Chapter 6

The Unseen Costs of Admission

The hedge fund net asset value (NAV) is the price at which investors enter and exit. The fact that it is a single figure (i.e., inflows and outflows occur at the same price even if they don’t offset each other, which they rarely do) makes it appear a much more precise measure of value than is often the case. It also takes no account of the costs incurred by a fund whenever new money needs to be invested or capital raised to meet redemptions. In fact the whole subject of transaction costs is one that’s rarely visible to the investor. Hedge funds pay enormous amounts of commissions and incur additional market impact costs whenever they cross the bid/ask spread. In many markets, the cost of the bid/ask spread can be substantially more than commissions, but it’s not directly observable by the investor.

Consider a hedge fund investing in corporate bonds needing to invest additional capital received from a new investor. The quoted market amongst bond dealers for one of the bonds the hedge fund needs to buy might be 80-81 (i.e., bid at 80, offered at 81). If no motivated sellers are around, the hedge fund would buy the bonds from a dealer at 81, and assuming no actual change in prices, the closing value on those bonds would be 80.5 (mid-way between the bid and offer). The hedge fund’s newly acquired bonds would be valued at 80.5, showing a 0.5 point loss which was the result of the transaction costs of deploying new capital. Because hedge funds are commingled vehicles, meaning that all the investors’ capital is managed in one large pool, the cost of investing this new capital is borne by all the investors in the fund proportionate to the amount they have invested. Transaction costs are socialized, and are rarely shared equitably across all investors. It’s very hard for any hedge fund investor to measure this, not least because NAVs are usually produced monthly and it’s not a trivial task to measure that kind of detail. And market-impact costs are themselves imprecise estimates; in this case, the hedge fund’s buying may force the price up to 81 bid, 82 offered, muddying the assessment of whether there was a true cost to the hedge fund.

However, over large numbers of transactions the market-impact costs will average out—indeed, they really have to, since the dealer’s profit in quoting a two-way market in those bonds is the bid/ask spread. It’s their fee for providing liquidity, for holding inventory and being a counterparty to the trade. The trading profits of large Wall Street banks are often the market-impact costs for hedge funds, particularly in bonds and foreign exchange where no formal exchange exists. This is in part how JPMorgan’s Rates business or Goldman’s FICC (FX, Interest rates, Commodities) generate so much revenue. For example, in 2010 JPMorgan’s Investment Bank generated $15 billion in revenue in Fixed Income (within which they include Foreign Exchange and Commodities), following $17.5 billion in 2009 when markets were bouncing back from the credit crisis (in 2008 revenues collapsed to only $2 billion). Since bonds and FX do not generally trade on an exchange, these revenues are largely from acting as market maker to clients and counterparties, including hedge funds. Goldman’s equivalent business (FICC) generated $23 billion in 2009, approximately half of the company’s total revenues and a record. Markets recovered strongly but liquidity hadn’t yet fully returned, which created the perfect environment for market making. Following the public outcry over Wall Street profits, Goldman stopped breaking out their results this way in 2010.

How Some Investors Pay for Others

I had an opportunity to see firsthand how trading impacts the performance of a hedge fund and how those costs are inequitably shared. In 2003 we invested in a market-neutral hedge fund run by Peter Algert and Kevin Coldiron, Algert Coldiron Investors (ACI). Peter and Kevin had both worked at Barclays Global Investors (BGI), one of the best-known users of quantitative models to invest in large, highly diversified portfolios of equities. Peter and Kevin had decided to leave and set up their own firm, and we agreed to provide the initial seed capital to start their fund. Peter has a PhD from UC Berkley and headed research, while Kevin was in charge of portfolio management. Our provision of seed capital to their new fund gave us a share in the fees they would earn on all subsequent investors, common practice in such situations.

If they could grow the fund, the return on our investment could be augmented substantially through this fee-sharing. Kevin and Peter are both terrific guys. Kevin had spent some time living in London while with BGI and had an MBA from the London Business School, so he had some familiarity with England’s national sport and my team Arsenal. Over the years Peter and I had gone skiing together with other members of ACI. We were invested with ACI for seven years until the terms of our fee-sharing arrangement expired. It wasn’t all a walk in the park, and 2007 to 2008 was obviously particularly difficult. But the two of them were unfailingly professional and hard-working, that rare combination of talented investor and driven business builder. Our investment with them was in total a good experience.

In May 2003 the fund was launched, with $25 million of capital from JPMorgan. One of the benefits of being a seed investor is that you can often negotiate advantageous terms, and amongst the many things that we required was complete transparency of the portfolio on a daily basis. This meant that we could see all the trades they did and the daily profit and loss (P&L) so that we could monitor our investment almost as closely as ACI could themselves. I was somewhat startled on reviewing the first day’s trading results to see that we were down 0.48 percent. While not a substantial loss, for a one-day change in value it was still pretty significant. Market-neutral investing as explained to us by Kevin and Peter involves a great deal of quantitative analysis to arrive at a portfolio of longs and shorts that’s highly diversified and is designed to extract a very small edge or alpha across a large number of positions. Losing almost half a percent in one day seemed at odds with this.

It quickly became clear as we discussed the first day’s results with Kevin that the commissions and market impact costs of investing in several hundred small-cap stocks was largely responsible. As a “quant” shop, ACI was well armed with some fairly sophisticated analytical tools, and they were quickly able to break down a single day’s result into its various components. Our conclusion was that it was a one-time event, an unavoidable consequence of investing our capital. The portfolio would of course require regular rebalancing as prices moved and their models gave new signals, but nothing that would compare with the initial start-up.

At the end of the month, ACI received its first “non-seed” investment, of another $25 million bringing the fund’s size to $50 million. This was a solid start and the early feedback from many other investors who were watching ACI and considering their own investment in the fund was largely positive. We all felt very good about near-term prospects for growth. On the first day of the second month, unsurprisingly, the fund was down around 0.24 percent. The new $25 million had been invested, and had incurred transaction costs similar to those we had examined on our own first day. But because we were in a commingled vehicle, we were bearing our share of the costs of the new money coming in.

In fact, it doesn’t take much thought to realize that in any fund the early investors pay for a disproportionate share of the market-impact costs. The bigger your share of a fund, the more your own investment will pay the freight. An early investor can wind up losing quite significant value through this sharing of transaction costs. And of course, needless to say, the process repeats itself on the way out. If a fund is shrinking and you happen to be one of the last to leave, you’ll be paying a greater share of the expense of those leaving, as securities need to be liquidated in order to generate cash to meet redemptions.

This is one of the little-known secrets of the hedge fund business. Hedge fund managers understand this issue all too well. Their investors rarely do. While many investors will have a conceptual understanding of transaction costs, they rarely spend much time focusing on it, not least because it’s hard to obtain accurate information. However, few hedge fund investors have stopped to think about how the timing of their investment in a hedge fund as well as their percentage of the overall fund will affect their own results as others investors come and go. The open-ended structure of hedge funds, with its commingled assets, is what makes this possible. It’s very convenient for everybody as long as the investors don’t look too closely. And hedge fund managers have little reason to go into what can be an arcane topic. But this is why mutual funds, with their open-ended structure, place constraints on frequent withdrawals or in some cases charge investors fees when they invest to cover the expense of investing their capital.

This problem only became clear to me as a result of seeing the daily results of ACI. This is why so few investors are familiar with it, because they don’t have the opportunity to watch a hedge fund’s daily activities in such a close-up fashion. Growth in ACI was going to be a drag on our performance through these shared transaction costs. Over time the effect would become less significant as their assets grew and the costs were spread over a larger pool of investors. And of course in our particular case because we had negotiated a share of the fees they earned from all their other clients, overall we stood to benefit dramatically from their success. The fee-sharing benefit was worth substantially more than the shared transaction costs. But our situation was unique—all the other investors, including the $25 million that followed a month after launch, would suffer these costs inequitably; not based on what it had cost to invest their capital, but instead based on when they invested and the decisions of others. The costs are shared unevenly.

ACI’s structure was utterly normal. There was nothing wrong in how the fund was set up or managed, and thousands of hedge funds operated the same way and still do today. For my part, believing that the hedge fund industry might benefit from an improvement, we persuaded ACI that they should charge investors a fee for entering and a fee for leaving. The fee (typically 0.5 percent) would be based on the likely cost of investing new money or raising cash to meet a redemption, and would naturally be paid to the fund and not to the manager. In this way, the entry/exit fee would offset the transaction cost and result in a more equitable sharing of costs. Such an arrangement was very unusual but other hedge funds have adopted the practice. AR magazine (“Paul Singer’s Elliott Management, which has had a bang-up year, is instituting a performance fee for the first time,” 2009) noted in 2009 that Paul Singer’s $16 billion Elliott fund had been charging a 1.75 percent entry and exit fee to investors, presumably to defray the costs of deploying new capital (for new investors) or raising cash (for redeeming investors).

Kevin and Peter were somewhat uncomfortable only because they felt it would be a difficult issue to explain to new investors, but they agreed to go along because they understood the unfairness of the current system and felt, as I did, that it was worth trying to fix. But they did find the vast majority of investors failed to initially grasp the concept. Most investors thought it was simply a fee that would hurt their returns, and didn’t fully appreciate the idea was simply improved fairness. These transaction costs were happening to the fund anyway regardless of whether or not there was an entry/exit fee. I had hoped that we might begin a trend toward more fair and open treatment of hedge fund investors, but I have to concede that few hedge funds saw the need to change and few investors demanded it. If hedge funds were operated as closed end vehicles like private equity and did a single round of fund raising, everybody would be treated fairly. Alternatively, separately managed accounts ensure that each investor absorbs only the costs related to their own investment because they’re not in a commingled pool with others. Both would be an improvement.

My Mid-Market or Yours?

How market-impact costs are allocated should be an important issue for every hedge fund investor. But the NAV itself, the value at which investors enter and leave the fund, can be manipulated in ways that are rarely clear to either current or prospective investors. The first thing is that “mid market” or “fair value” are by their nature only good-faith approximations of value. In every market the price at which participants can buy is different from where they can sell; how different they are is a basic measure of how liquid a particular market is. A hedge fund could have two NAVs, one for redeeming investors (the “Bid NAV”) based on where the manager can liquidate securities to provide the necessary cash, and one for new investors (the “Ask NAV”) reflecting the costs of deploying new money. The difference between the two would be approximately equal to the liquidity of the hedge fund’s underlying investments. It would be a bit cumbersome, but would make explicit what is currently only implicit in reported results. For hedge funds investing in large-cap public equities, developed market government bonds, or foreign exchange, bid/ask spreads are small and the Bid NAV and Ask NAV would be quite close to one another—maybe 0.25 percent or so. Hedge funds in corporate bonds and small-cap stocks might use a spread of 0.5 to 1.0 percent. And the amount of leverage employed would also play a role.

It’s helpful to illustrate with an example. Consider two hedge funds that invest in convertible bonds. One has no leverage and the other employs leverage of 5 to 1, which is to say for every $1 it has in capital from clients it borrows an additional $4 and buys $5 in bonds. To make it simple, we’ll assume that each fund only holds one bond, and the price of that bond with dealers in the marketplace is 99-101 (i.e., can be sold to a dealer at 99 or bought from a dealer at 101). Conventionally, the hedge fund would mark to market its portfolio (of a single bond in this case) at mid market or 100. However, in many cases as long as the bond is valued in between 99 and 101 that would be defensible as a “fair value” for the security. That would be sufficiently precise, “good enough for government work” and if all that’s being done is to provide a valuation it’s very reasonable. However, transactions take place based on a hedge fund’s NAV every month, and an investor has as much stake in a correct NAV as he does in buying any other investment at a fair price.

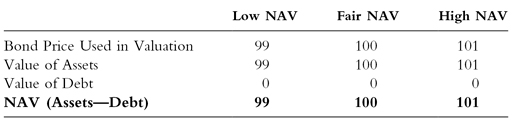

Table 6.1 shows how the reported NAV of the hedge fund could vary depending on where within the 99-101 bid/ask spread for the bond it is being valued.

Table 6.1 Unleveraged Hedge Fund

In this simple case, of course the stated NAV of the hedge fund directly reflects the price used to value the bonds. The NAV can vary by 2 percent, which is the same as the range between bid and ask for the bonds held by the hedge fund.

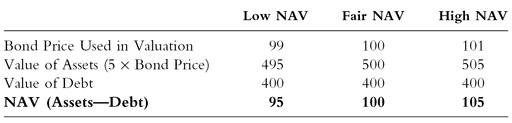

Now let’s look at the same math in the case of a hedge fund leveraged at 5:1, not uncommon in the convertible bond market, shown in Table 6.2.

Table 6.2 Leveraged Hedge Fund

The leverage magnifies the sensitivity of the NAV to the price being used to value the bonds. Quite small differences in bond valuation, when viewed through the prism of leverage, can create as much as a 10 percent difference in NAV. As long as the bonds are being valued within the bid/ask spread, which is to say within a normal range, there’s really nothing wrong. However, for an investor putting capital into the levered fund or redeeming from it, the difference is certainly not trivial. While the example is obviously simplified so as to illustrate, the point is nevertheless that investors have a very real stake in how the NAV is calculated. Less-liquid securities are more prone to this type of manipulation.

It’s unlikely to be consequential for developed market equities (other than perhaps small cap), sovereign debt, or foreign exchange. Corporate bonds of all credit types including mortgage backed securities are where the potential for abuse exists, and the use of leverage (as shown above) can exacerbate the range of plausible NAVs quite dramatically. Probably the best that an investor can ask is that it be done consistently and most logically at the middle of the bid/ask spread. However, it’s a rare hedge fund Private Placement Memorandum (PPM) that will define with such precision how this should be done, and in some cases it is ripe for abuse.

The Benefits of Keen Eyesight

In 2004 we met Howard Needle and David Harris, managers of Acuity Partners, a convertible arbitrage hedge fund. Howard and David had worked together before at Bank of America, and Acuity had been in business about six months by the time we met. Howard was the more personable of the two, and for good reason was more focused on marketing and describing their strategy to clients and prospects. David’s manner was somewhat brusque, intending perhaps to be a little intimidating. In short, he was a typical trader—opinionated, strong-willed, but also smart and quite likable as you got to know him better. After spending some time with Howard and David over a period of weeks we felt their prospects were good. They just needed some additional capital to supplement what they had started with, which was largely their own money. We negotiated a seed investment in exchange for a share of the fees on future asset flows.

After a solid start, their performance began to lag. They had produced some strong results in their early months when they were small, but the convertible bond market’s rally had lost its energy and as the months passed Acuity was steadily doing worse than its peers. Seed investors sometimes agree to lock up their capital for an initial period of time, so as to guarantee stable capital for the hedge fund manager. At the same time, to protect the investor in the event that performance is just terrible and he wants to exit early, there are typically minimum performance targets that the investor and hedge fund agree upon from the outset. We had agreed to lock up our capital with Acuity but had negotiated the ability to exit early if their performance was particularly weak. During the first few months of 2005 they continued to struggle, and much as we wanted them to succeed we were starting to worry about the trigger on our early exit provision. By May, the convertible bond market was seeing increasingly heavy selling, and even though Acuity was running a hedge fund they were not able to hedge against falling bond prices and their losses accelerated.

In early June we had a meeting of our investment committee and decided that we had little choice but to exercise our escape clause. The HFRI Convertible Arbitrage Index was already down 6.5 percent for the year, which doesn’t sound like much compared with a bad period for stocks but was by far the worst period of performance in its history. Convertible arbitrage was about hedging away market risk and extracting modest but regular profits. The market was in complete disarray.

David tried to convince us that the timing was bad—and indeed the market had continued to deteriorate. However, in our original fund raising discussions with investors we had carefully described the provisions we intended to negotiate with new hedge fund managers, including the ability to extricate ourselves from a lock up on our investment. We felt that, while the timing was not great, we had an obligation to follow through on an element of our risk management, and we put in a redemption notice on 50 percent of our capital. The terms of our investment allowed for an intra-month redemption. Since an official NAV from the administrator was required on which to calculate the proceeds owed to us, the administrator duly calculated the fund’s value based on the bond prices provided by Acuity.

Our investment had lost several percent in value in just a few days from the end of May when the last NAV was calculated, until the date of our redemption. This is where the seed investor’s ability to access actual positions and trades is so critical to truly understanding what transpired. We complained bitterly to Howard and David about the sharp drop in value. They pointed out how weak and illiquid the market had become, conditions that were at their most dire at precisely the time we were exiting. We felt that the bond prices used had been unfair, and in response David sent us a spreadsheet listing detailed quotes that he had received from various dealers. As we analyzed the data, we began to understand what had taken place. We had daily valuations on Acuity’s portfolio and compared them with the daily values of the convertible bond market.

The results were eye-opening. Through late May and into early June, Acuity’s daily values had tracked the broader market indices reasonably well. Then, at the time we communicated our intention to redeem until the point five days later when the precise NAV was calculated, Acuity’s valuation had deteriorated much faster than the index. On the precise day that half our capital was redeemed, the gap between Acuity and the benchmark was at its widest. In the days following the difference narrowed as Acuity’s fund value retraced its steps. David Harris had even provided us with a spreadsheet from the day the relevant valuation was done, and more often than not the bonds Acuity owned were being valued on the bid side of the quoted dealer market, rather than at mid market. The valuation of their portfolio had been biased down at the moment it would reduce the value of our redeeming investment, and then allowed to return to its normal level.

We told David what we believed had happened, and that we felt we’d been treated unfairly. He was outraged, and strongly argued that they’d done nothing wrong. The market had been exceptionally weak, and he was pricing conservatively. What made it worse was that although he’d used bond prices close to or on the bid side of available quotes, in many cases they had chosen not to sell bonds at those prices. They were able to do this because they didn’t need to raise cash to return our capital. The fund already had sufficient cash to pay us out. So our redemption value had been calculated on the basis of sharply depressed prices even though Acuity never had to sell bonds at those prices. In effect, using the example of the leveraged hedge fund earlier in the chapter, they had valued the portfolio using a bond price of 99 but never sold any bonds at that price. Our loss from receiving less than we should have from our redemption was the gain of the rest of the investors in Acuity, including of course Howard and David.

We never agreed on the issue. We felt very badly treated; Howard and David were adamant that the entire process had been fair. We had been exposed to the hedge fund manager’s ability to value the portfolio, and even though the valuation was always defensible legally as being within the bid/ask spread of the underlying bonds, we felt we’d been had. Fortunately, we were able to turn the trick back on them two months later. Convertible bonds rebounded sharply, and Acuity began a dialogue with several investors about quickly investing while compelling values were available. We still wanted to withdraw the other half of our capital, and we guessed that to the extent they could bias their NAV higher or lower by late August, they’d want it to be higher to emphasize the strong recovery in their performance following the market’s early summer slump and rebound. To return to the leveraged hedge fund example, with the possibility of new inflows and with investors paying close attention to their monthly performance, we thought they’d more likely value bonds at 101 rather than 99. We were right, and our final redemption in late August was at buoyant prices since we’d identified where we could align our interests with the manager.

Acuity did nothing wrong in legal terms. The bonds in their portfolio were, as far as we could see, valued within the bid/ask spread. The fund’s documentation on valuation required no more, as is usually the case. Some hedge funds will assert that they value their holdings on the bid side because this is more conservative. It does produce a lower NAV, and therefore a lower and more conservative valuation for existing investors. However, this should be false comfort because it also means that new investors come into the fund at a “conservative” (which means low) NAV. Since the new capital received will have to be deployed, the manager will either have to buy more of the securities already owned, incurring transaction costs shared by all the investors, or use the cash for new opportunities which has the effect of diluting the existing investors’ share of current holdings at the bid side of the market. In effect, existing investors sell a pro-rata share of their holdings to the new investors at the bid side of the market, hardly fair if there exists a 1 to 2 percent bid/ask spread. My central point to Acuity had been that whether they typically valued securities at the bid side of the market or at mid-market, they ought to be consistent. Switching methods depending on whether investor flows were into the fund or out of the fund was not right.

Subsequently I had some fascinating conversations with other hedge fund industry investors about whether what they did was right or not. People are very confused about this issue—my conclusion was that it’s not well understood by most investors. There’s a view that, if bonds have to be sold to meet a redemption then the portfolio should be valued using prices where those sales took place. The logical corollary is that if there are inflows the bonds in the portfolio should be valued at prices where additional securities could be bought so as to maintain consistent exposures with the new money. Others felt that it really depended on whether or not Acuity had decided to sell to meet our redemption or had instead elected to use cash already on hand, thus increasing the risk of the portfolio to the remaining investors at a highly advantageous time. There was no consensus and this is because the issue is not well understood as well as being unique to hedge funds.

The combination of an open-ended fund structure, allowing inflows and outflows without having to create a new legal entity, combined with less than highly liquid underlying investments, creates all kinds of opportunity for the manager to just shade the valuation in the direction most beneficial to him. The use of closed end funds, separately managed accounts, or entry/exit fees are all solutions that would ensure fair treatment of all investors with respect to one another. However, few investors understand the intricacies of the issue; few managers care to explain it, and over time, somehow hedge fund returns turn out to be just a little bit disappointing. This is part of the reason.

Show Me My Money

Another area where investors have been way too accommodating is position transparency. An article in the Financial Times (“Poll highlights fears on industry secrecy,” 2009) found that two thirds of investors in a poll cited either graduated fees or increased transparency as necessary inducements for them to invest. You’d think that for 2 & 20 you’d be entitled to see where your money is. But hedge fund managers have been so effective at convincing investors they don’t want to look under the hood that I’ve heard investors note approvingly the restricted transparency a manager provides. Some of the arguments make sense. There’s always the risk that even if the detailed position information is only shared with existing investors under signed confidentiality agreements it’ll somehow leak out. A manager with a short position in a stock that becomes widely known risks others buying long positions or covering their own shorts anticipating that the manager will have to cover at a loss. This would of course hurt all the investors in the fund, and so withholding information protects the investors. The same can be true where a manager is in the middle of establishing a large position in a security and wants to maintain a low profile until it’s complete.

But in far more cases it’s because the manager wants to obscure the actual sources of profitability. This can be to preserve some intellectual edge or proprietary trading model whose insights might be revealed along with the positions, or to make it harder for investors to precisely analyze what risks are being taken and therefore the quality of the returns. In fact the hedge fund industry provides less information to its clients than any other area of asset management. Institutional asset management of equities and fixed income has long operated through separately managed accounts which allow the client to see precisely where there money is as well as ensuring they only pay their own costs (unlike the earlier example of ACI).

Away from traditional asset management, alternative asset managers such as private equity and real estate routinely disclose the names of the companies or real estate projects in which they’ve invested. But hedge fund managers have been able to buck the trend. One enormous benefit to the industry has been the relatively little quantitative analysis that investors can do on their own to assess how they’re making money and if they’re making enough to justify the risks they’re taking. The opaque nature of the hedge fund investment means that it’s often impossible to see what actual risks are being taken. The best an investor can do is compare returns after the fact with how markets moved and then make assumptions about whether those same relationships will hold. As a result, hedge funds have been able to market themselves as delivering uncorrelated returns and investors have had little to go on beyond the returns themselves. Since portfolio theory and common sense will make an uncorrelated investment more desirable, the limited information provided by hedge funds has played to this directly and with great effect. In fact, one very large and successful hedge fund placed constraints on how much information an investor could share even within its own research department.

In one case, a particularly secretive hedge fund insisted that only a select group of individuals at a fund of funds investor was to review the reports the manager provided. This investor was even required to implement changes to its database software so as to comply with these demands. Non-compliance was to risk being fired as a client, illustrating the lopsided relationship that has long existed between the industry and its paymasters. But significant risks are being taken by hedge funds, as shown so spectacularly in 2008. While hedge funds clearly didn’t cause the crisis, they performed substantially worse than they should have and in many cases imposed restrictions on investor withdrawals to support their own business survival as much as to protect their investors from dumping holdings at a large loss.

Traditional asset management measures returns compared with a benchmark. Information Ratio compares the excess return a manager earns over a target benchmark with the standard deviation of the excess return, and as long as the benchmark is relevant will differentiate between good and weak performance per unit of risk. In addition, precise knowledge of the positions held allows factor analysis to examine subtle risks (such as an overweight toward interest rate sensitive stocks or consumer demand). Meanwhile hedge fund analysis has remained a mostly qualitative business. Sharpe ratio is often used, but it was designed for use with stocks as part of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and most academic literature notes that it’s not much use on hedge funds which don’t behave like stocks because they’re not stocks. Most of the number crunching that hedge fund allocators do uses historic returns because that’s all they have. While transparency has clearly improved since 2008 through greater demands from investors, it still falls far short of what they receive elsewhere. The entire industry from consultants to pension funds has largely accepted the more limited information they currently receive, which perhaps helps explain the weak results they’ve earned in aggregate.

A good friend of mine, Andrew Weisman, once wrote a wonderfully provocative paper called “Informationless Investing and Hedge Fund Performance Bias.” It’s a fascinating thought experiment that illustrates why you need to know where your money is. In Andy’s paper he describes a trading model whose returns are simulated through a Monte Carlo simulation. In other words, he calculates the results his trading model would generate over thousands of possible outcomes where the mathematical relationships amongst stocks, bonds, and so on are similar to history. This is a commonly used technique to value complex securities. The paper then plots the returns on the trading model as if it was a hedge fund, and the resulting chart looks like every investor’s dream. A very stable but attractively high return with apparently little relationship with stocks, bonds, or anything else an investor might have in his portfolio. It naturally has a high Sharpe ratio and if it existed every investor would want an allocation.

Incidentally, Bernie Madoff’s fund looked very like Andy’s model, which should have been a clue to more people than Harry Markopolos (whose book, No One Would Listen: A True Financial Thriller detailed his conclusion that Madoff was a fraud based partly on his returns). But the Informationless Investing model is simply selling options. It sells out-of-the-money put and call options on a regular basis, incurring limited risk to short-term moves in the market but exposing itself to ultimate bankruptcy. The simulation illustrates that the strategy will probably “blow up”, or lose a third of its capital, within seven years (that is, the probability of it not blowing up drops below 50 percent at the seventh year). And of course few would choose to be simply short options, although the returns do look very attractive for a time. In fact, as Andy notes, the average expected life of the model (or the time until it will probably destroy itself) is longer than the life of the average hedge fund. While easily dismissed as a theoretical exercise, there have been cases in which a fund shorted options during the month only to cover the positions just before month end when investors were provided “position transparency.”

Informationless Investing describes two other theoretical trading techniques that can produce attractive returns but either understate the level of risk being taken or ultimately lose substantial capital (or both). Although the paper was originally published in 2002, its insights are timeless and every hedge fund investor would be well served to ponder its implications.

Receiving comprehensive details on the positions held by one’s hedge funds would seem to be both a reasonable request and also a sound way to see exactly what is going on under the hood. While disclosure has improved in response to investor pressure, current practice still falls short of complete openness. It’s sometimes argued that if provided with every last detail through a daily computer download, many investors would be simply overwhelmed and unable to process the complex data received so as to obtain useful information from which they’d have a better understanding of their investments. There’s certainly some truth to this as well. Our own experience with seeding managers can illustrate this; as we began receiving daily position downloads from our new, small managers we encountered all kinds of problems getting the data in the right format. Things like this can be incredibly mundane but time consuming at the same time. The software that we used to crunch data on each fund’s positions needed to receive the data in a certain format, while the manager might be using a different system (perhaps provided by his prime broker).

Figuring out where the errors were and correcting them could easily distract from more important tasks for both the manager and us, and in fixing it we certainly learnt more about data mapping than we ever wanted to. Then there’s the question of what you do with all the data once it’s been processed. Looking at the overall risks for a portfolio of hedge funds that straddle multiple strategies may require combining risks from, say, a global macro fund trading currencies with a convertible arbitrage fund. It’s not really clear that combining them gains you any more insight than looking at each separately given how unrelated their strategies are, and we soon concluded that transparency was best used on a manager-by-manager basis so as to deepen our understanding of what was going on. Not having complete access to exactly what you own creates additional risks.

Summary

Understanding what any individual hedge fund has done can be surprisingly complicated once you decide to dig into the details. The industry has long provided far less information to its clients than any other asset class, and while transparency has improved, investors remain surprisingly quiescent. As seed investors receiving daily reports on trades completed, we were able to improve our understanding of the investments we were in and see whether we were receiving fair treatment or not. It can be hard, painstaking work making sense of several months’ worth of transactions and the resulting questions may not all be comfortable ones. In some cases being presented with a comprehensive record of activity may well feel like you’re holding a firehose not a glass, and many complex trading strategies would likely be incomprehensible if viewed without the manager as a guide. In some respects less than complete transparency suits both; investors needn’t struggle with intricate and subtle trading strategies, while managers preserve some secrecy and perhaps mystery around their returns. In addition, if the fund suddenly suffers large losses, the investor wasn’t at least in theory armed with enough information to have anticipated it, reducing the legal risk it may face for having remained in the fund. The ultimate result is that of a very unequal partnership, in which the manager retains the upper hand. Investors are partners in a purely legal sense, but the relationship can sometimes feel like something very different.