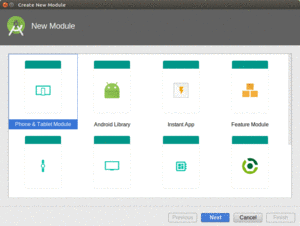

Figure 312: Android Studio New-Module Wizard, First Page

Android library modules are the primary unit of Android source reuse, particularly where that source involves more than just Java source code, such as Android resources.

In this chapter, we will explore the basics of setting up and using an Android library module.

Understanding this chapter requires that you have read the core chapters of this book.

An Android library module, in many respects, looks like a regular Android project. It has source code and resources. It has a manifest.

What it does not do, though, is build an APK file. Instead, it represents a basket of programming assets that the Android build tools know how to blend in with regular Android projects.

Making a project be an Android library module is simply a matter of choosing the right Android Gradle Plugin.

Rather than have:

apply plugin: 'com.android.application'

use:

apply plugin: 'com.android.library'

That’s it — the com.android.library plugin now knows that it is creating

a library, not an app.

The real question is, where are you making this library? In many cases, you will do so as a module in a project, where there is another module that is an app. This covers both:

Adding new modules to an Android Studio project is handled most simply via the new-module wizard, which you can bring up via File > New > New Module… from the main menu. This brings up the first page of the new-module wizard:

Figure 312: Android Studio New-Module Wizard, First Page

To add a library module as a module to an existing project, choose “Android Library” in the list of module types, then click Next to proceed to the second page of the wizard:

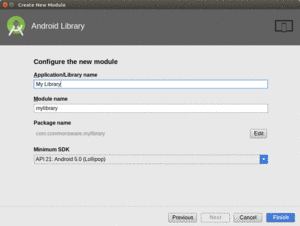

Figure 313: Android Studio New-Module Wizard, Second Page

This collects some bits of information, including:

minSdkVersion

At this point, clicking Next will take you to the same new-activity flow that you saw when creating a new project. If you want an activity to be generated for you in this library, proceed by selecting the activity template and providing the activity template configuration data. If you do not want an activity, choose “Add No Activity” in the grid of templates, then click “Finish” to create the module.

In the end, the new-module wizard will set up the new module for you, in

your designated subdirectory of the project, including modifying settings.gradle

to list this subdirectory as being a module within the project. At this

point, you will be able to start using the library within the project itself.

Once you have a library module, you can attach it to another Android

module, so the other Android module has access to everything in the

library. This works similarly to adding other sorts of dependencies,

with a slight syntax change. Rather than use an artifact identifier

or fileTree(), we use project():

implementation project(':libname')

where libname is the name of the module. This will be the directory

name, and it will also show up as the module’s name in settings.gradle

in the project root directory:

include ':app', ':libname'

The leading colon means that this module is directly off of the project root directory.

If you wish to use this library module in separate projects, other than the one that hosts the module, you will need to distribute it to those other projects. A typical way to do that is to compile the library module into an AAR file and have that be hosted in an artifact repository.

Library projects can publish their own AndroidManifest.xml file, which

contributes to the overall manifest used by apps that incorporate the library.

Hence, a library can:

However, merging these manifests is a rather complex topic, and as such will be covered much later in the book.

Just as an application module can have dependencies, so can a library module. For other modules that depend upon the library module, the library module’s dependencies become transitive dependencies. In other words, if App A depends upon Library B, and Library B depends upon Library C and Library D, App A has transitive dependencies on Library C and Library D.

When a module depends directly upon a library module (e.g., implementation project(':libname')),

all of that library module’s dependencies get added to the requesting module’s

dependencies list. The same holds true when a module depends upon a library

from an artifact repository. It does not hold true for bare libraries,

such as adding plain JARs to a project via implementation fileTree(...).

There are three key ways that a library module can declare a dependency:

implementation, api, and compileOnly. While an app module typically would

only use implementation, all three of these options are possible for a library

module, with subtly different behavior:

| Configuration Name | Is Dependency’s API Available to Hosts? | Is Dependency’s Code Added to Hosts? |

|---|---|---|

implementation |

no | yes |

api |

yes | yes |

compileOnly |

no | no |

Let’s examine a concrete example: CWAC-NetSecurity. This library — which will be profiled later in the book — has its own code, plus it has helper code for integrating the library’s code with OkHttp. There are three ways that CWAC-NetSecurity could declare its dependency upon OkHttp, and those choices change what happens in an app that itself depends upon CWAC-NetSecurity:

implementation to depend upon OkHttp, then

an app that depends upon CWAC-NetSecurity gets both CWAC-NetSecurity and

OkHttp code added to the app (“Is Dependency’s Code Added to Hosts?”). However,

the OkHttp code itself is not deemed to be part of the API of CWAC-NetSecurity,

and so the app that depends upon CWAC-NetSecurity cannot use the OkHttp classes,

unless it has its own separate implementation dependency upon OkHttp.api to depend upon OkHttp, then as with implementation,

both the code from OkHttp and the code from CWAC-NetSecurity get added to apps

that depend upon CWAC-NetSecurity. However, in this case, the app can directly

refer to classes from either CWAC-NetSecurity or OkHttp, without an additional

dependency declaration. In effect, CWAC-NetSecurity is stating that OkHttp

is part of CWAC-NetSecurity’s public API.compileOnly. This says

that OkHttp is used only to be able to compile CWAC-NetSecurity’s own code.

The OkHttp code is not added to apps that depend upon CWAC-NetSecurity, unless

those apps have their own implementation dependency upon OkHttp.implementation and api are the two most common. compileOnly is mostly

for cases where the library module would like to offer integration for some

third-party library, but where that library is not essential. For apps that

want to use the integration, they simply need to have an additional dependency.

For apps that do not want the integration, though, they avoid having all the

extra code added from the third-party library.

While library modules are useful for code organization and reuse, they do have their limits.

As noted above, if more than one project (main plus libraries) defines the same resource, the higher-priority project’s copy gets used. Generally, that is a good thing, as it means that the main project can replace resources defined by a library (e.g., change icons). However, it does mean that two libraries might collide. It is important to keep your resource names distinct to minimize the odds of this occurrence.