t The basilica of Santi Giovanni e Paolo on the Celian Hill

t The basilica of Santi Giovanni e Paolo on the Celian Hill

Santi Giovanni e Paolo is dedicated to two martyred Roman officers whose house originally stood on this site. Giovanni (John) and Paolo (Paul) had served the first Christian emperor, Constantine. When they were later called to arms by the pagan emperor Julian the Apostate, they refused and were beheaded and buried in secret in their own house in AD 362.

Built towards the end of the 4th century, the church retains many elements of its original structure. The Ionic portico dates from the 12th century, and the apse and bell tower were added by Nicholas Breakspeare, the only English pope, who reigned as Adrian IV (1154–9). The base of the impressive 13th-century Romanesque bell tower was part of the Temple of Claudius that stood on this site. The interior, which was remodelled in 1718, has granite piers and columns. A tomb slab in the nave marks the burial place of the martyrs, whose relics are preserved in an urn under the high altar. In a tiny room near the altar, a magnificent 13th-century fresco depicts the figure of Christ flanked by his Apostles (to see it, ask the sacristan who will be able to unlock the door). Excavations carried out beneath the church have revealed two 2nd- and 3rd-century Roman houses, the Case Romane del Celio, that were used as a Christian burial place. Well worth a visit, the Roman houses, which include 20 rooms and a labyrinth of corridors, have beautifully restored pagan and Christian frescoes. The walls are painted to resemble precious marble.The arches that are found to the left of the church were originally part of a 3rd-century street of shops.

⌂ Clivo di Scauro # 10am–1pm & 3–6pm Thu–Mon ∑ caseromane.it

Historically, this church has links with England, for it was from here that St Augustine was sent on his mission to convert England to Christianity. The church was founded in AD 575 by San Gregorio Magno (St Gregory the Great), who turned his family home on this site into a monastery. It was rebuilt in medieval times and restored in 1629–33 by Giovanni Battista Soria. The church is reached via steps from the street.

The forecourt contains some interesting tombs. To the left is that of Sir Edward Carne, who came to Rome several times between 1529 and 1533 as King Henry VIII’s envoy to gain the pope’s consent to the annulment of Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon.

The interior, remodelled by Francesco Ferrari in the mid-18th century, is Baroque, apart from the fine mosaic floor and some ancient columns. At the end of the right aisle is the chapel of St Gregory. Leading off it, another small chapel, believed to have been the saint’s own cell, houses his episcopal throne – a Roman chair of sculpted marble. The Salviati Chapel, on the left, contains a picture of the Virgin said to have spoken to St Gregory.

Outside, amid the cypresses to the left of the church, stand three small chapels, dedicated to St Andrew, St Barbara and St Sylvia (Gregory the Great’s mother). The chapels contain frescoes by Domenichino and Guido Reni.

In summer Villa Celimontana hosts an excellent jazz festival.

The arch was built in AD 10 by consuls Caius Junius Silanus and Cornelius Dolabella, possibly on the site of one of the old Servian Wall’s gateways. It was made of travertine blocks and later used to support Nero’s extension of the Claudian aqueduct, built to supply the Imperial Palace on the Palatine Hill.

The church overlooks the Piazza della Navicella (little boat) and takes its name from the 16th-century fountain. Dating from the 7th century, the church was probably built on the site of an ancient Roman firemen’s barracks, which later became a meeting place for Christians. In the 16th century Pope Leo X added the portico and the coffered ceiling.

In the apse behind the modern altar is a superb 9th- century mosaic commissioned by Pope Paschal I. Wearing the square halo of the living, the pope appears at the feet of the Virgin and Child. The Virgin, surrounded by a throng of angels, holds a handkerchief like a fashionable lady at a Byzantine court.

The Dukes of Mattei bought this land in 1553 and transformed the vineyards that covered the hillside into a formal garden. As well as palms and other exotic trees, the garden has its own Egyptian obelisk. Villa Mattei, built in the 1580s and now known as Villa Celimontana, houses the Italian Geographical Society.

The Mattei family used to open the park to the public on the day of the Visit of the Seven Churches, an annual event instituted by San Filippo Neri in 1552. Starting from the Chiesa Nuova, Romans went on foot to the city’s seven major churches and, on reaching Villa Mattei, were given bread, wine, salami, cheese, an egg and two apples. The pine-shaded park, now owned by the city of Rome, makes an ideal place for a picnic and has a playground with swings.

t The Egyptian obelisk in the grounds of Villa Celimontana

This small church is of great historical interest, as it was granted to St Dominic in 1219 by Pope Honorius III. The founder of the Dominican order soon moved his own headquarters to Santa Sabina, San Sisto becoming the first home of the order of Dominican nuns, who still occupy the monastery. The church, with its 13th-century bell tower and frescoes, is also a popular place for weddings.

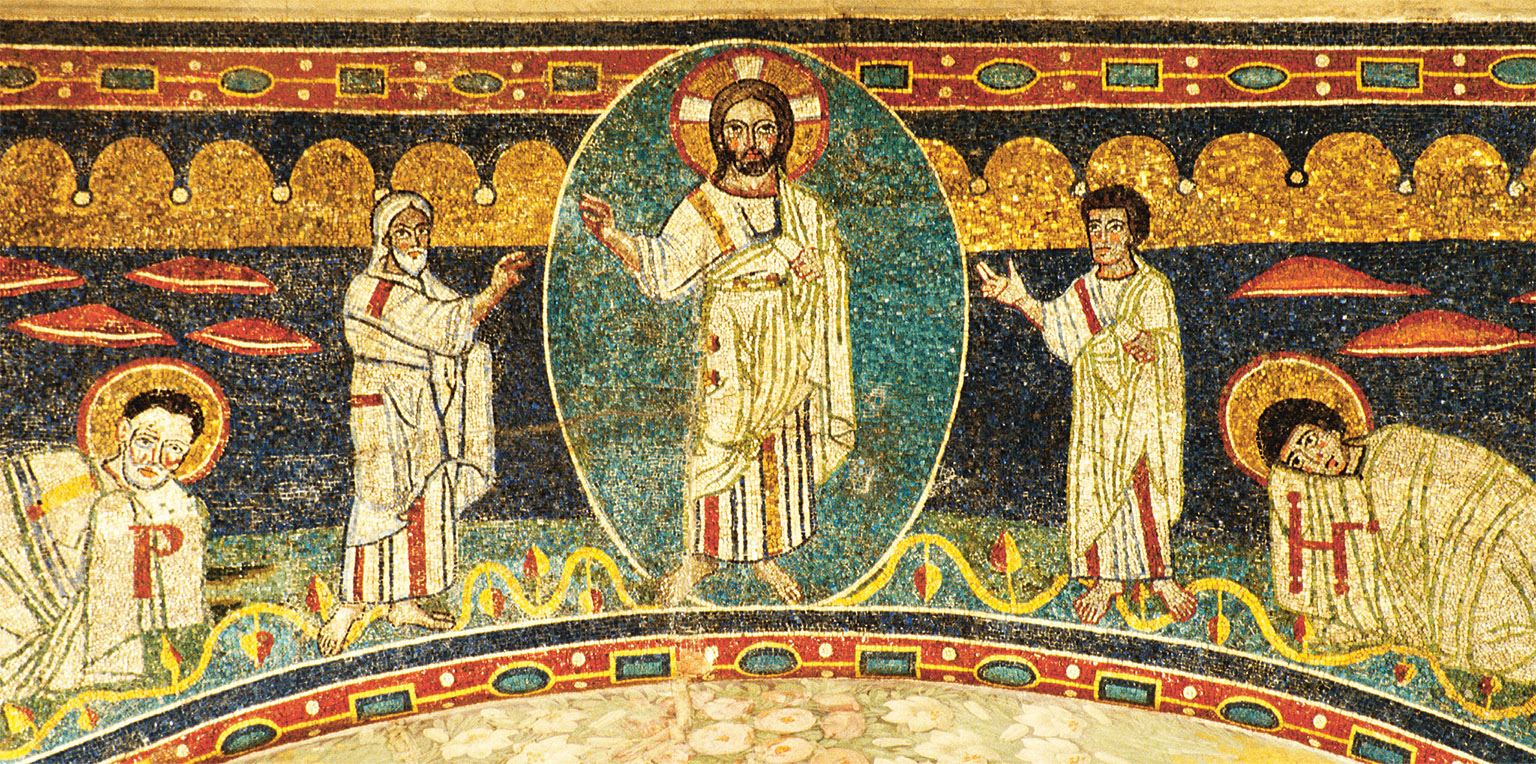

t Detail of a 9th-century mosaic in the church of Santi Nereo e Achilleo

According to legend, St Peter, after escaping from prison, was fleeing the city when he lost a bandage from his wounds. The original church was founded here in the 4th century on the spot where the bandage fell, but it was later re-dedicated to the 1st-century AD martyrs St Nereus and St Achilleus. Restored at the end of the 16th century, the church has retained many medieval features, including several fine 9th-century mosaics on the triumphal arch. A magnificent pulpit rests on an enormous porphyry pedestal which was found nearby in the Baths of Caracalla. The walls of the side aisles are decorated with grisly 16th-century frescoes by Niccolò Pomarancio, showing in clinical detail how each of the Apostles was martyred.

This splendid old church was built over Roman ruins of the 2nd century AD. The lovely Renaissance façade was designed by Giacomo della Porta. The fine Cosmatesque mosaic work and carving inside rival that of any church in Rome. The episcopal throne, altar and pulpit are decorated with delightful animals. The church was restored in the 16th century by Pope Clement VIII, whose coat of arms decorates the ceiling.

t Classical columns inside the church

The church of St John at the Latin Gate, founded in the 5th century, rebuilt in 720 and restored in 1191, is one of the most picturesque of the old Roman churches. Classical columns support the medieval portico, and the 12th- century bell tower is superb. A tall cedar tree shades an ancient well standing in the forecourt. The interior has been restored, but it preserves the rare simplicity of its early origins, with ancient columns of varying styles lining the aisles. Traces of early medieval frescoes can still be seen within the church. The beautiful 12th-century frescoes created by several different artists under the direction of one master, show 46 different biblical scenes, from both the Old and New Testaments and are among the finest of their kind in Rome.

t Detail of a medieval fresco in San Giovanni a Porta Latina

The name of this charming octagonal Renaissance chapel or oratory means “St John in Oil”. The tiny building marks the spot where, according to legend, St John was boiled in oil – and came out unscathed, or even refreshed. An earlier chapel is said to have existed on the site; the present one was built in the early 16th century. The design has been attributed to Baldassare Peruzzi or Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. In the mid-17th century it was restored by Borromini, who altered the roof, crowning it with a cross supported by a sphere decorated with roses. Borromini also added a terracotta frieze of roses and palm leaves. The wall paintings inside the chapel include one of St John in a cauldron of boiling oil.

t Visitors at the Columbarium of Pomponius Hylas

Known as a columbarium because it resembles a dovecote (columba is the Latin word for “dove”), this kind of vaulted tomb was usually built by rich Romans to house the cremated remains of their freedmen. Many similar tombs have been uncovered in this part of Rome, which up until the 3rd century AD lay outside the city wall. This one dates from the 1st century AD. An inscription states that it is the tomb of Pomponius Hylas and his wife, Pomponia Vitalinis. Above her name is a “V” which indicates that she was still living when the inscription was made.

The Scipios were a family of conquering generals. Southern Italy, Corsica, Algeria, Spain and Asia Minor all fell to their Roman armies. The most famous of these generals was Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, who defeated the great Carthaginian general Hannibal at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC. Scipio Africanus was not buried here in the family tomb, but at Liternum near Naples, where he owned a favourite villa.

The Tomb of the Scipios was discovered in 1780, complete with various sarcophagi, statues and terracotta burial urns. Many of the originals have now been moved to the Vatican Museums and copies stand in their place.

The earliest sarcophagus was that of Cornelius Scipio Barbatus, consul in 298 BC, for whom the tomb was built. Members of his illustrious family continued to be buried here up to the middle of the 2nd century BC.

Once mistakenly identified as a triumphal arch, the so- called Arch of Drusus merely supported the branch aqueduct that supplied the Baths of Caracalla. It was built in the 3rd century AD, so had no connection with Drusus, a stepson of the Emperor Augustus. Its monumental appearance was due to the fact that it carried the aqueduct across the important route, Via Appia. The arch still spans the old cobbled road, just 50 m (160 ft) short of the gateway Porta San Sebastiano.

t The fortified Porta San Sebastiano, the best preserved gateway in the Aurelian Wall

Most of the Aurelian Wall, begun by the Emperor Aurelian (AD 270–75) and completed by his successor Probus (AD 276–82), has survived. Aurelian ordered its construction as a defence against Germanic tribes, whose raids were penetrating deeper and deeper into Italy. Some 18 km (11 miles) round, with 18 gates and 381 towers, the wall took in all the seven hills of Rome. It was raised to almost twice its original height by Maxentius (AD 306–12).

The wall was Rome’s main defence until 1870, when it was breached by Italian artillery just by Porta Pia, close to today’s British Embassy. Many of the gates are still in use, and although the city has spread, most of its noteworthy historical and cultural sights still lie within the wall.

Porta San Sebastiano, the gate leading to the Via Appia Antica, is the largest and best-preserved gateway in the Aurelian Wall. It was rebuilt by Emperor Honorius in the 5th century AD. Originally the Porta Appia, in Christian times it gradually became known as the Porta San Sebastiano, because the Via Appia led to the basilica and catacombs of San Sebastiano, which were popular places of pilgrimage.

It was at this gate that the last triumphal procession to enter the city by the Appian Way was received in state – that of Marcantonio Colonna after the victory of Lepanto over the Turkish fleet in 1571. Today the gate’s towers house a free museum with prints and models showing the wall’s history. From here you can take a short walk along the one of the best-preserved stretches of the wall.

Haunted by the memory of the Sack of Rome in 1527 and fearing attack by the Turks, Pope Paul III asked Antonio da Sangallo the Younger to reinforce the Aurelian Wall. Work on the huge projecting bastion began in 1537. Its massive bulk can only be admired from outside.

Overlooking the Baths of Caracalla, this isolated church is dedicated to Santa Balbina, a 2nd-century virgin martyr. It is one of the oldest in Rome, dating back to the 5th century, and was built on the remains of a Roman villa. Consecrated by Pope Gregory the Great, in the Middle Ages Santa Balbina was a fortified monastery and over time has changed in appearance several times, regaining its Romanesque aspect in the 1920s. It contains many works of art.

From the piazza in front of the church, a staircase leads up to a three-arched portico. Inside, light streams in from a series of high windows along the length of the nave. The remains of St Balbina and her father, St Quirinus, are in an urn at the high altar, though the church’s real treasure is situated in the far right-hand corner: the magnificent sculpted and inlaid tomb of Cardinal Stefanis de Surdis by Giovanni di Cosma (1303).

Other features worth noting are a 13th-century episcopal throne and various fragments of medieval frescoes. These include a lovely Madonna and Child, an example of the school of Pietro Cavallini, in the second chapel on the left. Fragments of 1st-century Roman mosaics were also discovered in the 1930s. Depicting birds and signs of the zodiac, these are now set into the church floor.

Picture perfect

A highlight of a visit to the Porta San Sebastiano ramparts of the restored Aurelian Wall is the matchless views of the Appian Way and the green hills beyond , which make for a superb photo opportunity.