Introduction

DREAMS DEFERRED AND DERAILED

PATRICIA ARRORA’S STORY COULD HAVE TAKEN MANY TURNS.

The daughter of a single mom who worked as a maid until she became disabled, Patricia grew up in the crime- and drug-plagued neighborhood of Watts, in South Central Los Angeles. At an early age, she became a single mother herself and began collecting welfare benefits. But although Watts’s troubles defined Patricia’s early years, a desire to move up and away from her hometown’s ills—its bad reputation, its gangs, and its drugs—motivated her subsequent life’s journey. Despite challenges and detours along the way, she has secured many of her dreams. But her path was harder than it had to be. For African American single moms like her, and for many other Americans, barriers to prosperity are too high to overcome through individual achievement, and success is rarer than it should be.

My colleagues and I first met Patricia in 1998, when she was forty-six years old. Hers was one of 187 families across the United States that we interviewed in hopes of learning how differing wealth resources shape the plans, opportunities, and futures of individuals from different walks of life. We wanted to understand how people chose schools for their children, decided where to live to best accommodate their family’s needs, and planned to achieve economic mobility. We were also eager to learn about the different pathways that lower-income families and families of color must take as they strive for better lives.

We recruited families from child-care centers and through word of mouth in Boston, Los Angeles, and St. Louis. By design, about half of the families we interviewed were white, and half were African American; half were middle-class or better-off, and half were working-class or poor; half resided in the three cities themselves, and half lived in suburbs of those same metropolitan areas. From the interviews we conducted in the late 1990s, we gleaned invaluable insights into the hopes, dreams, and difficulties of a wide swath of American families.1 But we learned far more when we checked back with these families over a decade later.*

Between 1998 and 2010, when we conducted our first follow-up interviews, the Great Recession and implosion of the US housing market hit hard. Beginning in late 2007 and officially ending in mid-2009, this crisis profoundly impacted families nationwide. In the wake of the recession, between 2010 and 2012, the team contacted and interviewed 137 of the 187 families interviewed twelve years before. Technically speaking, the recession was over, but our conversations revealed that the crisis was clearly still unfolding. Most of the families we talked with were reeling from job losses, adjusting to reduced incomes, or having trouble making mortgage payments. One adult in fifty-three of the families had lost his or her job during the recession; fifty families experienced lower incomes at some point during the recession; and at least a dozen had fallen behind on their mortgages. Seven families lost their homes due to foreclosure.

By 2012, those who had been children when we conducted our first set of interviews were now young adults finishing high school, planning for college, entering the workforce, or starting families of their own. The parents we spoke to in 1998 were now in a position to tell us how their plans had worked out and how their resources had affected their own mobility and that of their children. With these two sets of interviews in hand, we traced the divergent advantages and challenges associated with race and economic status that confront families striving to move ahead in the United States. The interviews underlined how we must understand economic and racial inequality in tandem, how vast wealth disparities and racial injustice do real harm to individual families, and how powerful institutional forces, rather than individual choices, distinguish those families who get ahead from those stuck in place or falling behind. The story of Patricia and her family illustrates many of these themes and exemplifies the political and economic structures that at times helped launch her economic mobility and at others destroyed her wealth.

When we first talked to Patricia Arrora at her apartment in 1998, she had just moved herself off of social assistance. She and 13 million other people had been receiving cash assistance when the program known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) ended in 1996. Subsequent economic growth pulled her and others from welfare into paying jobs and by 2000 had, along with new rules restricting eligibility for social assistance, halved the rolls in the program that replaced AFDC, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. When we spoke Patricia had taken a job processing applications for a local utility company in Los Angeles County, and the probationary salary put her family’s income just below the federal government’s official poverty threshold. This threshold is the minimum level of income deemed adequate to feed, clothe, and house a family; it is calibrated by family size. The calculation is based on this standard, as is eligibility for some government programs. For Patricia’s family of three in 1998 the poverty line was $13,650. Patricia wistfully told us that she was looking to meet a millionaire to rescue her. Still, if she succeeded past the probationary period and secured a permanent position, the annual pay of $19,800 (in 1998 dollars) would nudge Patricia and her four- and five-year-old daughters just above the poverty line. A job paying less than $20,000 a year may not sound like much, and Patricia had no financial wealth: no savings, stocks, bonds, property, or car, and certainly no pension or other retirement plan. But for Patricia, the job represented a huge and proud step up.

Sitting in her apartment in 1998, Patricia told us how she had taken classes to learn computer skills, gaining experience that paved the road away from AFDC and helped her secure employment. Having a job and knowing that tomorrow would bring a stable, earned paycheck was crucial to Patricia’s identity and dignity. Although eager to bring home more than the $700 monthly welfare payments she had been receiving, she also longed for the sense of self-esteem that came with work. Some critics view poor people as suffering from character defects, such as a lack of ambition or work ethic, welfare dependence, or an inability to defer gratification. Patricia didn’t actually have these traits.

In addition to work and money, housing and community were constant concerns in Patricia’s life. In 1998, she was living in subsidized rental housing in West Los Angeles, fourteen miles west of Watts, a neighborhood that offered too many traumatic reminders of where she had grown up. Patricia feared the menacing guys who hung out on the nearby street corner. She hoped to buy a home in a safe, welcoming community where her daughters could thrive—a winning, and very American, plan.

Our interview with Patricia in 2010 revealed that she had made good on that plan, but not without great struggle. In 2003, she purchased a home in a different neighborhood in West LA with the assistance of the Family Self-Sufficiency program of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Residents living in public housing or receiving rent subsidies pay 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities. Increases in work income get siphoned off by higher rent, which potentially creates a work disincentive. The program permits families receiving rental subsidies to place in escrow the rent increases that usually accompany increased earnings, enabling families to simultaneously increase their earned income and to save money to improve their lives. Patricia used the escrowed monies as a down payment on a home. The new neighborhood featured open spaces, greater safety, and comparatively high-quality schools. But the community still reminded her of Watts. Even though her family was moving up, Patricia was not happy with what she described as a “drug-infested, gang area.” She recalled a couple of incidents in which gangs had approached relatives, making the family reluctant to venture out to neighborhood stores. Despite precautions, their house was robbed. She “felt violated,” and the “kids didn’t want to sleep in their bedrooms.… They were afraid.” It was time to move again.

In 2006, Patricia leveraged first-time home ownership with equity built up in Los Angeles’s hot housing market to buy a larger, brand-new home sixty miles away in Los Angeles’s Inland Empire exurbs (Riverside and San Bernardino counties). Shortly thereafter, however, the housing crisis and the Great Recession wreaked havoc on the family’s hard-earned success and imperiled Patricia’s plans for her children’s future. In 2010, some two years after the crisis, we sat down with Patricia in the kitchen of her Riverside-area home. She now earned a middle-class income of $50,000 annually and had financial assets amounting to $7,000, putting her family above the asset poverty line—the minimum amount of wealth needed to keep a family out of poverty for three months. Her family had expanded as well. Patricia had married Frank in 2003. After working for years at a good union job, Frank had been unemployed since 2008, and he was still collecting unemployment. His inability to contribute financially to the household was a source of family tension.

Patricia was happy with her home. She described how she took equity built up in her first home in West LA, gave a large sum to her mother and other kin to help them out, and used the rest to put a $112,000 down payment on the new home. Yet, the housing crisis hit hard and not all was right financially. The balance Patricia owed on her mortgage exceeded the home’s plummeting value. The loan terms prohibited her from refinancing. With her husband out of work, she was struggling to make mortgage payments on one income, and she had entered a government-sponsored loan modification program. Patricia was stuck paying other bills on credit cards.

And although pleased with her home, Patricia was unhappy with the neighborhood high school, which she described as “run down… dirt.” The school’s test scores, well below California’s average, corroborate Patricia’s observation. Reflecting area demographics, 96 percent of the high school’s students are youths of color, and nearly three-quarters qualify for subsidized lunches because they come from families with incomes 185 percent below the poverty line.2 So Patricia enrolled her girls, Brittany and Brianna, in a different high school fifteen miles from their new home. Both girls ran track and hoped to go to college. One had a 3.5 GPA and expected to go to a state college on a scholarship. The other struggled with juvenile diabetes, which had compromised her energy and ability to concentrate, and her GPA hovered around 2.0. Patricia had told the girls that because she couldn’t afford to take on any additional debt, they would have to get scholarships and financial aid to continue their education.

Patricia liked the quiet and safety of her subdivision, but she worried she had made a mistake moving somewhere so isolated from public transportation. Patricia drove the girls twenty minutes to their high school, which was out of her way; because she would also have to drive them to any part-time job they might find, they were effectively unable to work. The girls wanted a car to get around, but Patricia was unable to afford one or the added insurance, so she insisted they ride the bus. For the girls’ benefit, she attempted to use the situation to teach some difficult lessons, telling them that she had come up hard and that they must pay for their own transportation, “because it won’t be coming out of my pocket.”

Overrun by foreclosures during and after the crisis, Patricia’s subdivision was changing rapidly around her. During our interview she estimated that at least ten houses were on the market in the neighborhood at that moment, and I noticed “for sale” signs on about every third house, with dried-up and unkempt lawns throughout the neighborhood. People were just “walking away from their houses,” Patricia reported. She had been especially fond of one neighboring family, but when they couldn’t afford to make their payments, they left. Within one mile of Patricia’s home, sixty-eight families lost homes due to foreclosure between 2008 and early 2013. Indeed, Patricia’s subdivision illustrates the broad destruction of family wealth in the Inland Empire, where 54.9 percent of home owners owed more on their mortgages than the homes’ value in late 2009; by early 2013, 35.7 percent were still “underwater.” In recent years, Wall Street investment firms have issued securities and amassed billions in funding to buy foreclosed homes. In March 2013, for instance, investors bought up 57.8 percent of the Inland Empire homes made available through the foreclosure process before they ever reached the open market.3

The high number of foreclosures in the neighborhood was not a matter of chance. KB Home, purveyors of the American dream, had developed Patricia’s subdivision. KB’s gated master-planned communities, located throughout the Inland Empire, feature swimming pools, walking trails, tot lots, and parks.4 KB also connects potential buyers to financial services, which is how so many buyers in Patricia’s neighborhood came to get mortgages from Countrywide Financial Corporation. One of the biggest mortgage lenders in the Inland Empire, Countrywide also became the poster child for predatory lending. In 2015, in a $335 million settlement with the US Department of Justice, Countrywide stipulated that it had discriminated against more than 200,000 African American and Hispanic borrowers between 2004 and 2008, steering them toward subprime loans and charging higher fees and interest rates, even though those borrowers had credit profiles similar to white borrowers who received prime loans.5 Patricia was one of those borrowers. She felt cheated by the terms of her mortgage; by the close relationships between KB Home, the mortgage appraisers, and Countrywide; and by a large “hidden” fee that unexpectedly appeared at the closing. Such fees were a part of Countrywide’s business model because it was a mortgage machine with subsidiaries providing services and extracting fees throughout loan applications, lending, and servicing. In a separate settlement, the Federal Trade Commission determined that Countrywide had bilked 450,000 customers by overcharging on services, even charging some borrowers whose homes were in foreclosure $300 to mow their lawns. Countrywide paid the Federal Trade Commission a settlement fine of over $1 million. Like Countrywide, KB Home settled several class-action lawsuits related to its practices, stipulating that it had approved loans to borrowers who were not eligible, approved loans based on overstated or incorrect income, failed to include all of borrowers’ debts, and failed to properly verify sources of funds.6

Toxic mortgages were not the only thing poisoning Patricia’s neighborhood. Several miles away are the Stringfellow Acid Pits, a site so contaminated by hazardous waste that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) declared that it poses a risk to human health and the environment. Beginning in 1956, major corporations dumped 34 million gallons of industrial waste into an unlined evaporation pond at the site. The contaminants, which came from producing metal finishing, electroplating, and DDT, migrated into the underlying, highly permeable soils and then into the groundwater table, resulting in a contaminated plume extending two miles downstream. The EPA has cited seven additional polluters in the neighborhood. Stringfellow has affected the local drinking water supply and negatively impacted home values.7

Much as she preferred her new home to living in Watts or West LA, Patricia had bought into a new development at the worst possible time. The house for which she paid $386,000 in 2006, with a huge down payment, was valued at a little over $300,000 by late 2014. Due to a combination of bad timing and fraudulent mortgage products, many on her block and in her neighborhood had lost their homes and, with them, all of their wealth. Patricia still had her home, but when we talked in 2010, she had lost the $112,000 down payment and all her equity. She lamented, “Now, there’s nothing there. All the equity is gone, and I still owe more than the house is worth.” When Patricia applied to modify her loan, she told the loan modification program officer that she “was burned… bit by a shark.” Angry at being a casualty of the real estate market, she declared that she wished she had kept her money under a cushion. Home ownership was meant to provide for her retirement and to help her two daughters pay for college. In 2010, her retirement plan was in jeopardy, and her daughters needed scholarships and loans to continue their educations.

When I returned to Patricia’s neighborhood in early 2015, things were looking better. There were no “for sale” signs, the houses looked to be in good repair, and all of the lawns were spruced up. One might never guess that the subdivision had been ravaged by the foreclosure crisis and witnessed a tremendous stripping of housing wealth. The market had culled those who could not keep up with their mortgages, who lost jobs, or who were working at lower salaries. The fortunes of families and communities can change quickly, and seeing clearly the challenges people face and how they adapt to them requires following their trajectories over a period. Today, Patricia is meeting the challenges thrown her way. Without marrying a millionaire, she has recovered from credit card debt and aims to be debt-free. Her house’s value is stabilizing, even rising, while her modified mortgage is affordable, reducing her monthly payments by $500. She has a savings goal of “at least $10,000 a year,” she tells me. “Put it like that.” Accompanying her new economic stability is a perceptible sense of optimism in her attitude. Today, she feels secure, “really fortunate and blessed.” To Patricia, the future looks bright.

Patricia Arrora’s story is indicative of the crucial factors shaping the ups and downs of American family life and economic mobility today. With hard work and home ownership she gained dignity, respect, and upward mobility. She overcame recession and foreclosure challenges that often result in downward mobility. Most importantly, she faced and triumphed over challenges that made her path harder than it ought to have been: race and lack of wealth.

IN RECENT YEARS, AS LIVING STANDARDS FOR MANY FAMILIES have declined and productivity, income, and wealth gains have flowed to the very top, a new conversation about inequality has emerged in the United States. The Occupy Wall Street movement, which began in the fall of 2011, splashed inequality across the front pages and provided space for discussions about historically high income and wealth disparities and their causes. The movement pitted the wealthiest and most powerful 1 percent against 99 percent of Americans. Thomas Piketty’s best-selling 2014 book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, brought attention to a different kind of inequality with a focus on capital. Yet many popular and academic accounts of inequality, spurred by media coverage and the emerging national discourse, continued to focus on income disparities, economic class, and the mega-rich. A preoccupation with income led to an insufficient understanding of the new inequality that left wealth out of the picture. President Barack Obama provided perhaps the crowning moment in this new public attention to economic inequality when he proclaimed in a December 2014 speech that inequality “is the defining challenge of our time.”8 But the president’s speech referenced income inequality eleven times and wealth inequality once. Leaving wealth out of the conversation is a crucial mistake, giving fodder to those who would make personal poverty the result of personal failings.

Wealth inequality in the United States is uncommonly high. The wealthiest 1 percent owned 42 percent of all wealth in 2012 and took in 18 percent of all income. Each year the Allianz Group, the world’s largest financial service company, calculates each country’s Gini coefficient—a measure of inequality in which zero indicates perfect equality and one hundred perfect inequality, or one person owning all the wealth. In 2015, the United States had the highest wealth inequality among industrialized nations, with a score of 80.56.9 Allianz dubbed the USA the “Unequal States of America.”

Wealth concentration has followed a U-shaped pattern over the last hundred years. It was high in the beginning of the twentieth century, with wealth inequality reaching its previous peak during the Depression, in 1929. It fell from 1929 to 1978 and has continuously increased since then. By 2012, the share of wealth owned by the top 0.1 percent was three times higher than in the late 1970s, growing from 7 percent in 1979 to 22 percent in 2012. The bottom 90 percent’s wealth share has steadily declined since the mid-1980s.10

The rise of wealth inequality is almost entirely due to the increase in the top 0.1 percent’s wealth share. The steady decline in the bottom 90 percent’s wealth share has struck middle-class families in particular. Half the population has less than $500 in savings. In our interviews we heard the concerns of those who had more month than paycheck.11

Wealth is not just a matter of money. As our interviews revealed, wealth is also about power, status, opportunity, identity, and self-image. Wealth confers transformative advantages, while lack of it brings tremendous disadvantages. A family’s income reflects educational and occupational achievements, but wealth is needed to solidify these achievements to build a solid foundation of economic security. Wealth is a fundamental pillar of economic security, and without it, as many of the families we interviewed experienced firsthand, hard-won gains are easily lost.

The explanations for economic inequality are many. One prominent line holds that individual values and characteristics either promote or hinder achievement and prosperity. Inequality, in this view, results from poor people’s laziness and lack of work ethic, the decline of traditional marriage, an influx of unskilled, uneducated immigrants, and dependence on welfare. Our interviews contradict such arguments—the people we spoke with, rich and poor, had broadly similar values and aspirations—and reveal instead the importance of policy and institutional factors. Other theories focus on such factors as market forces in a globalizing economy, technological change, policies, and politics.12

This book takes a different tack, arguing that we must understand wealth and income inequality together with racial inequality. Despite recent attention to racial disparities in policing, mass deportation, persistent residential segregation, attacks on voting rights, and other manifestations of racial injustice, the conversation about widening economic inequality largely leaves out race, as if that gap’s causes, its harshest consequences, and its potential solutions are race neutral. Whether they focus on the widening gulf between the very top and various segments further down the distribution ladder, on the fortunes of the bottom 40 percent, on the dwindling of the middle class, or simply on the growing share garnered by the best-off, traditional accounts emphasize class and economics as the central (and sometimes only) explanation. As a result, much of our national discourse about inequality sees disparities as universals that impact all groups in the same ways, and many of the policy ideas proposed to address it fail to recognize the racially disparate distributional impact of universal-sounding solutions.13 Recent movements such as the Color of Change, the Dreamers, and Black Lives Matter are vigorously trying to recenter the inequality conversation to include race, ethnicity, and immigration. I have been inspired and heartened by the new public conversation about inequality. At the same time, I am frustrated that once again it looks like attention to class is trumping a reckoning with race.

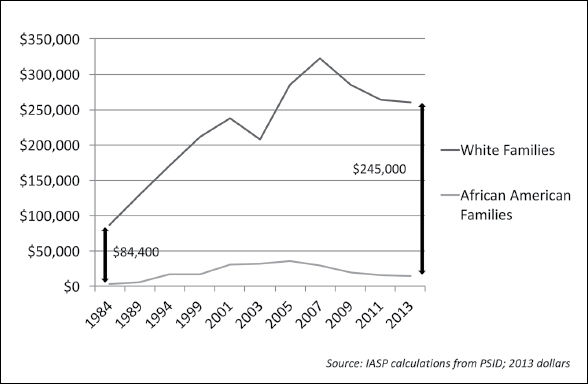

For it is crucial to understand that the trends toward greater income and wealth inequality are converging with a widening racial wealth gap. The typical African American family today has less than a dime of wealth for every dollar of wealth owned by a typical white family. The civil rights movement and the landmark legislation of the 1960s helped to open educational and professional opportunities and to produce an African American middle class. But despite these hard-won advances, as a study following the same set of families for twenty-nine years shows, the gap between white and black family wealth has widened at an alarming pace, increasing nearly threefold over the past generation (see Figure 1.1). Looking at a representative sample of Americans in 2013, the median net wealth of white families was $142,000, compared to $11,000 for African American families and $13,700 for Hispanic families. This racial wealth gap means that even black families with incomes comparable to those of white families have much less wealth to use to cushion unemployment or a personal crisis, to apply as a down payment on a home, to secure a place for their families in a strong, resource-rich neighborhood, to send their children to private schools, to start a business, or to plan for retirement.

In short, the basic pillars of economic security—wealth and income—are today distributed vastly inequitably along racial and ethnic lines. African Americans’ historical disadvantage has become baked into the American economy. African Americans are effectively stymied from generating and retaining wealth of their own not simply by continuing racial discrimination but also by senseless policies that protect existing wealth—wealth that often originated at times of even more intense racial discrimination, if not specifically from racial plunder. Race and wealth have intertwined throughout our nation’s history. Too often missing in today’s dialogue about inequality is this binding race and wealth linkage. Failure to tackle the nexus of race and wealth will lead, at best, to only small ameliorations at the worst edges of inequality.

Figure 1.1 Median Net Wealth by Race, 1984–2013

Major demographic shifts that are increasingly diversifying America and threatening to sharpen racial and ethnic fault lines further exacerbate the dangers of historically high wealth and income inequality and a widening racial wealth gap. America is becoming a majority-minority nation. Newborns of color outnumbered white newborns for the first time in 2013. America’s population growth stems from higher birth rates among families of color and from immigration, especially among Asians and Latinos, while its white population is aging. In 2014, only 21 percent of seniors, but 47 percent of youth, were nonwhite. Demographics are not destiny; yet our institutions, from schools to the workforce to communities to government, are just beginning to confront challenges of racial diversity they were not designed to face, are ill prepared to meet, and often resist. Our institutions grew out of an assumed everlasting, politically dominant white majority. The nation has not yet imagined who we are together.

The phrase “toxic inequality” describes a powerful and unprecedented convergence: historic and rising levels of wealth and income inequality in an era of stalled mobility, intersecting with a widening racial wealth gap, all against the backdrop of changing racial and ethnic demographics.

I call this kind of inequality toxic because, over time and generations, it builds upon itself. Wealth and race map together to consolidate historic injustices, which now weave through neighborhoods and housing markets, educational institutions, and labor markets, creating an increasingly divided opportunity structure. So long as we have entrenched wealth inequality intertwined with racial inequality, we cannot even begin to bend the arc toward equity.

Toxic inequality is also noxious in that it makes these challenges harder to tackle. High levels of material inequality are inherently destabilizing, heightening social tensions. Janet Yellen, chair of the board of governors of the Federal Reserve System, has warned that economic inequality “can shape [and] determine the ability of different groups to participate equally in a democracy and have grave effects on social stability over time.”14 Thomas Piketty argues that extremely high levels of wealth inequality are “incompatible with the meritocratic values and principles of social justice fundamental to modern democratic societies” and warns that a drift toward oligarchy is a real danger.15 The new inequality is especially politically poisonous because most people of all races feel stuck in place, finding it harder to believe that hard work, sacrifice, and innovation are going to pay off and lead to a better life. People are apt to look for someone to blame, and America’s changing demographics encourage racial division, resentment of other groups, and prejudice. These forces have complicated economic policymaking throughout our history, but they are especially dangerous today, given the urgent need to address the particular economic disadvantages facing people of color.

We are just beginning to understand one further dimension of toxic inequality: a phenomenon we might call “toxic inequality syndrome.” Are there emotional and even physiological consequences for families and individuals exposed to repeated, persistent economic trauma, frustrated ambitions, and cumulative downward spirals? We know that there is a strong relationship between adversity and social outcomes throughout the life course, with greater frequency of adverse events leading to worse outcomes.16 One adverse event increases the likelihood of a cascade of other stressful and traumatic events. Research has documented the negative impact of a wide variety of stress-inducing events, including community violence, accidents, life-threatening illnesses, loss of economic status, and incidences of racism. We also know that financial resources shield families from economic and social trauma, lessen the impact of some trauma, enable more rapid recovery, and reduce the risk of subsequent adverse events.17 Yet many of the families we spoke to experienced multiple forms of adversity—foreclosure, violence, unsafe neighborhoods, incarceration, disability, sudden or chronic family illness, family breakup, unemployment or loss of wages, declining living standards—without adequate wealth resources and without the sorts of family, institutional, community, or policy support that can also foster family resiliency. In the stories in subsequent chapters, we will encounter amazing resiliency, and we also will meet families who became overwhelmed by the stress and trauma associated with toxic inequality.

America’s response to toxic inequality will set our future course for generations. The current magnitude of inequality robs the nation of human potential and promise, sapping aspirations and distorting futures. Earned achievements have become uncoupled from financial rewards and personal well-being. Frustrated ambitions and stalled social mobility foment racial anxieties. Without bold changes, we will keep heading toward greater inequality and become even more polarized along class and racial lines. The tiny segments of the population that are doing well will continue to do so, and the vast majority will try even harder just to stay in place. The rich and powerful will continue to write rules that protect and expand their vast advantages at the expense of those struggling to keep pace, especially younger adults and families and communities of color. As differences magnify, those groups facing the brunt of inequality, stalled mobility, and lost status will more critically interrogate the legitimacy of governmental and economic systems. Such an interrogation of deep structures is necessary and productive as long as it uncovers drivers of inequality. However, an explanation that does nothing more than pander to racial, ethnic, and class fears will short-circuit solutions. To avoid this bleak future and bend current trends in the direction of shared prosperity, we must transform the deep structures that foster inequality. Policy solutions must be bold, transformative, and at a scale sufficient to reach the families and communities most affected by toxic inequality.

THIS BOOK PLACES OUR FAMILY INTERVIEWS FRONT AND center in building a comprehensive understanding of what toxic inequality is and why it matters so much, and it proposes proven, evidence-informed policy solutions that can equitably increase prosperity for American families. Patricia Arrora’s story captures the major themes of well-being, opportunity, and inequality in the United States. Wealth, or its absence, begins where we begin: in the neighborhood where we are born. Work helps us improve our earning power and shapes our adult lives. In time, if we’re born to the right family in the right neighborhood, if we secure the right job, and if the policy landscape favors it, we might amass a certain amount of wealth. At the end of the day, we might pass that wealth to the next generation in the form of inheritance. And through it all, government policies can either help multiply our opportunities and our wealth or obliterate them. Patricia’s story turns on these key factors: wealth and financial resources; community, home, and family; work; inheritance and kin networks; and the opportunities and challenges posed by government policy. This book’s organization reflects those themes, drawing throughout on our team’s interviews with families in 1998 and 1999 and from 2010 to 2012, supplemented by nationally representative data, in the hopes of illuminating how these factors work together to shape a family’s well-being.

The first chapter looks squarely at how families accumulate wealth, not primarily as an end in itself but as a tool to stave off crises and create advantages and opportunities for mobility. It also examines how the absence of wealth turns small crises into major disasters, severely narrows opportunities, and inhibits mobility. The stories of the Breslin and Johnson families make these dynamics clear. They also reveal the importance of kin and family networks. Successful families of color are more likely than middle-class white families to need to help out relatives or friends in times of need, and when they do so, they have fewer resources left over to move ahead themselves.

Our examination then moves in Chapter 2 to homes and communities, the largest reservoirs of wealth and opportunity for the vast majority of families. Chapter 2 explores the story of the Andrews family, whose challenges and decisions highlight the enduring significance of race and economics in home values and the advantages and disadvantages of neighborhoods and location. The stories of three other families in this chapter further illustrate how neighborhood inequality powerfully shapes the overall contours of toxic inequality.

The book then turns from home to work. Chapter 3 introduces the Ackermans, whose story affords us a broader understanding of how jobs, income, and benefits drive opportunity and inequality. Earnings convert to wealth differently according to a job’s benefit structure. Access to the kinds of workplace benefits that result in wealth accumulation and greater mobility varies according to work sector and is thus shaped by occupational segregation. Other family interviews illustrate how minority workers’ income is comparatively isolated from wealth-growing mechanisms. Pay stubs approaching parity hide systematic discrimination that drives both the wealth gap and the widening racial wealth gap.

Some fortunate families have wonderful head starts in life, with wealth facilitating multiple chances to succeed even in the face of challenges. Chapter 4 examines the important matter of inheritance. We meet the Clarks, whose inherited wealth permits a kind of life well beyond the means of their earned income. Their children attend strong, resource-rich private schools and grow up in an upscale neighborhood. A look at other families illustrates the kinds of benefits that smaller inheritance and transfers transmit. Those without such transfers suffer as a result.

In all of these realms, government policy functions to increase inequality. In theory, the goal of social policy is to widen opportunities, minimize barriers to success, promote well-being, and help build equity into prosperity. But Chapter 5 demonstrates that the distributional effect of core government policies is actually to create, maintain, and widen inequality.

Our exploration of toxic inequality concludes with a look back at the families we have met throughout the book, interrogating how it might be in our power, as a country, to change their lives for the better. A mobility policy agenda would include family wealth-building policies such as children’s savings accounts, an expanded Family Self-Sufficiency program, housing mobility and stability measures, and policies concerning better wages and benefits and family supports. An equity agenda would reform existing policies that deepen inequality, such as the tax code’s treatment of mortgage interest, retirement contributions, and inheritance. The book’s policy recommendations offer a path toward changing the lives of the families our team met and stemming the tide of toxic inequality for all.

Patricia Arrora is one of the nearly two hundred individuals or couples who shared their dreams and disappointments, joys and sorrows. One life story cannot capture the complexity and individuality of American families and their struggle for a better life, but Patricia’s story and others collectively help to reveal how toxic inequality stymies family, community, and economic well-being. This is why real people’s lives are at the core of this book. Far too often, toxic inequality has kept them from achieving the full scope of their dreams for themselves and their children. The first step toward making change is to tell their stories and understand how their individual challenges connect to the powerful forces that have brought us all to this moment of crisis.