Chapter One

The Two Protagonists

The City of Constantinople

It is not unusual, in the annals of history, for the fall of a city to be bound up with the destruction of a nation. Yet how many times in the long history of the human race has the fall of a city heralded the end of an entire civilization, and one that had exerted a significant influence on the surrounding world over the course of many centuries? Furthermore, how many such occurrences can be pinpointed not only to the exact year, but to the exact month, day, even hour? Constantinople is unusual because we know with certainty not only the day of its death, but the day of its birth as well.

This city on the Bosphorus Strait was known as Byzantium until May 11th, 330 C.E., when it took the name Constantinopolis (“The City of Constantine”) in honor of its founder, the Emperor Constantine. For 1,123 years it served as the capital of the Greek-speaking Roman Empire, also known as the “Eastern Roman Empire” or the “Byzantine Empire.”

In these pages we will use the anglicized name “Constantinople.” This is fitting in a sense because during the millennium or so of its flourishing, the city was known by a number of names other than the “Constantinopolis” used in Greek and Latin. Every ethnic group that had any connection with the city pronounced the name in its own way. The Italians, for example, who had a very close relationship with the city during its final years, called it “Constantinopoli.” The current official name of the city, “Istanbul,” is the Turkish variation on “Constantinopolis,” but one so altered by the passage of time that its etymology is difficult if not impossible to guess.

Similarly, “Adrianopolis” is known in modern Turkish as “Edirne.” When Constantinople fell, however, Adrianopolis (“The City of Emperor Hadrian”) had already been the Ottoman capital for over a hundred years, so referring to it here by its Greek or Latin name would not be quite appropriate. At the same time, though, since not even the Turks of the time had yet begun to call the city “Edirne,” for the sake of consistency let us refer to it by the rendition that would be most congenial for us, Adrianople.

The rapid development of Constantinople, also called “New Rome,” was quite enough to draw the attention of the neighboring peoples of the time, all the more so because the Western Roman Empire was in decline. Situated where Europe meets Asia, the city was destined from birth to become the capital of the Mediterranean world.

This “New Rome,” however, was completely different from the Rome to the west in one important way. Eastern Rome was an empire born with Christianity as its defining constituent. The cloak worn in public by the emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire was not purple, but crimson. The Christian church had made purple, which had been the color of the ancient Roman emperors, the color of mourning—in other words, the color of death.

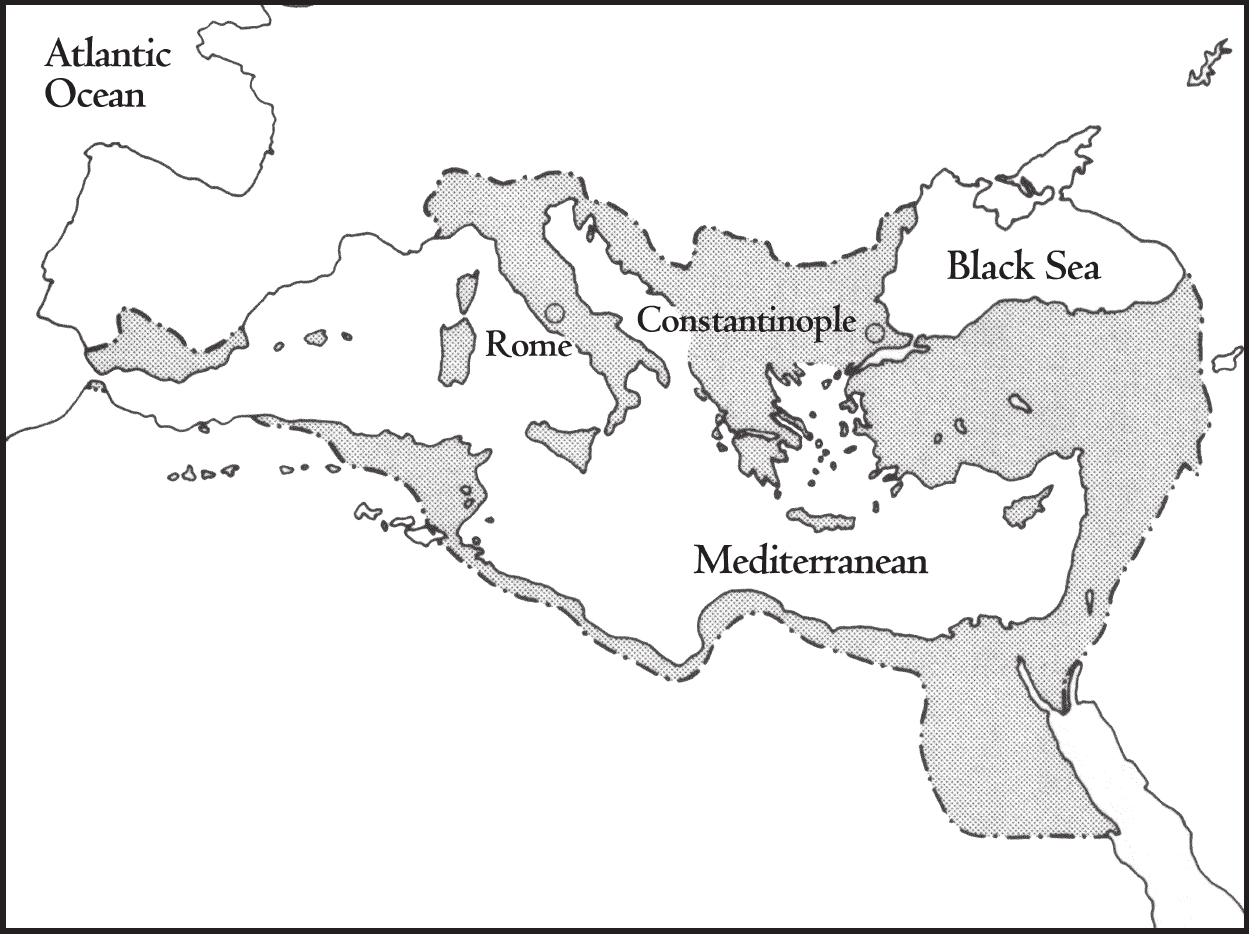

Although it is said that when Eastern Rome was founded in the fourth century it was already a more vibrant society than western Rome, in the final analysis it didn’t actually become the capital of the Mediterranean world until the original Rome met its ruin in the late fifth century. Less than a century after that, in the mid-sixth century, the Eastern Roman Empire’s sphere of influence reached its greatest extent. Although it didn’t match the ancient Roman Empire at its zenith, the Byzantine Empire under Emperor Justinian extended from the Straits of Gibraltar in the west to Persia in the east, from the Italian Alps in the north to the upper Nile in the south. (Map 1)

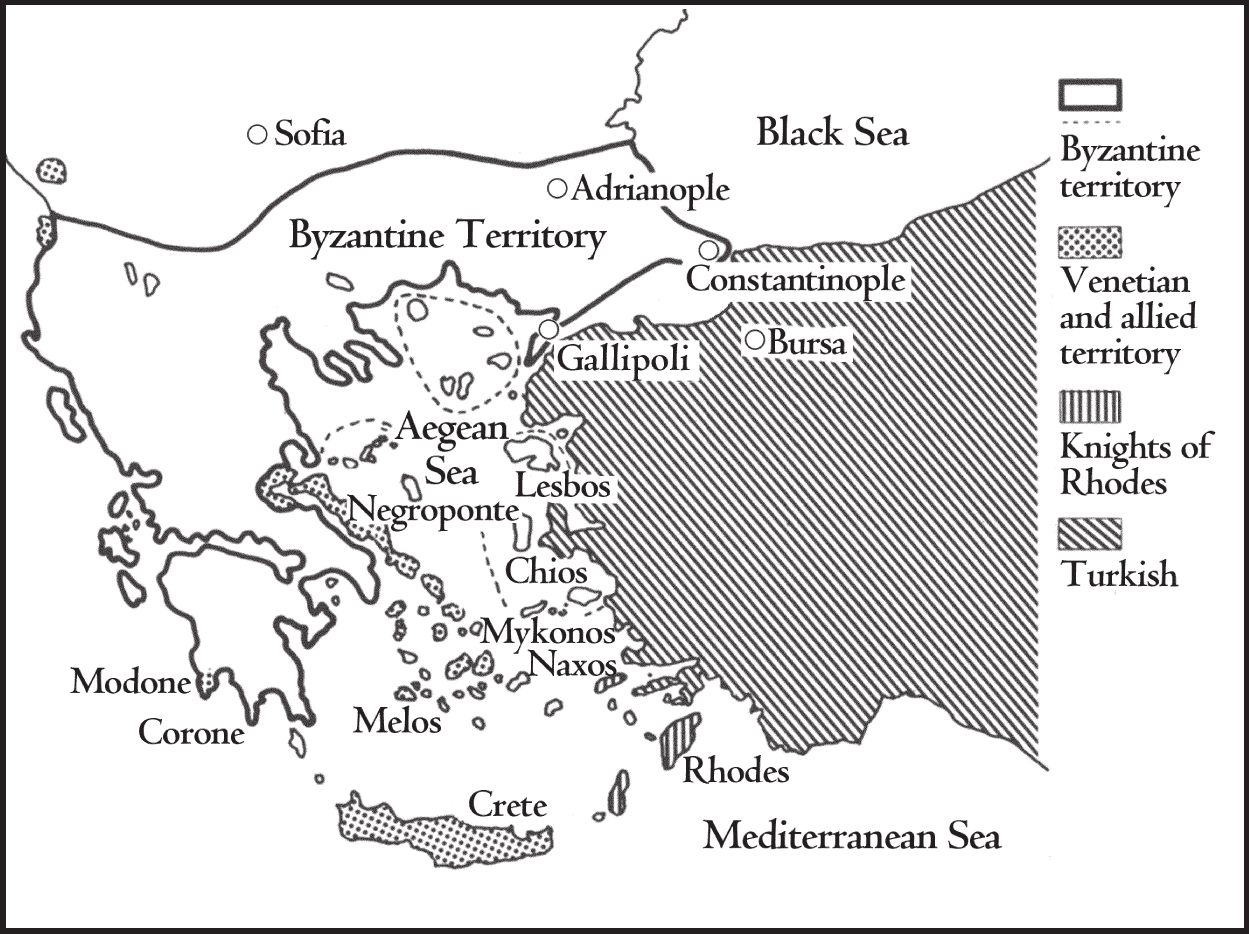

By the time the Crusades began in the 11th century, however, the empire had diminished considerably. The Byzantine Empire had become the base of the Greek Orthodox Church, whose doctrinal disputes with the Catholic Church had led to schism, and so its allegiances during this period of conflict between the Christian powers of the West and the Islamic forces in the East were not completely clear. It was during this time, as well, that the Byzantines lost control of the eastern Mediterranean Sea to the maritime city-states of Genoa and Venice. (Map 2) With such a state of affairs, it was only a matter of time before the empire was lost. The final push came with the Fourth Crusade in 1204, which also saw the founding of the Latin Empire. During this period only the Nicaean Empire, which had been founded in Asia Minor by exiles fled from Constantinople, kept the bloodlines of the Eastern Roman Empire alive.

The Byzantines were able to regain Constantinople after a mere sixty years, but to their great misfortune an archrival to the east continued to grow in size and strength in the meantime: the Ottoman Turks, who were consolidating their strength in the Anatolian plain. For the next century the Byzantines suffered a string of defeats. It is the guiding principle of history that all that prospers must eventually decline, but even so, the debilitation of the Byzantine Empire was notably precipitous. (Maps 3 and 4)

As the Turks crossed the Bosphorus Strait and conquered one European holding after another, the once-glorious Byzantine Empire was reduced to nothing more than Constantinople, its environs, and a portion of the Peloponnese peninsula. The Aegean Sea to the south was firmly in the grip of the maritime city-states of Venice and Genoa, each of which had a population of no more than 200,000.

During the Byzantine Empire’s flourishing between the sixth and tenth centuries, the population of Constantinople and its outskirts was said to have been around a million. By the beginning of the fifteenth century, it had fallen to less than a hundred thousand. The population density in the city proper was lower than that of either Venice or Genoa. Furthermore, the Italians of the time had given birth to Renaissance civilization and made coolheaded, rational thinking their trademark. To them, the Byzantines—who would not separate the church, whose affairs are spiritual, from the state, whose affairs are temporal—were a collection of medieval-minded irrationalists, prone to superstition, whose only interest was in religious sermons and who completely lacked the active and cooperative spirit absolutely essential to the efficient administration of a community.

Physically surrounded by the Turks, militarily negligible, economically at the mercy of the trading nations of Western Europe, the Byzantine Empire of the fifteenth century was led, coincidentally, by a man who shared the name of the city’s founder: Constantine XI. This emperor, who would be the Eastern Roman Empire’s last, was a physical embodiment of the elegant, dying civilization he oversaw: a refined, 49-year-old gentleman with a tranquil disposition who revered honor above all. Twice married and twice widowed, he had no children.

(Map1) The Byzantine Empire in Justinian’s times, ca. 565 C.E.

(Map2) The Byzantine Empire during the Crusades, 11th century

(Map3) The East Mediterranean, distribution of power in 1340

(Map4) The East Mediterranean, distribution of power in 1402

It was Emperor Constantine’s charge to defend the city of Constantinople, symbol of the Byzantine civilization that had imbibed the influence of the Orient as well as that of classical Greece and Rome, while still maintaining its distinct individuality. His opponent would be a young Turkish man who had just turned twenty years old.

Sultan Mehmed the Second

It is a given that, around the year 1300, nobody was paying any attention at all to the Ottoman Turks who had begun to consolidate their power at that time in the Anatolian plain in Asia Minor. Within 28 years, however, the Turks would go on to conquer the city of Bursa near the Sea of Marmara. With the very formidable Mongol Empire to the east and the weakened Byzantine Empire to the west, it was natural for this nomadic people to choose to expand westward. The Turks made Bursa their capital. Asia Minor was now completely within their control.

But this wasn’t enough to satisfy them. Their march west continued, and in 1354 they captured Gallipoli. Situated on the shore of the Dardanelles, Gallipoli was not in Asia: it was very much a part of Europe, even if only at its periphery. The fall of Gallipoli gave the Turks control of the strategic stretch of land running from the Dardanelles, through the Sea of Marmara, all the way to Constantinople. This was not something that would go unchallenged, either by the Byzantine Empire from whom the city was taken, or by the Western city-states who passed through those waters in order to conduct trade with Constantinople and cities on the Black Sea. The first reports of the menace presented by the rising power of the Turks appeared in the Republic of Venice, which had the most comprehensive information network at the time, during that same year 1354.

The Byzantine Empire didn’t have the forces to repel the invaders on its own, while Venice and Genoa were locked in internecine squabbles; the Ottomans proceeded steadily into the Balkans and the chance to stop them quickly slipped away.

1362 fall of Adrianople

1363 castle at Philippopolis captured

These two conquests put all of Thrace in Turkish hands. At the end of these two years they moved their capital from Bursa on the Asian side to Adrianople on the European side. There could be no clearer indication than this that they intended to continue their march westward. Neighboring Bulgaria, Macedonia, and the Byzantine Empire itself were suddenly jolted. Both Macedonia (officially under Byzantine rule) and Bulgaria became vassal states of the Ottomans, forced to pay annual tribute and to provide troops. The Byzantine Emperor not only had to pay annual tribute to the sultan, but also had to lead, or send a member of the imperial family to lead, a Greek regiment fighting alongside the Turks whenever the sultan set out on an expedition.

The Ottomans continued to win one battle after another, seemingly impervious to defeat. In 1385 they took the Bulgarian capital of Sofia. In 1387 the Macedonian capital of Thessaloniki also fell into their hands. The subjugation of the Byzantines progressed so far that when infighting among the imperial family made it impossible to decide the next successor to the throne, they would await the decision of the Ottoman sultan who, in his own time, would dispense his sanction. Thus by the end of the fourteenth century, all that remained of the Byzantine Empire was Constantinople, its environs, and the inland portion of the Peloponnesian peninsula. It was around this time that the emperor went to Western Europe begging for reinforcements to hold back the Ottomans. Anybody who knew the reality of the eastern Mediterranean of the time could see that the Byzantine Empire was clearly on the brink of collapse. To assert that the Ottoman encirclement of Constantinople was not complete would have been impossible even for an optimist.

Rushing home upon hearing that the Turks were advancing on Constantinople, Emperor Manuel learned instead that the Ottoman threat had vanished in the course of one morning. In that year, 1402, Ottoman forces led by Sultan Beyazid suffered a complete defeat in Ankara at the hands of a Mongol army led by Timur. The sultan himself was taken captive. Hunted down by the Mongol forces, the great Ottoman army had vanished without a trace. Although the Turkish soldiers were famed for their cruelty, the Mongolian forces were even more vicious: it was said that where the Mongol army had passed, one could hear neither the barking of dogs, nor the singing of birds, nor the crying of children.

Having tasted its first defeat and with its sultan in the hands of the enemy, the Ottoman court immediately splintered into factions. This infighting continued beyond the death of Timur three years later and the rapid collapse of the Mongol Empire that attended it. All of the Ottomans’ vassal states, from the Byzantine Empire down, saw this as a good opportunity to regain their independence. During the twenty years that it took the Turks to recover from their defeat by the Mongols, these states shrugged off their tributary payments and refused to send troops, but they did nothing to enhance their own capacity for self-defense. Indeed, when the Turks went on the offensive once again after those twenty years, the former vassal states could do nothing to stop them. Constantinople was again surrounded, the Byzantine Empire and the other vassal states conceded to Sultan Murad’s demands, and the twenty-year hiatus of tribute payments and troop offerings came to an end. It was back to 1402.

But Murad, believing perhaps that simply maintaining the lands under his control was the best policy, did not launch any large-scale acts of aggression for the next thirty years. Battles were fought, mainly of a defensive nature, but they did not occur close to Constantinople. The city at that time, despite being the nominal capital of the Byzantine Empire, was rather in the position of a free port city. The commercial city-states of the West, Genoa and Venice, as well as the trading peoples of the Orient—the Arabs, Armenians, and Jews—all used the city as the base from which to compete economically with one another. The Turks, unlike their coreligionists the Arabs, were essentially a nomadic people and unskilled in the art of commerce. Perhaps for this reason they were willing to give tacit consent to the existence of a simple free port city, the activities of which enriched their capital of Adrianople as well. It was well known that Murad’s most trusted vizier, Halil Pasha, was sympathetic to the West and to the Byzantines. Venice and Genoa had publicly signed friendship and trading agreements with the Ottomans, and both sides had secured considerable profit from trade via Constantinople with cities in Asia and on the Black Sea coast. The Ottomans’ policy of rule during the first half of the fifteenth century was a pragmatic recognition of compromise as a means toward mutual benefit. That compromise was allowing the Byzantine Empire, which had been reduced to only Constantinople, to continue to exist.

What the powers of the West and the Byzantine Empire didn’t know, however, was that a young man with an extraordinary interest in Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar was coming of age in the plains of Asia Minor.

Mehmed the Second, the third son of Sultan Murad, was born in the Ottoman capital of Adrianople in 1432. His mother was low born, a slave who had been forced to convert from Christianity to Islam. Sultan Murad, perhaps because he felt no special favor towards Mehmed’s mother, sent the boy, his mother, and his wet-nurse to the Anatolian city of Amasya when the boy was two. Amasya was then governed by Murad’s eldest son, who died three years later. The governor’s post was not considered to be anything particularly important, and so was handed down to five-year-old Mehmed. As the sultan’s son, Mehmed was also occasionally invited to banquets given at the capital in Adrianople. After a short time, Mehmed’s remaining older brother was given the Amasya governorship while he was put in charge of Manisa.

In 1443, however, his older brother was killed by an unknown assassin. Eleven-year-old Mehmed was now the only heir to the throne, which prompted his father Murad, who had never given Mehmed any particular attention up until this point, to summon him to the capital. Separated from his mother and still only a child, Mehmed had to serve as the regent while his father was away fighting in various campaigns.

Mehmed’s advisor during these times was Halil Pasha. More than an advisor, he was in fact Mehmed’s overseer. When he disagreed with the young ruler’s words or actions, he not only protested in a loud and commanding manner, but also often forced Mehmed to retract his previous statements. Unlike most of the other ministers, who were former slaves and converts from Christianity, Halil alone was the son of a former vizier and a pure-blooded Turk. Yet his high birth was not the only reason he was able to do as he pleased: Sultan Murad had absolute confidence in Halil’s political acumen and sense of balance. He instructed his son to call Halil Pasha (who was in fact officially Mehmed’s servant) by the honorific term lala, or “tutor.”

The next year, however, Sultan Murad suddenly abdicated the throne. He had just dealt a severe blow to the Christian armies at Varna and perhaps felt that Turkish territories were now secure. Not only the Turks, but the peoples of Europe as well, couldn’t but be startled that Murad, still in his prime at forty years old, should retire so early. His viziers implored him to change his mind, but Murad held firm in his decision. He handed over his throne to his twelve-year-old son and quickly retired to Manisa. For some time after that, though, the espionage organs of Venice, unwilling to believe that a complete transfer of power had occurred, referred to Mehmed in Adrianople as the “Sultan of Europe” and Murat in Anatolian Manisa as the “Sultan of Asia.”

In fact, Mehmed’s hold on power was short-lived, as his father returned after less than two years to retake the throne as suddenly as he had abdicated it. The instigator of this coup d’état of sorts was none other than Halil Pasha, who is said either to have been alarmed by the fourteen-year-old Mehmed’s germinating designs on Constantinople or to have been desperate over the fact that Mehmed hadn’t won the confidence of the elite Janissary troops. Although Halil Pasha was the one who asked Murad to return, two other ministers, Ishak Pasha and Saruja Pasha, also concurred with the decision. Mehmet, unaware of these machinations, was sent out hunting on the day his father returned to the capital; by the time he arrived back at the palace, it was too late for him to do anything.

Murad ordered Mehmed to be confined to his quarters at the palace in Manisa. Sending him to the same city where he himself had passed his short-lived retirement was tantamount to exile. Murad once again took the helm and proclaimed that his three viziers, Halil, Ishak, and Saruja, would remain at their posts. Among the viziers, only Zaganos Pasha was demoted and sent to Asia along with Mehmed, for dereliction of duty.

Mehmed’s honor was shattered by this humiliation, as might be expected, since he was already fourteen, an age when it was not unusual for a man to be treated as an adult, and since he had a naturally very proud character. No doubt he passed his days at Manisa in a very different frame of mind than he had at the palace in Adrianople. His father occasionally allowed Mehmed to join him on military campaigns, but nothing about Mehmed’s performance on these occasions was considered particularly noteworthy. Given the fact that Mehmed would later display a most remarkable strategic and tactical prowess, the only possible reason for this is that his father the sultan didn’t allow him near the theater of combat. Mehmed was much better known at the time for his sexual exploits with both genders in far-away Manisa than he was for his skills as a warrior.

In the second year of his exile, Mehmed fathered a son, Beyazid. The mother was an Albanian, a former Christian slave much like Mehmed’s own mother. A year later he took as his official wife a young woman from a Turkish family that was prominent enough that her older sister had been given to the sultan of Cairo. This new bride was considered to surpass her sister in beauty, yet it appears that her sixteen-year-old husband did not even bother to make love to her. They had no children. At around the same time, Mehmed’s mother passed away.

In February 1451, the fifth year of his exile, Mehmed learned of his father’s death. Murad, who was a heavy drinker despite Islam’s injunctions against alcohol, suddenly collapsed one day and never regained consciousness. Three days later he was dead, at the age of 47. Grand Vizier Halil followed the protocol for such occasions and did not immediately announce the sultan’s death, instead sending a messenger to Manisa. Mehmed received the news three days after the fact.

The young man, two months shy of his nineteenth birthday, didn’t wait for the formal preparations for a new sultan’s entry into the capital to be properly completed.

“Those who are with me, come!” was all he said. He mounted his beloved Arabian stallion and galloped northward. He knew full well what the viziers and Janissaries had thought of him until that point. Furthermore, he knew that he had an infant half-brother whose mother, born of an elite Turkish family, had been one of Murad’s favorites. He drove his horse through the day and the night, only stopping to rest while aboard the boat crossing the Dardanelles.

On February 18, 1451, Mehmed the Second formally acceded to the throne. The leading citizens of Turkish society crowded into the Great Hall of the palace, but nobody, with the exception of the Chief Eunuch of the Harem, was allowed near the young sultan’s throne. Even the Grand Vizier Halil Pasha and the viziers Ishak Pasha and Saruja Pasha, were standing quite some distance away. Everybody in the hall that day knew why, and the atmosphere in the room was very tense.

“Why are my ministers so far away?” Mehmed asked, for all to hear. Then he turned to the Chief Eunuch. “Tell Halil Pasha he should return to his seat.”

At that moment the heaviness in the air lifted. With this it was decided that Halil Pasha and all of the viziers beneath him would be allowed to retain their posts. Mehmed the Second turned then to the three men who had in the meantime lined up to the right of his throne, and continued:

“Ishak Pasha, I would like you, as the head of the Anatolian Corps, to accompany my father’s body to the cemetery in Bursa.” Ishak Pasha stepped forward to the throne and knelt down so that his forehead touched the ground in the customary Turkish sign of respect. The former sultan’s favored mistress then stepped forward to offer her felicitations on the occasion of the new sultan’s accession to the throne. Mehmed the Second graciously accepted his stepmother’s congratulations and then offered her to Ishak Pasha as a wife, thereby saving her from an uncertain future. While this spectacle was unfolding in the Great Hall, however, an infant was being drowned in a tub in the Harem baths. With this, Mehmed the Second established the Ottoman custom of murdering one’s siblings upon taking the throne.

Halil Pasha could have just as easily been beheaded, but things were not as simple as believed by those who breathed a sigh of relief at his retention as Grand Vizier. It was well known that Ishak Pasha was Halil Pasha’s sworn friend and had been sympathetic to the plot to reinstate Murad on the throne. After Ishak buried the former sultan he was relegated to Anatolia and not allowed to return to the capital. Mehmed had shrewdly cut Halil off from one of his closest friends and supporters, and replaced him with Zaganos Pasha, the vizier whom the former sultan had demoted.

Neither the Byzantine Empire nor the powers of the West thought very deeply about the meaning of this chain of events. This was because the new sultan had renewed his father’s non-aggression pact with the Byzantine Empire and its less prominent neighbors without presenting any difficult obstacles. The renewal of the trade and friendship agreements with Genoa and Venice had also been completely trouble-free. The young sultan also repatriated the King of Serbia’s younger sister, Mara, who had been offered to Sultan Murad’s harem and was in fact one of his official wives, but who had failed to bear him any children. He not only returned her dowry money but even gave her numerous presents and an allowance for traveling expenses. Since it was well known even in the West that Mara had maintained her Christian faith throughout her stay in the harem, there were many there who took this as proof of the new sultan’s moderate attitude towards Christians. The countries of Europe judged the new, nineteen-year-old sultan to be a vessel consecrated only to the continuation of his father’s legacy of greatness in battle and noble-minded justice.

There were a few people, very few, who couldn’t take such an optimistic view. One of them was the Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI. Regardless of the fact that the Turks and Byzantines had renewed their mutual non-aggression treaty, less than a month after Mehmed the Second’s enthronement he sent an envoy to Western Europe requesting military reinforcements. Yet, any such request would immediately become tied up with the problem of reunifying the Greek Orthodox and Catholic Churches, and even the Emperor himself knew not to expect a simple resolution.