XIX

NEW PASTURES

1550—1580

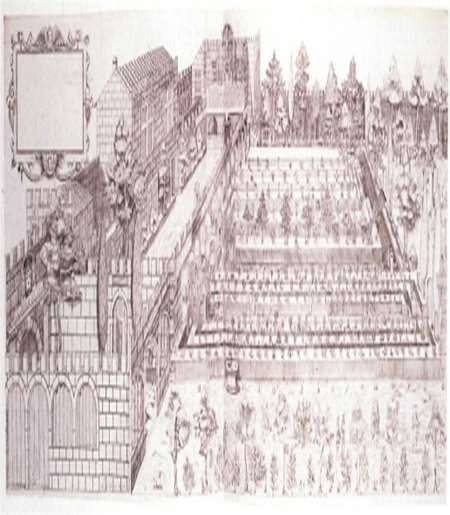

GESNER’S DEATH IN 1565, followed the next year by those of Rondelet and Fuchs, brought to an end a particular phase of research into res herbaria. In the first half of the sixteenth century, four great sets of plant illustrations had been accumulated, circulated, annotated, compared. Four important botanic gardens had been established in Italy, providing a model for those that followed later in the rest of Europe: Leipzig had one by 1580, Leiden in 1587, Basel by 1588, Heidelberg by 1593, Montpellier in 1597. Thomas Platter, Felix’s younger brother, who studied medicine at Montpellier between 1595 and 1599, described how the new garden (see plate 114) had been created there by Rondelet’s successor, Pierre Richer de Belleval,

between the gates of the Peyrou and Saint-Gely, a gunshot away from the walls of the town. He has had a large well or cistern dug there, beside which have been built several grottoes that are deliciously cool in summer; here aquatic plants are cultivated in humid and mossy earths brought here by his order. Everything is perfectly managed for other species too; he has even built a mound for them, with several high terraces one above the other. Each part of the garden has its own entrance … If the King does not reimburse him for all his expenditure, he must be a ruined man.1

In the summer of 1596, Thomas Platter and his friends went hunting for plants on Jardin des Plantes (1854) the shoreline at Montpellier, as his brother had done forty years before, but the monastery in the woods at Grammont was now in ruins, and the little church had become a farmhouse. As a young student in the 1550s, Felix Platter had witnessed at first hand the massacres that followed the persecution of French Protestants; the religious wars in the Languedoc persisted almost to the end of the century. By the time of Gesner’s death, the first religious refugees from Flanders had already settled in England; by 1562, a Huguenot colony was trying to establish itself in Florida. The Montpellier garden, so carefully planned and planted by Richer de Belleval lasted scarcely thirty years, for Louis XIII did not share Henri IV’s tolerance towards the Montpellier Protestants. In the winter of 1621-2 his army laid siege to the town. The soldiers made their camp in the botanic garden and left it ‘entierement desmoly et mis en ruyne’. The irony was that Rondelet had been a Protestant who never lost his Catholic friends; Richer de Belleval was a Catholic who saw his life’s work destroyed by a Catholic army.

Plate 114: The botanic garden at the University of Montpellier as it looked in 1596. From Charles Martin’s

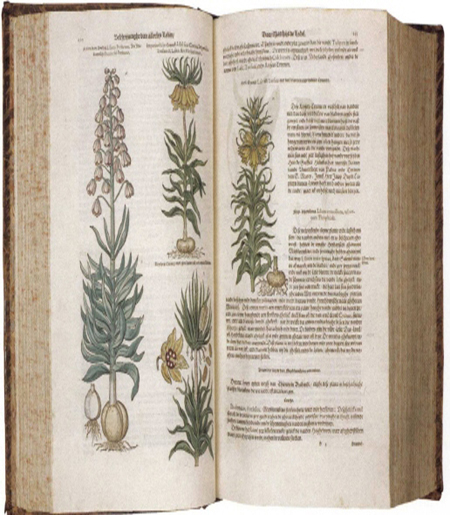

In an intellectual sense, the Counter-Reformation had closed Italy in on itself. Gradually France, Germany and the Low Countries took the lead in producing scholars with the ability to take forward the pioneering work that, from the early Renaissance onwards, had been focused in Italy. The Reformation encouraged Protestants to rediscover a delight in ‘the works of the Lord’, to reaffirm a symbiosis with the natural world. By the middle of the sixteenth century the shift was almost complete. Italy still produced great plantsmen but the names that dominate the field in the latter part of the sixteenth century are all from the Low Countries: Rembert Dodoens (1517-1585) born in Mechlin, Belgium, Charles de l’Ecluse (1526-1609) born at Arras, and Matthias de l’Obel (1538-1616) born at Lille, both then in Flanders. Together they produced an avalanche of plant books, most of them published in Antwerp by the Flemish printer Christophe Plantin (c. 1520-1589) who commissioned another important set of illustrations, the fifth to be produced between 1530 and 1590. No woodblocks have ever worked harder than Plantin’s, recycled in a whole series of volumes which culminated in the compendium of 2,173 illustrations that appeared in the Icones stirpium seu plantarum tarn exoti-carum of 1591.

The new botanic gardens helped create a taste for the rare and the strange; rich men now laid out gardens which were intended purely for pleasure and filled them with the exotic fritillaries, tulips, narcissi and lilies that had begun to appear in Europe from Constantinople. The catalyst in this instance was the Fleming, Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq (1522-1592), the traveller, linguist, scholar and antiquarian who from 1554 to 1562 was Emperor Ferdinand’s ambassador at Constantinople, the centre of the Ottoman Empire. In a series of letters addressed to his friend Nicholas Michault,2 Busbecq, a keen plantsman, describes the country he and his entourage passed through on their way to the Ottoman court:

We stayed one day in Adrianople and then set out on the last stage of our journey to Constantinople, which was now close at hand. As we passed through the district we everywhere came across quantities of flowers - narcissi, hyacinths and tulipans as the Turks call them. We were surprised to find them flowering in mid-winter, scarcely a favourable season. There is an abundance of narcissi and hyacinths in Greece, and they possess so wonderful a scent that a large quantity of them causes a headache in those who are unaccustomed to such an odour.3

The Anglo-French jeweller Sir John Chardin, who travelled in the Near East in the 1660s, left a similar account of the rich flowers he saw, so desirable to Western eyes:

By the vivacity of their colours [these flowers] are generally handsomer than those in Europe, and those of India … Along the Caspian coast there are whole forests of orange trees, single and double jasmine, all European flowers, and other species besides. Towards Media and the southern parts of Arabia, the fields produce of themselves tulips, anemones, single ranunculus, of the finest red, and imperial crowns. In other places, as round about Isfahan, the jonquils grow of themselves … they have in the proper season seven or eight sorts of daffodils, and there are flowers blooming all winter long … white and blue hyacinths … dainty tulips and myrrh … in spring, yellow and red stock and amber seed of all colours and a most unusual flower called the clove pink, each plant bearing some thirty blooms.

Chardin also noted

the lily of the valley, the lily and violets of all colours, pinks and Spanish jasmine of a beauty and perfume surpassing anything found in Europe … There are beautiful marshmallows and, at Isfahan, charming short-stemmed tulips … The rose which is so common among them is of five sorts of colours besides its natural one, white, yellow, red and others of two colours viz red on one side and white or yellow on the other … I have seen a rose tree which bore upon one and the same branch roses of three colours, some yellow, some yellow and white, and others yellow and red.4

Merchants soon discovered that the plants that grew from bulbs and corms - crocus, cyclamen, fritillaries, hyacinths (see plate 115), lilies, tulips - were not difficult to transport from East to West because they died down soon after they had flowered and remained dormant until the following growing season. And avid collectors in the West also discovered that these treasures were not too difficult to grow, if you kept mice away from the bulbs and dried them off in summer. The rarity value of novelties such as the crown imperial and the prices paid for them obliged gardeners to watch their new acquisitions closely and try, instinctively, to guess what they most needed to survive in a climate that was damper, cooler, less extreme in its heats and chills than their natural habitats.

Ptate 115: Hyacinths, both single and double from Emmanuel Sweert’s Florilegium (1612)

The arrivals, these infidel flowers, the first great wave of foreign plants to arrive in Western Europe, were shocking in their glamour, their outrageous colours, their charisma and allure. Until the 1560s, most flowers grown in European gardens had been natives of Europe and the Mediterranean: calendulas, different coloured columbines, violas, odd kinds of primrose. But in April 1559, under grey Bavarian skies, a tulip from the East suddenly erupted in brilliant scarlet in the garden of a rich Augsburg silversmith. With equal drama, in the 1570s the first crown imperial (see plate 116) pushed its thick fleshy stem through the bare earth of spring to produce a flower that was disgracefully, flagrantly set to seduce. From the top of its thick stem, it produced orange bells, symmetrically arranged in a perfect circle, thick and fleshy, the central pistil hanging like a clapper inside. ‘In the bottom of each of these bels,’ wrote the English plantsman John Gerard, ‘there is placed sixe drops of most cleare shining sweet water, in taste like sugar, resembling in shew faire orient pearles; the which drops if you take away, there do immediately appeare the like, notwithstanding if they may be suffered to stand still in the floure according to his owne nature, they will never fall away, no not if you strike the plant until it be broken.’5 On top of the bells small green leaves arranged themselves in a topknot, an arrangement quite unlike any other flower that had ever been seen in Europe. The crown imperial was a self-made centrepiece and demanded attention. The soft, fleeting scents of the European spring - primroses, violets - were now overlaid by the heavier, insistent, rocking smell of the hyacinth: musky, almost overpowering in its intensity.

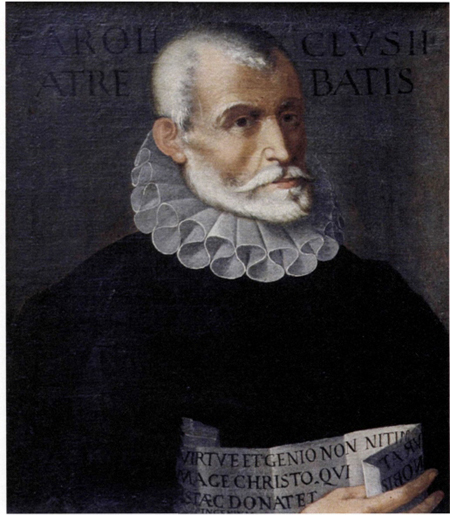

Busbecq, though, was only part of a flourishing export trade which, during the reigns of Sultan Selim I and Sultan Murad I, fostered strong links between Turkey, Austria and the Netherlands. Most new plants coming from that quarter quite quickly found their way to Charles de l’Ecluse (known to his contemporaries as Carolus Clusius), who had a particular interest in bulbs. Clusius (see plate 117) had studied under Rondelet at Montpellier; then, in the same way that Cosimo I de’ Medici had persuaded Luca Ghini to come to Pisa, Maximilian II of the Holy Roman Empire induced Clusius to look after the Imperial Botanic Garden in Vienna. Clusius’s contemporary, Rembert Dodoens, was also summoned, as the emperor’s personal physician. Ferdinand, Maximilian and his successor Rudolf collected rare plants and other oddities with the furious zeal so typical of the age. Coins, medals, manuscripts, fossils, gemstones, skulls, shells, the gran libro della natura, animal, vegetable, mineral, were crammed into cabinets of curiosities, the wunderkammern that became such a feature of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Philip II of Spain, Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol, Duke William V and Duke Maximilian I of Bavaria were all equally infected with this cultura della curiosita. The collections were microcosms of the natural world, its curiosities and treasures, and all over Europe tremendous hoards were built up by private collectors such as Ferrante Imperato in Naples, Ulysse Aldrovandi in Bologna, Canon Manfredo Settala in Milan, Olao Worms in Copenhagen, and the Tradescants in London.

Plate 116: The showy crown imperial (Fritillaria imperialis) introduced into Europe from Constantinople in the second half of the sixteenth century. This illustration was made in the 1630s by Pieter van Kouwenhoorn

At the heart of one of the richest and most powerful courts of the age, Clusius had to ensure that the Imperial Botanic Garden held at least as many rare plants as any other in Europe. The emperor’s ambassadors were primed to send back novelties from the various countries in which they served. In 1576 Clusius received a huge consignment of rare trees and shrubs from David von Ugnad, who had succeeded Busbecq in Constantinople. Unfortunately, most were dead; only a horse chestnut and something that von Ugnad called a Trabison curmasi, the date or plum of Trebizond, had survived the long journey. Travelling was naturally more stressful to large plants than it was to bulbs, perfectly packaged and, in their dormant season, eminently portable. But the surviving horse chestnut and the Trebizond plum both settled like natives in Europe and were quickly spread between enthusiastic gardeners. Those who grew the foreign plants did not always understand that they were used to tougher conditions than they found in their new homes. In 1629, the English plantsman John Parkinson described a Trebizond plum (or cherry laurel as it became known in England) flowering in the Highgate garden of James Cole ‘which hee defended from the bitternesse of the weather in winter by casting a blanket over the toppe thereof every yeare, thereby the better to preserve it’.6

Clusius also travelled widely himself, introducing at least 200 new plants from expeditions in Spain and Portugal. All these were described in his first original work, Rariorum aliquot stirpium per Hispanias observatorum historia, which was published by Christophe Plantin in 1576. The book contained an important Appendix which had nothing to do with Spain, but gave a detailed list of the plants that Clusius had up to that time received ‘ex Thracia’, that is, from the east Balkan peninsula. Plantin had woodblock illustrations cut especially for the book, but in the end they were used in a work of Dodoens’s before Clusius ever got hold of them. Fuchs would have burst several blood vessels over the matter; Clusius merely commented that he and Dodoens were ‘united by friendship of old’, and that ‘whatever friends possess ought to be freely shared’. In 1571, on his first trip to England, Clusius went plant-hunting around Bristol with Lobelius (Matthias de l’Obel). William Turner had posited the West Country as a kind of Mecca for plant-lovers and Clusius tracked down West Country specialities such as colchicum, scurvy grass, tutsan, yellow wort, a rare pimpernel, lady’s mantle and a special kind of pignut. In London, where Lobelius was at that time based, Clusius met the poet Sir Philip Sidney and listened to Francis Drake’s account of his adventures in the New World.

Plate 117: A portrait of Carolus Clusius (Charles de I’Ecluse 1526-1609), a key figure in the web that connected plantsmen of the sixteenth century. The portrait is by Filippo Paladini

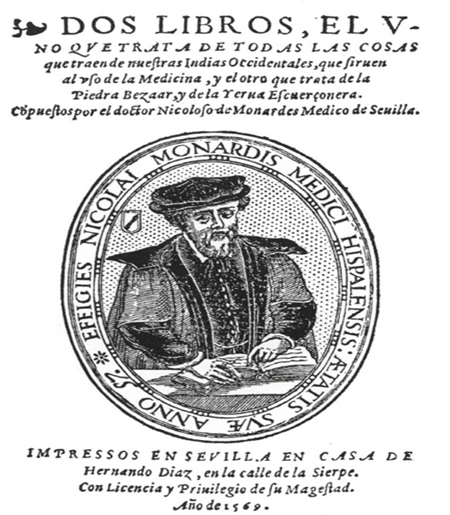

It was in London, too, that Clusius came across a work that had recently been published in Seville by a Spanish physician, Nicolas Monardes (1493-1588), the first book ever to describe the strange and unknown plants of the Americas. Called Dos Libros … (see plate 118), it described the extraordinary things coming into Spain from what were then known as the Occidental Indies, the brave new world that lay west over the Oceano Occidentale. One of Monardes’s sons had settled in Peru and the various forays made by Spanish conquistadores in South America brought dispatches from these previously unchartered territories directly into Cadiz and the cities of southern Spain. ‘And as there is discovered newe regions, newe kyngdomes, and newe Provinces by our Spanyardes,’ wrote Monardes, ‘thei have brought unto us newe Medicines and newe Remedies.’ The plants that came into Western Europe from Constantinople and the Near East had been rated by plantsmen for their beauty and rarity, but the plants that, shortly after, began to flood into Europe from the New World were valued chiefly for their medicinal qualities. The pox had arrived in the Old World with Christopher Columbus and swept through Europe faster than the plague. The drugs extracted from the new South American plants were far stronger and more effective against syphilis than any cure distilled from European ingredients. Intrigued by Dos Libros … and Monardes’s descriptions of plants that few Europeans had ever seen, Clusius translated it into Latin and Plantin published the new edition in 1574. Three years later it was available in English, published under the winning title Joyfull newes out of the newe founde worlde by John Frampton, a merchant who had spent much of his working life in Spain. In Monardes’s book, he promised, readers would find ‘declared the rare and singuler vertues of diverse and sundrie Hearbes, Trees, Oyles, Plants, and Stones, with their applications, as well for Phisicke as Chirugerie, the saied being well applied bryngeth such present remedie for all deseases, as maie seme altogether incredible …’ The book, in its various editions, was an immediate success, entrancing European readers with its descriptions of

that countrie, whiche thei cal the newe Spaine, as in that whiche is called the Peru, where there are many Provinces, many Kingdomes, and many Cities, that hath contrary and divers customes in them, whiche there hath been founde out, thynges that never in these partes, nor in any other partes of the worlde hath been seen, nor unto this daie knowen: and other thynges, which now are brougt unto us in greate aboundance, that is to saie, Golde, Silver, Pearles, Emeraldes, Turkeses, and other fine stones of great value … And besides these greate riches, our Occidentall Indias doeth sende unto us many Trees, Plantes, Herbes, Rootes, Juices, Gummes, Fruites, Licours, Stones that are of greate medicinall vertues … And this is not to bee merveiled at, that it is so, for the philosopher doeth saie that all Contries doeth not give Plantes and Fruites alike: for one Region yeldeth suche Fruites, Trees and Plantes, as another doeth not.7

Plate 118: The title page of Dos Libros in which the Spanish doctor Nicolas Monardes gave some of the first accounts of the plants of the New World. It was printed in Seville in 1569

The close trade links between Spain and England meant that the goods brought out of the New World by Spanish merchants quickly found their way ‘hether into Englande, by suche as dooeth daiely trafficke thether’.

Monardes talked of ‘the Islande of Cuba’, where ‘certine Fountaines at the Seaside … cast from them a kinde of blacke Pitch’ which, mixed with tallow, the Spanish sailors used to tar their ships. He described the resin that the native Indians gathered ‘by waie of Incision, by giving cuttes in the Trees of whiche forthewith the licour doth droppe out’. The resin, ‘called in the Indians’ language, Caranna’, came into Spain by way of Cartagena and Nombre de Dios, and the Spaniards continued to call it by its South American name. The Americas also provided a source of balsam, the aspirin of the Renaissance pharmacy. The drug had previously been imported from Egypt, but as Monardes explained, ‘it is many yeres that it failed, because the Vine from whence it came, dried up’. When balsam initially came into Spain from the Americas it cost a small fortune, ‘one ounce was worthe tenne Duccates and upwardes’. Later, merchants ‘brought so muche and suche great quantity, that it is nowe of small valewe’. But of all the plants that the New World produced the three most important were guaiacum, the bark of a tree that grew round Sancto Domingo; China, a root rather like ginger; and sarsaparilla, ‘a thyng come to our partes after the China. It may be twenty yeres that the use thereof came to this City.’ All were considered extremely effective against syphilis8 ‘except the sicke man doe returne to tumble in the same bosome, where he tooke the firste’.

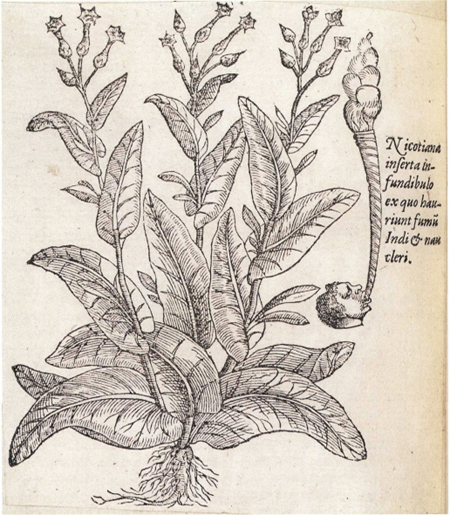

Famously, the Americas also produced the tobacco plant, a picture of which decorates the title page of the second part of Monardes’s book. Though he fills sixteen pages with the ‘greate vertues’ of tobacco, it was a while before the smoking habit caught on in Europe; at first tobacco was used ‘to adornate Gardeines with the fairenes thereof, and to geve a pleasaunt sight’. Monardes explains that among the American Indians the plant is known as ‘peciels’ (’tobacco’ came from the Spanish, after the island of the same name) and that they

for their pastyme, doe take the smoke of the Tabaco, for to make theimselves drunke withall, and to see the visions and thinges that doe represent to them, wherein thei dooe delight …

The blacke people that hath gone from these partes to the Indias, hath taken the same maner and use of the Tabaco that the Indians hath, for when thei see theimselves wearie, thei take it at the nose, and mouthe, and it dooeth happen unto theim, as unto our Indians, Hying as though thei were dedde three or fower howers: and after thei doe remaine lightened, without any wearinesse, for to laboure againe: and thei dooe this with so greate pleasure, that although thei bee not wearie, yet thei are very desirous for to dooe it: and the thyng is come to so muche efecte, that their maisters doeth chasten theim for it, and doe burne the Tabaco, because thei should not use it, whereupon thei goe to the desartes, and secrete places to dooe it, because thei maie not bee permitted, to drinke themselves drunke with Wine …

When thei use to travaile by waies, where thei finde no water nor meate: Thei take a little baule of these, and thei put it between the lower lippe and the teethe, and thei goe chewyng it all the tyme that thei doe travell, and that whiche thei doe chewe, thei doe swallowe it doune, and in this sorte thei dooe journey three or fower daies, without havyng neede of meate, or drinke.9

Frampton, in his translation of Monardes’s work, added that the herb was known among the French as ‘nicotiane’ and explained how ‘Maister Jhon Nicot, Counseller to the Kyng, beeyng Embassadour for the Kyng in Portugall, in the yere of our Lorde 1559, went one daie to see the Prysons of the kyng of Portugall and a gentleman beeyng the Keeper of the saied Prions presented hym this hearbe, as a strange Plant brought from Florida. The same Maister Nicot caused the saide hearbe to be set in his Garden …’ Already by 1570, Lobelius was writing about tobacco in his Stirpium adversaria nova, undecided whether to call it by its French name (Nicotiana gallorum) or its Spanish one (’Sana sancta Indorum’). He shows a picture of the plant (see plate 119) very similar to the one that Monardes had used, but sets alongside it a bizarre vignette of a vast horn-like cornucopia issuing from the mouth of an American Indian, with an alarming amount of smoke and flames coming out of the top of it. It was scarcely surprising then, that smoking, as a ‘pastyme’, was not an immediate attraction in Europe.

Monardes also writes of coca, ‘that hearbe so celebrated of the Indians’, which was used as a kind of currency to buy ‘Mantelles, and Cattell, and Sake, and other thinges whiche doe runne like to money amongest us’. The coca seed was sown, he explained ‘as we doe put here a Garden of Beanes, or of Peason’ in carefully tilled earth. The use of coca among the Indians was ‘a thing generall’, and Monardes describes the Indians’ method of preparing the drug:

Plate 119: The tobacco plant (Nicotiana tabacum) as it appeared in Lobelius’s Stirpium adversaria nova (1570). The illustrator has taken a fanciful view of the way that tobacco was smoked by the ‘Indians’ of South America

Thei take Cokles in the shelles, and they doe burne them and grinde them, and after they are burned they remaine like Lyme, verie small grounde, and they take of the Leves of the Coca, and they chawe them in their Mouthes, and as they goe chawing, they goe mingling with it of that powder made of the shelles in suche sorte, that they make it like to a Paste, taking lesse of the Powder than of the Hearbe, and of this Paste they make certane small Bawles rounde, and they put them to drie, and when they will use of them, they take a little Ball in their mouthe, and they chawe hym … and so they goe, using of it al the tyme what they have neede, whiche is when they travaill by the waie, and especially if it be by waies where there is no meate or lacke of water. For the use of their little Bawles dooe take the hunger and thurste from them, and they say that they dooe receive substaunce, as though that they did eate. When thei will make themselves dronke and bee out of judgemente, thei mingle with the Coca the leaves of the Tabaco, and thei doe chewe them all together, and thei go as thei were out of their wittes, like as if thei were dronke whiche is a thyng that dooeth geve them greate contentment to bee in that sorte.10

Unlike tobacco, coca didn’t find its way into Lobelius’s book, nor in any other of the wordy torrents published in the second half of the sixteenth century. The coca leaves came from a semi-tropical South American shrub, Erythroxylon coca that could never grow in the European climate. Like cinnamon and cloves, it remained fixed in the European mind as an ingredient rather than a living plant.

But European gardeners very quickly took to the ‘Hearbe of the Sunne’ that Monardes described (see plate 120) and which he said had been grown in Spanish gardens for some years past. ‘It casteth out the greatest flowers, and the moste pertic-ulars that ever hath been seen,’ he wrote. ‘It is greater then a greate Platter or Dishe, the whiche hath divers couleurs. It is needfull that it leane to some thyng, where it groweth, or ellese it will bee alwaies falling: the seede of it is like to the seedes of a Melon, sumwhat greater, his flower doth tourne itselfse continously towardes the Sunne, and for this they call it of his name, the whiche many other flowers and hearbes do the like, it showeth marveilous faire in Gardines."11 Gerard was equally enthusiastic, especially about the centre of the sunflower, ‘made as it were of unshorn velvet, or some curious cloath wrought with the needle’. When the plant was mature, the seed appeared ‘set as though a cunning workman had of purpose placed them in very good order, much like the honycombs of Bees’. The seeds, though, were so numerous (sometimes more than 2,000 in a single head) and the plant itself so easy-going in its habits, that later in the seventeenth century the sunflower became a common flower and so fell out of favour in smart gardens. ‘Not at all respected’ said John Rea, dismissively in 1665. But in 1606, Johann Conrad von Gemmingen, the Prince-Bishop of Eichstatt, had been proud to include it in the fabulous collection of flowers he grew in his garden at Eichstatt, south of Nuremberg. Under the name of ‘Flos solis major’ it blazes on the page of the Hortus Eystettensis, an illustrated record of the Prince-Bishop’s garden with 367 plates illustrating more than a thousand of the plants in his collection.

Plate 120: The sunflower (Helianthus annuusj which created a sensation when it was first brought into Europe from South America. The illustration comes from Rembert Dodoens’s Florum et coronarium, printed in Antwerp in 1568

The sunflower, sacred to the Aztecs, carved as an emblem on Inca temples, had its own long-established indigenous name, as did tobacco. Those names may have travelled back with the plants when they were first brought to Europe. But they were not adopted, or even adapted for European use, though the tags hung on them sometimes acknowledged their origin. The sunflower, which Frampton in 1577 had translated from Monardes as ‘the herbe of the sunne’, had already appeared in the second edition of Rembert Dodoens’s book Florum et coronarium (1569) under the label ‘Chrysanthemum Peruvianum’. Dodoens writes that the plant, still then rare, had already flowered in the gardens of the Royal Palace in Madrid and also in the botanical garden at Padua. Philip Brancion, an avid amateur grower, had not been so successful in the cooler climate of Malines. His plant had been cut down by frost before it ever reached flowering size. But in an amazingly short time after its introduction, the sunflower had already collected a whole bagful of epithets. Lobelius uses three different names in his Plantarum of 1576: ‘Solis flos Peruvianus’, ‘Sol Indianus’ as well as Dodoens’s ‘Chrysanthemum Peruvianum’. All these alternative names were gradually sorted and sifted, abandoned and taken up again until it was finally settled that the sunflower should be christened Helianthus, because it followed the sun.

In Europe, only the Spaniards sometimes continued to use the original names for the plants they brought in from the New World. Though brutal colonisers, they had unusual respect for the plant knowledge of the indigenous people of Mexico. The vast manuscript, Rerum medicarum Novae Hispaniae thesaurus, presented to Philip II of Spain by the king’s physician, Francisco Hernandez (c.1514-1587), adopts many of the authentic Mexican names for the plants described in the text (they included the first description of the ‘cocoxochitl’ or dahlia). The original names are preserved too in a manuscript (see plate 121) made in 1552 at the Roman Catholic College of Santa Cruz by two Aztec authors: Martin de la Cruz, an ‘Indian physician … who is not theoretically learned, but is taught only by experience’, and Juannes Badianus, who translated the work into Latin. It includes a picture of the showy marvel of Peru which quickly became a favourite in European gardens. Usefully, it also recommends plant extracts guaranteed to cure ‘the fatigue of men working in government departments’.12

Plate 121: Marvel of Peru (Mirabilis jalapa) and other plants from an Aztec manuscript, the Badianus Herbal, made in 1552

Plate 122: Fritillaries (Fritillaria persica and Fritillaria imperialis) from Lobelius’s Kruydtboeck of 1581, printed by Christophe Plantin in Antwerp and hand-coloured in his workshop