Chapter II.2.6

Blood Coagulation and Blood–Materials Interactions

The hemostatic mechanism is designed to arrest bleeding from injured blood vessels. The same process may produce adverse consequences when artificial surfaces are placed in contact with blood. These events involve a complex set of interdependent reactions between: (1) the surface; (2) platelets; and (3) coagulation proteins, resulting in the formation of a clot or thrombus which may subsequently undergo removal by; (4) fibrinolysis. The process is localized at the surface by opposing activation and inhibition systems, which ensure that the fluidity of blood in the circulation is maintained. In this chapter, a brief overview of the hemostatic mechanism is presented. Although a great deal is known about blood responses to injured arteries and blood-contacting devices, important relationships remain to be defined in many instances. More detailed discussions of hemostasis and thrombosis have been provided elsewhere (Forbes and Courtney, 1987; Stamatoyannopoulos et al., 1994; Gresle et al., 2002; Esmon 2003; Colman et al., 2005).

Platelets

Platelets (“little plates”) are non-nucleated, disk-shaped cells having a diameter of 3–4 μm, and an average volume of 10 × 10−9 mm3. Platelets are produced in the bone marrow, circulate at an average concentration of about 250,000 cells per microliter of whole blood, and occupy approximately 0.3% of the total blood volume. In contrast, red cells typically circulate at 5 × 106 cells per microliter, and may comprise 40–50% of the total blood volume. As discussed below, platelet functions are designed to: (1) initially arrest bleeding through formation of platelet plugs; and (2) stabilize the initial platelet plugs by catalyzing coagulation reactions leading to the formation of fibrin.

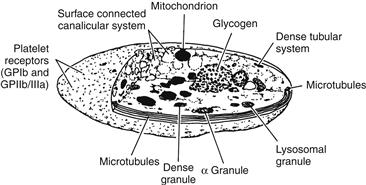

Platelet structure provides a basis for understanding platelet function. In the normal (nonstimulated) state, the platelet discoid shape is maintained by a circumferential bundle (cytoskeleton) of microtubules (Figure II.2.6.1). The external surface coat of the platelet contains membrane-bound receptors (e.g., glycoproteins Ib, and IIb/IIIa) that mediate the contact reactions of adhesion (platelet–surface interactions) and aggregation (platelet–platelet interactions). The membrane also provides a phospholipid surface which accelerates important coagulation reactions (see below), and forms a spongy, canal-like (canalicular) open network which represents an expanded reactive surface to which plasma factors are selectively adsorbed. Platelets contain substantial quantities of muscle protein (e.g., actin, myosin) which allow for internal contraction when platelets are activated. Platelets also contain three types of cytoplasmic storage granules: (1) α-granules, which are numerous and contain the platelet-specific proteins platelet factor 4 (PF-4) and β-thromboglobulin (β-TG), and proteins found in plasma (including fibrinogen, albumin, fibronectin, coagulation factors V and VIII); (2) dense granules which contain adenosine diphosphate (ADP), calcium ions (Ca2+), and serotonin; and (3) lysosomal granules containing enzymes (acid hydrolases).

FIGURE II.2.6.1 Platelet structure.

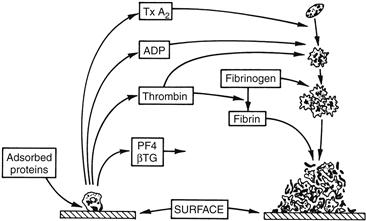

Platelets are extremely sensitive cells that may respond to minimal stimulation. Activation causes platelets to become sticky and change in shape to irregular spheres with spiny pseudopods. Activation is accompanied by internal contraction and extrusion of the storage granule contents into the extracellular environment. Secreted platelet products such as ADP stimulate other platelets, leading to irreversible platelet aggregation and the formation of a fused platelet thrombus (Figure II.2.6.2).

FIGURE II.2.6.2 Platelet reactions to artificial surfaces. Following protein adsorption to surfaces, platelets adhere and release α-granule contents, including platelet factor 4 (PF4) and β-thromboglobulin (β-TG), and dense granule contents, including ADP. Thrombin is generated locally through coagulation reactions catalyzed by procoagulant platelet surface phospholipids. Thromboxane A2 (TxA2) is synthesized. ADP, TxA2, and thrombin recruit additional circulating platelets into an enlarging platelet aggregate. Thrombin-generated fibrin stabilizes the platelet mass.

Platelet Adhesion

Platelets adhere to artificial surfaces and injured blood vessels. At sites of vessel injury, the adhesion process involves the interaction of platelet glycoprotein Ib (GP Ib) and connective tissue elements, which become exposed (e.g., collagen) and require plasma von Willebrand factor (vWF) as an essential cofactor. GP Ib (about 25,000 molecules per platelet) acts as the surface receptor for vWF (Colman et al., 2005). The hereditary absence of GP Ib or vWF results in defective platelet adhesion and serious abnormal bleeding.

Platelet adhesion to artificial surfaces may also be mediated through platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (integrin αIIbβ3), as well as through the GP Ib–vWF interaction. GP IIb/IIIa (about 80,000 copies per resting platelet) is the platelet receptor for adhesive plasma proteins which support cell attachment, including fibrinogen, vWF, fibronectin, and vitronectin (Gresle et al., 2002). Resting platelets do not bind these adhesive glycoproteins, an event which normally occurs only after platelet activation causes a conformational change in GP IIb/IIIa. Platelets which have become activated near artificial surfaces (for example, by exposure to factors released from already adherent cells) could adhere directly to surfaces through this mechanism (e.g., via GP IIb/IIIa binding to surface-adsorbed fibrinogen). Also, normally unactivated GP IIb/IIIa receptors could react with surface proteins which have undergone conformational changes as a result of the adsorption process (Chapter II.3.2). The enhanced adhesiveness of platelets toward surfaces preadsorbed with fibrinogen supports this view. Following adhesion, activation, and release reactions, the expression of functionally competent GP IIb/IIIa receptors may also support tight binding and platelet spreading through multiple focal contacts with fibrinogen and other surface-adsorbed adhesive proteins.

Platelet Aggregation

Following platelet adhesion, a complex series of reactions is initiated involving: (1) the release of dense granule ADP; (2) the formation of small amounts of thrombin (see below); and (3) the activation of platelet biochemical processes leading to the generation of thromboxane A2. The release of ADP, thrombin formation, and generation of thromboxanes all act in concert to recruit platelets into the growing platelet aggregate (Figure II.2.6.2). Platelet stimulation by these agonists causes the expression on the platelet surface of activated GP IIb/IIIa, which then binds plasma proteins that support platelet aggregation. In normal blood, fibrinogen, owing to its relatively high concentration (Table II.2.6.1), is the most important protein supporting platelet aggregation. The platelet–platelet interaction involves Ca2+-dependent bridging of adjacent platelets by fibrinogen molecules (platelets will not aggregate in the absence of fibrinogen, GP IIb/IIIa or Ca2+). Thrombin binds directly to platelet thrombin receptors, and plays a key role in platelet aggregate formation by: (1) activating platelets which then catalyze the production of more thrombin; (2) stimulating ADP release and thromboxane A2 formation; and (3) stimulating the formation of fibrin, which stabilizes the platelet thrombus.

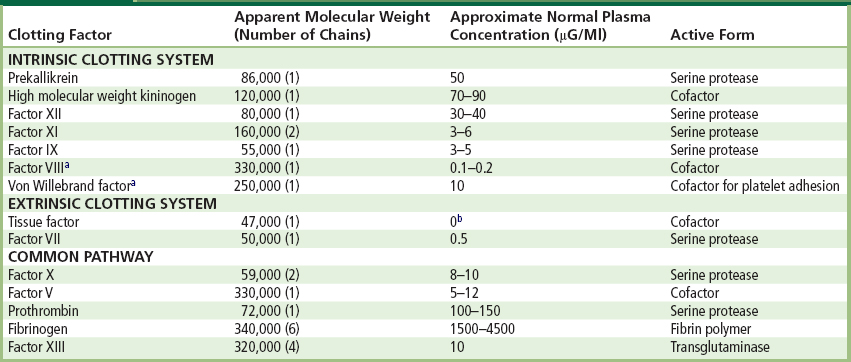

TABLE II.2.6.1 Properties of Human Clotting Factors

aIn plasma, factor VIII is complexed with von Willebrand factor, which circulates as a series of multimers ranging in molecular weight from about 600,000 to 2 × 107.

bThe tissue factor concentration in cell-free plasma is absent or minimal since tissue factor is an integral cell membrane-associated protein expressed by vascular and inflammatory cells.

Platelet Release Reaction

The release reaction is the secretory process by which substances stored in platelet granules are extruded from the platelet. ADP, collagen, epinephrine, and thrombin are physiologically important release-inducing agents, and interact with the platelet through specific receptors on the platelet surface. Alpha-granule contents (PF-4, β-TG, and other proteins) are readily released by relatively weak agonists such as ADP. Release of the dense granule contents (ADP, Ca2+, and serotonin) requires platelet stimulation by a stronger agonist, such as thrombin. Agonist binding to platelets also initiates the formation of intermediates that cause activation of the contractile–secretory apparatus, production of thromboxane A2, and mobilization of calcium from intracellular storage sites. Elevated cytoplasmic calcium is probably the final mediator of platelet aggregation and release. As noted, substances which are released (ADP), synthesized (TxA2), and generated (thrombin), as a result of platelet stimulation and release, affect other platelets and actively promote their incorporation into growing platelet aggregates. In vivo, measurements of plasma levels of platelet-specific proteins (PF-4, β-TG) have been widely used as indirect measures of platelet activation and release.

Platelet Coagulant Activity

When platelets aggregate, platelet coagulant activity is initiated, including expression of negatively charged membrane phospholipids (phosphatidyl serine) which accelerate two critical steps of the blood coagulation sequence: factor X activation; and the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin (see below). Platelets may also promote the proteolytic activation of factors XII and XI. The surface of the aggregated platelet mass thus serves as a site where thrombin can form rapidly in excess of the neutralizing capacity of blood anticoagulant mechanisms. Thrombin also activates platelets directly, and generates polymerizing fibrin which adheres to the surface of the platelet thrombus.

Platelet Consumption

In humans, platelets labeled with radioisotopes are cleared from circulating blood in an approximately linear fashion over time, with an apparent lifespan of approximately 10 days. Platelet lifespan in experimental animals may be somewhat shorter. With ongoing or chronic thrombosis that may be produced by cardiovascular devices, platelets may be removed from circulating blood at a more rapid rate. Thus steady-state elevations in the rate of platelet destruction, as reflected in a shortening of platelet lifespan, have been used as a measure of the thrombogenicity of artificial surfaces and prosthetic devices (Hanson et al., 1980, 1990).

Coagulation

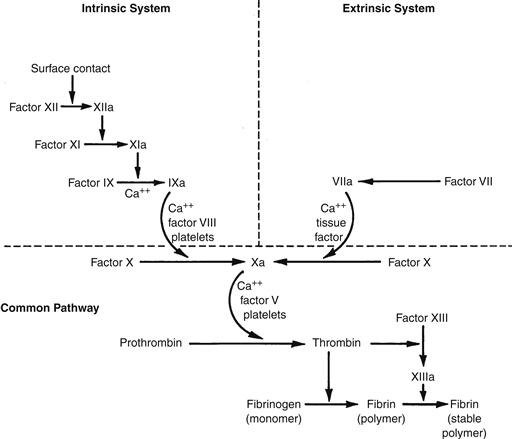

In the test tube, at least 12 plasma proteins interact in a series of reactions leading to blood clotting. Their designation as Roman numerals was made in order of discovery, often before their role in the clotting scheme was fully appreciated. Their biochemical properties are summarized in Table II.2.6.1. Initiation of clotting occurs either intrinsically by surface-mediated reactions or extrinsically through factors derived from tissues. The two systems converge upon a final common pathway which leads to the formation of thrombin and an insoluble fibrin gel when thrombin acts on fibrinogen.

Coagulation proceeds through a “cascade” of reactions by which normally inactive factors (e.g., factor XII) become enzymatically active following surface contact, or after proteolytic cleavage by other enzymes (e.g., surface contact activates factor XII to factor XIIa). The newly activated enzymes in turn activate other normally inactive precursor molecules (e.g., factor XIIa converts factor XI to factor XIa). Because this sequence involves a series of steps, and because one enzyme molecule can activate many substrate molecules, the reactions are quickly amplified so that significant amounts of thrombin are produced, resulting in platelet activation, fibrin formation, and the arrest of bleeding. The process is localized (i.e., widespread clotting does not occur) owing to dilution of activated factors by blood flow, the actions of inhibitors which are present or are generated in clotting blood, and because several reaction steps proceed at an effective rate only when catalyzed on the surface of activated platelets or at sites of tissue injury.

Figure II.2.6.3 presents a scheme of the clotting factor interactions involved in both the intrinsic and extrinsic systems, and their common path. Except for the contact phase, calcium is required for most reactions and is the reason why chelators of calcium (e.g., citrate) are effective anticoagulants. It is also clear that the in vitro interactions of clotting factors, i.e., clotting, is not identical with coagulation in vivo, which may be triggered by artificial surfaces and by exposure of the cell-associated protein, tissue factor. There are also interrelationships between the intrinsic and extrinsic systems, such that under some conditions “crossover” or reciprocal activation reactions may be important (Bennett et al., 1987; Colman et al., 2005).

FIGURE II.2.6.3 Mechanisms of clotting factor interactions. Clotting factors (proenzymes), identified by Roman numerals, interact in a sequential series of enzymatic activation reactions (coagulation cascade) leading to the amplified production of the enzyme thrombin, which in turn cleaves fibrinogen to form a fibrin polymer that stabilizes the clot or thrombus. Clotting is initiated by either an intrinsic or extrinsic pathway with subsequent factor interactions which converge upon a final, common path. The underlined factors are all activatable by the enzyme thrombin. The dotted line highlights the importance of feedback activation of FXI by thrombin, which results in increased thrombin production.

Mechanisms of Coagulation

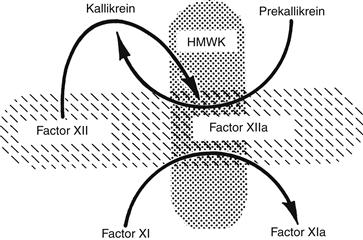

In the intrinsic clotting system, contact activation refers to reactions following adsorption of contact factors onto a negatively charged surface. Involved are factors XII, XI, prekallikrein, and high molecular weight kininogen (HMWK) (Figure II.2.6.4). All contact reactions take place in the absence of calcium. Kallikrein also participates in fibrinolytic system reactions and inflammation (Bennett et al., 1987). Although these reactions are well-understood in vitro, their pathologic significance remains uncertain. For example, in hereditary disorders, factor XII deficiency is not associated with an increased bleeding tendency, and only a marked deficiency of factor XI produces abnormal bleeding.

FIGURE II.2.6.4 Contact activation. The initial event in vitro is the adsorption of factor XII to a negatively charged surface (hatched, horizontal ovoid) where it is activated to form factor XIIa. Factor XIIa converts prekallikrein to kallikrein. Additional factor XIIa and kallikrein are then generated by reciprocal activation. Factor XIIa also activates factor XIa. Both prekallikrein and factor XI bind to a cofactor, high molecular weight kininogen (HMWK), which anchors them to the charged surface. Kallikrein is also responsible for the liberation of the vasoactive peptide bradykinin for HMWK, linking coagulation and inflammation.

A middle phase of intrinsic clotting begins with the first calcium-dependent step, the activation of factor IX by factor XIa. Factor IXa subsequently activates factor X. Factor VIII is an essential cofactor in the intrinsic activation of factor X, and factor VIII first requires modification by an enzyme, such as thrombin, to exert its cofactor activity. In the presence of calcium, factors IXa and VIIIa form a complex (the “tenase” complex) on phospholipid surfaces (expressed on the surface of activated platelets) to activate factor X. This reaction proceeds slowly in the absence of an appropriate phospholipid surface, and serves to localize the clotting reactions to the surface (versus bulk fluid) phase. The extrinsic system is initiated by the activation of factor VII. When factor VII interacts with tissue factor, a cell membrane protein which may also circulate in a soluble form, factor VIIa becomes an active enzyme which is the extrinsic factor X activator. Tissue factor is present in many body tissues; is expressed by stimulated white cells and endothelial cells, and becomes available when underlying vascular structures are exposed to flowing blood upon vessel injury.

The common path begins when factor X is activated by either factor VIIa-tissue factor by or the factor IXa–VIIIa complex. After formation of factor Xa, the next step involves factor V, a cofactor which (like factor VIII) has activity after modification by another enzyme, such as thrombin. Factor Xa–Va, in the presence of calcium and platelet phospholipids, forms a complex (“prothrombinase” complex) which converts prothrombin (factor II) to thrombin. Like the conversion of factor X, prothrombin activation is effectively surface catalyzed. The higher plasma concentration of prothrombin (Table II.2.6.1), as well as the biological amplification of the clotting system, allows a few molecules of activated initiator to generate a large burst of thrombin activity. Thrombin, in addition to its ability to modify factors V and VIII and activate platelets, acts on two substrates: fibrinogen and factor XIII. The action of thrombin on fibrinogen releases small peptides from fibrinogen (e.g., fibrinopeptide A) which can be assayed in plasma as evidence of thrombin activity. The fibrin monomers so formed polymerize to become a gel. Factor XIII is either trapped within the clot or provided by platelets, and is activated directly by thrombin. A tough, insoluble fibrin polymer is formed by interaction of the fibrin polymer with factor XIIIa.

Control Mechanisms

Obviously, the blood and vasculature must have mechanisms for avoiding massive thrombus formation once coagulation is initiated. At least four types of mechanisms may be considered. First, blood flow may reduce the localized concentration of precursors and remove activated materials by dilution into a larger volume, with subsequent removal from the circulation following passage through the liver. Second, the rate of several clotting reactions is fast only when the reaction is catalyzed by a surface. These reactions include the contact reactions, the activation of factor X by factor VII tissue factor at sites of tissue injury, and reactions which are accelerated by locally deposited platelet masses (activation of factor X and prothrombin). Third, there are naturally occurring inhibitors of coagulation enzymes, such as antithrombin III, which are potent inhibitors of thrombin and other coagulation enzymes (plasma levels of thrombin–antithrombin III complex can also be assayed as a measure of thrombin production in vivo). Another example of a naturally occuring inhibitor is tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), a protein that, in association with factor Xa, inhibits the tissue factor–factor VII complex. Fourth, during the process of coagulation, enzymes are generated which not only activate coagulation factors, but also degrade cofactors. For example, the fibrinolytic enzyme plasmin (see below) degrades fibrinogen and fibrin monomers, and can inactivate cofactors V and VIII. Thrombin is also removed when it binds to thrombomodulin, a protein found on the surface of blood vessel endothelial cells. The thrombin–thrombomodulin complex then converts another plasma protein, protein C, to an active form which can also degrade factors V and VIII. In vivo, the protein C pathway is a key physiologic anticoagulant mechanism (Esmon, 2003; Colman et al., 2005).

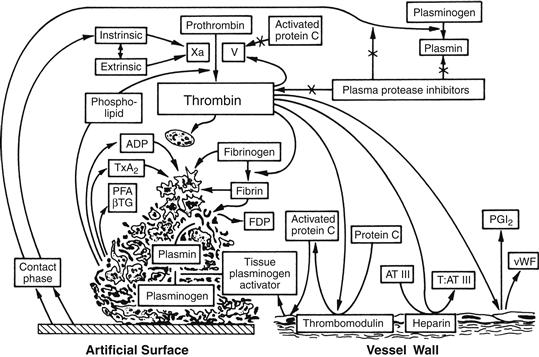

In summary, the platelet, coagulation, and endothelial systems interact in a number of ways which promote localized hemostasis while preventing generalized thrombosis. Figure II.2.6.5 depicts some of the relationships and inhibitory pathways which apply to blood reactions following contact with both natural and artificial surfaces.

FIGURE II.2.6.5 Integrated hemostatic reactions between a foreign surface and platelets, coagulation factors, the vessel endothelium, and the fibrinolytic system.

Fibrinolysis

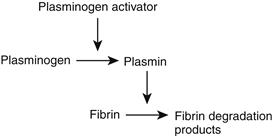

The fibrinolytic system removes unwanted fibrin deposits to improve blood flow following thrombus formation, and to facilitate the healing process after injury and inflammation. It is a multicomponent system composed of precursors, activators, cofactors, and inhibitors, and has been studied extensively (Forbes and Courtney, 1987; Colman et al., 2005). The fibrinolytic system also interacts with the coagulation system at the level of contact activation (Bennett et al., 1987). A simplified scheme of the fibrinolytic pathway is shown in Figure II.2.6.6.

FIGURE II.2.6.6 Fibrinolytic sequence. Plasminogen activators, such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or urokinase, activate plasminogen to form plasmin. Plasmin enzymatically cleaves insoluble fibrin polymers into soluble degradation products (FDP), thereby effecting the removal of unnecessary fibrin clot.

The most well-studied fibrinolytic enzyme is plasmin, which circulates in an inactive form as the protein plasminogen. Plasminogen adheres to a fibrin clot, being incorporated into the mesh during polymerization. Plasminogen is activated to plasmin by the actions of plasminogen activators which may be present in blood or released from tissues, or which may be administered therapeutically. Important plasminogen activators occuring naturally in humans include tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and urokinase. Following activation, plasmin digests the fibrin clot, releasing soluble fibrin-fibrinogen digestion products (FDP) into circulating blood, which may be assayed as markers of in vivo fibrinolysis (e.g., the fibrin D-D dimer fragment). Fibrinolysis is inhibited by plasminogen activator inhibitors (PAIs), and by a thrombin-activated fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI), which promotes the stabilization of fibrin and fibrin clots (Colman et al., 2005).

Complement

The complement system is primarily designed to effect a biological response to antigen–antibody reactions. Like the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems, complement proteins are activated enzymatically through a complex series of reaction steps (Bennett et al., 1987). Several proteins in the complement cascade function as inflammatory mediators. The end result of these activation steps is the generation of an enzymatic complex which causes irreversible damage (by lytic mechanisms) to the membrane of the antigen-carrying cell (e.g., bacteria).

Since there are a number of interactions between the complement, coagulation, and fibrinolytic systems, there has been considerable interest in the problem of complement activation by artificial surfaces, prompted in part by observations that devices having large surface areas (e.g., hemodialyzers) may cause: (1) reciprocal activation reactions between complement enzymes and white cells; and (2) complement activation which may mediate both white cell and platelet adhesion to artificial surfaces. Further observations regarding the complement activation pathways involved in blood–materials interactions are likely to be of interest.

Red Cells

Red cells are usually considered as passive participants in processes of hemostasis and thrombosis, although under some conditions (low shear or venous flows) red cells may comprise a large proportion of the total thrombus mass. The concentration and motion of red cells have important mechanical effects on the diffusive transport of blood elements. For example, in flowing blood, red cell motions may increase the effective diffusivity of platelets by several orders of magnitude. Under some conditions, red cells may also contribute chemical factors that influence platelet reactivity (Turitto and Weiss, 1980). The process of direct attachment of red cells to artificial surfaces has been considered to be of minor importance, and has therefore received little attention in studies of blood–materials interactions.

White Cells

The various classes of white cells perform many functions in inflammation, infection, wound healing, and the blood response to foreign materials. White cell interactions with artificial surfaces may proceed through as yet poorly-defined mechanisms related to activation of the complement, coagulation, fibrinolytic, and other enzyme systems, resulting in the expression by white cells of procoagulant, fibrinolytic, and inflammatory activities. For example, stimulated monocytes express tissue factor, which can initiate extrinsic coagulation. Neutrophils may contribute to clot dissolution by releasing potent fibrinolytic enzymes (e.g., neutrophil elastase). White cell interactions with devices having large surface areas may be extensive (especially with surfaces that activate complement), resulting in their marked depletion from circulating blood. Activated white cells, through their enzymatic and other activities, may produce organ dysfunction in other parts of the body. In general, the role of white cell mechanisms of thrombosis and thrombolysis, in relation to other pathways, remains an area of considerable interest.

Conclusions

Interrelated blood systems respond to tissue injury in order to rapidly minimize blood loss, and later to remove unneeded deposits after healing has occurred. When artificial surfaces are exposed, an imbalance between the processes of activation and inhibition of these systems can lead to excessive thrombus formation, and an exaggerated inflammatory response. While many of the key blood cells, proteins, and reaction steps have been identified, their reactions in association with artificial surfaces have not been well-defined in many instances. Therefore, blood reactions which might cause thrombosis continue to limit the potential usefulness of many cardiovascular devices for applications in humans. Consequently, these devices commonly require the use of systemic anticoagulants, which present an inherent bleeding risk.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by research grant HL-31469 and from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Public Health Service, and by the ERC Program of the National Science Foundation under Award EEC-9731643.

Bibliography

1. Bennett B, Booth NA, Ogston D. Potential interactions between complement, coagulation, fibrinolysis, kinin-forming, and other enzyme systems. In: Bloom AL, Thomas DP, eds. Haemostasis and Thrombosis. 2nd ed.) New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1987:267–282.

2. Colman RW, Marder VJ, Clowes AW, George JN, Goldhaber SZ, eds. Hemostasis and Thrombosis. New York, NY: Lippincott; 2005.

3. Esmon CT. The protein C pathway. Chest. 2003;124(3 Suppl.):26S–32S.

4. Forbes CD, Courtney JM. Thrombosis and artificial surfaces. In: Bloom AL, Thomas DP, eds. Haemostasis and Thrombosis. 2nd ed.) New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1987:902–921.

5. Gresle P, Page CP, Fuster F, Vermylen J. Platelets in Thrombotic and Non-thrombotic Disorders. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

6. Hanson SR, Harker LA, Ratner BD, Hoffman AS. In vivo evaluation of artificial surfaces using a nonhuman primate model of arterial thrombosis. J Lab Clin Med. 1980;95:289–304.

7. Hanson SR, Kotze HF, Pieters H, Heyns A, du P. Analysis of 111- Indium platelet kinetics and imaging in patients with aortic aneurysms and abdominal aortic grafts. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:1037–1044.

8. Stamatoyannopoulos G, Nienhuis AW, Majerus PW, Varmus H. The Molecular Basis of Blood Diseases. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 1994.

9. Turitto VT, Weiss HJ. Red cells: Their dual role in thrombus formation. Science. 1980;207:541–544.