4

THE ENGLISH

AND THE SUGAR

BUSINESS

Spain and Portugal were the first nations to begin serious exploration, and the first to start laying serious claims to new territories outside Europe. After 1493 they had the authority of the Treaty of Tordesillas to back their claims, and the Portuguese promptly claimed Africa as their own, but the other nations of Europe were unimpressed. In this treaty, Pope Alexander VI specified a line from Pole to Pole passing through a point west of the Cape Verde Islands at about 50 degrees west of Greenwich. This line assigned perpetual ownership, to either Brazil or Spain, of all new lands that were found, anywhere in the world.

In 1529 the Treaty of Zaragoza (or Saragossa) added a further dividing line at about 145 degrees east, completing the division of the globe into Spanish and Portuguese hemispheres, and gave the Philippines to Spain. By the end of the sixteenth century, however, there were Protestants around who cared little for rules made by a Pope, and even Queen Mary could not get her Privy Council to endorse the treaty. Loyalty to nation and profit took precedence over any religious loyalties.

In fact, about the only time that the British, French or Dutch recognised the treaty line was when they argued that European peace treaties had no force beyond the line. In other words, when it suited them the line was there, but at other times it evaporated, and there was ‘no peace beyond the line’.

So in Queen Mary’s time, the Privy Council gravely forbade African expeditions. They did their duty by saying that much, and the English ships continued to sail. The English knew that even the Catholic French took no notice of the treaty. As far back as 1523, when a French captain called Jean the Florentine had led an attack on a Spanish treasure ship, and King Charles I of Spain had protested over it, King Francis II of France had answered, ‘Show me the testament of our father Adam, where all these lands were assigned to your Majesty.’

If there was no problem playing tricks on the Dons under Catholic Queen Mary, there was firm if subtle encouragement once Protestant Queen Elizabeth was on the throne. Thus her Privy Council also told the sailors not to go, and then winked at them as they sailed off. Even if Spanish and Portuguese spies knew all this, there was little they could do, what with the French Calvinists having a colony at Fort Coligny in what is now Brazil, the Portuguese and Dutch squabbling over the Spice Islands and much else as well, not to mention the Dutch, the English, and even the Danes, all poised to join in and take a share of the Spanish–Portuguese cake—and all of those countries got their share of sugar as well.

The German lawyer Paul Hentzner visited London in 1598. He tells us of his visit that:

. . . [the English] are more polite in eating than the French, devouring less bread, but more meat, which they roast in perfection; they put a great deal of sugar in their drink; their beds are covered with tapestry, even those of farmers; they are often molested with the scurvy, said to have first crept into England with the Norman Conquest . . .

This sugar, though, had dire consequences, Hentzner thought, as he reported on the English sovereign, Elizabeth I:

. . . next came the queen in the sixty-fifth year of her age, as we were told, very majestic; her face oblong, fair, but wrinkled; her eyes small, yet black and pleasant; her nose a little hooked; her lips narrow, and her teeth black; (a defect the English seem subject to, from their too great use of sugar) . . .

A number among the courtiers he met would have been benefiting from the price sugar commanded, for even as its availability increased, so did the hunger for sweet tastes, and the courtiers, as was common, benefited from trade even as they pretended to despise the traders. They sent ships to the Mediterranean to trade in sugar, and to Madeira where they bought sweet wines and sugar, and they also traded in fine sugar from Amsterdam. By the time Shakespeare posed the apparent puzzle of the Clown’s sugar in 1609, everybody knew about sugar, even if they had not actually tasted it. Soon, even that would change.

One curiosity, though: the usual editions of Hentzner’s account of his travels feature a drawing of Queen Elizabeth, the work of one Signor Zuccaro. Given his name, it is hard to avoid mentioning that, sweetly and wisely, Signor Zuccaro did not show the Queen’s teeth.

PIRATES AND TRADERS

Sir John Hawkyns (to use his own spelling) was a Devon man like his kinsman, Francis Drake, and he is often called the first English slave trader. While he did indeed sell a few slaves that he took from Portuguese ships, his justification would have been that he did not trade regularly in slaves, that he did not take slaves, but that he needed slaves to force a trade with the Spaniards. Much of this was true. A more valid (and more honest) justification might have been that if priests and prelates, rulers and great lords could see no harm in taking and trading slaves, why should he object to making a fortune?

Whatever the case, it was the age of the seadog, and there was just one law at sea: if you saw a foreign ship and thought you could capture it, you did—and if you thought it could capture you, you fled. It was a seadog-eat-seadog world—that was something Hawkyns knew well, and so did all the Devon men.

Thomas Wyndham was very much the genuine seadog. He had sailed with Hawkyns’ father and later mounted his own expeditions. In 1552 Wyndham was master of the Lion, when he was forced to land in the Canaries, on a small island between Fuerteventura and Lanzarote, to mend a leak below the waterline. His crew took 70 chests of sugar ashore to lighten the ship, but these chests were seen by islanders who claimed they came from a ship that had just left port, which led to Wyndham being accused of piracy.

The matter was sorted out easily enough when Wyndham’s men captured the governor, a man he described as ‘a very aged gentleman of seventy’; being thus well placed to negotiate, they made good their departure. A year later Wyndham died on the way home after he had sailed to the African coast with another ship, seeking trade in gold and pepper, but he had shown the way to work. You can negotiate with the Dons, said the Devon men, but you need to get them over a barrel first, if you want the best of the bargain. That was the norm for trade in those times, and if Wyndham had in truth taken the chests of sugar, well, that would not have been unusual either.

In 1562 John Hawkyns was 30 years old, and he was ready to go trading. He sailed for Africa, planning to go after things like gold dust and ivory, materials which had a ready home market. He sailed for Africa in three ships, with the financial backing of the treasurer of the navy (it helped some that this official was also his father-in-law), two city magistrates, the Lord Mayor of London, a future Lord Mayor and, most importantly, Queen Elizabeth herself. They captured 300 slaves, mainly by taking them from Portuguese ships headed for the Cape Verde Islands and, having annoyed the Portuguese, set out to tweak a few Spanish beards.

Arriving at Hispaniola, Hawkyns claimed he needed to careen his ships and that he could only pay for this by selling some of the slaves. Then, having opened up the trade to raise careening money, he opened it up a little more and so managed to return to England with a clear profit. That, at least, was the story the two sides told—it is likely that the Spanish colonists, chafing under trading restrictions imposed by the home government, were happy to play along with a neat cover story.

On his third voyage, Hawkyns sailed with six ships, two of them belonging to the Queen herself. At the Spanish colonial port of Rio de la Hacha, the English fleet fired off a few cannon and took the town. Once they were ashore and safely in charge, two slaves, one a mulatto, the other a Negro, revealed where some Spanish treasure was hidden in exchange for help in gaining their freedom.

Hawkyns claimed afterwards that because he was an honest trader he took only 4000 pesos from the treasure for each of the slaves he left in the town, and returned the rest. Then, because the loyalties of race and class counted for more than the loyalties of nationality or religion, he handed over the slaves who had so treacherously revealed where the treasure was hidden. The Spaniards, equally keen to respect this assistance from a gallant and honourable adversary, and sensitive to distinctions of either race or guilt, promptly quartered the Negro, and hanged the mulatto, both for treason.

Once again, the story may be open to some doubt, since the Spaniards claimed the slaves they were forced to buy were old and feeble, sickly and dying. Perhaps the execution of the traitorous slaves was a fiction added to the tale to make it sound better, or perhaps they really were done to death so that the guilty parties would not meet a similar fate.

Hawkyns’ modern English apologists argue that the slaves he sold were used to extort money from the Spanish and to stimulate trading—so he was not so much trading in slaves as using them so that he could trade. The end result, though, was that his third voyage brought the first West Indies sugar into England, and Francis Drake had gained valuable experience in dealing harshly with the Spanish. You needed a fierce resolve, cold steel, iron cannonballs and plenty of lead musketballs to trade on an even footing with the Dons.

Curiously, lead is a recurring theme in the story of sugar. Alexander VI, the Pope who approved the Treaty of Tordesillas, father of Cesar and Lucrezia Borgia (among others), bribed and poisoned his way to the papal throne. He probably died of a fever, though at the time there were plenty willing to believe that he had accidentally drunk poisoned wine set aside for Cardinal Corneto, and so suffered a just fate. That, at least, is the story that Alexandre Dumas told in one of his novels.

The poison the Borgias used was probably lead acetate, a soluble lead salt, known from its sweet taste as ‘sugar of lead’. It is likely that Corneto’s wine, if it was his, was laced with this. But whether or not Pope Alexander VI died in this ironic (leadic?) way, we will probably never know.

There was another link between lead and sugar, apart from the use of lead pipes to carry cane juice from the mill to the boiler-house. Around AD 1000, lead acetate was used in Egypt as a defecant, an agent to clean the heated cane juice, but using lead like this was soon banned. After that time, suspect syrups were exposed near a latrine where the action of hydrogen sulfide coming from the cesspit would produce a tell-tale black precipitate of lead sulfide in the syrup.

In 1847 a British patent proposed the use of lead salts in the preparation of sugar, an idea which alarmed so many people that Earl Grey felt the need to send a circular to all British colonial governors, warning them against allowing it.

THE INDENTURED SERVANTS

Given the piratical habits of all sides, it is hardly surprising that when William and John, the first British ship to reach Barbados, arrived there in 1627, it carried 80 English settlers, and also half a dozen Negroes plundered from a Portuguese vessel ‘met’ on the way. On the return voyage, the crew captured a Portuguese ship with a cargo of sugar. This cargo was sold for £9600, which went to benefit the colonists. While the colony might thus seem to have begun on a combination of black slaves and sugar, it really began with indentured white labour, and with crops other than sugar.

A year after the British had first settled on Barbados, Henry Winthrop reported a mere ‘50 slaves of Indeynes and Blacks’— and that included the blacks collected on the way to the island. Between 1628 and 1803 the island imported 350 000 slaves, of whom 100 000 were women, but when the last of the slaves were freed in 1834 they were just 66 000 in number. Many of those would have been born after imported slaves stopped arriving, for when slaves could no longer be shipped in, breeding was encouraged. For a comparison, in the United States, between 1803 when the importing of slaves was officially banned, and 1865, the slave population increased tenfold due to internal population increase.

The white indentured servants of the seventeenth-century colonies were seen as people excess to the needs of the home nations. As early as 1610, Governor Dale of Virginia pointed out that the Spanish had greatly added to the (white) populations of their American colonies by sending out their poor, their rogues, their vagrants and their convicts. In 1629 Henry Winthrop realised that he needed ‘every yere sume twenty three servants’ to work his tobacco plantation in Barbados. While these were not always available, the English Civil War began to provide shipments of prisoners in 1642. Soon a group of kidnappers known as the Spirits became active, ‘crimping’ or kidnapping people who found themselves carried to Barbados, where the ships’ captains would, in effect, sell them into slavery.

Many of these servants were seen as troublemakers in their new homes. The Scots servants were rated more highly than the English; the Irish servants were rated so poorly that the Barbados Assembly enacted a law in 1644 against any increase in their numbers. Because Barbados had to take what it could get, however, some 20 per cent of servants were still Irish in 1660.

In the meantime, yellow fever had come to the New World with the African slave ships. Spread by the mosquito Aedes aegypti, it had to wait until a fast trip carried a single generation of mosquitoes across the Atlantic from Africa in the open barrels of foul drinking water. Once they reached the islands and South America, the insects dispersed and passed the disease on. To European populations, this tropical disease was a serious threat. Those who survived never got it again, so an immune population of survivors eventually developed, but new arrivals were always at risk.

A yellow fever epidemic on Barbados around 1647 killed an estimated 6000 whites, many of them indentured servants. This increased the demand for black slaves in the 1650s, but for the moment the wars in Britain kept up the supply of indentured servants. As the number of black slaves increased, cheap white labour was needed to keep control. An Act of 1652 provided a solution, allowing two justices of the peace to

. . . from tyme to tyme by warrant . . . cause to be apprehended, seized on and detained all and every person or persons that shall be found begging and vagrant . . . to be conveyed into the port of London, or unto any other port . . . from which such person or persons may be shipped . . . into any forraign collonie or plantation . . .

In other words, the magistrates, who represented the wealthy of a borough or parish, could ensure that the poor, who otherwise would be a cost to the parish, were rapidly and permanently removed. Note the use here of ‘plantation’ as a synonym for ‘colony’. Up until about 1650 it was people who were thought of as planted, and settlements of English families in Wales or Scotland were also ‘plantations’. It was only later that plantation came to mean a single (generally monocultural) farm. When first settled, Barbados was a plantation of people; it became a sugar plantation when sugar cane was introduced, and then a sugar colony filled with sugar plantations.

THE WHITE SLAVES

The indentured servants who survived the yellow fever probably saw themselves as fortunate, especially those who had gone to the

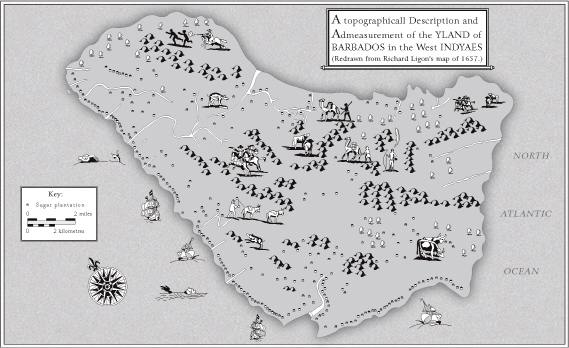

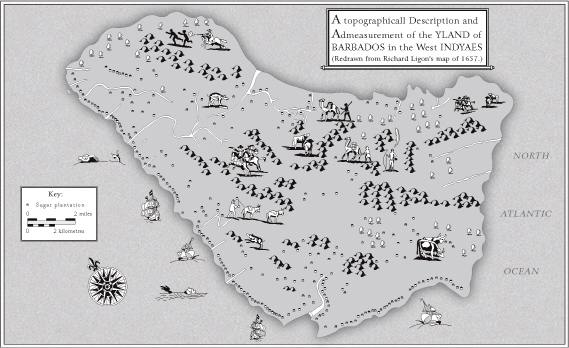

For the most part, the plantations of Barbados were clustered near the coast.

islands of their own accord and were able to hire themselves out. The servants who had been ‘Barbadoed’ by a court on a trumped-up charge, or stolen away from their families by the Spirits and sold into virtual slavery in the islands, might have accounted themselves fortunate to get out of plague-ridden London, but many died of island diseases instead. For some this would have been a happy release. It was the island diseases that kept servants in short supply, so that judges in England and Ireland would happily find prisoners guilty and send them to the West Indies, or ‘Barbadoe’ them, as the saying went. It was why the Spirits were able to operate in the various ports; because there was such a shortage of servants they could pay well for people to turn a blind eye, knowing they would be well paid for all they captured.

The Spirits got up to all sorts of tricks, the same ones the crimps of that time played on sailors, using knock-out potions or getting people drunk, and sending the victims to sea with forged papers showing they were indentured. This meant the victim would spend seven years working for a master who generally cared little for the welfare of a servant who would be lost to him at the end of that time.

Of course, not all the servants could get away from their indentures. Under a code passed in 1661, setting out the rights of master and servant, the servants, just like slaves, were forbidden to engage in commerce, and any of a large number of petty offences could lead to a year being added to the period of servitude. Passes were required for servants to be off their master’s property, and the dishonest master had plenty of opportunities to goad servants into punishable actions so their periods of servitude could be extended.

Being indentured was so bad that when Generals Penn and Venables were in Barbados in 1654 to outfit for their attack on Hispaniola and Jamaica, many servants ran away to the ships— while those on the ships, knowing what life at sea was like, fled ashore. In the end, Cromwell’s great Western Design to undo Catholic Spain meant 2000 servants from Barbados perished on Jamaica, so in February 1656 Cromwell sent troops into London to find 1200 women of ‘loose life’ and send them to Barbados. Within days another 400 were sent off.

The planters always complained about the servants. Even though Scotland was under the same king, it was still a different country, and the planters asked in 1667 to be allowed free trade in servants with Scotland, and to transport 1000 to 2000 English servants to the colony. Still nobody wanted the Irish, because it was believed that, being Roman Catholic, they were likely to help the French or the Spanish if they could. The proportion of servants to slaves was a bigger worry, however, so the planters still took what servants they could get.

By 1680 there were only 3000 indentured servants on Barbados, down from 13 000 in the 1650s. By that time there were so many slaves that the masters used all sorts of legal tricks to hold their indentured servants, but those who were out of indenture could pick and choose where and how they worked.

When the Monmouth rebellion broke out in 1685, the planters got a break. The bastard Duke of Monmouth tried to seize the British throne but failed, and his followers were either put to death or, more often, Barbadoed. The Spirits had a fine old time, snatching extra bodies and sending them off with papers showing their victims as convicted rebels.

Most of the former servants had skills that were badly needed, and they could set their own price. Many of the advances in sugar preparation (like the Jamaica Train discussed in Chapter 6) must have come from servants who had reached sugar master status. They had got their training thanks to the Spanish Inquisition and the way the inquisitors had treated the Portuguese Jews, who had been happy and safe in Portugal until a few years before the Great Armada, when Spain took over Portugal and the Inquisition moved in on the Jews.

Most of the Jews in Portugal had fled Spain and its Inquisition a generation or two earlier, and now they shifted again, to Holland, where they were welcomed for their skills. Some of them moved to South America when the Dutch took over Per-nambuco in the north of Brazil. The Jews, seen as an under-class, managed the daily operations of the plantations, and more importantly, the mills. When the Dutch were forced out of Pernambuco, many of the Jews went with them to Amsterdam, but others went to Barbados, where they provided the skills base that the English sugar planters desperately needed.

THE ROYALIST REFUGEE

During the turmoil of the English Civil War of the 1640s, the royalist Richard Ligon felt it would be safer to be out of England than to stay there. So he took himself off to the peace and calm of the plantation of Barbados in 1647, not returning home until 1650, by which time life in England was a little more stable.

He spent a pleasant enough three years, learning the art of sugar making among other things, and set down what he saw in A True & Exact History of the Island of Barbados. Because he was there long enough to observe closely, but not long enough to become part of the community, Ligon’s account gives us the truth, hopefully unvarnished by any desire to censor the facts. For example, he explains that:

The slaves and their posterity, being subject to their Masters for ever, are preserv’d and kept with greater care than the servants, who are theirs but for five years, according to the law of the island. So that for the time, the servants have the worser lives, for they are put to very hard labour, ill lodging, and their dyet very slight. Most of them are Irish and a sullen bunch, but that may be on account of the treatment meted out to them, I know not. The usage of the Servants, is much as the Master is, merciful or cruel. Those that are merciful, treat their Servants well, but if the Masters be cruel, the Servants have very wearisome lives.

Before his time in the island, he tells us,

. . . the first people in Barbados, made tryal first of tobacco, cotton, indigo, and only then turned to sugar canes. The planters made tryal of them and finding them to grow, they planted more and more, as they grew and multiplyed on the place, till they had such a considerable number, as they were worth the while to set up a very small Ingenio, as we call the place where crushing and boiling down to make the sugar takes place.

At the Ingenio, he reports, the cut cane is placed on a platform called a Barbycu, a raised stand with a double rail to stop the cane falling out, about 9 metres long and 3 metres wide (in spite of the size, this was a close relation to our modern barbecue).

Then there is a set of three rollers, with perhaps five horses or oxen driving the middle roller, ‘which is cog’d to the other two, at both ends’:

A Negre puts in the canes of one side, and the rollers draw them through to the other side, where another Negre stands and receives them and returns them back on the other side of the middle roller which draws the other way. So that having past twice through, that is forth and back, it is conceived that all the juice is prest out; yet the Spaniards have a press, after both the former grindings, to press out the remainder of the liquor . . .

But that, he explains in a bluff patriotic manner, is because the Spaniards’ cane is poorer. The crushed cane is set aside, some six-score paces away, and the juice:

. . . runs under ground in a Pipe or gutter of lead, cover’d over close, which pipe or gutter, carries it into the Cistern, which is fixt neer the staires, as you go down from the Mill-house to the boyling house. But it must not remain in the Cisterne above one day, lest it grow sowr; from thence it is to passe through a gutter, (fixt to the wall) to the Clarifying Copper . . . As the skumme rises, it is conveyed away, as also the skumme from the second Copper, both which skimmings, are not esteem’d worth the labour of stilling; because the skum is dirtie and gross: But the skimmings of the other three Coppers, are conveyed down to the Still-house, there to remain in the Cisterns, till it be a little sowr, for till then it will not come over the helme and make good rum.

. . . there is thrown into the four last Coppers, a liquor made of water and ashes which they call Temper, without which, the Sugar would continue a clammy substance and never kerne. Once the sugar master has determined that the sugar in the last copper is ready, two teaspoonfuls of Sallet Oyle [salad oil], such as we put on raw vegetables to make a sallet, are added and then the syrup is ladled out. Above all, it is important to throw in some cold water, in order that the last of the syrup should not burn, for the copper is fixed in place over an open fire, and as soon as the copper is empty, syrup from the penultimate copper must be added.

. . . And so the work goes on, from Munday morning at one a clock, till Saturday night, (at which time the fires in the Furnaces are put out) all houres of the day and night, with fresh supplies of men, Horses and Cattle. The liquor being come to such a coolness, as it is fit to be put in the Pots, they bring them neer the Cooler, and stopping first the sharp end of the Pot (which is the bottom) with Plantine leaves, (and the passage there no bigger than a man’s finger will go in at) they fill the Pot and set it between the stantions in the filling room, where it staies till it be thorough cold, which will be in two days and two nights; and then if the Sugar be good, to be removed into the Cureing house, but first the stopples are to be pulled out of the bottom of the pots, that the Molosses may vent itself at that hole.

. . . The Molosses, in a well-run Ingenio, is converted into Peneles, a kind of Sugar somewhat inferiour to the Muscovado. . . . And this is the whole process of making the Muscovado Sugar, whereof some is better, and some worse, as the Canes are; for, ill Canes can never make good Sugar.

I call those ill, that are gathered either before or after the time of such ripeness, or are eaten by Rats and so consequently rotten, or pulled down by the vines men call Withes, or lodged by foule weather and ill winds, either or which, will serve to spoil such Sugar as is made of them.

A major improvement in the lot of the planters came when rum became part of the sugar industry. It made marginal operations profitable, loss-making plantations became profitable, and planters still losing money found a new comfort. Almost nothing was too poor to go into the fermentation vats, other than the first couple of skimmings from the coppers. Richard Ligon is once again one of our best witnesses:

After it has remained in the Cisterns . . . till it be a little soure, (for till then, the Spirits will not rise in the Still) the first Spirit that comes off, is a small Liquor, which we call low-wines, which Liquor we put into the Still, and draw it off again; and of that comes so strong a Spirit, as a candle being brought to a near distance, to the bung of a Hogshead or But, where it is kept, the Spirits will flie to it, and . . . set all afire.

This volatility of the rum made it quite risky, and Ligon describes how they ‘lost an excellent Negro’ to a rum explosion when a candle was used for illumination while a jar of spirit was being added to a butt of rum:

. . . the Spirit being stirr’d by that motion, flew out, and got hold of the flame of the Candle, and so set all on fire and burnt the poor Negro to death, who was an excellent servant. And if he had in the instant of firing, clapt his hand on the bung, all had been saved; but he that knew not that cure, lost the whole vessel of Spirits, and his life to boot . . .

This drink, though it had the ill hap to kill one Negro, yet it has had the vertue to cure many; for when they are ill, with taking cold, (which they often are) . . . they complain to the Apothecary of the Plantation, which we call the Doctor, and he gives to every one a dram cup of this Spirit, and that is a present cure. And as this drink is of great use, to cure and refresh the poor Negroes, whom we ought to have a special care of, by the labour of whose hands, our profit is brought in; so it is helpful to our Christian servants too . . .

The distinction they made between their servants may seem an odd one, but Ligon explains even this:

Once I encountered a slave who wished to be a Christian, but on interceding with the slave’s master, I was told that the people of the Island were governed by the Lawes of England, and by those Lawes, we could not make a Christian a Slave. I told him, my request was far different from that, for I desired him to make a Slave a Christian. His answer was, That it was true, there was a great difference in that: But, being once a Christian, he could no more account him a Slave, and so lose the hold they had of them as Slaves, by making them Christians; and by that means should open such a gap, as all the Planters in the Island would curse him.

To read the testimony of the planters, nothing was ever easy for them. That is one point at which Ligon was in complete agreement with later writers with the mindset of the plantation owner.

DERBY’S DOSE

The planter could make a good profit, but there was always the risk of bad weather, insurrection or war, not to mention death from disease (or taxes from a home government). The planter had to buy, clear and plant the land, buy Guinea grass for the animals, set up gardens for the slaves, and general working and living space. Purchases included tools, nails, hoops and staves for barrels, lime, cooking pots, building material, food for the slaves, equipment for the mill and boiling house, and then there were the skilled staff: even if these were slaves, they could still command extra allowances—and many of them were free men, former indentured servants now out of their indentures.

The overseer, distiller, carpenter, drivers and wainmen, cooper, foreman sawyer, fireman, watchman, field-children’s nurse, potter and ‘black doctor’ had all to be paid, as well as domestic servants. But above all, the slaves had to be fed, and while bought food was expensive, the food crops perversely needed the most cultivation just when the sugar needed harvesting!

The slaves were fed well enough at times, though for the most part planters tried to keep costs down by using local resources. The areas between cane plots could be planted with food crops, including such crops as yams, eddoes and bananas, brought from Africa by the slave ships. William Bligh’s ill-fated breadfruit was one of the few failures; the slaves did not like the taste, and it was only well into the nineteenth century that people in the Caribbean began to eat it.

Hard physical labour requires protein, and sweaty work requires salt. It did not take long for the canny cod fishermen of New England to identify a new and not particularly fussy market. Their rejects, the badly split fish and fish with too much salt or not enough, could all be disposed of as ‘West India cure’, destined to feed the slaves. During the eighteenth century, in times of unrestricted trade, on average a ship would leave Boston every day for the West Indies, laden with reject fish. Around 1650, Richard Ligon saw that fish could be found closer to home, and he wrote in his Exact History:

As for the Indians, we have but few, and those fetcht from other Countries; some from the neighbouring Islands, some from the Main, which we make slaves: the women who are better vers’d in ordering the Cassavie and making bread, than the Negroes, we imploy for that purpose and also for making Mobbie; the men we use for footmen and killing of fish, which they are good at; with their own bowes and arrows they will go out; and in a dayes time, kill as much fish as will serve a family of a dozen persons, two or three dayes if you can keep the fish so long.

Other foods for the slaves varied from island to island. Jamaica had more free land than Barbados, enabling the slaves there to tend gardens where they grew food. Barbados was necessarily more dependent on outside sources, importing maize and rice from America and horse beans from Britain. Reliable figures are hard to come by, but one record exists of newly purchased slaves with no planted ground getting one fish and either nine plantains, two pints of rice or three pints of maize, each day. The food rations, it would seem, were minimal and monotonous, and might have accounted for the short working lives of most slaves.

During the sugar harvest there was cane to chew and syrup to drink, but by the end of the harvest the provision grounds were least productive. Thomas Thistlewood, an overseer in Jamaica in the middle of the eighteenth century, recorded signs of poor nutrition among the slaves in August and September, over a number of years. His diary for 25 May 1756, as quoted by Ward, reveals that a slave called Derby was caught eating the young canes—a definite offence, since it meant a reduced crop later on: ‘Derby catched by Port Royal eating canes. Had him well flogged and pickled, then made Hector shit in his mouth.’ This treatment, referred to thereafter as ‘Derby’s Dose’, did not seem to deter the offender, who appears in Thistlewood’s diary again in August:

Last night Derby attempting to steal corn out of Long Pond corn pieces, was catched by the watchman, and resisting, received many great wounds with a mascheat [machete], in the head etc. Particularly his right ear, cheek and jaw, almost cut off.

There is no record of what happened to Derby after that. It seems unlikely he survived, though. The excerpts from Thistlewood’s journal quoted by Ward clearly reveal his care and consideration for those under his charge— when they weren’t stealing food, that is. All sorts of odd punishments, including lockable masks of tinplate, were used to stop slaves eating the young cane. Wearing the mask was probably preferable to what happened to Derby. In some areas, the masks were also worn by kitchen slaves to stop them tasting the food they were preparing.

Forced to labour in the sugar mills from sunrise to late at night, it was inevitable that weary slaves would lose concentration and risk injury. The greatest danger came at the height of the season, when they were toiling away close to huge pans of sticky, scalding sugar juice, working for up to eighteen hours a day in fierce heat in the rush to deal with the huge masses of ripe cane that came in. Outside, the slaves who fed the cane into the rollers worked in cooler conditions, but they were just as much at risk of injury through being trapped by the rollers.

The three-roller mill was standard, and while some early ones were powered by humans, most were under animal, wind, water or steam power and slower to react to a human scream. A hatchet or cutlass was kept in a convenient place, ready to chop off the arm of any slave who was trapped—in order to save the slave’s life. It made better economic sense to keep alive a slave with one arm, because that slave could still act as a watchman, clear blocked drains or guide the animals that did the heavy haulage.

While there is probably a degree of exaggeration in the tales the emancipists told later of slavery, it would be unwise to assume that the life of a slave was a pleasant one. The way slaves took advantage of unrest made this very clear—in fact, slaves were one reason not to fight wars in the Caribbean.

The territorial claims made by Spain and Portugal under the Treaty of Tordesillas could not be defended against the combined forces of the English, Dutch and French, and in the end Spain was forced during the seventeenth century to accept the presence of other powers in the Caribbean islands, just as Portugal had to accept the British and French in India and Africa, and the Dutch in the East Indies. In one case, the Spaniards shared the island of Hispaniola with the French.

Aside from anything else, whatever armed forces the Europeans had in the West Indies were needed there to maintain order in their own colonies. When the home nations went to war, extra forces would be sent in to attack and pillage the colonies and the shipping of the enemy, even though this caused unrest among the slaves.

TO DRIE APRICOCKS, PEACHES, PIPPINS OR PEARPLUMS

Take your apricocks or pearplums, & let them boile one walme in as much clarified sugar as will cover them, so let them lie infused in an earthen pan three days, then take out your fruits, & boile your syrupe againe, when you have thus used them three times then put half a pound of drie sugar into your syrupe, & so let it boile till it comes to a very thick syrup, wherein let your fruits boile leysurelie 3 or 4 walmes, then take them foorth of the syrup, then plant them on a lettice of rods or wyer, & so put them into yor stewe, & every second day turne them & when they be through dry you may box them & keep them all the year; before you set them to drying you must wash them in a little warme water, when they are half drie you must dust a little sugar upon them throw a fine Lawne.

Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book, 1604