Chapter II.1.6

Effects of Mechanical Forces on Cells and Tissues (The Liquid–Cell Interface)

Mechanical properties of materials have already been covered in Chapter I.1.3 on “Bulk Properties of Materials.” In this chapter, we will cover the effects of mechanical forces on cells within tissues, on the surfaces of biomaterials or within polymer scaffolds, focusing primarily on the effects of fluid forces. Because host cells interact with implanted materials or because cells are implanted as therapeutic entities in themselves, often within a biomaterial scaffold, the response of cells to mechanical forces is important to consider in order to predict the success of an implant. Cells that are particularly adapted for functioning in concert with physical forces are those of the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems, but all cells experience some mechanical forces. In fact, the appropriate local mechanical environment appears to be crucial for maintenance of proper cell phenotype. This chapter will focus on physiological and pathological flow-induced shear stress and fluid-induced strains that cells experience with emphasis on the effects of these forces on cell function. The key role of mechanical forces in tissue formation and maintenance of cell–extracellular matrix and cell–cell interactions will be discussed in Chapter II.6.5 in the context of micromechanical design criteria for tissue-engineered biomaterials.

Cellular Detection of Mechanical Forces

Mechanotransduction is the transduction of mechanical forces applied to a cell or tissue into chemical and biological responses. Sensors of mechanical forces include ion channels, G-protein-coupled receptors, intercellular junctions, and focal adhesions (Davies, 1995; Papadaki and Eskin, 1997). Most of these sensors have direct connections to the cytoskeleton, and often are unable to transduce physical forces when the attachment to the cytoskeleton is lost, suggesting that coupling of surface mechano-receptors to the cytoskeleton is required for mechanical transduction (Alenghat and Ingber, 2002). An additional indirect effect of mechanical force is in the redistribution of extracellular signaling molecules. Mechano-sensing cells, such as hair cells in the inner ear, are specialized for their role in sensing mechanical forces. However, most other cells with primary functions that do not include sensing mechanical forces are responsive to such forces if exposed to them.

Cells that are particularly adapted for functioning in concert with physical forces are those of the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems, but all cells experience some mechanical forces. In fact, the appropriate local mechanical environment appears to be crucial for maintenance of proper cell phenotype.

Mechano-sensing cells, such as hair cells in the inner ear, are specialized for their role in sensing mechanical forces. However, most other cells with primary functions that do not include sensing mechanical forces are responsive to such forces if exposed to them.

Blood Vessels

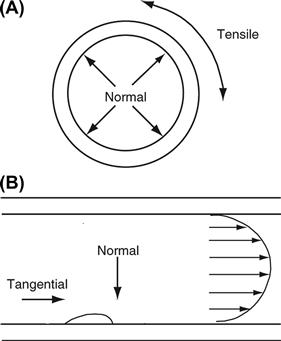

Mechanical forces resulting from blood flow directly affect cellular functions and morphology and thus, the physiology of the cardiovascular system (Davies, 2009). The forces to which cells of the blood vessels are subjected directly include wall shear stress and circumferential strain (Figure II.1.6.1). Disruption or distortion of these forces affects local cellular homeostasis, and may prime the area for development of pathology. Sites of atherosclerosis in humans have been shown to be non-random, and are strongly correlated with curved or branched sites in the vasculature that, as a result of their geometry, experience low time-averaged shear stress, shear stress reversal, and spatial and temporal gradients in shear stress (Glagov et al., 1988; Davies, 2008). Disturbances in mechanical forces due to implantation of medical devices can also alter cellular function. Small diameter arterial grafts (both synthetic and autologous vein) frequently fail because of compliance mismatch with the native vessel and resulting flow and wall strain disturbances at the anastomoses (see Box 1) (Singh et al., 2007)

FIGURE II.1.6.1 Schematic representation of the hemodynamic forces acting on the artery wall. (A) Cross-section through the artery, in which all layers are constantly subjected to tensile stress (cyclic strain) which arises from normal forces generated by the pusatility of blood flow. (B) Longitudinal section through the artery. Fluid flow profile (illustrated by the parabola) imparts tangential forces (shear stress) to the blood vessel wall. Endothelial cells lining the blood vessel wall respond first to this force.

Box 1 Hemodialysis Access Fistulas

Placement of (A) and (B) fistulas, and (C) grafts for access to the blood for hemodialysis. (PTFE, polytetrafluoroethylene)

(From: Singh et al. (2007). Successful angioaccess. Surg. Clin. North Am., 87, p. 1213. Elsevier.)

Blood vessels are comprised of three major cell types: endothelial cells; smooth muscle cells; and fibroblasts. A one-cell thick layer of endothelial cells forms the endothelium that lines the lumen of the entire vasculature. Large arteries also include a middle layer, the media, which consists of smooth muscle cells with secreted extracellular matrix, and an outermost layer, the adventitia, consisting primarily of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix, which also contains blood vessels and nerves supplying the artery itself.

Extensive studies that apply shear stress or cyclic strain to endothelial cells in vitro confirm that these cells actively participate in vascular physiology. Although only one cell thick, the endothelium provides a permeability barrier; controls thrombosis and hemostasis by maintaining an active thromboresistant surface, which no biomaterial has yet been able to match, and acts as a mechanosensor for the underlying tissue. Smooth muscle cells in the medial layer contract, relax, proliferate, synthesize matrix or migrate in response to shear stress, cyclic strain, and paracrine factors (biochemical signals) from endothelial cells. Vessels denuded of the endothelium expose the smooth muscle cells and matrix to blood flow, resulting in binding of platelets and, subsequently, thrombosis (Wagner and Frenette, 2008).

Effect of Shear Stress on Blood Vessels

The flow of blood over the endothelium generates viscous drag forces in the direction of flow. The resulting tangential force exerted per unit area of vessel surface at the blood–endothelium surface defines shear stress. Mathematically, the product between the viscosity (μ) and the velocity gradient at the wall, also known as the wall shear rate (γ), equates to wall shear stress (τw) (Equation 1):

(1)

(1)

With ventricular contraction, momentum propagates as waves down the aorta, but diminishes in amplitude on the arterial side of the circulation, with distance from the heart. Pulsatility is generated by the pumping action of the heart, and gives rise to pulsatile shear stress and cyclic strain. Typical mean arterial values of shear stress range from 6 to 40 dyn/cm2, but can vary from 0 to well over 100 dyn/cm2 elsewhere in the vasculature (Goldsmith and Turitto, 1986; Dobrin et al., 1989). While pulsing down the arterial tree, blood flow remains mostly laminar; however, it often becomes complex and/or disturbed (reversing and/or recirculating) at areas of arterial branching, triggering spatial and/or temporal gradients in shear stress (e.g., Figure II.1.6.2).

FIGURE II.1.6.2 Representation of flow features at the carotid bifurcation. (a) Change in wall shear stress throughout the course of the cardiac cycle at two locations within the carotid bifurcation, low shear (including recirculating flow) and high shear regions (MPSS, mean positive shear stress). (b) waveform of shear stress during one cardiac cycle (1 sec.) measured at the high shear stress region; (c) waveform of shear stress at the low shear stress region, showing reversing (recirculating) flow.

(Reprinted with permission from the Royal Society; White and Frangos, (2007). Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 362(1484), 1459–1467).

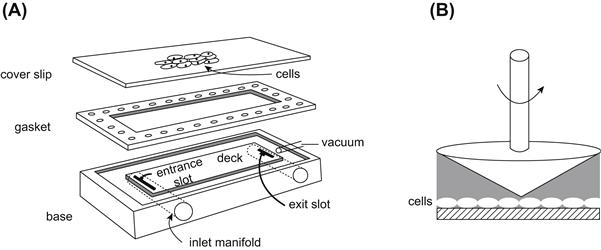

Endothelial cells have been studied extensively for their ability to respond to changes in shear stress. Two in vitro systems have been developed to characterize the response of endothelial cells to a variety of shear stresses: the parallel plate flow chamber; and the cone and plate system (Figure II.1.6.3). In the parallel plate model, cells are grown on a glass slide, which sandwiches a silicone gasket onto a polycarbonate parallel plate (Frangos et al., 1987). This creates a very small gap width through which tissue culture medium is circulated. The geometric dimensions are known, allowing for the calculation of the fluid shear stress from the flow rate. For a Newtonian fluid flowing through a parallel plate flow chamber with a rectangular geometry, the steady, laminar shear stress at the wall is:

(2)

(2)

FIGURE II.1.6.3 In vitro systems for studying the effects of shear stress on cells. (A) In the parallel plate system cells are grown on glass slides and mounted onto a parallel plate chamber. The gasket provides a known gap height. Fluid flows in the inlet, across the deck, and out the exit slot (B). In the cone and plate system cells are grown on a circular dish, which forms a viscometer at the bottom. A small fixed angle cone is rotated at a constant angular velocity providing a constant shear stress across the cells.

in which τw = wall shear stress, μ = viscosity, Q = flow rate, b = channel width, and h = channel height. By varying the chamber geometry, the flow rate or the viscosity, the entire physiological range of wall shear stresses can be investigated. The flow rate is varied using a syringe pump or gravity driven system to provide the desired wall shear stress across the cells. The cone and plate system consists of a tissue culture dish as the plate, and a fixed angle cone mounted to a motor that imparts an angular velocity. For small cone angles, the shear rate (and therefore the shear stress) is essentially constant throughout the flow field. Since the dimensions of this system are also characterized, the fluid shear stress can be calculated for a given angular velocity.

If the cell property studied responds to shear stress in a dose-dependent fashion (i.e., varies directly with the level of shear stress imposed), it is referred to as “shear stress-dependent.” If the property under study responds to changes in shear rate, but not directly with the level of shear stress imposed, it is referred to as “transport-dependent.” “Flow-dependent” can include both shear stress- and shear rate-dependent phenomena. The difference arises from inclusion of mass-transport phenomena (convection and diffusion) in flow-dependent processes, whereas the term “shear stress-dependent” refers to the mechanical force only. Differences between effects due to shear stress alone, and those due to mass and momentum transfer, can be examined by circulating media of different viscosities (e.g., with the addition of high molecular weight dextran).

Endothelial cells, in either of these in vitro shear stress systems, exposed to long-term (24 hours or greater) steady shear stress at arterial levels (10–25 dynes/cm2), as well as pulsatile non-reversing shear stress (Figure II.1.6.2b), have been shown to produce a more anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative phenotype than when exposed to pulsatile reversing conditions or low shear stress or to static culture (Figure II.1.6.2c) (McCormick et al., 2001; Dai et al., 2004; Chien, 2008; Yee et al., 2008). Acute responses to arterial shear stress include release of signaling molecules such as nitric oxide and prostacyclin, phosphorylation of membrane proteins, and activation of GTPases and tyrosine kinases (Frangos et al., 1985; White and Frangos, 2007). Released signaling molecules, such as prostacyclin and nitric oxide, can in turn act on smooth muscle cells to mediate vasorelaxation. Response of endothelial cells to arterial level shear stresses of 24 hours or longer include alignment of the actin cytoskeleton, movement of the microtubule organizing center toward the direction of flow, and cell elongation and alignment in the direction of flow (Eskin and McIntire, 1988; Orr et al., 2006).

Endothelial cells respond differently to reversing or oscillatory shear stress as compared to non-reversing shear stress. Steady or non-reversing shear stress transiently induces proinflammatory and proliferative pathways, which are subsequently downregulated by long-term exposure to shear stress. However, oscillatory or reversing shear stress results in sustained activation of these pathways, leading to the hypothesis that under steady shear stress cells adapt and downregulate these pathways, whereas under disturbed flow the continued changes in flow magnitude and direction lead to sustained activation (Dai et al., 2004; Orr et al., 2006; Chien, 2008). A summary of the changes induced by reversing shear stress as compared to non-reversing shear stress are summarized in Table II.1.6.1. The increases in cell proliferation, lipid metabolism, and inflammation observed in endothelial cells exposed to reversing shear stress in vitro suggest that in vivo disturbed hemodynamics may prime local sites for atherosclerosis. Consistent with biochemical differences, cells do not elongate or align in the direction of flow at sites of atherosclerosis (Figure II.1.6.4).

TABLE II.1.6.1 Comparison of the effects of reversing flow to non-reversing flow on endothelial gene expression and function

| Reversing Flow | Non-reversing Flow | |

| Flow Pattern | Fluid reversal, small net flow | No reversal, large net flow |

| Location in Arteries | Bifurcations and high curvature | Straight regions |

| Endothelial Cell Alignment | Not aligned | Aligned parallel to flow |

| Inflammatory Genes | Up-regulated | Down-regulated |

| Monocyte Adhesion | Increased | Decreased |

| Cell Proliferation | Increased | Decreased |

| Anti-oxidant Genes | Decreased | Increased |

| Vasodilating molecules | Decreased | Increased |

| Effect on Atherogenesis | Pro-atherogenic | Anti-atherogenic |

Adapted from Chien, S. (2008) Effects of disturbed flow on endothelial cells. Ann Biomed Eng, 36, 554–562.

FIGURE II.1.6.4 Arterial endothelial cell alignment in vivo (porcine) and in vitro (human). (a) Endothelial cell alignment in undisturbed unidirectional laminar flow in the descending thoracic aorta (LSS, laminar shear stress), and (b) absence of transition from alignment in disturbed flow adjacent to a branch of the aorta. In (b), a region of cell alignment changes abruptly to polygonal cell morphology beyond a line of flow separation (curved arrows) that marks the boundary of a disturbed flow region in which oscillating, multidirectional flow typically occurs (double-headed arrow). Scale bar in each panel = 15 μm. (c) Endothelial cell alignment under in vitro steady shear stress (15 dynes/cm2), and (d) reversing shear stress (modeled after the wall shear stress at the carotid sinus) is similar to in vivo alignment.

((a) and (b) reprinted with permission from Springer: Davies, P. F. (2008). Endothelial transcriptome profiles in vivo in complex arterial flow fields, Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 36, 563–570, 2008; (c) and (d) unpublished data (D. E. Conway).)

There is evidence that endothelial cells respond to shear stress within seconds. Rapid changes occur through the activation of ion channels, G-proteins, and stimulation of protein kinases (Davies et al., 2003; White and Frangos, 2007). Shear stress may act directly on the cell membrane to deform the cell surface and activate unknown sensor proteins. However, recent evidence has suggested that shear stress forces are transmitted by the cytoskeleton to intracellular locations where signaling can occur, such as intercellular junctions, focal adhesions, the nuclear membrane, and lipid rich regions of the cell membrane known as caveolae (Stamatas and McIntire, 2001; Davies et al., 2003; Boyd et al., 2003). In addition to remodeling of the cytoskeleton in response to shear stress there is also evidence of focal adhesion remodeling and activation of proteins at these adhesion sites (Davies et al., 2003), supporting the hypothesis that the majority of shear stress sensing is directly coupled to the cytoskeleton.

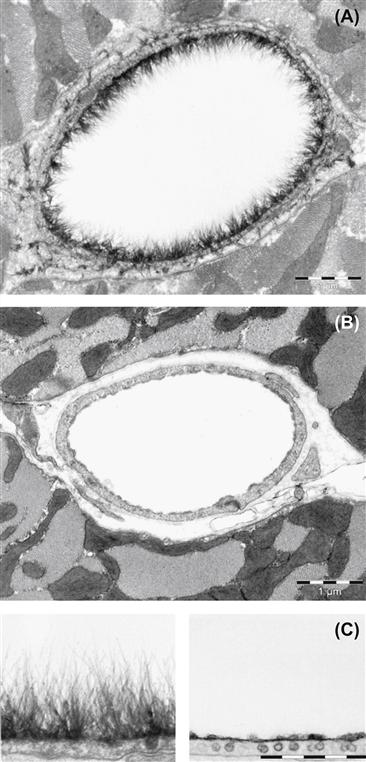

More recently, the glycocalyx has re-emerged as an important mechanosensor of shear stress in endothelial cells. The glycocalyx is an extracellular membrane-bound layer of glycoproteins and plasma proteins that has been shown to extend up to 500 μm from the endothelial cell membrane (Figure II.1.6.5). In vivo, this structure is large enough to prevent cells and even large plasma proteins from reaching the surface of the cell. Removal of key glycocalyx molecules results in a reduced response to shear stress (reduction in nitric oxide production, absence of cell elongation in response to flow, and loss of shear stress-induced suppression of cell proliferation), suggesting that the glycocalyx is an important mechano-sensor of fluid shear stress in endothelial cells (Tarbell and Pahakis, 2006). A reduction in the glycocalyx has also been observed in a number of disease states, including hypertension, inflammation, ischemia and reperfusion, hyperglycemia, and at known sites of atherosclerosis (internal carotid sinus). Furthermore, reduced glycocalyx expression has been correlated with increased leukocyte adhesion, suggesting that the glycocalyx may provide protection against atherogenesis (Van Teeffelen et al., 2007). Recently it has been suggested that in vitro endothelial cells do not form a hemodynamically relevant glycocalyx, highlighting the need for a better understanding of the formation and regulation of this potentially important mechano-sensitive extracellular structure (Potter and Damiano, 2008).

FIGURE II.1.6.5 The endothelial glycocalyx can extend up to 0.5 μm into the vessel lumen. (A) Electron microscopic overview of an Alcian blue 8GX-stained rat left ventricular myocardial capillary (bar = 1 μm). (B) After hyaluronidase treatment, before Alcian blue staining (bar = 1 μm). (C) Detailed pictures of glycocalyx on normal (left) and hyaluronidase-treated (right) capillaries (bar = 0.5 μm).

(Source: van den Berg, B. M. et al. (2003). Circ. Res., 92, 592–594.)

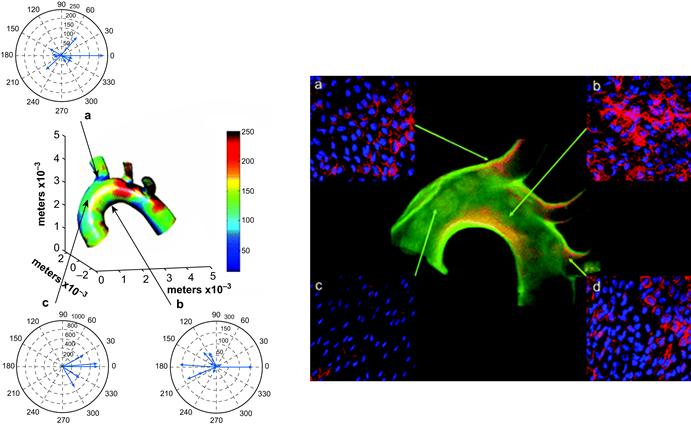

Animal models have further validated data generated from in vitro systems. Suo et al. used computational fluid dynamics to model the wall shear stress in the mouse aortic arch (Suo et al., 2007). Although the mouse vasculature has higher overall shear stresses than the human, inflammatory markers, such as intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), were upregulated at sites with low time-averaged shear stress and changes in shear stress direction (Figure II.1.6.6) (Suo et al., 2007). Microarray analysis of disturbed flow and undisturbed flow regions in the porcine aorta showed increased inflammatory cytokines and receptors in regions of disturbed flow (Passerini et al., 2004). These in vivo studies suggest that shear stress at sites of atherosclerosis may prime the endothelium toward an inflammatory state, which then may be exacerbated by additional risk factors (e.g., cholesterol, smoking, exercise).

FIGURE II.1.6.6 Regional differences in wall shear stress in the mouse aortic arch correlates with regional differences in VCAM-1 expression. Left: The computed, time-varying wall shear stress vectors are depicted at areas (a), (b), and (c) in one mouse aorta. The color coding indicates the mean wall shear stress distribution (defined as the wall shear stress magnitude averaged over the cardiac cycle). The vector diagrams indicate the time-varying changes in the direction and magnitude of wall shear stress throughout the cardiac cycle. There is a greater variation in the direction of the instantaneous wall shear stress vectors in areas (a) and (b), as can be seen in the polar plots of wall shear stress. Note that the relatively low mean wall shear stress zone at the inner curvature of the aortic arch (b), has instantaneous magnitudes of wall shear stress up to approximately 150 dynes/cm2, whereas values exceeding 600 dynes/cm2 were found along the lateral wall of the ascending aorta (c). Right: High expression of VCAM-1 protein correlates with areas of the aortic arch with low and time-varying shear stresses (a, b, and d) whereas VCAM-1 expression in the ascending aorta (c) is lower, consistent with unidirectional flow.

(Source: Suo, J. et al. (2007). Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 27, 346–351.)

Effect of Cyclic Strain on Blood Vessels

Along with momentum, pressure propagates as waves down the arterial tree, leading to a periodic circumferential tensile stress in the vessel lumen (Figure II.1.6.1). In vivo, blood pressure measures the variation in force against the blood vessel wall as the blood is ejected from the heart during each heartbeat (each cardiac cycle). In measuring blood pressure in humans, the brachial artery is occluded by a pressure cuff (attached to a sphygmomanometer), while the sound of the blood flow is measured downstream with a stethoscope. The pressure cuff is slowly loosened, allowing the pressure to decrease and the blood to flow downstream. The pressure at which the blood flow begins is the systolic pressure. As the pressure continues to decrease, the value at which the sound disappears is the diastolic pressure. Since the arterial wall is compliant, this periodic pressure difference gives rise to a cyclic wall strain. Since arteries and some synthetic substrates on which cells are cultured are elastic, cyclic strain can be measured as the percentage change in diameter between the systolic and diastolic pressures. In normal circulation, the internal diameter and, thus, circumference of large mammalian arteries increases cyclically between 2% and 18% over the cardiac cycle at a frequency of approximately 1 Hz (60 cycles/min) (Dobrin, 1978). The arterial cyclic strain can increase by 15% in hypertension (Gupta and Grande-Allen, 2006). Typical systole/diastole values in large human arteries range from 90/60 mmHg to 120/80 mmHg.

To study cyclic strain effects in vitro, cells must be cultured on a deformable substrate, usually silicone rubber or segmented polyurethane coated with extracellular matrix proteins, then subjected to cyclic deformation at a rate similar to the heart rate (1 Hz). Most frequently, custom built uniaxial strain devices are driven mechanically by an eccentric cam, which imposes a nearly uniform strain along the substrate at a frequency simulating the heart rate (1 Hz) (Frye et al., 2005; Yung et al., 2008). Custom built biaxial strain units have also been used (Kim et al., 1999). The mechanical forces generated in in vitro studies on uniaxial cyclic strain optimally include a “motion control” condition. “Motion control” controls for the reversing shear stress (less than 0.5 dyne/cm2) from fluid motion accompanying cyclic strain of the membrane. Some endothelial cells are more responsive to motion control than to cyclic strain (Sung et al., 2007). Cultured cells have been exposed to cyclic strain in commercially available Flexercell Strain Units (Flexcell International, Corp.), which can deform in uniaxial or biaxial modes (Matheson et al., 2007). These units are driven by vacuum pressure beneath 6-well plates with flexible elastomeric bottoms, on which cells are cultured, thus deforming substrate and cells (Haseneen et al., 2003). It should be noted that not only do the mechanical forces that impinge on a population of cultured cells alter their function, but also the substrate on which the cells are cultured may affect cell response. Cyclic strain has been shown to alter phenotype of cultured smooth muscle cells on polymeric scaffolds (Kim et al., 1999), and to cause differentiation of embryonic stem cells into smooth muscle cells (Shimizu et al., 2008).

Although the effects of shear stress and cyclic strain are most frequently studied independently of each other, recent work has suggested that the synchronization of the two forces when applied simultaneously can affect gene expression and morphology (Owatverot et al., 2005). The stress phase angle has been defined as the temporal phase angle between cyclic strain and wall shear stress (Figure II.1.6.7) (Dancu et al., 2004). The stress phase angle has been shown to be most negative at sites prone to atherosclerosis when compared to other regions of the vasculature, and can be made even more negative with hypertension (Dancu et al., 2004). Cells exposed to identical wall shear stress and cyclic strain, but at a stress phase angle of −180° instead of 0°, had reduced endothelial nitric oxide production and increased endothelin-1 production (Dancu et al., 2004), suggesting that asynchronous wall shear stress and cyclic strain could lead to endothelial cell dysfunction.

FIGURE II.1.6.7 Stress phase angle (SPA) is the phase shift between cyclic strain and wall shear stress.

(D. E. Conway drawing.)

Interstitial Fluid

Twenty percent of the mass of the human body consists of interstitial fluid, the fluid that surrounds most cells (Swartz and Fleury, 2007). This fluid is constantly in motion, driven by lymphatic drainage, which returns plasma that has leaked out of capillaries to the blood

Case Study Mechanical Forces in the Embryonic-Cardiovascular System

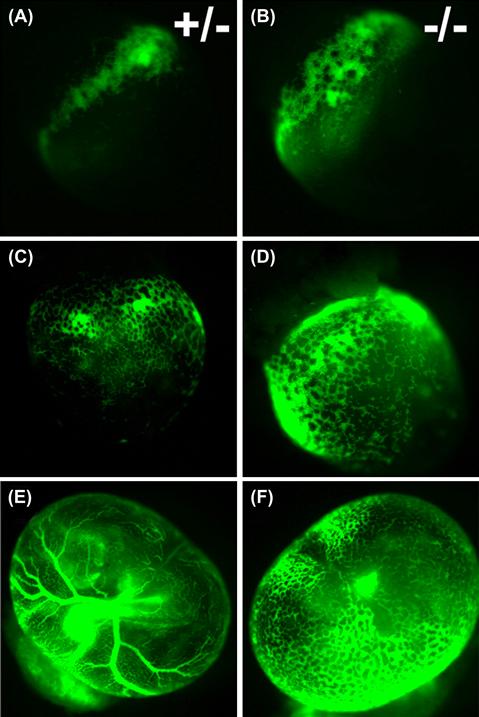

The embryonic circulatory system is highly dynamic, forming and remodeling while simultaneously providing blood flow to the developing organs. Until recently, the role of hemodynamic forces in the development of the heart and blood vessels was unknown. This case study shows the effects of hemodynamic forces on the vascular remodeling of the mouse embryo yolk sac (Lucitti et al., 2007). Endothelial cells in the yolk sac first assemble into a primitive vascular mesh network, but begin to remodel in the presence of flow into a network of branched, hierarchical network of large and small vessels that are surrounded by smooth muscle cells. Using a mouse knockout model (Mlc2a-null) that had impaired cardiac contractility (resulting in impaired flow and red blood cell movement), the authors showed that reduced blood flow led to impaired vessel remodeling. Reductions in the red blood cells in normal mice also impaired the vessel remodeling. To determine if the impaired vessel remodeling is due to lowered oxygen transport or reduced blood viscosity, the plasma in the mice with reduced red blood cells was supplemented with synthetic sugars to restore the viscosity to normal levels, which resulted in the development of a normal vascular system. Their results show that mechanical forces are essential for proper blood vessel development.

Heterozygous (A,C,E) and knockout (B,D,F) mouse embryos with fluorescently labeled red blood cells. At embryonic day 8.5, blood islands have formed in both wild-type (A) and Mlc2a-null (B) embryos, and red blood cells begin to circulate in both wild-type (C) and Mlc2a mutant (D) embryos. However, the vascular network fails to remodel by embryonic day 9.5 in the mutant embryos (F), as compared with wild-type (E).

(Reprinted with permission from The Company of Biologists, Lucitti, J. L., Jones, E. A., Huang, C., Chen, J., Fraser, S. E. & Dickinson, M. E. (2007). Vascular remodeling of the mouse yolk sac requires hemodynamic force. Development, 134, 3317–3326.)

through the lymphatic system (Figure II.1.6.8). The smallest lymphatic vessels are the lymph capillaries, which are found in most organs of the body, excluding the bone marrow and central nervous system. These capillaries start as blunt ends and come together to form larger contractile lymphatic vessels that have valves that prevent backflow, and smooth muscle cells that can provide contractility. The forces responsible for interstitial flow are hydrostatic and osmotic pressure differences (also known as Starling forces) between the blood, interstitium, and lymphatic system. Contractility by larger lymphatic vessels can further increase pressure gradients. The velocity of interstitial fluid is estimated to be 0.1 to 2 μm/s, but can be increased during inflammation (Swartz and Fleury, 2007). The resistance to interstitial fluid flow is affected by the specific composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM), cell density, and integrity of the lymphatic system; however, interstitial fluid pressure is also affected by external factors, such as movement, exercise, blood pressure, and hydration (Swartz and Fleury, 2007).

FIGURE II.1.6.8 Lymphatic vessels carry fluid away from the tissues. Lymphatic vessels start as blunt-ended capillaries and come together to form larger lymphatic vessels.

(Source: National Cancer Institute http://training.seer.cancer.gov/module_anatomy/unit8_2_lymph_compo.html.)

In addition to providing exchange of cell nutrients and wastes, interstitial flow has been shown to affect blood and lymphatic capillary morphogenesis, chondrocyte and osteocyte function, fibroblast differentiation, smooth muscle cell cytokine production, ocular function, morphogenesis in perfused three-dimensional cultures, and patterning in embryo development (see Box 2) (Nonaka, 2005; Swartz and Fleury, 2007). Interstitial flow can drive both mechanical and biochemical cellular responses by imparting mechanical forces, such as shear stress and cyclic strain, both on the cell surface and the extracellular matrix that is directly connected to the cellular cytoskeleton, and biochemical changes through redistribution of extracellular signaling molecules (Figure II.1.6.9) (Rutkowski and Swartz, 2007). In three-dimensional matrices with interstitial fluid flow of 1 μm/s, the shear stress at the cell surface has been estimated to average 6 × 10−3 dynes/cm2, with a peak shear stress of 1.5 × 10−2 dynes/cm2, over three orders of magnitude lower than the wall shear stress in a large artery (Rutkowski and Swartz, 2007). It is unclear if cells can directly sense such a low shear stress, and therefore may rely on the surrounding extracellular matrix to amplify the signals through shear-induced strain or alternatively the effects may be due to convective mass transfer of signaling molecules.

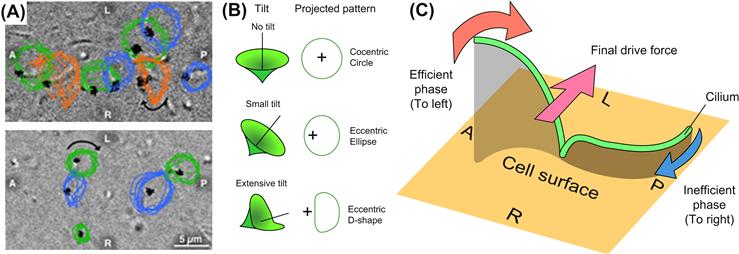

Box 2 Interstitial Fluid Flow Affects Vertebrate Embryo Patterning

Interstitial fluid flow has also been shown to be important in development and tissue morphogenesis. Nonaka et al. showed that in the mouse embryo the nodal cilia generate a unidirectional leftward flow of extraembryonic fluid which is the first step in the generation left–right asymmetry (Nonaka et al., 1998). Recent work has shown that convection, not just diffusion alone, of such signaling molecules can drive left–right asymmetry of internal organs (e.g., determining that the heart is located on the left side of the body). Reversal of this flow direction resulted in reversal of the asymmetry (Nonaka et al., 2002). It is currently unclear if nodal flow affects transport of signaling molecules or acts directly as a mechanical stress on the cells (Shiratori and Hamada, 2006). Morphological analysis of the nodal cilia has shown that the cilia are not completely perpendicular, but are instead tilted in the posterior direction (A and B) (Nonaka et al., 2005). This tilt, combined with the clockwise rotation of the cilia results in a more efficient stroke in the leftward direction, and a less efficient stroke in the rightward direction, resulting in a net flow in the left direction (C).

Left/right symmetry of vertebrate embryo. (A) Most cilia have a pattern consistent with the projection of a tilted cone (blue and green, see text) whereas some cilia move in a D-shape (orange). A, P, L, and R refer to anterior, posterior, left, and right sides of the node, respectively. The direction of cilia rotation was clockwise (arrows). (B) Relationship between movement of cilia and their projected images at various tilt angles. (C) Circular clockwise motion of a cilium can generate directional leftward flow if its axis is not perpendicular to the cell surface but tilted posteriorly. Due to distance from the cell surface, a cilium in the leftward phase (red arrow) drags surrounding water more efficiently than the rightward phase (blue arrow), resulting in a net leftward force (pink arrow).

(Images are from Nonaka, S., Yoshiba, S., Watanabe, D., Ikeuchi, S., Goto, T., et al. (2005). De novo formation of left–right asymmetry by posterior tilt of nodal cilia. PLoS Biol. 3(8): e268. This journal releases its work to the public domain).

FIGURE II.1.6.9 The direct effects of interstitial flow on cells. Interstitial flow can induce (a) fluid shear stress, σ, on the cell surface; (b) forces normal to the cell surface (F); (c) shear and normal forces to the pericellular matrix that is mechanically coupled to the cytoskeleton; and (d) redistribution of pericellular proteins (autocrine and paracrine signals) that bind cell receptors.

(Source: Rutkowski, J. M. & Swartz, M. A. (2007). A driving force for change: Interstitial flow as a morphoregulator. Trends in Cell Biology, 17(1), 44–50. Elsevier.)

Lymphatic flow has recently been shown to enable autologous chemotaxis, a mechanism whereby a cell can receive directional cues for cellular migration, but simultaneously can be the source of such cues (Fleury et al., 2006). Previously it was assumed that cells migrating towards a signaling concentration gradient were following a gradient secreted by an upstream cell or tissue. However, through autologous chemotaxis, subtle flows can create assymetrical pericellular protein concentrations and trancellular gradients that increase in the direction of fluid flow (Fleury et al., 2006). This mechanism could explain how leukocytes and tumor cells use gradients in interstitial fluid to locate and migrate to draining lymphatics (Rutkowski and Swartz, 2007).

In large arteries, the endothelial cells are the cells exposed directly to shear stress, while all the cell types in the vessel wall are exposed to cyclic strain. But when the endothelial cells are damaged, the hydraulic conductivity of an artery is dramatically increased. This increase in hydraulic conductivity leads to elevated interstitial flow through the artery wall. Models of interstitial flow in blood vessels with an intact endothelium have shown that medial smooth muscle cells are on average exposed to 1 dyne/cm2 shear stress, but the smooth muscle cells closest to the endothelial cells can experience a shear stress of 10 dynes/cm2, similar to the fluid shear stress directly imparted to the endothelial cells by blood flow (Tada and Tarbell, 2002). A study by Garanich et al. showed that increased shear stress enhanced the migratory properties of adventitial fibroblasts (Garanich et al., 2007). These fibroblasts have been reported to participate in the arterialization of capillaries, and also contribute to intimal hyperplasia (vessel thickening) that occurs in response to vessel injury. Changes in interstitial flow through the arterial wall may be important in mediating blood vessel wall remodeling.

Interstitial flow is important in the uptake of pharmaceuticals in local tissues or tumor delivery. Traditionally, therapeutics are given systemically, and therefore have been limited to small molecules with high diffusivities. However, the development of protein and antibody therapies and synthetic drug carriers, which are designed for selective uptake by a specific tissue, require a better understanding of the local interstitial transport in the target tissue. Tumors frequently have leaky blood vessels, in combination with a nonfunctional lymphatic system, resulting in increased interstitial fluid pressure compared to normal tissues (Swartz and Fleury, 2007). This can hinder anti-tumor therapies seeking to accumulate drugs selectively in tumor tissue. The increased interstitial pressure in the tumor leads to decreased convective forces across the blood vessel wall, as well as a decrease in pressure variation within in the tumor, resulting in decreased drug distribution in the tumor (Swartz and Fleury, 2007).

Bone and Cartilage

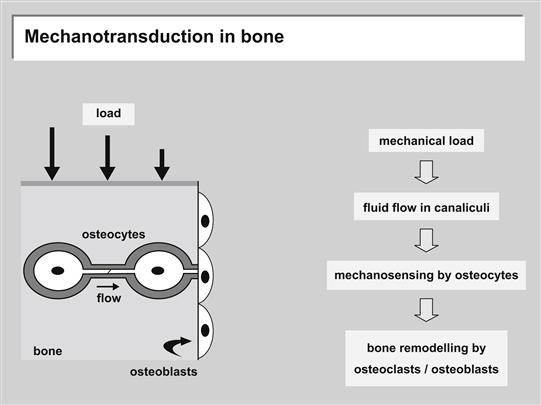

Bone is made up of three types of cells: osteocytes, which maintain function; osteoblasts, which build bone; and osteoclasts which degrade bone. These cells reside in a matrix of collagen and hydroxyapatite, a complex tetracalcium phosphate, which is produced by osteoblasts. The osteocytes are mechanosensors, which release prostaglandins in response to mechanical forces, principally shear stress (Jiang et al., 2007). They transmit signals to other bone cells and the matrix through thin channels in the matrix to influence bone remodeling.

Bone is a tissue that is constantly undergoing remodeling in response to mechanical loading, forming new bone parallel to the loading direction, and losing density in unstressed regions. Bone loss from sedentary lifestyle, limb paralysis or microgravity during space flight has provided conclusive in vivo evidence for the positive effects of physiological loading of skeletal tissues (Orr et al., 2006). Mechanical loading generates fluid shear stress, hydrostatic compression, and stretch on bone cells. The dense bone matrix resists compressive forces, limiting the transfer of force to the cells (Orr et al., 2006). Physiological strains are only 0.04–0.3%; however, in vitro it has been shown that strains must be 1–10% to induce cellular responses (Orr et al., 2006). Unmineralized matrix around osteocytes is more permeable than mineralized bone, creating lacuno-canalicular porosities for interstitial fluid flow. As a result, compressive forces generate pressure gradients that drive interstitial fluid flow in the matrix; these shear stresses have been estimated to be 8–30 dynes/cm2, similar to arterial wall shear stress (Orr et al., 2006). Interstitial fluid flow due to mechanical loading is thought to be the primary mechanism for action of mechanical forces on bone (Figure II.1.6.10) (Klein-Nulend et al., 2005). Although in vitro both osteoclasts and osteoblasts have been shown to respond to shear stress, the geometry of the lacuno-canalicular porosity suggests that interstitial fluid flow is preferentially sensed by the osteoclasts (Orr et al., 2006). Osteocytes respond to mechanical stimuli by secreting factors that can then, in turn, modulate both osteoblasts and osteoclasts (Klein-Nulend et al., 2005). Recent models, however, have suggested that the interstitial fluid flow applies drag forces to the pericellular matrix of the osteocyte that are 20 times larger than the fluid shear forces applied directly to the cell surface (Han et al., 2004). The fluid flow through the pericellular matrix induces strain on the actin filaments of the cytoskeleton, which results in strain amplification at the cellular level an order of magnitude greater than tissue-level strains. These recent models question the hypothesis that the regulatory mechanical force on osteocytes is fluid shear stress, and instead suggest that shear-induced strain may be the principal mechanotransducing force (Orr et al., 2006; Han et al., 2004).

Bone is a tissue that is constantly undergoing remodeling in response to mechanical loading, forming new bone parallel to the loading direction, and losing density in unstressed regions. Bone loss from sedentary lifestyle, limb paralysis or microgravity during space flight has provided conclusive in vivo evidence for the positive effects of physiological loading of skeletal tissues.

FIGURE II.1.6.10 Model for the transduction of mechanical strain to osteocytes in bone. Left: The osteocyte-lining cell network of bone tissue under stress (large arrows). Loading results in flow of interstitial fluid in the canalicular non-mineralized matrix (horizontal arrow).

(Source: Klein-Nulend, J., Bacabac, R. G. & Mullender, M. G. (2005). Mechanobiology of bone tissue. Pathologie Biologie, 53(10), 576–580. Elsevier.)

Exercise-stimulated bone remodeling may be the response of osteoblasts to interstitial fluid flow (Reich et al., 1990; Hillsley and Frangos, 1994). Furthermore, temporal gradients in interstitial fluid flow, imposed by pulsatile shear stress (designed to simulate mechanical loading) stimulate osteoblast proliferation in vitro (Jiang et al., 2002), whereas steady shear stress does not stimulate osteoblast signal transduction or proliferation. Exposure of mouse osteocytes and mixed-population human bone cells to pulsating shear stress in vitro increased prostaglandin and nitric oxide release, similar to the effects of shear stress on vascular endothelial cells, suggesting that there may be some similar mechanisms for sensing fluid flow (Klein-Nulend et al., 2005). Strain rate has been shown to be more important than strain amplitude in inducing bone formation in response to loading, supporting the hypothesis that bone formation is stimulated by dynamic rather than static loads (Klein-Nulend et al., 2005).

Cartilage, located on the articulating surfaces of joints, provides low friction for freely moving joints. In the growing embryo, cartilage is the precursor to bone. Cartilage cells (chondrocytes) secrete a matrix of collagen fibers embedded in mucopolysaccharide (e.g., chondroitin sulfate). Although cartilage is relatively asvascular compared with bone, cartilage responds to mechanical loading similarly to bone. Increased load leads to increased matrix production, resulting in stronger tissue. Cartilage must withstand tensile and shear forces in addition to compression (Kim et al., 1994). Most of the work on cartilage loading focuses on compression and hydrostatic pressure. Cyclic compression of explants (0.1 Hz, 2–3% compression) stimulated matrix synthesis by chondrocytes (Shieh and Athanasiou, 2003).

Summary

Nearly all mammalian cells and tissues are subject to mechanical forces. In the preceding pages we have highlighted the cardiovascular and skeletal systems adapted specifically to mechanical forces, to variations in blood flow and pressure, and to loadbearing, respectively. In vitro models have been employed to study how isolated endothelial and smooth muscle cells from arteries and veins respond to conditions of controlled shear stress and cyclic strain. Gene expression is sensitively regulated by alterations in shear stress and cyclic strain, which translates to functional changes in the cells. The elucidation of roles of different bone cell types has been clarified using in vitro models. We are just beginning to understand interstitial fluid flow in the lymphatic system, and the influence mechanical forces may have on cell migration and tumor growth.

In order to properly design biomaterials which successfully simulate native tissues, understanding the mechanical environment in which the biomaterial is implanted is important. Cells exposed to disturbed mechanical environments (e.g., reversing flow in blood vessels, compliance mismatch of blood vessel grafts, lack of weight-bearing on bone) typically have reduced function, and may promote the development of a pathological condition. In designing a biomaterial, we must attempt to recreate the mechanical environment that is to receive the implant for maximum success and long-term viability.

Bibliography

1. Alenghat FJ, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction: All signals point to cytoskeleton, matrix, and integrins. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:PE6.

2. van den Berg BM, Vink H, Spaan JA. The endothelial glycocalyx protects against myocardial edema. Circ Res. 2003;92(6):592–594.

3. Boyd NL, Park H, Yi H, et al. Chronic shear induces caveolae formation and alters ERK and Akt responses in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1113–H1122.

4. Chien S. Effects of disturbed flow on endothelial cells. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:554–562.

5. Dai G, Kaazempur-Mofrad MR, Natarajan S, et al. Distinct endothelial phenotypes evoked by arterial waveforms derived from atherosclerosis-susceptible and -resistant regions of human vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14871–14876 41.

6. Dancu MB, Berardi DE, Vanden Heuvel JP, Tarbell JM. Asynchronous shear stress and circumferential strain reduces endothelial NO synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 but induces endothelin-1 gene expression in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2088–2094.

7. Davies PF. Flow-mediated endothelial mechanotransduction. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:519–560.

8. Davies PF. Endothelial transcriptome profiles in vivo in complex arterial flow fields. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:563–570.

9. Davies PF. Hemodynamic shear stress and the endothelium in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:16–26.

10. Davies PF, Zilberberg J, Helmke BP. Spatial microstimuli in endothelial mechanosignaling. Circ Res. 2003;92:359–370.

11. Dobrin PB. Mechanical properties of arteries. Physiol Rev. 1978;58:397–460.

12. Dobrin PB, Littooy FN, Endean ED. Mechanical factors predisposing to intimal hyperplasia and medial thickening in autogenous vein grafts. Surgery. 1989;105:393–400.

13. Eskin SG, McIntire LV. Hemodynamic effects on atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1988;14:170–174.

14. Fleury ME, Boardman KC, Swartz MA. Autologous morphogen gradients by subtle interstitial flow and matrix interactions. Biophys J. 2006;91:113–121.

15. Frangos JA, Eskin SG, McIntire LV, Ives CL. Flow effects on prostacyclin production by cultured human endothelial cells. Science. 1985;227:1477–1479.

16. Frangos JA, McIntire LV, Eskin SG. Shear stress induced stimulation of mammalian cell metabolism. Biotech Bioeng. 1987;32:1053–1060.

17. Frye SR, Yee A, Eskin SG, Guerra R, Cong X, McIntire LV. cDNA microarray analysis of endothelial cells subjected to cyclic mechanical strain: Importance of motion control. Physiol Genomics. 2005;21:124–130.

18. Garanich JS, Mathura RA, Shi ZD, Tarbell JM. Effects of fluid shear stress on adventitial fibroblast migration: Implications for flow-mediated mechanisms of arterialization and intimal hyperplasia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H3128–H3135.

19. Glagov S, Zarins C, Giddens DP, Ku DN. Hemodynamics and atherosclerosis Insights and perspectives gained from studies of human arteries. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1988;112:1018–1031.

20. Goldsmith HL, Turitto VT. Rheological aspects of thrombosis and haemostasis: basic principles and applications ICTH-Report – Subcommittee on Rheology of the International Committee on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Thromb Haemost. 1986;55:415–435.

21. Gupta V, Grande-Allen KJ. Effects of static and cyclic loading in regulating extracellular matrix synthesis by cardiovascular cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:375–383.

22. Han Y, Cowin SC, Schaffler MB, Weinbaum S. Mechanotransduction and strain amplification in osteocyte cell processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16689–16694.

23. Haseneen NA, Vaday GG, Zucker S, Foda HD. Mechanical stretch induces MMP-2 release and activation in lung endothelium: Role of EMMPRIN. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L541–L547.

24. Hillsley MV, Frangos JA. Bone tissue engineering: The role of interstitial fluid flow. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1994;43:573–581.

25. Jiang GL, White CR, Stevens HY, Frangos JA. Temporal gradients in shear stimulate osteoblastic proliferation via ERK1/2 and retinoblastoma protein. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E383–E389.

26. Jiang JX, Siller-Jackson AJ, Burra S. Roles of gap junctions and hemichannels in bone cell functions and in signal transmission of mechanical stress. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1450–1462.

27. Kim BS, Nikolovski J, Bonadio J, Mooney DJ. Cyclic mechanical strain regulates the development of engineered smooth muscle tissue. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:979–983.

28. Kim YJ, Sah RL, Grodzinsky AJ, Plaas AH, Sandy JD. Mechanical regulation of cartilage biosynthetic behavior: physical stimuli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;311(1):1–12.

29. Klein-Nulend J, Bacabac RG, Mullender MG. Mechanobiology of bone tissue. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2005;53(10):576–580.

30. Lucitti JL, Jones EA, Huang C, Chen J, Fraser SE, Dickinson M. Vascular remodeling of the mouse yolk sac requires hemodynamic force. Development. 2007;134:3317–3326.

31. Matheson LA, Maksym GN, Santerre JP, Labow RS. Differential effects of uniaxial and biaxial strain on U937 macrophage-like cell morphology: Influence of extracellular matrix type proteins. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81:971–981.

32. McCormick SM, Eskin SG, McIntire LV, et al. DNA microarray reveals changes in gene expression of shear stressed human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8955–8960.

33. Nonaka S, Tanaka Y, et al. Randomization of left-right asymmetry due to loss of nodal cilia generating leftward flow of extraembryonic fluid in mice lacking KIF3B motor protein. Cell. 1998;95(6):829–837.

34. Nonaka S, Shiratori H, Y., Saijoh Y, Hamada H. Determination of left–right patterning of the mouse embryo by artificial nodal flow. Nature. 2002;418(6893):96–99.

35. Nonaka S, Yoshiba S, Watanabe D, et al. De novo formation of left–right asymmetry by posterior tilt of nodal cilia. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(8):e268.

36. Orr AW, Helmke BP, Blackman BR, Schwartz MA. Mechanisms of mechanotransduction. Dev Cell. 2006;10:11–20.

37. Owatverot TB, Oswald SJ, Chen Y, Wille JJ, Yin FC. Effect of combined cyclic stretch and fluid shear stress on endothelial cell morphological responses. J Biomech Eng. 2005;127:374–382.

38. Papadaki M, Eskin SG. Effects of fluid shear stress on gene regulation of vascular cells. Biotech Prog. 1997;13:209–221.

39. Passerini AG, Polacek DC, Shi C, et al. Coexisting proinflammatory and antioxidative endothelial transcription profiles in a disturbed flow region of the adult porcine aorta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2482–2487.

40. Potter DR, Damiano ER. The hydrodynamically relevant endothelial cell glycocalyx observed in vivo is absent in vitro. Circ Res. 2008;102:770–776.

41. Reich KM, Gay CV, Frangos JA. Fluid shear stress as a mediator of osteoblast cyclic adenosine monophosphate production. J Cell Physiol. 1990;143:100–104.

42. Rutkowski JM, Swartz MA. A driving force for change: Interstitial flow as a morphoregulator. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(1):44–50.

43. Shieh AC, Athanasiou KA. Principles of cell mechanics for cartilage tissue engineering. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31(1):1–11.

44. Shimizu N, Yamamoto K, Obi S, et al. Cyclic strain induces mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation into vascular smooth muscle cells by activating PDGF receptor beta. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(3):766–772.

45. Shiratori H, Hamada H. The left–right axis in the mouse: From origin to morphology. Development. 2006;133(11):2095–2104.

46. Singh N, Starnes BW, Andersen C. Successful angioaccess. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:1213–1228 xi.

47. Stamatas GN, McIntire LV. Rapid flow-induced responses in endothelial cells. Biotechnol Prog. 2001;17:383–402.

48. Sung HJ, Yee A, Eskin SG, McIntire LV. Cyclic strain and motion control produce opposite oxidative responses in two human endothelial cell types. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C87–C94.

49. Suo J, Ferrara DE, Sorescu D, Guldberg RE, Taylor WR, Giddens DP. Hemodynamic shear stresses in mouse aortas: Implications for atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:346–351.

50. Swartz MA, Fleury ME. Interstitial flow and its effects in soft tissues. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007;9:229–256.

51. Tada S, Tarbell JM. Flow through internal elastic lamina affects shear stress on smooth muscle cells (3D simulations). Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H576–H584.

52. Tarbell JM, Pahakis MY. Mechanotransduction and the glycocalyx. J Intern Med. 2006;259:339–350.

53. Van Teeffelen JW, Brands J, Stroes ES, Vink H. Endothelial glycocalyx: Sweet shield of blood vessels. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2007;17:101–105.

54. Wagner DD, Frenette PS. The vessel wall and its interactions. Blood. 2008;111:5271–5281.

55. White CR, Frangos JA. The shear stress of it all: The cell membrane and mechanochemical transduction. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362(1484):1459–1467.

56. Yee A, Bosworth KA, Conway DE, Eskin SG, McIntire LV. Gene expression of endothelial cells under pulsatile non-reversing vs steady shear stress; comparison of nitric oxide production. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:571–579.

57. Yung YC, Vandenburgh H, Mooney DJ. Cellular strain assessment tool (CSAT): Precision-controlled cyclic uniaxial tensile loading. J Biomech. 2008;42:178–182.