In March 1987, South African Army reconnaissance teams deep in Angola detected big movements of Cuban and Angolan Marxist troops from the centre of that country towards the vast and empty region of the southeast.

The recce units, who spent almost as much of their working lives inside Angola as in their home bases, had located forces that the SADF (South African Defence Force) would soon engage in its biggest land battles since World War II.

Jan Hougaard, deputy commander of the SADF’s 32 Battalion, guessed then that a major offensive was about to be launched against South Africa’s ally in Angola, the UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola) resistance movement. He knew also, from past precedent, that his men would be the first to be thrown into the fray.

Commandant Hougaard’s hunch was confirmed in May when 32 Battalion, also known as the Buffalo Battalion, was ordered to make a plan to destroy a major bridge across the Cuito River. The bridge, some 400 km inside Angola, was the only one across the river from the little town of Cuito Cuanavale, on the west bank, towards the east and the stronghold of UNITA.

‘We sent out teams on close reconnaissance,’ said Hougaard, regarded by many of his contemporaries as South Africa’s best guerrilla-style fighter. ‘There were two Angolan brigades, with Cuban support, defending the town. Its outskirts began just 500 m west of the bridge, a strong metal and concrete affair with a tarred surface that could take vehicles and tanks. So we presented our plan. We would have to accept heavy casualties, but we were prepared to do it.’

In the event, 32 Battalion’s attack on the Cuito bridge never took place. The plan was vetoed after it reached the Chief of the SADF, General Jannie Geldenhuys, and the Chief of the Army, Lieutenant-General Kat Liebenberg.

The generals probably reckoned that not enough inconvenience would be caused to the gathering Angolan-Cuban forces to justify heavy SADF losses. The bridge’s destruction would only slow the momentum of the enemy build-up. Its loss would be easily compensated for by the superb TMM mobile bridging equipment supplied by the Soviet Union in great quantities to its client in Angola, the Marxist MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola) government.

The generals’ decision allowed the build-up by the Cubans and the MPLA army, known as Fapla (Forces Armadas Popular de Angola – People’s Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola), to go on undisturbed until August, by which time the SADF had begun moving small fighting units deep into Angola to counter the enemy thrust.

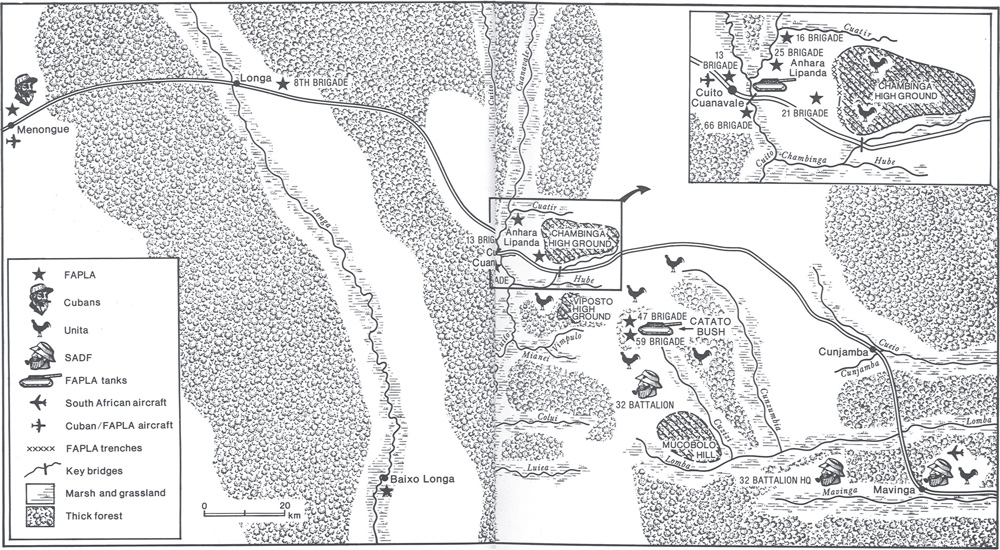

The two brigades detected by 32 Battalion’s recces had by August grown to eight. Five Fapla brigades, the 16th, 21st, 25th, 47th and 59th, had pushed men and equipment across the Cuito River bridge whose destruction had been vetoed by the South African generals. A sixth brigade, the 66th, was deploying along the western bank of the Cuito, north and south of the river bridge, thus protecting the eastern perimeter of Cuito Cuanavale. A seventh brigade, the 13th, was in Cuito Cuanavale itself, giving direct protection to the town and its military airstrip. The eighth brigade, appropriately the 8th, was ferrying men, weapons and other equipment into Cuito Cuanavale from Menongue, 160 km to the west.

‘There were still people in the higher echelons of the SADF who didn’t believe there was an offensive imminent even when the Faplas had pushed two of their brigades across the river,’ said Jan Hougaard, a thickset Afrikaner whose brown hair and beard had been bleached blond, his white skin cooked dark brown by constant exposure to the Angolan and Namibian sun. ‘But 32 Battalion and a lot of intelligence organisations and other people had no doubt it was coming. UNITA had troops opposite Cuito Cuanavale monitoring those forces, and UNITA’s Chief-of-Staff, Brigadier Demostenes Chilingutila, was busy bringing his guerrillas from other military regions of Angola to counter the offensive he expected.’

Captain Herman Mulder, 28, the senior intelligence officer of 32 Battalion, was also convinced of Fapla’s serious intentions. With Colonel Jock Harris, 32 Battalion’s commanding officer, he was flown by helicopter at night from Rundu (the SADF’s forward base in South West Africa/Namibia) some 260 km into Angola in late June to meet SADF Colonel Fred Oelschig, who since early May had been liaising with and training UNITA’s 5th Regular Battalion which was monitoring the Fapla build-up.

Harris and Mulder advised UNITA on stand-off mortar bombardments they were making against the Fapla concentrations. But Mulder was more concerned to know where the enemy brigades were each day and whether they showed signs of splitting up into battalion attack formations.

Mulder, Harris and Oelschig became the first South Africans to come under enemy fire in the Fapla offensive. Mig-21s of the Angola Air Force were already in the air regularly. And on 27 June 1987, as the three SADF men were working in a UNITA radio vehicle, parked at the source of the Cunzumbia River, Migs attacked the base.

‘They came in to hit a diesel storage bladder,’ said Mulder. ‘The nearest missile to us landed 85 m away. We decided to get out of the area when Fapla began pounding the base with D-30 heavy artillery and 120 mm mortars.’

It was at this stage – late June, early July – that SADF operational commanders submitted proposals to Defence Headquarters, Pretoria, for countering the Fapla/Cuban build-up. The meeting, between Harris, Oelschig and the officer commanding the SADF’s northwest Namibian sector, Colonel Piet Muller, at Harris’ field HQ south of the Lomba River, became known as ‘The Night of the Three Colonels’. It was a long and traumatic night with a lot of heavy arguing. The consensus finally was that the developing enemy offensive was too big for them to handle without the commitment of more South African forces and the creation of some sort of SADF brigade structure.

The military situation on the ground – 13 August 1987.

The favoured plan of the ‘three colonels’ involved sending a major battle group from Namibia northwards along the western bank of the Cuito River, attacking Cuito Cuanavale from behind, and controlling the narrow road from Menongue along which logistics were being ferried to the brigades.

By now the CIA was sending the SADF intelligence assessments on the Fapla/Cuban build-up from General Rafael Del Pino Diaz, whose extensive debriefing in Virginia, after his defection from Cuba, was almost at an end. Del Pino’s advice also was that cutting the Menongue-Cuito Cuanavale supply road was the best and most logical way of stopping the offensive. It would be a tactical error for the South Africans and UNITA to concentrate their forces on Cuito Cuanavale.

‘Strategically, it was on,’ said one senior officer involved in planning the assault on the Menongue-Cuito road. ‘But politically we didn’t get permission.’

That decision was made at the highest level by the State President P W Botha. His fear, and that of his Cabinet, was of the international outcry that would follow if regular South African troops were perceived to be fighting several hundreds of kilometres inside Angola. For historical and strategic reasons it believed to be sound and just, Pretoria felt its involvement in the Angolan conflict was fully legitimate. But an attack towards Cuito Cuanavale from the west could not have been hidden and substantial casualties would have been inevitable. South Africa was already under heavy international pressure, in the form of sanctions, disinvestment and boycotts of various kinds, over its domestic race laws and the denial of the vote to the black majority. Few countries would be disposed to understand the presence of a major South African military force in the territory of a sovereign black African state: instead, it would be used as another stick to beat a country trying desperately to re-establish international respectability.

The South African Cabinet instead approved the commanders’ secondary plan: a thrust into the area east of the Cuito River – a vast, sandy, tree-covered wilderness called the ‘Land at the End of the Earth’, an epithet applied by Angola’s Portuguese colonial rulers who reserved the region for big game hunting – to prevent Fapla from capturing UNITA’s strategic stronghold of Mavinga.

UNITA had held Mavinga since 1980. Once a town with barely a thousand inhabitants living along its two streets lined with orange trees, it had been deserted for 12 years and was now crumbling back into the red earth of Africa. But nearby was an important airstrip used by heavy transport planes bringing weapons and supplies to UNITA from Zaire, South Africa and other African points of origin. The airstrip and the surrounding UNITA bases stood on top of a plateau just south of the Lomba River: if UNITA were to lose Mavinga, the way would again be open, as had been the case in 1985, for Fapla and the Cubans to prepare a major drive towards Jamba, UNITA’s ‘capital’ 250 km southeast of Mavinga. With the collapse of UNITA, there would follow the collapse of Pretoria’s military and diplomatic game-plan for the southern African region.

South Africa had long been co-operating secretly with Jonas Savimbi, the UNITA leader, in the conviction that his movement enjoyed majority Angolan support against the Soviet-backed MPLA government. South Africa had also made its withdrawal from Namibia, administered by Pretoria in defiance of United Nations condemnation, contingent upon the return home of Cuban troops supporting the MPLA in Angola. It was UNITA which kept constant pressure on the Cubans and made it possible for Pretoria to insist on a ‘double zero’ pullout – South Africa from Namibia and Cuba from Angola – first proposed by P W Botha in 1978. If UNITA were to be eliminated there would no longer have been a clear ‘moral equivalence’ between the Angolan and Namibian situations; and South Africa would have faced a large Cuban force on the Namibia border demanding liberty for the territory with wide international support. The South African government had already concluded that Namibia’s independence was inevitable, but that it would not come at the behest of Havana, whose military dictator Fidel Castro was demanding for Namibians and South Africans the kind of freedoms he denied his own fellow Cubans. Much as South Africans desired an end to their pariah status in the international community, they were not so soft-headed as even to consider succumbing to this kind of hypocrisy. They knew what the consequences would be of a militarily and ideologically confident Cuban force sitting on the Namibian border free of any challenge from within Angola: it would inevitably have meant a new kind of war for South Africa of major proportions and unpredictable consequences.

Approving the field commanders’ secondary plan, South Africa’s politicians told the fighters that the Fapla offensive must be halted and UNITA’s power base strengthened. They further decreed that the SADF’s involvement would be secret and sufficiently limited to be ‘plausibly deniable’. Any successes would be attributed to UNITA. The role of the SADF force would be purely defensive, not offensive. There was a further set of instructions which caused wry and sometimes bitter amusement among the combat officers: no men must be lost; no equipment must be lost; and you must achieve all your objectives.

‘Those are very difficult and heavy restrictions to put on anyone who is supposed to be fighting a war,’ said Jan Hougaard. ‘But that’s the way we work in the SADF. We can’t afford to lose one guy.’