Chapter II.1.3

Cells and Surfaces in vitro

Introduction

There is no doubt that in vitro methods have been and will continue to be of great value to the progression of medical science. The culture of mammalian cells and the study of their behavior in vitro has led to new understandings of cell physiology (Neher and Sakmann, 1976), molecular biology (Mello, 2007), and many disease processes (Schwarz et al., 1985). In many experimental settings, the ability to extract and grow cells from host tissues is a powerful tool since experimental question(s) can be evaluated under standardized conditions without the many complicating influences from the host physiology.

As science has progressed, new in vitro techniques have developed beyond the culture of cells in glass or plastic dishes. Cell–substrate interactions are of particular interest since cells interact physically with the extracellular matrix (ECM) and often modify it in response to various stimuli. As a result, efforts to examine and recapitulate the in vivo environment in vitro often require modification of the cell culture substrates. Cell–substrate interactions at the micro- and nanoscales have been facilitated by new techniques, applications, and approaches that have emerged from the combination of engineering and biology. In practice, the chemistry, topography, and elasticity of the culture surface may be altered, and mechanical forces can also be applied to cells by physical deformation of the culture substrate.

With respect to tissue engineering and organ regeneration, advances in our understanding of cell–substrate interactions are essential to controlling cell behavior. For example, the ability to pattern cells with micron scale precision on a variety of substrates presents new opportunities to study and recreate cell–cell interactions required to generate functional tissues in vitro for subsequent implantation in vivo. This is of primary importance, since organs contain multiple cell types that are precisely arranged in close proximity to form complex structures.

This chapter provides a basic understanding of in vitro principles, beginning with a fundamental overview of the culture of cells and their interactions with surfaces. We then describe a number of techniques employed to manipulate the in vitro environment at the micro- and nanoscale and then discuss how these fundamental techniques can be applied to investigate and influence cell behavior.

A Basic Overview of Cell Culture

Tissue culture is a general term for the harvest of cells, tissues or organs, and their subsequent growth or maintenance in an artificial environment. Mammalian cells cultured in vitro have the same basic requirements as cells growing within an organism. Specialized approaches have been developed to replace a number of mammalian systems essential for life. In vitro, blood is replaced by the culture media, which bathes the cells and provides an energy source (glucose), essential nutrients (salts and amino acids), proteins and hormones (from added serum), and a buffer (to maintain pH balance). During culture, the byproducts of cellular metabolism are released into the media as its constituents are depleted. Since the culture media is not continually circulated and purified, it must be changed regularly to maintain optimal conditions for cell function. Not surprisingly, these culture conditions are also favorable for the growth of unwanted organisms such as fungi and bacteria. Since there is no immune system to control infection in vitro, anti-fungal and anti-bacterial agents can be added to the media on a prophylactic basis. To further reduce the likelihood of contamination by microorganisms, cells are manipulated under a laminar flow hood using strict aseptic (sterile) techniques. Laminar hoods control and direct filtered air to facilitate a sterile working environment by reducing the contact of air-borne bacteria and particulates with the culture dish and hood surfaces.

Cells in media are contained in culture dishes or flasks and incubated in a temperature-controlled (37°C) and humidified (95%) chamber. While the lids of the culture dishes cover and protect the media, they are not sealed and enable gas exchange within the incubator. The exchange of gas at the media surface acts like the lungs to maintain the gas balance necessary for metabolism. CO2 is usually added to the incubator at a low concentration (5%). The CO2 interacts with the bicarbonate buffer in the media to help maintain a pH of 7.0–7.4. Buffering counteracts pH changes in the media as it accumulates waste from cellular activity. Phenol red is commonly added as an indicator to monitor pH, and a change in the color of the media is often a sign of poor culture conditions. Since the culture dishes are not sealed they are prone to evaporation. To reduce evaporation, and prevent a subsequent change in media concentration, a water dish (with an anti-fungal/anti-bacterial agent) is usually placed in the bottom of the incubator to maintain a high level of ambient humidity.

Primary Culture

Cells for in vitro work may be obtained from tissue (primary culture) or from cell lines. Cells for primary culture are obtained by surgical dissection of living tissues. Cells can be obtained by passing media through the marrow cavities of the long bones, by collecting cells that grow out from a piece of tissue (explant culture) or by enzymatic digestion of tissue that contains cells. Enzymatic digestion of small pieces of tissue immersed in collagenase at 37°C breaks down the surrounding ECM and releases entrapped cells (enzymatic dissociation). After harvest, cells may be cultured in suspension or on culture substrates. Anchorage dependent cells are plated for a few days to remove dead or unwanted (non-adherent) cell types. Cells anchored to the surface of the culture plate are “released” by adding a mixture of trypsin, a protease found in the digestive system, and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Trypsin degrades proteins, including important cell adhesion proteins (CAPs) that anchor the cell to the culture surface. Over short treatment times, trypsin is generally not harmful to cells. EDTA is a chelating agent that binds calcium and magnesium ions. EDTA increases the effectiveness of trypsin and prevents cell aggregation after release from the culture dish.

Harvested cells are often filtered to produce a suspension of single cells. The single cell suspension is counted, and portions of the initial cell population are transferred to new culture dishes for expansion. Expansion is also referred to as sub-culturing or passaging the cells. Passaging cells ensures that cells are plated at a low density so they have space around them to proliferate. Under appropriate conditions, most cells proliferate and form a monolayer on the culture surface. The point at which cells completely cover the culture surface is referred to as confluence. At confluence, proliferation will generally cease because cell–cell contact results in contact inhibition. Unlike cell lines, primary cells are often used without passaging or passaged only a few times, since passaging can result in loss of cell characteristics (phenotype).

Cell Lines

Generating primary cultures by continually harvesting and isolating cells is a time-consuming task. As a result, it is often preferable to utilize cells that are obtained from stock maintained in the laboratory. Cell lines refer to cells that can be passaged many times without loss of their phenotype. Physiologically, these cells can divide repeatedly, without shortening of their telomeres (Hayflick, 1965). Cell lines differ from other cells in that they have escaped the Hayflick limit and are immortalized (Hayflick, 1985). Examples of a handful of commonly used cell lines, from a large number of existing cell lines, are presented in Table II.1.3.1.

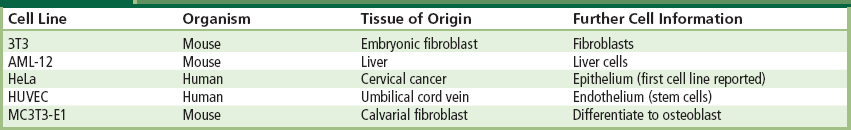

TABLE II.1.3.1 Examples of Some Commonly Used Cell Lines

Cell lines also offer an experimental advantage. In terms of strict experimental uniformity, primary cultures may contain unwanted cell types unintentionally included during harvest. Primary cultures may also contain slight genetic variations due to genetic differences arising from the harvest of cells from different animals. Since cell lines are derived from the same cell they are all genetic clones of the parent cell.∗ As a result, experiments using cell lines can be reproduced by different laboratories using the same cell, with obvious advantages for collaboration, verification, and reproducibility.

A large number of cell lines are derived from tumors or cells that have undergone spontaneous mutation or some form of manipulation. The HeLa cell line is an example that has been in use since the early 1950s and was derived from cervical cancer cells taken from Henrietta Lacks (Scherer et al., 1953). It is helpful to recognize that while cell lines may behave similarly to normal cells, they have been obtained by repeated culture and selection (Puck and Marcus, 1955; Browne and Al-Rubeai, 2007), by treating or transforming normal cells (using viruses, oncogenes, radiation, drugs or chemicals) (Prasad et al., 1994; Eiges et al., 2001; Groger et al., 2008), from transgenic mice (Connelly et al., 1989; Wu et al., 1994) or isolated from tumors (Riches et al., 2001; Yasuda et al., 2009). For example, transformed cells may present different morphologies and altered metabolisms (Priori et al., 1975; Wittelsberger et al., 1981), and often do not exhibit robust contact inhibition (Bell, 1977; Erickson, 1978). These behaviors strongly suggested that cell lines have the inherent potential to demonstrate responses that may not be typical of primary cells (Steele et al., 1991; Heckman, 2009). Therefore, when establishing new experimental protocols using cell lines it is recommended that the results of the protocol be validated with primary cells.

Cell lines can be obtained from nonprofit organizations such as the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), the European Collection of Cell Cultures (ECACC), and the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (CIMR). The ATCC (www.atcc.org), ECACC (www.hpacultures.org.uk), and the CIMR (www.coriell.org) provide high-quality cell lines which are subject to careful testing and validation. The testing process ensures that cells provided are free of unwanted organisms such as mycoplasma or that other unwanted cell types are not present. Cell lines obtained from tissue banks are usually meticulously characterized and preserved to maintain these materials in a manner that permits reproducibility of results across time and among laboratories around the world. In some cases, cell lines can be obtained from other research laboratories; however, caution should be exercised since the possibility exists that the cell lines may be contaminated with microorganisms or unwanted cell types.

Characteristics of Cultured Cells

Cultured cells often display characteristic behaviors and growth patterns. A well-known characteristic is contact inhibition. In 1954, Abercrombie and Heaysman proposed that cells do not form multilayers because they do not move over or under their neighbors (Abercrombie and Heaysman, 1954). Cells exhibiting contact inhibition will preferably migrate to unoccupied areas of the culture substrate, and will not use the upper surface of a confluent cell monolayer as substrate. Contact inhibition is closely related to the cessation of cell proliferation (Timpe et al., 1978), and is one reason why most cells cultured in vitro produce monolayers of cells (Garrod and Steinberg, 1973). When cultured cells are in complete contact with each other, plasma membrane ruffling and cell motility are inhibited, resulting in an overall cessation of cell growth (Heckman, 2009). For this reason, cells maintained in culture are frequently replated at lower densities so that growth and proliferation may continually occur.

Detecting Cancerous Cells In Vitro

The phenomenon of contact inhibition has diagnostic implications for assessing the malignancy of cells (Amitani and Nakata, 1977; Abercrombie, 1979). A predominant behavior of malignant cells is uncontrolled cell growth. The natural phenomenon of contact inhibition has been used as a test to distinguish cancerous from non-cancerous cells (Dehner, 1998). Interestingly, unlike normal cells, malignant cells will also proliferate in agar (a three-dimensional matrix) where no suitable binding sites for cell attachment exist (Whang-Peng et al., 1986).

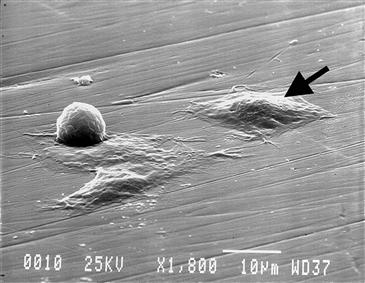

Cultured cells also often display characteristic shapes that can be used as visual cues to assess the health and differentiation of a culture population. For example, preosteoblastic cells are fibroblastic in shape, possessing a long “drawn out” morphology. Upon subsequent differentiation into mature osteoblasts, cells display a cuboidal appearance. Dead or non-adherent cells are often spherical in shape and float in the culture media.

Understanding Cell–Substrate Interactions

In vivo, cell–surface interactions are often explored as a means to enhance or control peri-implant tissue formation. Surface chemistry, topography, and elastic modulus (stiffness) of the substrate are all means to control and guide cell activity, and ultimately modulate tissue formation. This triad of properties is important for tissue engineering and organ regeneration where multiple cell types must be directed to form complex structures all in close proximity, and often with micron scale precision. In terms of three-dimensional scaffolds, tuning of scaffold chemistry, topography, and stiffness are all means to selectively guide cell development and differentiation within the bulk material.

Since most cells interact with a substrate (e.g., within the ECM) it is often desirable to control the interaction of cells with substrates in vitro. Modulation of the culture surface by fabrication of “engineered surfaces” comprised of micro- and nanosized chemical and topographical patterns or coatings have been used to investigate cell behavior such as adhesion, morphology, migration, proliferation, cell–cell communication, gene expression, production of ECM, differentiation, and responsiveness to extracellular signaling.

Surfaces for Cell Culture

It has long been established that most mammalian cells respond favorably to culture conditions that promote cell attachment. Cell attachment is often characterized by a change in cell morphology. Adherent cells possess a “flattened” appearance, often with an irregular cell shape and the extension of cellular processes (Figure II.1.3.1). Regular observation of cells in vitro is essential for successful culture as cell density, state, and contamination can all be readily assessed visually. In this regard, optically clear materials are practical as they permit simple assessment of cell growth and morphology during culture, and are well suited to many histological techniques that involve staining for quantification of cell activity. Glass, once a common form of culture ware, has been replaced by tissue culture polystyrene (TCP). While TCP is most widely used as a culture substrate, other polymers such as polyvinylchloride, polycarbonate, and polytetrafluoroethylene have been used. Advantages of TCP are that it is inexpensive, clear, easily formed and treated to modify surface groups, and unlike glass, it can be embedded and sectioned.

FIGURE II.1.3.1 Scanning electron microscopy image of MC3T3-E1 cells at various stages of adherence on polished titanium substrate demonstrating changes in cell morphology during attachment. Attached cells have a flattened morphology and form intimate contact with the substrate. Detached cells are round. SEM 1800X.

Process of Cell Attachment In Vitro

Cell attachment is the initial step in a cascade of cell–biomaterial interactions, and is important to cellular processes such as cell guidance, proliferation, and differentiation (Ruoslahti, 1996). For many adherent cells, cell proliferation can only occur on a substrate. As a result, cell–surface interactions are fundamental to understanding cell behavior, and provide an important means to control and quantify cell activity.

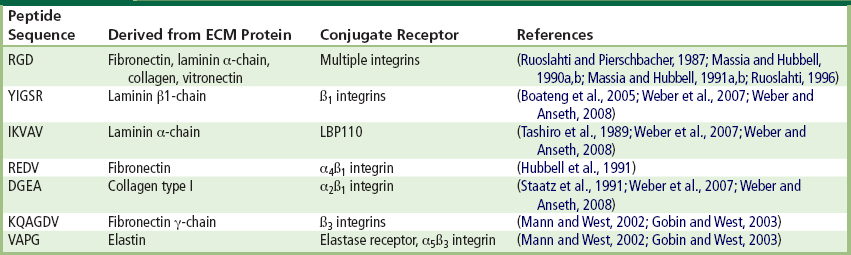

The process of cell attachment is largely understood (Ruoslahti and Pierschbacher, 1987; Ruoslahti and Reed, 1994; Ruoslahti, 1996; Garcia, 2005). In vitro, when hydrophilic surfaces like TCP are exposed to culture media containing serum, they are rapidly coated by a thin (~20 nm) layer comprised mainly of proteins (Andrade and Hlady, 1987; Kasemo and Lausmaa, 1994; Nakamura et al., 2007) that adsorb to the culture surface in a monolayer. The process of cell attachment to TCP (and many other materials) is indirect, since cells do not bind directly to TCP but instead bind to the adsorbed protein monolayer (Fredriksson et al., 1998). Cells make contact with, and anchor to, the adsorbed proteins at discrete peptide regions referred to as focal contacts (Gallant and Garcia, 2007). Cells possess heterodimeric transmembrane proteins composed of α and β subunits called integrins. Integrins are receptors that recognize and bind to specific anchoring proteins present on the conditioned TCP surface (Peter and Ma, 2006). The adsorbed proteins present short but specific peptide sequences (Table II.1.3.2) that are recognized by integrins as binding sites. Integrins recognize and bind to specific ligands such as fibronectin, vitronectin, collagen, and laminin. Over 18 α and 8 β receptor subunits have been identified, and these subunits combine to produce a wide variety of receptor types (Hynes, 2002). Of these combinations, the αvβ3 integrin is one of the most abundant and binds to vitronectin, fibronectin, von Willebrand factor, osteopontin, tenascin, bone sialoprotein, and thrombospondin (Hynes, 2002). A common peptide receptor for αvβ3 integrin is the RGD (arginine–glycine–aspartic acid) sequence (Ruoslahti and Pierschbacher, 1987). For the majority of cells cultured in vitro, fibronectin and vitronectin are important for cell attachment to TCP (Massia and Hubbell, 1991a; Steele et al., 1993).

TABLE II.1.3.2 Specific Peptide Sequences on Cell Anchoring Proteins

In their capacity as adhesion receptors, integrins play an important role in controlling various steps in the signaling pathways that regulate processes as diverse as cytoskeletal organization, cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and migration. In most cell types certain biochemical signals necessary for cell growth, function, and survival are triggered by integrins upon attachment. Without attachment, the cell eventually undergoes apoptosis, which is also known as programmed cell death (Ruoslahti and Reed, 1994).

Commercial and Experimental Modifications of Culture Surfaces

Polystyrene is a hydrophobic material that is not well suited to the attachment of most mammalian cells (Curtis et al., 1983). For the culture of non-adherent cells, untreated polystyrene dishes are routinely used. As previously described, most cells require modified surfaces that are suitable for protein adsorption before attachment can occur.

A variety of treatment methods have been employed to improve cell attachment and growth on the TCP surface (Table II.1.3.3). TCP treatments used to enhance cell adhesion are often proprietary and vendor specific, but some methods such as chemical treatment in sulfuric acid (Curtis et al., 1983), chemisorption (Shen and Horbett, 2001; Bain and Hoffman, 2003a), ionizing radiation (Callen et al., 1993) or exposure to plasma-based ionizing processes such as glow discharge (Amstein and Hartman, 1975; Koller et al., 1998) have been described in the literature. It is generally understood that these treatments impart a charge to the TCP surface that enhances its ability to interact with and bind specific CAPs present in the serum added to the culture media (Jacobson and Ryan, 1982; Lee et al., 1997).

TABLE II.1.3.3 Treatment Methods Employed to Improve Cell Attachment and Growth on the TCP Surface

| Approach | Technique | References |

| Surface modification | Corona discharge, Glow discharge | (Amstein and Hartman, 1975; Ertel et al., 1990; Chinn et al., 1994; Lee et al., 1994; Lee et al., 2003) |

| Oxidation | (Curtis et al., 1983; Chang and Sretavan, 2008; Frimat et al., 2009) | |

| Plasma etching | (Claase et al., 2003; Rhee et al., 2005) | |

| Surface chemical reaction | (Maroudas, 1977; Curtis et al., 1983; Kowalczynska and Kaminski, 1991) | |

| Ultraviolet irradiation | (Nakayama et al., 1993; Matsuda and Chung, 1994; Welle et al., 2002) | |

| Radiation grafting (thermo-sensitive polymers) | (Yamato et al., 2001; Yamato et al., 2002) |

It is important to recognize that the preparation of culture surfaces can have profound effects on the behavior of cultured cells (Shen and Horbett, 2001; Bain and Hoffman, 2003b). For some cell types, commercially available surfaces may be far from optimal, and identification of optimized substrates can be a laborious task, especially for cells that are difficult to culture in vitro. One approach has been the generation of culture surfaces comprised of mixtures of protein-adhesive and “protein-repellant” molecules or groups. Bain and Hoffman used a combination of protein adhesive diamine groups (N2) and hydrophobic trifluoropropyl groups (F3) to generate a large number of culture surfaces by varying the ratio of monomers in a silanization bath (Bain and Hoffman, 2003a). The different surfaces produced possessed varying affinities for protein adhesion and, as a result, cell adhesion. A surprising finding of the work was that the growth and activity of insulin-secreting cells was best supported by the most hydrophobic (F3) surfaces in the study (Bain and Hoffman, 2003b).

More direct approaches to tune substrate chemistry can be achieved by anchoring specific adhesion molecules to the culture substrate. In such investigations, it is often advantageous to retain only the molecule(s) of interest, while reducing or excluding non-specific protein adhesion as might occur with cells grown in normal, serum-enriched media (Koepsel and Murphy, 2009). Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) are a versatile and valuable tool that has been used to study protein adhesion (Prime and Whitesides, 1991; Li et al., 2007). SAMs are comprised of long alkane thiols anchored at the thiol end to the gold-coated substrate, while the other end is derivatized with small functional groups such as cell adhesion peptides or “protein-repellant” oligo(ethylene oxide) sequences. The functional groups can also be conjugated to specific proteins, such as monoclonal antibodies, or can interact with proteins in the media. SAMs can be tailored to exhibit specific amounts of protein adsorption, by controlling the composition of the monolayer (mixture of functional groups).

The control of ligand density and type provides another means to modify substrate chemistry and cell behavior. Gradients of immobilized ECM components and growth factors have also been shown to direct cell migration and shape (Liu et al., 2007; Inoue et al., 2009). Such experimental aspects can also be explored efficiently with microfluidic systems where the facile and reproducible generation of gradients utilizing small reagent volumes has been applied to the study of cell behavior in vitro (Du et al., 2009).

Dynamic Control of Cell Culture Surfaces

Controllable surfaces for cell culture have been generated that enable a predictable change in the adhesive or morphological characteristics of the surface. Changes in surface characteristics may be achieved by mechanical or physico-chemical methods, and the latter methods are the focus of this section. A wide variety of dynamic surfaces have been fabricated from SAMs with specific functional groups that are responsive to thermal, chemical, electrical or electromagentic (UV or visible light) stimuli. Dynamic culture surfaces can be used as a means to control cell adhesion. More sophisticated applications have been used to selectively pattern surfaces to generate a culture environment with multiple cell types specifically arranged in groups in close proximity to each other.

Dynamic culture surfaces have also been used to detach cells from substrates. Cell sheets have been spontaneously detached by cooling a thermally-sensitive, radiation- or plasma-polymerized poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (poly[NIPAAm]) polymer (Cheng et al., 2004). Okano’s group in Japan has pioneered in this method, using electron beam radiation grafting of NIPAAm monomer on the surfaces of cell culture dishes. (Yamato et al., 2001, 2002) (see Table II.1.3.3). At temperatures suitable for cell culture (above 32°C) the poly[NIPAAm] surface is hydrophobic and readily adsorbs cell adhesive proteins (CAPs), leading to the growth of a cell monolayer to confluence. However, when the temperature is reduced below a critical temperature (32°C) the poly[NIPAAm] surface becomes hydrophilic, and the cell sheet detaches as a contiguous, confluent monolayer, carrying with it the CAP monolayer. Such dynamic thermal control of cell adhesion can be particularly useful for the intact removal of a sheet of cells by avoiding the use of proteolytic enzymes such as trypsin that can disrupt natural cell–cell networks and compromise cellular integrity. Cell sheets have a variety of applications in tissue engineering (Elloumi-Hannachi et al., 2010; Gauvin et al., 2010), and the Okano group has applied them clinically as monolayers of corneal cells for repairing damaged or diseased eye surfaces.

Methods that switch surfaces from cell-adhesive to non-adhesive have also been reported using photo-responsive SAMs. These approaches generally modify the presentation of CAPs making them less accessible to the cell. Upon exposure to UV light, surfaces based on a combination of azobenzene groups and RGD ligands will “hide” the RGD groups by UV-induced conversion of the azobenzene functional group from polar to non-polar character (Auernheimer et al., 2005). Exposure to UV light reduced the exposed length of the azobenzene-RGD segments, and reduced cell adhesiveness by 17%. Nitro-spiropyran and methyl methacrylate polymer coatings have also been employed as photo-responsive surfaces (Higuchi et al., 2004). Nitro-spiropyran is a photo-responsive polymer that switches from a cell adhesive state to a non-adhesive (hydrophilic) state upon exposure to UV light.

Investigating Cell–Substrate Interactions

The cellular microenvironment consists of a myriad of signals arising from surrounding cells, the ECM, and soluble molecules. The ability to control and modulate cell behavior, through the cell environment, is important for understanding cell behavior as well as controlling a wide range of biomaterial interactions. In general, cell behavior can be modified by controlling substrate chemistry, topography, and elasticity, and investigations have traditionally focused on broad changes to the cell culture surface, such as those obtained by application of a coating. However, cell–cell and cell–ECM interactions in nature usually occur over very small, nanoscale distances.

New insights into cell behavior and physiology have been gained by utilizing and extending a variety of techniques and materials that can be used to influence the cell environment at the microscale. The following sections examine some of the fundamental concepts learned from examining cell behavior in response to substrate chemistry, topography, elasticity, and strain, alone and in combination at macro-, micro-, and nanoscales.

Limitations of Biomaterial Evaluation In Vitro

It is important to recognize that the in vitro evaluation of biomaterials is subject to specific constraints arising from the reduced complexity of the in vitro environment. First and foremost, there is no immune or inflammatory response in vitro. Nor is there the same cascade of events resulting from implantation, e.g., the interaction with components of blood, formation of a clot, vascularization, and recruitment of a variety of cells that participate in the wound healing response.

Cell Response to Substrate Chemistry

Surface chemistry is perhaps the most obvious, and in some cases, the most accessible parameter to control when modifying in vitro conditions to assess their effects on cell behavior. At the macroscale, a variety of strategies can be employed to modify culture surface chemistry. Most coating strategies aim to increase cell adhesion or to preferentially select for certain cell types. Uniform coatings may be achieved by either spin coating a solution of it on the substrate surface, or by immersion of the substrate in a solution of it, followed by draining and drying. Substrates have been coated in these ways with a variety of organic and inorganic compounds, such as collagen (Chlapowski et al., 1983; Kataropoulou et al., 2005), fibronectin (Klein-Soyer et al., 1989), gelatin (Aframian et al., 2000), and poly-L-lysine (Jensen and Koren, 1979). Culture surfaces have also been broadly coated with specific adhesion-related peptides. The peptide sequence arginine–glycine–aspartate (RGD) has been immobilized on a number of materials as a means of enhancing two-dimensional cell attachment (Massia and Hubbell, 1990a, 1991b; Cutler and Garcia, 2003; Petrie et al., 2008). Studies suggest that 1 pmol/mm2 of RGD may be required as a minimal surface density (Chollet et al., 2009), and that an increase in RGD density is generally beneficial to cell attachment (Massia and Hubbell, 1991b). However, it is worth noting that there may be an optimum ligand density for maximum cell attachment. The spatial organization of various cell ligands may also be achieved on some surfaces. This approach has been used to enhance the initial number of attached cells, to increase their proliferation or to preferentially select for specific cell types (Zemljic Jokhadar et al., 2007).

There are, however, instances where substrate coatings are of limited benefit, and examples of such include cultures where the applied coating may rapidly degrade or detach from the culture substrate. A common strategy to enhance cell adhesion is to modify the substrate chemistry to encourage the adsorption and presentation of certain CAPs or ligands (Keselowsky et al., 2003). Ligands are present on CAPs in the serum added to culture media. As previously discussed with TCP, a number of processes have been developed to enable modification of large culture surface areas to enhance CAP protein adsorption.

Micrometer-Scale Chemical Patterns

Patterning at the microscale is associated with the control of cell shape, position, and density, and presents a powerful tool to examine and control the cell microenvironment. A common approach is to generate a pattern of CAPs on a two-dimensional surface and then to plate with cells that adhere preferentially to the patterned, adhesive regions. Usually the non-adhesive regions are PEGylated. A multitude of patterns in various configurations have been attained using printing methods, as well as methods including dynamic surfaces as previously discussed.

Cells and proteins have been previously patterned on various substrates using SAMs (Mrksich and Whitesides, 1996), metal templates (O’Neill et al., 1990), stamped proteins, peptides (Hyun et al., 2001), and biopolymers (Bhatia et al., 1997), microfluidic channels (Takayama et al., 1999), membranes (Folch et al., 2000; Ostuni et al., 2000), polysaccharides (Khademhosseini et al., 2004; Suh et al., 2004), and cross-linked poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) (Khademhosseini et al., 2003). Non-contact methods can also be used to generate protein patterns and include films that are cross-linked by photolithography that selectively promote or exclude cell adhesion (Chien et al., 2009). In this manner, non-specific biological molecules can be used to create patterns of adhesive and/or non-adhesive regions. Short chains of PEG have been assembled on surfaces to form a brush-like layer that resists protein adsorption and, as a consequence, cell attachment.

Protein patterning has also been used to produce regions of preferential adhesion for specific cell types, to alter cell shape, to cluster cells together, to restrict their proliferation or to position different cell types in close proximity. Components of the ECM which participate in cell adhesion in vivo are candidates for studies involving chemical patterning in vitro. Fibronectin, laminin, vitronectin, and collagen are examples of ECM molecules commonly used for patterning cell adhesive regions. Such proteins may also be classified as CAPs.

Direct transfer of proteins or cells from a stamp to the substrate can also be used to generate micro- and nanoscale patterns. Microstamping or microcontact printing (μCP) is a technique whereby polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) molds are used to pattern substrates by the selective transfer of materials of interest (Mrksich and Whitesides, 1996). In one approach, the relief patterns on a PDMS stamp can be used to form patterns of SAMs on the surface of a substrate through conformal contact. Alkane thiols are used to pattern gold-coated surfaces by forming densely packed SAMs. The thiol end groups strongly interact with the gold surfaces, and the rest of the molecule can then be used to control surface chemistry, wetting, and protein and cell adhesion. For example, alkane thiols can be PEGylated at the opposite end from the –SH group to render gold-coated surfaces “non-fouling,” or protein and cell resistant. To micropattern surfaces using alkane thiols, a variety of methods have been employed such as μCP. In this approach, PDMS molds are “inked” with the alkanethiol solution, and transferred to the gold surface by conformal contact between the relief pattern and the substrate. Using μCP, micropatterns of SAMs terminated with PEG chains have been generated. These micropatterns have been used to immobilize proteins and cells on specific regions of a surface, and inhibit their contact with other regions by selectively modifying those regions with the non-fouling PEGs.

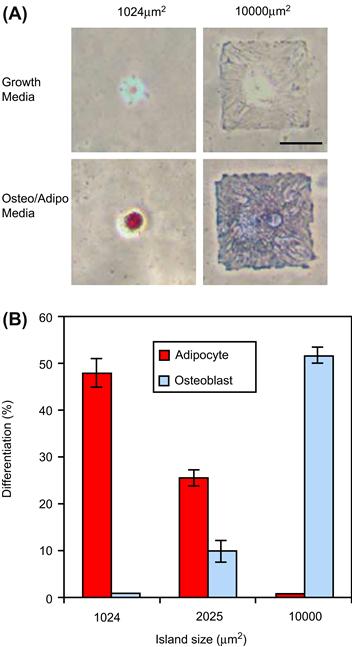

Using micropatterned fibronectin islands, Chen et al. reported that the area available for cell adhesion and the resultant cell shape governed whether individual cells grow or die, regardless of the type of matrix protein or antibody to integrin used to mediate adhesion (Chen et al., 1997, 1998) (Figure II.1.3.2). For bovine capillary cells, apoptosis significantly increased as fibronectin island size was reduced below 400 μm2. Using micropatterned fibronectin McBeath et al. demonstrated that cell shape regulated the differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) (McBeath et al., 2004); hMSCs that were permitted to adhere, spread, and flatten, differentiated into osteoblasts, while those that were not permitted to attach formed spherical shapes and resulted in adipocytes.

FIGURE II.1.3.2 Cell shape modulates hMSC differentiation: (A) Brightfield images of hMSCs plated onto small (1024 μm2) or large (10,000 μm2) fibronectin spots after 1 week. Fibronectin spots were patterned on a mixed SAM substrate by micro-contact printing. Large fibronectin spots supported osteogenesis (blue) while small fibronectin spots supported adipogenesis (red). Scale bar 50 μm. (B) Differentiation of hMSCs on 1024, 2025, or 10,000 μm2 islands after 1 week of culture. Small fibronectin spots resulted in adipogenesis, medium fibronectin spots supported both adipogenesis and osteogenesis, and large fibronectin spots resulted in osteogenesis.

(Reprinted from McBeath et al. (2004). Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment, Developmental Cell, 6(4), 483–495. Copyright (2004), with permission from Elsevier.)

Non-Fouling Surfaces in Cell Culture

As previously described, non-fouling surfaces may be created with PEGylated alkane thiols formed into SAMs. Other approaches include the generation and deposition of non-fouling coatings or films, such as plasma-deposited triglyme and tetraglyme films of the Ratner group (Johnston et al., 2005), plasma-deposited tetraglyme, and fluorocarbon-based films (Goessl et al., 2001; Cao et al., 2007).

PEG has been used in many chemical variations to generate non-fouling surfaces. Polymerization of PEG monomers to form brush-like non-fouling coatings has been investigated. Beginning with surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization, Lavanant et al. grew robust brush-like polymers of poly(ethylene glycol) methacrylate (PEGMA) on low density PE by photobromination followed by polymerization (Lavanant et al., 2010). Functionalization of the peptide brushes with the RGD containing peptide ligand, GGGRGDS, increased cell adhesion compared to the polymerized PEGMA surface, as expected.

Changes in the structure of the component molecules of SAMs can also reduce cell adhesion. For example, SAMs comprised of oligo(ethylene glycol) (OEG) with EG side chain lengths of 4, 9, and 23 were grafted to titanium as a non-fouling surface. Surfaces were exposed to 3T3 fibroblast cells in media with 10% FBS, and uncoated titanium was used as a control. At four hours, cells were visible on the Ti surface, but there was no cell adhesion and no visible difference between the SAMs with different side chain lengths. At 35 days, cell adhesion on surfaces was related to side chain length, and longer side chains resulted in fewer adhered cells. Eventually cells covered all the surfaces; however, complete cell coverage was observed at 7, 10, and 11 weeks for samples with side chain lengths of 4, 9, and 23 (Fan et al., 2006).

For many patterning applications, the ability to isolate or sequester cell adhesive regions by surrounding them with surfaces that resist cell attachment is of great interest. The practical applications include the fabrication of arrays of cells for high throughput testing, as well as patterned co-cultures for investigating complex interactions between different groups of homogenous cell populations. Microarrays of captured molecules surrounded by non-fouling backgrounds are one approach that has been used to identify and screen combinations of cell adhesion peptides to develop bioactive surfaces. Monchaux and Vermette grafted RGD and RGE (a non-adhesive control) as well as other known endothelial ligands (REDV and SVVYGLR) on a low-fouling carboxymethyl dextran background (Monchaux and Vermette, 2007). They concluded that RGD was necessary for cell adhesion, and that endothelial cells could discriminate against and would not adhere to RGE. Co-immobilization of the RGD peptide with VEGF or SVVYGLR significantly enhanced endothelial cell adhesion, while co-immobilization of RGD with either REDV or SVVYGLR induced a reduction in endothelial cell spreading.

The development of non-fouling surfaces from biodegradable or biologically relevant compounds is of great interest. Biodegradable ultra-low fouling peptide surfaces have been generated from natural amino acids that offer new and innovative means to control cell adhesion (Chen et al., 2009). Amino acids (H2N-CH-R-COOH) are molecules that possess an amine group (H2N), a carboxylic acid group (COOH), and an organic side chain (R) of varying length and composition. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins, and are the ubiquitous components of many organisms. Ultra-low fouling surfaces based on net neutral zwitterionic amino acids have been developed that can “catch and release” molecules of interest (Mi et al., 2010), potentially enabling a new generation of in vitro surfaces for diagnostic and assay-based testing.

Chemical Patterning for the Co-Culture of Cells

Cell–cell interactions are important for tissue development and function. During embryogenesis, the temporal and spatial signaling between cells of different origins is part of the cascade of events that support tissue growth and development (Yu et al., 2008). However, the process of harvesting tissue and isolating cells, as well as the purification of specific cell types, disrupts many of the cell–cell interactions found in vivo, resulting in a loss of cell–cell contact, signaling, structure, and general heterogeneity.

The co-culture of different cell types is one approach to enhance the in vitro environment and maintain cell phenotype in vitro (Nandkumar et al., 2002; Chang Liu and Chang, 2006). Co-cultures can be established by simply mixing two or more cell populations prior to plating; however, this provides little control over cell–cell contact, spacing or interaction. Greater control can be obtained through the use of patterned co-cultures which primarily control homotypic and heterotypic cell–cell contact. Using patterning techniques, co-cultures can be established where cell–cell contact, spacing, and interaction can be controlled with high resolution. Both cells and cell adhesive proteins may be patterned using selective adhesion to micropatterned substrates (Folch and Toner, 2000; Hui and Bhatia, 2007), by flow through a microfluidic channel (Chiu et al., 2000; Takayama et al., 2001), by stamping with a stencil-based approach (Chen et al., 1998; Folch and Toner, 2000) or by seeding on surfaces that dynamically switch from cell-adhesive to cell-repulsive (Edahiro et al., 2005; Kikuchi et al., 2009). A common requirement of most co-culture (and patterning) applications is the ability to selectively control and limit cell adhesion to specific areas of the substrate. As a result, non-fouling surfaces can be of considerable benefit.

A practical application of co-culturing is the study of cells from the liver (hepatocytes). Hepatocytes rapidly lose their ability to generate a characteristic protein (albumin) when cultured in vitro. Using mask-to-mask registration and photolithography, Hui and Bhatia (2007) generated surfaces with three distinct chemistries for the co-cultures of hepatocytes and 3T3-J2 fibroblasts. Hepatocytes preferentially adhered to collagen coated regions, and fibroblasts to serum coated glass regions (Figure II.1.3.3). A non-fouling PEG region was included that separated the two cell types and controlled the amount of contact or interaction between co-cultured populations for up to seven days (Figure II.1.3.3). At eight days, hepatocytes retained the ability to produce albumin.

FIGURE II.1.3.3 Examples of patterned co-cultures: (A) Glass coverslip with patterned photoresist. Scale bar is 2 mm. (B,C) Spatially restricted contact between hepatocytes and fibroblasts (day 6). (D) Phase contrast and fluorescence overlay showing expression of intracellular albumin in green after 8 days of culture, indicating retained hepatocyte function. (B–D) Scale bars are 200 μm. Control of cell organization via patterned surface chemistry: (E) 3T3-J2 fibroblasts excluded from islands of PEG-disilane (day 5). (F) Hepatocytes and 3T3-J2 fibroblasts patterned on a combination of collagen and PEG-disilane (day 2). (E,F) Scale bars 500 μm.

(Reprinted in part with permission from Hui and Bhatia. (April 2007). Langmuir, Vol 23(8), 4103–4107. Copyright 2007 American Chemical Society.)

High-Throughput Screening

Microarrays represent a specific type of chemical patterning. The arrays consist of a large number of small spots, each with a defined location and a unique chemical composition. This approach is suitable for testing biomaterials and microenvironments to enable the screening of large numbers of chemical combinations in a high-throughput manner. A high-throughput microarray that probes the cell–cell, cell–ECM, and cell–biomaterial interactions can be useful for studying cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation (Khademhosseini, 2005; Khademhosseini et al., 2006).

Typically, cell–ECM interactions are studied by using purified matrix proteins adsorbed to cell culture substrates. This approach requires large amounts of protein per 96- or 384-well plate, and can be prohibitively expensive. To address these challenges, new methods have been developed using pin tools (Cleveland and Koutz, 2005), piezo tips (Niles and Coassin, 2005), ultrasound (Strobl et al., 2004), and microarray (Flaim et al., 2005) technology for nanoliter liquid handling. Recently, robotic spotters capable of dispensing and immobilizing nanoliters of materials have been used to fabricate microarrays, where cell–matrix interactions can be tested and optimized in a high-throughput manner. For example, synthetic biomaterial arrays have been fabricated to test the interaction of stem cells with various extracellular signals (Anderson et al., 2004). Using this approach, thousands of polymeric materials were synthesized and their effect on the differentiation of human embryonicstem (ES) cells (Anderson et al., 2004) and human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC) (Anderson et al., 2005) were evaluated. These interactions have led to unexpected and novel cell–material interactions. Although the molecular mechanisms associated with the biological responses have yet to be clarified, such technology may be widely applicable in cell–microenvironment studies, and in the identification of cues that induce desired cell responses. Also, the materials which yield desired responses could be used as templates for tissue engineering scaffolds. Such an approach is a radical change from traditional methods of developing new biomaterials, where polymers have been individually developed and tested for their effect on cells. In addition to the screening of libraries of synthetic materials, the effect of natural ECM molecules on cell fate can be similarly evaluated in a high-throughput manner. In one example, combinatorial matrices of various natural ECM proteins were tested for their ability to maintain the function of differentiated hepatocytes, and to induce hepatic differentiation from murine ES cells (Flaim et al., 2005). A peptide and small molecule microarray made by a DNA microarray spotter was also used to study high-throughput cell adhesion (Falsey et al., 2001). A microarray of immobilized ligands was analyzed with three different biological assays such as protein-binding assay, functional phosphorylation assay, and cell adhesion assay. This array can be used to rapidly screen and analyze the functional properties of various ligands.

Nanometer-Scale Chemical Patterning

Nanosized chemical patterns generally do not direct cell shape or orientation as a result of their extremely small size relative to the cell. However, surfaces with chemical features on the nanoscale do modulate cell functions such as adhesion, proliferation, migration, differentiation, and gene expression.

Cell Response to Substrate Topography

All cells are exposed to some type of physical environment in vivo. Cell–cell interactions, the ECM, and biomaterials all present a surface to the cell that is quantifiable in terms of its surface features (Abrams et al., 2003; Liliensiek et al., 2009). As a field of study, surface topography defines the specific morphological characteristics of a surface. Surface topography may be generally described as isotropic (uniformity in all directions) or anisotropic (uniformity in one direction). Surface topography may be quantified by a number of techniques such as atomic force microscopy (AFM) or white light interferometery (WLI).

Unlike periodic surfaces typically fabricated for in vitro investigation (Clark et al., 1987; Chou et al., 1998; Brunette and Chehroudi, 1999), most biological surfaces present non-ordered features at the macro- and microscale which generally become more ordered at the nanoscale (Fratzl, 2008). Fibers in the ECM and pores in basement membranes are just a few examples of prevalent and quantifiable topographical features (Abrams et al., 2003; Liliensiek et al., 2009). Thus, it is not surprising that cells respond to topographical cues, and that surface topography of the culture surface presents another means to control and study cell behavior in vitro. Micro- and nanosized features are known to influence cell behavior, and both generally coexist in many biological surfaces. Accurate quantification of these surfaces is challenging, since most tools are optimized for quantifying micro- or nano-features individually, but not both at the same time (Guruprasad Sosale and Vengallatore, 2008).

In terms of cell activity, surface topography has been reported to affect proliferation, gene expression (Carinci et al., 2003), cell adhesion (Hamilton et al., 2006), motility (Clark et al., 1987), alignment (Clark et al., 1991), differentiation (Martinez et al., 2009), and matrix production (Hacking et al., 2008). In sensing and interacting with the topographical environment, evidence suggests that cells extend fine processes termed filopodia (Morris et al., 1985; Dalby et al., 2003a, 2004; Choi et al., 2007). While the specific mechanisms are poorly understood, changes in cell activity resulting from interaction with surface features have been linked to changes in cytoskeletal arrangement (Wojciak-Stothard et al., 1995) including actin filaments (Gerecht et al., 2007), nuclear shape (Dalby et al., 2003b), and ion channels (Tobasnick and Curtis, 2001). It is likely that these effects represent a small portion of the cellular events relating to interactions with surface topography, and different mechanisms or combinations of mechanisms may be activated by different feature sizes and shapes (Ball et al., 2007).

Micrometer-Scale Topography

Investigations concerning the response of cells to precisely patterned, microfabricated surfaces began decades ago. Fibroblasts (Brunette, 1986a), osteoblasts (Hamilton and Brunette, 2007), macrophages (Wojciak-Stothard et al., 1996), neutrophils (Tan and Saltzman, 2002), epithelial (Brunette, 1986b), endothelial (Bettinger et al., 2006), cardiomyocytes (Kim et al., 2005), and neuronal cells (Clark et al., 1991), have all demonstrated a reproducible response to surface texture on the microscale (Ireland et al., 1987; Britland et al., 1992; Curtis and Wilkinson, 1998; Fitton et al., 1998; Dalby et al., 2002b; Berry et al., 2004). Polarization or cell alignment along the direction of ridged surfaces is a phenomenon that is commonly observed when cells are cultured on linearly patterned substrates. Cell alignment to topographical features is referred to as contact guidance (Wood 1988; Wojciak-Stothard et al., 1996; Brunette and Chehroudi, 1999). With microscale- sized features, cell alignment generally increases with increasing groove depth and decreasing groove spacing (Bettinger et al., 2006); however, cell response to topography is highly dependent upon cell type (Figure II.1.3.4). For example, epithelial cells and fibroblasts are differently affected by surfaces with micron-sized grooves (Clark et al., 1987, 1990).

FIGURE II.1.3.4 Effect of micro and nano patterns on corneal epithelial cell alignment. (A) Cells were aligned perpendicularly to ridges that were 70 nm wide and 330 nm apart. (B) Expanded view of (A) showing filopodia also aligned perpendicularly to the patterns. (C) With increasing width and spacing (1900 nm ridge width, 2100 nm spacing), cells were aligned with the ridges; and (D) filopodia were guided by the topographic pattern.

(Reprinted from Teixeira et al. (2006). The effect of environmental factors on the response of human corneal epithelial cells to nanoscale substrate topography. Biomaterials, 27(21), 3945–3954. Copyright (2006), with permission from Elsevier.)

Nanometer-Scale Topography

It has been demonstrated that cells can sense and respond to features as small as 10–30 nm (Wojciak-Stothard et al., 1996; Dalby et al., 2002b). Compared to the microscale, where cells may be profoundly affected by a single feature, at the nanoscale a repetition of similar features has the greatest effect and provides the most predictable results regarding cell behavior (Curtis et al., 2004; Ball et al., 2007). Once again, cell response to topography is highly dependent upon cell type. Using surfaces of aligned ridges possessing a constant ridge spacing of 260 nm and depths varying from 100–400 nm, Clark demonstrated that neuronal cells were highly oriented in the ridge direction for all depths, epithelial-like cells were highly oriented for all depths, whereas the orientation of fibroblast-like cells increased with increasing depth from 50% orientation at 100 nm to nearly 95% orientation at 400 nm (Clark et al., 1991).

At the microscale, increasing the depth and decreasing the width of grooved or stepped surface features increases the probability of cell alignment with the topographical feature(s). At the nanoscale, it appears that a finite limit in feature sizes exists with respect to cell alignment to surface topography. By culturing fibroblasts on linearly patterned surfaces fabricated by e-beam lithography, it was determined that groove depths below 35 nm or ridge widths smaller than 100 nm did not result in cell alignment, and that 35 nm may be the threshold for whole cell fibroblast alignment (Loesberg et al., 2007). Similarly Teixeira et al. demonstrated a finite limit in the response of human corneal epithelial cells to surfaces with linearly patterned surfaces with groove spacing ranging from 400 to 4000 nm (groove width 330 to 2100 nm) (Teixeira et al., 2006). At groove spacings greater than 400 nm, cells were oriented in an increasingly parallel manner to the linear pattern (Figure II.1.3.4); however, at groove spacings less than 400 nm, cells were perpendicularly arranged. These findings further demonstrate a cell-specific sensitivity with regard to cell alignment to surface topography, and also imply that a limit exists in feature sizes that cells are able to recognize.

The effects of nano-topography on cell differentiation have also been reported. Proteomic-based studies have also shown that cells respond to nm-sized pits and pores in irregular patterns, leading to increased differentiation and matrix production by human osteoprogenitor cells (Kantawong et al., 2008). Likewise, studies with surfaces fabricated by the arrangement of titanium nanotubes have demonstrated that the nanotube diameter affects both hMSC differentiation and adhesion (Oh et al., 2009). Smaller diameter nanotubes (30 nm) increased adhesion, while larger diameters (100 nm) increased differentiation. Other authors using different cell lines and culture conditions have reported optimal nanotube diameters and spacing as low as 15 nm (Park et al., 2007). Topography at the nanoscale can also be used to effectively reduce cell adhesion. Kunzler et al. generated a constant gradient of nano-features (65 nm diameter and height) with the spacing as the only changing parameter along the gradient (Kunzler et al., 2007). This study demonstrated that the spacing or density of non-adhesive nanoscale features can disrupt cell adhesion, likely by restricting receptor–ligand interaction.

High-Throughput Screening of Surface Topography

Like microarrays used to test many chemical compounds at one time in a high-throughput manner, topographical arrays have been developed to assess the effects of systematic variances in surface topography. Lovmand et al. developed a topographical array consisting of 504 topographically distinct surface structures fabricated on silicon wafers that were coated with tantalum prior to cell seeding (Lovmand et al., 2009). Each structure consisted of a topographical pattern comprised of a series of circles, squares or rectangles that varied systematically in height from 0.6 to 2.4 μm, and feature size and spacing from 1.1 to 6.6 μm. Murine osteoblast cells (MC3T3-E1) were cultured on the array for up to 28 days to assess proliferation, cell area, and mineralization. It was determined that the height of the features had the greatest effect on mineralization, followed by feature size, then the gap size. The combined effects of feature size and gap size became important as feature height decreased.

Clinical Applications of Surface Morphology

Osteoblasts are substrate-dependent cells that have been widely used for investigating responses to surface topography. A considerable amount of work has been produced concerning the response of osteoblast cells to surface topography, and the end result of this work has been widely applied clinically to enhance the long-term fixation of dental and orthopedic implants by bone (Hacking et al., 1999, 2003). Mechanical fixation of an implant by the direct apposition of bone is referred to as osseointegration (Branemark et al., 1977; Albrektsson et al., 1981). Irregularly textured surfaces on titanium implants have been created by blasting the surface with small hard particles (Al2O3) that deform the relatively ductile titanium surface and produce a distinctly unordered micron-sized surface texture. It is common with dental implants that these surfaces are further processed by immersion in acid that superimposes a finer secondary nanosized structure upon the textured surface, and increases osseointegration.

A Note about Cell Lines in the Study of Surface Topography

To enhance optical clarity, the TCP surface is very smooth (Ra~1.2 nm) (Chang et al., 2007), and this has certain ramifications for the growth and development of cells in vitro. Adherent cell lines are selected preferentially for their ability to proliferate and differentiate on glass or tissue culture plastic. As a result, many cell lines have been selected based on their behavior on smooth, flat surfaces that are rarely found in vivo. Studies comparing the response of primary cells to cell lines derived from similar tissue sources have reported significant differences in cell activity (Fisher and Tickle, 1981; McCartney and Buck, 1981). This point becomes especially salient when working with surfaces where the effects of surface topography are the subject of primary interest (Clark et al., 1991; Hacking et al., 2008).

Cell Response to Substrate Elasticity

While surface chemistry and topography modulate cell function, it is increasingly evident that cells respond to the physical or mechanical properties (stiffness) of the substrate. Stiffness can be described as the resistance of a solid material to deformation, and is commonly defined by elastic modulus (E) and reported in units referred to as a “pascal” (Pa). Excluding bone (10–20 × 109 Pa), most tissues have an elastic moduli in the range of 101 to 106 Pa, substantially lower than the elastic moduli of most culture surfaces like TCP (3–3.5 × 109 Pa).

Hydrogels are well-suited to the study of cell substrate interactions since their stiffness can be varied by controlling the water content of the gel, which is controlled by modifying the polymer concentration or the relative extent of cross-linking. Hydrogels can also be made from a very diverse variety of natural and synthetic materials, such as hyaluronic acid (HA), fibrin, alginate, agarose, chitosan, polyacrylamide, and PEG. In terms of collagen hydrogels, gel stiffness may be increased by increasing the collagen concentration (Brigham et al., 2009) or reducing the thickness of the gel and immobilizing it on a glass substrate (Arora et al., 1999).

The stiffness of the substrate affects cell adhesion, spreading, and migration, especially the last two. In two-dimensional cultures, cells preferentially migrate towards surfaces of greater stiffness, a phenomenon referred to as mechanotaxis (Lo et al., 2000). In two-dimensional systems endothelial and fibroblast cells cultured on collagen-coated substrates that were classified as compliant (~5 × 103 Pa) or stiff (~70 × 103 Pa) demonstrated remarkably different behaviors (Opas, 1994). Cells cultured on compliant substrates had reduced spreading, increased lamellipodia activity, and greater migration. Cells cultured on stiffer substrates generally increased in proliferation; however, the specific effect seen is cell-type dependent (Pelham and Wang, 1997). There is substantial evidence that substrate stiffness also affects cell proliferation in two-dimensional as well as three-dimensional culture systems (Wong et al., 2003).

Substrate elasticity can also be used to direct the differentiation of certain cell types. MSCs cultured on collagen-coated substrates of varying stiffness can be directed toward neuronal, myogenic, and osteogenic lineages (Engler et al., 2006). For example, adult neural stem cells will selectively differentiate to neurons on softer substrates (1 × 102 − 5 × 102 Pa) or glial cell types on stiffer substrates (1 × 103 − 1 × 104 Pa) (Saha et al., 2008). These findings suggest that stem cells are able to recognize and differentiate according to physiologically relevant substrate stiffness.

Cell Response to Mechanical Deformation (Strain)

There has been considerable work assessing the response of cells to mechanical strain or deformation (Buckwalter and Cooper, 1987). Forces can be applied directly to adherent cells in vitro by either elongation or compression of their substrate (two-dimensional) or matrix (three-dimensional). With respect to cyclic tensile loads, in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional cultures, cells predominantly align in the direction of the applied load and assume an elongated morphology (Toyoda et al., 1998; Henshaw et al., 2006; Haghighipour et al., 2007).

Because of the loadbearing function and well-known adaptation to load of the musculoskeletal system, cells of this system have been evaluated on surfaces under conditions of tensile and compressive strain. Toyoda et al. cultured cells harvested from the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and synovium (Toyoda et al., 1998). Cells were subjected to cyclic tensile load for 24 hours on culture plates with flexible rubber bases. For both cell types, tensile load increased cell alignment and elongation; however, tensile load only increased the production of collagen type I in cells derived from the ACL (Toyoda et al., 1998). These results have been supported by similar studies where fibroblasts subjected to cyclic tensile strain increased the formation of organized ECM, increased collagen production, and increased metabolic activity compared to unloaded controls (Hannafin et al., 2006; Joshi and Webb, 2008).

Bone is another well-known loadbearing tissue, and the extent of mineralization and bone mineral density is load dependent (Rodionova and Oganov, 2003). In vitro, cyclic strain in both tensile (Hanson et al., 2009) and compressive (Goldstein, 2002) loading enhances osteoblast mineralization. Thus, strain appears to be an important stimulus for the generation of mineralized and tendon-like tissues in vitro. These findings have led to the fabrication of bioreactors that can apply physiologic loads to developing tissue to enhance the production and alignment of ECM in a number of tissues including cardiac (Kortsmit et al., 2009), bone (van Griensven et al., 2009), cartilage (Preiss-Bloom et al., 2009), and tendon (Riboh et al., 2008).

Comparison and Evaluation of Substrate Cues

As previously discussed, cells respond to a number of surface cues such as chemistry, topography, elasticity, and strain (sometimes cyclic strain). Evaluating cell response to multiple cues is inherently difficult, since substrate properties are often interrelated. In many in vitro investigations of biomaterials it may be difficult to clearly separate the effects of surface chemistry from those of morphology and elasticity. This is particularly problematic in cases where the unique properties of a material may arise from the manufacturing process (Bobyn et al., 1999; Hacking et al., 2002). In such investigations, it is important to recognize that subtle changes in biomaterial properties can have profound effects on cellular response, and ultimately in vivo function. This is especially true, for example, of implant coatings where responses to surface morphology need to be dissociated from other factors, such as surface chemistry. Experimental controls must not just approximate surface morphology, but must match it precisely, since subtle changes in surface morphology have the potential to confound experimental findings. In many cases, however, it may not be practical or even possible to produce an exact morphological control from a different biomaterial. A morphological control may be generated by coating the surface of interest with a thin-film that is dense, durable, homogenous, and does not alter the surface morphology. There are a variety of thin-film deposition techniques collectively referred to as physical vapor deposition (PVD) that have been employed by several research groups (Hacking et al., 2002, 2007; Meredith et al., 2007). While other coating methods exist, PVD is advantageous since samples can be processed at lower temperatures in a relatively inert environment.

Control of substrate elasticity can be achieved by varying the composition and curing conditions. PDMS, for example, can be prepared with a range of elasticity (2.8–1882 kPa) by varying the ratio of base to curing agent (Cheng et al., 2009). Since PDMS can be cast into many shapes, patterned surfaces with varying elasticity can be created. These surfaces can be subsequently coated to achieve uniform and comparable surface chemistry. Similarly, by progressively reducing the thickness of a gel to a thin film, chemical composition can be maintained while substrate elasticity changes.

While the contributions of topography, chemistry, elasticity, and strain to cell behavior have been evaluated and documented for a wide variety of cell types, much of the literature has evaluated the effects of only one stimulus in each experimental setting. In vivo, however, it is reasonable to expect that cells experience a wide range of stimuli simultaneously. Since physical cues such as chemistry, topography, elasticity, and strain can produce both synergistic and opposing effects on cell behavior, it is of interest to evaluate their simultaneous effect on cell behavior, and if possible describe a hierarchy of cellular cues. However, since the cellular response to physical stimuli is often dependent upon cell phenotype, and is further influenced by soluble factors, broad exploration of these phenomena presents a challenging combinatorial experimental environment.

Chemistry and Topography

Using a combination of patterning techniques including photolithography, Curtis established that fibroblasts respond to both chemical and topographic patterns (Curtis and Wilkinson, 1999). However, when both chemical and topographical stimuli were combined and orthogonally opposed on the same surface, cells aligned with nanosized topographical patterns. Curtis coined the term “topographic reaction” to describe these events (Curtis and Wilkinson, 1999). Similarly, a preference of cellular alignment on chemical patterns versus response to topographic cues in the presence of both topographic and chemical patterns has been demonstrated in a number of studies (Charest et al., 2006; Gomez et al., 2007).

Chemistry and Strain

Hyun et al. developed a system to evaluate the combined effects of chemical patterning and strain on cell alignment (Hyun et al., 2006). Thin paraffin films were patterned with adhesive regions of fibronectin to which NIH 3T3 fibroblasts adhered and aligned. After cells aligned in the direction of the chemical patterning, the paraffin films with the adherent cells were subjected to cyclical stretch. Mechanical force was applied perpendicular to the cell alignment resulting from chemical patterning, and the actin cytoskeleton realigned along the axis of applied mechanical stress. Stretched cells showed altered gene expression of cytoskeletal and matrix proteins in response to mechanical deformation.

Topography and Strain

Cheng et al. (2009) fabricated patterned PDMS substrates consisting of parallel microchannels (2 μm wide, 2 μm separation, and 10 μm deep) that were subjected to cyclic compressive strain applied perpendicular to the direction of the channels. After six hours of compression, fibroblasts cultured on the patterned PDMS substrate aligned in the direction of the microchannels (topographical cue) and perpendicular to the direction of compression. Elastic microgrooved surfaces have also been utilized to maintain the cellular orientation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) while subjected to cyclic tensile strain (Kurpinski et al., 2006).

Summary

In vivo, cells are responsive to a myriad of substrate-related signals within the environment. At the micro- and nanoscale, interactions with the ECM expose the cell to a variety of chemical moieties and topographical features. Micro- and nanoscale technologies have provided many new tools to manipulate the in vitro environment. Cell behavior may be modified by patterns of cell adhesive ligands and topographical features. Further modification of cell behavior can be achieved by altering substrate mechanical properties, such as elasticity, or by deformation of the cell shape. With respect to generating complex tissue structures, substrate cues like topography, chemistry, and matrix elasticity are promising candidates for controlling cell differentiation. Unlike soluble factors, substrate cues can provide specific information for directing and controlling cell behavior. The combination of multiple physical cues presents new and potentially useful methods to direct and control cell development and behavior.

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

ACL anterior cruciate ligament

ATCC American Type Culture Collection

CIMR Coriell Institute for Medical Research

EDTA ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

hMSCs human mesenchymal stem cells

REDV Arginine-Glutamic Acid-Aspastic Acid Valine

RGD arginin–glycine–aspartate, adhesion-related peptide sequence

RGE Arginine-Glycine-Glutamic Acid

SAMs self-assembled monolayers

SVVTGLR Serie-Valine-Valine-Tyrosine-Glycine-Leucine-Arginine

TCP tissue culture polystyrene

Bibliography

1. Abercrombie M. Contact inhibition and malignancy. Nature. 1979;281(5729):259–262.

2. Abercrombie M, Heaysman JE. Observations on the social behaviour of cells in tissue culture II Monolayering of fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1954;6(2):293–306.

3. Abrams GA, Murphy CJ, Wang ZY, Nealey PF, Bjorling DE. Ultrastructural basement membrane topography of the bladder epithelium. Urol Res. 2003;31(5):341–346.

4. Aframian DJ, Cukierman E, Nikolovski J, Mooney DJ, Yamada KM, et al. The growth and morphological behavior of salivary epithelial cells on matrix protein-coated biodegradable substrata. Tissue Eng. 2000;6(3):209–216.

5. Albrektsson T, Branemark PI, HanssonH A, Lindstrom J. Osseointegrated titanium implants Requirements for ensuring a long-lasting, direct bone-to-implant anchorage in man. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981;52(2):155–170.

6. Amitani K, Nakata Y. Characteristics of osteosarcoma cells in culture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977;122:315–324.

7. Amstein CF, Hartman PA. Adaptation of plastic surfaces for tissue culture by glow discharge. J Clin Microbiol. 1975;2(1):46–54.

8. Anderson DG, Levenberg S, Langer R. Nanoliter-scale synthesis of arrayed biomaterials and application to human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(7):863–866.

9. Anderson DG, Putnam D, Lavik EB, Mahmood TA, Langer R. Biomaterial microarrays: Rapid, microscale screening of polymer-cell interaction. Biomaterials. 2005;26(23):4892–4897.

10. Andrade JD, Hlady V. Plasma protein adsorption: The big twelve. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1987;516:158–172.

11. Arora PD, Narani N, McCulloch CA. The compliance of collagen gels regulates transforming growth factor-beta induction of alpha-smooth muscle actin in fibroblasts. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(3):871–882.

12. Auernheimer J, Dahmen C, Hersel U, Bausch A, Kessler H. Photoswitched cell adhesion on surfaces with RGD peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(46):16107–16110.

13. Bain JR, Hoffman AS. Tissue-culture surfaces with mixtures of aminated and fluorinated functional groups Part 1 Synthesis and characterization. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2003;14(4):325–339.

14. Bain JR, Hoffman AS. Tissue-culture surfaces with mixtures of aminated and fluorinated functional groups Part 2 Growth and function of transgenic rat insulinoma cells (betaG I/17). J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2003;14(4):341–367.

15. Ball MD, Prendergast U, O’Connell C, Sherlock R. Comparison of cell interactions with laser machined micron- and nanoscale features in polymer. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;82(2):130–134.

16. Bell Jr PB. Locomotory behavior, contact inhibition and pattern formation of 3T3 and polyoma virus-transformed 3T3 cells in culture. J Cell Biol. 1977;74(3):963–982.

17. Berry CC, Campbell G, Spadiccino A, Robertson M, Curtis AS. The influence of microscale topography on fibroblast attachment and motility. Biomaterials. 2004;25(26):5781–5788.

18. Bettinger CJ, Orrick B, Misra A, Langer R, Borenstein JT. Microfabrication of poly (glycerol-sebacate) for contact guidance applications. Biomaterials. 2006;27(12):2558–2565.

19. Bhatia SN, Yarmush ML, Toner M. Controlling cell interactions by micropatterning in co-cultures: Hepatocytes and 3T3 fibroblasts. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;34(2):189–199.

20. Bobyn JD, Stackpool GJ, Hacking SA, Tanzer M, Krygier JJ. Characteristics of bone ingrowth and interface mechanics of a new porous tantalum biomaterial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(5):907–914.

21. Branemark PI, Hansson BO, Adell R, Breine U, Lindstrom J, et al. Osseointegrated implants in the treatment of the edentulous jaw Experience from a 10-year period. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Suppl. 1977;16:1–132.

22. Brigham MD, Bick A, Lo E, Bendali A, Burdick JA, et al. Mechanically robust and bioadhesive collagen and photocrosslinkable hyaluronic acid semi-interpenetrating networks. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15(7):1645–1653.

23. Britland S, Clark P, Connolly P, Moores G. Micropatterned substratum adhesiveness: A model for morphogenetic cues controlling cell behavior. Exp Cell Res. 1992;198(1):124–129.

24. Browne SM, Al-Rubeai M. Selection methods for high-producing mammalian cell lines. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25(9):425–432.

25. Brunette DM. Fibroblasts on micromachined substrata orient hierarchically to grooves of different dimensions. Exp Cell Res. 1986;164(1):11–26.

26. Brunette DM. Spreading and orientation of epithelial cells on grooved substrata. Exp Cell Res. 1986;167(1):203–217.

27. Brunette DM, Chehroudi B. The effects of the surface topography of micromachined titanium substrata on cell behavior in vitro and in vivo. J Biomech Eng. 1999;121(1):49–57.

28. Buckwalter JA, Cooper RR. Bone structure and function. Instr Course Lect. 1987;36:27–48.

29. Callen BW, Sodhi RN, Shelton RM, Davies JE. Behavior of primary bone cells on characterized polystyrene surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27(7):851–859.

30. Cao L, Chang M, Lee CY, Castner DG, Sukavaneshvar S, et al. Plasma-deposited tetraglyme surfaces greatly reduce total blood protein adsorption, contact activation, platelet adhesion, platelet procoagulant activity, and in vitro thrombus deposition. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81(4):827–837.

31. Carinci F, Pezzetti F, Volinia S, Francioso F, Arcelli D, et al. Analysis of osteoblast-like MG63 cells’ response to a rough implant surface by means of DNA microarray. J Oral Implantol. 2003;29(5):215–220.

32. Chang TY, Yadav VG, De Leo S, Mohedas R, Rajalingam B, et al. Cell and protein compatibility of parylene-C surfaces. Langmuir. 2007;23(23):11718–11725.

33. Chang Liu Z, Chang TM. Coencapsulation of hepatocytes and bone marrow cells: In vitro and in vivo studies. Biotechnol Annu Rev. 2006;12:137–151.

34. Charest JL, Eliason MT, Garcia AJ, King WP. Combined microscale mechanical topography and chemical patterns on polymer cell culture substrates. Biomaterials. 2006;27(11):2487–2494.

35. Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Geometric control of cell life and death. Science. 1997;276(5317):1425–1428.

36. Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Micropatterned surfaces for control of cell shape, position, and function. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;14(3):356–363.

37. Chen S, Cao Z, Jiang S. Ultra-low fouling peptide surfaces derived from natural amino acids. Biomaterials. 2009;30(29):5892–5896.

38. Cheng CM, Steward Jr RL, LeDuc PR. Probing cell structure by controlling the mechanical environment with cell-substrate interactions. J Biomech. 2009;42(2):187–192.

39. Cheng X, Wang Y, Hanein Y, Bohringer JF, Ratner BD. Novel cell patterning using microheater-controlled thermoresponsive plasma films. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;70(2):159–168.

40. Chien HW, Chang TY, Tsai WB. Spatial control of cellular adhesion using photo-crosslinked micropatterned polyelectrolyte multilayer films. Biomaterials. 2009;30(12):2209–2218.

41. Chiu DT, Jeon NL, Huang S, Kane RS, Wargo CJ, et al. Patterned deposition of cells and proteins onto surfaces by using three-dimensional microfluidic systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2000;97(6):2408–2413.

42. Chlapowski FJ, Minsky BD, Jacobs JB, Cohen SM. Effect of a collagen substrate on the growth and development of normal and tumorigenic rat urothelial cells. J Urol. 1983;130(6):1211–1216.

43. Choi CH, Hagvall SH, Wu BM, Dunn JC, Beygui RE, et al. Cell interaction with three-dimensional sharp-tip nanotopography. Biomaterials. 2007;28(9):1672–1679.

44. Chollet C, Chanseau C, Remy M, Guignandon A, Bareille R, et al. The effect of RGD density on osteoblast and endothelial cell behavior on RGD-grafted polyethylene terephthalate surfaces. Biomaterials. 2009;30(5):711–720.

45. Chou L, Firth JD, Uitto VD, Brunette DM. Effects of titanium substratum and grooved surface topography on metalloproteinase-2 expression in human fibroblasts. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;39(3):437–445.

46. Clark P, Connolly P, Curtis AS, Dow JA, Wilkinson CD. Topographical control of cell behaviour I Simple step cues. Development. 1987;99(3):439–448.

47. Clark P, Connolly P, Curtis AS, Dow JA, Wilkinson CD. Topographical control of cell behaviour: II Multiple grooved substrata. Development. 1990;108(4):635–644.

48. Clark P, Connolly P, Curtis AS, Dow JA, Wilkinson CD. Cell guidance by ultrafine topography. In vitro J Cell Sci. 1991;99(Pt 1):73–77.

49. Cleveland PH, Koutz PJ. Nanoliter dispensing for uHTS using pin tools. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2005;3(2):213–225.

50. Connelly CS, Fahl WE, Iannaccone PM. The role of transgenic animals in the analysis of various biological aspects of normal and pathologic states. Exp Cell Res. 1989;183(2):257–276.

51. Curtis AS, Wilkinson CD. Reactions of cells to topography. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 1998;9(12):1313–1329.

52. Curtis A, Wilkinson C. New depths in cell behaviour: Reactions of cells to nanotopography. Biochem Soc Symp. 1999;65:15–26.

53. Curtis AS, Forrester JV, McInnes C, Lawrie F. Adhesion of cells to polystyrene surfaces. J Cell Biol. 1983;97(5 Pt 1):1500–1506.