Culloden was the last pitched battle fought on British soil. The conflict between Scotland and England had ended. The Highlanders who had followed the Catholic Prince Charlie gradually converted to Protestantism (except for Barra, Benbecula and South Uist, which retain a Catholic majority to this day). In the nineteenth century, Victoria was to take the throne.

Peace had come, except that during Victoria’s reign were the First and Second Afghan Wars, the China Wars, the First and Second Sikh Wars, the Maori Wars, the Cape Frontier Wars, the Crimean War, the Ashanti Wars, the Zulu War, the Transvaal Rebellion, the Egypt and the Sudan Wars and the Boer War. Many Scottish soldiers, officers and men fought solidly for the British Empire.

The nineteenth century was an age of industrial revolution, an age of prosperity and an age of workhouses and cholera.

![]()

The last ‘total war’, the Napoleonic War, ended in 1815. It would be ninety-nine years before European powers would again face each other on European soil.

Hume Castle is an unusual-looking medieval Scottish castle because most of the stones and mortar to be seen are a folly created towards the end of the eighteenth century. However, the castle does have a long history dating back to the thirteenth century at least, and has a long association with the Home Clan.

The family are variously known as Home, or Hume, or Home pronounced Hume, and the clan is often referred to as Home/Hume. There is a story that whilst leading his men into the Battle of Flodden, Sir Alexander Home shouted out his family battle cry ‘A Home, A Home’, at which some of the troops turned tail, thinking he had ordered a retreat. This led to the change in pronunciation. The story is not verified on the Clan Home website.

The confusion in name continues with two more recent family sons: Sir Alex Douglas-Home (pronounced Hume) was British Prime Minister in the 1960s; Allan Octavian Hume was one of the founding spirits of the Indian National Congress (which eventually led India out of British rule) and in 1885 served as its first secretary.

Standing within sight of the English border, Castle Hume has been no stranger to conflict as campaigns proceeded north and south. It has at various times been in English hands for prolonged periods. Perhaps the greatest damage occurred in 1651 when Cromwell’s troops, having achieved the surrender of the castle, chose to destroy it with explosives rather than hold it.

The 3rd Lord Marchmont, a Home, bought it in 1770 and created the structure we see today. One of its great stories, not to say embarrassments, was still to come. In 1804 the country was poised ready for invasions by Napoleon’s forces. The technology to signal the arrival of the attack was ancient and well tried – beacon fires. The fires were stationed along the coast, each in sight of the previous one and the next. A lit beacon would send the signal racing up the coast.

On the night of 31 January 1804 a sergeant in the Berwickshire Volunteers saw the vital flames light up and ordered his beacon at Hume Castle to be lit. The signal went and 3,000 volunteers poured into the night ready to fend off Boney’s invasion.

What, it turned out, the sergeant had seen were the fires from charcoal burners on the Cheviot Hills. There was no fleet and no invasion. The incident was christened ‘the Great Alarm’.

![]()

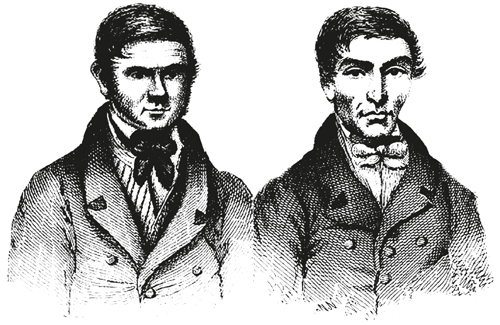

William Burke was from County Donegal in Ireland, and William Hare was probably from County Down. Both men came to Scotland seeking labouring work. Both worked as navvies digging the canal system, but they didn’t meet until the start of 1828. In the course of that single year their activities made them famous as ‘Burke and Hare, Body Snatchers!’

There was a great demand for dead bodies for research and teaching student surgeons. The legal supply was limited so it was supplemented by illegal means. Gangs would enter graveyards in the dead of night and remove freshly buried corpses from their graves. This led to a variety of preventative measures such as guards in graveyards or Mort Safes (these were metal cages locked over graves long enough for the body to have rotted until it was no longer an attractive proposition to recover, usually about six weeks).

Burke and Hare came to supply the hospitals’ demand, but they did not dig up a single corpse. They found a novel way to find ‘subjects’ – murder. Their first corpse, Old Donald, died of natural causes. Hare and his wife Margaret, or Maggie, ran a boarding house in the West Bow of Edinburgh’s Grassmarket. William Burke came to stay as a lodger. An elderly lodger passed away owing considerable back rent (he had been due to pick up his annual army pension, but now this would not be forthcoming). Hare had already ordered the coffin to take him away, so it is likely that it was Burke who suggested selling his body to recover the rent.

The two men went to Edinburgh’s Surgeon’s Square where they met eminent surgeon Dr Robert Knox and several students, one of whom was William Ferguson, later to be Sir William Ferguson, Queen Victoria’s doctor. The matter was discussed and the corpse duly delivered. A price of £7 10s was paid. It was a fortune for the two men.

Their next opportunity came when a second lodger, Joseph, became ill. He had the fever and Hare’s wife was naturally anxious to get him out of the house. Burke and Hare somehow agreed that a spot of euthanasia was called for. They smothered the old man with a pillow and got their second fee from the good doctor. This launched a spree which would see at least sixteen people murdered by the end of the year.

They quickly developed an effective modus operandi. They would lure people into the lodging house and entertain them with copious amounts of whisky. When they had passed out, or were sufficiently insensible, they would smother them. One of them would use one hand to close the mouth and nose, while the other held the victim’s legs to stop them struggling. The bodies were then carted off in barrels to the surgeon. It was a profitable enterprise, but after a while they started getting rash. Towards the end some have said that they looked as if they wanted to be caught. Certainly Burke was so haunted by visions of their work that he couldn’t sleep without a candle burning with a bottle of whisky inside him and another by his bed.

Burke, on one occasion, came across a police constable taking a drunken woman to the station. Burke, by all accounts a charmer, persuaded the policeman that he would save him trouble and would himself take care of the lady. He did indeed ‘take care of her’.

The murder of Mary Patterson turned into a fiasco. Burke turned up with two young ladies. After one of them left, Burke’s common-law wife Helen MacDougal attacked him for flirting with this very pretty girl. MacDougal left and Hare arrived. Mary was dispatched in the usual manner. The other girl, Janet Brown, turned up looking for her friend. Burke concocted a story that she had met a packman and decided to go to Glasgow with him. MacDougal reappeared, still in a jealous rage. An argument ensued while Mary Patterson was lying dead just a few feet away in the next room.

Things got no better when they got the body to the doctor’s. Knox was so taken with the pretty corpse that he sent for an artist who drew the corpse in the pose of Venus. The problem for Burke and Hare was that they had previously drawn victims from the lower classes. Mary was low class but her profession allowed her to meet and deal with men of a higher class. She was a prostitute. In Surgeon’s Square she was immediately recognised by at least two of the students. It is likely that they were former clients of the dead girl. One said that he had seen a girl standing in the Grassmarket and that she and this girl were ‘as like as two peas in a pod’. Burke explained that she had died of drink and had been sold to them by an old woman. The young doctors did nothing to pursue the matter.

James Wilson was a big mistake too. Known as Daft Jamie, he was a ‘simpleton’ who was a well-known character in the area. Killing him had been a struggle since he refused drink and was a strong lad. At the doctor’s he was recognised straight away, but Knox denied this, quickly removing Jamie’s head and distinctive club foot.

Their next murder, Mary Docherty, was their final error. Mr and Mrs Grey, lodgers in the guest house, became suspicious and went to the police. Burke, Hare, Margaret and Helen were arrested.

The authorities quickly recognised that they had a problem: lack of evidence. They only had one body, the last. The others had been skilfully and meticulously dismembered by the surgeons. The one that they did have showed no signs of assault (the smothering technique left the bodies without a mark, always a good selling point). The doctors would not admit that there was any evidence of foul play.

The public were baying for blood and yet Burke and Hare might walk free. Something had to be done. Sir William Rae, the Lord Advocate, approached Hare and asked him to turn King’s Evidence – he could incriminate Burke and walk away. Hare grabbed at the chance.

Curiously, Hare’s account, the account which saw Burke swing on the gallows, went missing and there is no record of his statement. Burke, on the other hand, sang like a canary. He gave a full confession and an extended interview to the Edinburgh newspaper the Courant. These can readily be accessed. What we know of the pair’s exploits is from Burke’s point of view. Hare’s story is not known.

A strong reason for Burke’s openness was his plea that his love, Helen MacDougal, had never been involved. MacDougal got off with the unique Scottish verdict of ‘not proven’ (which some have defined as ‘Innocent, but don’t do it again!’). Burke was convicted and sentenced. A crowd of 25,000 turned out in the Grassmarket to see him hang. This same mob was furious that Margaret and William Hare were to be freed. Daft Jamie’s family tried to launch a private prosecution. Hare was smuggled out of Edinburgh.

When the coach stopped at a coaching inn in Lamancha in the Borders, Hare was recognised. Word went ahead and there was a mob 9,000-strong waiting for him in Dumfries. Again he was smuggled away. His consequent movements are a matter of speculation.

Burke entered the language as the word ‘burker’ for body snatchers or gravediggers with ‘burking’ as their activity. Of course we know that Burke and Hare had no part in such goings on – they were merely murderers.

In the activities of Burke and Hare the medical staff were complicit. They never asked questions as to the origins of the corpses and even when there were clear indications that something was awry, for example with Mary Patterson or Daft Jamie, they took no action. While they suffered a certain amount of public displeasure, no charges were ever brought against them.

A doctor in Aberdeen was paid back for dealing in illegal corpses in a more direct fashion. The lovely story was published in the Fife Journal in 1829, when the deeds of Burke and Hare were fresh in the public mind.

It seems that an English ship returning from America berthed in Aberdeen. After the long sea crossing, the crew partook of some strong drink. When the conversation turned to the body trade and particularly the lack of justice for the doctors, a plan was hatched:

A daring man of colour volunteered to be the subject, provided they could furnish him with a large knife. Being equipped with one of a proper size, he was put into a sack which had been procured; and three of the crew of the best address, called at the house of a Lecturer on Anatomy and disposed of the body, telling him it was one of their messmates who, previous to their arrival, had died of apoplexy. Having got £3 in hand, with the promise of more next day, they carried the corpse down into the cellar, the lecturer and his servant coming along with them and locking the door.

The African cut his way out of the sack and was waiting for the doctor. When the attack came the doctor fled, pursued by the corpse he had come down to examine. No matter how much a man of science and reason he may have been, we cannot help but wonder how much the legends of Black Nick, the Devil himself, rang through the man’s mind.

The sailor returned to his companions and ‘the whole crew, gloriously fu’, returned to their vessel, which sailed next morning.

An activity as bizarre as grave digging inspires many stories. The grave diggers were also known as resurrection men or resurrectionists. In one case, at least, the term came close to the truth.

In the village of Chirnside in the Borders, a young minister moved to the parish with his young wife. Shortly afterwards he was devastated when his love took ill and died. Her funeral took place and she was buried in the local graveyard. A pretty young corpse was likely to fetch a good price. The temptation was too great and a party of resurrectionists turned up that night.

In the course of the exhumation one of the party noticed a ring on her finger. When he couldn’t remove the ring he took his knife and sliced off the finger. The girl’s eyes opened and stared at him. The shock had been enough to rouse her from her catatonic state. The rogues fled at some speed. The young woman made her way back to the manse. She appeared at the door in a shroud covered in blood: her husband fainted on the spot. The story, of course, goes on to tell that she lived a happy life, albeit minus a finger.

We have to admit that there is scope in this tale for the blurring of fact and fiction. The story is genuinely part of the local traditions of Chirnside. We heard it told by primary school children in the village. They learned it from a senior teacher who was born and bred in the area. There are many examples of local traditions turning out to be more accurate than versions written by partisan historians.

We were somewhat surprised to come across another story from Chirnside, this time set in the seventeenth century, well before the era of the bodysnatcher. In this a young woman is buried and comes back to life when someone tries to sever her finger. In this instance the culprit is a villainous sexton bent on robbing her of her jewellery. It seems unlikely that there were two such incidents, more likely that one story received an update a couple of centuries later.

In Victorian times there was a great deal of concern about the possibility of being buried alive. Some people with a morbid fear would erect elaborate structures which would allow the awakening corpse to pull a string and ring a bell above ground. There is no doubt that it did happen. In fact it happened to one of Scotland’s most brilliant philosophers.

Curiously, given the Chirnside incident, a man from nearby Duns in Berwickshire also had a catatonic incident, but with a less happy result. It was six centuries earlier. John Duns Scotus took his name from where he was born in the 1260s. He came to be regarded as one of the most important philosopher/theologians in medieval Europe. He has the distinction of adding a word to the language: his followers, known for their intransigence, were called ‘Dunses’ which has come down to us as ‘dunces’.

John Scotus, despite his genius, turned out to be not too bright about letting people know of his medical problems. On orders from the Franciscan Minister General, he travelled at short notice to Cologne in 1308. His servant was to follow. John took ill and, apparently, died. He was laid in a coffin and placed in a vault. His servant, who had been unavoidably delayed, was horrified and cried that they had probably buried his master alive.

The servant was aware that John suffered from fits which left him in a coma, a death-like state. He would recover after a time. The servant knew, but no one in Cologne did. When the coffin was opened they did indeed find his hands torn, his fingers shredded in a desperate attempt to get out of his tomb.

The story was recorded in Francis Bacon’s Historia Vitae et Mortis. A Latin inscription on Duns Scotus’s tomb is translated as follows:

Mark this man’s demise, O traveler,

For here lies John Scot, once interr’d

But twice dead; we are now wiser

And still alive, who then so err’d.

![]()

For the science of anatomy to proceed at all there had to be some legal way of obtaining corpses. There was: the bodies of hanged criminals.

In 1818, curiously the same year that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was published, there were two exhibitions for the entertainment of the public in Glasgow.

The first was in Jail Square at the foot of the Saltmarket. Matthew Clydesdale, a weaver from Airdrie, was convicted for the murder of a 70-year-old man. He was sentenced to be hanged and dissected.

On 1 September he was brought to the Square. Also on the scaffold was a young thief called Simon Ross. It was the first execution in Glasgow for some time and a big crowd turned out to watch. Soldiers were deployed to keep the crowd under control. There was also a rumour that a team of Lanarkshire miners were on the way to rescue Clydesdale. They didn’t materialise.

When the convicts were pronounced dead, Clydesdale was let down and placed in a cart, in which he was transported up the Saltmarket, across the Trongate and up the High Street to Glasgow University.

For the second time that day Matthew was on public display, this time for his dissection. The anatomy theatre was packed. The anatomists were Dr Andrew Ure, senior lecturer at the recently founded Anderson’s Institution and Professor James Jeffray, Professor of Anatomy, Botany & Midwifery at Glasgow University.

The story of the events did not get much attention at the time but Peter Mackenzie, a writer and ‘character’ of Glasgow who claimed to have been present, recounted the events in his three-volume Reminiscences of Glasgow and the West of Scotland in the 1860s. The proceedings had commenced when Clydesdale suddenly burst to life, shocking the entire audience. The response of the anatomist was to grab a scalpel and slit the poor man’s throat, killing him for the second time that day. So much for the belief that you can’t be executed twice for the same crime.

MacKenzie’s account was dramatic but not entirely accurate. The reality, however, was even more bizarre – the anatomists quite deliberately intended to bring Clydesdale back to life (up to a point).

In the 1980s Dr Fred Pattison, whose ancestor Granville Sharp Pattison was an anatomist who was tried for bodysnatching, unearthed Dr Ure’s account:

This event, however little desirable with a murderer, and perhaps contrary to the law, would yet have been pardonable in one instance, as it would have been highly honourable and useful to science.

The science behind the experiment was ‘galvanisation’, the use of electric stimulation. Preliminary dissection had exposed various sites on the man’s body. Rods attached to a galvanic battery charged with dilute nitric and sulphuric acids were attached to Clydesdale’s nervous system. The first attachment to the heel and spinal cord induced a violent kick which nearly knocked an assistant over. This might have been impressive enough, but we can only imagine the awed hush from the audience at the next step ... Clydesdale started breathing. The rods had been attached to the phrenic nerve and diaphragm. As Ure himself put it:

The success of it was truly wonderful. Full, nay, laborious breathing instantly commenced. The chest heaved and fell; the belly was protruded and again collapsed, with the retiring and collapsing diaphragm.

Perhaps the most dramatic events occurred when the current was applied to the supraorbital nerve and heel. By varying the voltage:

... most horrible grimaces were exhibited ... Rage, horror, despair, anguish and ghastly smiles united their hideous expression in the murderer’s face. At this period several spectators were forced to leave the apartment from terror or sickness, and one gentleman fainted.

The show was astounding but at no time did Clydesdale actually come to life, nor had the anatomists any expectation that he would. Fred Pattison does draw attention to a note of Ure’s that passing current through brass knobs placed on the skin over the phrenic nerve might be effective in restoring life. He was close to describing a defibrillator.

![]()

Although it lost its currency and measurements, Scotland did maintain its own separate legal system, based around the Sheriff Courts. The Glasgow sheriff was challenged by this case in the mid-nineteenth century.

Peter Mackenzie’s Reminiscences of Glasgow and the West of Scotland proves to be a treasure house of strange but true stories. We know from the Clydesdale case that his accuracy in reporting may be flawed, but felt it worth relaying this story.

The Shanks family were living in one of the mansions in St Andrew’s Square, Glasgow, having recently returned from the West Indies. They had a well-loved pet canary. The bird made a bid for freedom, flying through an open window. It alighted, in the first instance, on the steps of St Andrew’s church.

In Mackenzie’s words, ‘This pretty, fluttering, innocent Canary bird, was soon seen and chased and caught on the steps of St. Andrew’s Church, by a poor little beggar boy, soliciting alms in the neighbourhood, who treated it most kindly; he pressed it into the bosom of his tattered shirt …’

The boy’s action was observed by a Mr Pinkerton, a prominent wine merchant. Since the boy would have no way of keeping the bird in the comfort it was used to, Pinkerton offered the boy 1s 6d for it. It was a good day’s income for the boy and he was happy to accept. Pinkerton took the bird home, provided a cage and all the necessary accoutrements. His family called it Dicky.

The Shanks family were distressed at the loss of their pet. They had handbills printed offering a reward for the safe return of the bird.

Despite his family’s attachment to Dicky, Pinkerton did the honourable thing and reported his story to the Shanks. He offered to return the bird, with the small proviso that his outlay of 1s 6d be repaid, a paltry sum to this class of people.

The Shanks did not see it that way; instead they threatened him ‘that if he did not beg their pardon, and immediately restore the bird to them, they would punish him with the action of the Law’. Pinkerton was provoked by this and demanded that they prove that this was indeed their canary.

And here a thumping law plea began, which ultimately cost some hundreds of pounds but which might have been settled at the outset for one shilling and sixpence on the head of the poor Canary; and yet that Canary deserves to be immortalised, for the wonderful results it produced in all the Courts of this kingdom of Scotland ...

The Shanks employed Mr Michael Gilfillan, a prominent lawyer who argued in a ten- or twelve-page document that Mr Pinkerton ‘had stolen, or fraudulently obtained possession of their bird’.

Pinkerton employed Mr Alex Ure who contended that Pinkerton ‘became the bona fide purchaser of it, in broad day-light, on the public streets of Glasgow…’.

The arguments raged on. The sheriff, a Mr Hamilton, eventually judged against Pinkerton and ordered the return of the bird. But the bird was dead, the victim of a stray cat: ‘Mr. Ure, recapitulating the fact that the bird had been slain, and the cat itself hanged for the foul deed.’

So it was back to court again. The court was increasingly upset that so much of its time was being wasted over the trifling matter of 1s 6d. Mackenzie contends that it was a case that ultimately led to a change in the law in Scotland: the setting up of the Small Claims court.

In 1828 Mary Mackintosh was put up for sale in the Grassmarket in Edinburgh. She had a straw rope tied around her middle and the words ‘To be sold by public auction’ around her neck. The proceedings were recorded in great detail by a broadside (broadsides were publications containing news, sold on the streets).

The event drew a big crowd. A Highland drover opened the bidding at 10 and 20s (£1.50). A tinker shouted that she should not be taken to the Highlands and upped the price by 6d. A Killarney ‘pig jobber’ raised by 2s. A brogue maker wonderfully described as being ‘as drunk as fifty cats in a wallet’ took exception and laid the Killarney man out before attacking the auctioneer.

A monstrous regiment of women, supposedly 700 strong, appeared, incensed by the entire proceeding. They attacked the crowd armed with stones in stockings. The auctioneer and the husband of the woman for sale were beaten as the whole scene turned into a general battle, with only the arrival of the police stopping lives being lost.

After the disturbance had been quelled bidding resumed and the lady was sold to a widowed farmer for the price of £2 5s.

Jack Renton from Stromness followed many of his fellow Orcadians to sea. Like many, he returned with tales to tell. Jack’s story was exciting enough – Shanghaied, captured by ‘savages’, escaping on a slave ship – but it has only recently emerged that he didn’t tell the whole truth. The untold part of the adventure lived on in an oral tradition 9,000 miles away from Orkney.

In 1568 the Spanish found a group of islands east of Papua New Guinea; they named them the Solomon Islands, since such a remote and lush place would surely contain treasures equal to that of the biblical king. The islands would become a British protectorate in 1898. In the intervening years they were pretty much avoided – with good reason! The islands were populated by tribes constantly warring with each other and with any visitors from outside. The Solomons gained a reputation as a dangerous place teeming with headhunters and cannibals.

It was in 1868 that Jack Renton found himself there. He had been Shanghaied in San Francisco along with four other men. The ship was a tub called the Reynard which was bound for McKean’s island in the Pacific. The cargo she was shipping was guano, bird poo. We can only imagine how bad the conditions must have been on board for the five men to believe that casting themselves adrift in an open boat in the vast Pacific ocean was a better option.

The venture was as foolhardy as it sounds. Drifting for forty days, three of the men perished. The remaining two were in pretty poor shape when they ran aground on the island of Malaita, on the dangerous coast of the Solomons. The locals, turning out a welcoming party, lived up to their billing and promptly clubbed one of the men to death. For Jack Renton fate intervened in the arrival of an armed party from a rival tribe. Jack was snatched and taken to the small offshore island of Sulufou.

There he was kept as a curiosity. Jack managed to charm the local chieftain who later adopted him as a son. With the chief’s protection he survived. He learned the language and tried to teach the islanders better fishing and farming techniques. For eight years he lived in what he later described as the ‘most savage place on earth’.

Jack’s position was not entirely unknown. Rumours circulated that a white man was living amongst the natives on the island. A Captain MacFarlane visited on a ship called Rose and Thistle and tried to barter for the white man’s release. He came away empty-handed.

Three years later, in 1875, a slave trading ship, the Bobtailed Nag, anchored off the island. Jack persuaded the islanders to let him send a message to the ship. He wrote on a piece of driftwood with charcoal, ‘John Renton. Please take me off to England.’ The captain, a Scot named Murray, had heard rumours further down the coast, and was willing to help. Thomas Slade, one of the crew, reported that when it was clear that Jack was leaving there was ‘great lamentation and real tears’ from the islanders. Jack left the island with a promise that he would return with goods that would help the tribe, and returned to a hero’s welcome.

That much of the story he freely told; Jack himself published his account in the Brisbane Courier and The Adventures of Jack Renton in 1875, but on the Solomon Islands he was not forgotten. Mike McCoy, an Australian biologist, lived among the modern islanders for twenty-six years. He discovered that the history of the Malaition people retained in the oral tradition by the tribal storytellers featured a white man. The man, Jack Renton, had indeed been on the island, he had indeed assimilated into the tribal culture and that did indeed include participation in the warfare against neighbouring clans. As Mike McCoy puts it:

There is no doubt that Renton became a headhunter. He would have had to for his street credibility. The islanders recall even now what a strong warrior he was. Renton was accepted into male society and lived in the men’s long house. He apparently killed several people from inland and took heads. His warrior prowess and closeness to the salt-water people chief, Kabou, led to the bush people putting a bounty on his head. When he went to his favourite spots – one was an idyllic-looking natural swimming pool on the main island - he always had an armed guard to protect him.

These revelations make sense of the objects Jack brought home with him, a spear and a necklace of sixty-four human teeth, which are now in the National Museum of Scotland.

Jack, like Mungo Park before him, could not settle back in Scotland and did return as promised to the island, bringing tools and supplies. His knowledge of the culture and language led to him being recruited by the Queensland government to explore the area and control the activities of the slave traders.

In 1878 Jack, en route to Australia, went ashore on the New Hebrides with a companion to collect water. When he didn’t return to the ship a search party went ashore and returned with two bodies. Two bodies, but neither was complete. The ‘Great White Head Hunter’ had lost his head.

![]()

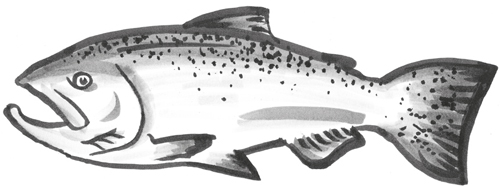

It is widely known among fishermen, or should that be fisherpersons, that women are better at catching salmon than men. This is epitomised by the fact that the biggest salmon ever caught on rod and line in the British Isles was caught by Georgina Ballantine on the Glendelvine beat of the River Tay. At 64lb (29.02988kg for our younger readers), 54in long (1.3766m), it has never been beaten, nor is it ever likely to be.

Georgina is not the only lady who has beaten the men to the biggest fish: Clementina Morrison caught a 61lb salmon from the River Deveron in October 1924; Doreen Davey caught a 59½lb salmon in March 1923 from the Wye; Gladys Blanche Huntington caught a 55lb salmon from the River Awe; and Lettice Ward caught a 50lb fish from the Kinnaird beat of the Tay.

Georgina Ballantine’s fish tops them all. On 7 October 1922 Georgina got a message that the laird would not be fishing on that day and that she had the opportunity to fish. ‘A whole day’s fishing on a glorious sunny autumn day, how I rejoiced to be alive!’ she wrote in a letter recently shared by Scottish writer Bruce Sandison. In the letter she notes, ‘One thing is certain, that a good deal of the angler’s success – or failure – depends on the efficiency of the man on the oars. The oarsman that day was one of the finest anglers who ever cast a salmon fly on the waters of the mighty Tay – my father.’

During the course of the day she caught three fish, totalling 63lb. A good day’s fishing by any standards, but then at 6.15 p.m. she hooked a fourth fish and, in her own words, after ‘two hours and five minutes of nerve-wracking anxiety, thrilling excitement and good stiff work’ she and her father boated the largest salmon ever caught in the British Isles.

Sandison tells:

When a cast of Georgina’s salmon was displayed in the window of PD Malloch’s shop in Perth, she stood at the back of the crowd who had gathered to admire it. Two elderly men were particularly overawed by the size of the salmon and Georgina heard them talking: one said to the other, ‘A woman? Nae woman ever took a fish like that oot of the water, mon. I would need a horse, a block and tackle, tae tak a fish like that oot. A woman – that’s a lee anyway.’

The cast is now in Perth Museum.

According to Professor Peter Behan of Glasgow University, a neurologist, the reason women are better at catching salmon is down to sex. Most of the monster salmon are male, and human female scent is more attractive to them (a strong sense of smell is widely believed to be at least part of the reason that salmon can find their way back to the river of their birth).

Observations made through an observation window in a fish ladder suggested that if a man put a finger in the water upstream the fish would become agitated and would hang back for half an hour, while if a woman put her whole hand in the water the fish would be unperturbed. In his book Salmon and Women – the Feminine Angle written with Wilma Patterson, Professor Behan puts this phenomenon down to pheromones – sex hormones. This theory has led to men tying flies with their wife’s pubic hair.

In his 2012 book Glorious Gentlemen, Sandison asked the question of a number of Scotland’s top ghillies (angling guides). Their answer was that women do make the best salmon anglers, but because they are more patient, more willing to listen to advice and less inclined to engage in the macho aim of casting to the far bank no matter where the fish are, rather than it being down to biochemistry.

![]()

In 1862 Jennie Quigley left Glasgow for America. She was 13 years old and was under 2ft tall (she did eventually reach 41in). She was taken on by P.T. Barnum, named the ‘Scottish Queen’ and was billed the smallest woman in the world. As a performer and actress she toured the world along with other small performers such as ‘Commodore Foote’ and his sister the ‘Fairy Queen’. Although she never married it appears that she did have a liaison with a Commodore Nutt.

A reviewer described Quigley as ‘a charming mite of femininity who captured the hearts of everybody by the perfection of the acting as well as by her personal beauty and naturalness of character’. She retired in 1917 after fifty years in showbusiness.

Angus Mor MacAskill was born in 1825 on the Isle of Berneray in the Sound of Harris. He was rated by the Guinness Book of Records as the tallest non-pathological giant in history, standing at 7ft 9in.

At an early age he moved with his parents to Canada as a ‘normal’-sized child. It was only when he reached adolescence that he had a prodigious growth spurt. He quickly became known for his astounding strength. He could lift a ship’s anchor weighing 2,800lb – over a ton. He could carry a 350lb barrel under each arm and it was claimed that he once lifted a horse over a 4ft fence.

In 1849 he started working for P.T. Barnum’s show, appearing alongside the tiny ‘General Tom Thumb’. He toured many parts of the world, including a requested performance in Windsor Castle for Queen Victoria. After retiring from showbusiness he settled in Englishtown in Nova Scotia where he died at the tragically young age of 37. His death came in the year before Jennie Quigley arrived in America, so the two Scottish superstars never met.

There are two museums dedicated to Angus Mor MacAskill, one in Englishtown and one, set up by Peter MacAskill, in Dunvegan on the Isle of Skye.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s grandfather was also Robert Stevenson. Robert Stevenson’s life changed when his mother, who had been widowed young, remarried. Robert’s step-father, Thomas Smith, was an engineer. He took the boy on as an apprentice and later as a partner.

In 1791, at the age of 19, he was trusted with the supervision of the construction of a lighthouse on the island of Little Cumbrae on the Clyde, followed by a lighthouse on the Pentland Skerries. While, in a long career, he also designed roads, bridges and railway lines, lighthouses became his speciality. He designed over fifteen of them all around the coast of Scotland. Several of his innovations became standard across the world.

The lighthouse-Stevenson connection did not end there. All three of Robert’s sons designed lighthouses: David was responsible for over thirty; Alan for thirteen; Thomas another thirty. David’s two sons, David and Charles, added another thirty to the tally. Well over 100 in all, keeping shipping safe around the Scottish coast from Muckle Flugga to St Abbs Head, from the Butt of Lewis to Girdleness. A remarkable engineering dynasty.

Thomas’s son, Robert Louis, was a huge disappointment to his family. He constructed some of the best loved literature of his age. But lighthouses? Not one!

William Brodie was a Deacon of the Guild of Wrights and a member of the Town Council. He had a respectable reputation in Edinburgh. He also had five children, a mistress and a gambling problem. Keeping up appearances was expensive. He realised that his position allowed him to visit wealthy houses and case the joints. Alongside cabinet making, he also ran a locksmith business giving him access to keys to copy. He had a distinct advantage in his secondary career as a burglar!

He had three accomplices to help his night-time personality: Brown, Smith and Ainsley. His most daring raid was also his last. The target was His Majesty’s Excise Office in the Cannongate – it was a disaster. Ainsley and Brown were caught. They quickly turned King’s Evidence and Brodie was arrested and duly sentenced to hang.

There are two strange stories connected with the execution. One is that Brodie, a man of good standing, had himself recommended improvements to the gallows, introducing a forward-thinking drop mechanism to replace the old ladder. Tradition has it that he was the first person to feel the benefit of the new system.

The second story is that Brodie contrived to survive the hanging. The details are a bit hazy. The hangman was bribed to shorten the rope to stop his neck being broken. Brodie lodged a silver tube in his own throat to stop his windpipe being crushed, or perhaps it was an iron collar. A doctor was waiting to revive him when he was rushed from the gallows. All was to no avail and Deacon Brodie was indeed hanged to death.

A century on, R.L. Stevenson wrote the play Deacon Brodie: A Double Life and later took up the double-life theme in the much more successful Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

While in Samoa, Robert Louis learned that Annie, the young daughter of an American friend, was upset that she had been born on Christmas day. This meant that she never got a proper birthday as it was lost in the annual celebrations of that day. He had proper legal documents drawn up and witnessed, gifting his birthday on 13 November to Annie. She used that date for the rest of her life.

When plans were made to erect a prominent monument to Sir Walter Scott, the design was to be chosen by competition. A young carpenter drew a design in just five days and won the contest.

George Meikle Kemp, who grew up in Carlops in the Borders, had no architectural training but he did have a passion for ancient buildings. He taught himself the skill of technical drawing and recorded many buildings in the Borders and later in Glasgow. His particular favourite was Melrose Abbey.

When the competition was announced he produced a design borrowing heavily from the style of Melrose Abbey. He submitted the drawings under a pseudonym. Out of fifty-four entries he came third. The committee, however, were not agreed on the final choice. The top entries were asked to revise and resubmit. George Meikle Kemp came out on top.

His vision dominates Princes Street today. Sadly, he didn’t see it completed. One foggy evening he fell in the Union Canal and drowned.

There is a monument to George a few miles north of Peebles on the Edinburgh Road. It is somewhat less grand than the one he designed for Sir Walter.