Chapter 9

Why Less Can Be More with Hedge Funds

Broadly speaking across the breadth and history of the hedge fund industry, investors have not fared that well. The amazing result is that if all the money ever invested had instead gone into Treasury bills, the investors would have been better off. Few outsiders initially believe it when first presented with this fact. Yet I’ve spoken with people who’ve dedicated most of their careers to the hedge fund industry and they are rarely surprised. This gulf in perceptions between the hedge fund industry and everyone else is a stunning indictment. Poor timing, weak analysis, and hefty fees have all contributed to this outcome.

Of course, saying that hedge fund investors in aggregate have done poorly isn’t the same as saying everybody’s lost money. This book shouldn’t be interpreted as making that assertion, because it’s plainly not true. Just as the average income tells you little about the range of incomes in a country, so it is with investing. However, most of us have assumed that the average in this case was pretty good, whereas it turns out to be pretty poor. But even though there are hedge fund investors who have done very well as clients, it’s surprisingly difficult to identify them. I’ve looked for clients who have made substantial profits as clients, excluding any fees they’ve earned from others’ money. This excludes George Soros, for example, whose fortune clearly began with fees earned from managing money. Over time as his wealth grew he became a substantial investor in his own hedge fund and no doubt his current wealth has been augmented by trading profits—but he clearly wouldn’t have reached his current state without the “2 and 20” combination of management fee and incentive fee. Steve Cohen of SAC is famous for being such a talented trader that he was able to take fully 50 percent of the profits he earned for clients as his incentive fee and still generate consistently high returns. He, of course, eventually made so much money from this arrangement that an increasing portion of the money he was managing was his own, and clients became an unnecessary distraction. Eventually he gave back pretty much all the clients’ money, preferring to focus just on managing his own.

Of course George Soros and Steve Cohen are examples of highly successful hedge fund investors. They’ve made substantial sums managing their own money as well as charging fees to manage others’ money. Nevertheless, if they are the best examples of profitable hedge fund clients, then the industry looks increasingly as if it exists to serve itself. In that case, the purpose of hedge funds is to provide jobs and wealth creation for the industry professionals: managers, consultants, allocators, prime brokers, and other service providers. Can any commercial industry thrive, or even survive, if its clients aren’t the fundamental reason for its existence, the purpose behind all this activity? In fact the long-lasting and spectacular growth of hedge funds in itself seems to refute the notion that they haven’t added any value. In a capitalist system the market decides winners and losers, and since there are clearly so many providers of hedge funds that are winners, their continued presence can only be because they’re providing something worth more than what they charge for it. It’s possible we’re measuring the wrong things in trying to establish value received by clients. Maybe investment profits in themselves aren’t the sole yardstick.

There Are Still Winners

There are plenty of investors that are happy with their hedge fund investments. Since the individuals that are clients have to be wealthy enough to be “accredited investors,” they’re not that easily tracked down. Very rich people maintain discretion about their financial affairs. But some institutional clients do disclose their results. University endowments such as Yale and Princeton (Sorkin, 2010), and public pension plans such as the California Public Employee Retirement System (CalPERS) have noted generally satisfactory results. And I have a number of friends solidly in the “high net worth” category who say their hedge fund investments have been very satisfactory. But for every $1 well invested there’s another $1 that wasn’t, since the results in total aren’t good.

Hedge funds are said to provide diversification, and they certainly do. Most investors will happily accept a lower return on investments that are not highly correlated with their current portfolio, and of course there’s a whole academic theory (the Capital Asset Pricing Model [CAPM]) which can calculate how much less of a return you need from those uncorrelated investments. It depends on how related they are to what else you’ve got, how likely the new investment is to go down when everything else is going down. The less likely it is that they’ll move together, the more helpful it is to your overall portfolio, which means that they don’t need to make as much to justify the investment; but in the CAPM world, whatever you invest in has to do at least as well as Treasury bills. If even over the long term the investment doesn’t do as well as Treasury bills, then there’s no point in having it.

On the other hand, if investment profits aren’t the main reason to invest in hedge funds, it’s hard to know what is. Certainly investors give every indication that profits are what they’re after. It’s hard to think of any other non-economic objective. Hedge funds don’t really serve any other useful purpose. Of course, the Robin Hood Foundation that Paul Jones started years ago provides generous charitable support to a wide number of good causes, and while that’s to the credit of the supporters of that charity and others like it, philanthropy is a happy by-product of hedge funds, not the reason they exist.

Perhaps because there has been so much wealth created by hedge funds, establishing how well clients have done receives less scrutiny than it might. The combination of a respectable long-run average annual return, (which ignores the fact that the best years were when the industry was small) with many extremely wealthy practitioners, is a powerful reason to join in.

Why have investors done so badly out of their infatuation with hedge funds? Whose fault is it that the results have been so skewed in favor of just about everybody—except the providers of the capital from which so much has been earned? What should investors do so as to restore some balance to the relationship? Can it be fixed, or will hedge fund clients continue to bet against a two-headed coin?

Some of the most talented investors in history run hedge funds (or have retired from doing so). The compensation assures that in a capitalistic system, those with the most sought-after skill maximize their own return on selling their services. Personally, I find a great deal to admire in the thought process of George Soros, as he concluded that Sterling would be unable to maintain its peg against the Deutsche Mark in September 1992 and then backed up his belief with enough money to break the Bank of England. His $10 billion bet netted a cool $1 billion, and in an interview around that time noted that on hearing the British government nearly borrowed a further $15 billion to support their currency, “… we were amused because that was about how much we wanted to sell” (Slater, 2009). While Soros earned few plaudits in the United Kingdom at the time for “breaking the Bank of England” as the tabloids coined it, this episode confirmed his legendary status as a hedge fund manager.

Who can fail to marvel at John Paulson, as this experienced merger arbitrage manager, with little experience in credit derivatives, identified and constructed dazzlingly high pay-off trades with remarkably little risk, to profit from the inevitable collapse in the housing market? The acute risk management judgment of Alan Howard, as he guides his portfolio of traders through successive crises with an incomparably deft touch, knowing just when to reduce risk and just when to press his advantage, is almost awe-inspiring. Bruce Kovner, David Tepper, Louis Bacon, and others at the top of the industry possess fantastic abilities and have been able to implement them across large pools of capital. Hedge funds are not short of investing talent—far from it. But star-struck investors have too often equated enormous financial success amongst managers with high returns for clients (though I should note that all the managers listed above are among the Top 10 most profitable for investors, according to research by Rick Sopher of Edmond de Rothschild Group and reported in the Financial Times September 10, 2010). When I first moved to the United States in 1982 I noticed a subtle difference in attitudes toward wealth between Europeans and Americans. In Britain, an accountant/doctor/lawyer parking his S-Class Mercedes would cause onlookers to comment disapprovingly at how he must be ripping off his clients in order to afford such a car. In America, the same scene would cause most to conclude that the individual must be successful and therefore worth doing business with! Although hedge funds and their investors are global, the American attitude toward wealth, to staying close to winners, has prevailed, as with so many American values, as the world has become flatter (credit Thomas Friedman, author of The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century for illustrating how values and technology are making the world smaller and flatter).

If there is such a thing as Hedge Fund IQ (HFIQ), or a quality which combines superior investment analytical ability, a trader’s instinct for survival, well-developed commercial sense, and a highly competitive winning attitude, it would have its own brutal hierarchy. Hedge fund managers would be at the top, next would come the traders at banks who trade with them and against them (the best of whom move to hedge funds or start their own), after them would come those that invest directly in hedge funds (funds of hedge funds and other institutions), below them, the consultants that advise others on their investments, and, at the bottom, the trustees and investment committee members of the large institutions who have so recently added alternatives to their portfolios. All of these levels include highly intelligent people in the conventional sense and this description of the HFIQ hierarchy should not be regarded as demeaning to those not at the top. Golf includes players of wide-ranging abilities (thankfully for me!) and you don’t have to be as good as the club pro to enjoy the game. Nor does mediocre golf ability say much about how well you play basketball. Hedge Fund IQ is a highly specialized, narrowly defined quality. Those possessing it in abundance run hedge funds, while the rest get as close as they can. You can play a round of golf with the club pro for money, but you’d better use your handicap to get fair odds. Hedge fund investors need to acknowledge they are unequal partners with their chosen managers and pursue negotiating strategies that compensate, or invest elsewhere.

If investors have done so poorly, whose fault is it? When looking at the split of profits between fees and returns and the extremely modest share of the pie retained by investors, it’s tempting to condemn hedge fund managers as representing the worst excesses of Wall Street, exploiting markets, investors, and knowledge for their own benefit. The capital markets fundamentally exist to channel savings in directions where they can be most effectively deployed. Few would argue that the efficient allocation of capital requires the creation of today’s hedge fund fortunes in order to be carried out effectively. But that philosophical question is for others. Investors are all voluntary clients. Hedge funds are meeting a clear demand from the market. And the vast majority of capital in hedge funds is provided by “qualified” investors, either individuals with sufficient net worth to be deemed “sophisticated” or institutions fully capable of accurate analysis. The fact that it hasn’t turned out well is very largely the fault of the investors themselves. Faulty or weak analysis, performance chasing, shortage of skepticism, and a desire to be associated with winners without proper regard for terms have all caused the sorry result.

Avoid the Crowds

The assertion that small, new hedge funds outperform larger ones is often debated within the industry. There is a growing amount of academic research on the topic and countless articles. The case for small managers is inspired by the fact that most of today’s successful hedge funds began life much smaller than they are now. In addition, their returns were often higher. This is why there’s such a gaping difference between overall profits earned by investors (since recent years’ returns have been disappointing) and average industry returns (strong results in the 1990s were generated by a much smaller industry).

Being a small manager has many benefits. As with any entrepreneur launching a new business, the start-up hedge fund manager throws himself body and soul into the new venture working 24 × 7 to get it off the ground. This intensity of effort is critical, because if returns are not good in the short run, then, at least for this manager, there won’t be a long run. Small amounts of capital are generally easier to trade, in that you can usually buy or sell as much of a security as you need without moving the market away.

Closed-end funds (CEFs) are a great example. These are like mutual funds, except that they have a fixed share count, so investors buy shares in the secondary market just like any other stock. Closed-end funds publish a net asset value (NAV) every day just like mutual funds, but since they don’t issue and redeem shares every day to meet/accommodate demand, the price of their shares doesn’t have to equal their NAV. In fact, the shares usually trade at a discount to NAV. Anybody who thinks the markets are efficient should check out the closed-end fund business. In the United States it’s driven by thousands of retail investors who are looking for income. Many closed-end funds respond to this by making distributions in excess of their own investment income, which really means they’re just giving you back your own money.

Trading closed-end funds is an interesting and obscure backwater of the financial markets. Liquidity is poor and, as a result, it’s difficult to deploy much capital—but for small traders or hedge funds it can be a worthwhile area to research.

Suppose a closed-end fund has $100 and it’s invested in stocks which pay a 2 percent dividend. The closed-end fund is earning 2 percent, and this is what the investors in that fund should really see as their yield (although the fund manager’s expenses will take a chunk out of that, but we’ll leave fees out for now to keep it simple). The manager knows that a 2 percent yield is not that interesting, so he makes the annual distribution $5, covering the difference with the capital in the fund. This $5 distribution results in a “distribution yield” of 5 percent and investors who confuse it for an actual yield think they are getting a good deal. I once had a conversation with a research analyst at a large Wall Street bank, and asked her why her research didn’t describe the yield in cases like this as 2 percent rather than 5 percent. Acknowledging it was wrong, she nevertheless insisted that this was how the market (i.e., retail investors who know no better) thinks of yield and so she was simply following market practice.

Investors in closed-end funds are looking for steady income. Most stocks pay dividends that vary much less than their profits because the market rewards the predictable income this creates for investors with a higher stock price. CEFs are no different, and even though their actual returns are largely driven by changes in the prices of what they own, the payment of a regular distribution or dividend attracts investors who want stable income. But whereas a company whose dividend is not covered by its profits will, before long, reduce its dividend (and one warning of this is when a dividend yield is unusually high, indicating that the market believes it’s unsustainable) CEFs work differently. Some funds, recognizing the appeal of a high yield, will make large distributions partly supported by the underlying investments. This will perversely make the fund price rise regardless of the long-term unsustainability of such a strategy, because buyers like the higher yield, even though a chunk of it comes from giving them back some of their own money. Eventually the CEF would have used up all its capital in supplementing its dividend and would be an empty shell, having returned all the money to investors. However before that happens they’ll typically cut the distribution to preserve capital which invariably sours investors on the fund and sends its price lower. Whereas a high dividend yield on a stock can be a warning, in a CEF it’s an invitation. It seems that no matter how many articles are written on the topic, investor behavior doesn’t change.

Then there’s the closed-end fund initial public offering (IPO). Everybody on Wall Street knows that you never buy a closed-end fund when it’s being issued. This is because the underwriters take 7 percent of the proceeds as a fee, so if the fund is issued at $20 it immediately loses 7 percent of its NAV and falls to $18.60. It’s a guaranteed loss, and yet, every closed-end fund IPO is evidence of the continued gullibility of certain parts of the investing public. Even the underwriters know it’s stupid—I had another conversation with the capital markets group of a Wall Street bank, where they asked me if we had looked at any recent CEF IPOs. No, I said, they’re all an easy way to lose 7 percent. This was quickly acknowledged and we moved on.

Boulder Total Return Fund (BTF) has played this game with great skill. BTF is run by a fellow called Stewart Horejsi in Colorado. His web site is intended to evoke Warren Buffett (of whom Stewart is a great admirer) and describes his long-term approach to investing, through seeking value and using low turnover. For a time BTF sported a high distribution yield—even though it was supported by returning investors’ own capital to them. Earlier this decade BTF traded close to its NAV as it made regular distributions to investors. Then, in 2008, it did what no CEF should do—and eliminated its dividend. The price duly fell and a large discount opened up between NAV and price. Some managers regard a wide discount as a vote of no confidence in their abilities and take steps to close it (perhaps by buying back shares). However Stewart Horejsi recognized an opportunity and so has been regularly buying shares in the open market for himself and trusts that he manages. He correctly saw the persistent discount as an opportunity, and reinstating the distribution would simply make it more expensive for him to continue buying the shares. Sometimes an activist investor will get involved and will buy up enough shares to justify a board seat, where he’ll threaten to force a change of management, unless steps are taken to increase shareholder value. But in the case of BTF, a substantial minority of the shares is owned by the manager and affiliated entities, so it’s virtually impossible for an activist to gain a foothold.

Another sound rule of CEF investing is that you never buy funds at a premium to its NAV. Why pay $110 for a basket of stocks that are only worth $100? If you like them that much, just buy the underlying stocks in their portfolio. Nevertheless, people do it all the time, and in doing so, lock in poor or negative returns on their investments.

A closed-end fund is really nothing more than a company that invests in other public companies. They don’t manufacture anything or provide any services; they just own stock in other companies. A CEF earns the investment returns on its holdings and passes on at least 90 percent of them to its investors. It pays fees to the money manager who oversees the portfolio. Valuing a CEF is not nearly as difficult as valuing an operating company like Microsoft or Kraft. It’s worth whatever its stockholdings are worth, and CEFs regularly publish a NAV (similar to mutual funds).

Until I began researching closed-end funds I had never come across such an inefficient market. Retail investors do dumb things every day, whether it’s participating in an IPO or buying a fund at a premium to its NAV (something you should never do). There are dozens of articles on the subject of CEFs with all kinds of sensible advice, and several books which discuss the persistent discount to NAV and why it exists. While there’s nothing easy about trading (and in my experience it usually feels easiest just prior to a loss), if you pay close attention, you can find relatively attractive trading opportunities in CEFs, caused by many of the self directed but less sophisticated retail investors who predominate. The returns can be attractive, but the liquidity is limited. For instance, BTF only has a market capitalization of around $200 million and trades around $300,000 to $400,000 in value on a typical day. Even if you were 50 percent of the average daily volume, it would still take 15 days to accumulate a position of $5 million. A moderately sized hedge fund of $500 million in assets under management (AUM) would scarcely find it worth the time to concentrate on something like that, and a larger one wouldn’t bother at all. However, for smaller hedge funds and for sophisticated individual investors (who are thankfully a minority in the CEF business) it can be worth taking the time to research and exploit some of the inefficiencies.

This is just one example of how small size can be a benefit. None of the opportunities in CEFs are large enough to be of any use to established hedge funds, but smaller funds can often find worthwhile trades.

Why Size Matters

Small hedge funds have been shown to do better than the industry as a whole. There’s plenty of academic research on the topic. A fairly comprehensive study was carried out by Rajesh Aggarwal from the Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota and Philippe Jorion from the Paul Merage School of Business at the University of California at Irvine in 2009. It was called, “The Performance of Emerging Hedge Funds and Managers.” The two authors were very thorough in taking a comprehensive database of hedge fund returns and eliminating any biases that could have overstated the results. Since hedge fund managers report their results voluntarily, it’s no surprise that a newly reporting fund has just experienced strong performance. Some databases allow managers to include the previous months’ returns that took place before they officially joined the database, in effect backfilling the database, so that it looks as if they’ve been included for longer than is the case. Aggarwal and Jorion conclude that new managers generate an additional 2.3 percent in their first two years of life, relative to later on. While this may not seem like much, the authors run statistical tests to show that it’s a fairly reliable phenomenon, and compared with average annual returns of, say, 6 percent it can be a meaningful addition.

Many investors have misinterpreted historic hedge fund returns in deciding to add an alternatives allocation to their investment mix. They’ll carry out a what-if analysis to see what their returns would have been like with a hedge fund allocation. They’ll use an index, like HFRI, to represent hedge funds in this analysis. Most portfolios can be shown to benefit from the diversification of hedge funds when one of the popular indices (such as HFRI) is used to replicate, say, a 20 percent hedge fund allocation as part of a traditional portfolio. The results of the 1990s show more benefit than using just the last few years, but then using a longer time period is often more appropriate. However, as noted elsewhere in the book, the hedge fund industry was better when it was smaller. The diversification benefit was most pronounced when the industry was much smaller. In addition, indices such as HFRI are equally weighted rather than asset weighted, so many smaller funds are disproportionately represented. Although big funds manage most of the capital, small funds make up most of the index.

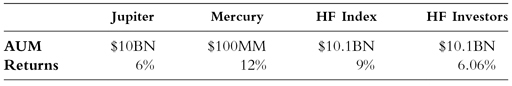

The HFRI index represents the returns of the average hedge fund, but not the portfolio of the average investor. This is a crucial difference. To use a simple example, suppose there were only two hedge funds, Jupiter and Mercury. Jupiter managed $10 billion and Mercury managed $100 million.

The return of the index was 9 percent, the simple average of the two funds. But most of the money is in Jupiter and so Jupiter’s returns dominate the overall returns earned by investors. If Jupiter had generated better performance than Mercury, then investors as a whole would have done better than the index. Using average returns to analyze the industry is perfectly acceptable if Jupiter is just as likely to do better than Mercury as not. But here is the crucial point: Mercury, and all the other small hedge funds out there, do on average tend to outperform big, lumbering Jupiter. Small hedge funds have outperformed big ones, and ignoring this fact has led many investors down the wrong road. The reason the average investor hasn’t made money in hedge funds, while the average hedge fund has made money, is because the average hedge fund is small, and the industry itself was small when the higher returns were being generated. Investors have been marching steadily toward the mirage of yesterday’s returns. As the crowd of investors seeking those returns grows, the size of the group ensures that they won’t be achievable. Size has long been the enemy of hedge fund returns, and the greater the sums plowed into the industry the more assured you can be that the outcome will be disappointing.

Most of the flows into hedge funds are directed toward the larger managers, both on the basis that they are safer, but also because they have the capacity to absorb relatively large institutional allocations. This seems like a fundamental disconnect between the analysis and the implementation. Clients are basing their strategic allocation decision on one set of information, but are then implementing that allocation in a way that’s critically inconsistent with their earlier analysis. They’re investing in a way that doesn’t reflect the history of the index on which the decision was based. Small hedge funds got them interested, but large funds are where they go.

In some respects, it’s quite an amazing selective use of history. Investment products are routinely labeled with the warning that “Past performance is no guarantee of future returns.” Like most warnings, it’s not really helpful. It might as well be “Remember, you could lose money.” Well, of course. But investors do look at past returns in analyzing hedge funds, and even though most will say they don’t invest purely on the basis of historic returns, for some reason, high performance tends to attract capital. Although, in the equity and debt markets, there are “value” investors who look for unloved stocks or distressed debt and seek to take contrarian positions, I’ve never come across a contrarian hedge fund investor. I’ve met plenty of hedge fund managers who have argued that their own recent poor performance renders them an even better investment right now (and sometimes that was true) but I’ve never run into an investor whose strategy was to seek out distressed hedge funds. In the final analysis, investors do look at past performance in deciding where to allocate their capital and not surprisingly strong results get their attention. Hedge fund clients are, without doubt, momentum investors. They invest in what’s worked in the past with the conviction that it will continue working in the future.

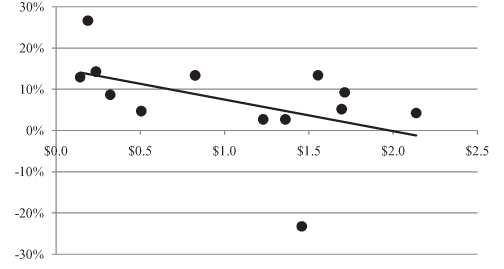

Nonetheless, while investors have relied on past performance of the hedge fund industry (or of the average hedge fund) to make portfolio allocations to hedge funds, they haven’t taken into account the effect of industry size. In statistical terms they’ve assumed positive serial correlation. Serial correlation measures how likely it is that one number in a series will affect the next one. There are many examples in finance and economics—many economic statistics tend to continue in one direction for a while, before turning. Housing activity was consistently positive until 2007 and 2008, when the market crashed. New housing starts used to run at around a 1.5 million annual rate, whereas now they are around a third of that. Housing starts were serially correlated on the way up, and unfortunately on the way down. The same was true of house prices during this time. Even though hedge fund returns have been trending down, the averages have remained positive. However, there is also a relationship between size of the industry and performance. Figure 9.1 is a scatter plot that compares size with the excess return over T-bills generated by the industry each year.

Even just looking at the chart, it’s clear that there’s a relationship between size and returns. Returns were higher when the industry was smaller. The correlation is −0.42, showing that returns are negatively correlated with size. What’s true for individual hedge funds is true for the industry as a whole. Just as small hedge funds do better, so did a smaller hedge fund industry.

It’s an easy mistake to make, but one that is pretty fundamental. The research on whether early stage hedge funds outperform their more established peers tends to show that they do, though some of it is inconclusive. However, the research does indicate that small, nimble, hungry managers do better. The academic paper by Aggarwal and Jorion, mentioned earlier, is probably the most thorough on the topic and their conclusion is that small is better. Nevertheless, what does seem abundantly clear is that the industry as a whole had its best years when it was small. This was no accident; it was precisely because the benefits to small size were predominant. The steady deterioration in relative returns of hedge funds, compared with traditional assets such as equities and fixed income, is surely the most compelling evidence that size hurts returns. Investors have largely been seduced, by the apparent safety of large and successful hedge funds, into thinking they can enjoy the attractive uncorrelated returns of a bygone era, while enjoying today’s industrial-strength risk management, infrastructure, and reporting. It just hasn’t worked. The risks have been higher overall than expected, and the returns have been lower. The blame for this must lie squarely with the investors themselves, and the advisers/consultants on whom they rely. Hedge fund managers rarely tell you why you should invest in hedge funds; they simply make the case for their hedge fund. Meanwhile, the consultants and funds of hedge funds have been the avid proponents of allocating to a diverse pool of managers and the consequent heavy bias toward the largest funds. And why not? If your business model is based on earning a fee on AUM, scalability is critical. Recommending lots of small investments in small hedge funds isn’t a good business model, because it takes a lot more work to get the money invested.

This is where investors have allowed themselves to be badly misled. Historic industry performance reflects the average hedge fund. The average fund is small. The 80/20 rule applies to hedge funds as with so many things. The indices, particularly if you go back a few years, reflect a different composition of funds than is available today. Funds were smaller and, as a result, many strategies were available that simply don’t scale with the size of today’s industry. The success of the past has led to a secular change. The biggest hedge funds are large institutional asset-management companies, with all the infrastructure, processes, and research capabilities of more traditional firms. But that’s not how the hedge fund industry grew. It’s a consequence of its growth.

Many investors, and based on the data it might well be the majority, have failed to incorporate this into their analysis. Investing in hedge funds in the 1990s was risky back then. I know, because I was doing it. Simply finding some of the best managers relied on word of mouth referrals. There was no database that you could rely on to run a screen of funds in a particular strategy. Of course, there was little regulation and a real sense that you, the investor, were in the Wild West. These were uncharted waters, where we were discovering managers who were already highly successful, but still not widely known, because the hedge fund business itself was still so small. Back in the mid 1990s when I was helping JPMorgan find hedge funds, we often found ourselves visiting small firms with only a handful of investment staff in unassuming offices. The principals were certainly not well known to the financial media and they were operating far out of the spotlight. They weren’t to be found speaking at industry conferences, and were often referred to us by some other knowledgeable investor, who was also in the hunt for unknown talent. In fact, hedge fund investing back then embraced unconventional strategies. We wanted someone with a secret sauce that while proven was not yet widely known or imitated.

A great deal of the due diligence process relied on a series of interviews with the manager trying to unlock the investment process he was using. Positions might be disclosed, but a regular data feed of daily trades was not expected. At the time, it did seem risky, but the potential returns justified it. Many talented traders had already left big firms to set up their own businesses, where they could operate with relative freedom and make some serious money.

Many of today’s investors have assumed a link between yesterday’s hedge fund performance and today’s available managers. They take aggregate performance of the average fund, generated during a time of far less competition, and then invest in hedge funds that represent today’s industry but not yesterday’s. Investors want yesterday’s returns without yesterday’s risk. As Winston Churchill said on hearing that Britain and France had agreed to allow Germany to annex Czechoslovakia in the forlorn hope it might appease Hitler and avoid World War II, “They had to choose between war and dishonor. They chose dishonor. They will get war.” Of course, the stakes are smaller. The downside is hardly global domination by an evil madman. Nevertheless, the point is that today’s investors are ignoring the key features of the historic returns that have drawn them into hedge funds in the first place. They believe they can choose between having yesterday’s returns with today’s (more understandable) risks. To do this, they’re investing in hedge funds that look nothing like those whose aggregate performance has drawn them in to this point. They’re going with large, established hedge funds in order to eliminate many of the infrastructure, accounting, and operational risks a smaller, less well-financed business might face. By eliminating yesterday’s risks, they’re also eliminating yesterday’s returns.

There’s another important point that’s worth making. Manager selection plays a vitally important role in an investor’s results. Institutional clients routinely make strategic allocations to traditional assets such as public equities and fixed income without needing to consider whether poor individual security selection will overwhelm their returns. An investor who believes active management doesn’t add value to an equity portfolio can still justify investing in equities passively, through an index fund. Earning the market return can be quite acceptable.

But for a hedge fund investor, the market return has been disappointing to say the least. The only way to successfully invest in hedge funds is to be above average at manager selection. If you can’t pick managers better than the average investor, hedge funds are not a wise choice. The hedge fund industry has benefitted because most investors think they are better than average, just as most drivers do. Many hedge fund investors live in Lake Wobegon, Garrison Keillor’s fictional town in Minnesota where, “… all the children are above average …”

In order to get what they want out of the hedge fund industry, investors need to take a different approach. They need to acknowledge the important role that size plays, both at the individual manager level as well as for the industry as a whole. They need to be far less comfortable investing with the crowd than is currently the case. It seems as if every day another pension fund announces that it’s planning to increase its allocation to hedge funds, so as to reach the return target it’s set itself to fund its obligations to retirees. It’s no longer a contentious decision, and no doubt an increasing number of pension fund trustees are feeling pressure to embrace the conventional wisdom. But if it’s fine to base such decisions on the historic record of the average hedge fund (which is quite respectable) then surely the historic record of the industry is an equally important consideration? If you’re going to invest based on looking backward, look backward at all the information, not just selectively. Every time an institutional investor makes a decision to allocate to hedge funds, they should make clear just how they intend to confront the headwind that the industry’s continued growth represents.

There is some reason to believe investors are shifting gears somewhat. Deutsche Bank released the results of a survey (reported in the Financial Times, March 2011) in which 65 percent of respondents expected to allocate some capital to funds with less than $1 billion in AUM, and 62 percent expected to bypass funds of hedge funds (FOHF) completely and do all their investing directly. The fees that funds of hedge funds charge on top of the hedge fund fees themselves can eat into returns, although the biggest FOHFs have substantially greater research capability than even the largest pension funds. However, the survey also found that respondents expected the industry to attract $210 billion in new inflows, which would make it challenging to direct a substantial portion to smaller managers.

Where Will They Invest All This Money?

Many investors avoid being more than a certain percentage of a hedge funds’ AUM, which limits how much they can invest with any one manager and may require a large number of different funds to accommodate their capital. Due diligence is a time-consuming business and, for this reason, strong growth in the industry is likely to continue benefitting the biggest. The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) is estimated to have $600 to $800 billion under management. An article in Hedge Funds Review by Madison Marriage in May 2011 noted that it’s not worth their time to invest less than $100 million, which means if they want to remain less than 25 percent of a fund’s assets, the fund itself needs to have at least $400 million.

ADIA is a notoriously demanding client as well. In my own experience at JPMorgan, just scheduling a meeting with them was a laborious process and they think nothing of changing the schedule at the last minute, or asking you to fly in from another continent at short notice. Being big can have its benefits.

Meanwhile, public pension plans continue to plow substantial sums into hedge funds. Many have overall return targets of 7 percent or higher for the assets they are managing on behalf of millions of future retirees. With interest rates in developed countries so low and returns from equities over the last 10 years disappointing, the case for adding an allocation to hedge funds as a way to meet future obligations is compelling. Preqin is a research firm that studies what these and other large investors do in the hedge fund arena. In March 2011 they released a survey covering more than 300 of the world’s biggest public pension plans and similar pools of retirement savings. This group has been steadily increasing its hedge fund allocations to where they are currently 6.6 percent of total assets. They were unswayed by the 2008 crisis and related volatility, as befits a group of very long-term investors. And the returns they expect to make from hedge funds appear quite modest—around 6 percent.

However, Preqin’s report goes on to note that the median pension plan surveyed has missed even this objective by more than 2 percent over the last five years, and over the last three years their returns are negative. In July 2011 the Financial Times reported on its own research and found that large North American pension funds were doing substantially worse with their hedge fund investments that the industry averages. (McCrum, 2011) They noted a study by academics at Yale University and Maastricht comparing the 1.9 percent earned by U.S. pension plans with the 5 percent return on the Hedge Fund Research Index from 2000 to 2008. Canadian pension plans had experienced similar results.

Moreover, even a 6 percent return may be challenging at the industry’s current size. In round numbers, the hedge fund industry has $2 trillion in AUM. Risk-free rates on U.S. Treasury bonds are anywhere from 0 to 1.5 percent depending on maturity, so let’s assume 1 percent is the risk-free rate. The 6 percent return assumption from hedge funds translates into a 5 percent return over the risk-free rate, or about $100 billion in annual profits on $2 trillion in AUM. The problem is, hedge funds only made this much money once in history, and that was in 2009 when they generated $200 billion. Of course that was the bounceback from 2008 when they lost almost $450 billion (based on the table of estimated profits in Chapter 4) so they lost $250 billion over two years. In order to meet the objectives of their growing client base, hedge funds need to do better than they’ve ever done and they need to do it every year. As more investors jump on the train before it leaves the station, their growing weight will prevent it from traveling with much speed.

If investors can incorporate some greater skepticism about what returns they can really achieve, they’ll be better equipped to invest in less-travelled areas and to negotiate more attractive terms. Based on the history and the available research, it seems pretty compelling that you need to invest in small hedge funds. It’s small hedge funds and a small hedge fund industry that have generated the returns. If you’re going to invest based on looking back at history, invest in something that looks like the history you’re looking back at. Trustees of pension funds, and others in a fiduciary role, should be far more skeptical of the consultants that show how their investment goals will be more attainable. In fact, in researching this book, I was struck by how virtually all the books on hedge funds are proponents in one form or another. For the non-finance professional, the weight of peer group pressure and positive media must make it very hard to question what is becoming conventional wisdom—namely that every institution should have an allocation to hedge funds.

Part of the problem is that the people best situated to point out some of the industry’s weaknesses are making their living from it. Writing a book that terms hedge funds a mirage is not a smart career move for most people. And the closer you are to hedge funds the less reason there is to be a cynic, at least overtly.

Small hedge funds are more risky. They might be investing in less liquid stocks, have a less developed investment process, less robust infrastructure, fewer clients, and be in need of asset growth just to stay in business; but they’ll also be more amenable to providing clients better terms. A large investor negotiating with a small hedge fund might obtain a separately managed account, which assures the client retains legal ownership of the assets and pretty much eliminates the risk of fraud. Even if that’s not possible, the investor can demand complete daily position transparency, delivered directly from the custodian or prime broker (something we routinely did at JPMorgan, when seeding new hedge funds). The investor can probably negotiate more attractive fees, perhaps improved liquidity terms, and maybe even a stake in the business if they’re one of the early investors and want to become a seed investor. All of these features play a part, both in reducing the risk of the smaller hedge fund to the investor as well as improving the potential return. Additionally, in the case of a seed investor, if the fund does turn out to be a winner, the ownership of the business can turn out to be more lucrative than the investment in the fund.

Summary

Hedge funds will continue to attract the most talented investment managers and traders. There’s nothing else that’s close to providing the opportunity for serious wealth creation. If the best managers are running hedge funds, accessing the best will require being a hedge fund client. There’s no other way. But investors who can recognize what made the industry so successful—and acknowledge where their goals are inconsistent with what the industry can provide—will demand better terms, transparency, liquidity, fees, and information. They’ll redress the current huge imbalance that exists between the industry and its clients. By investing in hedge funds that look more like yesterday’s they are likely to find the household names of tomorrow and get a fairer deal for themselves as well.