Bryan Edwards, a planter and early historian of the West Indies, explained war in his neighbourhood like this:

Whenever the nations of Europe are engaged, from whatever cause, in war with each other, these unhappy countries are constantly made the theatre of its operations. Thither the combatants repair, as to the arena, to decide their differences.

According to Edwards, this was because the combatants who survived could make themselves rich. In the late eighteenth century, foreign navies plundered British merchant ships and kept the profits while Britain’s navy made a treasure trove of the foreign trading vessels. But did the navies compensate the planters for their losses? Indeed they did not, the planters complained. The arena for their grudge matches was inevitably the lucrative Caribbean, but paying compensation to the planters would have eaten into their profits.

The warring navies chose the Caribbean, far from their home waters, for the rich cargoes carried in the area, and because of the way that prize money works in times of war, especially

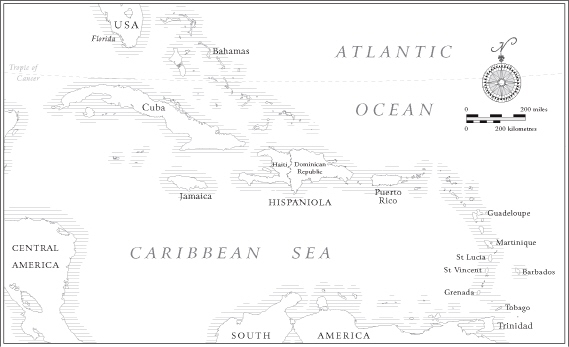

The West Indies.

benefiting frigate captains whose ships were large enough to sail independently, and fast enough to run down almost any ship on the ocean. Edwards conceded that sometimes the British planters would gain, since Britain usually held the upper hand in privateering and blockading. This meant the French sugar trade was often badly affected, allowing English sugar interests a greater slice of the European market. At the same time, Royal Navy ships provided a ready market for rum, but the planters were not happy—it was not in their nature to be happy.

Prize money was paid for all ships and cargoes captured. It was divided in a complex manner, with larger sums going to the more senior officers, and many captains—if they survived long enough—became landed gentry in their later years. Frigates did best of all, because if a capture was out of the sight of the commanding admiral, the admiral’s portion was also divided among the officers and crew.

Sometimes the naval officers were a bit greedy. Tradition has it that Josias Rogers, captain of the Quebec, was so impressed by the sight of a bullion-laden Spanish treasure ship, brought into Portsmouth during the Seven Years’ War, that he determined to enter the navy and have a share in such riches. He did quite well from the War of American Independence, and settled on an estate in Hampshire, but when his banker failed and he lost half his fortune, Rogers just went back to sea to get some more. In the first five weeks of 1794 he took nine prizes, and estimated that his share of the proceeds would be £10 000.

The Royal Navy had taken more than 300 merchant ships in 1794, mainly American neutrals, in this legalised form of plunder. The prize courts later rejected half the claims on the ground that these neutral ships were sailing between neutral ports and not subject to seizure, but Captain Rogers and his crew still gained from three of their nine prizes. He later spent £3000 in contesting the lost cases, but Rogers did not enjoy his restored wealth for long, however—he saw both his younger brother and nephew die of yellow fever before he succumbed to the same disease in 1795. There were rich pickings for those who survived, but many more lost their lives to disease.

The naval physician, Sir Gilbert Blane, found that in one year alone, 1779, England’s West Indies fleet lost an eighth of its 12 019 seamen to disease—a total of 1518 dead, with another 350 ‘rendered unserviceable’. In 1794, the then Vice-Admiral Jervis’ West Indies squadron lost about a fifth of its men to disease in just six months. The 89 000 soldiers of all ranks serving in the West Indies between 1793 and 1801 suffered 45 000 deaths, 14 000 discharged and 3000 desertions. Small wonder that British troops being sent to the West Indies were usually sent first to the Isle of Wight or Spike Island in the Cove of Cork, to prevent them deserting en masse. German and French mercenary units particularly objected to being sent to what they saw as certain death, and either deserted or mutinied at the prospect. While soldiers could also earn prize money, there was generally less to be had on land than on sea, and a much better chance of falling to disease.

This was why the army and the navy had different views of war in the islands. On land, yellow fever was almost a certainty, and too many of the soldiers died of disease, trying to win from France sugar islands Britain did not need. Henry Addington, arguably Britain’s worst Prime Minister, was not exaggerating when he later told the House of Commons that the West Indies had destroyed the British army. Still, the navy was happy, because of the rich pickings, while the government could only see the French losing sugar and sugar income.

The rich pickings included vast quantities of molasses, rum and raw sugar. But while sugar was undoubtedly the most valuable booty, there were other riches to be had from the Caribbean—coffee, cocoa, cotton, indigo and ginger. While most of these products came also from other places, and Britain was never much of a market for coffee (because the East India Company’s tea was more popular), these cargoes were all of value in the European markets. That raises a question: why did people grow so many of these things in one place, concentrating the riches and increasing the risks?

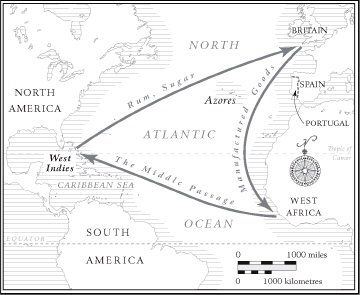

Part of the answer lies in the wind patterns of the Atlantic, because all the produce had to be carried to distant markets in sailing ships. Part lies in the climate of the islands, and part lies in the fact that the plantations were close to the sea, allowing ready transport to the ocean-going ships that carried the cargo away. Wind patterns established the two main triangular trades: dried cod from North America to Africa, slaves from Africa to

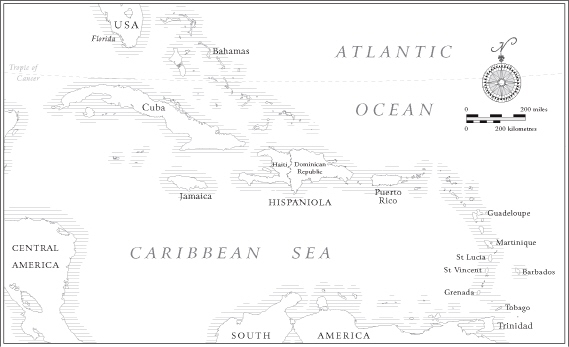

The triangular trade.

the Caribbean and molasses or rum from the Caribbean to New England; and cheap manufactured goods from England, mainly textiles from Lancashire and hardware and toys from Birmingham, to Africa, where these were converted into gold dust, ivory and pepper, and slaves for the Caribbean leg, where the proceeds were used to buy sugar, molasses and rum for the homeward journey.

New England ships sometimes sailed an even tighter loop, taking rum to Africa, slaves to the West Indies, and then molasses back to New England to repeat the cycle when the molasses was turned into rum. French, Dutch, Danish and Portuguese ships did similar circuits, with variations—for example, cod to the Canary Islands, and wine from the Canaries to Africa, where it was exchanged for slaves. All of these trades depended on the fact that the quickest way north from Africa involved travelling to the Caribbean first, whether the voyage was to England or New England. Yet through all of this, with so many people benefiting from the trade, the planters were the only ones blamed for all the evil people said was being done.

The planters survived the wars—unlike the soldiers. Well, some of the planters did—some of them fell victim to their own slaves.

FREEDOM FIGHTERS

The white people on the islands believed that coloured nurses could kill young children without trace by using a scarf pin pushed into the head, and whether this was true or not, it was enough to feed the fear. Macandal was a slave who probably lost his arm in a roller accident, but rather than work at clearing drains he ran away into the hills of Saint Domingue. The one-armed runaway started a campaign of poisoning in 1750, slipping quietly into plantations and providing poison to unsuspected accomplices, until he was apprehended and burned alive in 1758.

There were others, less well known but equally effective, because the planters used slaves in their houses as servants, as cooks, as minders of their children, and as mistresses. In a time when the whites showed no mercy to the slaves, the slaves showed no mercy in return.

The planters were right to fear their slaves. The first slave revolt occurred on São Tomé in 1517, and others over the next hundred years caused much damage to that island’s economy. In 1522, black slaves on Hispaniola rose up in the first revolt in the New World, but the first sugar-colony black revolt did not take place until 1656, when two slaves from Angola, Jean and Pedro Leblanc, led a revolt on the French island of Guadeloupe.

There might have been a successful uprising in the British colony of Antigua in 1736 but that one conspirator was arrested for a minor offence. Thinking that he was under arrest for helping plan the coming revolt, he told all. In the end, five slaves were broken on the wheel, five were gibbeted, and another 77 burnt alive. While the loss of human life was no great matter in those days, the loss of property was, and the waste of so many workers shows the fear the white planters were in. And they knew there were always others to try once more.

The Bastille was stormed in Paris in July 1789, but there was no Liberty, Fraternity and Equality for the slaves in the French colonies. On 20 March 1790 the National Assembly stated that the declaration of the rights of man was not to apply to the colonies. Saint Domingue at that time had three classes of citizens: 30 000 white planters and officials, 24 000 sangs mêlés (people of colour) and half a million slaves, along with a few freed blacks. Until 1777, the sangs mêlés had been allowed to go to France for their education and, unlike the slaves, they were well off, with hopes and aspirations.

The French Revolution had divided the colony’s white population, with its leaders remaining royalist while the masses took up the revolutionary cause. It was against this background that the slaves sought their freedom. The three Ogé brothers, Jacques, Victor and Vincent, together with a sang mêlé called Chavane, failed in an insurrection. Jacques and Chavane were broken on the wheel and Vincent was hanged. Victor escaped and was never seen again.

Back in France, a nervous National Assembly passed a decree allowing people of colour the right to sit in parochial and colonial assemblies. When the planters in Saint Domingue ignored this, their slaves rose up in some areas. The sangs mêlés rebelled in the south, but with no support from the slaves there they reached a peace a short time later, which included an amnesty and acceptance of the decree giving them equal rights. Soon, though, the decree was repealed.

Three commissioners arrived from France to take control in January 1792. They brought 6000 troops with them, but the commissioners were advanced revolutionaries. Finding themselves opposed by the planters, who were largely royalists and supporters of the ancien régime, the commissioners called on the slaves for support. This was just the opportunity the slaves needed, and those whites who did not escape to the ships in the harbour were killed. When war broke out between France and Britain in August 1793, the British invaded Saint Domingue, but in the end the slaves won—with the help of disease. Disease won most of the wars when people came to fight in the West Indies, and there were many wars fought over the sugar islands.

As we have seen, one sugar island was shared. The French founded their colony of Saint Domingue on the western side of Hispaniola in 1697, while the Spanish claimed the eastern side of the island as San Domingo. By the end of the eighteenth century, the French colony was the most profitable sugar producer in the New World, and it was sacrificed by mismanagement and misunderstanding. The freedom the revolutionary Jacobins gave themselves in France was not extended to the slaves of Saint Domingue, and the planters found themselves facing a revolution led by a very clever general.

Toussaint L’Ouverture was the son of an African chieftain, which gave him authority amongst his fellow slaves, and he had been given some education. More importantly, he was a leader, and in 1793 he put his leadership to the test, calling on his fellow slaves to join with him in bringing liberty and equality to Saint Domingue. He formed an alliance with the Spaniards on San Domingo until 1794, when the French ratified an act which set the slaves free. He then turned upon his Spanish allies and expelled them. As the whole island was now effectively French, the English decided to attack and make it English, and the freed slaves looked like becoming unfree once more.

The English got a toehold in the south, but an outbreak of yellow fever defeated them. They withdrew in 1798 when Tous-saint promised that all remaining colonists would be spared, and that he would not invade Jamaica. By now the people of Saint Domingue were calling themselves the people of Haiti, and looking to free other slaves.

This would have been disastrous for the English, who had quite recently made Jamaica more secure by transporting the majority of the maroons, the escaped slaves of Jamaica, first to Nova Scotia and then to Sierra Leone. The English were terrified that the Haitians might inspire the Jamaican slaves to revolt. After all, they knew Toussaint to be a dangerous man, from a letter he wrote to the Directory, France’s ruling body before Napoleon seized power, seen here in James’ translation:

We know that they seek to impose some of them on you by illusory and specious promises, in order to see renewed in this colony its former scenes of horror. Already perfidious emissaries have stepped in among us to ferment the destructive leaven prepared by the hands of liberti-cides. But they will not succeed. I swear it by all that liberty holds most sacred. My attachment to France, my knowledge of the blacks, make it my duty not to leave you ignorant either of the crimes which they meditate or the oath that we renew, to bury ourselves under the ruins of a country revived by liberty rather than suffer the return of slavery. . . . But if, to re-establish slavery in San Domingo [the Decree of 16 Pluviôse were revoked], then I declare to you it would be to attempt the impossible: we have known how to face dangers to obtain our liberty, we shall know how to brave death to maintain it.

Toussaint took much of the credit for the withdrawal of the English, and the French made him a general, with the titles of Lieutenant-Governor and Commander-in-Chief of the Haitian forces. The standard wisdom, though, is that Toussaint did not make the revolution, it was the revolution that made Toussaint.

Toussaint declared himself in 1801 to be Governor-General for life, showing little respect for Haiti’s official owner, Napoleon Bonaparte. French honour had to be satisfied—and French sugar and sugar incomes had to be restored. The French attacked, led by Napoleon’s brother-in-law Leclerc. The military response to the heat of the tropics was to confine the soldiers to their barracks during the hottest hours of the day—where the mosquito lurked, ready to spread yellow fever, and where troops all too easily succumbed to the temptation offered by cheap rum. If that was not bad enough, in an act of absolute stupidity the French reinstated slavery, which united all of Haiti against them.

In spite of the skyrocketing death rate from disease, the French managed to capture Toussaint by treachery after an armistice, and he was hauled to a prison high in the French Alps where he died soon after. His unhappy end was reflected in a sonnet by Wordsworth:

To Toussaint L’ouverture

Toussaint, the most unhappy man of men!

Whether the whistling Rustic tend his plough

Within thy hearing, or thy head be now

Pillowed in some deep dungeon’s earless den;

O miserable Chieftain! where and when

Wilt thou find patience? Yet die not; do thou

Wear rather in thy bonds a cheerful brow:

Though fallen thyself, never to rise again,

Live, and take comfort. Thou hast left behind

Powers that will work for thee; air, earth, and skies;

There’s not a breathing of the common wind

That will forget thee; thou hast great allies;

Thy friends are exultations, agonies,

And love, and man’s unconquerable mind.

The French might have taken Toussaint, but they had lost 50 000 men, and in the end they lost their most important sugar colony for good. Leclerc died of yellow fever in October 1802, and his replacement, General Rochambeau, was equally unable to overcome the destruction of his army by disease, and he capitulated in November 1803.

Napoleon decided to sell his American colonies to the United States for $15 million. The grand plan he had conceived—to not only retain the sugar wealth of Saint Domingue, but to build a huge French empire in the Mississippi Valley to make up for the loss of Canada during the Seven Years’ War—had come to naught.

With the gain of this new territory—the Louisiana Purchase—the United States was able send the explorers Lewis and Clark to reach the west coast. It would take most of the nineteenth century for the West to be won, but the foundations of modern North America were laid in the mismanaged French sugar colonies of the Caribbean, and in the French willingness to pass up on Liberty, Equality and Fraternity, when those ideals stood between them and making sugar profits.

All the same, the French did not lose out entirely. In November 1814 the island of Guadeloupe, which Napoleon’s France had also lost to England, was returned to newly royalist France. On duty there, Edward Codrington (later Admiral Sir Edward Codrington) noted sardonically in his Memoir that:

The people of this island will, I suspect, have cause to regret the change in their government, for there are already sixty clerks come to do what eleven have done under us . . . and the whole of these . . . are to be paid by the islanders who will be taxed enormously, and be unable to profit by the permission to purchase negroes.

Some of the people of the island had even more immediate regrets, for unlike the people of Haiti, those on Guadeloupe who had been slaves were to become slaves again, as Codrington noted in another letter:

. . . the spot was pointed out to me as the last retreat of those who were struggling for liberty. A considerable number of people of colour who saw no hope left but a return to slavery, by joint consent blew themselves up together rather than ask life upon such degrading terms.

In the peace after Waterloo, the British sugar growers on Jamaica and the smaller islands found themselves faced with plummetting sugar prices. They also knew the slaves had a role model to look to on Haiti, a promise of freedom that might one day be seized, for even if the hated slave trade had been stopped, slavers were still sailing the oceans under the flags of other nations, and the slaves were still slaves. England needed the profits, and everybody needed their sugar, just as Ralph Clark did.

SUGAR, COFFY AND RALPH CLARK

Ralph Clark comes into our view first as a marine who sailed for Sydney on the convict transport Friendship when Arthur Phillip’s First Fleet set out to create a settlement at Botany Bay. He, and the rest of the fleet, faced uncertain prospects on the other side of the world from ‘home’, and he quickly realised that some things would have to change. He wrote in his journal, in his idiosyncratic spelling:

. . . to day for the first time in my life drinked my tea without Sugar which I intend to doe all the Voyage as my Sugar begins to grou Short therfor will only drink tea and Sugar now and after we get on Shore on certaind days . . .

Clearly, the fleet carried some sugar, but this seemed to be mainly as a form of medicine, because it is mainly the surgeons who seem to have mentioned it in surviving records. Surgeon John White complained that his first hospital in Sydney had no sugar, sago, barley, rice or oatmeal, all essential hospital supplies, but Arthur Bowes Smyth, surgeon on the Lady Penrhyn, records how, on the journey out, he gave ‘a quantity of Sagoe & soft sugar to every Birth [berth] of the Women as an indulgence, as I had plenty of both by me’. In fact, it was not until Lady Penrhyn was almost to China, on the journey back to Europe, that he recorded running out of sugar, just days before dropping anchor at Macao, where he was able to replenish his stocks.

Clark, though, was less fortunate. The commander of the First Fleet, and Governor, Arthur Phillip, had collected some sugar cane at the Cape of Good Hope, and while some seems to have been tried unsuccessfully in Sydney, most of it was sent on to Norfolk Island, to the north-east of Sydney. Supposedly, the sugar cane did well, or so Lieutenant King said. In a surviving letter, Clark notes darkly that Lieutenant King had written to Sir Joseph Banks about how he had made both sugar and rum, but the marines saw none of it, and Mr King, said Clark, ‘would not make his dispatches Public, because he knew they did not agree with the Private Accounts’.

There is a whiff of scandal here, but there was to be no whiff of sugar, molasses or rum for the poor marine lieutenant. In early 1791, Clark wrote in his journal that he yearned for tea and sugar, adding that he had not had tea or wine for six months. There was no coffee, either:

. . . our Breakfast is dry bread and Coffy made from burnt wheat and we are glad even to be able to get that—God help use I hope we will Soon See better days Soon for the[y] cannot well be Worse.

A week later, with hope that a ship was about to arrive, he repeated his hope for tea and sugar, but it seems he had to wait until May for any sugar. As early as 1788, Clark had written to a brother officer at Plymouth, asking for

Viz: 6 or 8 lb of Tea, about 40 or 50 lb of Sugar, 6 lb of Pepper, 2 pices of printed Cotton at about 3 or 4 dollars a pice for window Curtains and a dozen the Same Kind of plates as You gave me and let me know what the cost and I will Send you ane order for the Same—be So good as to make my best and tendrest wishes to Mrs. Clark and inform her I have wrote her by this opportunity . . .

While Clark was roughing it in the sugar-free wilds of Australia and Norfolk Island, where he had a daughter by a convict girl named Mary Branham, his wife Betsy was at home in England, caring for his young son, also called Ralph.

Clark returned to England in 1792, and left a pregnant Betsy in England when he sailed off to fight in Haiti in May 1793, taking young Ralph with him to the sugar islands of the Caribbean. There, Clark senior died in a naval action against the French, while his son died, apparently on the same day as his father, of yellow fever; a little earlier, Betsy had died after giving birth to a stillborn child.

Perhaps he died happy though, because in June 1794 he wrote a letter describing how they had taken ‘45 Ships, 36 of them are large Ships, deeply loaded with Sugar, Coffy, Cotten and Indigo’. We can only hope that he got his fill of the captured Coffy and Sugar before he was cut down, leaving behind his incomplete papers, his name on a small island in Sydney Harbour where he once had a garden, and possibly his daughter by Mary Branham, of whom we know nothing more.

SUGAR BECOMES A COMMONPLACE

By the time Ralph Clark died, most Europeans knew and hungered after sugar. The percolation of sugar down the social scale had been slow but steady. In 1513 the King of Portugal sent sugar effigies of the Pope and twelve cardinals to Rome as a mark of his esteem, and in 1515 sugar was taken to King Ferdinand on his deathbed. In 1539 Platine recorded the French proverb: Jamais sucre ne gâta viande (‘adding sugar never hurt any food’)— which only referred to the food of the rich, but that was changing fast. At the end of the sixteenth century, Queen Elizabeth and her courtiers may have rotted their teeth, but sugar had already extended beyond the Court circle. In England in the mid-1800s, when Dickens was writing his novels, sugar in one’s tea was a commonplace throughout British society.

The price of sugar probably tells the story of its filtering down through the classes better than anything else. In modern terms, a kilogram of sugar cost about US$24 in 1350–1400, $16 in 1400–50, $12 in 1450–1500, and $6 in 1500–50, when the first Brazilian sugar reached Europe, and now it was cheap enough for ordinary people to aspire to enjoy it. Warfare, cane disease and weather might cause small fluctuations, but the price continued to fall. The fall in price was more than matched by the increased demand, and that demand was matched by a continued growth in the area under cultivation with sugar cane.

The sack of Antwerp in what is now Belgium, by Spanish forces opposing Dutch independence, led to the destruction of the refineries there and by 1600 the English, French and Dutch were all in the sugar refining business. The Antwerp workers dispersed, taking their knowledge with them to London, Amsterdam, Hamburg and Rouen, resulting in increased competition for raw sugar to feed the new refineries. All the same, the English were slow to begin growing sugar in their colonies. As Richard Ligon tells us, most of them started as growers of tobacco, cotton, indigo and ginger, along with cassava, plantains, beans and corn. This was the usual island pattern, with sugar only coming in later.

Barbados, for example, only started planting sugar in about 1640, and had a number of poor years, until the arrival of Dutch and Jewish refugees ejected from Pernambuco in northern Brazil. They provided the technical knowledge to make more and better sugar. The disruption in Brazil had also reduced the amount of sugar available in Europe, making this an excellent time for Barbados to adopt the new crop.

A simultaneous plus and minus was that Barbados had many smallholdings already cleared. This made it easy to plant cane, but as the best results financially came with a mill for every 40 hectares (100 acres) of cane, small farmers could not get capital, and their farms were quickly swallowed up by their larger neighbours. Many landless people joined the 1655 British invasion of Jamaica, and gained land there, but the surviving Barbadian planters were now rich and powerful, thanks to sugar.

Between 1663 and 1775, English consumption of sugar increased twentyfold, and almost all of it came from the Americas. Sugar was big business, and led to the first Molasses Act being passed in Parliament in 1733. It was set to last for five years, but it was regularly renewed, consolidated in the Sugar Act of 1764, and only repealed in 1792. This Act, in its various forms, set a duty of 5s. per hundredweight on sugar, 9d. per gallon on rum and 6d. per gallon on molasses brought into a British colony from a foreign source, while the importation of French produce into Ireland was forbidden. The result of the tax was to encourage wholesale smuggling of sugar and molasses into the thirteen British colonies in North America (and their eventual revolt). It seems not to have been worth the effort to smuggle sugar into England, however. In 1852, Captain Landman, late of the Royal Engineers, recalled an incident at Plymouth in 1796:

[We walked] towards the harbour, and on our way met an immense number of thin women proceeding with the utmost expedition, whilst all those we overtook, about equal in number, were large stout females, evidently waddling along with difficulty. On seeing these, Phillip explained that the latter were all wadded with bladders filled with Hollands gin, which they manage to smuggle under these dresses, whilst the others were thin and light, having delivered their cargoes at the waterside . . . everybody knew the trade they were engaged in.

Perhaps sugar was just too hard to carry, but more probably it was too bulky to repay the time, risks and effort, so people in Europe consumed taxed sugar and put up with it. Even with taxes, everybody had to have their sugar.

By 1675, England was seeing 400 vessels, each carrying an average of 150 tons of sugar, arriving from the colonies each year. France was exporting equally large amounts of sugar from its colonies. All sorts of arguments were proposed against the tax on sugar, from the suffering of the planters and their slaves to the welfare of Britain, but the French and British governments kept on taxing.

The hunger for sugar was by no means an English phenomenon. When Tobias Smollett travelled in France and Italy in 1766, he described tea at Boulogne: ‘It is sweetened all together with coarse sugar, and drank with an equal quantity of boiled milk.’ He recorded better Marseilles sugar at Nice, but complained that the liqueurs there were so sweetened with sugar as to have lost all other taste. He complained also of the flies, which apart from anything else, ‘croud into your milk, tea, chocolate, soup, wine, and water: they soil your sugar’. Later, Smollett referred to buying sugar and coffee in Marseilles, giving us the trinity of the sugar promoters: tea, coffee and chocolate, all needing to be sweetened.

Doctor Johnson also had something to say on the subject of the French way with sugar according to Boswell:

At Madame ——’s, a literary lady of rank, the footman took the sugar in his fingers, and threw it into my coffee. I was going to put it aside; but hearing it was made on purpose for me, I e’en tasted Tom’s fingers.

Although it has been recorded as replacing honey in recipes for chardequynce, a sort of jam or compote, as early as 1440, sugar only began to appear regularly in recipes about the mid-1700s. Mrs Hannah Glasse published her The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy in 1747, and the book revealed sugar as a standard item in the kitchen—one cake recipe calls for ‘three quarters of a pound of the best moist sugar’.

When Thackeray wrote of the England of the early nineteenth century in Vanity Fair, he used sugar grades to distinguish social classes. Here he describes Mr Chopper:

The clerk slept a great deal sounder than his principal that night; and, cuddling his children after breakfast (of which he partook with a very hearty appetite, though his modest cup of life was only sweetened with brown sugar), he set off in his best Sunday suit and frilled shirt for business, promising his admiring wife not to punish Captain D.’s port too severely that evening.

The purer white sugar that would satisfy others was out of the reach of a clerk, but tea and sugar had become essentials of life. Charles Dickens mentioned sugar 102 times, on thirteen of those occasions in the phrase ‘tea and sugar’, while rum rated almost 150 mentions. Dickens makes it clear in a scene in Nicholas Nickleby that it was not uncommon for a cook to expect tea and sugar to be provided in the terms of employment.

The habit of drinking tea was a key factor in saving lives when cholera reached Britain in the nineteenth century, because boiling water to make tea killed the germs in the water. The infamous Broad Street pump in London’s Soho, drawing water from a well lying beside a cesspit, killed most of the non-tea drinkers in the area before Dr John Snow made the link between the pump and cholera, and called for the removal of the handle on the pump.

Wherever the English went, whether aristocrat or commoner, tea and sugar went with them. In 1826, convicts in Australia had a weekly ration of 7 lb. meat, 14 lb. wheat and 1 lb. sugar; in 1830, shepherds and other farm employees were allowed 10 lb. meat, 10 lb. flour, 2 lb. sugar, and 4 oz. tea each week. In 1833 a teenager called Edward John Eyre set off to make his fortune in the Australian bush, with a quart pot, a little tea and sugar, and some salt.

On his first night, Eyre and his dray driver shared a glass of rum before settling down to sleep for the night under the stars. Within a decade Eyre would be winning fame as an explorer, a finder of paths across the trackless Australian landscape; within three decades he would be reviled by much of England and most of Jamaica as the man who hanged more than 400 former sugar slaves on Jamaica. In 1833 the teenage boy was an ordinary person, but sugar and rum were staples of life for an Englishman in the colonies.

SUGAR

Hazardous Properties: It is well known that sugar refiners face an industrial hazard which consists of an irritation to the skin; it may be a form of dermatitis. Bakers also experience a dermatitis due to sugar. Storage and Handling: Personnel who must work with this material continually and who are sensitive to it should wear protective clothing to avoid skin contact.

N. Irving Sax, Handbook of Dangerous Materials, New York, 1951