work that Turner had already gathered in Names. He accepted the position of physician in the household of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, and took a house that belonged to the Duke at Kew. From here he made forays into the country, noting the camomile that grew ‘viii myle above London in the wylde felde, in Rychmonde grene, in Brantfurde grene and in mooste plenty of al, in Hunsley [Hounslow] hethe’. But his new position kept him busier than he wished. ‘For these thre yeares and a halfe,’ he complains, ‘I have had no more lyberty but bare iii wekes to bestow upon the sekyng of herbes, and markyng in what places they do grow.’ Those three weeks were spent in the West Country, ‘which I never sawe yet in al my lyfe, which countrey of al places of England, as I heare say, is moste richely replenished wyth al kindes of straunge and wonderfull workes & giftes of nature’. Many plants grew there that were not to be found anywhere else in Britain. On the Isle of Purbeck in Dorset, he mentions seeing the wild gladdon, ‘a litle flour delice growing wylde’. The murky purple iris grows there still, in damp places along the hedges. He also noted a little periwinkle growing wild in the West Country and attempted the notoriously difficult task of distinguishing between the many kinds of fern that flourished there. Blechnum, the hard fern, he had seen ‘oft both in Germany and in diverse places of Somerset shyre and Dorset shyre. It is muche longer than ceterach and the gappes that go between the teth, if a man may call them so, are much wyder then the cuttes that are in ceterach. And the teth are much longer and sharper’. He saw paeonies - ‘the farest that ever I saw was in Newberri in a rych clothier’s garden’ - and talks too of ‘Middow Saffron’ round about Bath and, close to Chard, of finding the little orchid called autumn lady’s tresses.

Anxiously, Turner tried to get the preferment in the Church of England that he felt he now deserved. In June 1549, he writes to Robert Cecil, thanking him ‘for your paynes tayken about ye obteyning of my lycence’. His children, he says, ‘have bene fed so long with hope that they ar very leane. I wold fayne have them fatter if it were possible.’8 That begging letter produced the prebendary of Botevant, near York, but it was not enough and in November 1550, Turner was writing again to Cecil asking for permission to ‘go into Germany & cary ij [iv] litle horsis wth me, to dwell there for a tyme, whereas i may with small coste drynk only rhenishe wyne, & so thereby be delyvered of ye stone [his gallstones], as i was ye last tyme that i dwelt in germany if that i myght have my pore prebende cumyng to me yearly i will for it correct ye hold newe testament in englishe, and wryt a booke of ye causis of my correction & changing of the translation. I will also finishe my great herball & my bookes of fishes, stones & metalles, if god sende me lyfe and helthe.’9

Plate 103: The title page of the first part of A new herball by William Turner, printed by Steven Mierdman in London in 1551

Instead, Turner was awarded the deanery of Wells, though he had to go to court to get John Goodman, the previous incumbent, evicted. ‘I am dene here in wellis,’ he protested, ‘but i can nether get house nor one foot of land … where i shuld have a dosen closes and medowes for my horses i can not get one."10 It’s not the dispensation he cares about so much as a ‘resting place for me and my pore chylder’; there were now three of these ‘chylder’: Peter, Winifred and Elizabeth. A year later, in May 1551, he was still ‘pened up in a chamber of my lorde of bathes with all my hoholde servantes and children as shepe in a pyndfolde … i can not go to my booke for ye crying of childer & noyse that is made in my chamber."11

Despite the noise, the children, the lack of anywhere to lay his books, Turner managed in 1551 to deliver the first part of his Herball (Absinthium-Faba) to his London printer, Steven Mierdman. Mierdman was a Fleming and, like Turner, a deeply committed Protestant; he had come to England from Antwerp to escape prosecution for printing heretical books. He must have had links with Fuchs’s printer, for Turner’s book was illustrated with 169 woodcuts, most of them lifted from Fuchs’s De historia stirpium, which had come out five years previously. This time Turner wrote, not in Latin, as most of his contemporaries did, but in English. Some, he said in his Dedication ‘will thinke it unwisely done, and agaynst the honor of my art that I professe, and agaynst the common profit, to set out so muche knowledge of Physick in Englyshe, for now (say they) every man … nay every old wyfe will presume not without the mordre of many, to practise Physick.’ But, he asks in reply how many, physicians and apothecaries could read Pliny in the original? Dioscorides, after all, wrote in Greek for a Greek-speaking public. ‘If they gave no occasion of murther, then gyve I none.’ In Names he had arranged plants in alphabetical order, using the Latin name, Arthemisia, Arum, as the heading above each description. In the Herball the Latin headings are replaced by English names - mugwort, cuckoo pint (see plate 104) - and where Turner does not know an English common name, he provides one. These are often direct translations of the Latin names, so he gives us goat’s beard from the Latin ‘barba hirci’, which ‘groweth in the fieldes aboute London plentuously’, and hawkweed from the Latin ‘hieracium’ which ‘groweth in Germany about Colon’. Translation wasn’t as easy an option as it might seem. The most commonly used dictionary of the period was Cooper’s Thesaurus Linguae Romanae &’ Britannicae but it listed masses of English equivalents under each Latin term. Nuance was all. If you did not know the plant, it would be all too easy to reach for an entirely inappropriate English phrase. Where direct translation did not produce a sensible name, as with the Latin ‘acanthium’, Turner chose a tag that described the plant in some way: ‘I have not hearde the name of it [acanthium] in englishe,’ he writes in Names, ‘but I thynke it maye be called in englishe otethistle, because the seeds are lyke unto rough otes, or gum thistle, or cotten thistle, because it is gummy and the leaves have in them a thynge lyke cotten, which appeareth when they are broken.’ By writing in English, Turner hoped to spread his knowledge to the widest possible public. It was also another way of distancing himself from the Roman Church, with its Latin credos and canticles. As he said, a priest who did not preach in English was like a watchman on the walls of Berwick, the border town in the north of England: when a Scots raiding party surged down from the hills, there would be no point in him shouting ‘Veniunt Scotii’; no one would take any notice. But Turner’s aim, so in keeping with his fight for a fairer, more equitable society, did not have the effect that he had hoped. Of the three million people living in Britain at the time, perhaps half a million could read. But anyone who could read, read Latin as easily as they read English. And the fact that Turner’s most important book was written in English meant that it never found an audience on the Continent, where he had gathered so much of his information on plants. Latin was the universal language.

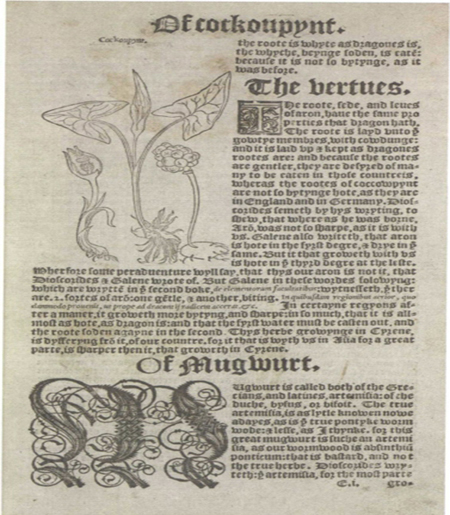

Plate 104: Cuckoo pint (Arum maculatumj and mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) from A new herball by William Turner. The illustration of the arum (reversed here and so most probably pirated) had originally been prepared for Fuchs’s De historia stirpium

He was also unlucky in his timing. Edward VI died before Turner had a chance to settle into his living at Wells and concentrate on part two of his great enterprise. In 1553, after only six years on the throne, Edward was succeeded by his Catholic half-sister Mary, so once again, Turner found himself on the wrong side of the religious divide and had to leave England in a hurry. He went back to Germany, a refuge for many English Protestants, and settled first in Weissenburg, where the local apothecary, Jacob Detter, became another vital contact. Mary’s accession meant that, for a second time, all Turner’s books were banned in England, which diminished still further his chances of finding a wide following. The first ban had been imposed on 8 July 1546 by Henry VIII, who had made it a crime to ‘receive, have, take, or kepe … any maner of booke printed or written’ by Turner and ten other contentious authors.12 Mary reinforced and widened the scope of the ban with a similar proclamation, issued on 13 June 1555, the year in which Ridley and Latimer, Turner’s compatriots at Cambridge, were both burned at the stake. The consequences of disobeying these draconian orders were all too evident, yet an inventory in 1556 of the 302 books belonging to Henry, first Baron of Stafford (1501-63) includes both the Names of 1548 and the Herball of 1551. From the Continent, Turner continued to publish his uncompromising tracts, denouncing the ‘crowish stert uppes’ of the new aristocracy, who enclosed commons and closed down hospitals. Still, he fought for a decent education for all, a decent standard of living for parsons and vicars, and an end to the entrenched practice of selling preferments to the highest bidder.

Turner’s trenchant views kept him out of the country until Mary’s death in 1558. The following year, on 10 September 1559, he preached to a vast and jubilant congregation in St Paul’s, the old church, not yet consumed in London’s great fire. After another protracted court case, he was at last able to evict the tenacious John Goodman and possess his deanery at Wells. Meanwhile, he settled in London and re-established contact with his apothecary friends, John Rich (fl. 1580s-1593) and Hugh Morgan (fl. 1540s—1613). Morgan’s shop and garden were in Coleman Street, which runs north, parallel with Moorgate, from Lothbury up towards London Wall; he knew more about the plants then coming in from the West Indies than anybody else in London. He made a point of keeping in touch with the sea captains whose vessels came into the Port of London. He was also in regular contact with merchants in Venice, where so many novelties first appeared. Morgan’s contacts included fellow apothecaries and pharmacists all over the Continent: Francesco Calzolari and Andrea Bellicocco in Verona; Alberto Martinello and his brother the Syrian doctor Cechino Martinello in Venice; Jacques Raynaudet in Marseilles; Jacques Farges in Montpellier; Valerand Dourez the Fleming in Lille; Wilhelm Driesch and Turner’s friend, Pieter Coudenberg in Antwerp. They exchanged letters, often carried by itinerant booksellers, with news of new discoveries, new names, new treatments, but also sent each other seeds and roots of the plants themselves, the raw material of their trade. It was in Hugh Morgan’s shop that Turner first saw ‘plentye of righte oke miscel [mistletoe]’, which had been ‘sent to hyme oute of Essex’. Spinach was another novelty, ‘an herbe lately found and not long in use’. Turner felt it was a useful addition, though likely to cause stomach ache and wind.

In 1562, the second part of the Herball came out, dedicated to the second Baron Wentworth, ‘whose father with his yearly exhibition did help me, being student in Cambridge of physic and philosophy’. By this time, Turner had already been back in England for four years, but his work was published not in London but in Cologne. His publisher Mierdman, had, like Turner, been forced to leave England when Mary came to the throne but he had not returned. Here was another piece of bad luck. For reasons completely beyond his control, the printer of the first part of the Herball was not able to continue with the rest of it and Turner had no way of knowing when (or even whether) he would be able to come back to England. After being in Weissenburg, Turner had spent the latter part of his second exile based in Cologne, and this is presumably where he had become acquainted with Arnold Birckman who finally published the second part. Birckman, like Mierdman, had access to the illustrations from Fuchs’s book, so Turner could continue to use them (see plate 105). But publishing in Germany a book written in English severely compromised its chances of success: few on the Continent could read it; few in England could get hold of it. Undaunted, Turner pressed on with the great work, conscious, as all who tried to produce these encyclopaedic works were, that he could scarcely keep up with the vast amounts of new plants arriving in Europe.

Outspoken as always, defiant of ecclesiastical control, Turner also continued to preach in his old uncompromising way. Bishop Berkely complained in a letter (1563) to William Cecil and Archbishop Parker at Canterbury that he was ‘much encom-bred with Mr Doctor Turner, Deane of Welles, for his indiscrete behaviour in the pulpitt: where he medleth with all matters and unsemelie speaketh of all estates, more than is standinge with discressyon. He contendeth utterly all Bishops and calleth them White Coats, tippet gentlemen, with other words of reproach much more unsemelie and asketh, who gave them authority, more over me than I over them."13 The Marprelate Tracts, published in the 1580s by the Puritan underground press, tell how, when the Bishop came to dinner, Turner called up his well trained dog: ‘the dog flies at the Bishop and takes off his corner cap - he thought belike it had been cheesecake - and so away goes the dog with it to his master.’14 Despite efforts to get rid of him, Turner hung on to his deanery, and the third and final part of his Herball is dated from Wells, 24 June 1564, four years before his death in London. It was printed, like the previous instalment, by Birckman in Cologne and included many novelties such as nutmeg, ‘from an Ilande of Inde called Badon’, and cassia, which came from ‘the Weste newe found Ilandes, out of Hispaniola’. Hugh Morgan would have kept him informed of the new and unfamiliar things arriving by ship in the Port of London: caraway, cucumber, fenugreek and hemp were among the strange seeds unloaded from the Cock which arrived in London via Bruges on 29 April 1568; the cargoes of the time also included exotic goods such as oranges, lemons, almonds, nutmeg and aniseed.15 Plants that had been dealt with very briefly in the earlier Names received longer (though not necessarily kinder) treatment in the Herball. Speaking, for instance, of the poisonous oleander, Turner had written in Names that ‘I never sawe it but in Italy.’ In the Herball he is more elaborate: ‘I have sene thys tre in diverse places of Italy but I care not if it never com into England, seying it in all poyntes is lyke a Pharesey, that is beuteus without, and within, a ravenus wolf and murderer.’ On dead nettle, he had been brief in Names, giving synonyms, habitat and little else. In the Herball he provides a vivid description: ‘Lamium hath leaves like unto a Nettel, but lesse indented about, and whyter. The downy thynges that are in it like pryckes, byte not, ye stalk is foursquare, the floures are whyte, and have a stronge savor, and are very like unto litle coules, or hoodes that stand over bare heades. The sede is blak and groweth about the stalk, certayn places goyng betwene, as we se in horehound.’ Though he still describes them in terms of the four ‘humours’ - choleric (hot and dry), melancholic (cold and dry), phlegmatic (cold and moist), sanguine (hot and moist), he includes more uses for the plants he mentions, even if he disapproves of them: some women ‘springkle the floures of Cowislip in whyte wine, and after still it and washe their faces with that water to drive wrinkles away, and to make them fayre in the eyes of the worlde rather than in the eyes of God, whom they are not afrayd to offende with the scluttishnes, filthines and foulnes of the soule.’16 Honeysuckle would cure hiccups, but had to be used sparingly for it could induce impotence. Nutmeg was a useful aphrodisiac ‘for cold husbands that would fain have children’. Water lily was the suitable corrective to prescribe for ‘wiveles gentlemen or husban-dles gentleweomen agaynst the unclene dremyng of venery and filthy polutiones that they have on the nyght. For if it be dronken continually for a certayn tyme it weykeneth much the sede.’17

Plate 105: Anagyris (Anagyris foetida) ‘groweth not in Englande that I wote of / but I have sene it in ltalye’ wrote William Turner in the final edition of A new herball, printed by Arnold Birckman in Cologne (1568)

The Herball also provided, for the first time, recognisable descriptions of 238 British native plants.18 Both Turner’s religion and his science depended on interpreting words with forensic accuracy. Like Dioscorides, he was extremely good at linking plants with their natural habitats: he noticed, for instance, how water lilies favoured ‘standyng waters’, that wood sorrel was most often to be found ‘in woddes aboute tree rootes and amonge busshes’, that absinthium or worm-wood ‘groweth commonly in diches whereinto the sake water useth at certeyne tymes to come’ and that the yellow-horned poppy was most likely to be seen in ‘places by the sea syde’. By writing in English Turner had hoped to make his work more easily accessible to an English audience. Mattioli, too, had written in his native tongue, but his book was quickly translated into several other languages and a Latin edition was produced within twenty-one years of the book’s publication. Perhaps, though, Turner felt a kind of patriotic pride in abandoning Latin for the vernacular. Certainly, in the Preface to Names, he had written that he wished to ‘declare to the greate honoure of our countre what numbre of sovereine & strang herbes were in Englande that were not in other nations’. Perhaps he was articulating a desire to make the English language a medium fit for scientific discourse. Perhaps he felt that if enough important books were published in English, scholars in other countries would have no option but to learn the language. It happened in the end. But, like the brilliant Cesalpino, though for different reasons, Turner was ahead of his time. Cesalpino was unread because he was so far ahead of his contemporaries in the thinking that underpinned the divisions of his De plantis. Turner was unread because he was unlucky in his timing. Produced in a foreign country in a foreign tongue, his books were never translated. The title Herball became associated not with him but with a man of much less intellect, probity or vision, the slippery John Gerard. Throughout his life he worked in difficult circumstances. Even in the Preface to the final part of his Herball he complains that ‘beyng so much vexed in the sickness and occupyed with preaching and the study of Divinity and exercise of discipline, I have had but small leasure to write Herballes’.

No portrait of Turner exists, no plant was named after him, as they were for both Fuchs and Mattioli. But after his death in July 1568, his widow, Jane, the daughter of a Cambridge alderman, put up a memorial to him in his parish church, St Olave’s, Hart Street, in the City of London. On a hot summer’s day, 436 years later, I make my way through the crowds of commuters spilling out of Fenchurch Street station, with a small bunch of West Country flowers for Turner. Sadly it does not include the thorow-wax he had admired in fields between Somerton and Martock in Somerset; once widespread in the arable land of the West Country, it is now extinct in the wild. Turner’s church, just along the street from his house at Crutched Friars, was founded in the eleventh century. The present building, which dates from 1450, is the third one on the site and was badly damaged in the Blitz of April 1941. Miraculously, the memorials inside survived and a board by the church entrance notes the most significant of them: Sir James Deane (1608) merchant adventurer, Samuel Pepys (1669) diarist, Sir Andrew Riccard (1672) chairman of the East India Company … There is no mention of William Turner. Inside, Pepys and Riccard face each other across the chancel of the superb small church, both extravagantly commemorated in stone. On the south wall is the brightly painted bust of Peter Capponi, an exiled Florentine ‘of ancient lineage’, who died of the plague in 1582. Unexpectedly, someone is playing a Schubert sonata. Tiptoeing round the grand piano set in front of the altar, I finally find Turner, completely overshadowed by Deane, the merchant adventurer, who has a huge showy memorial. As befits a man who railed against the extravagant vestments of sixteenth-century clerics and taught his dog to snatch the caps from the heads of visiting bishops, Turner’s memorial is a very plain, small rectangle of creamy marble, bordered in black, like a Victorian mourning card. In densely lettered Latin, the inscription stresses Turner’s piety, and marks how he ‘fought against the enemies of the Church and the Commonwealth, chiefly the Roman Antichrist’. There is no mention of his Names or his Herball, the first original works on plants ever written by an Englishman.

Unlucky Turner. Too soon after he finally found himself in the right place at the right time, he died. And, like so many pioneers, he died before the worth of what he was doing was recognised. His patient synthesising of plant names - Greek, Latin, English, French, German, Italian - banished much of the confusion that was bound to exist when common names were the only common currency. By way of his extensive travels, he set England on the intellectual map of Europe. The intellectual isolation that had marked the few English plantsmen of the first half of the sixteenth century had completely vanished by the second half. After Turner’s death, England became a magnet for anyone interested in the study of plants. In 1540, Turner had fled to the Continent to escape Catholic persecution. Thirty years later, and for the same reason, the Flemish scholar, Matthias de l’Obel (Lobelius) came in the opposite direction and, in terms of plantsmanship, found a country very different from the one Turner had been forced to leave. Turner laid the foundation for the preeminence of this later generation of English plantsmen: John Goodyer, John Parkinson, John Ray. He was the vital link between the early scholar-botanists and the later generation of more practical, experimental gardeners, many of whom were based in London. But as is the way with foundations, Turner’s were, all too soon, buried and forgotten. His name ought to be on that board at St Olave’s.