Sugar cane is a member of the grass family. In botanical language it is Saccharum officinarum, a name given to it by Linnaeus himself—Carl von Linné, the inventor of our modern classification system. This, and five related Saccharum species, are placed in the Andropogoneae tribe, along with sorghum and maize. Like other grasses, sugar cane has jointed stems and sheathing leaf bases, with the leaves, shoots and roots all coming from the stem joints.

The world’s scriptures have few references to sugar. Sugar rates no mention in the Quran (which, as we will see later, is significant), and while both Isaiah 43:24 and Jeremiah 6:20 refer to ‘sweet cane’, which some people think might mean sugar cane, there are a number of other candidates. If we assume that sugar was intended where the Bible’s translators wrote of ‘sweet cane’, then the line in Jeremiah, ‘To what purpose cometh there to me incense from Sheba, and the sweet cane from a far country?’, tells us that sugar cane did not grow around Palestine in Old Testament times. The problem here, as ever, is that we are in the hands of translators who interpreted the Old Testament in terms of their own understandings and assumptions about the past.

The only world religious leader who makes any specific reference to sugar is Gautama Buddha. His words were written down some time after his death, so there may have been some interpolations, but he was probably familiar with at least some form of sugar cane. Buddha was, after all, born about 568 BC, at a time when the sugar cane was probably known and grown in India.

The set of instructions known collectively as the Buddhist rule of life, the Pratimoksha, defines pakittiya or self-indulgence as seeking delicacies such as ghee, butter, oil, honey, fish, flesh, milk curds or gur (a form of sugar) when one is not sick. As this particular rule was laid down by Buddha himself, it suggests he was at least aware of sugar. As well, when Buddha was asked to allow women to enter an order of nuns, he likened women in religion to the disease manjitthika (literally, ‘madder-colour’, after the red dye called madder) which destroys ripe cane fields, and which is caused by Colletotrichum falcatum. This fungal disease of cane still exists, going by the common name red rot.

There are other Indian references to sugar from this period, but the exact sort of sugar meant is never clear. Still, it seems there were cane crops large enough to suffer disease in Buddha’s time, around 550 BC, and a Persian military expedition in 510 BC certainly saw sugar cane growing in India. The army of Alexander the Great reached India around 325 BC, and Nearchus, one of Alexander’s generals, wrote later of how ‘a reed in India brings forth honey without the help of bees, from which an intoxicating drink is made though the plant bears no fruit’. We now take this to mean that he saw sugar cane and sugar juice, but not sugar itself. This comment has often been used to argue that sugar cane was taken to Egypt by Alexander at about this time, but there is no evidence for that.

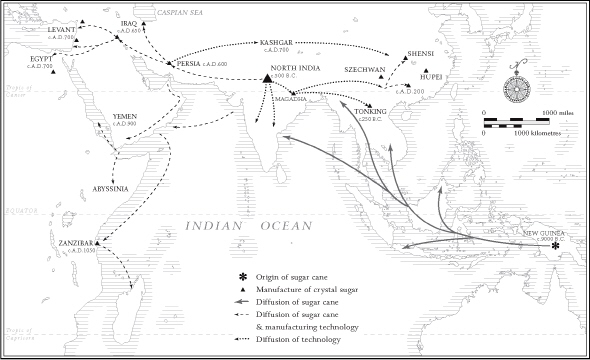

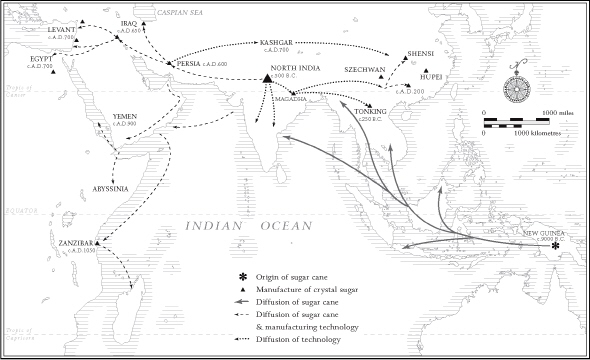

The spread of sugar before it reached the Europeans.

Around 320 BC, a government official in India recorded five distinct kinds of sugar, including three significant names: guda, khanda (which is the origin of today’s ‘candy’) and sarkara. If the date is correct, this would appear to be evidence that sugar was being converted into solids in some way before 300 BC, so perhaps Nearchus did see sugar after all. Remember the guda and sarkara, because we will meet them again.

By about 200 BC sugar cane was well known in China, although it is possible that it was only chewed as cane. There is a record from AD 286 of the Kingdom of Funan (probably Cambodia) sending sugar cane as a tribute to China. Some 500 years earlier, in the late part of the Chou dynasty, it was recorded that sugar cane was widespread in Indochina. It is also possible that sugar cane was being grown at Beijing around 100 BC, though it is hard to tell how successful this would have been, 40 degrees north of the equator. We do know that sugar cane was already on the move, and could have reached Africa at about this time, and perhaps Oman and Arabia. The important move of sugar (as opposed to sugar cane) onto the world stage seems not to have come until around AD 600, when the cultivation of sugar cane and the art of sugar making was definitely known in Persia, at least to the Nestorian Christians who lived there.

Sugar cane was an important crop in India long before this, and nobody seems to know quite why it took so long to reach Persia (modern Iran). Perhaps it has to do with the irrigation that the cane needs in dry areas. In AD 262, Shapur I, a Sassanid king, made a dam at Tuster on the Karun (Little Tigris) River in Persia to irrigate surrounding areas by gravity feed relying on the height of the waters behind the dam. The water was eventually used to irrigate cane, and the ruins of the irrigation works are still there.

The centralised system of authority that was the Persian empire would have allowed the development of large-scale irrigation schemes. Major irrigation schemes anywhere, like the terraced rice fields of Java and Bali, the fields along the Nile and Australia’s irrigation areas, all rely on a central authority to provide organisation and an imposed peace.

A community of Nestorian Christians was certainly making good sugar in Persia around AD 600. If the art of sugar making had now been perfected, this could explain why sugar suddenly took off. The crop and its product had only spread slowly up until then, so clearly something happened: either there was a change in the method of growing cane or in the methods of extracting sugar, or maybe there was a change in the nature of the cane. Then again, as many writers have suggested in the past, perhaps sugar just followed the spread of Islam, once Islamic forces had defeated the Sassanid dynasty of Persia.

THE TRUE INVENTORS OF SUGAR?

All over the world, the word for sugar seems to come from the Sanskrit shakkara, which means ‘granular material’. We find words like the Arabic sakkar, the Turkish sheker, the Italian zucchero, the Spanish azúcar, the French sucre and, of course, the English ‘sugar’. It is sukker in Danish and Norwegian, sykur in Icelandic, socker in Swedish, suiker in Dutch and zucker in German. Yoruba speakers in Nigeria call it suga, Swahili East Africa calls it sukari, Russians call it sachar, Romanians say zahar and the Welsh call it siwgwr—and when you allow for the Welsh pronunciation of ‘w’ (rather like ‘oo’ in ‘book’), the pattern is retained.

Bahasa Indonesia is one of the few languages where this pattern does not apply. Here, the name for sugar is gula, although when biochemists in Indonesia speak of ‘sugars’ as a group the name they give them is sakar. The Arabic origins of that are clear enough, but that expert among experts on Malay etymology, R. O. Winstedt, said in his early twentieth-century dictionary of the Malay language that he could see the Sanskrit origins of gula just as easily. But he said so without knowing that sugar cane originated on the island of New Guinea, at the far end of the Indonesian archipelago. Tradition then had it that sugar cane originated in India or China, and Winstedt was an old man when its true origins were worked out.

Few Europeans know much of the immense Hindu influence on Java and Bali. The various Javanese empires traded with India over many centuries, and perhaps sugar in a prepared form was first traded to India from Java, not the other way around. In that case, when the art of sugar making was learned in India, a Sanskrit word similar to the established Indonesian word would have been applied to the product the Javanese knew as gula. So gula would have given its name to the Indian gur, rather than the other way around.

Why would the Indians call it gur? The European linguists say the sugar came out of the boiling-pan as a sticky, treacly ball, and gur is a Sanskrit word for a ball. All the other lands heard about sugar as shakkara. Why would Indonesia alone have a different name for sugar, unless it was their word to begin with?

Perhaps the Indians who brought the Hindu religion to Java came from a place where gur or gula or even guda was used in preference to shakkara, but it would be unfair to rule out an Indonesian origin for the first refining of sugar to crystals. Bronze drums were well known in the archipelago, and ironware could have been traded there quite early on, so an Indonesian origin of sugar is at least possible.

I admit this is speculation, and the question has to remain an open one. The earliest records of sugar crystals seem to come from India, where a Sanskrit manuscript dating from about AD 375 refers to sito sarkara churna, but this ‘powdered white sugar’ may have been formed simply by drying gur. Manuscripts from that period are hard to date, but certainly by the fifth century AD, and quite possibly much earlier, we seem to see the first descriptions in Sanskrit of the preparation of sugar as we know it from cane. On the other hand, old manuscripts only rarely survive, so who can say what Indonesian records are missing?

THE SACKING OF DASTAGERD

The year AD 622 was a key year for three religions: the growing Islam under its prophet Muhammad, the Zoroastrianism of the Persians under the Emperor Chosroes II, and the Christianity of Byzantine Rome, based in Constantinople where Heraclius was emperor. Chosroes held the upper hand, and when an unknown Meccan sent him a letter, calling upon him to acknowledge Muhammad as the apostle of God, Chosroes rejected the invitation and tore the epistle to pieces. He had the Roman Empire on the run; what need had he of such an upstart as Muhammad, who called himself Prophet?

A bit of background: Phokas, Emperor of Byzantium AD 602– 610, had been deposed by Heraclius, and Byzantium was tottering. A group called the Avars was attacking the European part of the Roman Empire. Chosroes was quietly taking Asia Minor, bit by bit, using the pretext that he was avenging Maurice, who had been deposed and murdered by Phokas.

This vengeance claim rang a little hollow once Heraclius took the throne from Phokas, but Chosroes already held Syria when Heraclius was crowned, and he continued to advance in the name of Zoroastrianism—with Jewish, Nestorian and Jacobite Christian allies. In short, the Middle East in the seventh century was as troubled as it is in the twenty-first century.

In 615, when Chosroes held most of the Middle East, Muhammad predicted in the 30th surah of the Quran, called Ar-Rum (‘The Greeks’), that the forces of Byzantium (known to Muhammad as the Greeks) would be victorious over Persia. At the time this was a daring and improbable claim, for just a year earlier Chosroes had written scornfully to Heraclius from Jerusalem: ‘From Chosroes, the greatest of all gods, the master of the whole world: To Heraclius, his most wretched and most stupid servant: you say that you have trust in your Lord. Why didn’t then your Lord save Jerusalem from me?’ The future for Byzantium was looking bleak.

When Muhammad moved to Medina in 622, Heraclius was just setting out on a series of campaigns that paradoxically would open the way for Islam to advance. The Roman emperor led his troops on 48-mile marches in 24 hours, out-fought and out-thought the Persians and tore apart their empire. He forced Chosroes into defeat after defeat and retreat after retreat, until in 627 Chosroes was deposed, to ‘die in a dungeon’ five days later, after seeing his eighteen sons killed. Peace was made and Rome regained all of its lost territory. Heraclius was freed at last of the burdens of war, but the two mutually weakened empires were ready to be taken over by forces which flocked to the once-obscure Meccan upstart. Byzantium and Persia had worn each other out and, in the last eight years of his rule, Heraclius saw all of his regained provinces fall to the Arabs.

When Chosroes fled his royal palace at Dastagerd, the Roman forces found extremely fine pickings. Among the loot they found aloe wood, pepper, silk, ginger and sugar, described as ‘an Indian delicacy’—which by then it almost certainly was not. All the same, this is an important clue, because it suggests that while sugar making might have been unknown beyond the Persian empire, sugar itself had been heard of, and seen.

Islam gained substantially from the Byzantium–Persia conflict, because the successful Quranic predictions like the one in ‘The Greeks’ were hailed as evidence that Muhammad was a true prophet. This gave Islam a dominant position in the Arab world, and it was now free to move into the power vacuum. Islam was on the move, and right in its path lay the places in Persia where sugar was being prepared by Nestorian Christians. Soon after, the Muslims would acquire many other areas where sugar cane would grow.

THE WANDERING SUGAR CANE

This foray into Middle Eastern history has taken the story slightly ahead of itself, however. From its early beginnings as a crop for chewing and sucking on, the sugar cane had spread first with coastal traders. The people of South-East Asia and the islands, like their Polynesian descendants, were excellent navigators, launching themselves out into the Pacific on trading journeys 4000 years ago. These people all speak languages of the Austronesian group, and they probably originated somewhere around Taiwan before spreading as far as Easter Island, New Zealand, Fiji, Hawaii, Tahiti, Indonesia and the Philippines, and all the way across the Indian Ocean to Madagascar.

We know where the early seafarers went in the western Pacific, because we find the signs of their travels in remnants of obsidian, a volcanic glass carried from New Britain to New Ireland some 15 000 or 20 000 years ago. They left adzes, used for making dugout canoes, at sites which appear to be 13 000 years old. Three thousand years ago, New Britain obsidian was travelling as far as Sabah in north Borneo. Then there are the marsupials that were taken from New Guinea, and perhaps Halmahera, to stock small islands, presumably for hunting purposes. The archaeological record shows the sudden appearance of both cuscuses (cat-sized nocturnal possums) and wallabies on the island of Gebe 10 000 years ago. But at least 30 000 years earlier, humans made sea crossings beyond any sight of land, as the first people travelled to Australia. Even when the Ice Age had lowered sea levels 100 metres or more, the crossings were still daunting.

English speakers and Europeans in general rarely know that Asia and the Pacific had brave and skilled seafarers long before the time of Leif Eiriksson. They have no idea that Chinese fleets visited East Africa before Vasco da Gama entered the Indian Ocean, or that giant bronze drums made by the lost wax method at Dongson, close to Hanoi, were carried to places like Bali well before the Christian era, as traders slipped from island to island, crept around coasts, and occasionally used seasonal winds to make longer ocean crossings. And at some stage, somewhere along the way, these seafarers carried sugar cane to wherever it would grow. Only later did it spread to Persia, the Mediterranean and across the Atlantic.

Taxation records clearly show taxes imposed between AD 636 and AD 644 on sugar grown in Mesopotamia. The sugar captured at Dastagerd in 627 had probably originated in Persia, but it was still an Indian product as far as most people were concerned. That was about to change, however. In 632 the prophet Muhammad died, and soon afterward the forces of Islam commenced their amazing expansion. In 637 the Persians were defeated at Kadysia, which meant the final collapse of the Sassanid empire, and now the Muslim forces were in a position to discover sugar (as opposed to sugar cane) for themselves.

Certainly we can reject the legend that Marco Polo brought the art of sugar refining back from the east in the thirteenth century, because he commented on the similarities between the Chinese and Egyptian methods of making sugar. All we can say for certain is that sugar cane came from New Guinea, was traded along a variety of coasts, spread inland, hybridised with other species in India and travelled some more, and that somewhere between Indonesia and Persia, about 1500 years ago, somebody discovered how to make sugar from the juice of the sugar cane. From that point, sugar and the technology it demanded began to travel, and as the technology spread it started changing things. Garden cane for chewing could spread by simple diffusion, but the idea of sugar technology was different, because people were able to carry that across continents and oceans. It was an idea as much as a crop.

Wherever it was encountered, sugar was highly valued. It is hardly surprising that Columbus took sugar cane to the West Indies or that the First Fleet carried sugar cane from the Cape of Good Hope to Australia. Later, when refined sugar reached New Guinea, it was named siuga in Pidgin English. Sugar had come all the way back home, but along the way it had changed remarkably, from a sticky sweet sap sucked from the cane to pure white crystals in paper bags.

More to the point, by the time sugar came home again it had helped change the world. It had proved a troublesome crop—it had made fortunes, caused rebellions, battles and bloodshed, made and broken empires, led to the enslavement and death of millions and, in the process, to the transplanting of blocks of humanity around the world, taking 20 million Africans to the Americas, Japanese and Chinese to Hawaii, Indians to the West Indies, the Pacific, Mauritius and Natal in South Africa, and Pacific Islanders to Australia, all in the interests of making other people rich.

FLATHONYS

Take mylke, and yolks of egges and ale, and draw hem thorgh a straynour, with white sugur or black; and melt faire butter, and put thereto salt, and make faire coffyns, and put hem into a Nowne till þei be a little hard;.þen take a pile, and a dish fastened thereon, and fill þe coffyns therewith of the seid stuffs and late hem bake while. And þen take hem oute and serue hem forthe, and caste Sugur ynough on hem.

Harleian ms 279: fifteenth-century cookbook