Colonel Deon Ferreira’s new orders were to clear all enemy forces from the eastern side of the Cuito River – ‘Savimbi-land’ – before 15 December 1987 as well as to inflict maximum casualties so that no fresh Fapla offensive could be launched in 1987 or 1988. 15 December was an important date because all those national servicemen nearing the end of their two-year call-up had been promised by General Liebenberg that they would be home in time for Christmas.

But there were major problems to be overcome if the wishes of the political bigwigs and top military brass in Pretoria were to be granted, according to Jan Hougaard. ‘We were a small force of 1,500 and we still had a hell of a big force against us. There were 15,000 Fapla troops between us and Cuito Cuanavale. The Ratel-90s had performed beyond all expectations in their “guerrilla” role against tanks during the Fapla offensive. But with their light armour and the limitations of the 90 mm gun, they were inadequate by themselves for the task of pursuit and annihilation. For that we needed tanks.

‘All our planning had been for a defensive operation. Overnight we were meant to switch onto the offensive and begin a long-distance chase of a big conventional army. Colonel Ferreira foresaw that as we moved north our logistics problems would increase and the volume of supplies we needed would multiply. We already had very, very long logistical lines. It was incredible: you’re not actually meant to wage war in that way, army academies tell you. The further north we pushed the more critical we knew the logistics would be for our artillery batteries. They were our key weapons, but they use a hell of a lot of ammunition, and if you think you’re going to run out of it you just can’t shoot freely.’

There was another problem to consider in the shape of the SADF’s UNITA ally. Although probably the finest guerrilla army in Africa, UNITA had very limited experience or expertise in the more conventional role that would now be expected of it.

There was one worry, however, that Ferreira did not share with Pretoria, said Hougaard. ‘It was clear to those of us on the ground that the Fapla offensive was over for 1987. On 5 October our EW people intercepted messages from Cuito Cuanavale ordering all the Fapla brigades to withdraw north to an area at the source of the Cunzumbia River and to dig in. There were people in the higher echelons in Pretoria who believed those brigades still had the capacity and the willpower to come south again. But we knew they could never do it.’

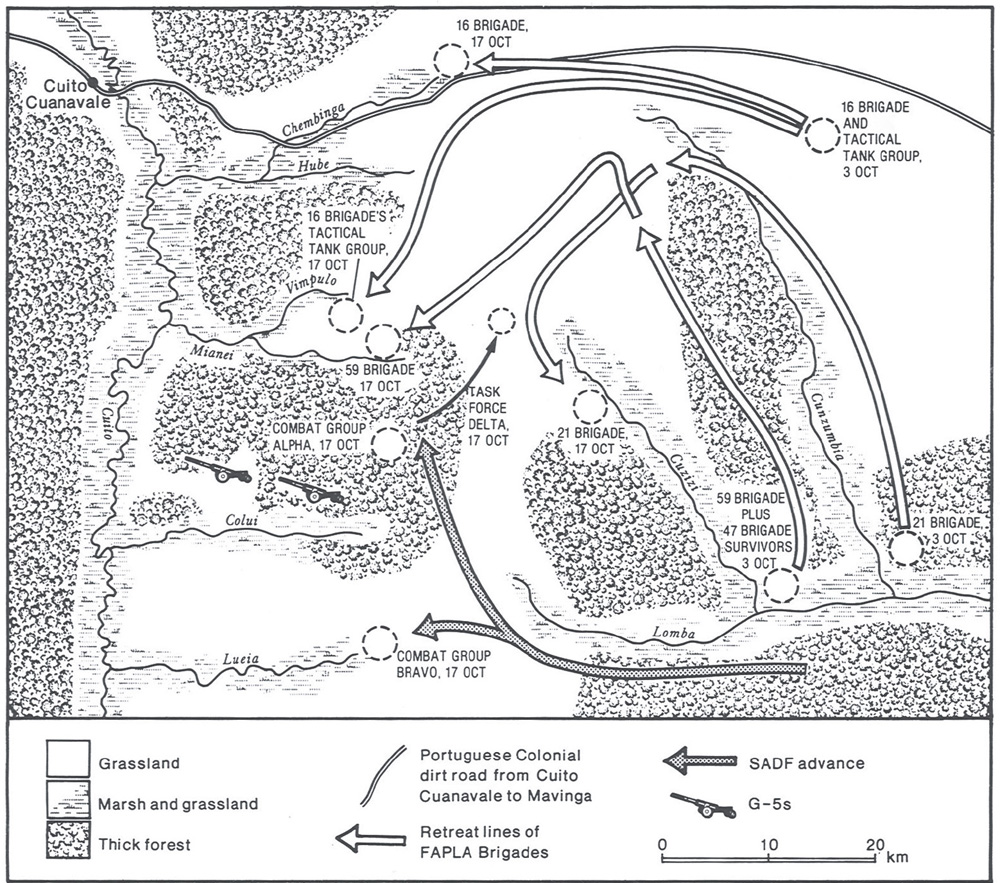

The withdrawals of 59, 21 and 16 Brigades and the tattered remnants of 47 Brigade to the Cunzumbia source were accomplished relatively easily and methodically, despite harassment from SADF artillery and SAAF bombardments. ‘Our troops on the ground were totally buggered,’ said Hougaard. ‘They couldn’t give chase. They needed sleep and replenishment. A big effort was made to bring in fresh meat and vegetables to them together with cold drinks and beer.’

Ferreira had been promised an additional force of mechanised infantry, the 4th South African Infantry Battalion (4 SAI), as soon as the young national servicemen in its ranks had been fully organised by their regular officers; a squadron of 13 Olifant tanks; an additional battery of eight G-5 guns; and a troop of three G-6 guns, the new self-propelled version of the G-5. But it would be several weeks before these heavyweights arrived. Meanwhile, Ferreira could not afford to twiddle his thumbs and allow the Fapla brigades to regroup and bring in new supplies at their leisure. He needed to act.

His first major decision, taken on 8 October, was to move the SADF combat groups and artillery 45 km rapidly northwestwards from south of the Lomba to positions just south of the Mianei River, a tributary flowing due westwards into the Cuito. With typical temerity, Ferreira had the first units moving towards the new front even before formal approval was given by Pretoria.

Ferreira’s aim was threefold – to get the G-5s into position to be able to bomb the military airfield at Cuito Cuanavale, well within the big guns’ range just 35 km from hilly ground south of the Mianei; to provide a solid protection force for the G-5s, which on no account whatsoever could be allowed to fall into enemy hands; and to infiltrate units behind Fapla lines to harass the brigades, raid in rear areas and disrupt logistics.

Ferreira also despatched recce groups with artillery observers to take up positions northeast of Cuito Cuanavale on high ground between the Dala and Cuatir Rivers with an uninterrupted view over the enemy-held town. These groups were trooped in by Puma helicopters by night to within walking distance of their positions some 350 km inside Angola.

It was critical to bring Cuito Cuanavale under bombardment. Sixteen Mig-21 and Mig-23 fighter-bombers were permanently based there together with six MI-24 Hind helicopter gunships. From take-off at Cuito Cuanavale it was just three minutes flying time before the Migs were over the Lomba or Mianei. If Cuito Cuanavale could be closed down, the nearest Fapla air base would be at Menongue, 175 km to the west. Flying time from Menongue would be 17 minutes and the Angolan Air Force planes would have a shorter holding time over the SADF for fuel reasons. The South Africans would also have advanced early warning of impending air assaults from recces infiltrated around Menongue.

On 8 October Combat Groups Alpha and Charlie moved off early in the morning under Commandant Bok Smit. They headed westwards along the south bank of the Lomba before swinging northwestwards around its source across the watershed towards the source of the Mianei. Commandant Robbie Hartslief ’s Combat Group Bravo followed about 10 km behind.

That day the SADF ignored its golden rule about thwarting the air superiority of Fapla’s Migs and Sukhoi-22s by sticking to night movements – and it paid the price. Two Mig-21s swept in low under top cover provided by two Mig-23s and destroyed a Ratel-90 of Combat Group Alpha, killing one crewman and seriously wounding four others. It was scant compensation that UNITA brought down one of the Mig-21s with a Stinger and that the pilot’s body was found in the debris.

Captain Piet van Zyl had been assigned with his Foxtrot company of 32 Battalion infantrymen to a newly formed unit christened Task Force Delta to act for the Mianei combat groups as a reconnaissance-cum-raider unit laying ambushes behind enemy lines.

Task Force Delta, under the command of 32 Battalion’s Major Lourens du Plessis, comprised Foxtrot company of 32 Battalion infantrymen in Buffels; two jeep-mounted 106 mm recoilless anti-tank guns with crews; three Unimog light trucks; four 81 mm mortars with crews; and two Milan anti-tank missile teams.

Task Force Delta reached the source of the Lomba on the night of Thursday 8 October, at the same time as Bok Smit’s 100 or so vehicles of Combat Group Alpha.

‘There were vehicles moving through the bush like it was rush hour in Johannesburg,’ said Van Zyl. ‘There were military police bringing the machines through in single file. They moved slowly and close together so as to maintain contact. Bok Smit, not in the best of moods after the bombing of the Ratel, told us we would have to wait until all his vehicles had passed. That was going to take hours, so we slept at the source of the Lomba and then moved 20 km northwards to join up with General Ben-Ben and UNITA’s 3rd Regular Battalion four kilometres west of the source of the Cuzizi.’

Four weeks followed of inconclusive manoeuvring and skirmishing for the SADF combat forces while they waited for the tanks and 4SAI to arrive from South Africa.

Ferreira took the opportunity to reorganise his small brigade. Combat Group Charlie, ‘the eternal reserve,’ was dissolved and merged into Combat Group Alpha, so that now there were just two combat groups – Alpha, under Bok Smit, and Bravo, under Robbie Hartslief, plus the Task Force Delta marauders.

Ferreira also persuaded Savimbi to move five UNITA units, in addition to the 3rd Regular Battalion attached to Delta, into the watershed area between the Hube and Chambinga headwaters and those of the Cuzizi and Cunzumbia to harass Fapla and attempt to interrupt its logistics.

Fapla HQ at Cuito Cuanavale sent 25 Brigade across the Cuito River with new supplies for 59, 21 and 16 Brigades. The convoy, accompanied by Soviet advisers, included ten replacement T-54 tanks and half-a-dozen BM-21 Stalin Organs. Another Fapla brigade, 66, was sent across the Cuito to guard the vital Chambinga River bridge. Ferreira was anxious to destroy this low, wooden span, since it provided the enemy with its most direct retreat route northwards. He hoped Task Force Delta with some of the UNITA battalions might be able to devise a way to demolish it.

On the evening of Wednesday 14 October the G-5s bombarded Cuito Cuanavale, the opening shots of a long-range artillery barrage on the key Fapla-held town which would go on for months. EW teams picked up Angolan messages saying that at least 25 Fapla soldiers perished in the first blitz from south of the Mianei.

The G-5s subsequently moved and redeployed constantly so that Fapla planes could not pinpoint their positions. The perpetual movement through the heavy forests south of the Mianei meant that only limited stockpiles of the G-5’s big shells and charge packs, weighing 43.5 kg and 23 kg respectively, could be built up. This contributed to the SADF’s growing logistical headaches, because trucks gasping into the Mianei area after more than 100 km of bundu-bashing from Mavinga were requisitioned as mobile stockpiles and could not unload immediately to make the return journey for more supplies. To save scarce ammunition, the G-5 battery was at times limiting itself to fire from one gun at a time.

The opening G-5 salvo on Cuito Cuanavale galvanised Fapla. That same day, 14 October, 59 Brigade received new supplies from 25 Brigade and on 15 October was ordered to move westwards to the Mianei to find the G-5s and destroy them. The commitment of an entire brigade to attempt to wipe out just eight guns was clear indication to SADF military intelligence of just how seriously Fapla’s morale was being dented by the G-5s. Elements of 21 Brigade followed 59 Brigade westwards as a reserve force while 16 Brigade, still largely intact, withdrew northwestwards to defensive positions at the source of the Chambinga River.

59 Brigade moved fast and aggressively. Its tank squadron, boosted to near full strength by the transfer of 21 Brigade’s remaining T-54s, smashed through thick bush, creating a path for other vehicles.

Lourens Du Plessis’s Task Force Delta was right on the tail of 59 Brigade. But, as Piet van Zyl explained, the men of Delta were frustrated in their desire to inflict damage by the enemy commander’s skilful use of the dense forest: ‘UNITA kept us informed all the time of how 59 Brigade was moving with the tanks in three lines forward, some 700 infantry following in vehicles and on foot, and with Fapla recces all around.

‘To inflict damage with the limited kind of weapons we had we needed to catch them in open shonas. The moment we moved against a big force with tanks like that in forest where we could not bob and weave we were bound to take big casualties. But all the time we were getting orders from HQ: “You must do something.”

‘We got very frustrated because they never moved into a shona and we weren’t able to make a single attack.’

Ferreira decided that Combat Group Alpha should attack 59 Brigade while the enemy was still deploying north of the Mianei source. If he waited, the G-5s would come under great danger; they would be engulfed if 59 Brigade made a rapid breakthrough.

Ferreira planned the attack for first light on Saturday 17 October. During the night Bok Smit’s Combat Group Alpha moved up to positions four kilometres south of the Mianei source. Robbie Hartslief ’s Combat Group Bravo deployed further south in reserve and ready to intercept 21 Brigade should it come storming down from the northeast to intervene in the battle. Lourens Du Plessis’s Task Force Delta was ordered onto the Viposto High Ground, just north of the Vimpulo River, with orders to intercept any force from 16 or 66 Brigades that might come down directly from the north.

‘War is to some extent like a card game,’ said Major Laurence Maree, leading 350 infantrymen of 61 Mech in Ratels as well as three Ratel anti-tank teams attached to Combat Group Alpha. ‘We had carried out careful reconnaissance just north of the Mianei source partly in the hope and partly in the conviction that 59 Brigade would choose to deploy there. And when they did just as we anticipated, Colonel Ferreira told us to give them a good knock.’

The first stage of the Fapla retreat, 3 October–17 October 1987

Bok Smit swung Combat Group Alpha east of the Mianei source where he picked up 59 Brigade’s tank tracks. The tanks had left the deployment area and were heading due west just to the south of the river. Unable to break its own path through the tangled trees, the SADF force pursued 59 Brigade behind a shield of UNITA infantry on the enemy’s tracks.

‘There was no other choice,’ said Laurence Maree. ‘The bush was incredibly dense and we had no tanks of our own to bulldoze an independent path. We made contact with the enemy just after 8 am. But, literally, we couldn’t see them and we never did see them. We only knew we were in a fight because shells began to bring down trees and branches around us. They had laid a simple ambush across their own tracks with three tanks, RPG-7s and B-10s (recoilless anti-tank guns). We ran full into it. They fired straight back down the tracks at us. We were in a very big confusion because the bush was so dense that the Ratels lost all their advantage of manoeuvre. Mig-21s were dropping bombs on us, but fortunately from the usual high level. UNITA hit one with a Stinger and later the SAAF Buccaneers and Mirages came in to help pin 59 Brigade down, hitting a couple of their Sam-13s and causing quite a few casualties.

‘Commandant Smit told us to get the hell out because we were in a killing ground. We only made it to safety because the G-5s and our other artillery reacted quickly and put down an intense and accurate bombardment on 59 as we retreated in a lot of disarray.’

Meanwhile, further north, Lourens du Plessis’s marauders arrived on the Viposto High Ground to find Sergeant ‘Frenchie’ of 32 Battalion and his recce team in position but minus a lot of equipment. Two days earlier ‘Frenchie’ had been told that the tactical armoured group attached to 16 Brigade was heading south with nine tanks to try to link up with 59 Brigade. He was ordered to investigate intelligence reports that an advance unit of the tactical group had already reached the Vimpulo River and built a bridge for the tanks.

‘I took my radio man, two UNITAs and an air force forward air controller with me,’ said Frenchie. ‘We picked up the tracks of the enemy and we stopped every 50 m to check that we weren’t walking into an ambush. The tracks eventually took us to the river. There was no bridge, but it wasn’t necessary because the water was so shallow that it was easy to ford.

‘We sweated heavily on that trip because we weren’t sure about what we might run into. We moved back a bit from the river, but the next morning the enemy’s advance motorised infantry team came back northwards across the ford and passed very close to us. We would have been dead if they had seen us. After they had passed my radio man started to freak with the strain of it all. His big eyes started to roll and then he just got up and ran off with the radio. He disappeared and one of the UNITAs followed him. So he left us alone without the radio. All we had was its long antenna!’

Frenchie and the remaining UNITA soldier now went down to the river to fetch water. What they did not know was that a platoon of Fapla soldiers from the tactical group was still on the southern side of the river. Frenchie and the guerrilla had started filling their flasks when heavy fire opened on them from inside the treeline across the river. They fled across the stretch of open grassland into the cover of the northern trees, leaving their rifles, compasses and water bottles behind in the rush.

As he ran, Frenchie was shocked to see the air force man sitting in a tree, so clearly visible that it was obviously him who had alerted the Fapla troops. The tree was completely isolated and it had no branches left on it,’ said Frenchie. ‘It was like a telephone pole in an asparagus field. I thought: he’s gone mad. So I had to go and pull him down so that we could all move away. We were lucky to escape with our lives.’

Lourens du Plessis gave Frenchie new supplies and sent him on his way back to HQ before planning an ambush of the tactical group by Task Force Delta. When all the members of the tactical group’s advance unit had moved back northwards Du Plessis ordered Piet van Zyl and a sergeant to lay mines both to the north and the south of the Vimpulo ford. They had laid more than 50 anti-tank mines by the time they began to hear the tactical group’s tanks changing gear as they came southwards.

‘We’d hardly finished when Major du Plessis told us we’d been ordered by Colonel Ferreira not to attack the tactical group but to stalk it and establish targets for the G-5s,’ said Van Zyl. ‘So we had to go back and defuse and lift all those mines. We were working against time. We were all totally frustrated because we wanted to fight. Du Plessis is a man who really loves to fight, so Colonel Ferreira repeated his orders to him several times not to shoot. We could see the tanks as they came down to the ford, but we had to stay hidden. Then the G-5 shells started landing and a few vehicles with the tanks were shot out. The column stopped moving.’

Battle Groups Alpha and Bravo and Task Force Delta now had 59 Brigade, 16 Brigade’s tactical group and advance units of 21 Brigade pinpointed. The major objective became to keep 59 Brigade isolated; prevent it being reinforced; and continue softening it up with artillery and SAAF bombardments until a major ground attack became possible. The tactical group was shelled so heavily that on 21 October it gave up its attempt to join 59 Brigade and withdrew its tanks northwards.

The SADF artillery was greatly helped in the task of pinning down the enemy by recces and forward observers who penetrated the perimeters of 59 and 21 Brigades and sat inside them in immense discomfort and fear for their lives as they guided in shells on precise targets. Piet Fourie, for example, was inside 21 Brigade’s lines for four days, sometimes within 25 metres of Fapla soldiers. Fourie gave invaluable information to Pierre Franken – at this time directing the MRL ‘Papa’ battery – about the pattern of 59 Brigade behaviour after SAAF Mirage attacks. Fourie said everyone began emerging from their foxholes and relaxing about ten minutes after the last South African plane had gone. Franken timed an MRL ripple on 59 Brigade eleven minutes after an SAAF raid with devastating results. Franken’s growing reputation for craftiness had by now won him the nickname ‘The Jackal’.

By 23 October Colonel Ferreira was sufficiently confident that he had ‘fixed’ 59 and 21 Brigades to begin another major reorganisation of his force. He wanted to detach a substantial number of troops to move back to the Mavinga area to prepare for an SADF tank attack on 16 Brigade from the northeast. He also sent Commandant Jan Hougaard back to Rundu with a few specialist forces to prepare for a top-secret mission deep inside another part of Angola altogether.

★ ★ ★

Ferreira disbanded Task Force Delta and incorporated it into Robbie Hartslief ’s Combat Group Bravo, which consisted largely of 32 Battalion and 101 Battalion troops with support from UNITA units. However, a couple of 32 Battalion companies, including Piet van Zyl’s, were sent to Mavinga to be briefed for their new role in combination with the tanks.

Bok Smit’s Combat Group Alpha, consisting almost wholly of companies from 61 Mechanised Battalion, was also ordered to withdraw from the Mianei to Mavinga to be part of the big force being prepared for the attack on 16 Brigade. Combat Group Bravo would remain behind on the Mianei to protect the G-5s from 59 Brigade.

The coming phase of much heavier warfare required a new top-level command structure. Ferreira remained the officer commanding the 20 SA Brigade which, for some esoteric military reason, was renamed 10 Task Force, but which this book will continue to refer to as 20 Brigade. To allow Ferreira to concentrate on the job of warfare on the ground, a divisional structure was created with a senior brigadier, Fido Smit, coming in from Pretoria to liaise between the fighting forces at the sharp end and the brass and ribbons brigade sitting behind desks hundreds of kilometres away. Fido Smit, recognising Ferreira’s key role, established only an extremely modest divisional HQ on the Lomba River around a command Buffel stuffed with communications equipment.

As Bok Smit, Piet van Zyl and company prepared to pull out, the G-5s began redirecting their fire more towards Cuito Cuanavale after concentrating for many days on pounding 59 and 21 Brigades and the tactical group.

Adapting traditional Boer guerrilla deception tactics to air warfare, four Mirage F-1AZs sortied low and fast towards Cuito Cuanavale on the afternoon of Saturday 24 October. They had no intention whatsoever of braving Cuito Cuanavale’s formidable anti-aircraft defences to bomb the town. However, their simulated approach, deliberately ‘leaked’ by the SADF over its radio nets, brought Migs out of their reinforced concrete slit hangars at Cuito Cuanavale. As they taxied towards the end of the runway the G-5s at the Mianei began a full-force barrage and destroyed one Mig on the ground. Meanwhile, the F-1AZs had swung round and were racing back to Grootfontein and the pleasures of the golf course, cold draught beer, the pool tables and garlic calamari at Dan Louis’s restaurant.

Captain van Zyl admired how the artillerymen also used guerrilla tricks to fool Fapla Migs, searching for the G-5s, as to the big guns’ true positions. ‘There were 81 mm mortar groups operating with the G-5s,’ he said. ‘When word came that Migs were on the prowl, the mortars would fire from positions some distance from the G-5s with special shells which were aimed to land several hundred metres from the big guns. They exploded on impact with a flame and puff of smoke which closely resembled the recoil flash and fumes from the firing chamber of a G-5 after it had launched a shell. The G-5 teams sat drinking mugs of tea while they watched the Migs attack “their” positions. When possible, they used to warn the UNITA Stinger teams to get into position to fire at the Migs as the planes attacked the exploding mortar shells.’

One Stinger shot netted two valuable propaganda prizes on 24 October. Two Cubans baled out of a Mig-21 hit by a UNITA missile and were taken prisoner by Savimbi’s men. They were Lieutenant-Colonel Manuel Rocas Garcias and his co-pilot Captain Ramos Cacadas. The captain was newly arrived in Angola and was making his first sortie over enemy territory. Both men remained POWs for many months before being released in a big exchange of prisoners.

Within 72 hours of the G-5 team hitting the Migs on the ground at Cuito Cuanavale, the guns also destroyed two Hind-24 helicopter gunships as they prepared to take off from there. These bullseye shots were thanks to accurate information radioed back by 5 Reconnaissance Regiment commandos who had crossed the Cuito River and were ensconced in camouflaged ratholes within a short distance of the Cuito Cuanavale runway.

By Wednesday 28 October the Cuito Cuanavale airbase had been so comprehensively battered by the G-5s that it was no longer in use by Fapla jets or heavy transport planes.

The outstanding performance of the G-5s was a source of enormous pride to Colonel Jean Lausberg, the officer commanding the SADF artillery regiment in Angola.

Lausberg, based normally at the SADF School of Artillery in Potchefstroom, was celebrating his youngest daughter’s birthday in the first week of October at a wildlife lodge in the Kruger National Park when he received a wireless message to take over command of the artillery in Angola from Commandant Jan van der Westhuizen. The expanding scale of the SADF involvement required the presence in the field of a more senior officer. ‘I already had my kit packed,’ said Lausberg. All the top artillery officers were hoping they would be the ones ordered to see some real action.’

Having returned his family to Potchefstroom from their truncated holiday, Lausberg was in Rundu by 10 October. He took off in a Puma helicopter for the SADF brigade tactical HQ near Mavinga at 9 pm the same night. ‘We touched down at Mavinga at 11 pm. I had no idea where we were. I was completely disorientated.’ said Lausberg. ‘We had flown in total darkness at treetop height, and at Mavinga there was a complete blackout. I found somewhere to sleep under a bush and was woken in the morning by thousands of mopane flies buzzing around my head.

‘At that time 4 SAI was moving in from the Republic with the additional G-5 battery and the G-6 troop. It was a huge logistical task. In addition, there was a lot of reorganisation that needed to be done of all our artillery batteries. But the flies were driving me so mad that I couldn’t solve even comparatively simple problems, like how to get 4 SAI and 61 Mech gunners to their respective rearranged batteries. And my colleagues laughed when I complained that the mopane flies were even floating thick on the coffee I was served.’ Lausberg soon learned how to tolerate the mopane flies, stay sane and wage war at the same time.

‘By the end of October I had OPs (forward observers) all over the show,’ said Lausberg. ‘My gunners were receiving such a stream of information that they practically never slept. They were firing by day and by night. If something moved we would fire at it.’

The close relationship which had formed between UNITA and the CSI liaison teams also helped the gunners. ‘Commandant Les Rudman (of CSI) knew all the SADF radio frequencies, and on 19 October he contacted me on the regular artillery net,’ Lausberg recalled. ‘He said a UNITA recce at the Chambinga crossing could see lights approaching the bridge from the west. It was night. When I asked Les how he got the information he said he had a good radio man who had picked it up after it had been passed on through nine UNITA relay stations. So Les was the 10th and I was the 11th!

‘So I told Les, OK, but how do we direct fire onto the Chambinga bridge from the G-5s 30 km away south of the Mianei? He suggested that the UNITA man communicate through the 11 radio relay points how far the G-5 shells were landing north, south, east or west from the bridge. I didn’t have much faith in the idea, but I decided to give it a try.

‘I gave the fire orders and the crews reported: Ready. The UNITA recce reported that the first round had landed approximately 400 m northwest of the bridge. I gave the gunners a correction and the second round hit the bridge directly. Rudman said the recce was ecstatic but said the vehicles were still coming. It takes a G-5 shell between 60 and 90 seconds to travel 30 km, so through Rudman’s link-up we asked the UNITA man to tell us when vehicles were about 90 seconds from the bridge so we could hit it as one of them arrived. We caused a lot of problems that night, thanks to the UNITA recce and Rudman’s radio man. Later I gave Savimbi a special memento, a G-5 shell detonator fuse encased in perspex, to give to the guerrilla.’