A

Polyurethanes

Introduction

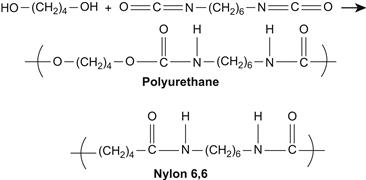

Polyurethanes are widely used in medical devices such as pacemakers, artificial hearts, and other blood contacting applications. Their excellent mechanical properties, stability, and good biocompatibility give them a special place in medicine. Polyurethanes were developed in the 1930s. Around this time, Nylon 6,6 – a condensation polymer of hexamethylenediamine and adipic acid – was developed and patented by Du Pont. This polymer achieved commercial success due to its good mechanical properties and fiber-producing ability. German scientists led by Otto Bayer began to explore new polymerization techniques in the hope of creating a material competitive with nylon. Initial work reacted difunctional isocyanates and amines to produce polyureas; however, these materials were too hydrophilic to be used as plastics or textiles. Diisocyanates were also reacted with diols to produce polyurethanes. One nylon-like polyurethane produced through the reaction of 1,4-butanediol and hexamethylene diisocyanate, as shown in Figure A.1, was used commercially in Germany. Chemically the polymer is the same as nylon except for the two additional oxygens per repeat unit, and the properties are similar except that the polyurethane has a lower melting point. These early polyurethanes also had lower water absorption, and better electrical and mechanical stability upon aging compared to nylon. Subsequently block polymers including polyester or polyether polyols were developed both in Germany and the United States.

FIGURE A.1 Synthesis scheme of a polyurethane through the condensation of 1,4-butanediol and hexamethylene diisocyanate. The repeat unit of the PU and of Nylon 6,6 are presented for comparison.

Today, polyurethanes (PUs) are a class of polymer which has achieved industrial relevance due to their tough and elastomeric properties, and good fatigue resistance. PUs are used as adhesives, coatings, sealants, rigid and flexible foams, and textile fibers. Furthermore, PUs have also been employed in biomaterial applications such as artificial pacemaker lead insulation, catheters, vascular grafts, heart assist balloon pumps, artificial heart bladders, and wound dressings.

Anatomy of a Polyurethane Molecule

The polyurethane molecule presented in Figure A.1 has a very simple architecture. Most commercially relevant PUs today are actually block copolymers (as seen in Chapter I.2.2, Figure I.2.2.4) meaning there are alternating segments in the polymer molecules composed of solely “A” or “B” repeat units. Furthermore, the materials are designed so that one of the segments – called the hard segment – is glassy or crystalline at the use temperature, while the other segment – referred to as the soft segment – is rubbery. If the monomers are appropriately selected, the hard and soft segments of the polyurethane will be incompatible, leading to phase separation and meaning that the composition of the bulk polymer will not be homogeneous. Instead, there will be nanometer-sized regions which are rich in hard segments, and other regions rich in soft segments. The unique block copolymer structure and phase separation of PUs results in unique and useful properties. One can consider the hard phase domains as providing highly efficient reinforcing microdomains which give rise to the unusual and very attractive properties of polyurethanes, such as strength and toughness.

The Physical Properties of Polyurethanes

Most polymer elastomers – such as rubber bands – are produced by lightly cross-linking a low Tg polymer into a loose network. When such a material is strained, the segments between cross-links can deform and elongate; however, when the load is removed the cross-links result in the material returning to its original form. Although these elastomers are useful, they are thermosets. Since the material is essentially one large molecule it cannot be dissolved, neither can it be made to flow through the introduction of heat and pressure. This means that once a thermoset elastomer is formed, it cannot be processed further. However, the unique segmented structure of PUs allows thermoplastic elastomers to be formed. When such materials are strained, the polymer segments in the soft phase will deform and elongate, while the hard phase will stabilize the structure, resulting in the recovery of the original form once the load is removed. However, unlike the covalent cross-links in thermosets, the physical cross-links present between hard segments can be undermined through the application of heat, and then reformed upon cooling, allowing the useful properties of elastomers to be combined with the simple processing procedures of thermoplastics. In addition to elastomeric properties, PUs have several useful interfacial characteristics. Foremost, PUs are abrasion- and impact-resistant, making them useful as coatings, and the materials also have good blood-contacting properties, making them useful in biomaterial applications.

Polyurethane Synthesis

The Precursors

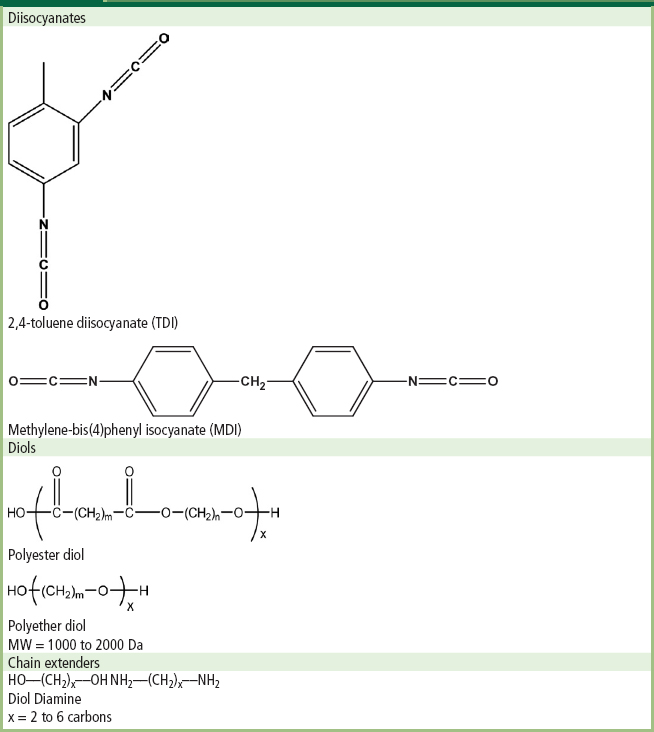

When synthesizing most PU block copolymers a two-step synthesis strategy is employed which involves three precursor molecules: diisocyanates; diols; and chain extenders. In the final polymer molecule the diisocyanates and chain extenders will form the hard segments, while the diols form the soft segments. Table A.1 illustrates the chemical structure of molecules often used to synthesize PU block copolymers.

TABLE A.1 Chemical Structure of Common Precursors used in Polyurethane Block Copolymer Synthesis: Diisocyanates, Chain Extenders, and Polyester or Polyether Diols

The diisocyanate molecules used in polyurethane synthesis can be aliphatic (such as Figure A.1), but most often aromatics are used (Table A.1). The two most commonly used diisocyanates employed in PU synthesis are 2,4-toluene diisocyanate (TDI) and methylene-bis(4)phenyl isocyanate (MDI). The soft segments are formed from polyether or polyester diols (sometimes referred to as polyols). These molecules have a molecular weight of 1000 to 2000 Da, and are well above their Tgs and melting points at use conditions, which impart a rubbery character to the resulting polyurethane. The last precursor is the chain extender. These molecules are often short aliphatic diols or diamines containing 2 to 6 carbon atoms, and are used to build the polymer up to its final high molecular weight.

Synthesis Reactions

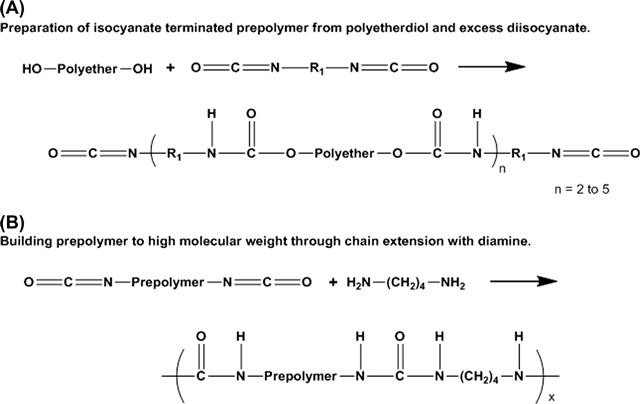

The isocyanate group contains two unsaturated bonds and is a highly reactive moiety. When reacted with a hydroxyl group, the result is a urethane bond, as illustrated in Figure A.1. The first step in PU synthesis reacts the diisocyanates with the polyether or polyester diols. Excess diisocyanate is used to ensure the resulting materials are end terminated with isocyanate groups, as seen in Figure A.2A. The result of this reaction is a prepolymer with a degree of polymerization commonly between 2 and 5. Next, the prepolymer is further reacted with the chain extenders to produce high molecular weight polyurethane molecules, as shown in Figure A.2B.

FIGURE A.2 Two-step synthesis of a polyurethane block copolymer: (A) Isocyanate-terminated prepolymer synthesis from excess diisocyanate and polyether diol; (B) Reaction of prepolymer with diamines to build high molecular weight polyurethane chains.

Tailoring Polyurethane Behavior

Many of the techniques described in Chapter I.2.2 to modulate polymer properties can easily be applied to polyurethanes. For instance, monomers with functionality greater than two can be used in order to produce cross-linked polymer structures. Also, as the cross-link density in thermosets controls material stiffness, the relative amounts of hard and soft segments in the PU can vary the modulus. Also, the length and chemical nature of the soft segment can be adjusted to further tune physical behavior.

For biostable biomaterial applications, MDI is generally used to form the hard segments, and polyether diols are often preferred to form the soft segments since they are more resistant to hydrolytic degradation than polyesters. However, PUs have been explored more recently as scaffolds for tissue engineering. For these applications, biodegradable PUs are required, the degradation rate must be controlled, and the degradation products need to be non-toxic. Soft segment structure is often used to build in the appropriate degradability. For instance, soft segments containing polylactide, polyglycolide, and polycaprolactone have been investigated, all of which are susceptible to degradation and the degradation rates vary based on chemical composition. The aromatic diisocyanates can result in carcinogenic degradation products; therefore, PUs for tissue engineering applications require the use of diisocyanates other than MDI and TDI. New PU formulations have been synthesized using lysine-diisocyanate, hexamethylene diisocyanate, and 1,4 diisocyanatobutane which are believed to degrade into non-toxic products.

Case Study What Problem was Addressed?

An individual may require an artificial pacemaker to regulate their heartbeat. The pacemaker is an implanted device which monitors heartbeat and provides electrical stimulation to the muscles of the heart, resulting in muscle contraction when needed. The pacemaker is connected to the appropriate heart muscles through pacemaker leads, electrically conductive wires which are fed to the heart through the vasculature.

The pacemaker leads require insulation. Initially poly(dimethyl siloxane) (PDMS) or polyethylene was used as the insulator for the leads. However, both of these materials resulted in a fibrous endocardial reaction. Furthermore, PDMS has a low tensile modulus and poor tear resistance.

What properties were required of the biomaterial?

A successful insulator for pacemaker leads would not elicit a fibrous reaction from the heart, and would have high tensile strength and resistance to tearing allowing for thinner lead insulations to be produced.

What polymeric biomaterial is used?

In 1978 polyurethane was introduced as a lead insulator. Although not as flexible as PDMS, the PU had superior tensile properties and tear resistance. This allowed much thinner lead insulations to be fabricated without compromising handling properties. The thinner insulation allows multiple leads to be inserted per vein, enabling sequential pacing. Furthermore, the PU surface has lower friction in contact with blood and tissue than the PDMS surface, allowing easier insertion of the leads.

The search for the optimum lead insulation material is not over yet, however. In the 1980s it was found that metal-induced oxidation from lead metals resulted in undesired degradation of the polyurethane insulation. Lower ether content in the polyurethane was one solution to this problem, although this results in higher modulus insulation. In subsequent years there have been changes in the material used for the lead wire, and silicone rubber remains in use as well as polyurethanes for pacemaker insulation. Research is underway to find more biostable polyurethanes for this application.

Concluding Remarks

Polyurethanes are a unique family of polymers with interesting properties which arise from their block copolymer nature and the resulting phase separation. These materials have achieved industrial success in everyday applications, as well as in the biomaterials field.

Bibliography

1. Billmeyer Jr FW. Textbook of Polymer Science. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience; 1984.

2. Brandrup J, Immergut EH, Grukle EA. Polymer Handbook. 4th ed. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience; 1999.

3. Dumitriu S. Polymeric Biomaterials. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker Inc; 2002.

4. Lamba NMK, Woodhouse KA, Cooper SL. Polyurethanes in Biomedical Applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1998.

5. Mahapatro A, Kulshrestha A. Polymers for Biomedical Applications. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK: American Chemical Society Publication; 2008.

6. Randall D, Lee S. The Polyurethanes Book. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2002.

7. Rodriguez F, Cohen C, Ober CK, Archer LA. Principles of Polymer Systems. 5th ed. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2003.

8. Santerre JP, Woodhouse K, Laroche G, Labow RS. Understanding the biodegradation of polyurethanes: From classical implants to tissue engineering materials. Biomaterials. 2006;26:7457–7470.

9. Saunders JH, Frisch KC. Polyurethanes: Chemistry and Technology, Part 1 Chemistry. New York, NY: Interscience Publishers; 1965.

10. Vert M. Polymeric biomaterials: Strategies of the past vs strategies of the future. Progress in Polymer Science. 2007;32:755–761.