The sixteenth century has been described as the beginning of the modern world. It began with the scientific curiosity of James IV and ended with the burning of witches by James VI. In between was the tangled and tragic life of Mary, Queen of Scots.

When James V said ‘It came with a lass, and it will pass with a lass’ on the birth of his daughter, Mary, he was referring to the Stewart dynasty. The lass that started it was Marjory Bruce, daughter of Robert the Bruce, who married Walter Stewart, giving the family the right to the throne. He was predicting that his daughter’s reign would see the end of it. He was spectacularly wrong. Mary’s son (who she barely knew as he grew up) was to become James I of England. Stewarts would be monarchs of both Scotland and England for another 165 years (with a slight interruption).

By the way, the ‘Stewarts’ were now ‘Stuarts’. The change of spelling was made by Mary so as to make it easier for the French to pronounce correctly.

James V was also right. The Stuart reign did indeed end with a lass: Queen Anne, daughter of James VII. She was pregnant seventeen times, but died without any living children. Anne’s brother, James Frances, was excluded as he was a Catholic. This led, through a complicated calculation, to the arrival of the German House of Hanover and a long succession of Georges.

![]()

Mary, Queen of Scots’ life was certainly strange. Queen at the age of six days, she was brought up in the French court and was engaged to a French prince (who died). She arrived in Scotland to find herself regarded as the enemy by the English and quite a few Scots. Her husband, Darnley, murdered her friend, Rizzio. Darnley was then murdered. Mary dashed off with one of her husband’s murderers, Bothwell. She was imprisoned on an island in Loch Leven. She escaped and fled to England where she was kept a prisoner for nineteen years before her strange and gruesome death.

Since then she has been a very busy lady. Ghosts are often said to be restless spirits and Mary’s is more restless than most. During her travails in Scotland and her detention in England she stayed in many castles and grand houses. Apparently, at many of them she is still there.

Stirling Castle was a familiar place to her; she allegedly remains there in a pink dress (the one in the green dress is a maid who rescued her mistress when her bed caught fire). Her ghost lingers on the isle in Loch Leven. At Borthwick Castle, where she stayed with Bothwell, a spectral boy appears and, yes, it’s Mary again wearing the disguise in which she escaped the castle. Bothwell connects her to Hermitage Castle, which she haunts – even though she never stayed there! She appears, headlessly, at Craignethan, near Lanark. She may, or may not be, the white lady who appears on the stairs at Craigmillar Castle. This Mary only appears when it’s raining heavily outside!

During her English adventures she was kept at Bolton Castle, where she still wanders around the courtyard. At Nappa Hall in Yorkshire she wears a black gown. She also walks through walls in the Earl’s Manor Lodge in Sheffield.

Fotheringay, the place of her execution, is a likely candidate for a ghost, but it was destroyed in the seventeenth century. Enterprisingly, when stones and timber from the castle were used to build a hotel nearby, Mary’s ghost went with them.

Mary, Queen of Ghosts!

![]()

In 1551 English Crown Officers declared:

All Englishmen and Scottishmen, after this proclamation made, are and shall be free to rob, burn, spoil, slay, murder and destroy all and every such persons, their bodies, buildings, goods and cattle as do remain or shall inhabit upon any part of the said Debateable Land without any redress to be made for the same.

The Scottish king had no objection.

The said ‘Debatable Land’ was the area bounded by the River Esk and the River Liddel on the one side and the River Sark on the other. The whole of the area around the Scotland/England border was lawless, but neither country had any semblance of authority in this region.

The Border Clans had their own law. Their occupation was ‘reiving’: stealing – cows mainly, but whatever came to hand. They were happy to raid north or south from their strongholds.

By the way, the word ‘blackmail’ came from the Border reivers. It referred to the protection rackets they ran – ‘pay up or lose yer coos or yer heid’.

Armstrongs, Kerrs, Elliots, Grahams, Humes and Bothwells had little regard for either king. The Armstrongs were one of the strongest families: they claimed to be able to muster 3,000 armed men. In 1530 King James V took action. He went hunting.

James set off, with an entourage suitable for his purpose, to Ettrick Forest (pretty much Selkirkshire today).

By the way, a ‘forest’ denotes a hunting area; trees are in no way implied. Much of the Highlands were given over to ‘deer forests’, when often there was not a tree in sight.

The king camped at Caerlanrig on the River Teviot. He issued an invitation to the Border gentlemen to join him there. Here was an opportunity for reconciliation. If they were prepared to swear their loyalty all would be forgiven.

Young Johnnie Armstrong of Gilnockie, son of the Armstong chief, was sufficiently reassured about his safety that he set out from Langholm Castle with a party of fellow Borderers. The numbers vary from different accounts: there may have been as many as fifty of them, some accounts mention twenty-four; a couple of dozen seems a reasonable number to us.

For such a prestigious occasion the men turned out in their finest clothes and the likes of Johnny Armstrong were not short of cash. The sight of the well-dressed, handsome, confident young man was only a further annoyance. The king was later to say that the reason Johnny Armstrong was killed was because he was better dressed than himself and that was a show of disrespect.

Armstrong’s men were intercepted by horsemen before they reached Caerlanrig; it was clear that James hadn’t come loaded for deer. Confronted by the king, it was pretty clear that forgiveness was not on the agenda. Johnny claimed that he had only ever raided the south, only robbed the English, to which a modern Glaswegian might reply, ‘Aye, right!’ (Much has been made of the grammatical incorrectness of the double negative, but ‘Aye, right!’ is a rare expression that proves that two positives can make a negative.)

The Borderer did not plead for mercy but rather tried to bribe the king. He could afford it. Armstrong is supposed to have said, ‘I am but a fool to seek grace at a graceless face, but had I known you would have taken me this day, I would have lived in the Borders despite King Harry (Henry VIII) and you both.’

James hanged the entire Borders party. The game book for the outing might have read, ‘Deer –nil, Borderers – twenty-four’.

By the way, the site of the mass grave where they were deposited was unknown until the 1980s when a farmer tilling opposite Caerlanrig church unearthed a large stone with marks on it. Subsequent explorations by dowsers and by archaeologists agreed that there are bodies beneath the spot.

When James VI of Scotland became James I of England he envisaged a united nation. The Border was redundant and the Borderers an embarrassment. They were a threat to travel and to commerce between two parts of his domain. Since that domain stretched from Land’s End to John O’Groats, the Borders were halfway down. He rechristened them the ‘Middle Shires’.

James commenced a thorough campaign, destroying strongholds and executing or displacing many of the reivers and their families.

Although not part of the official plantation, many of those displaced ended up in Ulster. A range of Borders names are common in Northern Ireland today.

![]()

At school we both hated John Napier, although we had never heard his name. He was the inventor of schoolchild torture in the form of logarithms and the decimal notation for complex equations. While we were totally bewildered trying to make sense of these dancing numbers they were, for mathematicians and for all the other disciplines that depend on hard sums, a godsend. He went further with the invention of Napier’s Bones, an early calculator, and then followed this with the creation of rabdology, literally ‘rod calculation’. The Babbbage Institute has reproduced his work in their history of computing.

His work was revolutionary. His discoveries were right up there with the likes of Galileo and Newton. Scottish intellectual David Hume described him as ‘the person to whom the title of great man is more justly due than to any other whom this country has produced’.

At a time in history when any hint of witchcraft was highly dangerous, he was widely rumoured to be a warlock and sorcerer. Dangerous too was being caught on the wrong side of the Protestant/Catholic divide when the followers of Queen Mary were trying to promote the old religion and the forces of the Reformation were trying to stamp it out. At 17 he was forced to study abroad, having left St Andrews University prematurely after his friendship with a Catholic student brought him under suspicion.

He was later to establish his Protestant credentials by publishing an investigation of the biblical prophecies of Armageddon. His conclusion was that the Pope was in fact the Anti-Christ. He went on to write a series of religious tracts which were translated into several languages and sold well across Protestant Europe.

He returned to Edinburgh in 1571 to find his father imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle by the Queen’s party, while the family home at Merchiston was occupied by the forces of the regent. The following year Merchiston was bombarded by the guns of Edinburgh Castle.

Retiring from Edinburgh, he built a new house for himself and his young wife at Gartness on the banks of the River Endrick. Elizabeth Stirling left him one child before her premature death. His second wife, Agnes Chisholm from Perthshire, gave him five sons and daughters.

The rural retreat gave him peace to get on with his studies, but Napier’s genius was interpreted as foul black wizardry. Rumours of witchcraft grew. He did very little to discourage it; dressed in a long black cloak, with a long black beard, he looked the part. Added to this he openly kept a ‘familiar’ in the form of a large black cockerel. There is a story that when it was suspected that one of the servants was stealing from the household, he gathered the staff together and bade them stroke the rooster. The bird would identify the guilty party by crowing. He left them to perform the ritual in private. The cock did not crow but Napier quickly identified the thief. He had taken the precaution of spreading soot on the bird’s back. The one with clean hands, the one who had not dared stroke the bird, was judged guilty.

He went on to turn his agile mind to agricultural improvement and to military technology. When the Spanish invasion threat was at its height he published Secrete Inventiones in which he outlined plans for a giant mirror to burn enemy ships by focusing the sun’s rays on them, a man-powered tank, a submarine, and a form of artillery which could clear a field of anything standing over a foot high. None of the ideas ever went into production – he was way ahead of his time.

John Napier is remembered at Napier University in Edinburgh. The university’s buildings include Merchiston Tower where he was born.

![]()

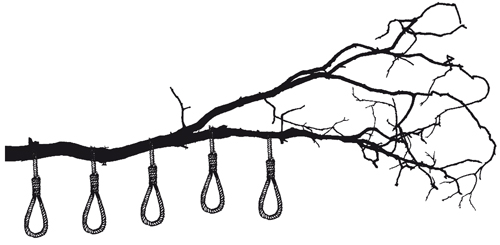

The Scots embraced the sport of witch hunting, burning, hanging and drowning more wholeheartedly than other parts of the British Isles. This may have a lot to do with King James VI. He became something of an expert on the subject of witchcraft, even writing a book on the subject, Daemonologie.

The whole craze really kicked off with the North Berwick Witch Trials in 1591.

James was in Denmark, picking up his wife, Ann of Denmark. His return to Scotland was postponed repeatedly by bad weather. Eventually they made the crossing only to be assaulted by a violent storm while within sight of home. They only just made it to harbour.

It turned out that a party of witches had gathered in North Berwick. They had a cat which they ‘christened’ James and passed back and forth over the flames of a fire. They set sail to intercept the king’s ship in sieves. They were able to listen to conversations on board the vessel. They threw the cat into the sea, conjuring the tempest which nearly sank the king.

Now this might seem strange, but the fact is that this was presented as evidence in a Scottish court. James paid close attention to the whole affair. He did, after all, know a thing or two about the subject. He had during his recent visit to Denmark spent time with renowned witchcraft expert Peter Munk. Thoughts of the things he had learned were fresh in his mind when that storm hit.

Gillis Duncan, a serving girl from Tranent, who had a small reputation as a healer with some knowledge of herbs, was arrested. Under extreme torture she started naming names: Agnes Sampson, an old lady from Haddington; Agnes Tompson of Edinburgh; Dr Fian, a schoolteacher from Saltpans; George Mott’s wife; Robert Grierson, a skipper; and Jannet Blandilands. There was more torture and more names emerged. By the end of a two-year trial over seventy people had been implicated.

Strangely, the one suspect who might have been guilty of conspiring against the king was the one who got away: Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell. He had already been found guilty of conspiring to seize James (his first cousin) at Holyroodhouse two years earlier.

Bothwell was accused of bursting open the door to North Berwick church using a ‘Hand of Glory’. A ‘Hand of Glory’ is the hand cut from a hanged man on the gibbet. When the fingers are lit, like a five-pointed candle, it becomes a powerful magical weapon. Witnesses then described the demonic service conducted by a masked man – Bothwell. Bothwell was arrested but escaped from prison and was declared an outlaw.

In 1593 he forced his way into the royal bedchamber and somehow got the king to grant him a full pardon. His forfeited lands and titles were returned. A trial, regarded by many as a farce, saw him acquitted of the witchcraft charges.

He was later exiled and died in Naples, but he certainly did fare a lot better than many of the others in the trials. Dozens were executed by garrotting, hanging and burning.

The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft has identified 3,837 people accused of witchcraft in Scotland, but admits that this may not be complete. It is unclear how many were executed. In some cases, notably the North Berwick one, torture was used until a confession was forthcoming. There are cases where a conviction was secured on the grounds that the accused did not confess. It was argued that they could only have withstood the pain by means of magic: Catch 22.

In 1727 Janet Horne, an elderly woman from Dornoch in Sutherland, was accused by her neighbours of witchcraft. It was said she could turn her daughter into a pony and ride her around in the night. Deformities of the poor girl’s hands and feet were cited as evidence.

Janet and her daughter were tried and found guilty. The daughter escaped but the mother was smothered with tar, carried through the town on a barrel and burned to death. Eight years later the law regarding witches was changed.

A small stone monument stands at the spot of her execution. The stone carries the incorrect date 1722.

Helen Duncan from Callender was tried at the Old Bailey under the Witchcraft Act of 1735 in 1944. Helen was a well-known fortune teller, astrologer and spiritualist. Arrested following a séance, she was accused of pretending ‘to exercise or use human conjuration that through the agency of Helen Duncan spirits of deceased persons should appear to be present’.

She was not, as reported in the press, tried as a witch. In fact the 1735 Act intended to stamp out belief in witchcraft among the general population. Its introduction meant that from 1735 onwards an individual could no longer be tried as a witch in England or Scotland. However, they could be fined or imprisoned for purporting to have the powers of a witch.

During the case she was asked if she could demonstrate her powers from the dock: effectively conduct a séance in the courtroom. She declined. Helen was convicted and sentenced to nine months in prison.

James VI was keen on the idea of plantation; simply move a substantial number of people who are sympathetic to you into an area and let them do the job of subduing the natives. This was cheaper than sending in an army and you can, in due course, tax the new settlers.

It is well-known that James supported the plantation of Ulster and Virginia, but he also attempted to plant Bermuda and, bizarrely, the Isle of Lewis.

In 1597 Torquil Dubh MacLeod had failed to comply with the Act of Estates, which compelled everyone who claimed to own land in the Highlands and Islands to produce documentary proof. This left the Isle of Lewis technically ownerless. In 1598 the land was granted to a consortium of businessmen from Fife headed by the Duke of Lennox. They were given seven years rent free to allow them time to establish themselves.

The object was to civilise the natives who were described as guilty of ‘the grossest impiety and the most atrocious barbarities’. Commissioners were given authority to punish by ‘military execution’ anyone who opposed the occupation – either openly or tacitly.

In 1599 the first expedition arrived with a few gentlemen and the builders and tradesmen needed to start construction of the new settlement. They also brought over 500 hired soldiers.

One of the leading Fifers, James Leirmonth, was captured by Murdoch MacLeod when he tried to sail back to Fife and held prisoner until a rich ransom was agreed. Leirmonth, however, died from illness contracted during his captivity and the ransom was never paid. Murdoch’s brother, Neil, was persuaded by the settlers to hand over his brother. Murdoch was duly executed in St Andrews.

Peace did not last long. The settlement was attacked, the fort burned and many were killed. The MacLeods demanded that the Fifers leave, never to return, and that the islanders should receive a pardon for all crimes. Hostages were held.

It was not until the summer of 1605 that the Fifers returned. They were armed with:

Commissions of fire and sword … to search, seek, take and apprehend the aforesaid persons, rebels and fugitives … and execute them to the death; and, if need be, to raise fire and sword and to burn their houses and slay them in case they make opposition or resistance in the taking and apprehending.

They also had a few of the king’s ships and an armada of commandeered vessels. They re-established the settlement, but Neil MacLeod did not go away. Under continuing relentless harrying from the natives the whole project slowly crumbled.

By the way, Fife is properly referred to as the ‘Kingdom of Fife’ (not ‘County Fife’ as Johnny Cash described it; apparently that’s where his ancestors came from). The origins of this appellation are somewhat obscure, as is the question ‘Who is the King of Fife?’

Waiting in the wings was Kenneth MacKenzie of Kintail who had long had his eye on Lewis. He stepped in and bought the commission for Lewis from the remaining Fife businessmen for a sum of money and an iron mine in Letterewe. In 1609 MacKenzie, with 700 men, ruthlessly cleared Lewis of opposition, succeeding where the Fifers had failed.

Neil Macleod retreated to the tiny island of Berrisay with a group of loyal men. For three years they held out on this impregnable rock. When his patience ran out Roderick MacKenzie, Kenneth’s brother, came up with a dastardly scheme. He rounded up every woman and child related in any way to any of the men on MacLeod’s island. He ferried them to a rock that could clearly be seen from Berrisay and announced that there they would stay until the incoming tide swept them away, unless MacLeod gave up his stronghold. Neil immediately complied, but got away himself to his kinsman, Roderick MacLeod of Harris. Roderick persuaded him to go to Edinburgh to seek a pardon. On entering the city Neil was seized and promptly executed. The last of the Highland rebels was gone.