Chapter I.2.15

Textured and Porous Materials

Introduction

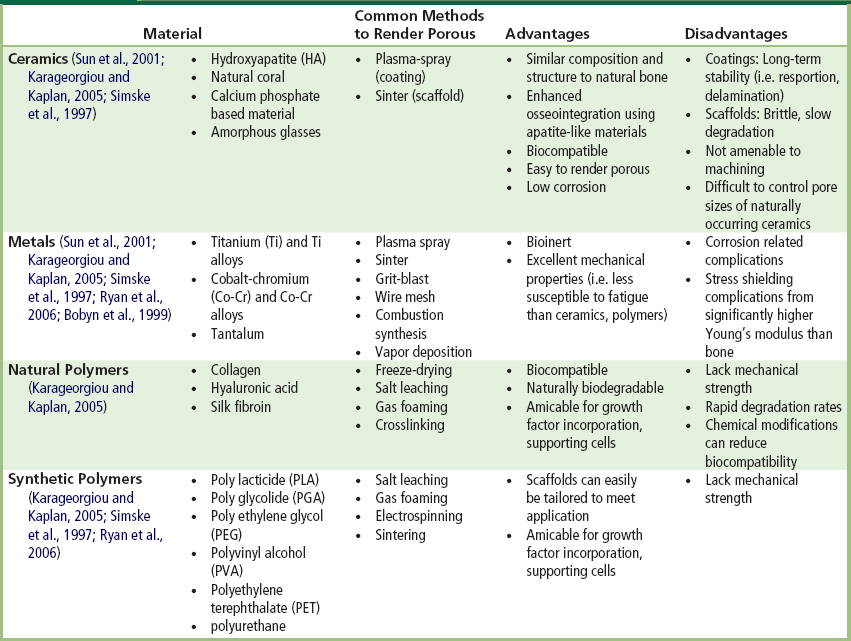

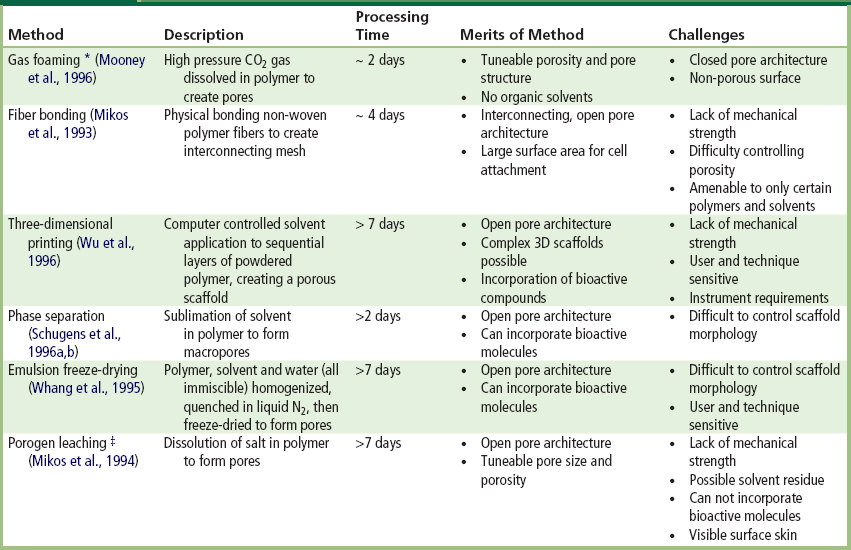

The use of porous and textured implants to stimulate tissue ingrowth, disrupt fibrosis and promote angiogenesis dates back as far as the 1940s, and is an early example of a tissue engineering-like approach to biomaterials. Device function and placement in the body dictates what material would be most suitable for a particular application. Numerous materials (metals, ceramics, natural and synthetic polymers) can be textured or rendered porous using a wide variety of techniques (Tables I.2.15.1 and I.2.15.2).

TABLE I.2.15.1 Common Materials used in Orthopedic and Dental Applications for Fabricating Porous Coatings or Porous Scaffolds

Note: Stainless steel is not commonly used in porous form since it is not as corrosive resistant as Ti, Co-Cr and their alloys (Simske et al., 1997).

TABLE I.2.15.2 Summary of Methods Developed for Fabricating Porous Three-Dimensional Biodegradable Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering (Chen et al., 2002; Hutmacher, 2000; Yang et al., 2001)

∗Gas foaming with CO2 has also been combined with salt leaching to create open pore architecture with a processing time of approximately 4 days (Harris et al., 1998).

‡Porogen leaching has also been combined with gas foaming using ammonium bicarbonate as salt leaching/gas foaming agent, reducing processing time to 24 hours with no surface skin layer (Nam et al., 2000).

The extent to which a textured or porous material can influence the host tissue response is related to pore size and porosity. While no one pore size fits all applications, the majority of porous materials employed possess an open architecture with interconnecting pores that are sufficiently large to support cell and tissue infiltration, but small enough to disrupt fibrous tissue deposition (Sharkawy et al., 1998). Textured implants with open architecture pore structures also appear to form thinner foreign-body capsules (Salzmann et al., 1997; Sharkawy et al., 1997; Updike et al., 2000; Ward et al., 2002) (also see Chapter II.3.2). Porous surfaces promote tissue ingrowth that minimizes interfacial cell necrosis from mechanical shear forces, that in turn results in less inflammation and reduced capsule thickness (Rosengren et al., 1999).

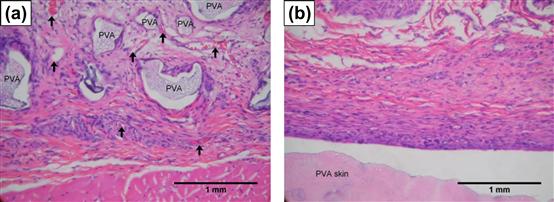

Tissue ingrowth strongly influences the long-term success of orthopedic, dental, ocular, percutaneous, and cardiovascular implants. In most instances, texturing is used to promote tissue ingrowth for improved tissue–implant stabilization. Other important effects incited by implant texturing include disruption of fibrous encapsulation, improved tissue healing, and increased vascularization of the tissue surrounding the implant (Figure I.2.15.1).

FIGURE I.2.15.1 Difference in cellular and tissue response around polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) implanted in rat subcutaneous tissue after 3 weeks: (a) porous PVA (300 μm pores) promoted fibrovascular ingrowth (arrows denote capillaries); and (b) smooth PVA developed dense avascular capsule adjacent to material surface.

(From Koschwanez, H. E. (2004). Unpublished data.)

These recurring concepts appear throughout this chapter in several medical devices, i.e., breast implants, bone regenerative implants and orthopedic implant coatings, ocular implants and glaucoma drainage devices, synthetic vascular grafts, and percutaneous devices, with a separate section for percutaneous glucose sensors. For each device, the benefits and challenges of using textured surfaces will be discussed, in addition to optimal pore size, choice of implant material, and theorized mechanisms of how these surface topologies influence host response.

Stimulating Tissue Ingrowth

Porosity to Promote Bone Regeneration and Implant Fixation

Porous materials are often used to repair severely fractured or malformed bone. These bone regeneration scaffolds must provide structural support to the newly forming bone, share mechanical properties similar to the host bone, be biocompatible, and biodegrade at a rate synergistic with bone remodeling (Karageorgiou and Kaplan, 2005). Controlling pore size and porosity is essential in creating a scaffold that meets the needs of both the specific repair site (mechanical, mineral, and cellular properties) and the patient (age, activity level, nutrition, disease) (Karageorgiou and Kaplan, 2005).

Of the over 2,000,000 total joint replacements performed annually worldwide (Kuster, 2002; de Pina et al., 2011), an increasing number of implants are employing textured fixation layers to minimize latent complications of prostheses loosening (Chang et al., 1996). These fixation layers mostly consist of metal beads sintered to the implant surface, thin coatings of hydroxyapatite or grooves or pitted surfaces (Simske et al., 1997; Sun et al., 2001). Candidates for textured implants are typically individuals with replacement joints (total knee, acetabular component) implanted in cancellous bone, as this tissue type consistently achieves a stable implant–host bone attachment (Bloebaum et al., 2007). Improved implant fixation through osteointegration into porous implants also reduces stress shielding (a condition that occurs from uneven load distribution between the host bone and implant; see Chapter II.5.6). As the stiffer implant material bears more load than the bone, the bone becomes weakened and susceptible to fracture and implant loosening.

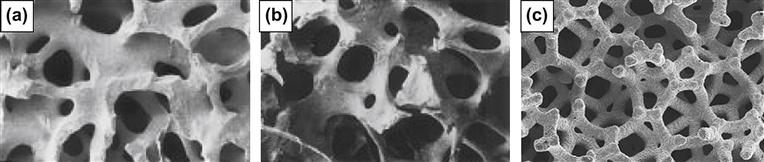

Rate of bone growth into a porous material is highly dependent on pore size (Klawitter et al., 1976) and pore connectivity (Hing et al., 2004). Bone is naturally porous, with pore sizes ranging from 1 to 100 μm (Simske et al., 1997) (Figure I.2.15.2). The optimum pore size for bone ingrowth into porous-coated prostheses, regardless of material, ranges from 100–400 μm (Simske et al., 1997; Kienapfel et al., 1999; Ryan et al., 2006); however, interconnecting pores as small as 50 μm have been shown to be effective primarily for encouraging blood vessel growth within the implant (Klawitter et al., 1976; Bobyn et al., 1980; Simske et al., 1997; Ryan et al., 2006). To support continuous tissue ingrowth, a minimum pore size of 100 μm is required. Although increased fixation strength occurs with increased pore size when using pores less than 100 μm (Kienapfel et al., 1999), no such relationship has been observed for pore size in the 150–400 μm range. Interestingly, while the size of the interconnecting pores is critical for osteointegration, pore shape does not appear to influence biological response (Turner et al., 1986; Ryan et al., 2006).

FIGURE I.2.15.2 Similar porous structure and composition between: (a) coralline hydroxyapatite; and (b) human cancellous bone. (c) Chemical vapor deposition of tantalum on a vitreous carbon skeleton creates a porous metal construct that also mimics native bone structure.

(a,b: Courtesy of Interpore).

Osteointegration will not occur if fibrous tissue ingrowth precedes first. Fibrous ingrowth has been shown to occur with pores smaller than 15 μm (Simske et al., 1997) or larger than 1000 μm (Ryan et al., 2006), suggesting different cell types have preferential pore sizes. Increased micromotion between the implant and host bone will also promote fibrous connective tissue ingrowth instead of bony ingrowth (Kienapfel et al., 1999; Ryan et al., 2006). This fibrotic tissue may inhibit bone formation or prevent bony ingrowth from the host tissue, ultimately reducing implant fixation strength (Ryan et al., 2006).

Several porous ceramics, metals, and polymers have been investigated for orthopedic implants, with porous metals being the most widely employed for loadbearing applications (Ryan et al., 2006) (Table I.2.15.1). However, porous materials may have substantially reduced dynamic fatigue strength. Additionally, the pores may create stress concentration sites for microfractures, compounding implant fatigue (Simske et al., 1997). Additionally, porous metals may exhibit higher corrosion rates, due to increased surface area, raising long-term safety concerns (Ryan et al., 2006). Composite implants blending two or more materials, such as plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium, could provide the best opportunity to match implant and bone properties (Simske et al., 1997; Sun et al., 2001). Another interesting possibility is creating scaffolds with gradient pore size and porosity to promote osteogenesis at one end of the scaffold and osteochondrial ossification at the other, ideal for bone-cartilage repair. Investigations are also underway to integrate biomolecules into scaffold materials to further promote bone repair (Karageorgiou and Kaplan, 2005).

Texturing to Improve Healing and Restore Motion in Eye Implants

When the eye is enucleated due to severe trauma, intraocular cancer or removal of a blind and painful eye, the lost tissue may be compensated with an orbital implant (Chalasani et al., 2007; Sami et al., 2007). Important considerations with orbital implants include fit, optimized prosthesis motility, and minimized long-term complications, such as implant exposure, extrusion, migration, and infection (Goldberg et al., 1994).

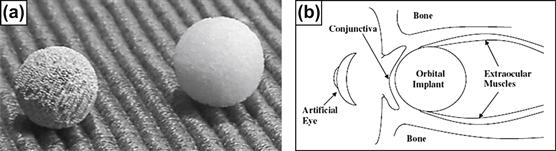

Numerous materials have been used in orbital implant design, including glasses, silicones, and acrylics (Chalasani et al., 2007). Porous materials such as hydroxyapatite (HA), porous polyethylene (PPE), and aluminum oxide (AO) are showing increased popularity (Chalasani et al., 2007; Sami et al., 2007) (Figure I.2.15.3). HA, the mineral component of bone, has good biocompatibility; however, suturing this material to the extraocular muscles is difficult. Abrasion from roughened HA implants may exacerbate inflammation and lead to latent implant exposure. The roughness of HA also makes surgical insertion more challenging (Chalasani et al., 2007). PPE is flexible, easily molded, relatively inexpensive, and can be sutured to surrounding tissue (Chalasani et al., 2007). PPE appears to incite less inflammation and fibrosis than HA (Goldberg et al., 1994). AO is robust, biocompatible, easy to manufacture, and less expensive than HA (Chalasani et al., 2007). AO is the newest porous material used in orbital implants, with only one commercially available implant (Chalasani et al., 2007). More long-term studies are required to ensure clinical efficacy of this material as an orbital implant (Sami et al., 2007).

FIGURE I.2.15.3 (a) Examples of porous hydroxyapatite (left) and polyethylene (right) orbital implants; (b) sagittal view of human orbit showing placement of orbital implant.

HA and PPE roughly resemble the structure of trabecular bone (Chalasani et al., 2007; Sami et al., 2007), and encourage fibrovascularization (tissue ingrowth) of the implant within weeks of implantation (Chalasani et al., 2007). Optimal pore size for orbital implants ranges from 150 μm to 400 μm, with preference closer to 400 μm for more complete fibrovascularization (Goldberg et al., 1994; Rubin et al., 1994). Highly porous materials with interconnecting pores of uniform diameter are more favourable for facilitating cell movement and nutrient flow within the implant, encouraging tissue ingrowth (Chalasani et al., 2007).

Porous orbital materials are stiffer in relation to the conjunctiva and surrounding tissue (Chalasani et al., 2007). This compliance mismatch coupled with constant implant movement by extraocular muscles may exacerbate inflammation, leading to tissue necrosis and eventual implant exposure (Chalasani et al., 2007). Porous hydrogels may be a promising alternative to the current implant materials, as these water-based materials possess physical properties similar to native tissue (Chalasani et al., 2007).

Disrupting Fibrosis

Texturing to Disrupt Capsular Contracture of Breast Prostheses

One of the most common cosmetic surgical procedures in the United States is breast augmentation (Gampper et al., 2007). All breast implants are constructed with a smoothed or textured shell of silicone elastomer, a material pervasively used in medical devices. The majority of implants are filled with saline rather than silicone gel, after the 1992 FDA voluntary moratorium on silicone gel implants (Gampper et al., 2007); however, gel-filled implants are making a comeback owing to more lifelike mechanical properties.

Fibrous capsular contraction is the most common complication in breast augmentation surgery, with long-term contracture incidence reported at 15–25% (Malata et al., 1997; Benediktsson and Perbeck, 2006). As with any foreign object implanted in the body, the host response to a breast implant is to construct a fibrous capsule around the foreign-body, “walling off” the implant from the rest of the body. During the first several months post-implantation the fibrous capsule begins to contract, resulting in breast firmness that may lead to patient discomfort and disfigurement.

Several possible factors contribute to breast implant capsular contracture, including implant surface (smooth versus porous), implant placement (submuscular versus subglandular), implant shape (i.e., fill volume), bacterial infection, bleeding, surgical technique, post-operative care (i.e., breast massage), and patient health (Burkhardt et al., 1986; Gabriel et al., 1997; Becker and Springer, 1999; Embrey et al., 1999). Contracture has been found to be an independent breast-based, not patient-based, phenomenon (i.e., one breast may experience contracture while the other breast may not) (Burkhardt, 1984; Burkhardt et al., 1986).

Surface texturing has been investigated as a means to reduce capsular contracture for decades. Texturing has been reported to reduce early capsular contracture in subglandular breast augmentation (Wong et al., 2006); however, it is not conclusive whether texturing reduces contracture incidence (Bucky et al., 1994; Tarpila et al., 1997; Fagrell et al., 2001) or simply delays contracture onset (Wong et al., 2006).

The type of texturing, pore size or implant material does not appear to be as important as simply disrupting surface smoothness (McCurdy, 1990; Caffee, 1994; Danino et al., 2001). One clinical study comparing saline-filled silicone implants textured with either 75–150 μm or 600–800 μm pore size concluded that both morphologies were effective in reducing capsular contracture (Danino et al., 2001). The mechanisms contributing to reduced capsular contracture with textured implants still remain poorly understood (Pollock, 1993; Caffee, 1994; Wong et al., 2006). Disrupting the smooth surface with texturing influences collagen arrangement and structure, macrophage population, micromotion, and risk of infection (Taylor and Gibbons, 1983; McCurdy, 1990). The collagen arrangement hypothesis is that irregularly arranged collagen fibers at textured surfaces are less able to generate cooperative contractile forces typical of maturing scar tissue (McCurdy, 1990; Pennisi, 1990), while another hypothesis is that irregularly aligned collagen fibers are more susceptible to collagenase degradation (Raykhlin and Kogan, 1961; Taylor and Gibbons, 1983). Textured implants have been shown to have more macrophages and less collagen surrounding them compared to smooth implants, indicating that macrophages may be degrading the capsule as it forms, minimizing capsule thickness (Taylor and Gibbons, 1983; McCurdy, 1990). More functional hypthotheses are that the tissue integration promoted by the textured surface may be either reducing micromotion, thus reducing the extent of fibrosis or eliminating the exudate-filled periprosthetic space around the implant that is prone to infection and/or chronic inflammation (McCurdy, 1990).

While capsular contracture is a challenge from a clinical standpoint (McCurdy, 1990), patient preference suggests that breast firmness is not a definitive factor in deciding which type of breast implant is preferred. Textured implants often have an unnatural “feel,” because textured implant shells lack flexibility (Caffee, 1994). A higher incidence of skin wrinkling over the breast also occurs with textured implants (McCurdy, 1990; Wong et al., 2006), presumably from tissue integration that immobilizes the implant and allows implant surface wrinkling to be more visible. This may be because smooth implants reside in a fluid-like periprosthetic pocket, reducing skin wrinkling as the implant is able to move within this space. Since implant feel and appearance are important patient considerations, smooth surface implants are often preferred by patients in the absence of significant contracture (Wong et al., 2006).

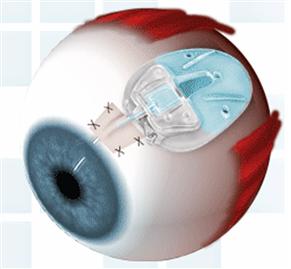

Texturing to Minimize Fibrotic Encapsulation of Glaucoma Drainage Devices

Glaucoma is the obstruction of aqueous drainage that causes the intraocular pressure (IOP) to increase to the point of nerve damage (Adatia and Damji, 2005). Treatment methods to decrease IOP include topical eye drops, surgery, and glaucoma drainage devices in refractory cases (Boswell et al., 1999; Ayyala et al., 2006). Glaucoma drainage devices (GDDs) are silicone tubes inserted into the anterior chamber of the eye. Attached to the tube is a plate that is sutured beneath the conjunctiva (Jacob et al., 1998) (Figure I.2.15.4). The plate becomes enclosed by a fibrous capsule 3–6 weeks post-operative, creating a “filtering bleb” (a small bubble) through which aqueous humor drains and is reabsorbed by the surrounding tissue (Jacob et al., 1998). Over two to four years, a thick fibrous capsule forms around the device, causing the filtering bleb to fail at least 20% of the time (Jacob et al., 1998). Encapsulation decreases absorption of the drained aqueous humor, leading to increased pressure in the anterior chamber (Boswell et al., 1999).

FIGURE I.2.15.4 Schematic of glaucoma drainage device placement in eye.

(Ahmed™ Glaucoma Valve glaucoma drain, New World Medical, Inc.)

Implant material, rigidity, flexibility, and shape (Ayyala et al., 2006) are potential contributors to long-term device failure. Micromotion of a smooth, rigid plate against the scleral surface has also been attributed to exacerbating scar tissue formation by causing constant, low-grade inflammation (Jacob et al., 1998; Ayyala et al., 2006). To reduce micromotion, porous plate designs (50 μm pore size silicone attached to smooth plate) were investigated to encourage fibrotic tissue anchorage of the implant (Jacob et al., 1998). However, this particular porous design has been linked with higher incidences of diplopia (double vision), possibly due to implant adhesion to the recti muscles and limiting bleb elevation compared with smooth designs (Ayyala et al., 2006).

Preliminary experiments in rabbits with ePTFE porous plates (60 μm pore size) found thinner, less dense, and more vascular capsules forming than around commercial, non-porous plates. This capsule provides less restriction to aqueous draining into the subconjuntival space, and the close proximity of microvessels also facilitates aqueous reabsorption (Boswell et al., 1999). Commercial GDDs enclosed in a two-layer ePTFE membrane have been reported to have minimal capsule thickness, with highly vascular tissue encasing the device after six weeks in rabbits (Ahmad et al., 2004). The smaller pores within the inner layer prevent cells from infiltrating the device lumen and valve or restricting aqueous humor outflow. The larger outer pore layer stimulates tissue integration and blood vessel formation adjacent to the device, as well as reducing capsule thickness (Ahmad et al., 2004).

Promoting Angiogenesis

Improving Long-Term Performance of Vascular Grafts

Synthetic vascular grafts are used to repair damaged or occluded blood vessels. For decades, researchers and manufacturers have been challenged to create synthetic grafts that mimic physiological function (Davids et al., 1999). Graft material porosity is related to graft healing (Wesolowski et al., 1961; Kuzuya et al., 2004), and is critical as part of the strategy to form a stable, endothelium-lined lumen to provide an anti-thrombotic surface that is similar to native vessels (Wesolowski et al., 1961; White et al., 1983; Clowes et al., 1986; Hirabayashi et al., 1992; Nagae et al., 1995). ePTFE and Dacron® (knitted and woven) are common synthetic graft materials (Nagae et al., 1995; Davids et al., 1999).

Numerous studies conclude that high porosity (≥60 μm pores) ePTFE small diameter grafts have superior graft healing compared to low porosity (≤30 μm pores) grafts (Hess et al., 1984; Branson et al., 1985; Golden et al., 1990; Hirabayashi et al., 1992; Nagae et al., 1995) in terms of patency as well as the rate, stability, and completeness of luminal endothelialization. Optimal pore size for achieving stable luminal endothelium coverage in small diameter grafts is 60 μm (Hess et al., 1989; Golden et al., 1990; Hirabayashi et al., 1992; Nagae et al., 1995; Miura et al., 2002). This pore size provides adequate porosity for transmural fibrovascular tissue ingrowth. Infiltrating capillaries from the surrounding tissue facilitate endothelialization and smooth muscle cell formation along the graft surface, forming the stable neointima (Davids et al., 1999). Dacron® has a greater prominence in large diameter grafts due to excessive graft surface thrombus. Typically, Dacron® graft lumens become coated in a thick, stable layer of fibrin which limits endothelialization and transmural tissue ingrowth (Davids et al., 1999) (see Chapter II.5.3.B for more discussion on vascular grafts).

Minimizing Infection and Epithelial Downgrowth

Percutaneous devices penetrate the body through a surgically created defect in the skin to provide a conduit between an implanted medical device or artificial organ and the extracorporeal space (von Recum, 1984; Yu et al., 1999). Percutaneous devices include catheters (i.e., peritoneal dialysis, intravascular), prosthetic attachments, dental implants, feeding and tracheal tubes, and needle-type glucose sensors (Fukano et al., 2006; Isenhath et al., 2007). However, breaking the skin barrier provides a route to infection and increases complications associated with wound non-closure (Yu et al., 1999). The incidence of catheter related bloodstream infections ranges between 80,000 and 250,000 annually in the USA, with health related expenses costing several billions of dollars (Isenhath et al., 2007).

Strategies to reduce percutaneous device-related infection involve antibiotics applied topically, administered prophylactically or incorporated into the device (Dasgupta, 2000; Fukano et al., 2006; Isenhath et al., 2007). Antibiotics, while clinically effective, raise concerns about the development of antibiotic-resistant strains (Dasgupta, 2000).

Percutaneous devices also fail from mechanical irritation (avulsion) or epithelial downgrowth that forms a pocket around the implant (marsupialization). Acute mechanical interfacial stresses tear the device from its implantation bed (von Recum, 1984), while chronic, small mechanical stresses cause localized injury, resulting in inflammation and increased susceptibility to infection (von Recum, 1984). Mechanical forces also prevent an epidermal seal from forming, increasing risk of infection (von Recum, 1984). Marsupialization occurs primarily around smooth implants, when epidermis surrounding the implant grows parallel to the implant surface and unites under the implant, surrounding the implant in an epidermal pocket. The percutaneous device has now become extracutaneous, and the tissue pocket becomes a source for infection since an epidermal seal has not formed between the implant and skin (von Recum, 1984).

Perimigration is the migration of epidermal cells into a porous material (von Recum, 1984). Competition between macrophages, giant cells, and fibroblasts within the pores prevents connective tissue maturation and scar tissue formation. The immature connective tissue soon becomes displaced by proliferating and maturing epidermal cells, possibly with assistance from enzymatic lysis. As the epidermal cells reach the underlying connective tissue bed, they begin to proliferate and form an epidermis-lined pocket around the percutaneous device, causing extrusion (von Recum, 1984).

Dermal integration is necessary to prevent infection, avulsion, and marsupialization, and to ensure the long-term performance of percutaneous devices (von Recum, 1984; Chehroudi and Brunette, 2002; Isenhath et al., 2007). Several porous and textured biomaterials have been investigated to improve percutaneous device performance and longevity. To reduce catheter exit-site infection, “cuffs” are attached to the catheter at the location where the external segment of catheter exits the body. These cuffs are implanted beneath the skin.

Dacron® velour cuffs are commonly used in commercial catheters (Dasgupta, 2000). These cuffs become fibrotically encapsulated, serving both to anchor the catheter and to provide a barrier for bacterial entry (Dasgupta, 2000). However, avascularity of the fibrotic tissue has been reported to encourage bacterial attachment in the tissue surrounding the catheter (Dasgupta, 2000). Microporous silicone cuffs have been shown to reduce exit site infection by 60% in canine models (Moncrief et al., 1995). The microporous structure encourages vascular tissue integration to facilitate immune cell surveillance at the exit site, as well as to reduce scar formation (Moncrief et al., 1995).

Microtexture and porous biomaterials have been shown to be effective in reducing infection, avulsion, and epithelial downgrowth in several animal models (Chehroudi and Brunette, 2002). Highly textured surfaces are reported to have significantly more tissue attachment, thinner capsules, and less tissue–implant separation compared to smooth surface implants (Kim et al., 2006). Grooved surfaces encourage random fibroblast orientation, lessening the effects of contractile forces that contribute to tissue–implant separation (Kim et al., 2006). In contrast, parallel collagen fibers against smooth surfaces create poorly integrated, avascular capsules prone to separation from the implant during wound contracture (Kim et al., 2006). Stable tissue attachment also reduces the effects of micromotion (Kim et al., 2006), minimizing avulsion risk. Capsule thickness appears to relate to the amount of mechanical stresses imparted on the implant (von Recum, 1984). Stability may also promote healing, and encourage thinner capsule formation (Kim et al., 2006).

Optimal pore size for tissue ingrowth is 40 μm or larger (Winter, 1974; von Recum, 1984; Isenhath et al., 2007; Fukano et al., 2010); however, pores as small as 3 μm have been observed with fibrous tissue ingrowth (Squier and Collins, 1981). Most rapid epithelium migration occurs during the first two weeks post-implantation, regardless of pore size (Squier and Collins, 1981). Following the initial two weeks, epithelial migration appears to be inversely related to pore size: increased endothelium downgrowth with decreased pore size (Squier and Collins, 1981). Speed of epithelial migration differs between species (Chehroudi and Brunette, 2002), for example migration in rodents is considerably faster than in humans (Chehroudi and Brunette, 2002). Porosity is also thought to be a key factor affecting the rate of migration (Squier and Collins, 1981), and is required for connective tissue and possibly epithelial ingrowth into percutaneous implants (Isenhath et al., 2007; Fukano et al., 2010).

While textured and porous surfaces encourage dermal integration, there are concerns that surfaces with irregular topologies may be more prone to harboring bacteria (Chehroudi and Brunette, 2002). Bacteria may out-compete tissue cells in adhering to an implant surface, thus preventing tissue integration and promoting infection. Future investigations to optimize topological properties to minimize bacterial contamination (Chehroudi and Brunette, 2002) are recommended.

Porous Coatings to Improve Glucose and Oxygen Transport to Implanted Sensors

Percutaneous glucose sensors must be removed after three to seven days to prevent host inflammation, wound healing, and subsequent foreign-body encapsulation from jeopardizing sensor reliability. The foreign-body response ultimately causes impedance of glucose and oxygen transport to the sensor, resulting in sensor signal deterioration, and frequently sensor failure. Methods that improve analyte (glucose, oxygen) transport to indwelling sensors could allow sensors to reliably measure interstitial glucose concentrations for several weeks, as opposed to days.

Attempts to improve long-term sensor performance have included surface chemical modification, various coatings (Gifford et al., 2005; Nablo et al., 2005; Shin and Schoenfisch, 2006), release of molecular mediators (Friedl, 2004; Ward et al., 2004; Norton et al., 2005), and surface topography (Wisniewski and Reichert, 2000; Wisniewski et al., 2000). The effect of surface texturing on the tissue that surrounds implanted biomaterials is well-documented for devices such as total joint arthroplasty (Bauer and Schils, 1999; Ryan et al., 2006) and percutaneous devices (Tagusari et al., 1998; Walboomers and Jansen, 2005; Kim et al., 2006).

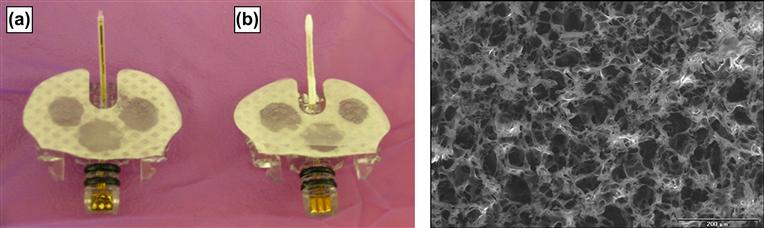

Topographical approaches for improving long-term sensor performance were first proposed by Woodward (1982), who suggested that the best coating for an implanted glucose sensor was a sponge that encourages tissue ingrowth and disrupts fibrosis (Figure I.2.15.5). Efforts to create tissue-modifying textured coatings for implantable sensors are attractive, because their impact is not dependent on a depletable drug reservoir, unlike drug eluting techniques.

FIGURE I.2.15.5 Example of a: (a) Medtronic MiniMed SOF-SENSOR™ glucose sensor; and (b) an experimental porous poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) coating applied to the sensor tip for investigational purposes. Inset: environmental scanning electron microscope image of porous PLLA coating fabricated using salt-leaching/gas foaming with ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3).

(Koschwanez, H. E. (2006). Unpublished data.) Courtesy of John Wiley and Sons.

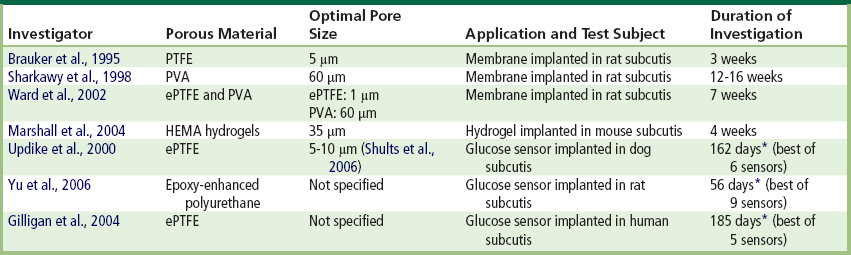

A significant range of materials and pore sizes are capable of promoting angiogenesis and reducing capsule thickness (Ward et al., 2002). Geometry, rather than chemical composition, of the material appears to determine biomaterial–microvasculature interactions (Brauker et al., 1995; Sieminski and Gooch, 2000). Table I.2.15.3 summarizes leading research in the area of porosity and porous coatings for glucose sensors, including the pore size reported to yield the greatest vascularization and/or the least capsule formation around the implant. Variations in pore size and pore structure in implanted biomaterials may, however, limit the conclusions that can be drawn about how pore size influences tissue response (Marshall et al., 2004).

TABLE I.2.15.3 Summary of Pore Sizes that Yielded Optimal Tissue Response (Promoted Angiogenesis and/or Reduced Capsule Thickness) Around Biomaterials or Glucose Sensors

NOTE: PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene), ePTFE (expanded polytetrafluoroethylene), PVA (polyvinyl alcohol), HEMA (hydroxyethyl methacrylate).

∗Maximum time sensor remained functional in vivo.

While porous biomaterials seemingly create the ideal environment for an indwelling glucose sensor, porous coatings applied to sensors have had less than ideal results. A critical factor in sensor failure in vivo is the fibrotic capsule that forms around glucose sensors (Dungel et al., 2008). Despite porous coatings stimulating the formation of vascular networks around glucose sensors in rats, newly formed vessels within porous coatings have been unable to overcome the diffusion barriers imparted by the collagen capsule (Dungel et al., 2008). Failing sensor sensitivity was found to correlate with increasing collagen deposition within the sponge implant (Dungel et al., 2008). Additionally, other factors, such as mechanical stresses imposed by the percutaneously implanted sensor, may have overshadowed the angiogenic-inducing, collagen-reducing properties of porous coatings (Koschwanez et al., 2008).

Recently, human studies (Gilligan et al., 2004) were performed using sensors covered with a porous angiogenic and bioprotective ePTFE membrane (Updike et al., 2000; Shults et al., 2006). Unfortunately, inflammation within the angiogenic layer in 80% of sensors, in addition to packaging failure in 60% of sensors, resulted in only 20% sensor survival after six months (Gilligan et al., 2004).

Conclusion

The use of textured and porous materials is widespread in medical device applications. Research and development on porous structures continues because of good clinical outcomes, important research findings, and a straightforward regulatory pathway. While a single pore size or textured morphology does not fit all applications, the majority of porous and textured biocompatible materials used in medical devices share the common characteristic of open architectures with interconnecting pores that support nutrient transfer, and promote cell migration and proliferation. Stable integration of the implant with the surrounding host tissue reduces irritation caused by micromotion, and promotes stable fibrovascular tissue ingrowth that promotes healing and minimizes infection.

Bibliography

1. Adatia FA, Damji KF. Chronic open-angle glaucoma: Review for primary care physicians. Canadian Family Physician. 2005;51:1229–1237.

2. Ahmad S, Lee M, Klitzman B, Olbrich K, Mordes D, et al. Comparison of Conventional Ahmed Implant With Newly Designed Valved Implant: A Pilot Study. Ft Lauderdale, FL: Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology; 2004.

3. Ayyala RS, Duarte JL, Sahiner N. Glaucoma drainage devices: State of the art. Expert Review of Medical Devices. 2006;3:509–521.

4. Bauer TW, Schils J. The pathology of total joint arthroplasty I Mechanisms of implant fixation. Skeletal Radiology. 1999;28:423–432.

5. Becker H, Springer R. Prevention of capsular contracture. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1999;103:1766–1768.

6. Benediktsson K, Perbeck L. Capsular contracture around saline-filled and textured subcutaneously-placed implants in irradiated and non-irradiated breast cancer patients: Five years of monitoring of a prospective trial. Journal of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery. 2006;59:27–34.

7. Bloebaum RD, Willie BM, Mitchell BS, Hofmann AA. Relationship between bone ingrowth, mineral apposition rate, and osteoblast activity. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2007;81A:505–514.

8. Bobyn JD, Pilliar RM, Cameron HU, Weatherly GC. The optimum pore-size for the fixation of porous-surfaced metal implants by the ingrowth of bone. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 1980:263–270.

9. Bobyn JD, Stackpool GJ, Hacking SA, Tanzer M, Krygier JJ. Characteristics of bone ingrowth and interface mechanics of a new porous tantalum biomaterial. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-British Volume. 1999;81B:907–914.

10. Boswell CA, Noecker RJ, Mac M, Snyder RW, Williams SK. Evaluation of an aqueous drainage glaucoma device constructed of ePTFE. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1999;48:591–595.

11. Branson DF, Picha GJ, Desprez J. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene as a microvascular graft: A study of 4 fibril lengths. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1985;76:754–763.

12. Brauker JH, Carrbrendel VE, Martinson LA, Crudele J, Johnston WD, et al. Neovascularization of synthetic membranes directed by membrane microarchitecture. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1995;29:1517–1524.

13. Bucky LP, Ehrlich HP, Sohoni S, May JW. The capsule quality of saline-filled smooth silicone, textured silicone, and polyurethane implants in rabbits: A long-term study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1994;93:1123–1131.

14. Burkhardt BR. Comparing contracture rates: Probability-theory and the unilateral contracture. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1984;74:527–529.

15. Burkhardt BR, Dempsey PD, Schnur PL, Tofield JJ. Capsular contracture: A prospective-study of the effect of local antibacterial agents. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1986;77:919–930.

16. Caffee HH. The effect of siltex texturing and povidone-iodine irrigation on capsular contracture around saline inflatable breast implants: Discussion. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1994;93:129–130.

17. Chalasani R, Poole-Warren L, Conway RM, Ben-Nissan B. Porous orbital implants in enucleation: A systematic review. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2007;52:145–155.

18. Chang YS, Oka M, Kobayashi M, Gu HO, Li ZL, et al. Significance of interstitial bone ingrowth under load-bearing conditions: A comparison between solid and porous implant materials. Biomaterials. 1996;17:1141–1148.

19. Chehroudi B, Brunette DM. Subcutaneous microfabricated surfaces inhibit epithelial recession and promote long-term survival of percutaneous implants. Biomaterials. 2002;23:229–237.

20. Chen GP, Ushida T, Tateishi T. Scaffold design for tissue engineering. Macromolecular Bioscience. 2002;2:67–77.

21. Clowes AW, Kirkman TR, Reidy MA. Mechanisms of arterial graft healing: Rapid transmural capillary ingrowth provides a source of intimal endothelium and smooth-muscle in porous PTFE prostheses. American Journal of Pathology. 1986;123:220–230.

22. Danino AM, Basmacioglu P, Saito S, Rocher F, Blanchet-Bardon C, et al. Comparison of the capsular response to the Biocell RTV and Mentor 1600 Siltex breast implant surface texturing: A scanning electron microscopic study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2001;108:2047–2052.

23. Dasgupta MK. Exit-site and catheter related infections in peritoneal dialysis: Problems and progress. Nephrology. 2000;5:17–25.

24. Davids L, Dower T, Zilla P. The lack of healing in conventional vascular grafts. In: Zilla P, Greisler HP, eds. Tissue Engineering of Vascular Prosthetic Grafts. Georgetown, TX: Landes Company; 1999.

25. de Pina MF, Ribeiro AI, Santos C. Epidemiology and Variability of Orthopaedic Procedures Worldwide. In: Bentley G, ed. European Instructional Lectures. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2011;9–19.

26. Dungel P, Long N, Yu B, Moussy Y, Moussy F. Study of the effects of tissue reactions on the function of implanted glucose sensors. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2008;85A:699–706.

27. Embrey M, Adams EE, Cunningham B, Peters W, Young VL, et al. A review of the literature on the etiology of capsular contracture and a pilot study to determine the outcome of capsular contracture interventions. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 1999;23:197–206.

28. Fagrell D, Berggren A, Tarpila E. Capsular contracture around saline-filled fine textured and smooth mammary implants: A prospective 7.5-year follow-up. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2001;108:2108–2112.

29. Friedl KE. Corticosteroid modulation of tissue responses to implanted sensors. Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics. 2004;6:898–901.

30. Fukano Y, Knowles NG, Usui ML, Underwood RA, Hauch KD, et al. Characterization of an in vitro model for evaluating the interface between skin and percutaneous biomaterials. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2006;14:484–491.

31. Fukano Y, Usui ML, Underwood RA, Isenhath S, Marshall AJ, et al. Epidermal and dermal integration into sphere-templated porous poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) implants in mice. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2010;94(4):1172–1186.

32. Gabriel SE, Woods JE, Ofallon M, Beard CM, Kurland LT, et al. Complications leading to surgery after breast implantation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336:677–682.

33. Gampper TJ, Khoury H, Gottlieb W, Morgan RF. Silicone gel implants in breast augmentation and reconstruction. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2007;59:581–590.

34. Gifford R, Batchelor MM, Lee Y, Gokulrangan G, Meyerhoff ME, et al. Mediation of in vivo glucose sensor inflammatory response via nitric oxide release. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2005;75A:755–766.

35. Gilligan B, Shults M, Rhodes RK, Jacobs PG, Brauker JH, et al. Feasibility of continuous long-term glucose monitoring from a subcutaneous glucose sensor in humans. Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics. 2004;6:378–386.

36. Goldberg RA, Dresner SC, Braslow RA, Kossovsky N, Legmann A. Animal-model of porous polyethylene orbital implants. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1994;10:104–109.

37. Golden MA, Hanson SR, Kirkman TR, Schneider PA, Clowes AW. Healing of polytetrafluoroethylene arterial grafts is influenced by graft porosity. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 1990;11:838–845.

38. Harris LD, Kim B-S, Mooney DJ. Open pore biodegradable matrices formed with gas foaming. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1998;42:396–402.

39. Hess F, Jerusalem C, Grande P, Braun B. Significance of the inner-surface structure of small-caliber prosthetic blood-vessels in relation to the development, presence, and fate of a neo-intima: A morphological evaluation. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1984;18:745–755.

40. Hess F, Steeghs S, Jerusalem C. Neointima formation in expanded polytetrafluoroethylene vascular grafts with different fibril lengths following implantation in the rat aorta. Microsurgery. 1989;10:47–52.

41. Hing KA, Best SM, Tanner KE, Bonfield W, Revell PA. Mediation of bone ingrowth in porous hydroxyapatite bone graft substitutes. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2004;68A:187–200.

42. Hirabayashi K, Saitoh E, Ijima H, Takenawa T, Kodama M, et al. Influence of fibril length upon ETFE graft healing and host modification of the implant. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1992;26:1433–1447.

43. Hutmacher DW. Scaffolds in tissue engineering bone and cartilage. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2529–2543.

44. Isenhath SN, Fukano Y, Usui ML, Underwood RA, Irvin CA, et al. A mouse model to evaluate the interface between skin and a percutaneous device. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2007;83A:915–922.

45. Jacob JT, Burgoyne CF, Mckinnon SJ, Tanji TM, Lafleur PK, et al. Biocompatibility response to modified Baerveldt glaucoma drains. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1998;43:99–107.

46. Karageorgiou V, Kaplan D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5474–5491.

47. Kienapfel H, Sprey C, Wilke A, Griss P. Implant fixation by bone ingrowth. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 1999;14:355–368.

48. Kim H, Murakami H, Chehroudi B, Textor M, Brunette DM. Effects of surface topography on the connective tissue attachment to subcutaneous implants. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2006;21:354–365.

49. Klawitter JJ, Bagwell JG, Weinstein AM, Sauer BW, Pruitt JR. Evaluation of bone-growth into porous high-density polyethylene. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1976;10:311–323.

50. Koschwanez HE, Yap FY, Klitzman B, Reichert WM. In vitro and in vivo characterization of porous poly-L-lactic acid coatings for subcutaneously implanted glucose sensors. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2008;87A:792–803.

51. Kuster M. Exercise recommendations after total joint replacement: A review of the current literature and proposal of scientifically based guidelines. Sports Medicine. 2002;32:433–445.

52. Kuzuya A, Matsushita M, Oda K, Kobayashi M, Nishikimi N, et al. Healing of implanted expanded polytetrafluoroethylene vascular access grafts with different internodal distances: A histologic study in dogs. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2004;28:404–409.

53. Malata CM, Feldberg L, Coleman DJ, Foo ITH, Sharpe DT. Textured or smooth implants for breast augmentation? Three year follow-up of a prospective randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 1997;50:99–105.

54. Marshall AJ, Irvin CA, Barker T, Sage EH, Hauch KD, et al. Biomaterials with tightly controlled pore size that promote vascular in-growth. Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society. 2004;228 U386–U386.

55. McCurdy JA. Relationships between spherical fibrous capsular contracture and mammary prosthesis type: A comparison of smooth and textured implants. American Journal of Cosmetic Surgery. 1990;7:235–238.

56. Mikos AG, Bao Y, Cima LG, Ingber DE, Vacanti JP, et al. Preparation of poly(glycolic acid) bonded fiber structures for cell attachment and transplantation. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1993;27:183–189.

57. Mikos AG, Thorsen AJ, Czerwonka LA, Bao Y, Langer R, et al. Preparation and characterization of poly(l-lactic acid) foams. Polymer. 1994;35:1068–1077.

58. Miura H, Nishibe T, Yasuda K, Shimada T, Hazama K, et al. The influence of node-fibril morphology on healing of high-porosity expanded polytetrafluoroethylene grafts. European Surgical Research. 2002;34:224–231.

59. Moncrief J, Popovich R, Seare W, Moncrief D, Simmons V, et al. A new porous surface modification technology for peritoneal dialysis catheters as an exit-site cuff to reduce exit-site infections. Advances in Peritoneal Dialysis. 1995;11:197–199.

60. Mooney DJ, Baldwin DF, Suh NP, Vacanti JP, Langer R. Novel approach to fabricate porous sponges of poly(-lactic-co-glycolic acid) without the use of organic solvents. Biomaterials. 1996;17:1417–1422.

61. Nablo BJ, Prichard HL, Butler RD, Klitzman B, Schoenfisch MH. Inhibition of implant-associated infections via nitric oxide. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6984–6990.

62. Nagae T, Tsuchida H, Peng SK, Furukawa K, Wilson SE. Composite porosity of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene vascular prosthesis. Cardiovascular Surgery. 1995;3:479–484.

63. Nam YS, Yoon JJ, Park TG. A novel fabrication method of macroporous biodegradable polymer scaffolds using gas foaming salt as a porogen additive. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2000;53:1–7.

64. Norton LW, Tegnell E, Toporek SS, Reichert WM. In vitro characterization of vascular endothelial growth factor and dexamethasone releasing hydrogels for implantable probe coatings. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3285–3297.

65. Pennisi VR. Long-term use of polyurethane breast prostheses: A 14-year experience. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1990;86:368–371.

66. Pollock H. Breast capsular contracture: A retrospective study of textured versus smooth silicone implants. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1993;91:404–407.

67. Raykhlin NT, Kogan AK. The development and malignant degeneration of the connective tissue capsules around plastic implants. Prob Oncol. 1961;7:11–14.

68. Rosengren A, Danielsen N, Bjursten LM. Reactive capsule formation around soft-tissue implants is related to cell necrosis. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1999;46:458–464.

69. Rubin PAD, Popham JK, Bilyk JR, Shore JW. Comparison of fibrovascular ingrowth into hydroxyapatite and porous polyethylene orbital implants. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1994;10:96–103.

70. Ryan G, Pandit A, Apatsidis DP. Fabrication methods of porous metals for use in orthopaedic applications. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2651–2670.

71. Salzmann DL, Kleinert LB, Berman SS, Williams SK. The effects of porosity on endothelialization of ePTFE implanted in subcutaneous and adipose tissue. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1997;34:463–476.

72. Sami D, Young S, Peterson R. Perspective on orbital enucleation implants. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2007;52:244–265.

73. Schugens C, Maquet V, Grandfils C, Jerome R, Teyssie J. Polylactide macroporous biodegradable implants for cell transplantation II Preparation of polylactide foams by liquid–liquid phase separation. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1996a;30:449–461.

74. Schugens C, Maquet V, Grandfils C, Jerome R, Teyssie P. Biodegradable and macroporous polylactide implants for cell transplantation 1 Preparation of macroporous polylactide supports by solid–liquid phase separation. Polymer. 1996b;37:1027–1038.

75. Sharkawy AA, Klitzman B, Truskey GA, Reichert WM. Engineering the tissue which encapsulates subcutaneous implants 1 Diffusion properties. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1997;37:401–412.

76. Sharkawy AA, Klitzman B, Truskey GA, Reichert WM. Engineering the tissue which encapsulates subcutaneous implants II Plasma-tissue exchange properties. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1998;40:586–597.

77. Shin JH, Schoenfisch MH. Improving the biocompatibility of in vivo sensors via nitric oxide release. Analyst. 2006;131:609–615.

78. Shults MC, Updike SJ, Rhodes RK. Device and method for determining analyte levels. US Patent No 7110803 2006.

79. Sieminski AL, Gooch KJ. Biomaterial-microvasculature interactions. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2233–2241.

80. Simske SJ, Ayers RA, Bateman TA. Porous materials for bone engineering. Materials Science Forum. 1997;250:151.

81. Squier CA, Collins P. The relationship between soft-tissue attachment, epithelial downgrowth and surface porosity. Journal of Periodontal Research. 1981;16:434–440.

82. Sun LM, Berndt CC, Gross KA, Kucuk A. Material fundamentals and clinical performance of plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings: A review. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2001;58:570–592.

83. Tagusari O, Yamazaki K, Litwak P, Kojima A, Klein EC, et al. Fine trabecularized carbon: Ideal material and texture for percutaneous device system of permanent left ventricular assist device. Artificial Organs. 1998;22:481–487.

84. Tarpila E, Ghassemifar R, Fagrell D, Berggren A. Capsular contracture with textured versus smooth saline-filled implants for breast augmentation: A prospective clinical study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1997;99:1934–1939.

85. Taylor SR, Gibbons DF. Effect of surface texture on the soft-tissue response to polymer implants. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1983;17:205–227.

86. Turner TM, Sumner DR, Urban RM, Rivero DP, Galante JO. A comparative-study of porous coatings in a weight-bearing total hip-arthroplasty model. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American Volume). 1986;68A:1396–1409.

87. Updike SJ, Shults MC, Gilligan BJ, Rhodes RK. A subcutaneous glucose sensor with improved longevity, dynamic range, and stability of calibration. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:208–214.

88. von Recum AF. Applications and failure modes of percutaneous devices: A review. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1984;18:323–336.

89. Walboomers XF, Jansen JA. Effect of microtextured surfaces on the performance of percutaneous devices. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2005;74A:381–387.

90. Ward WK, Slobodzian EP, Tiekotter KL, Wood MD. The effect of microgeometry, implant thickness and polyurethane chemistry on the foreign body response to subcutaneous implants. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4185–4192.

91. Ward WK, Wood MD, Casey HM, Quinn MJ, Federiuk IF. The effect of local subcutaneous delivery of vascular endothelial growth factor on the function of a chronically implanted amperometric glucose sensor. Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics. 2004;6:137–145.

92. Wesolowski SA, Fries CC, Karlson KE, Debakey M, Sawyer PN. Porosity: Primary determinant of ultimate fate of synthetic vascular grafts. Surgery. 1961;50:91–96.

93. Whang K, Thomas CH, Healy KE, Nuber G. A novel method to fabricate bioabsorbable scaffolds. Polymer. 1995;36:837–842.

94. White R, Goldberg L, Hirose F, Klein S, Bosco P, et al. Effect of healing on small internal diameter arterial graft compliance. Biomaterials Medical Devices and Artificial Organs. 1983;11:21–29.

95. Winter GD. Transcutaneous implants: Reactions of skin–implant interface. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1974;8:99–113.

96. Wisniewski N, Reichert M. Methods for reducing biosensor membrane biofouling. Colloids and Surfaces B-Biointerfaces. 2000;18:197–219.

97. Wisniewski N, Moussy F, Reichert WM. Characterization of implantable biosensor membrane biofouling. Fresenius Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 2000;366:611–621.

98. Wong CH, Samuel M, Tan BK, Song C. Capsular contracture in subglandular breast augmentation with textured versus smooth breast implants: A systematic review. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;118:1224–1236.

99. Woodward SC. How fibroblasts and giant-cells encapsulate implants: Considerations in design of glucose sensors. Diabetes Care. 1982;5:278–281.

100. Wu BM, Borland SW, Giordano RA, Cima LG, Sachs EM, et al. Solid free-form fabrication of drug delivery devices. Journal of Controlled Release. 1996;40:77–87.

101. Yang SF, Leong KF, Du ZH, Chua CK. The design of scaffolds for use in tissue engineering Part 1 Traditional factors. Tissue Engineering. 2001;7:679–689.

102. Yu BZ, Long N, Moussy Y, Moussy F. A long-term flexible minimally-invasive implantable glucose biosensor based on an epoxy-enhanced polyurethane membrane. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2006;21:2275–2282.

103. Yu C, Sun Y, Bradfield J, Fiordalisi I, Harris GD. A novel percutaneous barrier device that permits safe subcutaneous access. Asaio Journal. 1999;45:531–534.