8

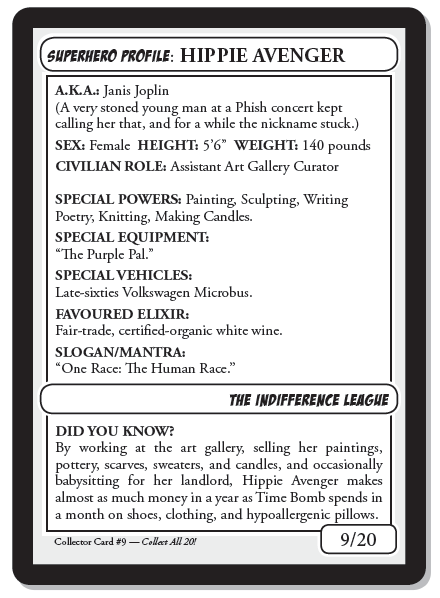

HIPPIE AVENGER

“Go in peace, my daughter. And remember that, in a world of ordinary mortals, you are a Wonder Woman.”

— Queen Hippolyta, from the TV

series Wonder Woman, 1975–1979

HIPPIE AVENGER

“Go in peace, my daughter. And remember that, in a world of ordinary mortals, you are a Wonder Woman.”

— Queen Hippolyta, from the TV

series Wonder Woman, 1975–1979

Hippie Avenger thinks that her Not-So-Super Friend nickname is a bit of a misnomer.

Sure, she still drives the pea-green late-sixties Volkswagen Microbus she inherited from her parents, but it isn’t because of any sentimental desire to Keep on Truckin’ or be Too Rollin’ Stoned, to quote just two of the dozens of bumper stickers permanently affixed the van’s exterior. The old Microbus gets her from point A to point B most of the time, and she can’t really afford to replace it.

And, sure, she still pulls her long, curly black hair into a ponytail when she doesn’t have time to wash and style it, and she still wears the same sort of loose-fitting pastel-coloured smocks and Birkenstock sandals that she’s worn since childhood, but none of these things are necessarily symbolic of any great dedication to the idealistic convictions of a bygone era. They are just habits.

And, sure, she doesn’t own a cellphone or an MP3 player or a laptop computer or a big-screen TV or any of the other technological devices that seem so important to other people, but it isn’t because she is conscientiously boycotting the material trappings of capitalism, nor is she purposely trying to keep money and therefore power out of the hands of the Military-Industrial Complex. She simply doesn’t care about any of that stuff. When she is outside her apartment, she doesn’t want to listen to digitized music or blather endlessly on the phone, she just wants to look at the trees and listen to the wind (or look at the buildings and listen to the traffic, if that’s what happens to be around). She rarely ever checks her email or uses the Internet on her third-hand home computer, so why would she ever need a portable one? And television? When is there anything worthwhile on television?

Her lifestyle choices are not a matter of philosophy; they are merely preferences. Therefore, Hippie Avenger is not a true Hippie. She knows this all too well.

Her parents were genuine tie-dyed, pot-smoking, vegetable-eating, anti-war, anti-establishment, free-lovin’, free-wheelin’ Hippies. They both turned twenty in 1968, and were already Old Hippies when they finally brought their first and only Love Child into the world ten years later. Now pushing seventy, they are one of the few ragged old couples who still cling to the whole Peace, Love, and Joy thing, and they will still expound at length about the dream of Woodstock, and how it died for most hippies at Altamont, but not for them.

Unlike most other members of their generation, who talk as if they had been there when they really just watched the movies, Hippie Avenger’s parents had in fact journeyed to both Woodstock and Altamont, using the money they were supposed to spend on college tuition. They also went to Monterey, and they followed the Grateful Dead for an entire year, all in the same VW Microbus that their Love Child now uses for her weekly trip to the mini-mall to buy the commercial-industrial products that her parents so despise.

Yes, Hippie Avenger sometimes buys manufactured goods from corporate-owned stores. She eats factory-

packaged cookies made with unwholesome white flour and sugar refined from cane grown on non-unionized Third-World plantations. She knows that this is philosophically the wrong thing to do, but it’s just so much easier than making them from scratch, and they taste uniformly, predictably, okay. She also uses toothpaste manufactured by the same company that made one of the ingredients for Agent Orange during the Vietnam War, because brushing with baking soda like her parents do makes her breath smell like a yeast infection. She even uses disposable razors and commercially produced scented foam to shave her armpits.

Does she feel guilty about doing any of these things? Of course she does. Her parents would be horrified. Her socio-political guilt wages war with her preference for minty freshness every time she brushes her teeth. Whenever she exfoliates under her arms or around her pubic patch, she hears her mother scolding her for “caving in to corporate commercial social norms.” If her father knew about his daughter’s flagrant use of underarm deodorant, he would launch into a tirade about how “the minions of commercialism have spent millions of advertising dollars to make us fear the scent of our own humanity.”

And yet, still she eats Chips Ahoy! cookies, brushes with Crest, exfoliates with Gillette, and masks the scent of her humanity with Lady Speed Stick. She knows that she really isn’t a hippie at all. She only sort of looks like one. So her nickname, Hippie Avenger, is not quite right. But so far nobody has come up with anything better.

She sighs as she heaves a burlap bag into the back of the Microbus, which contains a couple changes of clothes, her toothbrush, hairbrush, razor, and the only portable, battery-powered technology she owns: a purple, plastic-and-rubber, quasi-penis-shaped vibrator. Of course she would rather feel a real, organic penis moving inside her, and of course she would prefer the tongue of a real man flicking at her sensitive clitoris, but in the meantime she’s grown quite fond of her Purple Pal. Certainly it brings her more pleasure than a TV, a cellphone or a laptop computer ever could.

The Orgasm is one of the few luxuries that Hippie Avenger was taught not to feel guilty about wanting. She considers slipping back inside her apartment for a quick self-pleasuring session, but she’s already an hour behind schedule. She is always running late, probably the result of growing up in a home free from the tyranny of clocks.

She climbs up into the driver’s seat of the Microbus, wondering if she’s remembered to unplug the coffee percolator, or to lock the door to her apartment above the detached, bungalow-sized garage of her landlord’s suburban stucco-covered-cardboard McMansion. She shrugs. If her place gets robbed or burns down it won’t make any difference to her; she doesn’t own anything of real value, either monetary or sentimental. It’s one of the few old bumper stickers on the VW that actually reflects her own feelings: THINGS ARE JUST NOT MY THING.

Hippie Avenger slides the key into the ignition on the scratched-up steering column and turns it. Nothing happens. She wiggles the key and tries again. Still nothing. Then she notices that the switch for the headlights is pulled out.

Damn it! I left the lights on again.

She walks around to the front of the McMansion. Her landlord and his wife have already departed for the holiday weekend, so she won’t be able to beg for yet another jump-start.

Great. Like, now what am I going to do?

Hippie Avenger doesn’t feel comfortable approaching one of her neighbours for help, because she still hasn’t met any of them (typical of these soulless, anti-community, commuter-culture subdivisions, her parents would be quick to point out). Besides, she doesn’t actually know how to open the engine compartment on the Microbus, or where to connect the clamps on the ends of the tangled jumper cables. It’s her landlord who always jump starts her van, and she has never paid much attention to how he does it. He is an expert on the mechanics of lawn mowers and weed trimmers and gas grills and other suburban gadgets that might as well be sub-molecular-particle accelerators as far as Hippie Avenger is concerned.

She climbs the stairs to her garage-top apartment. She has, in fact, left the door unlocked. In the kitchen, she switches off the coffee percolator, reaches for the telephone, and dials Mr. Nice Guy’s number. He won’t mind swinging through Guelph to give her a ride to The Hall of Indifference; that’s why they call him Mr. Nice Guy. She gets his voice mail, though; he’s probably en route to the cottage already, and law-abiding, safety-conscious Mr. Nice Guy would never talk on his cellphone while driving.

Next she tries Miss Demeanor; a recorded message informs her that “The caller you are trying to reach is currently unavailable,” which means that Miss Demeanor is probably engaged in another war of attrition with her cell service provider.

Hippie Avenger doesn’t have a current number for The Drifter, so there is really only one other choice. She hesitates before dialling.

Maybe she should just stay home for the weekend. Of the eight original Not-So-Super Friends, Hippie Avenger and The Statistician have the least in common. They probably wouldn’t be friends at all if not for the others. It might actually be less unpleasant for Hippie Avenger to spend the entire long weekend trapped in this deserted-for-the-weekend, miles-from-anywhere suburb, than to suffer that smug, philosophically-superior look on The Statistician’s face as he jump starts the Microbus. Even worse, if the persnickety VW refuses to co-operate, she might have to face the horror of spending three hours in a car with The Statistician and his whiny, high-maintenance, country-club wife.

She looks out through the kitchen window, over the identical squares of chemically fertilized golf-green lawn and the identical asphalt-paved driveways of the identical beige-stucco McMansions lined up in perfect geometric order.

Like, why did I ever move here? My parents were right. I don’t belong in the suburbs, no matter how cheap the rent. I really need to get out of here.

Like, now.

She breathes in slowly, and then she calls The Statistician.