Chapter 4

Where Are the Customers’ Yachts?

Analyzing hedge fund industry performance isn’t as simple as it should be. For a start, there are several indices whose results can vary quite widely from month to month and their construction isn’t uniform either. For the analysis in Chapter 1, I used the HFR Global Hedge Fund Index (HFRX), which is an asset-weighted index, meaning that the return of each hedge fund is weighted by the size of that hedge fund in calculating the result. It makes sense to use such an index when assessing how investors as a whole have done, but each choice has shortcomings. Hedge funds report their results voluntarily and not all choose to disclose their size, which means only those managers willing to provide both figures can be included in HFRX.

All indices suffer from voluntary reporting, and survivor bias is a well-known problem with reported returns. Since only successful funds are going to report, a fund can easily choose to stop reporting during a string of bad results. In addition, some indices incur backfill bias; when adding a new fund to a benchmark, some index providers will “fill in” prior months’ results with the (presumably positive) results of the fund. There is plenty of academic research which seeks to estimate how much the widely used indices are distorted by this effect. Generally, estimates are in the 3 to 5 percent range (Dichev, 2009), meaning that actual results experienced by investors are probably lower than the reported indices by this amount. None of the indices referred to in this book have been modified to reflect survivor bias or backfill bias, so any overstatement of returns in those indices remains. This means that the results could be even worse for investors, but the discrepancy between what the industry has paid itself compared to what its clients have earned is already so vast that it hardly alters the overall story.

How Much Profit Is There Really?

Everybody knows the top hedge fund managers earn vast sums of money. One can debate whether the most successful managers, athletes, or actresses deserve what they get paid, but the marketplace rewards exceptional talent and always will. Frankly, after hearing John Paulson describe his enormously successful investments against sub-prime mortgages it’s hard not to admire the fresh perspective he brought and his unshakeable conviction as he bet heavily against almost the entire market. The Financial Times reported that since setting up his fund in 1994 John Paulson has made investors $32.2 billion (Mackintosh, 2010), making him the second most profitable hedge fund for clients in history, behind only George Soros at $35 billion (although his sharp reversal in fortunes in 2011 knocked him down the list). Paulson has been handsomely rewarded. The Financial Times article in 2010 was based on an unconventional view of hedge funds, highlighted by research carried out by Rick Sopher, chairman of LCH Investments. Rick has calculated how much profit the best hedge funds have made for their clients, the point being that a few dozen have produced most of the investors’ returns. The trick is, of course, identifying which ones to invest in before they produce that happy result.

While the fees earned by the top managers are presumably acceptable to their clients, the hedge fund industry in aggregate has pulled off a quite remarkable split of the profits—even more so considering how little investors as a whole have made. It’s not that hard to estimate hedge fund industry fees. Given annual assets under management (AUM) data from BarclayHedge and annual returns from whichever index provider one prefers, the standard “2 & 20” (2 percent management fee and 20 percent incentive fee) can be applied, to come up with some reasonable estimates. Not all managers charge a 2 percent management fee—many smaller funds charge 1 percent, and some larger funds charge more. The 20 percent incentive fee is reasonably standard although a profit split of up to 50 percent has been known.

However, estimating fees on the industry as if it’s one enormous hedge fund does include one simplification, in that it excludes any netting of positive with negative results. To use a simple example, if an investor’s portfolio included two hedge funds whose results cancelled out (one manager was +10 percent while the other was −10 percent) the investor’s total return would be 0 percent and for our purposes here we’ll assume that no incentive fee was paid on the 0 percent return. However, in reality the profitable manager would still charge an incentive fee. It’s not possible with the available data to break down the returns to that level of detail, so the fee estimates derived are understated, in that it’s assumed incentive fees are charged only on the industry’s aggregate profits, whereas in fact all the profitable managers would have charged incentive fees with no offset from the losing managers. The true picture is worse than the one in Table 4.1, which is already bad enough. The data goes back to 1998, simply because that’s when the BarclayHedge series begins. Given how the industry has grown since then though, the overall result wouldn’t be very different if earlier data was included.

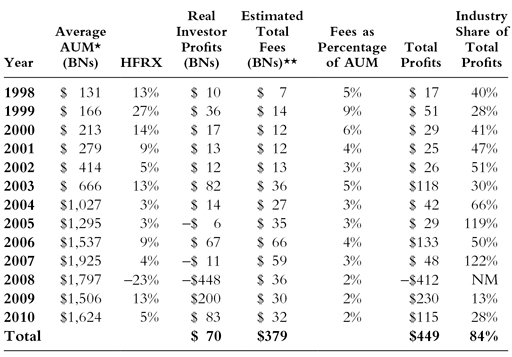

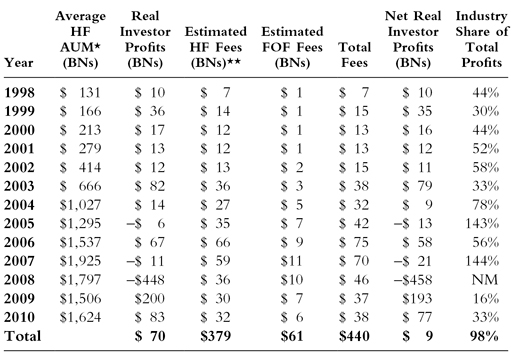

Table 4.1 Hedge Fund Returns Using HFRX

*SOURCE: BarclayHedge

**Assumes 2 & 20 with no incentive fees after 2008 since so many funds were below their high water marks.

In assessing how much investors have paid for their hedge fund love affair, there are a couple of ways to look at it. One is to express the fees paid as a percentage of overall assets, which allows easy comparison with mutual funds. The other is to look at what share of the overall profits are being returned to investors, versus those retained by the industry. In this case, excess profits over Treasury bills is the relevant measure of profits, since in years when the industry has failed to do better than the risk-free rate it can hardly claim to have generated any profits. Earning 5 percent when Treasury bills are 2 percent is a 3 percent excess return or profit to the investor, although incentive fees are normally charged on the total return. So the definition of Real Investor Profits used here is the return on hedge funds minus the return that could have been earned by investing in Treasury bills. Table 4.1 shows the results.

As a percentage of AUM, hedge fund fees have actually come down since the late 1990s. The 27 percent return in 1999 when the industry bounced back from the Russian default and collapse of Long Term Capital Management was very strong by any measure, and the normal 20 percent incentive fee led to managers keeping almost 9 percent of AUM. And in fact, the $36 billion of Real Investor Profits earned by investors in 1999 stood as their best-ever result for three years, even while the industry’s AUM more than doubled. During the 2000 to 2002 equity bear market, hedge funds really did add value as they preserved capital and this performance led to strong institutional inflows.

But the Industry Share of Total Profits has been growing steadily. To get Total Profits I’ve added fees back to Real Investor Profits, since the investors’ returns have already had fees deducted. Total Profits is how much is made before the managers’ fees are deducted. So in 1998 for example, Total Profits were $17BN ($10BN Real Investor Profits + $7BN in Fees) and so the Industry Share of Total Profits was $7BN divided by $17BN, or 40 percent.

The numbers speak for themselves. Since 1998 hedge fund managers have kept 84 percent of the profits, leaving 16 percent for the investors.

Investors Jump In

By 2003 rebounding markets, combined with a 50 percent increase in AUM, led to the industry’s best-ever Real Investor Profits—an estimated $82 billion after fees. Management and incentive fees garnered $36 billion, almost three times the prior year and 30 percent of Total Profits. This also represented the high point for investors, in that profits in subsequent years never reached $82 billion again until 2009, when the industry made back less than half of its losses from the catastrophic prior year. In six years out of 13, the industry’s earnings from fees have eclipsed or been roughly equal to the returns of its clients. In three years (2005, 2007, and 2008) it generated billions in fees while its clients lost money. Overall since 1998 fees have totaled $379 billion, compared with Real Investor Profits of $70 billion.

Fees as a percentage of Total Profits is probably the fairest way to assess the split between the industry and its clients. Over the long run, investors in hedge funds are interested in what they’ve earned in excess of the risk-free alternative and how much they’ve paid in fees to achieve that. These investment returns are also better if uncorrelated with returns from traditional assets of course, although 2008 established quite clearly that at times of extreme crisis almost all risky strategies suffer together. The net result is that the hedge fund industry has kept more than four-fifths of what they’ve made in the form of fees, leaving the investors far behind.

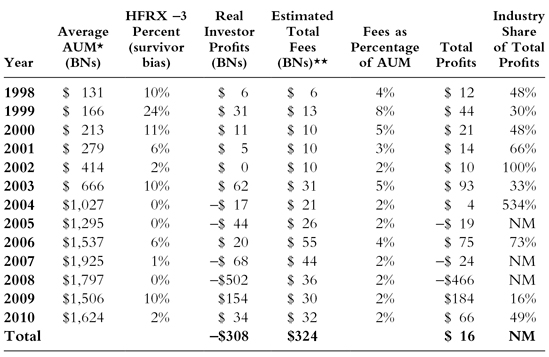

As lopsided as this sounds, it’s really even worse. The analysis above in Table 4.1 uses HFRX returns without any adjustment for survivor bias or backfill bias, which you’ll recall can cause hedge fund returns to be overstated by 3 to 5 percent. If we reduce the annual HFRX returns by 3 percent, the fees drop to $324 billion, but the Real Investor Profits earned fall to negative $308 billion, as shown in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2 Hedge Fund Returns Using HFRX Adjusted for Survivor and Backfill Bias

*SOURCE: BarclayHedge

**Assumes no incentive fees, as many funds were still below their high water marks following 2008.

No doubt the thousand-year flood that was 2008 is skewing the result, but even if the industry had been flat that year, Total Profits over this time period would have been $194 billion compared with $324 billion in fees. If the 3 percent adjustment for survivor bias used in Table 4.2 is a true reflection of what’s happened, it means that hedge fund managers have kept all the money that’s been made, and the investors have in aggregate received nothing. Remember this is simply the total; there are plenty of satisfied hedge fund clients, but the math suggests there must be many more who are unhappy or should be. And Total Profits here is calculated as the excess return over Treasury bills. Whether the HFRX return series is used, or the one adjusted for survivor bias, it’s clear that hedge fund managers have been making more from their clients’ money than their clients have.

Then there’s netting. We’re treating the entire industry like one giant hedge fund which charges a 20 percent incentive fee when returns are positive. However hedge funds that lose money don’t pay investors (i.e., there’s no negative incentive fee) and of course investors are charged incentive fees even when their overall portfolio loses. John Paulson alone was estimated by Alpha Magazine to have earned $3.7 billion in 2008 (largely incentive fees but this includes the profits on his own capital). But to keep it simple, and conservative, the calculations above assume that there were no incentive fees charged across the entire industry in 2008 because performance was negative, or during 2009 and 2010 because so many funds were below their high water marks. There’s no reasonable way to estimate the effect of this without having the returns of all the individual managers, but not adjusting for this presents the industry in a more favorable light.

Fees on Top of More Fees

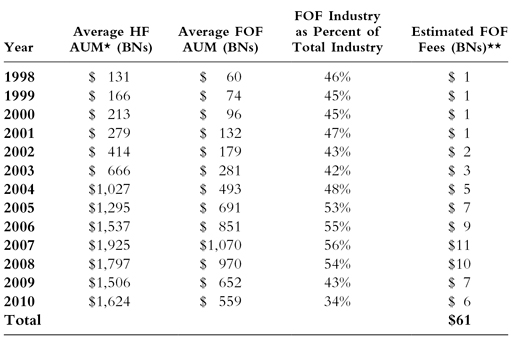

And there’s even more. The hedge fund of funds industry takes its cut too, and that’s not included yet. All the data above is based on AUM of hedge funds, but around a third of hedge fund investors make their allocations through funds of hedge funds (FOFs). In this way investors outsource the work to firms that are better equipped to handle it. Large FOFs can employ 100 people or more, covering everything from manager research and due diligence, risk management to operations, accounting, and client service. Hedge fund investing is a labor-intensive business. For investors with less than, say, $250 million to invest, it’s not worth the expense to develop their own investment staff, so they often farm it out. FOFs charge less than hedge funds, although of course their fees are on top of those charged by the hedge funds themselves. A 1 percent management fee with a 5 to 10 percent incentive fee (sometimes calculated on returns over a given benchmark) is not uncommon. For simplicity’s sake, let’s assume that FOFs simply charge a 1 percent management fee on the AUM they’re managing, with no incentive fee.

For many years the FOF industry’s growth tracked that of the hedge fund industry itself, as institutional investors outsourced their allocation decisions. However, one glaring weakness of the FOF model was revealed in 2008, in that just as hedge funds can experience sudden client redemption requests, so can FOFs. As a result, many large hedge funds prefer “direct” investors, since they know they’re dealing with the decision maker, rather than third parties such as FOFs, who may themselves experience redemptions that they have to meet. In addition, institutional investors often graduate from the FOF model to establish their own investment teams, thus retaining expertise in-house and reducing the fees they’re paying on their capital. Table 4.3 shows that FOFs have earned $61BN on top of what hedge fund managers have received.

Table 4.3 Fees Charged by Funds of Hedge Funds

*SOURCE: BarclayHedge

**Assumes no incentive fees, as many funds were still below their high water marks following 2008.

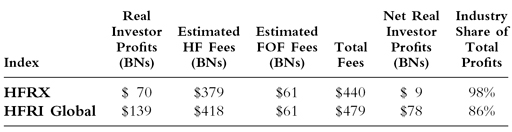

FOFs have lost market share in recent years and may have to adopt a different, lower-cost business model, such as providing consulting services. Nonetheless, while the big fees have clearly been earned by the hedge fund managers themselves, FOF managers (who are far fewer in number than hedge fund managers) fully participated in the industry’s growth until quite recently. Adding together fees charged by hedge funds and fees charged by funds of hedge funds reveals the figures in Table 4.4: Fees of $379 billion charged by hedge funds and an additional $61BN charged by funds of funds. I calculated Real Investor Profits as $70BN earlier on, but this was before deducting funds of funds fees (hedge fund fees had already been taken out). This may sound complicated—hedge fund returns are calculated net of hedge fund fees, so we know that set of fees has already been deducted. I estimated Funds of Funds fees based on the amount of assets they’re managing. For those investors using FOFs they’re paying fees on top of fees, so FOF fees have to be deducted from Real Investor Profits to see what’s actually left, This is the Net Real Investor Profits column. After paying these fees as well, investors are left with $9BN. Between hedge funds and funds of funds investors have been charged $440BN, eating up 98 percent of whatever profits have been made.

Table 4.4 Everybody’s Fees

*SOURCE: BarclayHedge

**Assumes no incentive fees, as many funds were still below their high water marks following 2008.

Even this doesn’t fully capture the cost/benefit tradeoff. Many U.S. institutional investors rely on consultants to advise them on their hedge fund portfolios. Consultants typically don’t have a fiduciary relationship with their clients, but they do provide specialized knowledge, both on the industry and on many of the larger managers. For most institutions, use of a consultant provides a convenient legal liability shield for the investment committee if things go wrong, in that they can point to an independent third party’s recommendations when explaining investment results to their sponsor. There’s no easy way to estimate aggregate consulting fees—they range from as little as 0.05 percent of assets to as much as 1 percent. But the numbers as presented here offer a sufficiently clear story, and in all likelihood they understate the ultimate costs paid by investors (and therefore overstate the net profits earned by those same investors).

All the figures in Table 4.4 use the HFRX, an asset-weighted index. This index was chosen because the purpose is to calculate aggregate investor returns, so an index that reflects the relative size of hedge funds is arguably most appropriate. It’s also a investable index, meaning that it is possible to earn its return should an investor be so inclined. However, the story is substantially the same using the HFRI Global Index as shown in Table 4.5. Any way you cut it, hedge funds have been a fabulous business and a lousy investment.

Table 4.5 Comparing Different Indices 1998 to 2010

The hedge fund industry is global, so this isn’t simply a case of Wall Street keeping more of the spoils, although the United States and United Kingdom represent a substantial chunk of the industry. Nevertheless, what investors have paid compared with what they’ve received is almost breathtaking. Hedge fund managers, advisers, consultants, and funds of hedge funds have succeeded in generating substantial profits. However, they’ve also managed to keep most of these gains for themselves, while at the same time successfully propagating the notion that broad, diversified hedge fund allocations are a smart addition to most institutional portfolios. That’s quite a trick!

Drilling Down by Strategy

The hedge fund industry breaks down into separate strategies, such as long/short equity, relative value, distressed debt, global macro, and so on. Using AUM figures for each strategy, it’s possible to estimate which have provided the most egregious mix of fees and (non) performance for investors. Remember, all this analysis is being done using publicly available data. It’s just that it has rarely, if ever, been done this way. Hedge fund industry advocates have chosen to focus simply on annual average returns, without looking at gross profits or how those profits are split between clients and the industry.

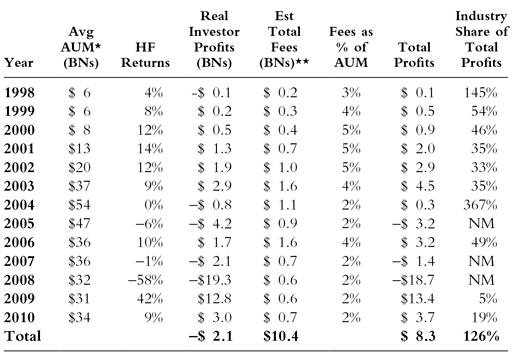

So using the same technique, while drilling down to the strategy level, reveals the following numbers shown in Table 4.6 for convertible arbitrage. The AUM figures on convertible arbitrage funds are from BarclayHedge, and the returns are from the HFRI Convertible Arbitrage Index. All figures, apart from annual returns, are expressed in billions of dollars.

Table 4.6 Convertible Arbitrage Hedge Funds Fees and Profits, 1998 to 2010

*SOURCE: BarclayHedge

**Assumes 2 & 20 with no incentive fees after 2008 since so many funds were below their high water mark

Hedge funds specializing in convertible arbitrage have earned more than $10 billion in fees since 1998. This figure is the low end of the likely range, for the same reasons as the industry-level figures shown in Table 4.1; it treats the industry like one big hedge fund. Therefore in a year when returns are positive it assumes the industry charged a 20 percent incentive fee, whereas in reality the profitable funds charged a fee, but the unprofitable funds didn’t provide an incentive fee rebate. Accordingly, in any given year, incentive fees are likely to be more than 20 percent of profits, depending on the mix of winners and losers.1 And in 2009 and 2010, we’ve assumed no incentive fees at all across all convertible arbitrage funds, following the disastrous results of 2008, since most managers were below their high water marks. In reality though, it’s likely that incentive fees were above 0. Any new inflows after 2008 were probably subject to incentive fees.

Compared with the $10.4 billion in fees earned by convertible arbitrage funds, investors actually lost $2.1 billion. They did worse than Treasury bills, while paying a substantial amount for the privilege. As with many things, the 2007 to 2008 credit crisis significantly impacted results, but even up until 2006 the split was: $7.7 billion in fees versus $3.6 billion in Real Investor Profits. In normal times, convertible arbitrage funds and their clients had settled on a roughly 70:30 split in favor of the managers.

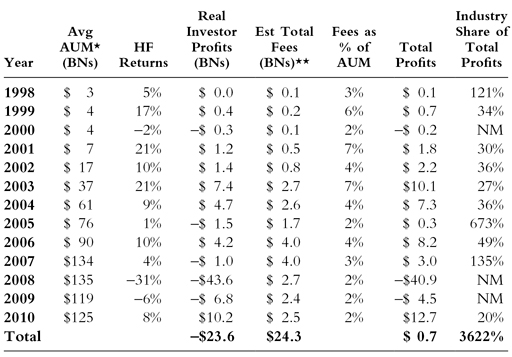

Distressed debt provides a similar story as shown in Table 4.7—Real Investor Profits, what investors have earned in excess of riskless Treasury bills, are solidly negative.

Table 4.7 Distressed Debt Hedge Funds Fees and Profits, 1998 to 2010

*SOURCE: BarclayHedge

**Assumes 2 & 20 with no incentive fees after 2008 since so many funds were below their high water mark

Next time you find yourself in a social setting with anybody from the hedge fund industry, you can entertain yourself and others by asking this simple question: Name a hedge fund client who has made a substantial amount of money by being a hedge fund investor. Note the word client is key here and the question deliberately excludes hedge fund managers themselves, managers of funds of hedge funds, consultants, or anyone who’s in the business of making a living from fees charged on hedge fund investments. We’re looking for pure investor clients. I started playing this game recently at gatherings of hedge fund professionals, and I can tell you the responses are quite amusing. Once people understand that George Soros isn’t an acceptable answer, they stare quizzically at the ceiling while racking their brains for someone, anyone, who’s come out ahead. At times I’ve felt embarrassed, as if I’m asking someone to name the President of the United States and they’ve drawn a momentary blank. It shouldn’t be much more difficult—after all, there are plenty of clients and some of them must have done well. And of course there are successful hedge fund investors, but the trouble so many industry professionals have with this innocuous question and their evident discomfort as they struggle to come up with names reveals more of the inconvenient truth about the hedge fund business than many would like.

Hedge fund managers are rational businesspeople, as well as often being talented investors. As in any free market economy, the provider of a service will seek to maximize his profits in part by raising prices, until competition and sagging demand indicate resistance. In the case of hedge fund managers, the “price” is really the split of total trading profits that investors require in order to remain as clients. The split of profits has been steadily shifting in favor of the hedge fund industry, because investors have broadly accepted steadily worsening terms. Fees charged are high by almost any reasonable standard, but willing buyers (clients) and sellers (hedge fund managers, funds of hedge funds, and consultants) continue to do business at prevailing rates. If consumers continue to pay higher prices for something, it’s hard to blame the retailers, who are simply meeting that need. However, in this case the consumers are sophisticated institutional investors and one might think they’d be pressing for more equitable terms.

There are numerous academic articles on the hedge fund industry covering a wide range of topics. Papers have been written on whether hedge funds truly deliver alpha (in layman’s terms, do they really make money once you properly account for the risk they take); on whether small, new hedge funds do better than older, established ones (they generally do); and on the impact fees have on managers’ behavior. One common problem for investors occurs when a small fund enjoys strong success from a strategy that can only absorb a limited amount of capital. New clients flock to the high-performing fund, and eventually the increased level of AUM overwhelms the liquidity in that particular market, making it hard to generate the higher returns of the past.

“Is Pay for Performance effective? Evidence from the Hedge Fund Industry” is a research paper originally published in 2007 (updated in March, 2011) by Bing Ling and Christopher Schwarz, (you can find it at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1333230) which examines this issue systematically. The typical 20 percent incentive fee is supposed to ensure the manager is focused on generating consistently strong performance. In passing, the authors compare the pay-for-performance link managers enjoy with corporate executives. Senior managers of U.S. corporations are often described as overcompensated, relative to the value they create for shareholders. However, they are in the minor leagues compared with hedge fund managers; for a given amount of wealth created for shareholders (or in this case hedge fund investors) hedge fund managers retain around 30 times the share that corporate executives earn! Who would have thought CEOs were so underpaid?

Ling and Schwartz go on to examine whether hedge funds stop taking clients (in industry parlance, they “close” to new money) when they have reached whatever capacity limits their strategy faces. One might think that the incentive fee would be a powerful reason to do just that, since lower returns generate lower incentive fees. But in fact, the data shows otherwise. Many managers reach capacity some time before closing to new money, and in addition, once they’ve closed their returns are usually not as good as in the past. It’s as if the strong commercial instincts of many managers trump maximizing overall returns. But the authors go on to find that managers who allow their AUM to grow too big are still acting rationally, (i.e., maximizing their own profits) because they’re able to charge incentive fees on an even bigger pool of capital. If AUM grows faster than returns fall, the manager is still ahead of the game.

Table 4.8 illustrates a simple case. At $1BN in AUM the strategy generated a respectable 10 percent return. At $2BN returns fell to 7 percent, but even though the incentive fee dropped, the greater AUM resulted in higher overall fees.

Table 4.8 Why Some Hedge Funds Grow Too Big

| Right Amount of AUM | Too Much AUM | |

| AUM | $1BN | $2BN |

| Returns | 10% | 7% |

| Incentive Fee at 20% | 2% | 1.4% |

| Incentive Fee | $20MM | $28MM |

This example of course doesn’t include the 1 to 2 percent management fee which, to the extent it’s not all used to run the business, adds to the manager’s personal profitability. The paper concludes with the dry observation that “hedge fund managers have a profit maximization function consistent with hoarding assets.” In other words, their interests are ultimately best served by growing their business as large as they can, though few managers ever admit that.

How to Become Richer Than Your Clients

It can be interesting to look at individual hedge funds and see how they did. BarclayHedge maintains an extensive database on returns and AUM for a subset of the hedge fund industry, and from this it’s possible to go fund by fund. III (Triple I, originally known as Illinois Income Investors) is one of the oldest hedge funds around. It has a continuous track record that dates back to 1993. It is a fixed-income relative-value fund, which means it trades mortgage-backed securities, interest rate swaps, and other related instruments. They are “picking up pennies in front of the steamroller,” in industry parlance, which is to say they identify minor pricing discrepancies and then exploit them profitably through the use of leverage.

I remember meeting one of the principals, Warren Mosler, sometime in the 1990s. Warren struck me as very smart if somewhat eccentric. He was pursuing a hobby of building super-fast sports cars with some of his growing wealth. He seemed somewhat bored with the business, commenting that every year his W-2 was doubling in a way that suggested the whole business was failing to challenge him. Warren had a curious theory of money’s role in an economy, which I found hard to follow, but he asserted that the government’s role in imposing taxes was a necessary requirement for money to have any actual value (since citizens needed it to pay taxes) and that if the government didn’t tax, money would lose its value. For a while afterward he sent me research papers on the topic, though I must say I never fully grasped his insight. III had a spectacular office in West Palm Beach, Florida, facing out over the Atlantic Ocean. It was an idyllic setting and an enviable lifestyle. III went on to many years of success which continues today.

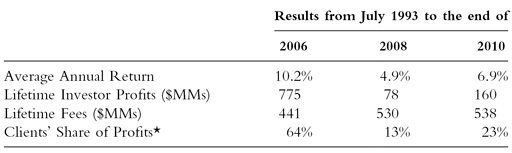

Using the available data, it’s possible to estimate investor profits and fees generated over quite a long period of time. These figures are estimates based on AUM and returns. The actual profits earned by III and its clients are private. Table 4.9 is illustrative.

Table 4.9 Why Hedge Funds Are Such a Great Business

SOURCE: BarclayHedge

*Since client profits are net of fees, adding fees back to client profits results in total profits. So through 2006 for example, total profits were $775 + $441 = $1,216. The clients kept 775/1,216, or 64 percent.

Over 14 years, from 1993 to 2006, III generated an average annual return of 10 percent, producing more than three quarters of a billion dollars in cumulative investor profits. They still managed to haul in more than $400 million in fees for themselves, resulting in clients keeping just less than two thirds of the total profits generated. Because III had grown so large, by the end of 2008 following the worst of the credit crisis, virtually all the profits clients had ever earned from III were gone, although by then the managers had taken their winnings to more than half a billion dollars. As markets recovered, investors made back some of their money, but the end result is still that for one of the longest-lived hedge funds that has delivered generally steady results for nearly two decades, the clients have kept less than a quarter of the trading profits generated. This analysis only covers one of III’s funds; they have others. The results are similar, and the principals have become very wealthy. The interesting question is whether the wealth created by the owners has been earned by adding commensurate value to their clients, or did a set of industry investors hand over substantial sums while receiving very little in return.

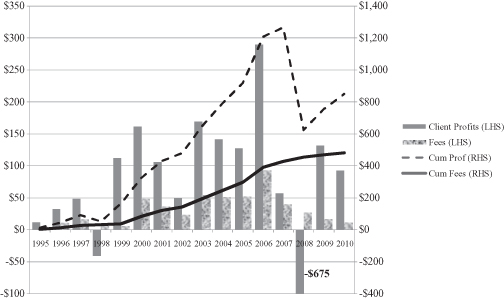

Stark Investments is another old hedge fund that presents a similar story. From 1995 to 2007 (see Figure 4.1), using the same calculation assumptions as for III, Stark earned $428 million in fees while its clients earned $1.26 billion. Stark’s managers retained 25 percent of the total trading results while their clients kept 75 percent. In 2008 trading losses wiped out half of all the profits the clients had ever earned, and perhaps not surprisingly Stark’s business began to shrink. By 2010 Stark’s cumulative fees had reached $480 million and the clients had netted $848 million. This was a better split with clients than for III, but still not great. If the clients’ money had been invested in Treasury bills throughout this entire period they would have earned $490 million. Stark added $358 million in additional value which works out to be less than 2.5 percent per annum over the risk-free rate and they earned nearly half a billion dollars in the process.

As with all hedge funds, the fees kept growing (the dashed line) even when the results turned down. The contrast between client success and what they paid for it is, well, stark.

Summary

Sir Winston Churchill, Britain’s inspiring leader during World War II, gave many stirring speeches and provided the English language with numerous memorable quotes. In 2002 the BBC broadcast a documentary called “100 Greatest Britons,” and by popular vote Churchill was named the Greatest Briton (even ahead of David Beckham). Following the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940 when the Royal Air Force held off the German Luftwaffe in the skies over southern Britain scuttling Hitler’s planned invasion, Churchill praised his gallant fighter pilots with the words, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

Presented with today’s hedge fund business, Churchill might comment that, “Never in the history of Finance was so much charged by so many for so little.”

There are and always will be some fantastically talented hedge fund managers. Sadly though, for the industry as a whole, it appears that their investment acumen is not as keen as their commercial instincts. The investors who have made this possible owe it to the pension fund beneficiaries and other hapless providers of capital to improve their outcomes.

Note

1 To illustrate with a simple example: suppose an investor has two hedge funds, one of which earns $5 million in profit while the other loses $2 million. The profitable hedge fund will charge an incentive fee of $1 million ($5 million × 20 percent) while the losing fund will not charge one. In this way, gross profits of $3 million ($5 million − $2 million) will generate an effective incentive fee of 33 percent ($1 million fee divided by $3 million profit). The investor’s net profit will be $2 million.