D

Acrylics

Introduction

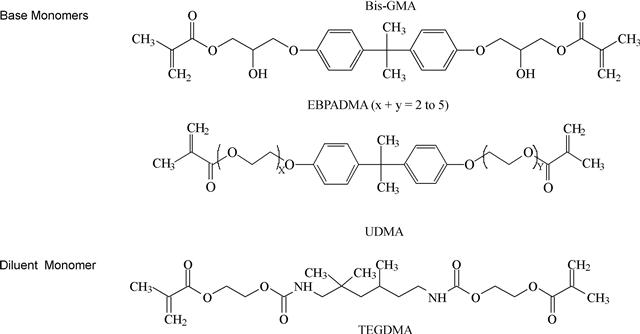

The modern development of tooth-colored dental polymeric composites owes much to R. L. Bowen of the American Dental Association for his pioneering studies at the National Bureau of Standards, now the National Institute of Standards and Technology. His recognition of the excellent matrix-forming potential of epoxy resins (oxiranes), as well as their poor ambient polymerization characteristics (slow under anionic catalysis and uncontrollable under the more rapid cationic catalysis then available) led him to the discovery of a unique hybrid monomer which combined the low polymerization contraction of epoxy resins with the excellent setting behavior of acrylic monomers (Bowen, 1956). His classical synthesis of the bulky, thermosetting dimethacrylate, Bis-GMA, 2,2-bis[p(2′-hydroxy-3′-methacryloxypropoxyphenyl)]propane (Figure D.1), his preparation of silica fillers that combined translucency and radiopacity while matching the refractive indices of the resin matrix, and his utilization of the technology of silane coupling agents, ushered in the modern era of esthetic dental composites (Bowen, 1963).

FIGURE D.1 Structures of commonly used base and diluent monomers.

Mono- and Multi-Methacrylate Monomers

Acrylics based on the monofunctional monomer methyl methacrylate (MMA) combined with poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) and a low viscosity dimethacrylate for cross-linking are mainly used in orthodontic appliances, e.g., bionator, bite plates, palatal expanders, retainers, and for removable prosthetic devices, such as partial and full dentures, temporary crowns, and bridges. Basic MMA/PMMA mixtures activated with chemical initiators have been widely used as bone cements for orthopedic applications (Shalaby et al., 2007). Further development has led to the incorporation of PMMA fibers, resulting in composites with moderately increased moduli and improved toughness (Gilbert et al., 1995). MMA and other monomethacrylates of moderate size and viscosity are only occasionally incorporated into dental restorative materials due to their relatively high molar double-bond concentration, and thus, increased polymerization shrinkage. However, functional monomethacrylates are widely used in adhesive formulations, and as coupling agents in composites, and are discussed below.

Base and Diluent Monomers

In preventive and restorative dentistry a variety of di- or multimethacrylates are photo and/or chemically cured into polymers that function as pit and fissure sealants, adhesives, veneer materials, and when combined with fillers, as esthetic or loadbearing composite restoratives. Typically, dental resins are composed of mixtures of two or more monomers that combine a relatively high viscosity dimethacrylate (base) monomer with a low viscosity dimethacrylate comonomer such as triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) to obtain resins with workable rheologies. The base resins 2,2-bis[p-(2′-hydroxy-3′-methacryloxypropoxy) phenylene]propane (Bis-GMA), ethoxylated bisphenol A dimethacrylate (EBPADMA) or 1,6-bis(methacryloxy-2-ethoxycarbonylamino)-2,4,4-trimethylhexane (UDMA) (Figure D.1) are among those most commonly employed in commercial dental resin-based materials.

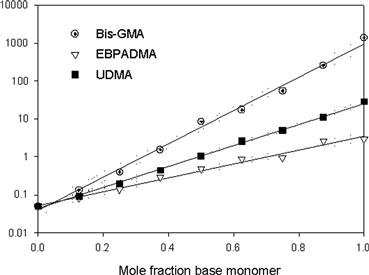

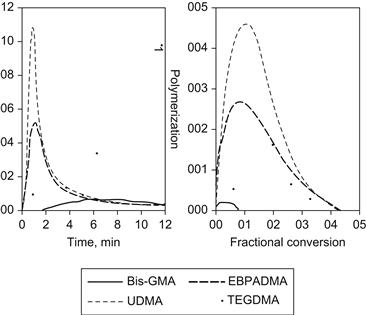

When cured at ambient temperature, free radicals convert the resin to a cross-linked three-dimensional polymer network. The free radicals are generated chemically from benzoyl peroxide and a tertiary aryl amine or through visible light irradiation using a photoinitiator, such as acyl-and bis-acylphosphine oxides, that yield radicals by photo cleavage or redox photoinitiator systems comprising camphorquinone or phenylpropanedione combined with aromatic or aliphatic tertiary amines that yield radicals by electron/hydrogen transfer mechanisms. For dental applications, rapid and efficient polymerization, in particular photopolymerization enabling on-command cure of dental resins, is a critical aspect of the clinical use of adhesives, sealants, and composites. Moreover, optimized cure is one of the most crucial parameters that govern the long-term performance of the polymeric material, affecting the biocompatibility by limiting the leaching of potentially cytotoxic materials from the cured polymers (Yoshii, 1997; Geurtsen et al., 1998). The extent of cure also affects the mechanical properties, e.g., fracture toughness, elastic moduli, flexural strength, and hardness (Cook, 1991; Ferracane et al., 1998). The base monomers are used in dental resin mixtures to enhance the physical and mechanical properties of the resulting polymers. Moreover, they minimize polymerization shrinkage and related stresses due to their relatively low methacrylate double-bond molar concentrations (Patel et al., 1987; Bogdal et al., 1997). While the addition of diluent monomers compromises the shrinkage, they are needed to reduce the viscosity of the base monomers to enable maximum filler loading, and to improve conversion and the physical and mechanical properties of the composite resins. When dental base monomers are combined with various proportions of the diluent monomer TEGDMA, the difference in their H-bonding potential results in compositions covering a broad range of viscosities (Figure D.2), and significantly different photopolymerization kinetics (Dickens et al., 2003). The structures of the individual monomers, and consequently the resin viscosities of the comonomer mixtures, strongly influence both the rate and extent of conversion of the photopolymerization process (Figure D.3). When compared at similar diluent concentrations, UDMA resins are significantly more reactive than Bis-GMA and EBPADMA resins. At higher diluent concentrations, EBPADMA resins provide the lowest photopolymerization reactivities. Optimum reactivities in the UDMA and EBPADMA resin systems are obtained with the addition of relatively small amounts of TEGDMA, whereas the Bis-GMA/TEGDMA resin system requires near equivalent mole ratios for highest reactivity (Dickens et al., 2003).

FIGURE D.2 Log viscosity of mixtures of Bis-GMA, EBPADMA, and UDMA with TEGDMA with linear regression and 95% confidence intervals (R2 = 0.987, 0.995, and 0.998, respectively).

FIGURE D.3 Thermograms (a), and rate/conversion profiles (b), of the DSC homo-polymerizations of the three base resins and the diluent monomer TEGDMA (light intensity: 100 μW/cm2). The early onset of the autoacceleration is particularly noticeable for UDMA and EBPADMA, while Bis-GMA and TEGDMA demonstrate a sluggish polymerization onset with very low conversion for Bis-GMA, and low polymerization rates.

Modified Base Monomers

Analogs and modifications of Bis-GMA and UDMA have been reported resulting in somewhat improved properties (Khatri et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2006). Derivatives of Bis-GMA having pendant n-alkyl urethane substituents exhibited lower viscosities and were more hydrophobic than Bis-GMA. Generally, the viscosity of these experimental monomers decreased with increasing chain length of the alkyl urethane substituent. Photopolymerization of the new monomers gave higher degrees of vinyl conversion compared to Bis-GMA, yet yielded lower polymerization shrinkage than Bis-GMA when compared at equivalent degrees of vinyl conversion (Antonucci and Stansbury, 1997; Peutzfeldt, 1997; Moszner and Salz, 2001, 2007). Modified urethane dimethacrylates have also been developed as alternatives for Bis-GMA; however, the improvements in physical properties were moderate, showing small changes in flexural strength and reduction in water uptake (Moszner et al., 2008).

Alternative Monomers with Improved Reactivity

In the late 1980s and early 1990s oxy bis-methacrylates were developed and evaluated as potential monomers for dental applications. It was found that these monomers undergo cyclopolymerization, resulting in polymers with high conversion yet low shrinkage (Stansbury, 1990). Other work by Stansbury introduced cyclic carbonates as highly reactive diluent monomers for dental applications (Berchtold et al., 2008).

Functionalized Monomers with Adhesive Properties

Adhesive Monomers

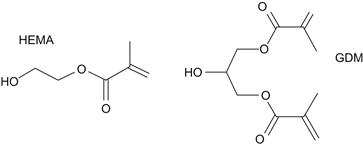

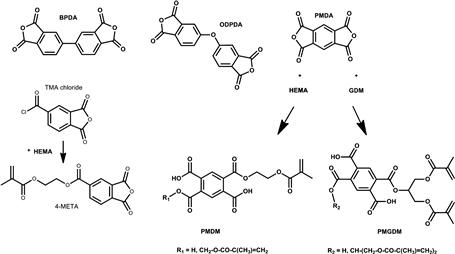

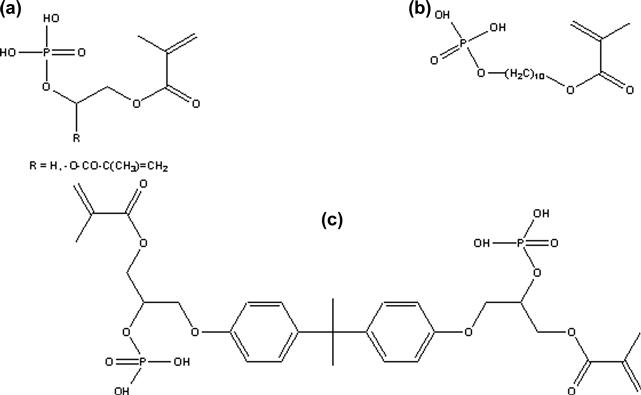

Currently, there are three main classes of free radical polymerizable restoratives available: (1) resin composites, which are mainly based on the methacrylate resins described above; (2) resin-modified glass ionomer cements, which are hybrids of polyacrylic acids having pendant methacrylate groups for free radical polymerization, while the carboxylic acid groups provide the means for an acid/base setting reaction with specialty ion-leachable aluminum fluorosilicate glasses; and (3) polyacid-modified composite resins based on carboxylic acid-containing methacrylates, also known as compomers. In contrast to resin composites, groups 2 and 3 contain, in addition to methacrylate or acrylate groups, carboxylic acid groups that are attached either to a backbone (group 2) or to the center core of the monomer (group 3). The acid groups are also capable of forming ionic bonds to apatitic calcium phosphate mineral and also strong hydrogen bonds to collagen, and thus promote adhesion to both enamel and dentin. Thus, acidic monomers together with other hydrophilic monomers (Figures D.4–D.6) are significant components of adhesive primers and bonding resins. In order to form durable bonds between a resin-based restorative and tooth structure it is essential to use an adhesive system that wets enamel and dentin well. Bonding to enamel is primarily achieved by micromechanical adhesion. Formation of resin tags in patent dentin tubules, but most importantly, mechanical interlocking of dentinal substrate and adhesive resins as a result of penetration of the adhesive into the intertubular dentin is believed to be responsible for durable dentin adhesion (Nakabayashi et al., 1982). The most widely used monomers in adhesives and bonding resins are the highly hydrophilic 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) and monomers that contain one or more carboxylic acid group, carboxylic acid anhydride or phosphoric acid groups (Figures D.4–D.6). The hydrophilic monomer HEMA and the acidic monomers have solubility parameters with high polar and hydrogen bonding components, resulting in high total cohesive energy density values. It has been demonstrated that bonding will be enhanced if fractional polarity and solubility parameters match those of the conditioned bonding substrate (Asmussen and Uno, 1993). Monomers with carboxylic acid groups (Figure D.5) are usually synthesized by reacting HEMA, glyceroldimethacrylate or other hydroxylated (meth)acrylate monomers with mono- or dicarboxylic acid anhydrides (Takeyama et al., 1978; Bowen et al., 1982; Venz and Dickens, 1993; Hammesfahr, 1997; Lopez-Suevos and Dickens, 2008). An adhesive monomer (4-META) with anhydride functionality is prepared from HEMA and trimellitic acid chloride (Figure D.5). To achieve improved interaction of adhesive monomers and tooth substrate beta cyclodextrines with multi-methacrylate/carboxylic-acid groups have been examined (Bowen et al., 2000; Hussain et al., 2004, 2005; Bowen et al., 2009). To improve the hydrolytic stability of monomer/polymer systems acrylamide/phosphonates have been proposed (Catel et al., 2008; Yeniad et al., 2008).

FIGURE D.4 Hydrophilic monomers: 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA); glycerol dimethacrylate (GDM).

FIGURE D.5 Structures of selected carboxylic acid dianhydrides and monomers: BPDA = biphenyl dianhydride; PMDA = pyromellitic dianhydride; ODPDA = oxydiphthalic dianhydride; TMA = trimellitic anhydride. The adhesive monomers 4-META, PMDM, and PMGDM are also shown. They are formed by the reaction between TMA chloride and HEMA, PMDA, and HEMA or PMDA and GDM, respectively.

FIGURE D.6 Exemplary structures of phosphate monomers: (a) HEMA-phosphate (R=H), glycerol dimethacrylate phosphate (R= –O–CO–C(CH3) = CH2); (b) MDP (methacryloyldecyldihydrogen phosphate); (c) Bis-GMA-phosphate.

Silane Coupling Agents

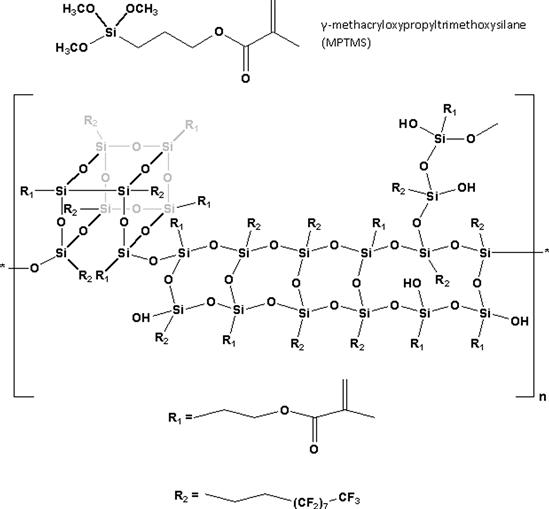

Except for pure gold fillings, all dental restoratives are multiphase materials having a composite microstructure involving one or more interfaces or interphases. Polymeric dental composites are interconnected heterogeneous materials that generally have three discernable phases: (1) a polymeric matrix or continuous phase formed by polymerization of a resin system consisting of one or more monomers/oligomers activated for chemical/photochemical polymerization; (2) a higher modulus dispersed phase consisting of fillers of various types (silica, ceramic, organic, etc.), sizes, shapes, and morphologies; and (3) an interface or interphase (usually derived from silane coupling agents) that mediates bonds between the continuous soft and the hard dispersed phases, thereby enhancing the moduli and mechanical properties of the relatively low modulus polymer phase, and also facilitating stress transfer between these phases by forming a unitary material. Adhesion of lower moduli polymeric matrices to higher moduli inorganic fillers can occur as a result of van der Waals forces, ionic interactions, hydrogen bonding, ionic or covalent bonding, interpenetrating polymer network formation and, for certain types of fillers, by a micromechanical interlocking mechanism. For most mineral reinforced dental composites, the primary interphasial linkage between the polymer matrix and the filler phase is by chemical bond formation, mediated through a dual functional organosilane (Antonucci et al., 2005). The most commonly used silane coupling agent, γ-methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane (MPTMS), is shown in Figure D.7.

FIGURE D.7 Structure of γ-methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane.

Monomers for Low Shrinking Polymers

Methacrylate Monomers: General Considerations

All methacrylate monomers undergo shrinkage when they polymerize. The volume a monomer occupies is governed by the monomer’s molecular structure, and by the inherent van der Waals forces that keep monomer molecules at distinct intermolecular distances. During polymerization the double bonds of neighboring (meth)acrylate groups are converted to covalently bonded single bonds, thereby linking individual mers and forming macromers. If di- or multimethacrylates are present, a three-dimensional polymer network is formed. After the initiation of polymerization, the free radical chain growth of multimethacrylates initiated by commonly used chemical or photoinitiators is hindered by the rapid formation of the three-dimensional network, increasing the viscosity of the gel and decreasing the mobility of the monomer or short chain polymer molecules, which then limits the vinyl conversion. Thus, residual monomer and pendant double bonds are commonly present in these types of polymers to various degrees (Ruyter, 1985; Dickens et al., 2003). Monomer and short chain oligomers (a limited number of linked monomer units) not incorporated into the polymer network can potentially leach out, and both unsaturated residual and pendant methacrylate groups act as internal plasticizers that may influence the biocompatibility, physical properties, and longevity of the material (Asmussen, 1982; Ruyter, 1985). As polymerization shrinkage and remaining double bonds are directly correlated, these properties ought to be considered together when characterizing “low shrinking” materials. The polymerization process results in a reduction in free volume, measurable as linear or volumetric polymerization shrinkage. Polymerization contraction stresses occur as a consequence of polymerization shrinkage. For highly cross-linked systems, the majority of shrinkage stress develops during and after the vitrification stage (Lu et al., 2005), and is a significant concern in numerous dental applications. The most detrimental effect caused by shrinkage stress is debonding at the composite/tooth interface, which results in gap formation and microleakage that provides a route for bacterial infiltration that can contribute to secondary caries. Strategies to reduce the polymerization shrinkage in resin-based materials comprise varying the monomer structure and resin composition, increasing the number of atoms between methacrylate groups, and modifying type, size, size distribution, and amount of fillers added to the resin matrix. Most highly filled resin composites shrink between 2% and 3%.

Molecular Structure and Size Effects

In the last decade, modifications in the monomer structure for reducing the shrinkage and related stresses included hyperbranched monomers (Holter et al., 1997), liquid crystalline methacrylates (Hammesfahr, 1997; Satsangi et al., 2005), and dendritic monomers (Viljanen et al., 2005). However, these types of resins have given mixed results with respect to the physical and mechanical properties of their composites. Other recent strategies to lowering the polymerization shrinkage and stresses included use of high molecular weight bis(vinylcyclopropane)-based monomers containing a cholesteryl group (Choi et al., 2005), and dimer acid-based monomers (Trujillo-Lemon et al., 2006). It was found that these monomers contributed to significantly reduced shrinkage. The dimer acid-based monomers have found application in a commercial composite.

Thiol-ene Systems

Recently, novel photopolymerizable monomer systems have been developed which are based on thiol-ene resin chemistry involving free radical step growth rather than chain growth polymerization (Cramer and Bowman, 2001). These systems, especially oligomeric thiol-ene materials, produce polymers having high conversion and dramatically reduced polymerization shrinkage stress (Carioscia et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2005; Carioscia et al., 2007). While these systems undergo more rapid reaction with higher functional group conversion, they are mechanically inferior to current Bis-GMA/TEGDMA resins. Other work reported the application of thiol-allyl ether-methacrylate ternary systems (Kilambi et al., 2007) with an interesting approach using a two-stage polymerization process. During the first stage, highly functional oligomeric methacrylates are formed. Because this process occurs in the pre-gel stage, it does not contribute to shrinkage stress. The allyl ether conversion and shrinkage stress develop subsequently, and thus these systems have high cross-link density and improved mechanical properties, yet significantly reduced shrinkage stress when compared to previously developed thiol-ene systems.

Ring Opening Monomers: Spiroorthocarbonates

To reduce polymerization shrinkage while maintaining high conversion and acceptable material properties, non-methacrylated ring opening spiroorthocarbonate (SOC) monomers were evaluated (Thompson et al., 1979; Bailey, 1990; Byerley et al., 1992; Eick et al., 1993). Modified vinyl SOCs in combination with methacrylate monomers achieved tensile strengths that were comparable to their SOC-free controls (Stansbury, 1992). Re-examining the concept of potentially expanding resins, Stansbury et al. investigated a number of tetraoxaspirononanes either with cationic initiation alone or a combined cationic/free radical initiation (Ge et al., 2005), while others used tetraoxaspiroundecanes in combination with siloranes (Chappelow et al., 2007). Both studies confirmed the ring-opening mechanism. However, it was pointed out that even a trace amount of moisture had a significant adverse impact on both the reaction kinetics and the polymerization course of the hydrolytically vulnerable tetraoxaspirononanes (Ge et al., 2005).

Monomers Containing Silicon and/or Epoxy Functionality

Various approaches have been taken to include silicon-based monomers in addition to the silane coupling agents into dental composites. The chemistry of functional organosilanes (or silane coupling agents as they are commonly known) can be quite complex, involving hydrolytically initiated self-condensation reactions in solvents (including monomers) that can culminate in oligomeric silsesquioxane structures, exchange reactions with hydroxylated or carboxylated monomers to form silyl ethers and esters, as well as the formation of silane-derived interfaces by adhesive coupling with siliceous mineral surfaces (Antonucci et al., 2005). Examples of silsesquioxane oligomeric structures (together with MPTMS) are shown in Figure D.7. It was recently shown that the fluorinated silsesquioxane oligomers, when added to EBPADMA, led to similarly acceptable mechanical properties as the silsesquioxane-free control, while exhibiting significantly reduced polymerization shrinkage stresses (Dickens et al., 2009). It is hypothesized that the bulky nature of the oligomeric additive, possibly in combination with fluoridated pendant chains being repelled from the more hydrophilic bulk, increased the free volume of the oligomers, and thus contributed to the low shrinkage stresses in these composites. Adding 2% of the novel organic/inorganic hybrid monomer POSS-MA (polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane methacrylate) into Bis/TEGDMA resins showed moderate improvement of the mechanical properties. However, due to the high number of polymerizable methacrylate groups, the polymerization shrinkage was not improved (Fong et al., 2005). Cycloaliphatic epoxy (oxiranes) monomers formulated with polyol network extenders and cured with cationic onium/camphorquinone initiators have been considered as potential candidates to reduce polymerization shrinkage (Tilbrook et al., 2000). They exhibit lower polymerization shrinkage, no oxygen inhibition layer, higher strength, equivalent hardness, and acceptable glass transition temperatures as many methacrylate-based resins. However, the water uptake of these epoxy-polyol materials when immersed in water was nearly twice that of the Bis-GMA/TEGDMA control.

Even lower shrinkage and shrinkage stress values have been reported for a new class of methacrylate-free photocationically polymerizing low-shrinkage composite resins (Weinmann et al., 2005; Ilie et al., 2007). The monomers are named siloranes, indicating that their chemical structure comprises a combination of siloxanes and oxiranes. The reduction in polymerization shrinkage and resulting shrinkage stresses is based on two principles: epoxy-ring opening during setting of a large cyclic siloxane monomer core structure; and relatively slow polymerization kinetics resulting in somewhat delayed gelation and the possibility of stress relaxation. Physical properties of silorane-based materials match those of conventional composite resins. The silorane-based composites require special bonding and coupling agents based on the same chemistry to allow copolymerization between bonding agent and resin matrix, and also between the silanized reinforcing glass filler and the resin matrix.

Anticariogenic Strategies

To combat biofilm attachment to restoration surfaces and recurrent caries, a family of fluoride-releasing resins has been developed for adhesive applications, temporary crowns, and removable acrylic devices. These resins contain fluoride ions, which are covalently bound to positively charged sites within the polymer network and can be released via an exchange mechanism involving anions from oral fluids (Rawls, 1987). More recent approaches include tetrabutylammonium tetrafluoroborate incorporated into a hydrophilic monomer system (Glasspoole et al., 2001); complexing zirconium fluoride with a chelating monomer (Ling et al., 2009); or incorporating antibacterial functionality into monomers as demonstrated for methacryloyloxydodecyl-pyridinium bromide monomer (Imazato et al., 1994; Imazato, 2009).

Summary

Dental resin chemistry has made significant progress in the last decade in improving clinical performance and addressing some of the most pertinent problems in restorative dentistry, i.e., polymerization shrinkage and shrinkage stress that potentially affect recurrent caries through bacterial ingress into marginal crevices around dental restorations. Thus, the most significant improvements for better dental health are the successful reduction of polymerization shrinkage and polymerization shrinkage stresses for improved marginal integrity; the development of resin chemistries that enhance the hydrolytic stability of the restoratives; and the development of monomers with antibacterial properties designed to increase the resistance of tooth structure to bacterial attack.

Disclaimer

Certain commercial materials and equipment are identified in this paper for adequate definition of the experimental procedure. In no instance does such identification imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology or the ADA Foundation or that the material or equipment identified is necessarily the best available for the purpose.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the American Dental Association Foundation, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Grant No. DE13298, and the NIDCR/NIST Interagency Agreement YI-DE 7005-01.

Bibliography

1. Antonucci JM, Stansbury JW. Molecular Designed Dental Polymers. In: Arshady R, ed. Desk Reference of Functional Polymers: Synthesis and Applications. Washington, D.C: American Chemical Society; 1997:719–738.

2. Antonucci JM, Dickens SH, Fowler BO, Xu HH K, McDonough WG. Chemistry of silanes: Interfaces in dental polymers and composites. J Res Natl Inst Stand Technol. 2005;110(5):541–558.

3. Asmussen E. Restorative resins: Hardness and strength vs quantity of remaining double bonds. Scand J Dent Res. 1982;90(6):484–489.

4. Asmussen E, Uno S. Solubility parameters, fractional polarities, and bond strengths of some intermediary resins used in dentin bonding. J Dent Res. 1993;72(3):558–565.

5. Bailey WJ. Matrices that expand on curing for high-strength composites and adhesives. Mater Sci Eng A. 1990;126:271–279.

6. Berchtold KA, Nie J, Stansbury JW, Bowman CN. Reactivity of monovinyl (meth)acrylates containing cyclic carbonates. Macromolecules. 2008;41(23):9035–9043.

7. Bogdal D, Pielichowski J, Boron A. Application of diol dimethacrylates in dental composites and their influence on polymerization shrinkage. J Appl Polym Sci. 1997;66(12):2333–2337.

8. Bowen RL. Use of epoxy resins in restorative materials. J Dent Res. 1956;35(3):360–369.

9. Bowen RL. Properties of a silica-reinforced polymer for dental restorations. J Am Dent Assoc. 1963;66(1):57–64.

10. Bowen RL, Cobb EN, Rapson JE. Adhesive bonding of various materials to hard tooth tissues: Improvement in bond strength to dentin. J Dent Res. 1982;61(9):1070–1076.

11. Bowen RL, Farahani M, Dickens SH, Guttman CM. MALDI-TOF MS analysis of a library of polymerizable cyclodextrin derivatives. J Dent Res. 2000;79(4):905–911.

12. Bowen RL, Carey CM, Flynn KM, Guttman CM. Synthesis of polymerizable cyclodextrin derivatives for use in adhesion-promoting monomer formulations. J Res Natl Inst Stand Technol. 2009;114(1):1–9.

13. Byerley TJ, Eick JD, Chen GP, Chappelow CC, Millich F. Synthesis and polymerization of new expanding dental monomers. Dent Mater. 1992;8(5–6):345–350.

14. Carioscia JA, Lu H, Stansbury JW, Bowman CN. Thiol-ene oligomers as dental restorative materials. Dent Mater. 2005;21(12):1137–1143.

15. Carioscia JA, Stansbury JW, Bowman CN. Evaluation and control of thiol-ene/thiol-epoxy hybrid networks. Polymer. 2007;48(6):1526–1532.

16. Catel Y, Degrange M, Le Pluart L, Madec PJ, Pham TN, et al. Synthesis, photopolymerization and adhesive properties of new hydrolytically stable phosphonic acids for dental applications. J Polym Sci [A1]. 2008;46(21):7074–7090.

17. Chappelow CC, Pinzino CS, Chen SS, Jeang L, Eick JD. Photopolymerization of a novel tetraoxaspiroundecane and silicon-containing oxiranes. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;103(1):336–344.

18. Choi S, Hessamian A, Tabatabai M, Fischer UK, Moszner N, et al. Bis(vinylcyclopropane) and bis(methacrylate) monomers with cholesteryl group for dental composites. E-Polymers 2005.

19. Cook WD. Fracture and structure of highly cross-linked polymer composites. J Appl Polym Sci. 1991;42(5):1259–1269.

20. Cramer NB, Bowman CN. Kinetics of thiol-ene and thiol-acrylate photopolymerizations with real-time Fourier transform infrared. J Polym Sci Part A – Polym Chem. 2001;39(19):3311–3319.

21. Dickens SH, Stansbury JW, Choi KM, Floyd CJ E. Photopolymerization kinetics of methacrylate dental resins. Macromolecules. 2003;36(16):6043–6053.

22. Dickens SH, Luther D, Antonucci JM. Effects of silane oligomers on composite properties. J Dent Res. 2009;87(Spec. Iss. A):1648.

23. Eick JD, Byerley TJ, Chappell RP, Chen GR, Bowles CQ, et al. Properties of expanding soc/epoxy copolymers for dental use in dental composites. Dent Mater. 1993;9(2):123–127.

24. Ferracane JL, Berge HX, Condon JR. In vitro aging of dental composites in water: Effect of degree of conversion, filler volume, and filler/matrix coupling. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;42(3):465–472.

25. Fong H, Dickens SH, Flaim GM. Evaluation of dental restorative composites containing polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane methacrylate. Dent Mater. 2005;21(6):520–529.

26. Ge JH, Trujillo M, Stansbury J. Synthesis and photopolymerization of low shrinkage methacrylate monomers containing bulky substituent groups. Dent Mater. 2005;21(12):1163–1169.

27. Geurtsen W, Lehmann F, Spahl W, Leyhausen G. Cytotoxicity of 35 dental resin composite monomers/additives in permanent 3T3 and three human primary fibroblast cultures. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;41(3):474–480.

28. Gilbert JL, Ney DS, Lautenschlager EP. Self-reinforced composite poly(methyl methacrylate), static and fatigue properties. Biomaterials. 1995;16(14):1043–1055.

29. Glasspoole EA, Erickson RL, Davidson CL. A fluoride-releasing composite for dental applications. Dent Mater. 2001;17(2):127–133.

30. Hammesfahr PD. Compomers and hydromers for use in restorative dental procedures. Am Chem Soc Div Polym Chem Polym Prepr. 1997;38(2):131–132.

31. Holter D, Frey H, Mulhaupt R, Klee JE. Branched bismethacrylates based on Bis-GMA: A systematic route to low shrinkage composites. Am Chem Soc. 1997;214 9–Poly.

32. Hussain LA, Dickens SH, Bowen RL. Effects of polymerization initiator complexation in methacrylated beta-cyclodextrin formulations. Dent Mater. 2004;20(6):513–521.

33. Hussain LA, Dickens SH, Bowen RL. Properties of eight methacrylated beta-cyclodextrin composite formulations. Dent Mater. 2005;21(3):210–216.

34. Ilie N, Jelen E, Clementino-Luedemann T, Hickel R. Low-shrinkage composite for dental application. Dent Mater J. 2007;26(2):149–155.

35. Imazato S. Bio-active restorative materials with antibacterial effects: New dimension of innovation in restorative dentistry. Dent Mater J. 2009;28(1):11–19.

36. Imazato S, Torii M, Tsuchitani Y, McCabe JF, Russell RRB. Incorporation of bacterial inhibitor into resin composite. J Dent Res. 1994;73(8):1437–1443.

37. Khatri CA, Stansbury JW, Schultheisz CR, Antonucci JM. Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of urethane derivatives of Bis-GMA. Dent Mater. 2003;19(7):584–588.

38. Kilambi H, Reddy SK, Schneidewind L, Lee TY, Stansbury JW, et al. Design, development, and evaluation of monovinyl acrylates characterized by secondary functionalities as reactive diluents to diacrylates. Macromolecules. 2007;40(17):6112–6118.

39. Kim JW, Kim LU, Kim CK, Cho BH, Kim OY. Characteristics of novel dental composites containing 2,2-bis[4-(2-methoxy-3-methacryloyloxy propoxy) phenyl] propane as a base resin. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(1):154–160.

40. Ling L, Xu X, Choi GY, Billodeaux D, Guo G, et al. Novel F-releasing composite with improved mechanical properties. J Dent Res. 2009;88(1):83–88.

41. Lopez-Suevos F, Dickens SH. Degree of cure and fracture properties of experimental acid-resin modified composites under wet and dry conditions. Dent Mater. 2008;24(6):778–785.

42. Lu H, Stansbury JW, Bowman CN. Impact of curing protocol on conversion and shrinkage stress. J Dent Res. 2005;84(9):822–826.

43. Moszner N, Salz U. New developments of polymer dental composites. Prog Polym Sci. 2001;26(4):535–576.

44. Moszner N, Salz U. Recent developments of new components for dental adhesives and composites. Macromol Mater Eng. 2007;292(3):245–271.

45. Moszner N, Fischer UK, Angermann J, Rheinberger V. A partially aromatic urethane dimethacrylate as a new substitute for Bis-GMA in restorative composites. Dent Mater. 2008;24(5):694–699.

46. Nakabayashi N, Kojima K, Masuhara E. The promotion of adhesion by the infiltration of monomers into tooth substrates. J Biomed Mater Res. 1982;16(3):265–273.

47. Patel MP, Braden M, Davy KW. Polymerization shrinkage of methacrylate esters. Biomaterials. 1987;8(1):53–56.

48. Peutzfeldt A. Resin composites in dentistry: The monomer systems. Eur J Oral Sci. 1997;105(2):97–116.

49. Rawls HR. Fluoride-releasing acrylics. J Biomater Appl. 1987;1(3):382–405.

50. Ruyter IE. Monomer Systems and Polymerization. In: Vanherle G, Smith DC, eds. Posterior Composite Resin Dental Restorative Materials. The Netherlands: Peter Szulc Publishing Co; 1985;109–135.

51. Satsangi N, Rawls HR, Norling BK. Synthesis of low-shrinkage polymerizable methacrylate liquid-crystal monomers. J Biomed Mater Res Part B: Appl Biomater. 2005;74B(2):706–711.

52. Shalaby SW, Nagatomi SD, Peniston SJ. Polymeric Biomaterials for Articulating Joint Repair and Total Joint Replacement. In: Shalaby SW, Salz U, eds. Polymers for Dental and Orthopedic Applications. Boca Raton, London, New York: CRC Press; 2007.

53. Stansbury JW. Cyclopolymerizable monomers for use in dental resin composites. J Dent Res. 1990;69(3):844–848.

54. Stansbury JW. Synthesis and evaluation of new oxaspiro monomers for double-ring opening polymerization. J Dent Res. 1992;71(7):1408–1412.

55. Takeyama M, Kashibuchi N, Nakabayashi N, Masuhara E. Studies on dental self-curing resins (17) Adhesion of PMMA with bovine enamel or dental alloys. J Jpn Dent Appar Mater. 1978;19:179–185.

56. Thompson VP, Williams EF, Bailey WJ. Dental resins with reduced shrinkage during hardening. J Dent Res. 1979;58(5):1522–1532.

57. Tilbrook DA, Clarke RL, Howle NE, Braden M. Photocurable epoxy-polyol matrices for use in dental composites I. Biomaterials. 2000;21(17):1743–1753.

58. Trujillo-Lemon M, Ge JH, Lu H, Tanaka J, Stansbury JW. Dimethacrylate derivatives of dimer acid. J Polym Sci [A1]. 2006;44(12):3921–3929.

59. Venz S, Dickens B. Modified surface-active monomers for adhesive bonding to dentin. J Dent Res. 1993;72(3):582–586.

60. Viljanen EK, Lassila LV J, Skrifvars M, Vallittu PK. Degree of conversion and flexural properties of a dendrimer/methyl methacrylate copolymer: Design of experiments and statistical screening. Dent Mater. 2005;21(2):172–177.

61. Weinmann W, Thalacker C, Guggenberger R. Siloranes in dental composites. Dent Mater. 2005;21(1):68–74.

62. Yeniad B, Albayrak AZ, Olcum NC, Avci D. Synthesis and photopolymerizations of new phosphonated monomers for dental applications. J Polym Sci [A1]. 2008;46(6):2290–2299.

63. Yoshii E. Cytotoxic effects of acrylates and methacrylates: Relationships of monomer structures and cytotoxicity. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;37(4):517–524.