Chapter I.2.16

Electrospinning Fundamentals and Applications

Motivation For Using Electrospun Membranes

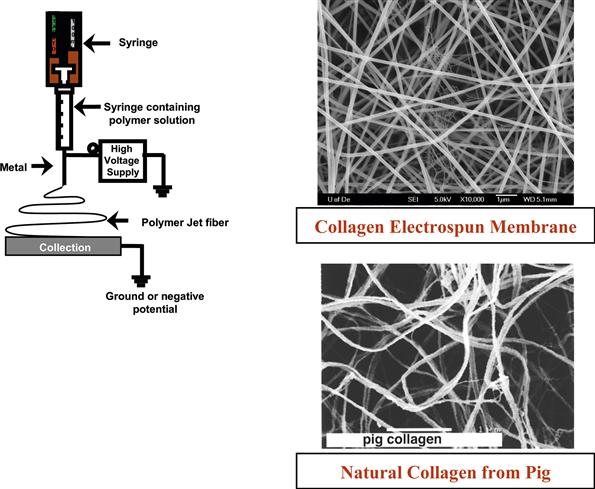

Electrospinning is an excellent candidate process for producing tissue engineering and vascular graft constructs, since the resulting electrospun materials possess many of the desired properties appropriate for successful cell and tissue growth, such as a high surface-to-volume ratio and an interconnected three-dimensional porous network (Table I.2.16.1). It is a simple and robust method to produce micro- and nanometer diameter fibers, and can be thought of as a biomimetic process since the materials produced resemble the nanoscale architecture of extracellular matrix (ECM) (Figure I.2.16.1), and can promote and enhance biological activities. The experimental arrangement generally consists of a pipette or syringe with a blunt needle, which is filled with a polymer solution or melt. An electrode from a high voltage power supply (0–30 kV) is placed in contact with the solution and an electric field is applied.

TABLE I.2.16.1 List of Desired Properties of Tissue Engineering Constructs

| Desired Properties | Electrospinning |

| Interconnected porous network | Yes |

| Large void volume (cell seeding and penetration) | Yes |

| Large surface-to-volume ratio | Yes |

| Specific surface chemistry and surface microstructure | Yes |

| Mechanical strength (comparable to physiological stresses) | Yes |

| Controlled degradation rate (matches tissue regeneration) | Yes |

| Incorporation of growth factors | Yes |

FIGURE I.2.16.1 Schematic of electrospinning set up and field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) micrographs comparing an electrospun collagen fibrous membrane with natural collagen fibrils obtained from a pig ECM. (Gemmell et al., 1995)

The electric charge overcomes the surface tension of the solution droplet, and a single fiber in the form of a jet is emitted. The jet is collected on a counter electrode in the form of a nonwoven fibrous mat (Figure I.2.16.1). The fibers produced are generally 100–400 nm in diameter, but the size of the fibers can easily be changed through variations in the processing parameters, such as applied electric field strength and solute concentrations (Doshi and Reneker, 1995). In addition, a wide variety of polymers that are desirable for tissue engineering applications have been electrospun. These include collagen, poly(lactic acid)/poly(glycolic acid), and their copolymers, fibrinogen, elastin, and spider silk (Matthews et al., 2002; Stephens et al., 2003; Boland et al., 2004; Shields et al., 2004).Coupling the ability to control the fiber size within a matrix with the ability to choose a variety of polymers with different physical/chemical/mechanical properties will make it possible to create a construct that has comparable properties to a specific tissue. Another desirable aspect of electrospinning is that only a small amount of starting material (<50 mg) is required compared to more traditional fiber formation methods (10–20 pounds). This becomes critically important for next generation materials, such as biopolymers like spider-silk and those synthesized in small-scale laboratory preparations, because they are generally produced in small quantities (milligrams). Recent attempts to scale-up the electrospinning process using a multiple jet system have shown considerable promise (see for example Elmarco at www.elmarco.com), and in the near future useful materials for transfer to the clinical environment will be developed.

Historical Perspective

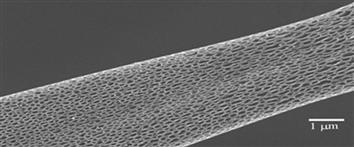

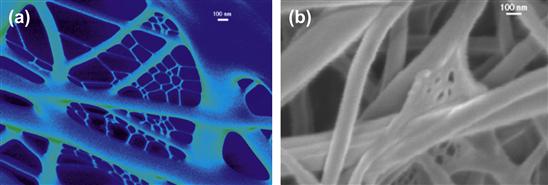

Electrospinning has been around for more than a century, first invented by Formhals in 1934 and improved by different research groups over the years. Many polymers have been routinely electrospun, and several review articles summarizing these techniques have appeared (for example, see Greiner and Wendorff, 2007). Unique micro- and nanoscale features on the surface of polymer fibers have been produced at the University of Delaware using the electrospinning process. These features are advantageous for tissue engineering and filtration applications because they provide an increase in surface area and roughness. Surface textures, in the form of micro- and nanopores, can be formed on the surface of fibers electrospun from volatile solvents. Pores ranging in size from 20–1000 nm (having depths ranging from 50–70 nm) have been observed on the surface of several amorphous and semicrystalline polymer fibers, such as polystyrene (PS), poly(methylmethacrylate) (PMMA), PC, and poy(ethylene oxide) (PEO) (Megelski et al., 2002; Casper et al., 2004) (see Figure I.2.16.2). As we further optimized the processing protocols for electrospinning fibers we observed that, with a judicious choice of electrospinning parameters and solvent, nanoweb structures (Stephens et al., 2003) could also be produced. Nanowebs are composed of small fibrils (~10–15 nm) that interconnect the larger fibers (~70–100 nm) of the electrospun mat to produce a web-like structure that is similar in appearance to that produced by the spider. These fibrillar nanowebs have been observed in several different types of polymers and bioderived materials (collagen, denatured collagen, spider silk, nylon) two examples of which are shown in Figure I.2.16.3. We have identified the processing parameters and the mechanisms that cause the surface texturing and nanowebs to form, and this has provided us with the ability to produce fibers and fiber mats with the desired features for different applications. For example, in Figure I.2.16.3, the electrospinning conditions to promote (Stephens et al., 2003) the formation of nanowebs were the following: Figure I.2.16.3(a) collagen (type I) at 30 wt% from formic acid, 23 gauge needle, 10 cm syringe to counter-electrode gap, 7 kV; and Figure I.2.16.3(b) synthetic spider silk at 20 wt%, 23 gauge needle, 10 cm gap, 7 kV.

FIGURE I.2.16.2 Micro- and nanotextured electrospun fibers; PS electrospun from tetrahydrofuran (THF).

FIGURE I.2.16.3 Nanowebs formed by electrospinning: (a) collagen; (b) spider silk.

In addition, we have also demonstrated that electrospun fibers can be functionalized with macromolecules that may improve the patency of vascular graft materials. Specifically, four-arm star-shaped poly(ethylene glycol) PEG polymers with termini derivatized with low molecular weight heparin (PEG-LMWH) have been incorporated into electrospun fibers comprised of either poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) or poly(lactic-glycolic acid) PLGA. The synthesis of the PEG-LMWH star bioconjugate and its incorporation into biopolymeric fibers offers opportunities for the production of fibrous materials capable of local and sustained release of therapeutically relevant proteins.

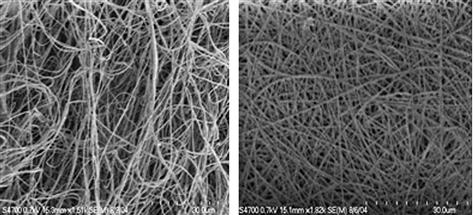

The PEG-LMWH can be easily incorporated into fibrous matrices via electrospinning protocols, which has been demonstrated (Casper et al., 2005) with PEO and PLGA fibers. The concentration of the polymeric solutions used during electrospinning varied depending on the carrier polymer employed, but in both cases, PEG-LMWH was easily incorporated into fibers without altering the fiber size or shape (Figure I.2.16.4). PEO (Mw = 300,000 g/mol) was used at a 10 wt% concentration in water, and a flow rate of 0.07 mL/min was employed. PLGA (75:25, Mw = 90,000–126,000 g/mol) solutions were made at a 45 wt% concentration in dimethylformamide (DMF) and required a flow rate of 0.26 mL/hr.

FIGURE I.2.16.4 FE-SEM micrographs of electrospun PLGA (left) and PEG-LMWH/PLGA (right). Fiber diameters range from 200 nm to 1 micron. (Casper et al., 2005.)

Scanning electron microscopy confirmed that the incorporation of the PEG-LMWH did not alter fiber morphology (Figure I.2.16.4). Multiphoton microscopy of fibers electrospun with fluorescently labeled PEG-LMWH confirmed the presence of LMWH throughout the depth of the electrospun matrix. Toluidine blue spectrophotometric assays that detect heparin were used to determine that the amount of LMWH per mg of fibers was in the range of 3.5–85 μg, depending on the sample examined. Although both LMWH and PEG-LMWH can be processed into fibers, the incorporation of PEG-LMWH resulted in functional advantages such as improved growth factor binding, which likely results from improvements in retention of the PEG-LMWH in the fibers over the LMWH alone. The PEG-LMWH is retained in the fibers for at least 14 days, in contrast to LMWH, which is almost completely released from the fibers after 24 hours. A slower release of PEG-LMWH, and any bound growth factors, would allow for drug delivery over a period of time that would more closely match the timescales needed for cell proliferation, for example, along the inner surface of a vascular graft.

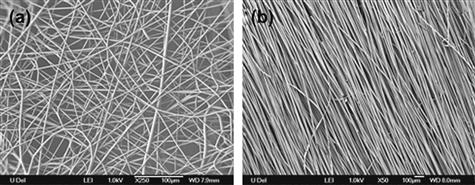

It is sometimes advantageous to macroscopically align the polymer fibers, since some mechanical and optical properties of the material can be improved. Shown in Figure I.2.16.5 are FE-SEM images of an isotropic polymer fibrous mat collected on a metallic plate (Figure I.2.16.5(a)) and fibers that have been wound up on a grounded rotating mandrel (Figure I.2.16.5(b)). In addition to the obvious fiber alignment that may improve properties, it has been demonstrated that fiber alignment can influence cell phenotype, an observation that will be illustrated in more detail later in this chapter.

FIGURE I.2.16.5 FE-SEM images of two sets of electrospun fibers: (a) isotropically oriented nylon 6 fibers (Lee et al., 2008); (b) aligned polystyrene fibers.

(Mandrel assembly courtesy of Vahik Krikorian.)

Characterization Methods

The application of standard confocal fluorescence and electron microscopic characterization of electrospun membranes provides facile determination of the extent of fiber orientation, diameter, and surface/interior functionalization. However, the functionality of polymer nanofibers is critically dependent on the macromolecular structure at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. Also, backbone orientation and potential changes in structure during dynamic deformation in the electrospinning process impact nanofiber functionality. The various forms of vibrational spectroscopy and wide angle X-ray diffraction employed in routine characterization studies of polymers also play a key role in understanding the structure/property relationships in polymer nanofibers.

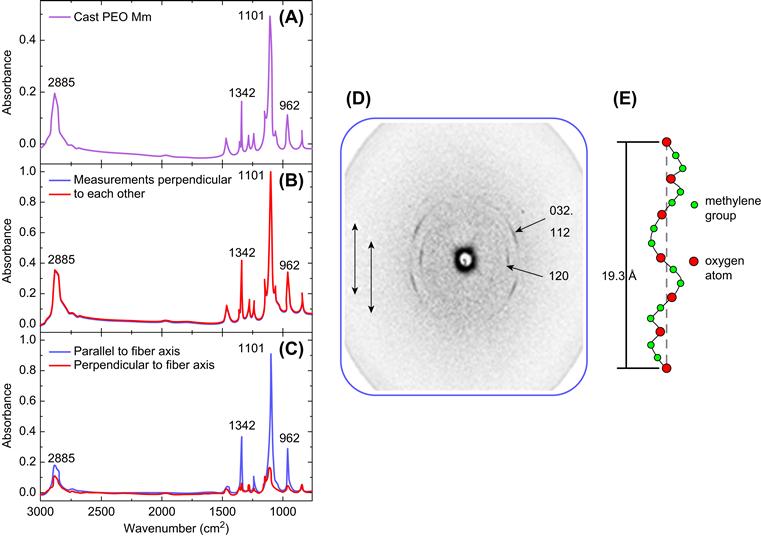

The extent of macroscopic orientation of electrospun micro- and nanoscale diameter fibers can be designed into the fibrous mat by electric field assisted fiber collection, by controlling the wind-up speed of the mandrel relative to the fiber spinning speed, by using a specially designed “banded” rod for collection, and by translating the rotating mandrel at various speeds during the collection process. If, in addition, the molecular orientation of the polymer backbone with respect to the fiber axis is controlled simultaneously, then it should be possible to use fiber orientation to optimize mechanical properties (compliance, modulus, tenacity, etc.). In order to assess the amount of molecular orientation within fibers, polarized Raman scattering (Frisk et al., 2004) can also be used in addition to the fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and X-ray diffraction methods illustrated in Figure I.2.16.6. It is possible to estimate the extent of polymer backbone alignment in the case of uniaxially oriented samples, such as fibers, using experimental quantities obtained by employing a combination of different polarization directions and sample orientation. These procedures can be used to determine an orientation distribution function (Kakade et al., 2007). We have successfully carried out such studies (Kakade et al., 2007) on a number of synthetic polymers (e.g., polyethylene, poly(ethylene terephthalate), and poly(trimethylene terephthalate)) and the experimental and theoretical protocols can easily be adapted to the study of biopolymers, such as collagen, PLGA/PEG-LMWH, and elastin electrospun fibers, in order to correlate processing conditions with extent of backbone orientation, which in turn will correlate with mechanical properties.

FIGURE I.2.16.6 (A) A typical FTIR spectra of pure PEO cast film; (B) polarized FTIR spectra for isotropic PEO fibrous mat show that the peak intensities for measurements parallel to fiber axis were very similar to the perpendicular measurements; (C) polarized FTIR spectra for uniaxially oriented PEO nanofibers show that the peak intensities for measurements parallel to fiber axis were greater compared to the perpendicular measurements; (D) wide-angle X-ray diffraction pattern of PEO nanofibers with the arrows indicating the direction of the fiber axis and the numbers indicating crystal planes in the reciprocal lattice; (E) a schematic of the PEO 7/2 helix indicating its orientation along the fiber axis.

As shown also in Figure I.2.16.6(D), wide angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) is also useful in determining molecular orientation in macroscopic polymer nanofibers. Instead of the ring pattern indicative of randomly oriented crystallites, intense arcs are observed in the PEO electrospun fibers collected on a charged plate. By indexing the crystal planes in the reciprocal lattice, it was possible to ascertain that the polymer chains are oriented parallel to the fiber axis and that the PEO backbone maintains its 7/2 helical conformation, confirming the results obtained by polarized FTIR and Raman spectroscopy. Studies on Nylon 6 nanofibers produced by electrospinning using an atomic force microscopy (AFM) tip and collected on a charged plate also showed molecular orientation relative to the fiber axis (Gururajan et al., 2011). This molecular alignment will produce improved mechanical, optical, and electrical properties.

Biomedical Applications for Electrospun Materials

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine

Tissue engineering (TE) is an emerging strategy in the broader field of regenerative medicine (RM) (see Section II.6, “Applications of Biomaterials in Functional Tissue Engineering”). In TE/RM, living cells are employed in the construction of de novo tissues for use as implants, diagnostic testing devices, and translational research models. Biomaterials of different types are used to support cellularized constructs. The development and implementation of TE/RM strategies, therefore, involve engineering cells and cell scaffolds to direct the organization and function of biological–material composites to desired ends. Electrospun materials have several attributes that recommend them as platforms for TE/RM approaches:

• Fibers can be prepared from a variety of natural and synthetic polymers that are biocompatible, amenable to surface modification with bioactive molecules, and capable of directing cell attachment and growth.

• The small diameter filaments within electrospun scaffolds mimic the fibrous architecture of native extracellular matrix.

• Composite materials can be prepared wherein biologically-active molecules are enmeshed in the fibrous matrix.

• Scaffolds can be engineered with desirable physical characteristics, such as stiffness.

• Materials can be designed to biodegrade over desired timescales.

• Scaffolds can be prepared with extensive networks of inter-connected pores that allow cell invasion into three-dimensional constructs and the subsequent perfusion of neo-tissues.

The physical and chemical characteristics of electrospun materials can be manipulated during production in order to control subsequent interactions between the produced scaffold and cells of different types. Materials can be designed to act as barriers to block cell penetration or as scaffolds to promote cell adhesion and migration, and to enable the diffusion of nutrients and wastes (for examples, see references Lu and Mikos, 1996; Riboldi et al., 2005; Zong et al., 2005). The specifics of cell–material interactions are of critical concern, and the adhesion, growth, organization, and biomolecular characteristics of cells on scaffolds are important biological parameters to consider in developing TE/RM strategies.

Electrospinning has been explored as a strategy to engineer a number of tissues including vasculature (Xu et al., 2004; Inoguchi et al., 2007), nerve (Prabhakaran et al., 2009), bone (Liu et al., 2009), and ligament/tendon (Ouyang et al., 2003; Bashur et al., 2009; Inanc et al., 2009). Many types of polymers have been employed in these early TE/RM efforts including poly(l-lactide), PLGA, PEO, polycaprolactone, polyurethane, polyethylene glycol, different types of collagen, elastin, hyaluronic acid, chitosan, fibroin, and combinations of these, to name a few. The selection of polymer and the specific conditions for electrospinning are motivated by the design characteristics of the finished product, and there are many choices and variations that can be employed. In general, the chemical nature of electrospun fibers can be varied across a broad range by altering polymer selection and production conditions.

In conjunction with the chemical characteristics of electrospun fibers, the physical characteristics of electrospun fiber scaffolds are also important. The porosity of scaffolds, which impacts cell penetration (Heydarkhan-Hagvall et al., 2008), fiber diameter, which affects cell morphology and phenotype (Yang et al., 2005), and the lateral alignment of fibers, which impacts cell morphology and local cell–cell interactions (Chew et al., 2008; Rockwood et al., 2008; Bashur et al., 2009), are all important determinants of tissue organization and function. These three parameters are inter-related, and in combination they may have complex effects on cultured cells. For example, suitable scaffold porosity in combination with appropriate polymer composition improves the three-dimensional migration of adipocyte-derived stem cells into composite gelatin/PCL scaffolds (Heydarkhan-Hagvall et al., 2008). In experiments to study the effects of both fiber alignment and fiber diameter on neural stem cells (NSCs), it was found that culture on anisotropic materials with aligned poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) fibers resulted in directed neurite outgrowth of significantly greater length than those found on cells cultured using isotropic PLLA scaffolds (Yang et al., 2005). In addition, the NSCs differentiated more readily on nanofibers when compared to the same cells grown on microfibers; this effect was independent of fiber alignment (Yang et al., 2005). In general, structural anisotropy and the diameter of filaments in fibrous scaffold materials may profoundly affect the activity of cells from other tissues as well.

In other work looking at aligned fibers, experiments using human ligament fibroblasts have shown that cells synthesize significantly more collagen when grown on aligned scaffolds versus randomly oriented nanofibers (Lee et al., 2005). Studies with Schwann cells grown on aligned electrospun polycaprolactone (ES-PCL) scaffolds indicated that culture on nanofibrous supports can improve cell maturation, with aligned scaffolds providing the greatest degree of maturation (Chew et al., 2008). Similarly, electrospun polyurethane (ES-PU) of different types has also been used to study the engineering of ligament-like tissues (Bashur et al., 2009) and myocardial-like tissues (Rockwood et al., 2008); in both these cases, culture on the aligned ES-PU substrata resulted in a more mature cellular phenotype.

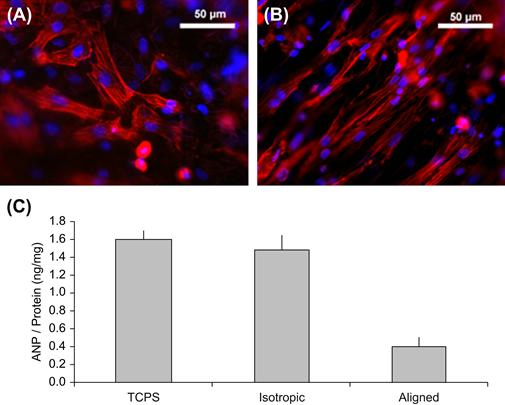

In our laboratories, we have investigated the effects of ES-PU anisotropy on the phenotype of heart cells. One of the critical but sometimes underappreciated functions of the heart is to release neurohormones such as atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP). ANP production and secretion by heart muscle cells are highly controlled, and an increased level of ANP in the blood has dramatic physiologic impact, resulting in a decrease in circulating blood volume. We found that the organization of ES-PU substrata had a profound effect on ANP production and release (Rockwood et al., 2008). As shown in Figure I.2.16.7, when identical cells were grown on anisotropic versus isotropic ES-PU, ANP production was significantly attenuated in the aligned ES-PU group. This attenuation is similar to that seen in three-dimensional culture (Akins et al., 2009), and occurred in cells that maintained the levels of other molecular markers for cardiac muscle. These results indicate a specific and significant change in cell phenotype associated with substrate alignment.

FIGURE I.2.16.7 (A) Primary heart cells grown on isotropic ES-PU. Cardiac muscle cells appear red (anti-sarcomeric myosin immunofluorescence) and nuclei appear blue (Hoechst 33258 dye). (B) Primary heart cells grown on aligned ES-PU. (C) Cellular ANP levels for cells grown on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS), isotropic ES-PU, and aligned ES-PU. Data are mean ± S.D., n = 3. (Akins et al., 2009).

The specific mechanisms by which ES fiber orientation impacts cell organization and function may differ from system to system, but cellular effects associated with electrospun support materials are likely related to differences in cell morphology and the altered interactions among neighboring cells. In particular, cells grown on oriented fibers tend to be more elongated with a spindle-like shape than cells grown on isotropic supports. In addition, anisotropic materials tend to be laterally aligned with significant cell–cell contacts along the length of neighboring cells. The ability to impact cell organization and function by engineering the physical and chemical characteristics of electrospun scaffolds is a powerful technology in nascent TE/RM approaches.

Drug Delivery

Another potent use for electrospun materials is in the area of drug and biomolecule delivery. Electrospun materials are amenable to surface modification with bioactive molecules, and it is possible to enmesh compounds into matrices during production (see discussion earlier in this chapter). This flexibility allows engineers to incorporate therapeutic compounds into implant materials to benefit patients or to include biomolecules in electrospun scaffolds to influence cells in tissue engineered constructs. Drug delivery strategies employing electrospun materials are being developed for both these applications. Examples of drug delivery approaches using electrospun materials include the introduction of antibiotics (Bolgen et al., 2007), anti-tumor drugs (Xie and Wang, 2006), bioactive proteins (Kim et al., 2007), and DNA (Nie and Wang, 2007). Applications employing antibiotics or DNA illustrate some key concepts.

Several groups have investigated the potential use of electrospun mats for the local delivery of antibiotics. The high surface area-to-volume ratios of these materials allows for extensive drug loading. Different approaches can be used to incorporate drugs into electrospun mats; mats can be prepared and then coated with the desired agent or the agent can be included with the polymer solution prior to electrospinning. The former approach has been applied to absorb polycaprolactone (PCL) membranes with a commercial antibiotic for use in preventing post-surgical abdominal adhesions in an animal model (Bolgen et al., 2007). The investigators found that approximately 80% of the antibiotic was released from the PCL within 3 hours, with the remaining amount released within 18 hours; however, the PCL scaffold remained in place substantially longer. The antibiotic-soaked PCL was effective in limiting adhesions, and exhibited improved healing compared to the control and to PCL mats without antibiotic.

An alternative approach using PLGA-based electrospun mats in which a different antibiotic was added to the pre-spun polymer solution found that incorporation of the drug yielded more consistent fibers with a decreased fiber diameter (Kim et al., 2004). The change in fiber diameter and morphology was likely a result of changes in the charge characteristics of the polymer/drug solution. The activity of the antibiotic was retained throughout the solvation and spinning processes. Interestingly, the inclusion of PEG-PLA block copolymer into the PLGA backbone allowed the amount of antibiotic embedded in the nanofibers to be increased, due to the altered hydrophilicity of the material.

The inclusion of DNA in composite scaffolds containing PLGA and hydroxyapatite has been used as a strategy to deliver plasmids containing bone morphogenetic protein gene sequences in efforts to augment bone tissue regeneration (Nie and Wang, 2007). The DNA is taken up by cells and the encoded protein expressed. It was found that higher relative amounts of hydroxyapatite in the scaffold resulted in faster DNA release from the material; perhaps due to the hydrophilicity of the components. These results further emphasize the need to understand the interactions between electrospun materials and the molecule to be delivered in the development of drug delivery approaches.

Summary

Electrospinning provides a facile method to fabricate porous and fibrous biomaterials from many different starting polymers. The fiber size can be comparable to that found in ECM. The ability to control fiber spacing and orientation permits material to be optimized for specific applications. Applications in tissue engineering and drug delivery are envisioned.

Bibliography

1. Akins RE, Rockwood D, Robinson KG, Sandusky D, Rabolt J, et al. Three-dimensional culture alters primary cardiac cell phenotype. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2009;16(2):629–641.

2. Bashur CA, Shaffer RD, Dahlgren LA, Guelcher SA, Goldstein AS. Effect of fiber diameter and alignment of electrospun polyurethane meshes on mesenchymal progenitor cells. Tissue Engineering. 2009;15:2435.

3. Boland ED, Matthews JA, Pawlowski KJ, Simpson DG, Wnek GE, et al. Electrospinning collagen and elastin: Preliminary vascular tissue engineering. Frontiers in Bioscence. 2004;9:1422.

4. Bolgen N, Vargel I, Korkusuz P, Menceloglu YZ, Piskin E. In vivo performance of antibiotic embedded electrospun PCL membranes for prevention of abdominal adhesions. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2007;81:530.

5. Casper C, Stephens J, Tassi N, Chase DB, Rabolt JF. Controlling surface morphology of electrospun polystyrene fibers: Effect of humidity and molecular weight in the electrospinning process. Macromolecules. 2004;37:573.

6. Casper C, Yamaguchi N, Kiick KL, Rabolt JF. Functionalizing electrospun fibers with biologically relevant macromolecules. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:1998.

7. Chew SY, Mi R, Hoke A, Leong KW. The effect of the alignment of electrospun fibrous scaffolds on Schwann cell maturation. Biomaterials. 2008;29:653.

8. Doshi J, Reneker DH. Electrospinning process and application of electrospun fibers. Journal of Electrostatics. 1995;35:151.

9. Frisk S, Ikeda RM, Chase DB, Rabolt JF. Determination of the molecular orientation of poly(propyleneterephthalate) fibers using polarized raman spectroscopy: A comparison of methods. Applied Spectroscopy. 2004;58:279.

10. Gemmell CH, et al. Platelet activation in whole blood by artificial surfaces: Identification of platelet-derived microparticles and activated platelet binding to leukocytes as material-induced activation events. J.Lab and Clinic Med. 1995;125:276–287.

11. Greiner A, Wendorff JH. Electrospinning: A fascinating method for the preparation of ultrathin fibers. Angewandte Chemie (International edn.). 2007;46:5670.

12. Gururajan GS, Beebe SP, Chase TP, Rabolt DB. Continuous electrospinning of Nylon 6 nanofibers using an atomic force microscopy probe tip. Nanoscale. 2011;3:3300–3308.

13. Heydarkhan-Hagvall S, Schenke-Layland K, Dhanasopon AP, Rofail F, Smith H, et al. Three-dimensional electrospun ECM-based hybrid scaffolds for cardiovascular tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2907.

14. Inanc B, Arslan YE, Seker S, Elcin AE, Elcin YM. Periodontal ligament cellular structures engineered with electrospun poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) nanofibrous membrane scaffolds. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2009;90:186.

15. Inoguchi H, Tanaka T, Maehara Y, Matsuda T. The effect of gradually graded shear stress on the morphological integrity of a huvec-seeded compliant small-diameter vascular graft. Biomaterials. 2007;28:486.

16. Kakade MV, Givens S, Gardner K, Lee K-Y, Chase DB, et al. Electric field induced orientation of polymer chains in macroscopically aligned electrospun polymer nanofibers. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;10:2777.

17. Kim K, Luu YK, Chang C, Fang D, Hsiao BS, et al. Incorporation and controlled release of a hydrophilic antibiotic using poly(lactide-co-glycolide)-based electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds. Journal of Control Release. 2004;98:47.

18. Kim TG, Lee DS, Park TG. Controlled protein release from electrospun biodegradable fiber mesh composed of poly(epsilon-caprolactone) and poly(ethylene oxide). International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2007;338:276.

19. Lee CH, Shin HJ, Cho IH, Kang YM, Kim IA, et al. Nanofiber alignment and direction of mechanical strain affect the ECM production of human ACL fibroblast. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1261.

20. Lee K-H, Kim K-W, Pesapane A, Kim H-Y, Rabolt JF. Polarized FT-IR study of macroscopically oriented electrospun Nylon 6 nanofibers. Macromolecules. 2008;41:1494.

21. Liu X, Smith LA, Hu J, Ma PX. Biomimetic nanofibrous gelatin/apatite composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2252.

22. Lu L, Mikos AG. The importance of new processing in tissue engineering. MRS Bulletin. 1996;31:28.

23. Matthews JA, Wnek GE, Simpson DG, Bowlin GL. Electrospinning of collagen nanofibers. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:232.

24. Megelski S, Stephens JS, Chase DB, Rabolt JF. Arrays of micro- and nanopores on electrospun polymer fibers. Macromolecules. 2002;35:8456.

25. Nie H, Wang CH. Fabrication and characterization of PLGA/HAp composite scaffolds for delivery of BMP-2 plasmid DNA. Journal of Control Release. 2007;120:111.

26. Ouyang HW, Goh JC, Thambyah A, Teoh SH, Lee EH. Knitted poly-lactide-co-glycolide scaffold loaded with bone marrow stromal cells in repair and regeneration of rabbit Achilles tendon. Tissue Engineering. 2003;9:431.

27. Prabhakaran MP, Venugopal JR, Ramakrishna S. Mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to neuronal cells on electrospun nanofibrous substrates for nerve tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4996.

28. Riboldi SA, Sampaolesi M, Neuenschwander P, Cossu G, Mantero S. Electrospun degradable polyesterurethane membranes: Potential scaffolds for skeletal muscle tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4606.

29. Rockwood DN, Akins Jr RE, Parrag IC, Woodhouse KA, Rabolt JF. Culture on electrospun polyurethane scaffolds decreases atrial natriuretic peptide expression by cardiomyocytes in vitro. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4783.

30. Shields KJ, Beckman MJ, Bowlin GL, Wayne JS. Mechanical properties and cellular proliferation of electrospun collagen type II. Tissue Engineering. 2004;10:1510.

31. Stephens J, Rabolt JF, Fahnestock S, Chase D. From the spider to the web: Biomimetic processing of protein polymers and collagen. MRS Proceedings. 2003;774:31.

32. Xie J, Wang CH. Electrospun micro- and nanofibers for sustained delivery of paclitaxel to treat C6 glioma in vitro. Pharmaceutical Research. 2006;23:1817.

33. Xu CY, Inai R, Kotaki M, Ramakrishna S. Aligned biodegradable nanofibrous structure: A potential scaffold for blood vessel engineering. Biomaterials. 2004;25:877.

34. Yang F, Murugan R, Wang S, Ramakrishna S. Electrospinning of nano/micro scale poly(L-lactic acid) aligned fibers and their potential in neural tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2603.

35. Zong X, Bien H, Chung C-Y, Yin L, Fang D, et al. Electrospun fine-textured scaffolds for heart tissue constructs. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5330.