We have no documents from our early history to help us establish the facts. We have to read the bones and the stones. What the bones and stones say is not always clear.

The Toilet Guru (yes, there is one, he has a website) claims that the top candidate for the world’s first recorded indoor toilet is at Skara Brae on the Orkney mainland. Archaeologists are, as usual, not prepared to give a definite answer, but they are not denying that the drainage systems in some of the buildings could be the first lavatories.

Skara Brae was a remarkable discovery. It was naturally preserved under sand for thousands of years until in 1851 a storm blew away enough sand to reveal the secret. A 5,000-year-old village was unearthed in exceptional condition. The stone rooms give us a real sense of what life might have been like in the Stone Age; they were equipped with beds, seats and dressers.

We think of the islands as being remote and hard to reach, but in the past the sea was the highway. Places like Shetland, Orkney and the Hebrides were not on the edge: they were at the centre. Neolithic constructions such as the Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar on Orkney and the Callanish Stones on Lewis (all older than Stonehenge) tell the story of a well-organised and disciplined society.

The writer and historian Brian Aldiss said that, ‘the degree of civilisation can be measured by the distance man puts between himself and his own excrement’. Why should that sophisticated Orcadian society not invent the loo?

It is commonly thought that Thomas Crapper invented the flushing toilet. The Toilet Guru poo-poos this idea. The first flush was created by Englishman Sir John Harrington, a courtier of Elizabeth I. He was also famous for writing bawdy verse. It was not until 1777 that an Edinburgh watchmaker, Alexander Cummings, patented the design that we still use today. The critical element was the ‘S bend’ which traps water below the bowl, preventing smells drifting up from the pipes beneath.

Scotland’s contributions to the worlds of science, engineering and even cuisine have outweighed the size of our population. Among the things Scots can claim to have invented, or discovered, are: adhesive postage stamps; anaesthetics; antiseptics; advertising films; the agricultural reaping machine; Bakelite; Brownian motion; chemical bonds; chicken tikka masala; the cure for scurvy; the decimal point; fax machines; flailing machines; golf; the historical novel; hypodermic syringes; iron bridges; the Kelvin scale of temperature; logarithms; marmalade; Mackintosh raincoats; microwave ovens; paraffin; the percussion cap; penicillin; pneumatic tyres; postcards; quinine; radar defence; refrigerators; the steam engine; the steam-hammer; sulphuric acid; tarmacadam; the telephone; the telegraph; the television; and, of course, the deep-fried Mars bar.

By the way, the Neolithic cairn on Orkney, Maeshowe, was raided by Vikings. While sheltering from a snowstorm they amused themselves by inscribing graffiti on the walls. Some of it is very rude. The inscriptions include a reference to Ragnarr Loftbrok, the character fictionalised in the recent TV series ‘Vikings’.

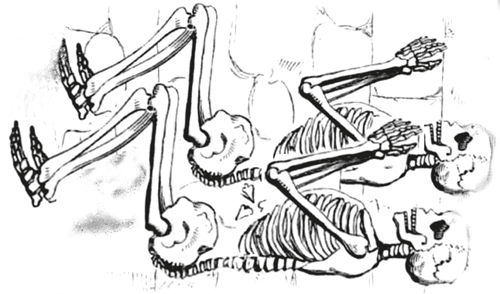

A 2001 excavation on the Isle of South Uist unearthed an astounding mystery. At Cladh Hallan two skeletons were discovered, presumed to be from the Bronze Age. The skeletons were from a man and a woman, both buried in a foetal position. So far, so good. It was when they started to examine the bones that things started to go awry. One skeleton with clearly a female torso appeared to have the skull of a man. When the DNA and other test results started coming in things got really weird. Not only did she have a male skull, but her arm also belonged to someone else! The three people weren’t even closely related.

The male skeleton was no less surprising, bones in his skull, neck and torso belong to three different people. Stranger still, isotopic dating showed that the male mummy is made from people who died a few hundred years apart. The skull on the female turned out to be 50–100 years older than her torso.

Further test results showed that the bones had spent some time in a peat bog before being retrieved and re-buried. It seemed that the natural processes in bogs whereby organic material is preserved were being harnessed in a form of a mummification process. ‘Mummification has been surprisingly widespread throughout world history, but this is the first time we’ve seen clear evidence that it was employed during the Bronze Age on the British Isles,’ said University College London archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson. The weird couple were labelled by the press as the ‘Scottish Frankenstein Mummies’.

In peat bogs the rotting of most organic material is inhibited, however this doesn’t apply to bone because of its calcium content. This explains why most bog bodies look like saggy leather sacks. They are literally spineless. In the Cladh Hallan case it appears that the bodies were ‘bog mummified’ for long enough for the flesh to be preserved, but not so long as to let the bones decay. The fact that the bones, within each section, were still attached to each other indicates that there must have been flesh present when they were moved to the burial site.

So it appears that different parts of six mummies of different ages were reassembled as two bodies and given a proper Bronze Age burial. The question is, why?

There are theories, but no answers. The archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson of UCL suggests, ‘The mixing of remains could have been designed to combine different ancestries or families into a single line of descent. At the time, land rights would have depended on ancestral claims, so perhaps having ancestors around “in the flesh” was the prehistoric equivalent of a legal document.’

Professor Terry Brown, of Manchester University, suggests that maybe they weren’t too good at mummy management: ‘Maybe the head dropped off and they got another head to stick on.’

Another possibility is that the merging was deliberate, to create a symbolic ancestor that literally embodied traits from multiple lineages. We wondered if it could be that someone came across a cache of bog bodies, which they had nothing to do with, and just did the decent thing by giving the bits they could find a proper burial.

![]()

By the time we get to the Iron Age we have a new resource – oral history. Myths (or are they legends?) gathered into epic sagas were passed down through generations by word of mouth. Each generation added its own embellishments so that the heroes got more heroic, the villains got more villainous and the underlying current of magic got more, well, magical. There have always been those who have argued that beneath the fantastical veneer lay real stories about real people, making these ‘legends’ (stories with a factual basis) as opposed to ‘myths’ (stories with a fictional basis). Others have scoffed, dismissing the sagas as mere fantasies. In recent years more and more archaeologists have been reviewing the material and finding, more and more, that the stories and the physical evidence support each other, and vice versa.

The Irish sagas are particularly rich, but they are full of relevance for Scotland. The Cuillin mountains on the Isle of Skye are named after the Irish legend Cuchullin, demonstrating how close the links across the North Channel were even 2,000 years ago. Cuchullin is a leading figure in the ‘Ulster Cycle’ which described events that happened ‘around the time of Christ’. This is supported by recent archaeology. The central location of the saga is the fort of Emain Macha which has long been identified as Navan Fort just outside Armagh. Dendrochronology studies (tree-ring dating) of the centre post of an Iron Age roundhouse excavated at Navan give a date of just after 100 bc.

In the stories Cuchullin, already quite successful in martial arts, comes to Scotland to further his education. He attends a university of violence on the Isle of Skye under the tutelage of the warrior queen Sciatach. While there he meets Ferdia, his best buddy (until Cuchullin slaughters him). He also gets involved in a skirmish with a second warrior queen, Aoife. The two find themselves in a clinch where they stare into each other’s eyes. Shortly afterwards, Aoife finds herself pregnant and Cuchullin returns to Ireland. Their boy, Connla, visits Ireland years later and is challenged on the beach by his father. Following instructions left by Cuchullin for his infant son, Connla refuses to give his name or to back down. Cuchullin murders his own son. It didn’t pay to get close to this man. His potential Scottish lineage didn’t last long.

In the later cycle of Fionn MacCumhaill (Finn MacCool) stories, in some versions of the story of Fionn’s pursuit of Diarmud, who had run off with his wife Grainne, the events end dramatically in Glen Etive. Local place names seem to support this.

Tales of Cuchullin and Finn MacCool featured strongly in West Highland oral traditions until recent times.

In the years from 1761 Scots poet James MacPherson, from Ruthven near Kingussie, published translations of ancient Gaelic manuscripts. The stories were written in the voice of Ossian, telling the tales of his father, Fingal. Clearly these were tales related to the stories of Fionn MacCumhaill and Oisin, his son.

The collection of poems was very successful and was translated into several languages, but there was doubt from the start. Samuel Johnson described MacPherson as ‘a mountebank, a liar and a fraud’. It does have to be said that Johnson also described the Gaelic language as ‘the rude speech of a barbarous people’.

It is now accepted that while finding inspiration amongst songs and scraps of ancient literature, MacPherson largely made Ossian up himself. The collection has been described as ‘the most successful literary falsehood in modern history’. It is still an impressive piece of work.

When I first moved to Peebles in the 1980s I heard it said that names like Peebles and Penicuik were Welsh. It was commonly known. However, a little research quickly turned this on its head.

When the Romans came to Scotland, the tribe occupying an area equivalent to much of the Borders and Lothians were called the ‘Votadini’ by the Romans. They were Bretonic Celt, very distinct from the Gaelic Celts of the Highlands. After a few skirmishes they decided, as so many peoples across Europe had, that getting on with the Romans was the better option.

The Romans, impressed by their warrior skills, offered them extensive territory farther south and to the west of Roman Britain. The job was to keep the locals quiet and resist Irish pirates. The Votadini, or Gododdin as they called themselves, took up the challenge.

Moving to North Wales, they had a huge influence on local language and culture. Contacts between the two regions were maintained, as indicated by the fact that the best history of the tribe was written by the Welsh poet Aneirin. The poem ‘Y Gododdin’ (the date of which is uncertain, but the events described are reckoned to be late sixth–early seventh centuries) tells stories of the Gododdin partying in Dun Eidyn (Edinburgh) for a year before heading out to a battle at Catraech – which is interpreted as Catterick. The force includes fighting men from different southern Scottish regions, as well as men from North Wales. The battle was a disaster for the allied troops. ‘Y Gododdin’ also contains possibly the first known reference to King Arthur.

What Wales, the West Country and Southern Scotland had in common was Bretonic Celt ancestry, the true ‘British’ in fact. Aneirin’s poetry reveals that there were not just cultural but also political links between these areas. It is not surprising that such a good story as the hero warrior King Arthur should travel about a bit.

Borders folklore has long owned Arthur and, more particularly, Merlin. Arthur and his knights lie in a secret cave in the Eildon Hills waiting only for the signal to rise and defend Britain again. Should you stumble upon the cave you will be presented with the choice between a horn and a sword – ‘woe betide the coward who picks up the horn before the sword’. You have been warned!

Merlin, too, may be trapped in a cave in the Border hills or he may be buried at Merlin’s Grave in Merlindale, would you believe? (The place names are a bit of a giveaway, take Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh, for example.) Merlin died by ‘falling, stabbing and drowning’ as he himself predicted. Chased by shepherds, he tumbled into the River Tweed where he was impaled on a structure for salmon fishing, trapped underwater, and drowned.

These associations with Merlin and Arthur are not a new discovery. In the thirteenth century Thomas the Rhymer mentions Merlin’s Grave (at the site commemorated by a thorn tree today) in a prophesy:

When Tweed and Powsail [Burn] meet at Merlin’s Grave

Scotland and England shall one King have.

Naturally, on the date James VI became James I of England, a huge flood in the named river and burn inundated the grave.

Further local tradition tells of Merlin’s conversion to Christianity. After leading a pagan army against the Christian forces of Strathclyde and losing badly, he was baptised by Saint Kentigern. The altar stone used in the ceremony is kept in Stobo Kirk (near Peebles) as proof and a stained-glass window celebrates the event.

This Christian element may be a later addition to the Bretonic tales, but then so is just about everything we know about Arthur and Merlin. The shining armour, the sword in the stone, the round table, the Lady in the Lake, Lancelot, Guinevere and Mordred are all later add-ons. Geoffrey of Monmouth, in the twelfth century, was influential but it was Thomas Mallory’s fifteenth-century Le Morte D’Arthur that crystallised the popular notions of King Arthur.

The truth of Arthur’s origins lies in a mosaic of Bretonic tribes warring with each other and with Picts and Angles, overlaid by folklore and scant documents along with archaeological remains (much of it unexplored). Alistair Moffat’s 1995 book Arthur and the Lost Kingdoms explores all this in depth. The case for a Scottish Arthur stands strong.

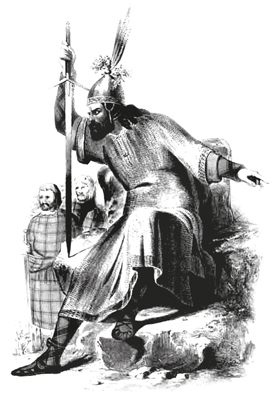

Somerled (pronounced Sorley) has gone down in history as the great Gaelic Viking hunter. Legend has it that when a Viking war party landed in Argyll, Somerled was fishing. He was sent for but refused to move until he caught the salmon he was angling for (being a keen fisherman I find this entirely understandable). Thankfully he did land the fish and headed for the battle. He struck down the first attacker he came across, split open his chest and ripped out his heart. He charged into the fray brandishing Norwegian offal.

Somerled’s grandfather, Gilledomman of the Isles, had been defeated by the Norse and exiled to Ireland. When he was a child, Somerled’s more immediate family was also expelled from their home and sent to Ireland. His father Gillebride raised an army of 500 and returned to Morvern to regain their lands, but was beaten off and killed. Around 1135 Somerled led a successful rebellion which cleared Norse control from Morvern, Lochaber and much of Argyll. He became the Thane of Argyll.

In 1158 he took on the unpopular King of Mann, Godred II or Godfrey the Black. The Kingdom of Mann controlled much of the sea between Britain and Ireland. It was a Norse kingdom, paying homage to the Kings of Norway. In a decisive sea battle using galleys equipped with rudders, the latest in naval technology, he defeated Godred.

Somerled declared himself ‘Ri Innse Gall’ or Lord of the Isles, effectively setting up an autonomous state, the Lordship of the Isles, which was independent of both Norway and Scotland. This institution was to last for three centuries, ending in 1493, when John MacDonald was forced to forfeit his land and titles to James IV (he had been plotting with the English King Edward VI to invade Scotland).

By the way, the title ‘The Lord of the Isles’ still exists. The current holder is Prince Charles. Charles is also the Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick, Baron of Renfrew and High Steward of Scotland.

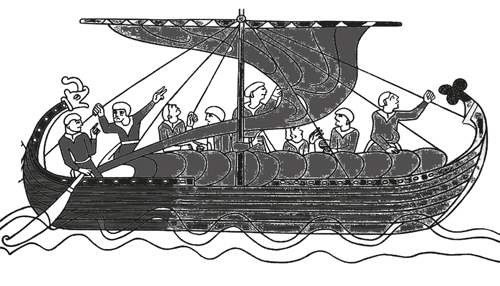

It is recorded in the Saga of Erik the Red that Leif Ericsson discovered America around AD 1,000 by accident when he was blown off course on a trip to Greenland. He called it Vinland on account of the berries he found.

Four years later Thorfinn Karisefni led a new expedition to explore this promised land of wine. Among a crew of around 160 on three ships were two Scots. They were slaves – a man named Haki and a woman named Hekja. They had a reputation as fast runners and so were landed with instructions to make their way along the shore, while the rest of the expedition followed offshore in the safety of their ships. The couple were being used as bait so that any unfriendly natives would reveal themselves. None appeared so the Norse came ashore. The expedition did later encounter hostiles, but did not find much in the way of ‘wine berries’. After three years they abandoned the continent.

![]()

In the thirteenth century a fight was brewing. King Haakon IV of Norway and Alexander II of Scotland were ambitious men; both were keen to stamp their authority over the islands and the seaway between Scotland and Ireland. Battles had long been fought between Scots and Norse but there had been no decisive fixture. A showdown was called for.

Haakon mustered his forces in Orkney and sailed down though the Hebrides, reaffirming allegiances and gathering forces as he went. By the time he reached the Clyde he was said to have up to 120 ships and 20,000 men. A massive force. Alexander knew he had no chance in an open sea battle. He drew out negotiations with Haakon’s envoys and waited until his secret weapon was deployed – the Scottish weather!

On 1 October the storm hit. It was sudden and violent. Haakon’s fleet was shattered and many ships were driven ashore. The next morning a bedraggled Haakon was ashore with about 1,000 men near Largs. It was then that Alexander’s men attacked. It was not a huge victory for either side, but it was effectively the last great battle between Scotland and Norway and the end of Viking power in the area.

Haakon escaped back to Orkney. Or did he? Local tradition had it that he died in the battle and was buried nearby. ‘Haakon’s Tomb’ is a well-known landmark in the town of Largs. Closer examination reveals that the monument is actually a Neolithic chambered tomb and was built around 4,000 years before the Battle of Largs.

The other story tells that Haakon made it back to Orkney, where he died two months later. After three years Haakon’s son, Magnus IV, relinquished his claim to the Hebrides and the Isle of Man for 4,000 silver merks in the ‘Treaty of Perth’.

By the way, when a monument commemorating the battle was planned for Largs, the planners made no decision as to how high it was going to be. Built in 1912, the Pencil Monument is a simple round tower. The builders put the money for the roof aside and kept fundraising while the tower was under construction. They kept building as long as the money kept coming in.

It was the monks who, in the seventh–tenth centuries, wrote down the stories that had been in the oral tradition for the best part of 1,000 years. The documents concerned are the Annals, and are intended to be the reliable history of the time. In some cases the documents are compilations of earlier documents or collections of information harvested from them, sometimes spanning centuries. The Annals of the Four Masters record events from the earliest times up to the seventeenth century. They are the most authentic records we have of the early period, and much of what is known of the so-called Dark Ages depends on these books.

The past throws up some truly unbelievable stories. But what can we believe? Surely documentary evidence is helpful, but history being what it is, it is advisable to find more than one source for any story. This is a dictum we have stuck to religiously in compiling this book.

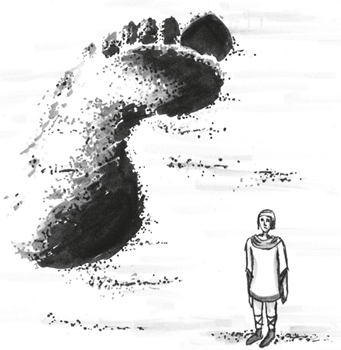

This story has not two, but four sources. Given that the event occurred in what we call the Dark Ages, when documents are very few and hard evidence of any kind is hard to come by, this level of agreement is astounding. Surely this must be fact.

The story is of a woman washed up on the shores of Scotland. She had very pale skin, long hair and was nearly 200ft tall! There are slight discrepancies in the measurement, suggesting that it wasn’t all just copied from a single origin. It would make no sense to change a measurement by a few feet.

The Annals of Ulster (ad 891) records: ‘The sea threw up a woman in Scotland. She was a hundred and ninety-five feet in height; her hair was seventeen feet long; the finger of her hand was seven feet long, and her nose seven feet. She was all as white as swan’s down.’ This is very similar to the story which appears in the Annals of the Four Masters (ad 891) but with a different length of hair.

The Annals of Innisfallen (ad 906) says, ‘A great woman was cast upon the shore of Scotland in this year. She was a hundred and ninety-two feet in length; the length of her hair was sixteen feet; the fingers of her hand were six feet long, and her nose was six. Her body was as white as swan’s down, or sea foam.’

Chronicon Scotorum (ad 900) which admits that it had copied the story from the Annals of Tigernach, notes, ‘A great woman was cast ashore by the sea in Scotland; her length 192ft; there were six feet between her two breasts; the length of her hair was 15ft; the length of a finger on her hand was six feet; the length of her nose was 7ft. As white as swan’s down or the foam of the wave was every part of her.’

Make of it what you will.