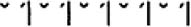

The heroic couplet resembles a blank verse line, inasmuch as the basic metre runs:

The difference is that the heroic couplet rhymes in pairs.

The rhyme scheme is notated as a a b b c c d d. Each individual letter betokens a new rhyme. Any coincidence of letters betokens the same rhyme, as follows:

When I consider life, ’tis all a cheat; a

Yet, fooled with hope, men favour the deceit; a

Trust on, and think tomorrow will repay: b

Tomorrow’s falser than the former day; b

Lies worse, and, while it says, we shall be blest c

With some new joys, cuts off what we possessed. c

Strange cozenage! None would live past years again d

Yet all hope pleasure in what yet remain; d

And, from the dregs of life, think to receive, e

What the first sprightly running could not give. e

I’m tired with waiting for this chemic gold, f

Which fools us young, and beggars us when old. f

This is from Aurung-Zebe, by John Dryden (1631–1700), and one may feel surprised to find that it is a play. It is, in fact, a heroic tragedy; one akin to classical epic, whose heroes strike self-consciously noble attitudes. Hence the name of the metre: heroic couplet.

The mode of sententious moralizing, of which this is a fine example, rose in the early seventeenth century and dominated English poetry, throughout that century and its successor. Especially between 1640 and 1750, or thereabouts, it was how one wrote a long poem, dramatic or not.

The form of the heroic couplet was invented by Geoffrey Chaucer (1340–1400), often, and for other reasons, termed ‘the father of English poetry’. It thus antedates the invention of blank verse by some 150 years. Chaucer’s first exercise in the metre seems to have been his Legend of Good Women, which is usually dated to the mid-1380s. This is how one of its Prologues (there are two different versions) begins:

A thousand times have I heard men tell

That there is joy in heaven and pain in hell,

And I accorde well that it is so;

Yet natheless, yet wot I well also

That there is none dwelling in this country

That either hath in heaven or hell y-be,

Ne may of hit none other wayes witten

But as he hath heard said or found it written.

(‘Natheless’ is the same as ‘nonetheless’; ‘wot’ is the same as ‘understand’, and so is ‘witten’; ‘hit’ is ‘it’.)

The difference between this and the preceding passage from Dryden is that Chaucer sounds certain vowels that would not have been sounded in Dryden’s time, much less in our own. These vowels are here put into bold print. The main vowel to receive this treatment in Chaucer, here as elsewhere, is e: ‘A thousand times have I heard men tell’. Without that kind of sounding, the line would not scan as part of a heroic couplet.

Yet there is no agreement as to how Chaucer used this sounded e. The vowel seems to have been sounded or not sounded, according to whether a line would or would not scan without it. The device seems similar to the added syllable we find in this same passage: That either hath in heaven or hell y-be’. There is no grammatical necessity for the ‘y-’ here. It is just that, without the added syllable, the line would not scan.

Soon after Surrey’s translation of Virgil, blank verse became a persuasive rival to the heroic couplet. It moved into most forms of drama. Yet the heroic couplet held its own as a vehicle for meditative and satiric poetry and, until Miltons example took hold some half-century after his death, as a vehicle for narrative poetry also.

One of the stories that circulate about English poetry is that the couplet at one point was very rough and was civilized by Dryden and other great poets of the late seventeenth century. It would be truer to say that, just as blank verse has three major varieties, so the heroic couplet has two. One of them can be associated with Dryden’s greatest successor in the satiric mode, Alexander Pope (1688–1744). The famous poet, beset by fans who wish him only to look at their own verse, begs his servant to keep away from his secluded study these frenzied admirers:

Shut, shut the door, good John! fatigued, I said,

Tie up the knocker, say I’m sick, I’m dead.

The dog-star rages! nay ‘tis past a doubt,

All Bedlam, or Parnassus, is let out.

Fire in each eye, and papers in each hand,

They rave, recite and madden round the land.

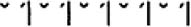

That is the beginning of Pope’s Epistle—that is to say, a formal letter—to his friend Dr Arbuthnot. The ‘dog-star’ is Sirius, part of the constellation Canis Major (larger dog), and associated with the heat of August when dogs and poets go mad. Bedlam was a well-known lunatic asylum of the day, which the poet equates with Parnassus, the cradle of the Muses, who inspired the arts. It is a technically brilliant piece of verse, as anyone who wishes to write heroic couplets will discover in undertaking that particular metrical form. There is almost as much variegation of rhythm as you would find in a piece of dramatic blank verse:

It may not be as varied as Macbeth, but it is far from adhering to a metrical norm.

Even so, we cannot help but be conscious of the rhymes lining themselves up like a double row of soldiers. For all the comparative freedom of rhythm, each pair of lines tends to be a closed entity.

Now this is not owing to the tyranny Pope exerted over the heroic couplet. Nor is it part of some civilizing process. There were couplets more metrically based than this being written over a hundred years earlier. The following is from a book of poems called Bosworth Field by Sir John Beaumont (1583–1627). It is the beginning of an elegy on his son:

Can I, who have for others oft compiled

The songs of death, forget my sweetest child,

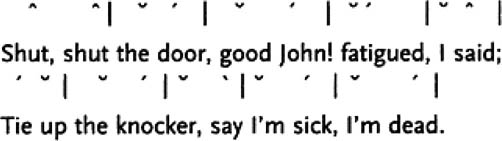

Which like the flower crushed with a blast is dead,

And ere full time, hangs down his smiling head.

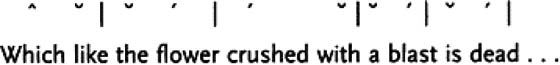

Line 3 seems slightly less regular than the others. ‘Flower’, though, would have been pronounced as a single syllable. The lines are, that is to say, related to the metrical norm:

No doubt what is behind this is another poem, also lamenting the death of a son, by a poet Sir John Beaumont greatly admired; at least, he wrote ‘a song of death’ in his honour. The poet in question is Shakespeare’s great contemporary Ben Jonson (1572–1637); the poem, ‘On my first son’:

Farewell, thou child of my right hand, and joy;

My sin was too much hope of thee, loved boy,

Seven years thou wert lent to me, and I thee pay

Exacted by thy fate, on the just day.

O, could I lose all father, now. For why

Will man lament the state he should envy?

To have so soon ’scaped world’s, and flesh’s rage,

And, if no other misery, yet age!

Rest in soft peace, and, asked, say here doth lie

Ben Jonson his best piece of poetry.

For whose sake, henceforth, all his vows be such,

As what he loves may never like too much.

This is a poem much of whose appeal lies in control; the way in which a powerful emotion is contained in a set of heroic couplets, and does not overflow the line.

But that is only one variety of this particular metre. The same poet could write, in narrative vein:

It was the day, what time the powerful moon

Makes the poor Bankside creature wet its shoon,

In its own hall; when these (in worthy scorn

Of those, that put out monies, on return

From Venice, Paris, or some inland passage

Of six times to, and fro, without embassage,

Or him that backward went to Berwick, or which

Did dance the famous Morris, unto Norwich)

At Bread Street’s Mermaid, having dined, and merry,

Proposed to go to Holborn in a wherry.

This is an extract from Jonson’s scabrous poem ‘On the Famous Voyage’; the voyage in question being through the poet’s guts. ‘Shoon’ is an archaic plural for shoes; ‘embassage’ is a commission or message; ‘backward to Berwick’—some person, not identifiable, must have attempted the feat of walking backwards, presumably from London, to the Scottish Border town of Berwick; ‘the famous Morris’—the comedian Will Kemp danced from London to Norwich in 1599; ‘wherry’—rowing-boat, designed to carry passengers on the river.

Two characteristics distinguish these heroic couplets from the ones used in Jonson’s poem on his son, and indeed those used by Dryden, Pope and Beaumont. One is the extent to which the verse employs enjambment; that is to say, the extent to which the lines overflow their metrical boundaries:

It was the day, what time the powerful moon >

Makes the poor Bankside creature wet its shoon, >

In its own hall…

The other characteristic is a marked tendency towards parenthesis; that is, the turningaside from the main argument to pursue some subordinate theme. This turning-aside is usually marked by brackets at the opening and the closing of the parenthesis:

when these (in worthy scorn >

Of those, that put out monies, on return >

From Venice, Paris, or some inland passage >

Of six times to, and fro, without embassage, >

Or him that backward went to Berwick, or which >

Did dance the famous Morris, unto Norwich).

Without the parenthesis, the argument would read:

It was the day, what time the powerful moon

Makes the poor Bankside creature wet its shoon,

In its own hall; when these

At Bread Street’s Mermaid having dined, and merry,

Proposed to go to Holborn in a wherry.

The parenthesis puts the reader aside from the main theme, but it also brings the reader back, and that is a characteristic of the second variety of heroic couplet.

A master of this variety was perhaps the most neglected poet of any importance in English, William Chamberlayne (1619–89). It may well be his tendency towards parenthesis, and parenthesis within parenthesis, accompanied by a very free handling of enjambment, that has brought about this neglect. But these characteristics are apposite to his theme, which is the fantastic set of adventures undergone by the knight Argalia and his love, Pharonnida. The characteristics in question are also apposite to Chamberlayne’s style, which is an admixture of beauty with strangeness.

Here is an extract from Chamberlayne’s long poem Pharonnida. The present author has taken the liberty of marking in bold type with (and) the opening and closing of the main parentheses, and with [and] the opening and closing of those subordinate parentheses contained within the main ones. Pharonnida is dreaming of a future life with her lover:

Whilst thus enthean fire did lie concealed

With different curtains, (lest, [by being revealed,]

Cross fate, [which could not quench it,] should to death

Scorch all their hopes, burned in the angry breath

Of her incensed father)—whilst the fair

Pharonnida was striving to repair

The wakeful ruins of the day, (within

Her bed, [whose down of late by love had been

Converted into thorns],) she (having paid

The restless tribute of her sorrow), staid

To breathe awhile in broken slumbers, (such

As with short blasts cool feverish brains; [but much

More was in hers])—A strong pathetic dream,

(Diverting by enigmas Nature’s stream,

[Long hovering through the portals of her mind

On vain phantastic wings],) at length did find

The glimmerings of obstructed reason by

A brighter beam of pure divinity…

(‘Enthean’, by the way, is a rare word meaning ‘inspired by an indwelling god’.) There is no reason, other than time and space, to stop quoting at this point. The sentence continues for several more lines in which, as in the ones already quoted, each idea gives rise to other ideas, and parenthesis grows out of parenthesis.

That forgotten master strongly influenced the poet who perhaps was the most notable exponent of this parenthetical variety of couplet: John Keats (1795–1821). He goes one step further than Chamberlayne, in that his sense hardly ever matches up with the rhyme scheme of the couplet. Thus, to the tendency towards parenthesis, and the persistent enjambment, Keats adds the effect of directing the sense not with the couplet, as one would find in Pope, but against it. The following passage, from ‘Lamia’, begins, therefore, in mid-couplet, seeming to ignore the tendency of the rhyme. Lamia, a snake who has the superficial appearance of a woman, is making preparations for her bridal feast. The style, extravagant and exotic, matches its arcane subject:

She set herself, (high-thoughted,) how to dress

The misery in fit magnificence.

She did so, but ’tis doubtful how and whence

Came, and who were her subtle servitors.

About the halls, and to and from the doors,

There was a noise of wings, till (in short space)

The glowing banquet-room shone with wide-arched grace;

A haunting music, (sole [perhaps] and lone

Supportress of the fairy-roof) made moan

Throughout, (as fearful the whole charm might fade).

The passage finishes, as it began, in mid-couplet. The whole metre is very plastic, with its run-on sentences, its loose syntax, its refusal to be contained within the couplet form. Nevertheless, the chime of the couplets is heard as a kind of counterpoint to the sense, and it is in this way that a modern poet would use this metre. The modern poet would, on the whole, prefer the Keatsian to the Popeian variety of couplet.

The present author, meditating on the threatened loss of his eyesight, quite instinctively utilized this freer mode of couplet in a poem called ‘The Good Doctor’:

Doctor, the nurses fly you. That quick flash

Of wit or spectacles would pink the flesh

Of blonde Miss Winfield or the tub of lard

You had before her, as it scores my hide.

For I flinch too, and ‘Steady now’ you say

Thrusting a lump of coke into my eye

(At least it feels like coke) ‘you need control.’

I do indeed, if I’m to blink at will,

Flex the eye muscles, peer into the sun,

And take my painful medicine like a man.

‘Mere sensation,’ you say—but how it sears,

My vision, subject to your probes and flares!

And yet you are a good doctor. I was blind,

You gave me sight, mapped the scar-tissue, stemmed

The blood that wept behind my retina,

Fading my townscape green. Every cure

Is moral victory on the optic plane,

And how you, solemn doctor, laughed again

When I deciphered words a child could tell

From your illuminated board. Will?

Perhaps—perhaps encouraged. Maybe I saw

Because there was someone to see, someone to care.

This not only goes in for enjambment and parenthesis but utilizes pararhyme, the nature of which will be defined in the next chapter. Yet the metre here would certainly be considered formal compared with much verse of the later twentieth century.

It will be assumed from the foregoing argument that the heroic couplet, both in its Popeian and in its Keatsian varieties, is capable of range and flexibility. The reason why it lost ground steadily to blank verse is that it is only partially capable of dramatic effect. If we return to the couplet as used by Dryden, we shall be able to recognize both its virtues and its limitations.

There is no doubt that Dryden was a heroic poet. His translation of the Aeneid in couplets is far superior to that of Surrey in blank verse. The point can be readily made if we look at Dryden’s version of the same passage as was quoted at the beginning of the previous chapter in the version of Surrey. Dryden has:

All were attentive to the godlike man,

When from his lofty couch he thus began:

‘Great queen, what you command me to relate

Renews the sad remembrance of our fate:

An empire from its old foundations rent

And every woe the Trojans underwent…’

This is crisp and business-like, and was famous in its time—as the Paradise Lost of John Milton most certainly was not. Why, then, did taste in narrative move away from the heroic couplet of Dryden and towards the blank verse of Milton?

The answer can be seen if we look at Dryden’s plays. He made attempt after attempt at heroic tragedy, but these efforts cannot be acted now. They may sustain an isolated speech, like the one from Aurung-Zebe, quoted at the beginning of this chapter. But it is when they seek to render dialogue that the limitations of heroic couplets, at least in their Popeian variety, make themselves felt.

In the first scene of The Conquest of Granada, the Moorish families, Zegry and Abencerrago, confront each other in warlike posture:

HAMET ’Tis not for fear the combat we refuse,

But we our gained advantage will not lose.

ZULEMA In combating, but two of you will fall;

And we resolve we will despatch you all.

OZMYN We’ll double yet the exchange before we die,

And each of ours two lives of yours shall buy.

(ALMANZOR enters betwixt them, as they stand ready to engage.)

ALMANZOR I cannot stay to ask which cause is best;

But this is so to me, because opprest

Almanzor, a stranger to the conflicting parties, instinctively joins the weaker side. However, there is a dichotomy between the would-be heroic activity and the pernickety numbering of the factions: ‘but two of you will fall’, ‘We’ll double yet the exchange’. This mock-precision or gesticulation towards wit seems to be latent in this variety of the couplet, and produces an effect at variance with the posturing. One can only say that the action would have been happier in blank verse.

Is the heroic tragedy capable of revival now? Ostensibly, it would seem not. Yet there have been attempts to translate its counterpart, the formal comedy of the French playwright Molière (1622–73), into couplets. The most brilliant of these is that of Richard Wilbur (b. 1921). Here is M.Orgon, back from the country, being told sad news of his wife but remaining besotted with his favourite, Tartuffe, after whom the play in question is named:

ORGON Has all been well, these two days I’ve been gone? How are the family? What’s been going on?

DORINE Your wife, two days ago, had a bad fever, And a fierce headache that refused to leave her. ORGON Ah. And Tartuffe?

DORINE Tartuffe? Why, he’s round and red, Bursting with health, and excellently fed. ORCON Poor fellow!

DORINE That night the mistress was unable To take a single bite at the dinner table. Her headache-pains, she said, were simply hellish. ORGON Ah. And Tartuffe?

DORINE He ate his meal with relish. And zealously devoured in her presence A leg of mutton and a brace of pheasants.

This suggests that the Popeian couplet is still alive for satiric purposes. It would, however, take a very unusual talent to employ the old form as adroitly as this, and the result might be more peculiar than poetic. Wilbur’s rhymes are certainly more far-fetched than any Dryden and Pope would have approved, and this is necessary to maintain flexibility: ‘fever’/‘leave her’; ‘presence’/ ‘pheasants’. There is also a degree of indecorum in the diction: ‘simply hellish’ is a 1920s kind of middle-class slang.

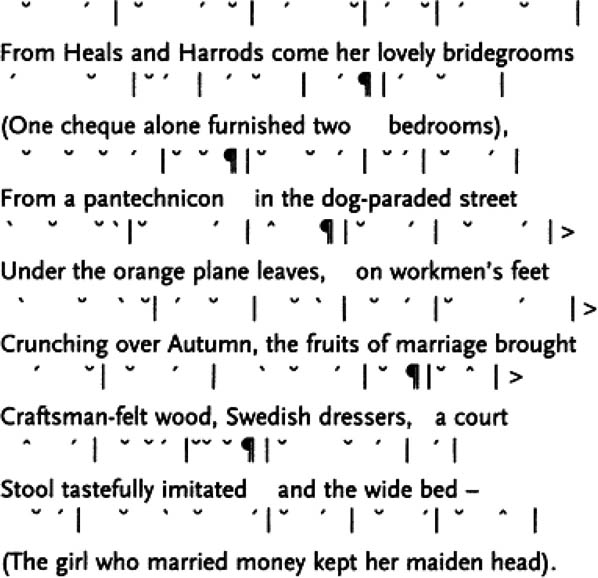

Such liberties as these are probably necessary if any version of the couplet is to be used in modern times. Peter Porter (b. 1929), perhaps the dominant satirical poet in mid-century Britain, has a similar fund of resource in adopting the metre. His rhythm is freer than that of Wilbur. While his are undoubtedly couplets, one could use the term ‘heroic’ only with a degree of qualification. Porter does indeed set up an iambic norm in the opening lines. But he then proceeds to flout that norm by adding lightly stressed and medium-lightly stressed syllables, to the extent that some lines could only dubiously be scanned as pentameters. It creates a kind of lurching effect, very much at one with the theme of ‘Made in Heaven’. This is a scathing satire on the débutante who marries for prestige and money, much as she would be tempted by goods displayed in the then fashionable stores, Heals and Harrods:

This is a swashbuckling rhythm, always threatening to turn into hexameters; that is to say, six-stress lines. But, for a number of reasons, hexameters are always unstable in English, and little of merit has been written in them. In any case, there is a basic five-stress rhythm pulsing through this poem. It is established in the opening lines, and sustained by providing extra syllables of medium-light (rather than medium) stress.

This loose (rather than rough) five-stress rhythm is in the tradition of a number of past satirists, masters of invective, such as John Donne (1572–1631) and John Marston (? 1575–1634). The latter, indeed, Peter Porter has celebrated as an exemplar in a satirical poem appreciably finer than the one which has just been quoted, effective though that is. But ‘John Marston Advises Anger’ is written not in couplets, but in Porters own highly individual blank verse. This suggests that, even for satire in modern times, metre in couplets has limited possibilities.

If the Keatsian couplet survives to an extent, the Popeian variety has gone, probably for ever. Its formality cannot accommodate the indecorous speech patterns of our time without putting the language under a measure of constraint. Any attempt in that direction would be likely to look as though it were pastiche. The style would echo previous practitioners too obviously, and be an invocation of the past rather than a voice emanating from the present. It therefore follows that what affects the couplet in our period also variegates use, in any metre, of rhyme.