Fought between Napoleon’s Grande Armée and Austro-Russian forces operating in Moravia, 37 miles (60km) north-east of Vienna and widely regarded as the tactical masterstroke of Napoleon’s long military career, Austerlitz stands as one of the greatest victories in military history. A single December day’s fighting crushed the Third Coalition, with far-reaching political and strategic implications for French control in Central Europe. Austerlitz also represented a brilliant exercise in grand tactics; in the face of numerically superior forces, Napoleon encouraged Allied commanders to follow the course of action which he intended by establishing a battlefield scenario that he could control, before he proceeded to implement his plan: splitting the Allied army in half before defeating its component parts in turn.

Austerlitz is noteworthy, too, for the fact that Napoleon’s prowess and the effectiveness of the Grande Armée as a fighting force reached its apogee there, and it constituted the battle of which the emperor himself was most proud. The climax of a remarkable campaign, Austerlitz crowned the efforts of an army which demonstrated one of the key elements of strategic success: speed. The Grande Armée, poised around Boulogne on the Channel coast for the invasion of England, broke camp and in twenty days reached the Rhine; two months later it entered Vienna; and a fortnight later, under the emperor’s command, it destroyed the Third Coalition in an eight-hour engagement. If Napoleon gambled supremely in the campaign of 1805, he generally gambled correctly, partly benefitting from his own well-developed plan, as well as by the errors committed by his opponents.

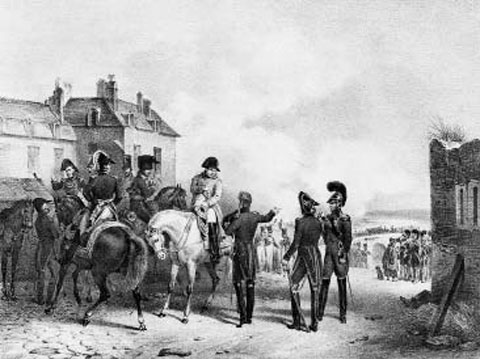

French bivouac on the evening before Austerlitz. Napoleon’s Grande Armée, at the peak of its morale and honed to a superb level of fitness and training between 1803 and 1805, constituted the best fighting force of its generation.

Austerlitz is all the more remarkable for the fact that it might very well have gone badly wrong. While it began auspiciously when Napoleon’s forces enveloped an entire Austrian army at Ulm, in Bavaria, followed by the occupation of Vienna, the Grande Armée faced a potentially perilous position by the following month, for while Austrian forces had been reduced to a remnant, the Russians managed to elude the advancing French and rendezvous with strong reinforcements near Austerlitz. Operating at a considerable distance from France, his resources stretched, facing a coalition mounting operations across a broad front, with the Prussians mobilising sufficient forces to tip the balance against him and with two Austrian armies still intact and situated to his rear, Napoleon could neither retreat for fear of its interpretation as retreat nor pursue the Allies any deeper into Austrian territory lest he risk his own encirclement and destruction. His only option lay in striking quickly and effectively, for he required nothing short of decisive victory.

With this in view, Napoleon sought to entice the Allies into fighting a battle on his own terms – using ground of his choosing and with a strong element of deception – thus compensating for the numerical advantage enjoyed by his opponents. In the event, he did precisely this, selecting an area just west of the village of Austerlitz which offered him the opportunity to design a plan to provoke the Allies into attacking on unfavourable terms. Accordingly, he sent his aide to Allied headquarters, tasked with persuading Tsar Alexander of Russia and Emperor Francis of Austria that Napoleon was anxious to avoid battle and keen to negotiate peace. Napoleon reinforced this impression of timidity by withdrawing his troops from the strategically important Pratzen Heights, west of Austerlitz. By conceding this dominant position to his opponents and by deliberately weakening his right flank, Napoleon encouraged the Allies to attack at points of his designation – all according to his elaborate plan of deception. Finally, in a calculated move, the French emperor positioned his reinforcements well back from view, leaving the impression of weak numbers – and consequently deceived the Allies into seriously underestimating French strength. A strong element of risk attended this plan, however, for success depended entirely on the Allies seizing the heights, and at the same time the French right wing withstanding the onslaught of superior numbers.

Crossing the River Inn on 28 October, French troops enter Austria. In their strategic plan the Allies certainly never envisaged conducting the campaign on home soil.

The Austrian surrender at Ulm, 20 October 1805, during the campaign in Bavaria prior to the French invasion of Habsburg territory. This and other capitulations left to the Russians responsibility for most of the Allies’ next six weeks of campaigning.

Quite apart from its significance at the grand tactical level, Austerlitz left a long-standing political legacy, eliminating the last marks of Austrian influence and territorial holdings in Germany and Italy, leaving Napoleon master of half the continent and therefore solidly on the road to establishing the greatest empire in Europe since the fall of Rome – a position achieved only eighteen months after the destruction of the Third Coalition. He consolidated his hold over Italy by annexing the last Habsburg territories in the region, adding them to the Kingdom of Italy, of which Napoleon crowned himself king, and occupied Naples, eliminating the last vestiges of resistance on the peninsula. He placed his sisters on the thrones of several German states, nearly all of which he fashioned into a new political entity: the Confederation of the Rhine, all dependent on, or subservient to, France. On this basis – quite apart from the masterful means employed by Napoleon during the Ulm campaign and at Austerlitz five weeks later – the battle led directly to a substantial shift in the European balance of power, placing France in so dominant a position as to require a further decade of fighting before the Continent could finally eradicate the menace of Napoleonic imperialism.