|  |

The Unfortunate and Mysterious

Disappearance of Jeanette Harrison

From the Papers of Jeanette Harrison Sauer

JANUARY 1902

If I had in my possession a time machine of the sort Mr. H. G. Wells writes about, I would climb into it, pull the lever backward until I reached the summer of 1900, climb out, track myself down, look me in the eye, and say, “You, Jeanette Harrison, are a total and complete dunce!”

My younger, less-enlightened self would surely take offense, but I would give her no time to reply.

“You are a partner in a somewhat profitable secretarial bureau. You own a modest but beautiful house in Benton Park, bought and paid for by the hard labor of your dearly departed Daniel. You have a small nest egg in a savings account at the bank, thanks to the generosity of your cousin Alice MacDougall, who so kindly remembered you in her will. For a 30-year-old widow, you are in a very good situation financially. And yet you plan to gamble all your reserves on some insane scheme suggested by a total stranger.”

“But I’m almost guaranteed to increase my money four-fold,” this naïve me would protest. “And I’d like to think I’m a good enough judge of human nature to know who I can and can’t trust.”

It almost makes me smile now, to think how self-confident I was back then. And to look at me now. Well, as the Good Book says, pride goeth before a fall, and fall I did. Right into the wretched hole from which I fear I may never climb out.

If only I could sleep. But the infernal noise won’t let me. I refer not only to the several working men next door snoring away like approaching thunder, but also the scrawny old woman in the swaybacked, spring-screeching bed next to mine. Where the men rumble, Gertie makes a din not unlike a dull saw hacking at tin. Poor thing—she has had a hard life. I shouldn’t begrudge her the little respite she has from it.

But because of her nocturnal racket, slumber and pleasant dreams escape me. When I drag myself out of my own sagging, decrepit bed at four in the morning, to bake the breakfast biscuits, I usually climb down the stairs bleary-eyed, foul-tempered, and a bit lame in the left leg.

And so I lie in bed all night, staring at the ceiling and going over and over again and again the chain of events that led me here, knowing that I have no one to blame but Jeanette Harrison for the state in which I find myself.

* * *

IT WAS A LOVELY JULY morning in 1900, a Tuesday as I recall. I was busily typing out my shorthand notes from a board meeting of a charitable organization that helps indigent folks around St. Louis. Our office was in a shabby old building on the fringes of downtown, up on the fourth floor, the top floor—where it got blastedly hot in the summer. But it was still not unpleasant by about ten. My partner had gone to visit another regular client, and the two girls who typed for us part-time weren’t expected in until after lunch.

I was banging away on my new Underwood, when I heard a rapping on the doorframe behind me.

“Hullo,” said a woman’s voice, a voice rich and melodious. “Excuse me.”

Rolling my secretary’s chair around 180 degrees, I caught sight of a middle-aged lady in a fancy gray dress, its collar and cuffs outlined in a lovely pink-colored piping. She had on a broad summer hat decorated with red feathers, and was a good deal shorter than me, and somewhat plump. A bit of perspiration glistened on her forehead, no doubt from climbing the stairs.

I hopped up from my chair. “Yes, ma’am. How may I help you?”

Removing her gloves, she stepped into the office and smiled at me—a lovely smile, as it happened. “I was told that I could find the Summit Typing Bureau at this location. But the sign says...” She turned and peered at the door, which was open and extending into the office. “...Antonio Di Cicco, Attorney at Law.”

“You’ll have to forgive us,” I said. “We just moved in a month ago and haven’t gotten around to getting Mr. Di Cicco’s name removed and our own painted on. At any rate, you’ve come to the right place. I’m Mrs. Harrison, one of the proprietors of the Summit Typing Bureau.”

I offered my hand to her. She shook it once or twice, with a light grip that Daniel would have called “tepid.” I noticed that she wore a rather gaudy diamond wedding ring.

“I am Mrs. Von Wassenburg and I am in need of someone who can type a dozen documents without so much as a single error.”

She looked at me, not in an unfriendly way, mind you, but somewhat imperiously. She seemed a woman who was used to getting her way. The name was German or Austrian, and she had a trace of an accent. But her English was quite good.

“No erasures, Mrs. Harrison. No corrections with pencil. They must be absolutely perfect. Is this something that you would care to undertake?”

Before I answered that question, I needed to ask a few of my own.

“Can you tell me, Mrs. Von Wassenburg, about the nature of the documents?” Then it struck me that there was no reason to continue our conversation standing by the open door. I gestured for her to follow me to my desk and she sat down there in the straight-backed oak chair.

“Well,” she said, putting her black beaded purse on my desk, “these will be copies of a brief prospectus that I wish to distribute among potential investors, in the form of a personal letter. May I tell you something in complete confidence?”

I nodded and said she could. The expression on her still-pretty face was one of satisfaction at her cleverness.

“I wish to create the impression that my husband and I are approaching each person purely as an individual. Each needs to think that he, or she, alone is being presented with this very fine opportunity. People like to think themselves special, you know, and this is a means of making that impression.”

It sounded like a good tactic to me. “So folks will be more inclined to make an investment in your business, thinking they are the first to come aboard?”

She nodded. “That is the effect one hopes for.”

“May I ask about the nature of your enterprise?”

She leaned toward me, as if she feared someone eavesdropping on us—though we were quite alone.

“Even as we speak, my husband is up in Alaska, where he has staked two claims a day’s hike up off the Yukon River, a few dozen miles east of St. Michael. I hope you understand, Mrs. Harrison, that I cannot tell you the exact locations.”

“Of course,” I said. Though why she thought I might have the means to dispatch claim-jumpers to Alaska in short order baffled me.

“We have resources of our own, Johann and I. But the cost in men, mules, and materiel to fully exploit these claims far exceeds what we can handle. So, while Johann is living rough up in Alaska, keeping an eye on things, I am visiting people I know in St. Louis, as well as in Chicago and Seattle. I am partway to getting the funds we need. Several more investors here would put us over the top.”

“Well,” I said, “good news indeed. I was under the impression, though, that the gold rush up north had waned.”

She chuckled. “Mrs. Harrison, as my husband discovered, the gold does not know that. The gold keeps no schedule. It waits patiently in the ground until someone with grit and perseverance comes along with a shovel and a mule. Here, look.”

She took her purse from the desk and reached into some pocket inside, searching. Withdrawing her clenched fist, she opened it, revealing a luminous yellow object about the size and shape of two peanut shells mashed together. She laid the object in my open palm.

I took a sharp intake of breath, realizing that the gold nugget in my hand represented many months of rent and food and clothing and books. It almost seemed to radiate warmth into my palm, like a little sun. The thing mesmerized me.

Mrs. Von Wassenburg beamed at me. “Beautiful, is it not?” And she was quite right. The gold nugget not only represented wealth and freedom, but was lovely to look at and to touch. I had never in my life held anything like it. Feeling a strange little pang of reluctance, I handed the lump of precious metal back to her.

“Yes, it is,” I said. “Now, can you tell me how long the document is that needs typing?”

“I can do better than that,” she answered, replacing the gold into its cavity in her purse. She pulled out a folded piece of foolscap and gave it to me.

Her gold-mining prospectus was written out in a loose, looping hand on the entire front side of the paper and part of the back. I estimated about eleven hundred words. There was some technical language in there, as well, that would require special care.

“How many copies will you need?”

“Six, to start with, Mrs. Harrison. To be delivered to me at the Planter’s Hotel. I will pay you in cash when you bring them.”

I told her how much her cost would be and she agreed instantly, handing me another, smaller sheet of paper with names and addresses on it. I recognized some of them as leading figures in St. Louis society; names I had seen many a time in the newspaper. Mrs. Von Wassenburg was nothing if not ambitious.

“I will send over the letterhead you are to use by courier,” she said, rising to her feet. “Well, this has been a pleasure. I will see you in...?”

“Day after tomorrow, I should say. At two o’clock, if you’ll be there.”

She said she would and we went out into the hallway. I could feel the day’s waxing heat coming deeper into the building. The thing most urgently needed for the office was an electric fan, but my partner was stubbornly resisting the extra expense.

“Let me walk you downstairs,” I said.

She shot me a glowing smile. “How kind of you, Mrs. Harrison.”

We started down, laughing and joking—quite pleased with ourselves. I jabbered away, making small talk about this and that, but my thoughts were with the nugget of gold and how wonderful it had felt in my hand.

If I had known at that moment what was to come, I would have taken the woman by her shoulders, shoved hard, and sent her tumbling down. To her death, I should have hoped.

* * *

THERE, AT THE BOTTOM of the stairs, I couldn’t get my mind off the feel of the gold nugget warming the palm of my hand. It had intoxicated me. Feeling the need for a treat, I ambled around the corner and bought a small package of chocolate candy from the confectionary. The owner there knows me well, chocolate being the one indulgence I cannot live without.

The rest of my day and the morning of the next day were devoted to a business meeting at an association of brewers in a fancy office building downtown. I took shorthand dictation in a rather palatial boardroom, then rushed back to the office to type it up for delivery bright and early on Wednesday.

I began on Mrs. Von Wassenburg’s prospectuses that afternoon, and had them done by mid-morning the day after, a Thursday. It made me proud that she would not be able to find the merest hint of an error in the six copies; each, of course, addressed to a different individual. There had been two or three mishaps, but she had provided plenty of stationery with which to begin anew. It was a rather sumptuous cotton rag paper of cream color, with “Von Wassenburg Mining” and a New York City address printed on top in an elegant script. Even the watermark said “Von Wassenburg.”

By the time I finished, I had almost committed the details of the Von Wassenburgs’ prospectus to memory. It quoted the assays carried out at the two mining sites, which seemed most encouraging. It listed the costs in men and materiel needed to fully exploit the finds. It laid out a schedule for operations, once complete funding was secured. And it proffered a purchase of ten shares at a minimum at a cost of one thousand dollars per share. The Von Wassenburgs estimated that any investor getting in on the ground floor of the mining venture would at least triple his investment in a matter of two or three years.

The very idea of making so much money so quickly practically made my head spin. Stupidly, I began to wonder if I could raise ten thousand dollars to put into the enterprise—that is, if Mrs. Von Wassenburg would have me. The gold nugget still held me in its thrall and I felt eager to try my hand at making a small fortune. I hate to admit it, but I had become a little feverish, a little greedy.

I had just about finished the last prospectus, addressed to a leading philanthropist of the city, when I stood to stretch—sitting too long causes my left knee to stiffen sometimes. I went over to the window.

“Are you almost done with those letters, then, Jeanette?”

I turned around and saw my business partner, Mrs. Ruth Gardiner, standing just inside the door, putting her hat atop the coat rack. She was a tall, thin woman with a narrow face that looked rather severe in repose. But, in fact, she laughed a lot and very much enjoyed a good joke. We had both done typing from our homes and were introduced to each other by our Underwood dealer.

“Almost, Ruthie,” I answered, stretching my arms up in the air. “I’m taking them to the client’s hotel just after lunch. I promised them to her by two.”

“What’s the job about?” She came over to my desk and peeked down at the little pile of Von Wassenburg stationery.

“A kind of prospectus for investing in a gold mine up in Alaska.”

“My goodness,” she said, bending down for a closer look at the letterhead. “Does this have something to do with the Baroness Von Wassenburg?”

I gave her a surprised look. “Well, I just know her as Mrs. Von Wassenburg. Is she some sort of nobility?”

Ruthie put her hands on her hips and gazed at me rather sternly. “You don’t read the society pages, do you? The baroness has been written up several times during her visit to St. Louis. She’s quite the thing, apparently.”

“If you’d like, you can tag along when I deliver the prospectuses.”

“May I?” Ruthie asked, sounding a little giddy. “I’ve never met a baroness before.”

“Until the other day,” I confessed, “neither had I.”

Ruthie and I arrived at the Planter’s Hotel on North Pine a bit before two and made our way through the grand lobby to the elevator, and up to the sixth floor. We were greeted at the door of the baroness’s suite by a slender, dark-haired young man who introduced himself as her son, Kurt Von Wassenburg.

Whether he was the heir to the title, I had no idea. I only know that he had dancing brown eyes and a very friendly manner. He asked us to seat ourselves and wondered if we would like to have some tea and chocolate while we waited for his mother, who was in another room with one of her potential investors.

Of course, I could not turn down the offer and helped myself to the most delicious chocolate creams I had ever tasted, imported, I was told, from Switzerland.

Mr. Von Wassenburg was perfectly delightful, an amiable conversationalist who managed to make two somewhat older ladies feel like the center of the world. He asked about our business and where we were from and about our families. He seemed especially interested to know that I was related to John MacDougall. I’m afraid I was guilty of name-dropping of the most shameless kind. I hadn’t seen John in some time, but I so wanted to impress our host with the fact that I, too, had connections to the exalted world of high finance.

“The mining magnate John MacDougall is your relative?” he asked, sounding very impressed.

“Oh, yes,” I replied. “John was married to my lovely cousin Alice, who unfortunately passed away several years ago. But I regularly correspond with his daughter, Mary, who is of course my first cousin, once removed.”

You could almost see the glint in the young man’s eyes. “I imagine Mr. MacDougall has more money than he knows what to do with,” he said, in a German accent that seemed oddly thicker than his mother’s. “If you are so inclined, please let him know about the Von Wassenburg mines. A sure way to turn ten thousand or twenty thousand into sixty or eighty thousand. You might even consider investing yourself, Mrs. Harrison. It takes only ten thousand.”

Even though I had thought about it, when he said it, it sounded absurd. “If only I had that sort of money to gamble.”

“Ah, but it is no gamble, Mrs. Harrison,” the handsome aristocrat declared. “It is practically a sure thing. My father is staking the family honor on it.”

Just then Ruthie leaned toward me—we were sitting next to each other on a fancy maroon velvet sofa—and whispered in my ear. “Perhaps we could go in together. That way neither of us would have to risk as much.”

Ten thousand dollars is an awful lot of money. Still, Ruthie’s idea suddenly sounded feasible. My little house was paid for, but I supposed I could take a mortgage on it and extract some money. I had a tidy amount in the bank, as well.

I see now what a chuckleheaded fool I was. Having fallen in thrall to the Von Wassenburgs’ charm, I began to think it quite reasonable to cash in my assets for this wonderful investment.

It was so intoxicating, being there in an opulent suite with a handsome young man who was plying us with chocolates and compliments. It was a milieu that seemed somehow within reach, once I had bought shares in the Von Wassenburg mines and tripled my investment. I suddenly could envision myself as a woman of independent means, booking grand accommodations at the Palmer House the next time I visited Chicago.

In the midst of my daydream, a door across the room swung open and out came the baroness and her visitor, an older gentleman. When she introduced him, I sucked in my breath. His name was immediately recognizable. He was a retired banker and one of the city’s most noted philanthropists. It was exciting just to be in the man’s presence. The baroness certainly had impressive connections. I had no doubt the banker would be one of the larger shareholders in her husband’s mining venture.

“Ah, Mrs. Harrison,” the baroness said, after she had shown the gentleman out. “Right on time. You have my letters?”

I said that I did, and handed her the folder. She flipped it open and leafed through the pages.

“It all looks in order.” She turned to her son. “Kurt, will you give Mrs. Harrison her money. Twelve dollars, I believe it was?”

While Kurt, as he insisted we call him, went for my payment, I introduced Ruthie to the baroness. When her son returned, he handed me the money, then whispered in his mother’s ear. She looked at us and her face brightened.

“My son tells me, ladies, that you yourselves might have some interest in taking part in our little enterprise. Is that right?”

I felt a bit intoxicated, and so, apparently, did Ruthie. We nodded and said that we did, but that it might take a little time to gather our finances.

“Well, we have sold about half of the shares that we are prepared to offer,” the baroness said with a satisfied smile. “And I expect the rest will go quickly, once we distribute these beautifully typed prospectuses. So if you really mean to invest, my dear ladies, you must not dally.”

And so began what would eventually become the train wreck of my brief career as a financial speculator.

* * *

AFTER RUTHIE AND I left the baroness’s suite, we immediately began to make our plans. She would need to discuss the investment with her husband over the weekend and hoped to put together perhaps two or three thousand dollars.

I, on the other hand, was free to do whatever I wished with my money. That, at least, is an advantage of being a widow.

I spent Saturday morning with pencil and paper, calculating what I might do with the money we would make from our investment. I intended to earmark some for our business, with the hope of expanding the number of customers we could service by hiring full-time help. And of course I would use some of the money to travel. I had been to Chicago several times, but never to New York. I wondered how much a journey to London and Paris would cost.

My head was still in the clouds when the doorbell rang and a messenger handed me a letter. It was an invitation from Kurt Von Wassenburg to join him that evening for dinner. His mother was otherwise occupied so we would be dining alone in the fine restaurant at the Planter’s Hotel. Naturally, I sent the messenger back with a positive reply. How excited I felt!

I spent the afternoon deciding what to wear. I did not have many party costumes, but I did find a dress that I had worn occasionally when Daniel was still alive. He always said it highlighted my best attributes. He very much appreciated my figure, which needs no corset to achieve the desired shape. Looking in the mirror at myself, I was pleased to see that it still fit me perfectly. I might even have hoped to turn a few heads as I came into the dining room.

Kurt evidently agreed with my assessment, as he greeted me with an intake of breath and an admiring look up and down. “Jeanette,” he said, “I barely recognized you. You light up the room in that dress.”

The evening continued on in that vein. Courses and drinks mixed in with conversation and flirtation. I was very flattered by Kurt’s attention. Caught up in the gaiety of the evening, I’m afraid I drank a wee bit too much. That’s why I was so free with the information I gave him about John MacDougall and his daughter. I am ashamed to admit that I even told him exactly what street they lived on up in Duluth, and where their apartment was in St. Paul, Minnesota.

“I expect that a young woman with Mary’s wealth has to fight off potential suitors,” he observed.

“I should imagine so,” I remember saying over my third or fourth glass of wine. “She is quite lovely, although I don’t think she realizes it. There’s something of the tomboy about her.”

From there the conversation went on to travel and theater, of which the man was quite a connoisseur. While he certainly could have taken advantage of me later that evening, Kurt acted the perfect gentleman, sending me home in a hansom cab and vowing to see me again soon. When I woke up the next morning, my head was aching. It wasn’t until afternoon and a few cups of good strong coffee that I was again able to go over the figures I had come up with regarding my shares of the gold mine venture. I was anxious to hear what Ruthie thought she could scrape together.

But Monday morning, as soon as I returned to the office from a meeting for which I had taken shorthand notes, Ruthie took me aside, so that our two part-time girls couldn’t overhear us. She looked crestfallen.

“I’m so sorry, Jeanette, but Philip says no. He is quite sure that the baroness is on the up and up, keeping company with...” And she said the name of the retired banker whom we had seen in the baroness’s suite. “But two or three thousand is an awful lot of money to risk on a gold mine venture in far-away Alaska. It took us a lot of sweat and quite a few years to get comfortable again after the last depression. Philip doesn’t want to speculate with our hard-earned money. I’m sorry, Jeanette. So sorry.”

I had calculated what I could bring to the table. A new mortgage on my house in the amount of four thousand dollars might be possible and my savings account of two thousand would bring the amount up to six thousand—still four thousand short. There was my equity in the typing agency. But I was reluctant to draw upon that—even if Ruthie was willing to buy some or all of it.

It so happened over the next few days I was able to secure commitments for three thousand dollars from several of my friends. But, of course, that still left me a thousand short. My dream of making a killing in Alaskan gold was not to be. That was when I received a message from Baroness Von Wassenburg that she needed more copies of her prospectus letter, and could I please do them quickly?

When I delivered them, I found her having tea by herself. I was disappointed Kurt wasn’t there. I had rather hoped to see him again, and would not have said no if he had asked me to dinner a second time. I confess that I had so enjoyed spending those hours in the company of such a handsome young man.

The baroness took the newly typed letters and paged through them, examining each sheet carefully. “Your work is quite excellent, Mrs. Harrison. You would not believe the trouble we have had from typists in other cities. I am so much in your debt.”

Startled by her generous praise, I thanked her profusely and wondered if, perhaps, she might write a brief testimonial on behalf of the Summit Typing Bureau. She said she would be happy to and would mail it to me.

I thanked her one more time, and started to leave.

And, oh, how agreeable my life would have been if I had just kept walking!

But I turned back. “I had hoped to raise the ten thousand you require, Baroness. But I am afraid I haven’t been able to do so.”

From her chair, she gave me a look of what almost seemed motherly concern. “I am so sorry to hear it, Mrs. Harrison. We are almost entirely subscribed and another two or three investors is all that we need.”

I mustered up the happiest smile I could. “I hope your husband strikes a very rich vein, and that all your investors reap handsome benefits. Please give my regards to your son.” I then turned to leave.

“Just a moment.”

I faced the woman again, wondering what she wanted.

“How much can you invest, then?”

“I don’t have it in hand, but I’m certain I could raise nine thousand.”

She motioned me to sit in the chair opposite hers. Putting her hand to her chin, she regarded me in an almost affectionate way. I could tell that in her younger days, she must have been quite a beauty.

“Now this is just between the two of us,” she said, practically in a whisper. “I have made no exceptions for anyone else. But in your case, because you have been so helpful to us, I would be happy to take an investment of nine thousand dollars. That will get you nine shares in Von Wassenburg Mining.”

For a second, I almost felt the room spin. My delight at her acceptance was suddenly overshadowed by the realization of what I was agreeing to. I would be committing every cent of cash I had to this enterprise—and the hard-earned money of my friends. I told her it would take me a few days to get the money and bring it to her in the form of a cashier’s check. Then I steeled myself for what I needed to do.

“Nine thousand dollars is an awful lot of money,” I said with a certain timorousness.

“Indeed, it is,” the baroness agreed.

“Before I collect the funds, may I ask if you possess any references that I might review?” I was almost afraid she would call me an ungrateful wretch and throw me out.

“Very sensible of you to ask,” she said. “And we have such documentation for our investors. If you will wait here, I shall fetch the material.”

The portfolio she handed me contained letters from bankers in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, London, Berlin, and Munich that confirmed the probity and creditworthiness of the baron and baroness—though, of course, I could not read what the German bankers said. There were testimonials from earlier business partners. There were clippings from newspapers about the couple’s mining venture. Several letters recounted how pleased their authors had been to invest in an earlier enterprise involving a railroad. There was a document in German describing the noble lineage of the Von Wassenburgs, with an English translation.

It was all very impressive and reassuring. And I remembered having met the prominent retired banker in this very room just a few short days ago. More than anything, his involvement convinced me to take the plunge and invest in the gold mines. For if such a distinguished gentleman was doing business with the baroness, was that not a ringing endorsement of the investment’s safety?

Convinced of her trustworthiness, I handed the portfolio back to her. Then I asked her a little favor.

“May I see the gold nugget again, Baroness?”

She smiled and laughed. “Of course.”

Like a damned fool, I stood there wearing a stupid grin, fondling in my hand the very instrument of my own destruction. But the little thing was so lovely, so smooth, so warm, so seductive, that I held no thought in my head of doing anything but moving forward.

* * *

WHEN I PRESENTED THE baroness with the cashier’s check the next week, she sent Kurt down to the hotel offices to fetch the bookkeeper, who happened to also be a notary. While we waited, she took a blank certificate of stock ownership for Von Wassenburg Mining and filled in my name, my address, and the number of shares that I had purchased. She signed and dated the form, and when the bookkeeper arrived, he notarized it.

“Now before you go,” the baroness said, “I am going to provide you with the information that you will need in exercising your ownership of this investment. How to contact Von Wassenburg Mining. As well as our own personal addresses in New York, London, and Munich. In the event that you wish to sell your shares, instructions are provided. We, meaning Von Wassenburg Mining, ask only that we be provided with the right of first refusal.”

“Meaning,” I said, “that I first offer to sell the shares back to you?”

“Correct. You will receive quarterly reports on the progress of the mines and, God willing, in two or so years you will begin to receive annual dividend checks. And that is not counting the appreciation of the value of your shares.”

On a blank sheet of the same letterhead that she had given me to type her prospectuses, she wrote down her various addresses and brief instructions for selling the stock. She also asked for the addresses of my business and my home.

I shook the woman’s hand and started to leave. But before I was out the door, Kurt took me aside and asked if I would again do him the honor of dining with him some evening next week. I said of course, it sounded wonderful. He said he would send a note with the date and place.

I can tell you, I left the hotel walking on a cloud. Confident in the knowledge that I was quite the canny investor to have hitched my wagon to the Von Wassenburgs, and giddy at the prospect of another evening with Kurt. It was not until the weekend that I realized I had forgotten another, far smaller financial transaction involving the baroness: I had neglected to collect the twelve dollars that she owed me for the second batch of letters.

My work the following Monday required me to be a few blocks from the Planter’s Hotel, so I decided to stop and collect my small debt. The hotel elevator was not in operation, due to a mechanical fault. So, huffing and puffing, I mounted the six flights of stairs and found myself at the door to the baroness’s suite. It was open and a maid’s cart, full of its linens and supplies, was parked in the hallway. I rapped lightly on the doorframe and the maid appeared. She was a young black woman.

“Yes, ma’am?” she said. “How can I help you?”

“I just came to call on the Baroness Von Wassenburg. I have some business I need to conduct with her. If she isn’t here, perhaps her son could help me.”

Thinking back on it, the maid’s reaction was almost comical. Her expression gyrated between amusement and discomfort, in equal measure; as if she didn’t know quite what to say.

“Is there a problem?” I asked.

She raised her eyebrows. “Guess you could say that, ma’am.”

“What is it? Has the baroness taken ill?”

She looked up and down the hallway. “You won’t tell anyone I told you, will you?”

I shook my head. “Of course not.”

“Well, yesterday a gentleman comes here with a policeman...”

I could feel my blood beginning to go cold.

“But the room was empty. Everyone had skedaddled.”

“Why did the police want to talk to the Von Wassenburgs?” I asked apprehensively.

“They found out the son and mother—only she isn’t his mother—are some kind of swindlers getting thousands of dollars off of rich white folks.”

Then she saw my ashen face and looked embarrassed, as though she sensed my situation.

“Sorry, ma’am, I didn’t mean any offense.”

“No offense taken,” I mumbled. “You say the baroness is not Kurt’s mother?”

She shook her head. “No. They say he’s her lover. And she’s sure not royalty. She’s from New York City.”

My knees nearly buckled.

“And has anyone seen the baroness...the woman?”

“Not since yesterday morning,” the maid said, shaking her head. “She still owes the hotel for two weeks of accommodation.”

As you can imagine, I left the place in a daze. For several minutes, I leaned against a light pole, shaking my head and repeating, “Stupid woman, stupid woman.”

I finally remembered the banker I had seen in the hotel room. The one whose involvement had clinched the deal for me. Surely he could offer some advice on what to do. He probably already had his lawyers working on getting his money back.

The financial institution he founded was five blocks away. I ran as fast as I could down the street, no doubt alarming several other pedestrians along the way. I was panting by the time I climbed the steps. I immediately went to the first desk I saw and asked if the banker perhaps still kept an office there. “Why, yes he does,” the skinny, bespectacled clerk said. “But I’m afraid he spends his summers up at his lake cottage in Wisconsin.” He then nodded up at a portrait hanging on the wall.

A gold plate attached to the frame identified the subject as the founder of the bank. He was a very distinguished gentleman, but in no way did he resemble the man to whom the baroness had introduced me. I almost laughed out loud. Jeanette Harrison was living proof of that famous P.T. Barnum dictum—there is a sucker born every minute. And I certainly was one of them.

Instead of taking the streetcar back to the office, I simply wandered on foot. For hours and hours. Along the way, I stopped at a tavern and fortified myself with two brandies. When I finally walked into the office at about five that afternoon, Ruthie and the two girls rushed to me, wondering where I had been. I was far too mortified to speak in front of the young women, but I took my partner aside and told her.

She had the look of someone who had just felt a bullet whiz by her left ear, and hit the person right behind. That would, of course, be me.

* * *

I WENT TO THE POLICE, who took down my information, but could do nothing more than to promise to keep me informed. The detective I spoke with said they hoped to recover the tens of thousands taken by the “Von Wassenburgs.” But he did not sound encouraging.

Bit by bit, the facts of the swindle came out in a series of newspaper articles. The baroness was known by several aliases—Jane Smithson, Serena Kotlikoff, Hilda Potter. Her so-called “son” Kurt was revealed to be an actor from Baltimore, Richard Prudhomme. The real Baron and Baroness Von Wassenburg did live in Munich, but neither of them had ever set foot on the North American continent. And there was no one up in Alaska wresting gold from the earth on behalf of them or the criminals who impersonated them.

With the enormity of the debacle spread out before me, I realized that the first thing I needed to do was pay back the good friends who had gone in for the last three thousand dollars. Since I had only a few hundred left in my bank account, I offered to sell my part of the bureau to Ruthie, and she accepted. Suddenly, I was an employee at the business I had co-founded and the owner of a house with a full mortgage. I went to work, aiming to climb up out of the hole I’d dug for myself.

What bothered me almost as much as losing my entire fortune, such as it was, was the thought that I had divulged so much information about John and Mary MacDougall to the shady man I thought was Kurt Von Wassenburg. Fortunately, John MacDougall was a canny man of business—I didn’t for a second think that he could be drawn into any dubious scheme.

But Mary was but a child, not yet twenty years old. She always struck me as a levelheaded girl. But in the presence of an attractive, suave older gentleman, I don’t know how susceptible she might be. I wrote to the MacDougalls regularly, as I always had done. But I did not have the courage to reveal what had happened, even though they ought to be warned. I was too big a coward.

So the days went on. Every night, as I sat alone in my little house, I would have a glass of brandy or gin. It had been my refuge after Daniel died and I believed I could control it. Later on it was two or three glasses. Sometimes I would run dry and walk to the tavern a block away.

The months dragged by. I began to get to work late, as I slept off my liquor. Eventually I stopped going and rather quickly lost the house to the bank. I stayed in cheap boarding houses for a while, and spent many a night sitting in a train station to save money. I nearly froze my hands and feet some of those cold winter evenings and days. It was only good luck that saved me from harm on two or three occasions.

I was fortunate to talk to a man in a tavern who lived at a boarding house in a rough part of town, run by his sister. They needed someone to cook and clean and would offer room, board, and a few dollars a week. I agreed and ended up working harder than I ever have in my entire life. But I have managed to stop drinking, though it’s still awfully tempting, I can tell you, to disappear into a bottle of brandy. Apart from death, it is the ultimate escape.

My friends no doubt wonder where I have gone, and why. I just cannot face them. I haven’t written to the MacDougalls in quite some time now. Occasionally on my one evening off a week, I walk down to my old business, the one now owned by Ruthie Gardiner. I look up at those windows high above the street. I never see Ruthie—I always make sure it’s well past closing time. And I let memories of better days flood over me.

I am content with my lot in life, which is of my own making. I am strong and I will survive. Sleep may be elusive, with old Gertie snoring the night away. But when I do fall asleep, I can still dream. And one thing I dream about is getting my hands around the throat of the “baroness.” And squeezing. Squeezing. Squeezing.

Postscript

June 1902

I started writing this account some months ago to explain what had happened to me, in the event I died without giving witness. But it seems the tale is not quite over.

I had made another of my evening visits to my old business a month ago, on a beautiful May day. I had started the long walk home, pausing to look in a window that displayed lovely ladies’ dresses, when I noticed someone across the street.

He was a slouching, shifty fellow standing in a store entrance, watching me. Clearly watching me. I had never seen him before. And as I started walking, he started walking, too. When I stopped, he stopped. Why was he stalking me?

I made my way home, using side streets and back alleys, assured that I had given him the slip. But a few mornings later, as I set out to run some errands for the landlady, I saw him again. He clung to me like a shadow as I went from store to store, then dropped out of sight as I came back home.

It troubled me a bit. But I figured that if he were going to attack me, he would have found better circumstances. And if he was intending to perpetrate some kind of scam on me—well, good luck to him. I had nothing to lose, as I already had lost it all.

I didn’t see him again for several weeks. But just this morning, as I was helping to clean up the breakfast dishes, a knock came on the door. After a few moments, my employer came out to the kitchen. “Mrs. Harrison,” she said in a disapproving tone, “you have a visitor. Whatever he wants, be quick. We have all the bedding to wash this morning.”

I went into the parlor where my slouching, shifty shadow was waiting. By now I was more curious than afraid. What on earth did the man want of me?

“Mrs. Harrison?” he asked, giving me a thorough examination from top to bottom. He stood before me, hat in hand.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Mrs. Jeanette Harrison?”

“That’s me. What do you want?”

He looked a little amused at my irritation. “I am here on behalf of John MacDougall. He hired the detective agency that employs me to track you down, seeing as how you vanished, for all practical purposes.”

“Oh,” was all I could manage to say.

“I have notified Mr. MacDougall about your troubles and present situation, and he would like to help.”

“He would?”

“Mr. MacDougall has authorized me to offer you the job of personal secretary to his daughter.” The slouching detective thrust a white envelope at me. “This here is an open train ticket to Duluth and cash money to cover your expenses on the trip. The letter in the envelope explains the terms of your employment and your wages. He says you are to notify him of your decision as soon as is practicable.”

The look on his face said I would be a damned fool to say no.

* * *

AND SO I WILL BEGIN anew. Duluth is a charming town, as I recall from my earlier visits. After the turmoil of these last few years, handling social correspondence and appointments for my sweet young cousin Mary will seem quite refreshing.

Mary has a good head on her shoulders and all kinds of interests, one of which, by now, will no doubt be finding a suitable husband and starting her family. I can well picture myself as the sedate companion who will help her along that path. What a quiet, tranquil life it will be.

If you enjoyed A Daughter’s Doubt...please take a few moments to write a brief review of it on Amazon, Goodreads, or wherever else you might post your opinions. Even a few words or a single sentence would be very much appreciated.

Acknowledgements

This book was made much better by the valuable insights and suggestions of my editors, beta readers, and proofreaders. Once again, my thanks go to Marlo Garnsworthy, Kate Collins, Jeri Smith, Marie Joseph, and Sue Wichmann.

––––––––

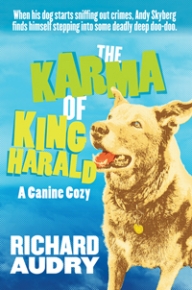

About the Author

RICHARD AUDRY IS THE pen name of D. R. Martin. As Richard Audry, he writes the Mary MacDougall historical mystery series and the King Harald Canine Cozy series. Under his own name, he has written the Johnny Graphic middle-grade ghost adventure series, the Marta Hjelm mystery Smoking Ruin, and two books of literary commentary: Travis McGee & Me and Four Science Fiction Masters. You can follow D. R. at drmartinbooks.com or on Facebook.

Be sure to check out Richard Audry’s other exciting mysteries at drmartinbooks.com and e-book sellers everywhere.

––––––––

––––––––

––––––––

––––––––