|  |

IT HAD BEEN TWO WEEKS since Mary had arrived back in Duluth, after legal arrangements were made for her departure from Chippewa County. She kept pondering everything that had happened—the good and the bad. There was plenty of both. It was quite incredible, all that she had gone through.

She was sitting in the library of the big house on East Superior Street, late on a warm Thursday afternoon in July, knitting. Emma Beach had placed the basket full of wool yarn and needles in front of her. “Best to occupy yourself with something worthwhile,” she had said. And so Mary began on a pair of mittens that would join others destined for the orphanage this Christmas.

She couldn’t quite say which disaster had made her father angrier. The matter of Agnes Olcott, and Mary’s unintended crime spree at its conclusion? Or his sister Christena’s decision to stay with Paul Forbes for a time, then have him come to Pittsburgh for a visit with her?

Was John MacDougall more aggravated by having his daughter brought before a judge in Sault Ste. Marie? Or by having his beloved little sister take up with a free-spirited photographer? Christena hadn’t even bothered to come back to Duluth, only letting a surprised Mary know of her plan on the platform in Ishpeming. Mary wished she could have stayed there with her aunt, but she had no choice but to return home alone and face the music.

She had never seen her father’s face quite so red or heard his intimidating voice sound quite so fierce. She winced again and again, and very nearly started to cry. But Mary had determined she would sit there and take it. She had earned her dressing-down the hard way, and wasn’t going to sully it—or evade it—by some feminine trick. By sheer force of will, she kept the tears at bay.

“Not only did you go snooping about that asylum quite improperly, and shoot a gun at a man, and damage property, and get arrested, for God’s sake,” John MacDougall had fulminated, standing over her. “You exposed yourself to assault by a dangerous criminal. You put your own dear aunt into a madhouse on the off chance that she would discover a woman thought to be dead. You involved your friend Mr. Roy in the affair and got him arrested. And you got his arm broken, as well!”

“Father,” Mary had replied tremulously, “I am more than willing to repay you for all your costs.” Those, she knew, included the attorneys’ fees, mending the chapel window, and the fines that Judge Tolliver exacted on her, Christena, and Edmond. Not to mention the cost of hiring an engine and carriage to bring Uncle Archie to Sault Ste. Marie. There was also the five thousand dollars that John MacDougall had donated to Westerholm’s trustees by way of apology.

His eyes had widened. “Young lady, that is not the bloody point!” he roared. “You have made a fool of yourself in society. You have my colleagues laughing at me behind my back. You have caused our family name to appear in the newspapers, and not in a flattering way.”

He paused and caught control of his temper. “I would be entirely justified in demanding that you cease this ridiculous detecting obsession of yours. But I have a feeling that, short of locking you up, I wouldn’t be able to stop you. Understand, though, you could have gotten yourself killed.” His voice quieted. “And I would take very cold comfort indeed if, at your funeral, some fellow came up to me and said, ‘Ah, Mr. MacDougall, your daughter, she was a fine detective.’”

Mary had nodded abjectly. However, a little voice in her head riposted that it was a much better epitaph than “She died a boring young woman with piles of money, and not a thought in her head.” Still, she understood her father’s point and genuinely regretted causing him pain.

“I should hope that your recent debacle has convinced you to apply your intelligence and energy to more sensible pursuits.” Her father had finally slumped into the chair opposite her. “Lord knows, I cannot keep an eye on you every moment of every day.”

Thank goodness, thought Mary.

“But you’ll be happy to hear that I’ve arranged for the next best thing.”

Mary steeled herself for an undoubtedly unpleasant surprise.

“You know that your mother’s cousin Jeanette has been through some hard times down in St. Louis.”

Mary did indeed. Emma Beach had already told her that Jeanette had been found and was in straitened circumstances. John MacDougall had only been able to track her down by hiring a detective—a “real detective,” as the housekeeper had said pointedly. The news had come when Mary was off on Mackinac.

“I’ve asked Jeanette to come live with us for a while, and she has agreed. She’s to be your personal secretary and constant companion.”

Mary had been appalled. She liked Jeanette Harrison well enough. But the woman was a little too straight-laced and prudent. A kind of stick in the mud. Not nearly as fun as Christena. And Mary knew perfectly well that Jeanette would serve as a spy for John MacDougall.

“But I don’t need a secretary, Father,” she tried to persuade him. “I’m perfectly capable of taking care of my own affairs.”

He didn’t need to say a word. His expression said it all: Recent events would indicate otherwise.

“As to my sister,” John MacDougall continued, his face darkening again, “the consequences of her little holiday with you are dismaying. And I have no idea how to stop her. You know that Tena hates being told what to do. I’ve never known anyone as stubborn as she is.”

Mary almost said, Well, look in the mirror then, but thought better of it.

After the dust had settled, she had one final thing to be grateful for. Her father—having correctly suspected Detective Sauer’s part in the matter—made no attempt to get him discharged. And when Mary had sought out the policeman at his favored luncheon spot, Salter’s, he expressed his gratitude. But still he had unhappy news for her.

“My boss has told me that he does not want to hear of you visiting police headquarters,” the detective said. “Off limits, I’m afraid. Or next time I really may get the sack. And to be frank, if I’d have known what you planned to get yourself up to out there in Chippewa County, I never would’ve given you the lead. Didn’t I tell you to merely observe and interview and report?”

Mary nodded sheepishly. “That’s what I intended to do. The assault on Westerholm was just sort of improvised.”

He gave her a smile, a rare occurrence. “Yes, well, I have to hand it to you, though. You proved the fraud and unmasked the fraudsters. And at least they didn’t get Mrs. Olcott’s every dime. There’s enough left that she and her company will survive.”

“Have you heard anything more about Olcott and Flugum?”

“Still at large, I’m afraid. Not their real names, of course. They had worked a big flimflam down in Tennessee. Memphis. They used different aliases then. While Olcott cooked the books up in the office, Flugum stole the goods from the warehouse. They managed to disappear back then, too.”

Mary had also sent a letter to Mrs. Tiegland at Westerholm—the poor lady whose husband had abandoned her. Mary told her that the law office of Wilcox and Jameson in Sault Ste. Marie would be in touch with her, regarding representation for her divorce, and possible employment as a cook or housekeeper. This would be at no cost to her good self.

And then there was Edmond Roy.

The parting at the Ishpeming station had been nothing like that in Duluth last December.

They had stood regarding each other nervously, almost as if they had only just met. Mary was already upset because Christena had just walked off with Paul Forbes—having not bothered to tell her niece of her impromptu stay-over until moments before.

“So, I’ll see you in Duluth in a few weeks,” Mary had said.

Like a shy boy, Edmond had kicked at the bricks that paved the platform. “I hope so. I do hope the arm heals up in time.”

“It will,” Mary had said encouragingly, trying to wish that outcome into reality. “Of course it will.”

Edmond’s face showed skepticism.

“We did have some fun, though, on Mackinac, didn’t we?” Mary gave him a bright smile.

“We did,” he nodded with a smile not so enthusiastic. “You are a charming companion.” He averted his eyes. “Most of the time.”

That stung Mary a little. But he was right.

She almost said something about her feelings for him. About how very, very much he meant to her. And about how she couldn’t imagine not having him in her life. But before she could say anything, he quickly leaned over and kissed her.

It was a light brush of lips on her cheek with no hug. Then he offered her a clumsy handshake with his good left hand, said goodbye, and walked away.

Mary couldn’t blame him for having had enough of her.

A few days ago a typed letter from him had arrived that did nothing to cheer her up. In a worryingly formal tone, he explained that Miss Jursik of the Pioneer Bank had graciously agreed to help him with his correspondence while his arm was in the cast. Mary recalled how the young woman’s almond-shaped blue eyes had gazed so admiringly at Edmond, when Mary had met her those many weeks before.

Unable to paint, Edmond had hired Rosie Lehmann to help him finish the bank mural. Rosie—the talented painter and beautiful nude model. They would be spending a lot of time together, Mary thought despondently.

Even worse, Edmond wrote that he had resigned Mrs. Ensign’s commission, as she expected him to come in late July. His arm could not possibly mend by then, according to the doctor in Ishpeming.

For half a year, Mary had been planning for his return to Duluth. Now, because of her own stupidity, he would not be coming. It made her want to scream in frustration.

“Excuse me, dear.”

Mary started and looked up from the knitting in her lap. Emma Beach, the housekeeper, was standing in the library doorway.

“Yes, Emma?”

“You have two visitors. Mrs. McColley and Mrs. Larson.”

Mary’s former client had come calling, along with the woman who had been the focus of so much worry and effort during those days in Dillmont. Mary put her knitting down and jumped to her feet.

In the vestibule she found Clara McColley standing next to a stout lady with black hair going gray.

“Mrs. McColley,” she said, offering her hand, “how good to see you again.”

Clara McColley took Mary’s hand and shook it.

“And this must be Mrs. Olcott,” Mary said. “Finally we meet.”

The older woman scowled. “I’ll never use that name again. I’m having my attorney get me an annulment. Please, call me Mrs. Larson. And I am honored to finally meet my rescuer.” She offered her right hand and grasped Mary’s firmly.

Agnes Larson had a square, well-lined face that still showed the effects of fatigue and worry. But for the most part, she seemed to have weathered her ordeal quite well.

“Your heroics came just in the nick of time, Miss MacDougall,” said Clara McColley. “Some of the money from the company accounts is gone for good. But much remains untouched, and thank heavens the sale of the firm did not go through. We’ve put our old manager back in charge and we have great hopes.”

Mary smiled. Despite all the disasters in Dillmont, she had, in the end, been able to reunite mother and daughter, and save a well-respected enterprise.

“Mrs. Ol... Pardon me. Mrs. Larson. May I ask you a few questions?”

“Certainly.”

“How was Merton Olcott able to get you into Westerholm? Was it against your will?”

“Quite the contrary,” Mrs. Larson replied. “I confess now that I was suffering from severe melancholia for some time, ever since my real husband’s death. Merton suggested I needed professional help and I agreed to go to Westerholm, with the hope that their therapy would mend me. Merton insisted that we keep my committal secret, to prevent any rumors that might hurt Garlock & Larson. He said he would only tell my daughter and a few of the top men at the factory.”

She shook her head angrily. “Instead, he told them that I was dead, and he went about appropriating the company and its bank accounts.”

“Do you feel that Dr. Applegate acted properly, accepting your husband’s opinion of your problem?” Mary asked.

Mrs. Larson’s expression softened. “The doctor was horrified to learn that he had played a role, however innocent, in the fraud. But I do think he sincerely believed his diagnosis of my mental state was correct. He did not do what he did because my husband persuaded him to. He put me into Westerholm because he genuinely believed I would get better there. We had several long talks, and he helped me to realize that losing my husband could never be gotten over. Those wounds ache until your very last day.”

Mary thought of Dr. Applegate’s own losses. The two young children who died despite his best efforts to save them. The mute wife and mother who sits by the window day after day at Westerholm, waiting for her son and daughter to return. Mary regretted yet again how she had misjudged the doctor in her rush to make sense of things.

“We are made of our scars as much as we are made of our bones and muscles,” Mrs. Larson reflected. “But one must keep on living and loving the people who are still with us.” She looked at her daughter with transparent affection.

“And the death certificate?” Mary asked.

“Dr. Applegate never wrote or signed that death certificate,” answered Mrs. Larson. “He assured me of that before I left Westerholm.”

“The doctor didn’t know you or have any reason to trust you, Miss MacDougall,” explained Clara McColley. “He told Mother he wired Merton right after you brought up the death certificate. My stepfather promptly assured him that you were some unhinged flibbertigibbet who had become obsessed with Merton Olcott. He said you imagined the supposed death certificate.”

That, realized Mary, was why Dr. Applegate had left his office so quickly after she had visited him. He was rushing to the train station to send a telegram. And that was what brought Merton Olcott to Dillmont double-quick, to reassure and placate the ruffled physician.

“Probably Willis Flugum stole a blank certificate from Dr. Applegate’s office at Westerholm, and he or Merton forged it,” Mrs. Larson theorized. “That and the coincidence of poor Annie O’Toole’s death gave Merton exactly the conditions he needed to put the final touches on the fraud.”

“But now Mother is home, safe and sound,” Clara McColley said with a grateful smile. She reached into her purse and pulled out a small, folded piece of paper. “We’ve come to pay you for your services. Since we never received a bill, we could only guess at the figure. We decided on one thousand dollars, after all that you suffered for us. If it’s not enough, please say so.” And she held out the check.

Mary was frozen on the spot. She hadn’t even expected to receive a payment, after the fiasco she had presided over. Let alone such a large payment.

“You’re very kind,” she said, pointedly not taking the check. “But it was hardly a well-handled case. I made so many mistakes. I really don’t deserve any reward at all.”

“Mary?”

The three women turned as John MacDougall strode toward them through the foyer. He held a lit cigar in his right hand and wore an amused expression on his weathered face. He stepped into the vestibule, with Emma right behind him.

“If you’re to be a businesswoman, my girl, it doesn’t do to turn down payment from satisfied customers. Even if the job was a little slapdash.”

Mary beamed at him. Finally, a note of approval from her long-suffering father. “Thank you,” she said, taking the check from Clara McColley.

“Now ladies,” John MacDougall said, “if you’re not in any rush, may I invite you out to the porch in back for a cup of tea or coffee. I understand we have some fresh-made shortcake with strawberries. Emma, would you lead the way?”

* * *

AS MARY SAW HER TWO visitors out the front door an hour later, she noticed that the day’s last post had arrived and was sitting on the side table in the vestibule. Riffling through the items, she found a thin brown parcel from Ishpeming. She ripped it open and extracted a piece of cardboard wrapped in tissue paper. She pulled off the tissue and smiled.

There, mounted to the cardboard, was one of the al fresco portraits that Paul had made of Edmond and Mary. Smiling, Edmond leaned against one side of that old maple, his arms crossed, his gaze focused on Mary. She stood on the other side, her hat in hand, regarding him with equal fondness—as if the two of them were sharing some sweet secret. The memory of that morning came flooding back to Mary, in a bittersweet rush.

The accompanying note was from Paul. He wrote that he had wanted to get the photo mailed to Mary before he left for Pittsburgh, where he would be visiting Christena for a while. Well why not, Mary thought. Christena and Paul had found each other. Apart from saving Agnes Olcott, it was the only good thing to have come from this horrible holiday.

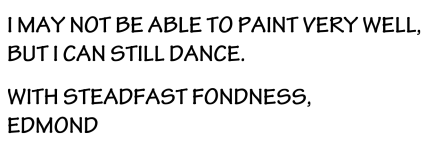

But there was one other item in the large envelope. A small tablet with a simple white card attached to it. On the card, in block letters, were written the words:

WHAT ON EARTH DID IT mean? Mary examined the tablet and then understood.

On each page, Edmond had drawn—obviously with his left hand—a bearded stick figure with his right arm in a sling. As Mary flipped through the tablet sheets with her thumb, the stick man danced a jolly little jig.

Relief washed over her like a wave. Edmond seemed to be saying that he had forgiven her. She put everything into the brown envelope, tucked it under her left arm, and headed back to her mittens.

Mary MacDougall the detective vowed she would live to detect again. And Mary MacDougall, ardent admirer of Edmond Roy, hoped that one day soon she would feel his strong arms twirling her around the dance floor.

—The End—