CHAPTER 4

CHANGE YOUR MIND

Samantha feels like she has two opposing forces living inside her head.

I was driving home from work when I saw a billboard with a picture of a gigantic ice cream cone. It had chocolate ice cream dripping down the sides of a huge sugar cone. I think it was actually an ad for an air conditioner repair company but it didn’t matter. I wanted ice cream now! My restrictive voice and binge voice argued with each other the rest of the way home.

“You can’t have ice cream. It’s bad! The last time you had a bowl, you ended up eating the whole carton.”

“But I waaaaaaaaaaant ice cream! Pleeeeeeease?”

My restrictive voice won that round. When I got home, I had a bowl of cottage cheese and peaches instead of ice cream. Round two started almost immediately.

“Good job! You saved about 100 calories!”

“I know. That means I can have a string cheese.”

“At least that’s a healthier choice than ice cream. But only one.”

“Yum. That was really good but it was so small. I’m worried I’ll get hungry again in a little bit. I think I better have another one.”

“Great! Now you’ve eaten 100 more calories. You might as well have eaten ice cream instead.”

“Thanks, I think I will. It’ll be worth the extra 30 minutes I’ll have to spend at the gym.”

“One bowl? How many servings was that really? It would probably take at least an hour to burn it off.”

“Shut up. It wasn’t that much. In fact, I’m going to have another bowl.”

“What is wrong with you? You just started the diet this morning. I think you’ve broken your record for the shortest diet.”

“I’m going to start it tomorrow instead. I better finish off this carton of ice cream so I won’t be tempted by it again.”

Samantha has a constant stream of thoughts about eating—and not eating. This is head hunger—thoughts about eating even when your body doesn’t need food.

WHEN DO I WANT TO EAT?

Head Hunger

Head Hunger

Here are some examples of head hunger:

Maybe a little chocolate will pick me up.

I hate to waste perfectly good food.

Mmmm, that looks so good.

I already blew it—I may as well eat the rest.

I better have one now before they’re all gone.

I’ll just eat these last few bites; it’s not enough to save anyway.

I better eat now since I don’t know when I’ll get another chance.

I’ll get started right after I have a little snack.

I worked so hard. I deserve it.

I can hide the wrapper and no one will know.

I’m not even going to ask myself if I’m hungry. I just want to eat!

These are thoughts. Hunger is physical. Head hunger often arises automatically and habitually in response to triggers. Triggers for eating are like Pavlov’s bell. Ivan Pavlov was that famous scientist who rang a bell every time he fed the dogs in his experiment. After a while, the dogs would salivate whenever he rang the bell—even if he didn’t feed them. If you pair eating with certain activities, people, places, events, or situations repeatedly, those cues will eventually trigger the urge to eat or continue eating, whether you’re hungry or not.

You may have hundreds of triggers but the difference between humans and dogs is the ability to recognize the connection between triggers and the desire to eat.

What is a Trigger?

Think about the word trigger. In behavioral terms, a trigger is anything that serves as a stimulus that initiates a reaction or series of reactions. This concept is similar to a mechanical trigger, defined as “a mechanism that activates a sequence.”

Thinking about a trigger in mechanical terms is helpful because it takes the emotion out of it for a moment. More important, it reminds us that a trigger has no effect on its own and must be activated in some way. Similarly, your triggers for overeating are powerless over you—until the sequence is activated. Let’s explore that sequence further.

How Thoughts Become Habits

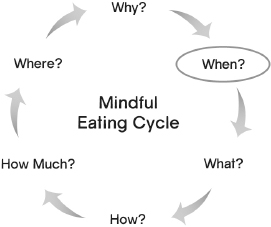

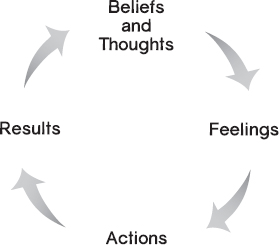

As we explore the triggers for head hunger, it’s essential to realize that what you think causes you to feel a certain way. That, in turn, causes you to do certain things that ultimately lead to specific results. It is a chain reaction that we call TFAR—your Thoughts lead to your Feelings, which lead to your Actions, which lead to your Results, and this reinforces your initial thoughts. In other words, your thoughts become self-fulfilling prophecies. This is how thoughts become beliefs. Beliefs then become automatic thoughts that drive your behaviors—in other words, habits.

For example, if your thought is, “I’ll never get all this done!” you’ll probably feel overwhelmed and hopeless. If your habit is to try to make yourself feel better by eating, you’ll shift your attention to food instead of figuring out what to do next. You’ll get further behind and think, “See. I knew I’d never get all of it done!”

It’s common for people to try to change the actions and results they don’t like without first recognizing and dealing with the beliefs, thoughts, and feelings that led to those unwanted actions and results in the first place. In the preceding example, going on a diet would address your eating (the action), but not the beliefs, thoughts, and feelings that caused it. When the thought, “I’ll never get all this done” causes you to feel overwhelmed again, you’ll struggle to stay on the diet.

You Are Not Powerless

You have the power to change the thoughts that aren’t working for you—or let them go altogether. In the example above, you could choose to think, “There’s a lot to do. I can do only one thing at a time, so I must decide what’s most important.” In place of feeling overwhelmed and looking for a snack, you’ll feel in charge. You’ll decide what to do first, then what to do after that. You may or may not get everything done, but you’ll know you did what you could.

Granted, it’s not always easy to recognize when a thought is driving unwanted results, especially if you’ve been thinking a particular way for a long time. Thinking thoughts that lead to undesirable results is a habit—a habit that can be changed through mindfulness.

MINDFULNESS

Mindfulness is awareness of what is happening in the present moment—including awareness of thoughts—without any attachment to whatever you notice. Stop reading for one minute and write down or at least notice every single thought that comes to mind—don’t filter them or judge them, just pay attention to them.

What did you discover? Were you surprised by all of the thoughts that popped into your head? Your mind never stops thinking, because that is its job! Some thoughts are triggered by cues in the environment, some thoughts are triggered by other thoughts, while some thoughts are completely random.

Many people react mindlessly to their thoughts. In other words, they re-act—repeating past actions again and again—feeling powerless to change. For many people, eating is a mindless reaction to their unrecognized or unexamined thoughts. However, your thoughts are just thoughts. Thinking a thought doesn’t make it true or important, or require you to act on it. In fact, a thought doesn’t even need to provoke a specific feeling. By increasing your awareness of your thoughts, you can begin to break old automatic or habitual chain reactions between your triggers, thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Mindfulness is helpful because it creates space between thoughts and actions. For example, in chapter 2, you learned that whenever you notice that you feel like eating, pause, and ask the question, “Am I hungry?” When you pause, you can observe your thoughts and choose how you will respond instead of reacting mindlessly. Mindfulness gives you response-ability. In chapter 3, you learned that when you feel like eating and notice that you aren’t hungry, you have three options: eat anyway, redirect your attention, or meet your true needs. At this point in the process, you may find that you’re still choosing to eat in response to “head hunger.” But at least you are consciously making a choice rather than reacting. That is progress!

MINDFUL MOMENT: The moment that you notice that you were mindless, you are mindful.

THE GREY AREA

WATCHING THOUGHTS

Mindfulness teaches you to watch your thoughts without attaching to them, judging them, or taking any action on them. Unlike the strategy of redirecting your attention—which means distracting yourself from your triggers, thoughts, and feelings—mindfulness is watching your thoughts with the recognition that they don’t have any power over you. Mindfulness puts you in charge of your mind.

In chapter 2 you learned about the Body-Mind-Heart Scan. (This would be a great time to review that important strategy.) At that point, your focus was on physical awareness—your body and your awareness of hunger. Now expand your focus to include awareness of your thoughts—your mind. It’s as if you are simply observing your mind like a scientist, describing your thoughts in concrete terms without judgment, analyzing, problem solving, or following the thoughts into the past or future. While that sounds simple enough, it can be challenging at first. Fortunately, it becomes more natural with practice. Here are several techniques you can try.

Observing

It is helpful to observe your thoughts as if they exist outside of your body. These ideas may help you visualize your thoughts as separate from you:

•Attached to balloons that float away;

•Floating by, like leaves on a stream;

•Drifting overhead, like clouds;

•Scrolling by, like the news updates at the bottom of a television screen;

•Wandering in the front door of a white room, then out the back door.

Describing

It is sometimes helpful to sort thoughts into categories and label them—without judgment. For example, label thoughts with a descriptive phrase such as:

That’s the past.

That’s the future.

That’s a judgment.

That’s not true.

That’s the future.

That’s a judgment.

That’s not true.

By gently identifying a thought in this way without trying to analyze it, you’re able to let the thought simply exist without doing anything with it. This allows the thought to pass, soon to be replaced with a new thought. If it pops up again, just notice it and allow it to pass again.

Story Time

You may find your mind wandering then realize that you’re following a storyline. It’s normal for your mind to wander; there’s no need to judge yourself for that. In fact, it is mindful to become aware that you’re not aware! When you notice your mind wandering, you could label it as “Story time!” or “Going to the movies” and say, “Of course! That’s what minds do.” Then refocus on your breathing and tune in to the present moment again.

Beginner’s Mind

Beginner’s mind is a way of looking at a situation, person (including yourself), place, thing, or thought, as if it were the first time you ever experienced, met, saw, or thought it. By eliminating the context of historical data, this perspective frees you from preconceived beliefs, and allows you to notice with objectivity.

To use beginner’s mind in the context of the Body-Mind-Heart Scan, notice with curiosity and without judgment. Make observations as a simple, “That’s interesting.” Make a mental note of whatever you noticed and move on to the next observation.

Mindfulness has helped Samantha feel more in charge of her thoughts so she can pay more attention to her life in the present. Samantha described her revelation.

It’s like I’m watching my thoughts go by on a conveyer belt. I can pick out what is actually important and let the garbage move on. Just because I think about food, doesn’t mean I have to do anything about it. I don’t judge myself for having food thoughts; I just notice them and let them roll past. When I see one of my “food battles” approaching, I give myself a little credit for spotting it, then I center myself with a few deep breaths. It feels so great to know that I have the wisdom to choose what I will think about instead of reacting to my random thoughts and feelings. It is so much more peaceful inside my head!

INTERNAL DIALOGUE

Watching thoughts and choosing which ones to pay attention to is a powerful way to interrupt an automatic sequence of events. However, it can be challenging at first because people who struggle with binge eating may be in the habit of judging their thoughts, leading to an emotionally charged internal dialogue. It may seem like there’s an angel sitting on one shoulder and a devil sitting on the other. They whisper in your ears like an old cartoon: good versus evil.

Samantha found it helpful to develop these voices as characters in her mind.

My binge voice convinces me to do things that make me feel terrible, then tells me how terrible I am for doing them. “Ice cream will make you feel better right now! Eat as much as you want. It will drown out the world. You can’t stick with anything hard anyway. You might as well eat the whole thing. You’ve blown it again! You are such a loser! What a fat, ugly worthless failure you are! Who cares anyway?”

My restrictive voice expects me to be perfect and makes me think that being perfect is the only way I can be happy. “You can’t trust yourself with ice cream. One bite and it’s all over. I know it’s hard but it’s worth it. You’ll be slim and beautiful and have a perfect life. Trust me.”

As you learned in chapter 1, this dichotomous thinking is extreme: all or nothing, right or wrong, good or bad, always or never. This can lead to stress and emotional pain and drive the eat-repent-repeat cycle. Samantha now recognizes the pattern.

My restrictive voice means well. She thinks she’s being good by following all the rules, but it’s exhausting. Then when I’m tired or upset, I become more vulnerable so my binge voice is more likely to show up and start bullying me into throwing all the rules out the window.

Between these extremes is a balanced, flexible, supportive, and helpful self-care voice that can mediate the dialogue between your binge voice and restrictive voice. It is unconditionally compassionate, affirming, and accepting. Throughout this book, we use the phrase, “Of course!” to validate your thoughts, feelings, and actions as being normal and understandable given the circumstances. It’s like saying, “I totally get why you thought, felt, or did that!” This validation and unconditional acceptance creates a safe environment for experimenting with new thoughts, feelings, and actions. Your self-care voice is the voice of kindness and wisdom. Samantha’s self-care voice is like a loving parent.

My self-care voice is gentle and loving and wants the best for me. “Of course you’ll be distracted by those other voices—they’ve been around a long time—but I’ll always care for you, no matter what. You are beautiful and loveable, and worth taking good care of. Let’s get centered. Take a few deep breaths. See? Listen to your body. Are you hungry? No? There’s plenty of food; you can have it later when you get hungry. For now, just rest. Your needs are important. You are enough.”

As you nurture and strengthen your self-care voice, the other voices begin to fade. As you reprogram your mind and cultivate this way of thinking, you will create a self-perpetuating loop of self-care.

REPROGRAMMING YOUR MIND

Each time you choose not to activate your old trigger-thought-feeling-action-result sequences, you weaken the connections. It’s as if the wires rust and eventually break. Further, each time you choose a different action, you create a new connection. With repetition, you’ll hardwire these new pathways—like insulating the wiring. Your new thoughts and responses become your new habits.

To help you start the process of reprogramming your mind, let’s consider three helpful options for dealing with your triggers: reduce them, rethink them, and recreate them.

Reduce Them

One way to handle certain triggers is to reduce your exposure to that person, place, event, or other trigger. In this way, you prevent the thoughts from coming up in the first place. For example, if there are usually snacks in the break room, you could keep water at your desk so you can avoid the break room altogether.

Rethink Them

You’ve probably heard or read advice like, “Avoid eating at restaurants” or “Eat before you go to a party.” While these are examples of reducing your exposure to certain triggers, it is impossible—and undesirable—to permanently eliminate every conceivable trigger. If you tried, your life would become very small!

Fortunately, it is possible to reprogram your mind so you don’t have to live in fear of encountering a trigger. When you recognize one of your triggers and watch the automatic thoughts that follow, you’ll discover that you have many options. Replacing automatic thoughts with new, more effective thoughts disrupts the old pattern. For example, if you noticed that a store special triggered you to think, “Buying three candy bars is a better deal than just one!” you could change your thought to, “It is NOT a better value to buy and eat more than I need.”

Recreate Them

When you turn a trigger for overeating or bingeing into a trigger for self-care, you create a completely new pattern for yourself. For example, “When I’m hungry, I’ll eat what I love. When I’m bored, I’ll do something I love.”

Our brains have a natural tendency to focus on negativity and mistakes. You can replace this mistake-focused wiring with new behavior wiring by mindfully noticing when you rethink your old triggers, experience a positive feeling, or choose a new behavior. Whenever you make even a baby step in the direction you want to go, pause to soak in the awareness for 20 to 30 seconds. When you take time to notice your new trigger-thought-feeling-action-result sequences, you will strengthen the wiring.

To give you more examples of how to reduce, rethink, and recreate your triggers, we’ll explore four common types of triggers: the sight and smell of food; special occasions and holidays; social events; and high-risk times. These are only examples; explore your own triggers and experiment with various options to see what’s most effective for you.

TRIGGER: The sight and smell of food

Most people are food-suggestible. Just seeing or smelling appetizing food can trigger the urge to eat. We live in a food-abundant environment so food is everywhere—on billboards, on television, and in magazines—ironically, often next to the articles about the latest wonder diet! That’s because marketers know how food-suggestible most people are. There is serious marketing science for the retail store layout and food placement to trigger impulse purchases. Have you ever wondered why there is candy in the checkout lane at hardware and craft stores?

Reduce: Experiment with the following ways of decreasing your exposure to the sight and smell of food when you’re not hungry: Put tempting foods behind other foods in your cabinets and refrigerator—you’ll be surprised by how often you actually forget about them. If other family members or coworkers leave food out, politely ask them to put it away where it can’t be seen. Make a list of specific grocery items and shop around the perimeter of the store, only venturing down the aisles for items on your list. You can also leave the room during the television commercials, skip cooking shows, and page quickly past the food ads, diets, and recipes in magazines.

Rethink: When you’re in a nonfood establishment such as a hardware store that has tempting snack displays, tell yourself, “I won’t be a puppet for their profit!” When you’re exposed to food marketing, remind yourself that you’re the one who decides when and what you’ll eat.

Recreate: If you see appetizing food and suddenly feel like eating, move away from it for a quick Body-Mind-Heart Scan. If you’re not hungry, you can still appreciate the appearance and aroma without eating it—just think of it as a feast for the eyes. Then look for other ways to delight your senses, such as flowers or candles, and find opportunities to create pleasure for yourself that don’t involve food. If you are hungry, for example, while preparing a meal, turn your focus instead to the mindful experience of cooking. Admire and smell each ingredient. Notice the movements of your hands as you chop and stir. If you need to taste to adjust seasonings, take only a small amount and notice whether you’re less hungry at mealtime as a result. If you feel overly hungry while you’re cooking, perhaps you take a break to eat your salad first to take the edge off.

TRIGGER: Special Occasions and Holidays

Food and celebration have been intimately connected throughout history—mothers and grandmothers cooking special meals for their families, couples sharing romantic dinners on Valentine’s Day. Holidays can be especially challenging because of all the social ties to traditional foods and certain people. Special occasion mentality is more likely to trigger bingeing when you think in all or nothing terms. Likewise, if you only give yourself permission to eat enjoyable foods on special occasions, it perpetuates scarcity thinking—the belief that there isn’t enough so you have to get as much as you can, when you can.

Reduce: Since these special occasions come around on a predictable schedule, you can plan ahead to reduce your exposure to your trigger foods and situations. Steer away from the holiday candy aisles and wait until the last minute to buy holiday foods. Plan special events around activities other than eating.

Rethink: Be aware of automatic scarcity thoughts like, “I love Grandma’s cookies! I’ll get my fill now since I won’t have them again until next year!” Cultivate abundance thinking instead: “These holiday cookies will be back before I know it!” or “I can make turkey and mashed potatoes anytime I want.”

Recreate: Rather than feeling that you have to break the food-celebration link altogether, you can enjoy special meals while still using hunger and fullness to guide you. When you notice yourself thinking, “I’ll have a little bit more; it’s a special occasion!” you could think, “I don’t need an excuse to have a wonderful meal so why use a special occasion as a reason to overeat?” or, “If this occasion is so special, why would I want to ruin it by eating until I feel uncomfortable?” Keep in mind that special foods will be even more special when you eat them mindfully, focusing on the appearance and flavors of the food, the ambience, the other people, and the reason you’re all together. You could choose to think, “It’s wonderful that Grandma is passing on these traditions. I’ll savor every bite and every moment!”

TRIGGER: Social Events

Most social events are full of Pavlovian bells for habitual eating—movies and popcorn, sports and hot dogs, dates and dinners, networking and appetizers—the list goes on and on! Social norms and pressure to eat certain types and quantities of food can distract you from paying attention to your own body’s needs so it’s pretty easy to ignore your hunger signals, eat mindlessly, and become distracted from noticing fullness.

Reduce: Instead of making food the main event, focus on the movie, the game, and other people. Find ways to socialize that don’t center on eating. For example, you could treat your family to a trip to the science museum instead of going out for lunch or ice cream. If business entertaining usually involves food and drinks, make plans to do business while playing golf or during walk-and-talk meetings.

Rethink: If you notice yourself thinking, “Wow, there’s so much great food! I have to try everything,” you could change your thought to “Wow, there’s so much great food! I can find exactly what I want” or “I don’t want to fill up on ordinary foods so I won’t enjoy the foods I really love.”

Recreate: Enjoy the whole experience and make eating a conscious part of the activity. When food is a natural part of an event, it helps to time social meals to match your natural hunger rhythms or adjust your eating that day so you’ll be hungry (but not too hungry!) so you can enjoy the food. And there is no need to deprive yourself; just focus on quality and enjoyment rather than quantity and habit. For example, if you really love movie popcorn, buy an amount that will be satisfying and savor it one delicious kernel at a time rather than consuming a whole bucket mindlessly.

Trigger: High-Risk Times

Most people have times of the day that are high risk for overeating or bingeing. For example, you may experience a late afternoon energy slump, have a tendency to munch when you come home from work, or binge late at night while watching TV. These high-risk times might correspond to your natural hunger rhythms, or they might be times when you’re tired, lonely, bored, or otherwise at risk for a binge. For many people who struggle with binge eating, being alone is a potentially high-risk time because it creates the opportunity and privacy for their secret binge activity.

Reduce: Think about the times when you are most at risk and develop alternate plans. For example, you could schedule a class or other activities before dinner.

Rethink: Since eating is sometimes used as a transition, for example, from work to home or from evening to night, think about other ways to help you relax or unwind. Perhaps you create a special recharge or transition ritual, such as saving a favorite magazine or book to read, calling a friend, walking your dog, or taking a hot bath.

Recreate: Rather than looking forward to being alone to binge, think of it as an opportunity to practice self-care. “I can take a bubble bath without interruption” or “I can play my music as loud as I want or dance if I want to!”

Let’s see how Samantha used Reduce, Rethink, and Recreate to change her mind.

I reduced one of my triggers for bingeing on ice cream by taking a different route home from work to avoid that billboard. I also needed to rethink my all or nothing attitude about ice cream, because clearly, it wasn’t working. I decided that I could go out for an ice cream cone whenever I wanted, but for now, I won’t keep ice cream in the house. My self-care voice helped me recreate my thoughts by reminding me that I deserve sweetness in my life. I came up with a dozen other ways to bring more pleasure and happiness into each and every day. One of my favorite ways to add joy is picking my granddaughter up from school and having an ice cream cone together!