Daisy made herself a mug of sugary tea then went outside in her coat and scarf to watch the dawn come up. A great seesaw of light balanced on the fulcrum of Black Hill, the sun rising on one end, the other end sweeping down the flank of Offa’s Dyke and switching the colors on as it went. The beauty kept slipping though her fingers. The world was so far away and the mind kept saying, Me, me, me. Petty worries rose and nagged, Benjy so distant, Mum angry with her all the time, the horrible graffiti in the changing rooms at school. But the valley … wasn’t this amazing? Look, you had to say to yourself, Look.

The truth was that she hadn’t been able to sleep. She’d tried reading Dracula but what seemed ridiculous in the daylight seemed like documentary before dawn. She felt so lost. You changed at sixteen, everyone said, and changing was hard. But this wasn’t normal, it came out of the blue, the unshakable conviction that whilst she looked like a human being and acted like a human being there was nothing inside, just slime and circuitry.

Eighteen months ago she found herself talking to Wendy Rogan, the science TA from Year 12. She can’t remember why. Providence perhaps. Wendy suggested a coffee after school over which she listened in a way that no one else had, not friends, not Mum, not Dad. The following weekend she was having supper in Wendy’s flat when Wendy suggested putting a video on. Daisy thought for several horrified seconds that it was going to be something pornographic, so when it turned out to be a promotional video for the Alpha Course she was initially relieved. A footballer scoring a goal, a model sashaying down the catwalk, a mountaineer climbing a cliff face, each of them turning to the camera and saying, Is there more to life than this? All camera sparkle and soft rock. She felt ambushed and soiled.

A week later she remembered why the mountaineer seemed familiar. He was Bear Grylls, the guy Alex loved, who climbed Everest and ate maggots and drank his own urine on television. She googled him and found herself watching, with a sickly mix of fascination and disgust, a video on YouTube in which he was stuck on a tropical island. When you get the chance to be saved, you have to take it. He swung on vines and swam across a bay and built a fire on the beach and signaled to a helicopter using the silver cross on the front of his Bible. It was laughable. But she was crying.

The valley almost full of light now, dew drying, everything washed in our absence. Melissa hated her. There was a kind of reassurance in that. Nothing to lose. No chance of feeling pleased with herself.

Be patient, David had said. The spirit will come. And there was a warmth in that room that she felt nowhere else, being lifted by those soaring voices, but the spirit hadn’t come, only that constant sniping voice. I’m more intelligent than these people. Which was what it meant to be tested, of course, the pressure always at your weakest point. Faith was a belief in the impossible. Of course it looked ridiculous from the outside. Jesus loves you, bitch. Scratched into the metal of her locker door so it couldn’t be washed off.

Suddenly there was a fox. Real orange, not the dirty brown of urban foxes, trotting through the gate, cocksure and proprietorial, like the ghost of a previous owner. Two different times were flowing though the garden. The fox stopped. Had it seen her? Had it smelt her? She didn’t breathe. The gap closed between herself and the world. She was the grass, she was the sunlight, she was the fox. Then she wondered if it was some kind of sign and the spell broke and the fox trotted off round the far side of the house and she was shivering.

Dominic stands under the shower, eyes closed, water pouring onto the crown of his head. Hot water. How amazing to be alive this late in human history. Miners in their tins baths, a kettle on the coals, Queen Elizabeth I taking three baths a year. But showers were never quite hot enough or strong enough on holiday, were they. That crappy plastic box. Down the corridor Benjy unlocks the mini-kit on the second Captain Brickbeard level and gets the wizard, while Melissa rises through that turbulent region of half sleep, part of her still at primary school, everything in slo-mo, a tiger padding slowly between the desks. Beams creak and pipes rattle as the house comes to life. A scurry in the roof space, the same dog far off. Alex pees noisily. The whir of an electric toothbrush. A cockerel. Daisy pours a small portion of Marks & Spencer’s Deliciously Nutty Crunch into a bowl.

Alex squatted on the flagstones by the front door to lace his trainers then stretched his hamstrings on the ivy-covered sill. The faintest smell of manure on the bright damp air. He set his watch then jogged along the track to the main road, stones crunching and slipping under his trainers. He loved wild places. He felt at home among lakes and mountains in a way he never did at home or school. Every other weekend he and Jamie would pile into Jamie’s brother’s Transit, bikes on the back, canoes on top, and Josh would drive them to the South Downs, Pembrokeshire, Snowdonia. Put up the tent in darkness and wake in that igloo glow. He climbed the stile and began the long haul to Red Darren, his mind shrinking with the effort and the altitude, this precious trick he had learnt, doubts and worries falling away at four, five, six miles, the fretting self reduced to almost nothing, only the body working like an engine.

Dominic and Daisy asked him about it sometimes and assumed his inability to explain was evidence of an inability to feel, but on Llyn Gwynant, on Nine Barrow Down, he experienced a kind of swelling contentment for which they yearned but never quite attained, and the fact that Alex couldn’t explain it, the fact that it was beyond words, was part of the secret.

Because you’ll burn yourself. Angela handed him two eggs. Crack these into the bowl.

What would happen if you and Dad died at the same time?

What would you like to happen? She scraped mushrooms into the pan.

I’d like to go and live with Pavel.

I’d have to check that with Pavel’s mum.

But what will happen to my toys?

She handed him a fork. You’d take them with you. She thought how small Pavel’s house was. Now add some milk and whisk it.

What about the television?

Hasn’t Pavel already got a television?

But what about our television? He was on the verge of tears.

You can have the television.

I’ve changed my mind. I want to go and live with Daisy. Something broke inside him and he was choking back the sobs.

She turned the gas down and wrapped him in her arms.

Benjamin was crying and Richard didn’t want to intrude so he poured a mug of coffee from the cafetière and walked outside where he found Alex doing press-ups on the lawn, proper press-ups, knees and back rigid, locking his elbows, touching the grass with his nose, a great eagle of sweat on his back. Deltoids, teres major, rotator cuff. He still thought of himself as a sportsman, cross-country at school, the four hundred meter at college, but in the last year he’d done nothing more than play a few games of squash with Gerhardt and cycle to work for a fortnight after the car was stolen. Alex stood up. Wondering if I should have a go myself.

Alex put a foot on the bench to unlace his trainer. It’s a big hill.

Daisy had very nearly done it with her friend Jack. She was never quite sure whether they were going out or not. He had three earrings and a pet snake and some invisible barrier that only Daisy was allowed to cross. They’d drunk two large glasses of some poisonous green liqueur his dad had bought in Italy. He put a hand under the hem of her knickers and she was suddenly aware of how angular he was, all bones and corners, and she was going to let him do it because she couldn’t think of an alternative, because this was the door everyone had to pass through. But with this thought came a scrabbling panic. She didn’t want to go through that door, she didn’t want to be like everyone else and she was having real trouble breathing. She pushed him away, and he seemed relieved mostly, but the near miss had scared them both, so they finished the bottle and the embarrassment was obscured by the memory of a hangover so bad that its retelling became a party piece. For six months they were best friends, then Daisy joined the church and he called her a fucking traitor and vanished from her life.

Alex wasn’t trying to put Richard down. It was a stab at friendliness he failed to pitch quite right. He had always rather admired his uncle and felt that Mum’s complaints were unjustified. Or perhaps admiration was the wrong word, more a kind of genetic bond. He recognized nothing of himself in Mum and Dad, her distractedness, the lack of care she took in herself, his father sitting around the house feeling sorry for himself, doing the cleaning and the shopping and Benjy’s school pickups like it was the most natural thing in the world. When friends visited he felt embarrassed by the air of defeat which hung around him and part of the attraction of mountains and lakes was their distance from both of his parents. But the way Richard carried himself, his air of efficiency and self-possession …

Why did you do that last night? asked Angela.

Do what?

You know exactly what I’m talking about. Saying grace. Making everyone feel uncomfortable.

I think we all should be more grateful for the things we have.

I think we should also be more considerate of other people’s feelings.

Oh, like you’re considerate of my feelings?

Don’t answer me back.

So, what? Just be quiet and do what you say?

You were showing off, and you were patronizing people. I don’t care what you believe in private …

That’s rubbish. You hate what I believe in private.

I don’t care what you believe in private but I don’t think you should force it down other people’s throats.

You’re just jealous because I’m happy.

I’m not jealous, Daisy. And you’re not happy.

Well, maybe you’re not the expert when it comes to what I’m actually feeling.

We’ll buy some secondhand books, said Richard. Get some lunch. Stop for a walk on the way back.

That sounds like the most excellent fun, said Melissa.

Then it’s your lucky day. He remained poker-faced. We can only fit seven in the car.

Good.

Will you be all right on your own? asked Louisa.

Melissa flopped her head to one side and rolled her eyes.

Can we walk up Lord Hereford’s Knob? asked Benjy.

He’ll stop finding it funny eventually.

I’ll duck out, too, said Dominic. If that’s OK.

Angela briefly wondered if he had arranged some kind of liaison with Melissa and came close to making a joke about it before realizing how tasteless and bizarre it would have been.

Melissa was coming up the stairs when Alex emerged from the bathroom, a sky-blue towel around his waist. Post-exercise fatigue. He made her think of a tiger, that slinky muscular shamble. There was a V of blond hairs on the small of his back. She wanted to touch him. The feeling scared her, the way it rose up with no warning, the body’s hunger. Because she loved the game, the tension in the air, but she found the act itself vaguely disgusting, André’s eyes rolling back like he was having a seizure, the greasy condom on the carpet like a piece of mouse intestine. Alex turned and looked at her. She smiled. Hello, sailor. Then turned away.

Dominic sat beside Angela on the bench. There was a scattering of crumbs on the lawn, a couple of sparrows picking at them, and another bird he didn’t recognize. This’ll be good for us, I think. Being here.

It’s a lovely place.

That’s not what I meant.

I know.

He remembered a time when they had really talked, sitting by the river, lying in that tiny bedroom naked after making love, faded psychedelic wallpaper and the Billie Holiday poster. Both eager to know more about this other life of which they’d become a part. But now? They weren’t even friends anymore, just co-parents. He wanted to tell her about Amy, to relieve the pressure in his chest, because he was scared, because he had begun to notice the frayed curtains and the smell of cigarettes in Amy’s house and the need in her voice. He had assumed at first that the whole thing was no more than a distraction from lives lived elsewhere, but this wasn’t a distraction for her, was it. This was her life, this dimly lit bedroom in the middle of the afternoon, and the secret door was in truth the entrance to a darker dirtier world from which he wouldn’t be able to return without paying a considerable price. But was it really so bad to have looked for affection elsewhere? They had both been unfaithful in their way. To have and to hold, to love and to cherish. When had they last done these things? He wouldn’t tell Angela, would he. He would live with it until the discomfort faded and lying became normal.

Poor Benjy. She examined the inside of her mug. He was talking about us dying. You know, who would get all the stuff in the house.

He seems to like it here, though. Because this was what they did. They acted like a real family. Perhaps it was what most people did. How are you and your brother bonding?

He remembers everything. She threw the dregs of her coffee into the grass. The birds flew away. It scares me. Makes me wonder if I’m losing my mind. Like Mum.

Who’s the prime minister?

I’m being serious … He could be making it all up for all I know.

Don’t we always make them up, our childhood memories? His own mother had slept with another man, the dapper little dentist with the soft-top Mini. Or was it just a spiteful rumor?

They sat for several minutes looking at the view. They had this at least, the ability to sit beside one another in silence.

I have difficulty believing that Richard and I are actually related. The birds were reconvening around the crumbs.

Maybe you were adopted. That might solve a problem or two.

Another of his jokeless punch lines. But Richard was calling, Wagons roll.

Countryside like an advert on TV, for antiperspirant, for butter, for broadband, a place to make us feel good inside, where everything is slower and more noble, cows and hayricks and honest labor. Somewhere out there, hard by a stand of beech, commanding an enviable prospect of the valley, the house where the book will be written and the marriage mended and the children will build dens and the rain when it comes is good honest rain. How strange this yearning for being elsewhere doing nothing. The gift of princes once, its sweet poison spreading. Lady Furlough surveying the desert of the deer park, the monsters coiling in the ornamental lake, that terrible weight of hours, laudanum and cross-stitch. What every child knows and every adult forgets, the glacial movement of the watched clock, pluperfects turning slowly into cosines turning slowly into the feeding of the five thousand. School holidays of which we remember only mending bikes and Gary Holler killing the frog, the featureless hours between gone forever.

And now you must do nothing for a week and enjoy it. Days of rest long past the point when we’re rested, holidays without the holy, pilgrimage become mere travel, the destination handed to us on a plate, the idleness of the empire in its final days.

Melissa had been sitting at the dining-room table reading when Dominic walked through and said he was going for a walk. The door banged and she became aware of how quiet the house was. She stuck her iPod on. Monkey Business, Black Eyed Peas, but the inability to hear someone approaching from behind made her feel vulnerable so she took the earphones out again. She stepped into the garden, wanting the minimal reassurance of Dominic’s shrinking silhouette, but he was gone and the valley was empty. She went back into the living room and rifled through the stack of DVDs. Monsters, Inc., Ice Age 2, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. There was a Simpsons case but it contained a PlayStation disc for Star Wars Battlefront.

A whir and clang behind her. She span round. The grandfather clock chimed again. Fuck. She needed to talk to a normal human being. Megan, Cally, Henry, anyone. She grabbed her phone and headed for the hills.

He’d been looking forward to it for the last couple of weeks. A town of books. All this learning gathered in and offered up. Trawling, browsing, leafing. But now that he was standing in the bowels of the Cinema Bookshop … That smell. What was it, precisely? Glue? Paper? The spores of some bibliophile lichen? Catacombs of yellowing paper. Every book unwanted, sold for pennies or carted from the houses of the dead. Battersea Books Home. The authors earned nothing from the transaction. Salaries less than binmen, he’d read somewhere. He thought about their lives. No colleagues, no timetable, no security, the constant lure of daytime television. The formlessness of it all made him feel slightly ill, going to work in their dressing gowns. So much risk and so little adventure.

He laid his hand on the bumpy wall of frayed spines and brittle slipcovers. His mother had arranged them according to their height, as a kind of subsidiary furniture. Airport novels and Hollywood biographies. He wished he were better at embracing the chaos, loosening up a little. But the journey was always a circle. You thought you were on the other side of the world then you turned a corner and found yourself in the kitchen with the green melamine bowls and the clown calendar. His neatness, his love of order, the need to keep himself constantly busy, these things weren’t a measure of the distance he’d put between them, these were the things they had in common.

The Golden Ocean. Anglo-Saxon Attitudes. The House of Sixty Fathers. They Call Me Carpenter. Tom Swift and His Electric Locomotive. The Velveteen Rabbit. The Chessmen of Mars. The Eagle of the Ninth. Tarzan and the Forbidden City. The Man Who Could Not Shudder. Typewriter in the Sky. The Naughtiest Girl in the School. Black Hunting Whip. The Secret of the Wooden Lady. Five Go to Mystery Moor. The Drowning Pool. The Courage of Sarah Noble. My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Bonjour Tristesse. The Sky Is Falling. The Sound of Waves.

Holy shit. There was a naked woman tied up. Then another naked woman tied up. Then a naked woman tied up and hanging from the ceiling. Then a naked tattooed woman with her arse in the air and a dildo sitting on a record player in the background. Then a naked woman with an Egyptian hairstyle on an old-fashioned hospital bed tied up with rubber tubing that actually went into her cunt. And it was, like, actual art that you were allowed to look at. Or was it? Alex flipped the cover shut. Nobuyoshi Araki. Phaidon. Eighty-five pounds. So it was art. Holy shit. You could have it on a coffee table. He imagined being the photographer. Actually being there in the room. There was a close-up of a big veiny penis in black and white which was gross, then two naked women on a bed.

Excuse me.

There were other human beings in the room. The man squeezed past and disappeared into Architecture. Alex stared at the photograph of the two women. He wanted to buy the book. He wanted to steal the book. He wanted to stay here forever. He had to put it down. He couldn’t put it down.

Dominic was thinking of the opening of the second Two-Part Invention, that little canon. When the work stopped he couldn’t bear to listen to music. Sentimental songs were the worst, “The Power of Love,” “Wonderful Tonight” … He had to leave shops sometimes. Just like Coward said. Extraordinary how potent … etc. After a couple of months he started listening to Steve Reich and suddenly saw the point of those cool, evolving lines. Music for Eighteen Musicians, Electric Guitar Phase. Moving gingerly on to Bach. Another kind of coolness. He ran though the fingering of the Two-Part Invention in his head. Who was the guy on that classical-music quiz show when he was a kid? He played a dummy keyboard and you had to guess the piece from the thumping. Joseph Cooper. That was it. Face the Music.

He looked across the valley and heard The Lark Ascending in his mind’s ear, that skirling violin, four semiquavers then up and up, pentatonic scale, no audible root, no bar lines even … Melissa. Jesus. Was that Melissa? He started to jog down through the bracken. What in God’s name was she doing? Vomiting? He tripped and fell and got up again. She was on all fours. He slowed, panting. Melissa? He touched her shoulder and she sprang up and screamed, waving her hands like a frightened woman in silent film. Whoa, sorry. I didn’t mean …

It’s … It’s … She stroked the air in front of her. Angela’s husband. She’d forgotten where she was. She felt naked. Was he going to attack her?

Are you all right?

She mustn’t cry. She held out her mobile. It refused to explain the situation. I couldn’t get any signal.

Have you hurt yourself?

No, I haven’t fucking hurt myself. Deep breath.

You were trying to ring someone.

I’ve got to … She turned and walked away and her knees buckled and she tried very hard to make it look like she was sitting down on purpose.

He came over and sat beside her. They said nothing. It was uncomfortable, then it was comfortable, then it was uncomfortable. So I guess you’re not having a fun time.

She started crying. Shit. She wiped her eyes.

You want to talk about it?

No, I do not want to talk about it. Unsurprisingly.

He picked two daisies and started making a chain. I had a stepfather. I still have a stepfather.

What the hell was he talking about?

He was a really nice guy, which only made me hate him more, of course.

Yeh, well, thanks for the advice. She took a packet of Silk Cut from her jacket pocket.

One going spare?

She’d meant to piss him off but things were going a bit off-piste. His cupped hand touched her hand. The scratch and pop of the lighter. Was he going to try and feel her up? She imagined hanging on to the story like a fat check she could spend whenever she wanted.

Ooh. He blew a rubbish smoke ring. Haven’t had one of these in a while.

A sheep trotted past, bleating.

Actually, Richard’s all right. He kind of makes Mum happy, which is good. But it was a lie. She hated him for the same reasons Dominic had hated his stepfather.

They finished their cigarettes. Then Dominic turned and stared at her. She wondered if he was going to put a hand on her breast. Be nicer to Daisy, OK?

Which caught her totally on the hop.

You’ll look back and realize you’re not that different.

She laughed. We are so different. He held her eye and didn’t laugh. She’d lost her bearings now. The fear was coming back. She got to her feet and threw her cigarette stub into the long grass. I need to make a phone call.

Don’t walk over a precipice.

Was he being, like, metaphorical, or was there actually a precipice?

He watched her stumble up the hill. Town shoes. He imagined getting points for the way he’d handled the conversation. Six out of ten? He’d definitely got the better of her. Seven? The sheep bleated again. He felt a little nauseous. The cigarette, probably.

Benjy was doing a kind of boneless gymnastics on the leather armchair at the side of the shop.

Look at this encyclopedia. Daisy heaved him aside and sat down. It’s from 1938.

His eyes were fixed on the Nintendo.

Back before computers, when they thought there might be people on Mars.

He didn’t look up. I want to find the Encyclopedia of Torturing Barbie.

She turned the page. And what is this thing, she read, which the savage coaxes into being by rubbing one stick against another, and the civilized man conjures in a moment by striking a match? His breath wasn’t good. Had anyone made him brush his teeth this morning?

Louisa appeared suddenly. Benjy … Daisy … She had peeled herself away from Richard and set off in search of a sunny book-free location, but there was something cozy about the two of them in the chair. What have you got there?

Pictorial Knowledge, Volume 5. Daisy handed it to her.

Woven brick-red cover, the title indented and beneath it an oil lamp radiating beams of wisdom. She glanced at the contents page. “How Steam and Petrol Work for Man.” “A Children’s Guide to Good Manners.” “Folding Model.” She was suddenly back in her grandparents’ house, chicken-wire window in the larder, walnut whips and buttered white bread with fish and chips, the stilts Granddad made her from an old doorframe.

Daisy shifted a little to get more comfortable. Louisa had sat herself on the arm of the chair, Daisy sandwiched between her and Benjy. Louisa’s leg was very close. Red cords tight around her thighs. The smell of cocoa butter.

Louisa turned a page. Arch, suspension, cantilever, girder. How strange that she should be reminded of them here, of all places, when they didn’t have a single book in the house. The fear of getting above yourself. She closed the book and ran her hand gently down the spine. You thought it was all gone, the house demolished, the furniture sold, photos eaten away by mildew and damp. Then you opened a tin of sardines with that little metal key.

He sat on the steps of the town clock, the bag from Richard Booth angled against his calf (Stalingrad by Antony Beevor, The Odyssey translated by John Hannah, Fighting Fit: The Complete SAS Fitness Training Handbook). There was a trailer containing two sheep, and three local teenagers standing round a scooter, smoking. The Sharne case was nagging at him again. Breathe in, two, three … Breathe out, two, three … One of the boys revved the scooter and his concentration broke. How restless the mind was. He should run, like Alex, clear it with activity instead of willpower. Breathe in … He noticed an attractive woman going into The Granary and heard that tiny sexual alarm sounding in his head. Oh, but it was Louisa. Then she was gone. How disorienting to see her as other men saw her. He remembered meeting her ex-husband that first time, when Craig came round to fit a new pump in the boiler. Absurdly hairy, as if he was wearing a black mohair vest under his T-shirt. Louisa tells me you’re a doctor. A muscular handshake that went on for just a little too long.

Consultant. Neuroradiology.

Eventually he came to understand that it was a kind of Kryptonite, the degrees, the books, the music, though he remembered Louisa shaking her head and laughing and saying, He wanted it all the time, and he was never quite able to shake that picture.

There wasn’t a precipice, just a huge hill from which you could see Russia probably. An old couple walked past dressed like Boy Scouts. Then her phone made contact with civilization and a string of texts pinged in, one from Dad in France followed by a stack of messages saying ring me and got 2 talk 2 u and need to talk urgent as if an actual war had broken out. She called Cally who didn’t even say hullo, just, Michelle tried to kill herself.

How?

Sleeping pills. She told her mum we were bullying her.

Fucking cow.

Thing is, her mum went to see Avison, so now it’s official.

Well, it wasn’t me who sent that picture to everyone.

Don’t fucking dump me in it, said Cally. You took the photo.

Stop blaming me, all right? We’ve got to sort this out. Christ. Two weeks in a sleeping bag in a half-renovated French farmhouse with Dad didn’t seem such a bad idea now. She let it all sink in. Michelle being a slag as per usual. Michelle playing the victim as per usual. She should have seen this coming a long way back. Who else did you send it to?

Not that many people.

Just tell me, OK?

Jake, Donny, KC …

Fucking great. They’d save it, wouldn’t they, so they could stab her in the back. All those idiotic little vendettas. If she was only there, in person, to grab the phones out of their stupid hands.

I didn’t think I’d be so upset when she died. Angela took a final forkful of Tibetan roast. Benjy was sitting next to her reading a tattered secondhand encyclopedia. She brushed the crumbs from his hair.

Ghastly way to go, said Richard. He’d arranged his cutlery at half-past six. Your mind dying, your body left behind for other people to look after.

Other people? Meaning her.

God forbid that I go like that. He poured the last of his tea through the metal strainer. Over his shoulder a gaggle of nut-brown cyclists gathered at the counter, little black shoes clacking on the stone floor. Give me a massive cardiac arrest.

Hang on, said Angela. Hang on. Why was she doing this? I visited her every week for five years.

I’m not sure what you’re trying to say. He could hear the resentment in her voice but was genuinely confused. Surely the gift of the holiday itself had removed any residual bad feelings.

I know you paid for her to be in Acorn House, said Angela. And maybe that was more important than anything else. I’m grateful, I am, but … She was walking on cracked ice. Every week for five years. What good had it done, though? Her mother didn’t recognize her at the end.

I know, said Richard, tonelessly.

And the person she really wanted was you. She could see the disbelief in his face. He’d expected this to be easy, hadn’t he. Rebuilding the family now the troublesome parent had been removed. Bruises and broken bones. She felt a childish desire to make it as difficult as she could. And you came, what? Five times? Six? She knew the exact number but she wasn’t going to admit to having kept score.

Richard was drawing little shapes on the tabletop with his index finger. She wondered if he was working out his reply on imaginary notepaper.

She’s dead, Angela. We can’t change anything now. Perhaps we should just leave it alone.

Benjy turned a page, oblivious to their conversation. Angela glanced over. The Romance of the Iron Road. A picture of the Flying Scotsman. I just wanted to hear you say thank you. There. It was out.

He laughed. Quiet and wry, but actual laughter.

Richard …? She felt as if she were talking to a child who had made some dreadful faux pas.

I was thirteen when she started drinking.

And I was fourteen.

But you left.

What? She really did have no idea what he was talking about.

When you moved in with Juliette.

The idea was so crazy that she wondered for the first time if he had some less pleasant motive for bringing them on holiday. I never left. I never moved in with Juliette.

OK, maybe not moved in. He hadn’t meant to bring this up. It was like contaminated earth, if you didn’t dig there was no problem. But you spent most nights there. He didn’t want to settle scores. He simply wanted things to be neatly folded and put to sleep. For the best part of two years if I remember correctly.

That’s simply not true. The couple at the nearby table had paused to listen.

Perhaps if I’d been better at making friends I would have done the same thing. He laughed again but more warmly this time.

That’s not the point. They had to stop this right now or God alone knew where it would go. She sat back and deep-breathed. Let’s call a truce.

A truce? said Richard. Is this a war?

Maybe now is the time for cake.

Without taking his eyes off the book, Benjy said, Yes please. Can I have the chocolate one, please, with the white icing?

Motor lorries carry heavy goods long distances; motor vans deliver parcels at our doors. Motor charabancs transport tens of thousands of pleasure-seekers daily from place to place, and motor coaches make regular daily journeys between towns hundreds of miles apart. We no longer see the horse-drawn fire engine, with smoke belching from its funnel, dashing down the street.

Ariel Gel Nimbus 11. Ridiculous names they gave these things. Richard loved the smell, though, plasticky and factory-clean. He laced the left shoe up and leant round to take the right from its tissued box. He felt bruised by the conversation with Angela, less by her feelings than by his failure to predict them. It had never occurred to him that she would feel embittered. His mother had hated him for looking after her, then hated him for leaving. Five years living with an alcoholic woman and no one had thanked him. If there was such a thing as the moral high ground it was surely he who occupied it. From the corner of his eye he saw, through the shop’s front window, a rat’s nest of black downpipes emerging from the upper story of the house opposite. He rotated his body a little farther toward the rear of the shop.

How much?

Seventy-nine pounds, ninety-nine pence.

Reassuringly expensive.

The assistant seemed oblivious to his irony. But you had to have the best. Save twenty pounds now and you regretted it later. He stood up and examined himself in the mirror.

How do they feel? The young man was ginger and plump and ill-nourished with one of those increasingly popular asymmetrical fringes so that he was forced to lean his head to one side in order to see properly.

Good. They feel good. He squatted and stood up again. He remembered the day he left for Bristol, his mother yelling at him as he walked down the street with his rucksack, curtains twitching, like a scene from a cheap melodrama. Ideally he should have gone outside and run up and down but he wasn’t sure he had the confidence to carry it off. He jogged on the spot for ten seconds. I’ll take them.

Angela stayed in the car. She needed time away from Richard and she couldn’t imagine another two hundred feet improving the view. A young Indian woman was fighting an orange cagoule. A little farther away a man and two teenage boys were tinkering with an amateur rocket, three, four foot high, red nose cone, fins. The man knelt briefly beside it then stepped back and … Jesus Christ. A fizz like Velcro and the thing just vanished upward. The boys whooped and waited and it simply didn’t come down. They swiveled, scanning the distance. Carried off by the wind, no doubt, but something magical about it still, a story for later. She looked back up the hill. Her family were dots.

Was he lying about Juliette? Or had he misremembered to alleviate his guilt? If only she could retort with hard facts, bang, bang, bang, but she had never really looked back, never thought these details might need preserving.

God, she wanted something to eat. Toffee, sweets, biscuits. She opened the glove compartment and a strip of passport photos fell out. She picked them up and turned them over. Melissa smoldering, Melissa blowing a kiss, Melissa flicking her hair. They were oddly touching. She thought of all those pictures of Karen. Two years old, playing with wooden blocks on a sheepskin rug. Nine years old, in front of a rainbow-colored windbreak. Fourteen years old, in a green duffle coat at some steam fair, the word OGDENS in Victorian funhouse lettering on a green boiler behind her head. And for a few giddy seconds they were real, in a leather album on the shelf above the telly. Then the wind shook the car and she was in the world again.

Alex looked back and saw Daisy and Benjy throwing lumps of sheep shit at each other. Only the dry ones, shouted Daisy. At school he got the piss ripped for being her brother, Eddie Chan singing “Like a Virgin” forty thousand times. Nastier stuff, too, especially after the antidrug assembly, like she wanted people to hate her. He could shut most things out but not this. Was she fucked up or just being a smug twat? Should he protect her or leave her to get what she deserved? It was a puzzle and it bugged the hell out of him that he couldn’t solve it.

That went in my hair, you little …

He wondered if she might flip back sometime. Not that they’d be friends or anything. But still.

Louisa moved out of range. A teenage girl playing a little boy’s game. It didn’t quite compute. Maybe if she’d had boys, if she’d had the brood she’d once dreamed of. Though sometimes, when Melissa was really tired and Richard was out, she curled up on the sofa and lay her head on Louisa’s leg and sucked her thumb, which was what one wanted ultimately, wasn’t it, that connection.

Goal. Benjy pulled his shirt over his head and ran around in circles.

Daisy shook a wet lump off her jeans. You are so going to die.

Richard felt a hand tighten round his heart. He had never done this. He would never do this.

Daisy wrestled Benjy onto the grass. He yelled, That’s cheating, but it wasn’t a serious protest because he loved this. No one gave him piggyback rides or picked him up anymore. You could ask for hugs if you were feeling sad or you’d hurt yourself, but when it happened spontaneously it made you feel so warm inside.

Is Angela all right? Louisa was looking down the hill to the higgledy-piggledly cars.

He loved her for thinking about these things. The funeral hit her harder than I expected.

You bought some running shoes.

I saw Alex coming back this morning.

Don’t break an ankle.

Trust me, I’m a doctor.

She laughed and he remembered when he’d first said those words to her and how she’d laughed that time too. He wanted suddenly to be on holiday alone, just the two of them, making love in the middle of the day, seeing her body in sunlight through the curtains.

And Daisy and Benjy were lying on their backs. Look. You can see the sky moving. And Alex was farther up the hill, shouting, Come on.

Two crows abandoned something dead in the road as they drove past. A postbox in a wall. Ruinsford Farm. Three Oaks Farm. Upper House Farm. A crazy dog chased them for half a mile. Being in the back of the car made Alex twitchy, too far from the steering wheel, being taken somewhere by someone else. Next year he’d arrange his own holiday. Dolomites, maybe. Next year he’d start to arrange everything. Economics, history, business studies. Brighton, Leeds, Glasgow. Travel for a couple of years. Start his own business. Not ambitions, just facts about the world. You knew where you wanted to go, you worked out the route and set off. He didn’t understand why so many people made such a bloody hash of it. Then they were pulling in through the gate and Melissa was sitting reading on the low wall at the back of the house and he felt that little surge of panic, like at the beginning of a race, or when you were about to do some stupid vertical drop on the bike. But you couldn’t turn back.

He got out of the car and walked over. She was wearing tight jeans and boots and a little black jacket over a lacy Victorian dress. She didn’t acknowledge his presence until he was really close and when she turned to him her face was blank. She hooked her hair behind her ear like her mum did.

Here it comes, she thought. Because this was what she liked, this tension in the air, the way you could play someone.

What’s the book?

She flipped it over.

Good? He sat and swang his legs like a little boy.

Uh-huh. You had to say as little as possible and let the other person fill the gaps.

So. He looked down at his swinging feet. Did he look casual and relaxed? It was hard to see yourself from the outside. How do you like it here?

About one out of ten.

So what’s the one?

He wanted her to say it was him. Peace and quiet, time to think. She lifted the fizzy little glass of gin and tonic. No lemon. But needs must, right?

I bet you don’t really like peace and quiet.

He wasn’t bad at this.

I love it here. You know, the space, the view from up there.

Or from down here. She raised an eyebrow.

They were silent for a while. Now. Go for it. He reached out and put a hand on her thigh. The warmth of her skin under her jeans. They looked at the hand, like a bird they didn’t want to scare away. He turned and kissed her. She tasted so good. She put her hand on his chest but he couldn’t stop because sometimes girls pretended they didn’t want to and it was so hard to turn back. His hand was on one of her breasts. But he smelled faintly of sweat and he was pushing his tongue into her mouth and she was surprised by how strong he was. She grabbed one of his fingers and bent it back. Just fucking stop, OK?

He sat back. Sorry.

Christ.

I got carried away.

I noticed.

They sat beside each other, saying nothing. A helicopter buzzed over Black Hill like a housefly. The taste of her mouth. He still had an erection. Melissa got down off the wall. Anyway. Things to do. People to see. She walked off toward the door carrying her book and Alex had absolutely no idea what to think.

There was a random collection of Victorian engravings in the house, purchased as a job lot from the dump bin of a gallery-cum-junk shop in Gloucester. The North Gable of Whitby Abbey; a dog baiting a bear; Walter Devereux, Earl of Essex; the Brampton hunt at full pelt; a baroque faux-temple of indeterminate location; Mount Serbal from Wády Feirán …

Louisa slotted her iPhone onto the dock and pressed Play. She squeezed the handles of the tin opener and the sharp little wheel popped through the metal lid. U2. “Where the Streets Have No Name.” She poured the beans into the colander and rinsed off the gluey purple juice. There was no food processor so she used the potato masher, banging it on the rim when the holes became clogged. It made her think of her mother in the kitchen, beef dripping and hand mixers. What are you doing?

I’m selecting a snack, said Benjy. He loved standing in the golden light and the cold air that poured out of the fridge with its treasure hoard of food.

Well, if you could select quickly I would be really grateful.

He selected and shut the fridge door. That thump and tinkle. Then he was gone. The pepper grinder was empty so she took the little plastic tub off the shelf, ridges round the lid like a fat white coin. She took it off and smelled the contents. Absolutely nothing. Like house dust.

Benjy walked into the dining room, peeling back the little plastic cover then licking the yogurty patch on his trousers where it had spilt. He put the pot to one side and then folded a sheet of A4 paper into eight so that it formed a little book. He took out the pen that wrote in eight colors. It would be called A Hundred Horrible Ways to Die and it would include torture and killing but not cancer. But Mum was standing beside him. Who said you could have that yogurt, young man?

Auntie Louisa did.

Is that a lie?

Only slightly.

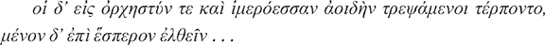

Now the suitors waited for evening to come by entertaining themselves with dances and happy songs … But Richard was falling asleep.

Now the suitors waited for evening to come by entertaining themselves with dances and happy songs … But Richard was falling asleep.

To be honest, said Angela, it’s not just the Richard thing.

Go on.

It’s Karen’s birthday on Thursday. She levered a pistachio shell open.

Wasn’t that in February?

Not the day she died. The day she was meant to be born.

What do you mean, the day she was meant to be born?

5th May. It was my due date.

You’ve never talked about this before.

She’d cracked a nail. I think I might be going a little crazy.

Sayid follows the twisted metal cable into the jungle. Marimba and harp, the sky a scattered blue jigsaw in the canopy, spiderweb glimmer at ankle height. He crouches and sees the single trip wire. High dissonant violins. He steps carefully over. The whip-slither of a rope snapping tight as a sharpened stake is fired into his thigh. He screams, his legs are yanked from under him and he’s hoisted like a pig for slaughter.

Alex fast-forwards through the beach section because he needs dramatic tension to stop himself thinking about Melissa. Over the last year he has become something of a film buff. Two, maybe three full-length features every shift at Moving Pictures, just a weather eye on the screen during the busy times. Best of all he likes TV box sets. Lost, 24, Battlestar Galactica. The consistency mostly. You enjoyed episode three? You’ll probably enjoy episode four. Less hassle all round.

Nighttime. Sayid is lying on the ground. The blur of semiconsciousness. Someone approaches wearing military fatigues. Moonlight on a jagged knife. Sayid’s eye fills the screen, then flickers, then closes.

I poured myself another glass of the Monbazillac. As I raised it to my lips something moved in the darkened hallway. Was it the white shoe? My heart hammered, the stimulus rushing through my sensory cortex and hypothalamus to the brain stem, flooding my body with adrenaline. I walked over and found that my coat had slipped off its hook. I breathed deeply trying to slow my racing pulse. Fight or flight, the loyal guard dog that has sat by our side for a million years, alerting us to every sign of danger. But how could one fight an imaginary threat? How could one flee the pictures in one’s head? As Hecht had written in his article for Nature, we had tamed the outside world but not the weapons we possessed for dealing with it …

Melissa put the soggy paperback facedown on the edge of the bath, the pages turning slowly into a great damp ruff. Avison would ask Michelle how they’d been bullying her. What was she going to say? She couldn’t show him the picture, could she. But if the police were involved they’d look at everything. Shit. She’d always managed to tread the line. You could smoke as long as you did Midsummer Night’s Dream. You could skip the odd class as long as you got the grades. But if she got expelled Dad would go fucking ballistic. Goodbye allowance for starters. She didn’t even want to think what shitty school she’d end up going to.

There was a print of a robin above the toilet and an air freshener in a crappy pink holster thing on the side of the cistern. Alex groping her. God, she hated this place.

Benjy had a special dispensation to play his Nintendo at the table because he was bored of grown-up talk. Daisy tried to prize him away by asking him about school but he wanted to talk about his ongoing fantasy in which Mrs. Wallis killed and ate children in her class, which Daisy found tiresome and distasteful so she admitted defeat. She tried talking to Alex but he kept stealing glances at Melissa who was studiously ignoring him. She felt oddly protective and wanted to apologize for her brother’s behavior though she was pretty sure it was Alex who’d come off worst. She stared at her willow-patterned plate. She must have seen the picture a thousand times but she’d never really looked at it, the ship, the temple garden, the figures on the bridge. What was happening?

Mum and Dad were sitting at opposite corners of the table. Why didn’t they love each other? It was easier being here with Louisa and Richard and Melissa who acted as a kind of padding. At home the temperature was always a little cooler when the two of them were together. She’d been at Bella’s house one day when she was eleven. Bella’s father slipped an arm round her mum’s waist and kissed her for way too long. Daisy was horrified at first, then she realized and it made her sad.

It’s good for Richard being here. Louisa poured herself another glass. Stop him worrying about things.

I can’t imagine Richard worrying, said Dominic. He could feel something stuck between his front teeth. Not like the rest of us worry.

Oh, there’s this case at work, said Louisa. Some legal thing. Had she said too much?

What kind of legal thing?

We’re going to have the stage near the trees at the edge of the playing field, said Melissa. She closed her eyes in order to see the plan more clearly. The sun will be out at the beginning of the play, which is when we’re in the city, and it’ll set during the play which is when everything moves to the wild forest. Cool, no?

That sounds really interesting, said Angela. Melissa was just a child, wasn’t she. Queen of the castle and dirty rascals. So tell me about being vegetarian.

I just think it’s ridiculous eating animals.

No, said Angela. Give me a reasoned argument. Imagine you’re trying to convert me.

Well … Melissa paused and gathered herself.

It was so easy. Get them on their own and treat them like adults. Except you couldn’t do it with your own family, could you. You crossed your own doorstep and took off the cape and you were Clark Kent again.

So, what happens if you’re not cleared? asked Dominic.

I think that’s highly unlikely.

But hypothetically. Dominic could see that he was making Richard uncomfortable but he was slightly drunk and the opportunities for enjoying this kind of advantage were few and far between.

I suppose ultimately, if one had been grossly negligent, one could be struck off. Richard could think of no way of ending the conversation without giving the impression that he was avoiding the subject.

I suppose most of these cases are settled out of court. Dominic mopped up the last of the tomato sauce with a folded piece of bread.

I would much rather be publicly exonerated. Sadly, it will be the word of an honest man against that of a liar and a hypocrite.

Louisa reappeared with an apple tart in one hand and a tub of vanilla ice cream in the other. Richard got slowly to his feet. Let me fetch the bowls.

Angela placed a stack of dirty plates in front of Benjy because she was determined that at least one of her sons would leave home with a few domestic skills. Put these in the dishwasher. Carefully and one at a time, OK?

I’ll do the greasy stuff in this sink, said Daisy. You can do the glasses in that one.

Let’s play the story game, said Benjy.

Concentrate, said Angela. If you drop any it’ll be coming out of your pocket money.

Which story game? said Daisy.

The one where you say a word and I say a word then Mum says a word and we have to make up a silly story.

So long as it doesn’t have poo in it, all right?

But I like stories with poo in.

We know, said Angela, patting his head, but that’s a personal problem and I really do think you should keep it to yourself.

Go on then.

Once …

There …

Was …

Tangerines …

You can’t have “was tangerines.”

Why not?

Because it’s grammatically incorrect.

OK. Once there was a …

Grapefruit …

But I wanted “tangerine.”

It’s not your go. You have to wait till your next turn and then add something ridiculous. So … Once there was a grapefruit …

Whose …

Trousers …

Were …

Made …

By …

A …

Squirrel …

Who …

Lived …

In …

A …

Handbag …

Made …

Of …

Poo …

Benjy …

Melissa popped open the second Rotring tin, took one of the joints out and smelled it. Resin. Like the stuff you used on violin bows in its little velvet handkerchief. It was a kind of amber, wasn’t it. Rebuilding dinosaurs from mosquito blood. God, the T rex should have eaten those whiny kids. She got stoned with Mum once and Mum told her how Dad tied her to the bed with the dressing-gown cord sometimes, which was really funny at the time and so deeply not funny the following morning. And when Megan tried it for the first time … This is totally fucking freaking me out, all snot and mascara, so Melissa spent the whole night feeding her mugs of black coffee and letting her win at Pictionary. But Melissa liked being stoned, the way everything backed off and time went rubbery.

She checked the landing was clear. Downstairs the clatter of plates. There was a door at the end leading to a flight of stone steps into the garden. She opened the Yale lock and left it on the latch and stepped out into the dark. The moon was almost full, ragged clouds were racing high up, but the air in the valley was completely still. The dog was still barking. God, she was going to be hearing it in her sleep for the next month. Faint voices from the yellow windows, everyone drinking coffee and talking bollocks about schools and house prices. She sat on the rusted lawn roller just inside the woodshed and took the joint out of her pocket. She span the rough little wheel of the lighter. Sparks like a tiny blue thornbush in her hands.

Once upon a time there was a beautiful woman, Koong-se, who fell in love with her father’s clerk, Chang. But her father had promised Koong-se to a wealthy duke, so he sacked Chang and built a high wall around the palace to keep the lovers apart. The duke arrived bearing a casket of jewels and the wedding was set for the day on which the willow blossom fell. The day before the wedding Chang slipped into the palace disguised as a servant and the two lovers ran away with the casket of jewels. Koong-se’s father saw them and chased them over the bridge brandishing a whip. Luckily they managed to escape by stealing the duke’s ship and sailing it to a deserted island where they lived happily together.

Years later, however, Koong-se’s father discovered the whereabouts of this deserted island and dispatched soldiers who caught the two lovers and killed them. The gods saw this and took pity on Koong-se and Chang and transformed them into the pair of doves who hover permanently in the sky above the water and the willow trees and the temple garden.

Society has become far too materialistic, said Daisy. We’ve lost sight of the important things.

For an intelligent young woman, said Richard, you really are incredibly naïve.

Richard … said Louisa.

I am not naïve, said Daisy. She didn’t want to be protected, she wanted to win the argument on Richard’s terms.

Alex stretched out his legs and knitted his fingers together as if he was settling down to watch a good film.

You want to live in the Middle Ages? said Richard. He knew the conversation with Dominic had upset him and that he was taking it out on Daisy, but he disliked being lectured, especially by someone who thought the rest of them would burn in hell. You want kids to die of cholera and dysentery? You want your teeth to fall out? No radio, no television, no central heating?

Richard … said Louisa, more insistently this time.

That’s not the point, said Daisy. She hadn’t drunk alcohol for eight months whereas Richard had downed a bottle of wine. It should have given her an advantage but it seemed to work the other way round.

It is precisely the point, said Richard. You need money. You need big business. You need competition. You need people to want more, to want better, to want faster. Materialism is not some evil tumor in the body of society. Materialism is the reason why most of the people in this room are actually alive.

Angela had rather enjoyed it at first, these two opinionated people locking horns, but something more was at stake now and she could hear the malice in Richard’s voice. She remembered their conversation in The Granary. She was beginning to realize that he was not a very nice man.

Just because you’re more intelligent, said Daisy, you think that makes you right.

One-nil, said Alex, who had drunk several beers himself. Straight through the keeper’s legs.

Richard didn’t take his eyes off Daisy. And you’ve got some growing up to do, young lady.

I think that’s probably enough, Louisa said quietly to Richard, as if he were a small boy, and Angela thought, Yes, that’s exactly what he is.

You all right? asked Dominic.

I’m OK. Benjy was sitting on the edge of the bath in his Tarzan pants and his skateboard top. I’m just a bit sad.

You’re tired, that’s what you are. I’ll do your teeth for you.

Ouch.

Well, keep your mouth open.

There were bottles and boxes arranged along the windowsill like a little alien city. Moisturizer, dental floss, an electric toothbrush, Cyberman Bubble Bath. He slalomed between them in his space scooter.

Spit and swill.

What’s a tampon?

You don’t want to know.

Are they like condoms?

Seriously, you do not want to know.

Is it a sex thing?

No, it’s a lady thing.

Dominic shepherded him to the bedroom. Benjy got under the duvet and fidgeted himself into a comfortable position while Dominic picked up The Gate Between Worlds from the carpet. So … They took off their boots.

“But I’ll get cold.”

“You can be cold or you can be dead,” said Mellor. “Now take it off and leave it on the ground next to the boots.”

Joseph shivered. The dogs were getting louder. “Are we going to swim?”

“We walk through the shallows,” said Mellor, “over to the rocks. The dogs will lose our scent and the Smoke Men will think we’ve drowned or swum to the other side. Quickly. Into the water.”

Did I miss something? Dominic paused in the doorway.

Daisy and Richard had an argument about religion, said Angela.

He was showing off, said Louisa. The way men do.

I resent that, said Alex.

You’ll be exactly the same, said Louisa. It sounded almost flirtatious.

Dominic touched Daisy’s shoulder. You OK?

I’m fine. Though in truth she felt a little unsteady, like when you sliced a finger chopping vegetables.

Benjy all right? asked Angela.

Out like the proverbial. He surveyed the room. Where’s Richard?

He thought, for a moment, that it was a minor hallucination, an orange firefly in the dark of the woodshed that vanished almost as soon as he saw it. He froze. That breathless adrenaline clarity. Someone was in there. The moonlight dimmed and brightened with the passage of clouds. A wisp of smoke trailed from the gable. He did a rapid calculation. Melissa. He should have let it go. Don’t ask, don’t tell. But his control over various things had slipped during the day and he disliked the idea of backing down. He walked round to the open side of the woodshed. He expected to see where she was sitting but the interior was filled with a sheer and impenetrable darkness. Melissa?

Hello, Richard. Her voice made him jump. Fancy meeting you here. Disembodied completely.

The orange firefly appeared. You’re smoking.

No shit, Sherlock.

Smoking is not good for you. He should have planned this better. But the smell … What’s in that cigarette?

She blew smoke toward him and it bloomed into the moonlight. Want a drag?

Put it out.

Go on. That knowing voice, sexual almost. Help you relax.

I said …

Richard, said Melissa, with amused patience. The effect of the marijuana, perhaps. You are not in charge of me.

It was obvious to both of them that he had already lost both the battle and any means of honorable retreat. Let’s see what your mother says about this. He turned away.

Oh, come on, said Melissa, she’s smoked enough of the stuff.

I sincerely doubt that.

Melissa laughed. Jesus, Richard, there are so many things you do not know about my mother.

He wanted to step into the dark and slap her face. The thought scared him. He moved slowly backward as if he were carrying a tray stacked with glasses. We shall talk about this later.

They have two orchestras, said Louisa. Swimming pool, climbing wall. But her friends live miles away. She needs a chauffeur, basically.

The front door thumped shut and Richard walked into the room. He looked punch-drunk. Melissa is smoking marijuana in the garden and there is absolutely nothing I can do about it, apparently.

Louisa closed her eyes and breathed deeply. Angela and Dominic looked at one another. Were they allowed to find this funny?

So, anyway … He had expected a bigger reaction. Then he saw Daisy and realized how dishonorably he had treated her and how this mattered more. He deflated visibly. Angela poured a coffee from the cafetière and slid it toward the space on the bench he had vacated ten minutes earlier. He sat down. I apologize for my behavior earlier.

That’s all right, said Daisy, though she was thinking mostly about Melissa, the drugs, the rudeness, how symbolic it was that she was sitting outside in a cold dark place. If only she were able to look up to the light then Daisy could reach down and take her hand.

It was very bad manners. I’m sorry.

The front door clicked and thumped again. Melissa passed across the yellow rectangle of the lit hallway waving at them. Nighty-night, campers.

Louisa got to her feet. I’m going to have words with that girl. And she was gone.

Dominic patted Richard on the shoulder. She’s a teenager. Your job is to be completely and utterly in the wrong.

The Smoke Man ran toward him, roaring and swinging the spiked mace around his head. Benjamin pulled the flintlock out of his pocket and fired. The Smoke Man’s mask cracked and the brown gas hissed into the cold air. He screamed and fell to his knees. Nizh … Nizh … He grabbed the pipe from the breathing tank and shoved it directly into his mouth, sucking furiously.

No, Melissa, you listen to me. I know I can’t tell you what to do. You have made that abundantly clear. But if you try to drive Richard away … I was treated like a doormat by my parents. I was treated like a doormat by my brothers. I was treated like a doormat by your father. I am happy for the first time in my life. Richard loves me. Richard respects me. Richard is kind to me. If you destroy this, I swear to God …

My fairy lord, this must be done with haste,

For night’s swift dragons cut the clouds full fast;

And yonder shines Aurora’s harbinger,

At whose approach ghosts, wand’ring here and there,

Troop home to churchyards. Damned spirits all

That in cross-ways and floods have burial,

Already to their wormy beds are gone,

For fear lest day should look their shames upon;

They wilfully themselves exil’d from light,

And must for aye consort with black-brow’d night.

He rolled over and lay there, watching her sleeping. The butter-colored hair, the pink of her ear. He touched her shoulder gently so that she didn’t wake. There are so many things you do not know about my mother.

Lord, said Daisy, make me an instrument of Your peace; where there is hatred, let me sow love; where there is injury, pardon; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light; where there is sadness, joy …

The witching hour. Deep in the watches of the night, when the old and the weak and the sick let go and the membrane between this world and the other stretches almost to nothing. The moon white, the valley blue. She stands on the hill. The animals sense something out of kilter and move away. Rabbits, mice, nightjars. She gazes down toward the house. The porch light comes on and goes off again. A lamp burns in a bedroom window. Stone walls still holding the heat of the sun. She begins to walk, the grass wet under her bare feet. She climbs a stile over a drystone wall and cuts diagonally across the field below. The lamp in the bedroom window goes out.

She pushes through a low stand of gorse to reach the track which curls around the house. Thorns rip her dress and when she steps onto the broken limestone there are gashes on her thighs and calves that drip and glitter. Someone turns and settles in their shallow sleep.

The lure of human things. She circles the house counterclockwise then steps under the porch. The door means nothing to her. She stands on the cold flags of the hallway, coats like bats on their brass hooks, the mess of shoes. She can feel it all, centuries of habitation, paint over paint over plaster over stone.

Her mother and father are sleeping in the room to her left. She moves down the corridor, puts her hand on the little metal dog’s head of the newel post and makes her way upstairs. The old planks are silent under her feet. Beeswax and camphor, little bouquets of lavender hung in wardrobes. At the top of the stairs there is a print of a bear and a dog fighting. That human smell. Musk, sweetness, rot. She walks along the landing and into the bedroom.

The Art of Daily Prayer. Neutrogena hand cream. Jeans, knickers and navy smock folded on the seat of the chair. The girl turns on her pillow, hands fighting their way through imaginary cobwebs. She knows someone is in the room. She moans something that is not a word.

Does she hate this girl or love her? Perhaps everyone thinks that about their sister. Is this the girl who stole her life? Or is this the girl she would have been? She reaches down and lays her hand against the side of Daisy’s head. She struggles but Karen doesn’t take her hand away.