Ferreira scheduled his attack for Monday 9 November. ‘Army chaplains came in to talk to the men before they went into battle,’ said Van Zyl. ‘Many of the guys were very apprehensive. They were national servicemen in their teens and most of them had never fought before, unlike Jurg, Thai and myself who had years of experience with 32 Battalion on and over the border.’

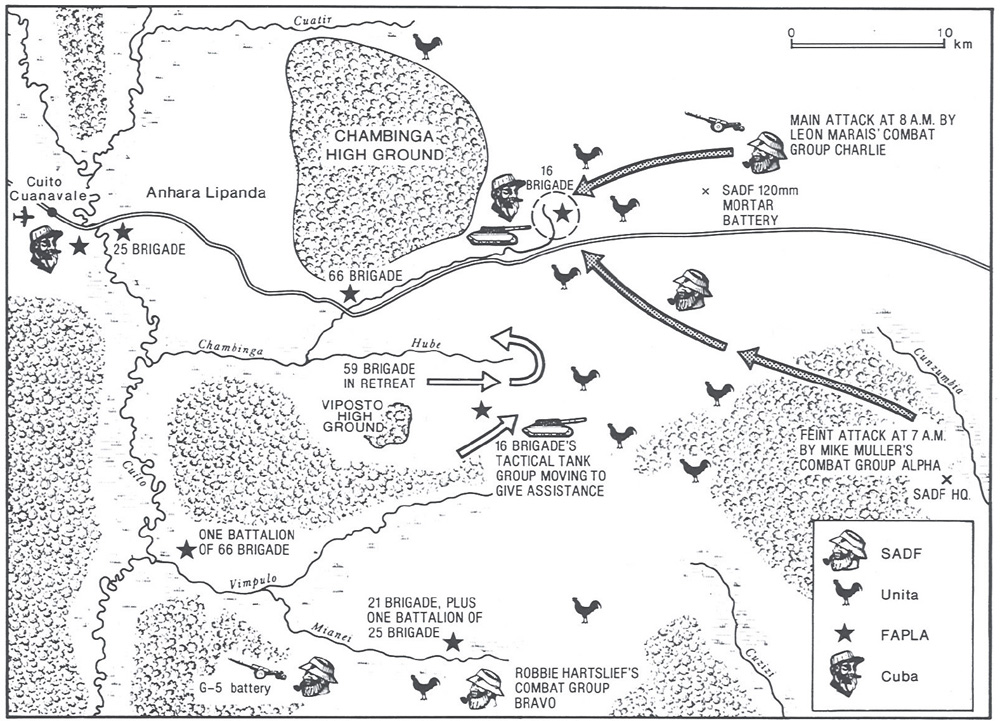

The combat groups began moving out on the evening of 8 November to be in position to strike the next morning. Combat Group Alpha, now led by 61 Mech’s new Commander Mike Muller instead of Bok Smit, who was totally exhausted from his efforts against 47 Brigade and had returned to the Republic to a new posting at Army College in Pretoria, was to make a feint attack from the southeast, the direction in which 16 Brigade’s defences were aligned. Then Combat Group Charlie was to launch the main attack from the north as soon as Mike Muller had broken contact. The Olifants were to lead Charlie’s attack, and after going right through 16 Brigade’s positions they were to push onwards to the source of the Hube and begin establishing a barrier across 59 and 21 Brigades’ lines of retreat.

Piet van Zyl’s company of 32 Battalion infantrymen – all black Angolans except for Van Zyl and four other white officers – was assigned to Combat Group Charlie. This time Van Zyl had less reason to fear that he would fail to see action. His company was assigned to walk in front of the combat group’s Ratels, locate 16 Brigade’s base area correctly, start the battle, and then let the armoured elements and mechanised infantry take over.

‘We moved 30 km west from the lagoon, riding in Ratels,’ said Van Zyl. ‘We passed the tank squadron and its support Ratels under the command of Major André Retief of 4 SAI. That man really knew how to look after his troops. He had brought a refrigerated canteen truck all the way from South Africa. We hadn’t seen a cold drink for months, so we organised a 32 Battalion guerrilla raid when the truck was unguarded and liberated the last two cases of chilled lager. Man, that was nectar from Heaven.’

Combat Group Charlie deployed about 15 km due north of the Chambinga source while the three G-6 guns (Juliet troop) moved into a position 15 km to the northeast of 16 Brigade, and was joined by the rejuvenated gunners of Quebec battery. Several artillery observers, recces and UNITA Special Forces had been sitting on high ground to the north and northwest of 16 Brigade for several days. Charlie’s commander, Commandant Leon Marais, was therefore confident that he knew 16 Brigade’s exact dispositions.

More than a hundred ‘Charlie’ vehicles then moved southwards towards the enemy before halting at 3 am on 9 November. ‘Sitting waiting inside the Ratels, everybody got tense, including myself,’ said Van Zyl. ‘I felt as though I was in a coffin and I kept remembering how many bits Captain “Mac” (Macallum) was in when they put him in a sugar bag after his Ratel-90 was knocked out by the T-55 on the Lomba.’

Combat Group Alpha moved up for six hours from its deployment area at the source of the Cuzizi before launching its feint attack at 7 am.

Combat Group Charlie crossed its start line at 4 am, eight kilometres north of 16 Brigade. At 5.30 am the G-5s, G-6s and 120 mm mortars launched a ten-minute ‘softening up’ barrage on 16 Brigade.

‘At about 6 am, when we were four km from the target, my company debussed from the Ratels to form a screen at the front with the two mechanised infantry companies behind, one to the left and the other to the right,’ said Van Zyl. ‘Next came the Ratel-90s and then the tanks with Ratel-20s and Ratel-ZT3s spread out between them.

‘In the kind of warfare I’d been used to, you stayed as quiet as leopards on the prowl. Here it was so noisy with all the vehicles behind that we felt like sitting ducks. Usually I felt in control of things: here I didn’t.’

The Attack on 16 Brigade, 9 November 1987.

At 6.30 am SAAF Mirage F-1AZs bombed 16 Brigade before Combat Group Alpha’s diversionary attack began. Mike Muller pounded 16 Brigade from a safe distance with mortars and the guns of the Ratel-90s. He also ordered his drivers to make as much vehicle noise as possible, revving up and changing gears, to divert attention from the approaching Combat Group Charlie. Then Muller broke off without any losses and moved rapidly four kilometres eastwards to lay up as a reserve force.

‘Our battle orders were straightforward – fight and win,’ said Van Zyl. ‘Some UNITA Special Forces had gone ahead of us, but we had lousy communications with them. My company was busy moving in on the left flank in a general south-southwest direction when a UNITA messenger came and said there were enemy tanks ahead on the left. I couldn’t believe it because Commandant Marais was so certain that all the enemy’s positions had been charted. I sent Vos (Lieutenant Tobias de Villiers Vos, one of Van Zyl’s platoon commanders) ahead to check out the UNITA intelligence and he came back and confirmed there were five tanks deployed to the left in an ambush position. We sent a message back to the Commandant and twice he responded: “Tanks? Are you sure?” He couldn’t believe it at first, but then he redirected a company of 4 SAI infantry in Ratel-20s and a squadron of Ratel-90s to take on the enemy tanks.’

Once the emergency attack force had redeployed the Olifants also swung out of line and moved up through the Ratels and infantry to lead the combined force. Within nine minutes of Marais ordering the action against the tank ambush, an Olifant had shot out the first enemy tank to fall to a South African tank since 1945 on the north Italian plains. The official 4 SAI log records that the T-55 was shot out by Lieutenant Hein Fourie, known to his friends as ‘Mieliepap’ (Maize Porridge), at 8.09 am on Monday 9 November 1987. Eight minutes later another T-55 had fallen to the Olifant of Lieutenant Abrie ‘Sirkusleeu’ (Circus Lion) Strauss.

The SADF tanks overran infantry positions at the ambush site, destroyed a BM-21 Stalin Organ and captured another intact. A Fapla soldier taken prisoner from one of the BM-21s confirmed that the main 16 Brigade base was still much further forward. A valuable map of Fapla minefields and defensive gun emplacements was captured. By the end of the engagement a third tank had been destroyed and two others captured intact; several trucks and a fuel tanker had been set ablaze; at least 20 Fapla lay dead and two had been taken prisoner. The South Africans lost no men or equipment, but by the time the last resistance had been mopped up and the ambush position cleared nearly two hours had been lost and several 16 Brigade units had escaped from the main position.

‘It took a long time for the Olifants to manoeuvre back into line from the flank,’ said Van Zyl. ‘My infantrymen were deployed 600 m ahead of the main force with a dozen Ratel-90s and Ratel-20s. They rode forward in the Ratel-20s before dismounting and fanning out on foot. Before the Olifants had got back into line properly we had walked into the perimeter of 16 Brigade’s base and they opened fire on us some time after 10 am with everything they had got – small arms, mortars, tanks. One of my black troops was killed instantly when a mortar shell burst among us and scattered heavy shrapnel. We pressed forward. The Ratels were behind us and we got really mad at them when they kept stopping because they thought we were stuck.

‘We crossed the first trenches and the Fapla infantrymen withdrew under our rifle fire and as we slung grenades. There was 23 mm fire coming in from somewhere which forced us to run all the time at a crouch.’

Meanwhile, the two companies of 4 SAI’s mechanised infantry which were meant to take over the fighting from Van Zyl’s men had run into difficulties. The 4 SAI company on the right (B Company) had problems in linking up with the forward Ratels because the thick bush restricted visibility more than had been anticipated. Smoke markers had to be used to indicate the boundaries of the company formation and this enabled Fapla artillery observers in the treetops to pin down the infantrymen by directing heavy mortar and 23 mm fire on them while they were still deploying. A Ratel-90 was badly damaged by 23 mm fire and the tailgunner was cut to pieces. An infantryman was killed by small-arms fire soon after he had dismounted from a Ratel-20. Another Ratel-20 was surprised by a T-55 which exploded unexpectedly from a particularly dense patch of bush. The Ratel gunner managed to slot a score of armour-piercing shells beneath the Soviet tank’s turret and it blew up. But a second T-55 appeared and slammed a 100 mm round into the Ratel, killing the gunner and the driver.

The 4 SAI company on the left (A Company) was quickly confronted by Fapla tanks. Immediately after the infantry dismounted from the Ratels a 120 mm mortar bomb fell among them, killing two men and wounding four.

Major André Retief moved his reserve troop of three Olifants across to the right to deal with the serious position in which B Company found itself. The Olifants came into contact almost immediately with the Fapla tanks and in the exchange of terrifying and tumultuous close fire a wheel and the track were shot off from one of the South African tanks. The tiffies went to work, shortening the track and linking it around the bogey and remaining wheels to enable the Olifant to limp back to safety under its own power.

The Olifant squadron found it difficult to manoeuvre according to plan in the dense bush. But, nevertheless, the action in support of A and B Companies ended with five T-54/55s destroyed and one T-55 captured in mint condition with only a few kilometres on the clock.

Piet van Zyl listened to the noise of battle behind him with increasing frustration. His men had overrun the first set of enemy trenches, but they could not advance without further support. They were pinned down in the trench system by small arms, mortar and 23 mm fire. Gradually, the weight of the firepower directed against them began to diminish as the SADF artillery observer travelling with the tanks began to direct fire from the distant G-6s on outlying 23 mm gun positions; as the Ratel-20 gunners began to dislodge Fapla snipers from the trees; and after Combat Group Charlie’s 120 mm mortar battery knocked out one of 16 Brigade’s own 120 mm mortar nests.

‘I wept with relief when André Retief arrived in his command Ratel accompanied by the first Olifant,’ said Van Zyl. ‘The rest of the tanks came through between our Ratel-90s and we regained momentum. Elements of 4 SAI’s two infantry companies began arriving and we all ran between the tanks tossing hand grenades into the trenches and bunkers to clear them.

‘Thai was running near me when he realised his platoon was no longer with him. He went back to find out what had happened. One of our ammunition vehicles was exploding and his men thought it was enemy infantry pinning them down. He got them moving again and soon we were passing burning enemy tanks. By early afternoon most of the Fapla infantry had pulled out. While our tanks pushed onwards we concentrated on clearing the battlefield. There wasn’t much fighting. There were only a few pockets of Fapla to deal with, but there was a lot of abandoned equipment that we had to collect together so that it could be removed. That wasn’t straightforward because Fapla Migs began coming in, occasionally quite low, and dropping bombs to cover 16 Brigade’s retreat. By late afternoon we were very tired and thirsty. We couldn’t get our wounded out in daylight, so the doctors were working hard keeping them alive until the casevac helicopters could fly in after sunset. I sent off Corporal Wessels to find our dead guy, because in my battalion we take every one of our men back home, dead or alive. Wessie couldn’t find the body, but he discovered that a UNITA group which had come in behind 4 SAI had buried him. I ordered the grave to be located. We dug him out, put him in a rubber body bag and moved him to the helicopter pad to be buried at home.

‘We needed to rest and regroup. But we couldn’t believe it when we got orders to pull all the way back to our original deployment area. I couldn’t understand it because I’d always been taught that in conventional warfare you continue to occupy ground you’ve taken.’

The Olifants meanwhile had moved on beyond the SADF infantry and by 2.30 pm were right through the 16 Brigade positions. But then, instead of pressing on to the Hube source, according to original plans, the tanks were ordered to pause and were later pulled right back to a laager area a few kilometres north of the battlefield.

Replenishment and repairs went on right through the night as military intelligence assessed the outcome of the battle. 16 Brigade had taken a heavy hammering. In the first encounter with the ambush group and the second inside the main enemy positions, Combat Group Charlie destroyed ten T-54/55s and captured three intact; captured one BM-21 and destroyed another; captured one 76 mm field gun and destroyed another; destroyed two 23 mm ZU-23 guns and captured a further two; and captured fourteen SA-7 and SA-14 anti-aircraft missiles, a 14.5 mm anti-aircraft gun and an 82 mm mortar. Three of the tanks were credited to the eight G-5s of the Sierra battery and the three G-6s of Juliet troop whose gunners fired 760 big 155 mm shells between them on 9 November. ‘The accuracy of our guns really surprised me,’ said Colonel Jean Lausberg. ‘The whole turret was thrown off one T-54. But what really helped us were the thin external fuel drums carried on the Soviet tanks because of logistics problems. If they were hit, the whole tank became a blazing inferno.’

In addition some 30 or so trucks were either destroyed or captured. These included 18 Brazilian Engesa trucks which fell into UNITA hands in one of the war’s many bizarre incidents. At the height of the day’s battle several trucks loaded with infantry drew up scarcely 100 m in front of Combat Group Charlie’s 120 mm battery. From the casual way in which the soldiers began dismounting and relaxing, the battery commander assumed they were UNITA soldiers who knew about his position. Headquarters then gave the commander a distant target on which to direct fire. The infantrymen, Fapla to a man, fled in panic as the first bombs hurtled high over their heads from the SADF mortar tubes. They left behind all their Brazilian vehicles. Several of the Fapla soldiers, who had been trying to manoeuvre northeastwards to launch a flank attack against Charlie, were killed or captured by UNITA troops protecting the mortar battery.

UNITA inherited the Engesas and much of the other equipment captured in the day’s fighting. Teams of guerrillas spent the night moving the spoils away to swell Savimbi’s big military inventory. The SADF hung on to some of the more sophisticated equipment, including the good-as-new T-55s, for delivery to Armscor. However, as an SADF driver moved one of the T-55s to the rear, he frightened the life out of a UNITA platoon who thought they were being attacked by the MPLA. The guerrillas raked the tank with machine-gun fire, trapping the driver inside until an SADF liaison officer was able to persuade them that it was a South African Soviet-built T-55.

Seventy-five Fapla dead were counted on the two battlefields and six were taken prisoner. Given the SADF’s loss of only seven men killed and two wounded, one Ratel destroyed, one Ratel badly damaged and one Olifant damaged, the inventory indicated a clear South African victory. But the fact is that the attack was a failure in terms of the objectives Colonel Deon Ferreira had set – the elimination of 16 Brigade and the cutting off of 59 and 21 Brigades so that they could be destroyed virtually at the SADF’s leisure.

16 Brigade, despite its heavy losses, escaped with the bulk of its men and equipment intact to fight again another day. Several Cubans escaped with two Cuban Army tanks which had not been committed to battle. The failure of Leon Marais’s Combat Group Charlie to close the Chambinga-Hube gap left open the getaway route to the Chambinga bridge for the Fapla brigades.

The decision to halt Combat Group Charlie’s advance proved to be one of the major mistakes and turning points in the war. It gave Fapla’s forces a reprieve which enabled them to reorganise and make life infinitely more difficult for the SADF than it would otherwise have been. It caused a huge row at Brigade level, with Colonel Ferreira particularly incensed by Commandant Marais’s decision not to press on to the source of the Hube. Subsequent political as well as military history might have been very different if 16, 59 and 21 Brigades, as well as 47 Brigade, had all been destroyed before the end of 1987.

Mitigating factors contributing to the unexplained decision not to press on with Combat Group Charlie to the Hube were: (a) the long hold-up caused by the unexpected tank ambush; (b) the fear of further losses of equipment and men by officers operating under the shadow of the impossible ‘lose no men, lose no equipment, achieve all your objectives’ philosophy; (c) the realisation on 9 November just how tardy the high command in Pretoria had been in releasing only 13 Olifants to take on several scores of Fapla tanks; (d) the unexpected aggressiveness of the T-54/55s and the unanticipated denseness of the bush; (e) the dented morale of many of the young national servicemen who, seeing battle for the first time that day, watched their comrades die terribly and grew up faster than they had dreamed.

★ ★ ★

‘That night Commandant Marais told us we would go straight back into the attack the next day (Tuesday 10 November),’ said Piet van Zyl. ‘To give us time to rest he scheduled the attack for mid-afternoon. But shortly after we moved off one of the 4 SAI guys shot himself in the stomach accidentally as he jumped from a Ratel during an air raid alert. He had to be operated upon on the spot, and by the time he was evacuated we had lost so much momentum that the attack was called off in case we ran into the same kind of problems as on the previous day.’

The attack was rescheduled for the morning of Wednesday 11 November. Meanwhile, throughout 10 November, the burden of keeping 16 Brigade busy fell on Juliet troop, Sierra battery and the neo-hedonists of Quebec battery, with their bloated stomachs, starched overalls and clean teeth and armpits. The 16 guns of Sierra and Quebec batteries between them fired 1,134 155 mm rounds on 10 November. With enemy Migs on constant prowl trying to seek out the big guns, the physical and emotional stress on the gun teams was especially great. And morale took a particularly grave knock that night when one of the gunners, sleeping next to a bush, was run over and killed by a truck bringing in food supplies.

This tragedy was a symptom of the growing strains on the SADF logistics system. Each G-5 battery had ten 10-tonne ammunition trucks attached to it; but between them the trucks could only carry 960 shells and propulsion packs. The batteries also needed copious supplies of fuel, water and food, especially during major battles. It was not only the G-5 batteries which needed resupplying. The Papa battery of MRLs, for example, fired more than 1,000 127 mm rockets on 10 November from south of the Mianei. ‘Every night before and during the battle with 16 Brigade transport aircraft were landing at Mavinga with G-5 and MRL projectiles,’ said Jean Lausberg. ‘The record was four ammunition landings in one night. A C-130 could bring in 100 projectiles at a time, but when our guns were firing rapidly it was never enough should the pressure stay heavy for a prolonged period. It was a very difficult logistics situation. We also ran high security risks because at the height of battle we had to give all our latest logistics demands to Rundu by high-frequency radio.’

The SADF intensive use of forward observers inside enemy lines again proved invaluable to the artillery in acquiring targets on 10 November. ‘We had one observer, Major Cassie van der Merwe, protected by recces from 5 Reconnaissance Commando, at Candonga, part of the Chambinga High Ground rising to nearly 1,300 m immediately north of the source of the Chambinga River,’ said Lausberg. ‘Cassie said he had spotted a BM-21 Stalin Organ, two T-54 tanks and a logistics vehicle all camouflaged within a triangle some 600 by 600 by 600 m,’ said Lausberg. ‘Troops were spread out and resting throughout the triangle. I went to our military intelligence people for their appreciation. They said they were sure there was a lot more equipment inside the triangle than Cassie had been able to spot. We requested an Air Force attack. When it was turned down, Cassie started bringing down G-5 fire from Quebec battery which was positioned at the source of the Cuzizi. We did a lot of damage there.’

★ ★ ★

By the time the SADF was ready to resume its attack on the morning of 11 November, 16 Brigade had redeployed in two groups – the strongest immediately south of the Chambinga source, and the other directly east of the Hube source with tanks of 16 Brigade’s tactical group moving rapidly north from the Mianei area to join up again. Intelligence reported that 16 Brigade was expecting the next SADF attack to come from a northeast direction. Marais therefore decided to re-deploy Combat Group Charlie southwards, scissoring behind Combat Group Alpha as Mike Muller launched yet another feint attack from due east. Charlie would then swing through a sharp fish-hook curve to strike at 16 Brigade from the south.

The tactics were good and they might have had excellent results if, at last, everything had begun to go according to the plans outlined on the scale models made in sand on the Angolan forest floor. But from the start there were delays and the day’s timetable kept getting put back. The early hold-ups were caused again by the unexpected thickness of the bush, with the armour officers unable to see ahead much more than 20 metres. It took longer than expected for Charlie to cross behind Alpha, whose commander ordered as much engine-roar as possible from his drivers to drown out the noise of Charlie’s subterfuge. Muller’s feint attack was delayed several times waiting for Charlie to cross behind him, but finally his force went in and came out smoothly without loss. Charlie meanwhile had run into even thicker bush, and an attack by two Mig-23s in which a 4 SAI soldier received shrapnel wounds meant that all element of surprise had been lost. Small Fapla infantry teams then located Charlie which came under intermittent small-arms fire.

The bush became yet thicker with visibility down to five metres and the Mig-23s returned again to bomb the force. Combat Group Charlie finally arrived at its first target, at the source of the Hube, more than two hours behind schedule only to find that the Fapla force there had already withdrawn westwards. Edgy SADF infantrymen, seeing movement on top of a vehicle knocked out in an early morning bombardment by the G-5s, began shooting only to realise they were attacking a troop of resident baboons who gave a first-class demonstration of how to retreat under fire at top speed.

‘It was a very difficult day for the infantry commanders,’ said Piet van Zyl. ‘It was long, tense and tiring for the men. Early on I conserved my men’s energy by putting them in the Ratels while Vos and I took others up on top of the tanks for the ride. After we passed the first objective we still had a long way to go northwards to the second. Nevertheless, we ordered more of the men to walk so that they were fully alert. The 32 Battalion boys began to take it in turns with the 4 SAI guys to fan out on foot in front. By now there were Mig-21s and Mig-23s circling above almost constantly and our anti-aircraft people were shooting with everything they had to keep the planes high. The bombs came zooming down but were inaccurate.’

As the long day dragged on the foot soldiers got more and more careless. ‘When we approached one particularly thick piece of bush someone started firing into it unprovoked,’ said Van Zyl. ‘The next moment nearly everybody was letting loose. We had a hell of a job to get them to stop.

‘Major Retief told Commandant Marais it was essential for the infantry to have a short rest. By then it was about 2 pm and they had been on the move for nearly ten hours since Charlie moved out of the overnight laager at 4 am. Marais agreed. The Ratel crews got out of their vehicles and lounged in the grass with the infantry. I was stretched out on the back of an Olifant.

‘What we didn’t know was that we had stopped right in the centre of 16 Brigade’s arc of defensive fire. Suddenly they opened up with everything they had – mortars, field guns, anti-aircraft weapons, sniper rifles, rockets. Bullets and shells were shredding the trees and making sawdust of them as I leapt from the tank. Two of my guys were killed when a mortar shell fell on the turret of the Olifant on which they were resting. Another was seriously wounded when he was hit by a 14.5 mm shell.

‘When I got my feet on the ground I worked with Vos to get our guys to link up with the 4 SAI infantrymen. Major Retief, commanding from a Ratel-20, got his Olifants organised with amazing speed. They started a fire belt action (a firing pattern in which every tank fires simultaneously). That gave us a slight breathing space but I could see some of our Ratel-20s burning which had been shot out by Fapla tanks.’

Seven infantrymen were hit by treetop snipers in those early minutes before the threat could be eliminated. A tank commander was also wounded and evacuated. Meanwhile, the EW teams began to pick up more bad news. Military Intelligence had estimated that Fapla had gathered 22 tanks with 16 Brigade at the Chambinga source. Now it seemed, according to the EW men, there were three separate groups of tanks together totalling more than 30. Charlie could no longer predict from what direction a tank charge might suddenly erupt.

Commandant Marais, Major Retief, Captain van Zyl and other officers reorganised the force and got it moving forward again in reasonable order. The lead Ratels soon ran into Fapla’s infantry fire and then the first of the enemy tanks emerged into the open. ‘As we moved forward we could see the T-55 moving towards us,’ said Van Zyl. ‘The next moment it was spewing smoke and it came to a standstill. As the crew jumped out the men in my platoon shot every one of them dead.’

Van Zyl thought the T-55 had been shot out by an Olifant. In fact, it was a Ratel-20. 4 SAI Rifleman M J Mitton, the Ratel gunner, found himself facing the T-55. He fed a belt of armour-piercing shells into his 20 mm cannon and began spitting the projectiles towards the T-55 at a rate of 12 per second until the tank began to smoke. Mitton had just enough time to send the message ‘T-55 visual. Eliminated’ to Major Retief’s radio operator before a second T-55 loomed behind the first and sent a 100 mm shell ripping through the Ratel’s small observation window, killing the driver instantly and seriously wounding Mitton and another crew member. Mitton elevated his cannon to allow the driver to escape through his hatch, not knowing that his comrade was in several pieces. Mitton then scrambled out of his own hatch and fell exhausted from the vehicle. His buddies pulled him clear of the burning Ratel but he died later from his injuries.

Follow-up Attack on 16 Brigade, 11 November 1987.

Despite its losses, Combat Group Charlie now had 16 Brigade on the run, with the 4 SAI and 32 Battalion infantry advancing steadily and occupying abandoned Fapla trenches. The Olifants moved through to take the initiative but instead ran into a minefield. It was marked on SADF maps, but as the adrenalin pumped in the heat of battle some of the tank drivers moved forgetfully into the minefield and Abrie Strauss’s Olifant detonated a mine which blew off one of the steel tracks and severely damaged the suspension. A Ratel also detonated a mine and the driver was killed when an enemy tank shot out his stranded vehicle.

‘All the infantry people were psyched up and were prepared to go through the minefield,’ said Van Zyl. ‘So we called for the plofadders and fired two of them, but neither detonated. Next we tried to send some Ratel-90s on a flank attack with a group of 32 Battalion infantry led by Jeug Human. But they ran into Claymore and anti-personnel mines. It was bloody frustrating.’

[A plofadder is a long sausage-like string of explosive weighing 500 kgs which is fired by rocket over the minefield from a specially adapted Casspir vehicle. The plofadder detonates automatically, exploding and throwing aside mines for several metres on either side of it, thus clearing a safe path through the minefield. The plofadder was still at the experimental stage of development in South Africa and this was the first attempt at using it in battle.]

Several tanks had avoided the minefield and others had got through it unscathed. Retief lined them up in front of the minefield to lay down a protective field of fire while three tiffies went into the field in an armoured recovery vehicle (ARV) to rescue the badly damaged Olifant. It was a perilous task with bullets clunking from the armour all the time and mortar shells falling into the minefield and exploding at intervals. Retief became worried when no one emerged from the ARV after it had manoeuvred close to the Olifant and remained motionless for some time. He radioed Van Zyl to say he needed volunteers to go into the minefield and help with the Olifant recovery. Lieutenant Tobias de Villiers Vos volunteered and Van Zyl went with him.

‘There was noise and chaos all around, but we reached the ARV,’ said Van Zyl. ‘There was huge relief all over the faces of the tiffies when they looked out and saw Vos standing there on the outside getting to work on hitching the tank up to the ARV’s winch. Eventually one of them got out to help Vos. The vehicle’s cab is very high and you are very vulnerable as you exit. The damaged tank track was jammed and the pair of them had to climb back to the top of the ARV, with bullets thudding around them, to get the cutting gear. They freed the track so that it would rotate, but the ARV couldn’t pull the tank out of the clogging sand by itself. Another ARV and an Olifant had to be called in to tow it to safety where it could be repaired.’

[For his courage in crossing the minefield and taking the initiative in recovering the Olifant, Lieutenant de Villiers Vos was later decorated for courage on the field of battle with the Honoris Crux.]

While giving cover to the minefield rescuers the Olifant crews watched in astonishment as one Fapla commander, whose T-54 had been hit in its tracks, climbed out of the hatch and then sedately reached back to reemerge clutching a smart briefcase before strolling off with it under his arm as unflappably as a business executive going to the office. He was shot dead as he ambled away from his crippled tank. The Olifants had by now destroyed another two enemy tanks. Several other units had got forward to support the Olifants, including two platoons of 32 Battalion who, along with 4 SAI infantrymen, captured a line of trenches from which Fapla infantrymen had been firing intensively.

The momentum, lost when the Olifant got stuck in the minefield, was beginning to be regained when Major Retief ordered a retreat. Several things concerned him. Although Fapla infantry resistance was fading, the SADF infantry companies were running low on ammunition and they were separated from fresh supplies by the minefield. As its infantry withdrew Fapla began to concentrate heavy artillery fire on the South Africans. Retief also feared that an enemy air attack might catch his Olifants exposed in front of the minefield – and Olifants were not to be lost in any circumstances, the high command had made that very clear!

‘Our infantry were very upset at being ordered to withdraw,’ Van Zyl asserted. ‘One of the 4 SAI corporals said he wouldn’t retreat and they had to read the riot act to him before he obeyed. Personally, I think if we had fought on we’d have got 16 Brigade’s base. By withdrawing we let them know that minefields hassled us. And they didn’t forget it either.’

When Piet van Zyl’s 32 Battalion men had withdrawn to the ‘safe’ southern side of the minefield he gathered his platoon leaders – Theron, Human, Wessels and De Villiers Vos – for reports on the state of his company. ‘Besides those we knew to be dead, there were eight black soldiers missing,’ he said. ‘I went back with Vos looking for our lost people who had been in the thick of the fight with the Fapla infantry. We gathered up seven of them... They were OK. But when Major Retief gave the final order to complete the pullout there was still one missing. A 4 SAI guy came back who said he had seen a 32 Battalion soldier sprawled out in one of the Fapla trenches; he appeared to be dead.

‘I told Retief I would have to recover the soldier. The Major said it was impossible. The retreat could not be delayed any further. I told him I couldn’t leave until the missing guy had been recovered.’ Another officer present at the time takes up the story: ‘De Villiers Vos volunteered to go back with Piet. It was highly dramatic. They had to run forward 800 m, first crossing the minefield and then leaping into the forward Fapla trenches, all the time under rifle and machine-gun fire from remaining pockets of Fapla infantry. Vos would first sprint forward a few metres with Piet lying flat and giving him covering R-4 rifle fire. Then Vos would fling himself flat and give Piet cover as he ran forward for a few metres like a bat out of hell. Then it was Vos’s turn to run again. They leap-frogged forward in this fashion all the way to the Fapla trenches where they engaged enemy infantry in a firefight while we all looked on in amazement as though watching a war movie.

‘They found the soldier in the trench system. He was alive, but had a serious back wound made by a 14.5 mm shell. They made a stretcher for him with their rifles and a ground sheet and then started running back. They had made 200 m before one of the Ratels moved into the minefield to pick them all up under a belt of covering fire from the Olifants. They made it to safety and then we all got the hell out.’

Mike Muller’s Combat Group Alpha was ordered into the fray to take over from where Leon Marais’s Combat Group Charlie had left off. Muller’s Ratels and infantrymen were to marry with the Olifant squadron. But Alpha was never really clear about its task, and the late notice meant that it was able to begin the attack only an hour before sunset, by when Fapla had broken contact and pursuit was inadvisable because of the thickness of the bush. Muller was therefore ordered to withdraw, along with Charlie, to rear laager areas.

Intelligence showed that more than 300 Fapla had been killed or wounded in that day’s action and 14 enemy tanks had been put out of action. This compared with five South African dead, 19 wounded, one tank crippled and several Ratels lost – a clear victory by any numbers game. But again the action had to be judged a failure. 16 Brigade, despite its terrible casualties and severe equipment losses, still had not been destroyed and the Hube-Chambinga gap to safety for the Fapla brigades remained open. The SADF top brass went back into planning sessions to decide on an emergency plan to plug the escape hole.

Charlie’s woes were not over, even as its weary fighters withdrew in darkness to its laager after getting the wounded to the field hospital.

‘The supply convoys were rumbling in from the rear echelon to enable us to reorganise and refuel,’ said Van Zyl. ‘Officers got little sleep as the choppers and fuel lorries came in all through the night. Exhausted infantrymen and tank crews were sleeping on the forest floor around the tanks and Ratels. As the logistics vehicles came in they were meant to have someone walking in front of them to watch out for sleeping soldiers. But the system went wrong, and one supply truck ran over a tankman, who had survived two days of battle with T-55s, and smashed both of his legs. He joined the wounded being casevaced out by the choppers. His war was over.’