English verse is a succession of syllables. Some are strongly emphasized, some are not. The pattern of metre is set up by the way in which heavily stressed syllables are interspersed with more lightly stressed syllables. The metrical patterns are termed ‘feet’. The main types of feet are as follows.

The iamb: this consists of one lightly stressed syllable followed by one stressed syllable. ‘Revolve’, ‘behind’, ‘before’, ‘aloud’ are all iambs.

The trochee is the iamb reversed. It consists of one stressed and one lightly stressed syllable. ‘Forward’, ‘backward’, ‘rabbit’, ‘orange’ are all trochees.

These two metrical feet, iamb and trochee, each consist of two syllables. But it is possible to have three syllables in a foot, as follows.

An anapaest consists of two lightly stressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable. ‘Repossess’ and ‘understand’ are examples.

A dactyl is an anapaest reversed. It consists of one stressed syllable followed by two lightly stressed syllables. ‘Pulverize’ and ‘agitate’ are dactylic feet.

The intermediate pattern, when a stressed syllable is flanked fore and aft by two lightly stressed syllables, is called an amphibrach: ‘redouble’, ‘confetti’.

Such examples as are given here should not be taken to be fixed, as a mathematical quantity would be. They should be regarded rather as indicators. The weight of stress can vary appreciably according to context, especially when that context departs from a metrical norm.

What is a metrical norm? In order to form a line of verse, each foot is repeated several times. The more times the foot is repeated, the longer the line becomes.

It should be emphasized that one rarely comes across a line that is entirely anapaestic, or entirely dactylic, or entirely amphibrachic. Usually, with a line made up of trisyllabic feet, there is a mixture of patterns.

A dimeter is what we would call a line consisting of two feet. An iambic dimeter would be ‘The passive heart’. A trochaic dimeter would be ‘chimney sweeper’. One that is anapaestic is ‘at the end of the road’. The equivalent dactyl would be ‘Come along rapidly’ and the equivalent amphibrach would be ‘As midsummer flower’.

In practice this particular pattern tends to be mixed, as in the following start of an anonymous song of the sixteenth century:

Over the mountains

And under the waves,

Over the fountains

And under the graves.

The first and third lines are dactylic dimeters. The second and fourth lines, also dimeters, are amphibrachic, and docked of a final syllable.

The dimeter is rare, and the trimeter, in which three stressed syllables are in question, is scarcely less so. ‘The world a hunting is’ (William Drummond, 1585–1649) is an example of iambic trimeter. The trochaic equivalent is ‘Rose-cheeked Laura, come’ (Thomas Campion, 1567–1620), with the final syllable docked. An example of anapaestic trimeter is ‘As we rush, as we rush, in the train (James Thomson, 1834–82). A dactylic trimeter in a pristine state would be ‘merrily, merrily, merrily’, but the final syllable is usually docked.

Comparatively few poems of any worth have been written in very short lines. However, the American poet J.V.Cunningham (1911–85) was a master in this form of verse. Here is the poem from which an example of iambic dimeter, cited earlier, was culled. It is called ‘Acknowledgment’ and concerns the way in which an unimpressive life can be made meaningful in a literary text:

Your book affords

The peace of art,

Within whose boards

The passive heart

Impassive sleeps,

And like pressed flowers,

Though scentless, keeps

The scented hours.

More usually, short lines are variegated, in the manner of John Skelton (1460–1529). The mode is called ‘Skeltonics’, after him. His lyric ‘To Mistress Margaret Hussey’ begins:

Merry Margaret,

As midsummer flower,

Gentle as falcon

Or hawk of the tower.

The first foot of the first line is a docked dactyl, with a syllable elided from ‘Merry’. We know this is docked, or truncated, because the mode of the poem is couched predominantly in feet of three syllables; that is to say, trisyllabic feet. Predominantly these feet are amphibrachic dimeters—‘As midsummer flower’—though there are also truncated dactylic dimeters—‘Gentle as falcon’.

Modern instances of Skeltonics have been produced by Robert Graves (1895–1985), who was a great admirer of the older poet, and by Lilian Bowes Lyon (1895–1949). She has them as dimeters in her poem ‘Snow Bees’. This begins:

Trimeters displaying three sets of triple feet are used mainly for satirical purposes. There is little good poetry written in this pattern, but some that is entertaining. Winthrop Mackworth Praed (1802–39) uses an amphibrachic trimeter to celebrate the ‘season’. This was a period of balls and parties held in London each year in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and discontinued only in recent times. It acted as a marriage mart for ‘débutantes’; that is to say, young ladies thought socially acceptable enough to have been introduced to the reigning monarch. (‘Gay’ here has its original use of ‘merry’ or ‘blithe’.)

Good-night to the Season! ’tis over!

Gay dwellings no longer are gay;

The courtier, the gambler, the lover,

Are scattered like swallows away.

Notice that the alternate lines are docked of a syllable.

However, the shorter line that is most frequently used is not the dimeter or the trimeter but the tetrameter. The tetrameter is a four-stress line, whose ‘beat’ is provided by the syllables that bear a heavy stress, as distinct from those that are lightly stressed.

The greatest variety is provided by the iambic tetrameter. This was the chosen mode of two major poets, Andrew Marvell (1621–78), who was best known for his prose in his own time, and Jonathan Swift (1667–1745), who is best known for his prose in ours.

The range of which this metrical pattern is capable may be seen in the following examples, First, there is the beginning of Marvell’s poem ‘To his coy mistress’:

Had we but world enough, and time,

This coyness, lady, were no crime.

We would sit down and think which way

To walk and pass our long love’s day.

Then there is a poem on what seems to be a quite different topic, Swift’s ironic elegy or verse obituary for himself, ‘Verses on the Death of Dr Swift’:

The time is not remote, when I

Must by the course of nature die:

When I foresee my special friends,

Will try to find their private ends.

Marvell’s love poem rises to a metaphysical contemplation of death, still in this same metre:

But at my back I always hear

Time’s winged chariot hurrying near:

And yonder all before us lie

Deserts of vast eternity.

The poem by Swift, though primarily satirical, has passages of meditation:

Indifference clad in wisdom’s guise

All fortitude of mind supplies:

For how can stony bowels melt,

In those who never pity felt?

The trochaic tetrameter, on the other hand, is capable of no such variegation. Swift is probably the greatest master of this limited metre, and he uses it mainly to express indignation. In ‘The Legion Club’, he gives his view concerning the Irish Parliament of his day:

Let them, when they once get in,

Sell the nation for a pin;

While they sit a-picking straws,

Let them rave of making laws;

While they never hold their tongue,

Let them dabble in their dung.

As with those in the trimeter, the triple feet employed in the tetrameter are chiefly useful in the lighter kind of satire. Matthew Prior (1664–1721) has a poem called ‘A Better Answer’, addressed to his presumed mistress, in which he whimsically discredits the truth of another poem he has written, apparently to some other young lady:

Dear Chloe, how blubbered is that pretty face,

Thy cheek all on fire, and thy hair all uncurled,

Prithee quit this caprice and, as old Fa (staff savs,

Notice that the final foot in each line is, as in earlier examples of amphibrachic metre, docked of a syllable.

So far, the argument of this chapter has been couched in terms of metre. But metre is by no means the whole of prosody, as the study of the art of versification is called. In fact, many practising poets would question whether problems of metre have much to do with ‘art’. They are primarily a matter of craft: the kind of dexterity that, as the mastermetrist Seamus Heaney (b. 1939) says, wins competitions in the weekly magazines. One certainly needs craft in order to write a poem, but a good deal else is necessary. One needs that set of faculties which Seamus Heaney calls ‘technique’: ‘the whole creative effort of the mind’s and body’s resources to bring the meaning of experience within the jurisdiction of form’. We can use this differentiation between craft and technique in seeking to indicate what, more than metre, goes to creating the movement of a poem.

Metre is a blueprint; rhythm is the inhabited building. Metre is a skeleton; rhythm is the functioning body. Metre is a map; rhythm is a land.

The forms I have described in metrical terms can hardly ever be found practised with the simplicity that those terms suggest. What, more than metre, does a poem have? It has variegation of verse movement. The poet may indeed begin with a metrical plan. But that plan is realized in terms of variations; variations on a metrical norm.

This can be seen even in the examples quoted so far. There are syllables docked from the ends of lines, as in Praed’s ‘Good-night to the Season’, already glanced at, and Priors ‘A Better Answer’. There are role-reversals, as when dactyls—‘Gentle as’—stand in for amphibrachs—‘Or hawk of’. But, more subtle than that, we have variegation of stress itself.

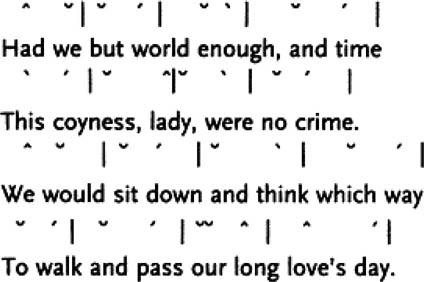

So far, we have been proceeding on the assumption that there are only two degrees of emphasis in syllables: stressed and lightly stressed. There are, in fact, four recognizable levels of emphasis: primary stress, secondary stress, tertiary stress and weak stress. Using a system developed in 1951 by the linguists George L.Trager and Henry Lee Smith, we can represent primary stress (heavy) with ΄; secondary stress (medium) with ^; tertiary stress (medium-light) with `; and weak stress (light) with.

This mode of representation may serve as a way of indicating the difference in rhythmic structure between verse patterns that seem metrically identical. The end of a foot may be represented with a bar, thus: |.

Earlier on, the iambic tetrameter was characterized as offering a greater range than the metres previously considered, the dimeter and the trimeter. Four beats are better than two or three, at least so far as variety is in question. If we take the two quotations from

Marvell s ‘To His Coy Mistress’, the point can be made by utilizing the Trager-Smith notation:

The first foot of the first line, when we come to look at it rhythmically rather than metrically, is inverted. That is to say, the iambic norm would lead us to expect a light stress on the first syllable, ‘had’, and a heavier stress on the second syllable, ‘we’. The reverse is true. Yet the stress in this first foot is not the heaviest you can get. The main emphasis in the line is on ‘world’ and on ‘time’, and appositely so, since these—rather than persuading one’s mistress to bed—are the main themes of the poem. Therefore these two words take the heaviest stresses, the primary stresses.

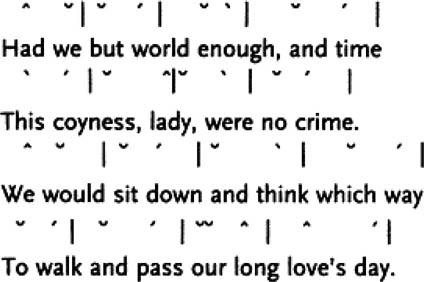

The poem builds up its preoccupation with ‘world’ and ‘time’ to this extent, that sixteen lines further on it has gravitated into a sense of urgency regarding death. The metre is the same; the rhythmic structure shows some interesting differences:

There is a greater sense of speed in this passage, compared with the previous one quoted. This is in part accomplished by there being a greater proportion of light stresses to those that are heavy, and more of those supposedly heavy stresses are secondary and tertiary than is the case with the previous example. The line ‘Time’s winged chariot hurrying near’, in consequence, really does hurry: the rhythm acts out the sense.

In the next line, ‘And yonder all before us lie’, there is a noticeable pause between ‘yonder’ and ‘all’, and this has been marked with ¶. The effect is to allow a medium-light stress on ‘all’, so as not to slow the rhythm up too much. This kind of pause plays an important part in versification. In fact, there is almost always a pause mid-line called a caesura. Usually it is too slight to require a special marking. Further, the end of every line in every poem has a pause. Again, it is not usually marked as a separate item. However, it is this that, in the present instance, allows the weight of ‘lie’, with its heavy stress, to continue without merging into the next line. It is in this way that we can have a heavy stress on ‘lie’ and a heavy stress on the first syllable of ‘Deserts’ without destroying the basic metre. The effect is as though a silent but noticeable equivalent of had been interposed.

In this final line of the passage cited, the disposition of stresses allows the rhythm to trail off, as it were, into the deserts. After the first, each successive one of the so-called heavier stresses in this line of verse—‘Deserts of vast eternity’—is in effect lighter than the last. After the heavy stress on the first syllable of ‘Deserts’, there is a further heavy stress on ‘Vast’, but then there is a medium stress on the second syllable of ‘eternity’, and a medium-light stress on the fourth syllable. This is in contradistinction to what happened in the first four lines quoted from ‘To His Coy Mistress’, where every line ended with a heavy stress, thus slowing the rhythm down. This contradistinction accounts for the difference in rhythm between the two quatrains, or groups of four lines, even though the metre is ostensibly the same.