Chapter II.3.7

Large Animal Models in Cardiac and Vascular Biomaterials Research and Assessment

Introduction

The purpose of using animal models in preclinical evaluation of biomaterials is to provide a preliminary assessment of human safety and efficacy relative to the manufacturer claims and comparable technology that can be used as an appropriate control standard. Although absolute unequivocal results cannot be obtained regarding human safety and efficacy, use of animal models have long been employed and have positively effected changes that have resulted in improved health and increased longevity for humankind. The importance of preclinical investigation has been realized by many great investigators including Charles Darwin, who poignantly describes this link in a letter to a Swedish professor of physiology in 1881 (Darwin, 1959): “I know that physiology cannot possibly progress except by means of experiments on living animals, and I feel the deepest conviction that he who retards the progress of physiology commits a crime against mankind.”

The development of new technologies, including in vitro methods and computer modeling, that has occurred in the last few decades has enhanced the approach to the study of physiology. However, the use of in vivo models still remains a necessity in investigations into certain physiologic phenomena, especially those related to the pathophysiologic mechanisms of disease, as in vitro studies are limited to the assessment of durability of the test material and hemodynamic performance. Traditional small animal models (e.g., rats, mice, guinea pigs, hamsters, and rabbits) have provided the scientific community access to physiological in vivo models to study mechanisms relating to human disease and basic biological processes. For the evaluation of cardiac and vascular biomaterials, however, investigations using larger domestic animals have proven to be more appropriate as these models incorporate anatomical and physiological characteristics more closely resembling those observed in humans. These similarities allow for the development of models where devices are implanted in a site intended for clinical use (i.e., site-specific), and allow for a more accurate prediction of the safety and clinical efficacy of either a bioprosthetic device or a biomaterial.

In this chapter, we will focus on three commonly used animal models for in vivo biomaterials research and testing in cardiac and vascular surgery: pigs; cows; and sheep. The chapter will begin with current recommendations for in vivo preclinical evaluation of cardiac and vascular devices, in both traditional and minimally-invasive settings, will continue with a short discussion on responsible use of animals in the assessment of biomaterials and biomedical devices, and will be followed by specific considerations and examples of existing animal models for each species. Finally, we will discuss conventionally-placed devices and percutaneously-placed devices, as well as potential future directions. Figure II.3.7.1 shows representative cardiac valves that are widely used clinically.

FIGURE II.3.7.1 Cardiac valves used clinically. (A) St. Jude Medical®Regent™ bileaflet mechanical aortic valve. (B) Sorin Mitroflow® bioprosthetic aortic valve. (C) Edwards Sapien bioprosthetic valve for percutaneous implantation. (Used with permission.)

Recommendations for Preclinical Assessment

The purpose of preclinical in vivo assessment is to provide an estimation of device safety (primary) and efficacy (secondary) in humans. This assessment is a mandatory requirement prior to the initiation of the next phase of device evaluation, namely clinical trials. The International Standards Organization (ISO), in conjunction with the American National Standards Institute, Inc. (ANSI) and the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI), has defined regulatory requirements governing preclinical studies which are specific to cardiovascular valve prostheses (ANSI/AAMI/ISO 5840:2005 (AAMI, 2005)), and to cardiovascular implants and tubular vascular prostheses (ANSI/AAMI/ISO 7198:1998/2001/(R)2004 (AAMI, 2001)). These documents govern all aspects of evaluation, from the initial in vitro assessment to the final packaging requirements. These requirements must be reviewed and, if necessary, revised every five years to reflect the advancements in the rapidly evolving fields of biomaterial and bioprosthetic device development. In addition, these requirements also strive to meet the challenge of ensuring that compliant preclinical assessments provide an accurate correlation of in vitro and in vivo performance, as well as a basis for comparison with future clinical results.

The preclinical assessment of biomaterials and bioprosthetic devices is the final investigational step prior to human implantation, thus evaluation must ensure that the devices assessed will perform at least as well in humans as those bioprostheses currently in use. We will limit our discussion to the established standards for in vivo preclinical evaluation of cardiac valvular and tubular vascular prostheses, both those placed conventionally and those placed percutaneously. The standards that apply to the experimental methodology used in the investigation and the specific study criteria that must be met, as well as required results documentation, will be delineated. Following this, a short discussion on the future directions of these standards and the predicted impact these changes may have on the study of these types of devices will be presented.

Current Recommendations

Cardiac Devices

Rationale

Safety assessment is the primary outcome of preclinical studies, with an emphasis on risk analysis in humans. Prior to clinical trials, all new or modified heart valve designs must be evaluated in a standardized, reproducible animal model. The evaluation must use adequate numbers of the experimental devices and concurrent controls implanted in a site-specific fashion, and must involve the use of risk analysis. Neither endpoints nor a defined animal model of preclinical assessment are specified in regulatory documents. Inherent in the preclinical assessment is an evaluation of the performance characteristics of cardiac devices, such as surgical handling characteristics, hemodynamic performance, and the development of valve-related pathology. Although it is not feasible to assess the long-term durability of a cardiac device using an animal model, valuable hemodynamic performance and biological compatibility data can be obtained. Additionally, in vivo testing may expose unanticipated side-effects of the device. ISO 5840 guidelines were developed to guide designers and investigators, and to ensure that new or modified cardiac valvular prostheses are assessed in a uniform manner.

Major changes between ISO 5840:2005 (AAMI, 2005) and its previous iteration, ISO 5840:1996 (AAMI, 1996), include:

1. Incorporating risk-based analysis and placing the responsibility on the manufacturer to continually evaluate both known and theoretical risks of the device;

2. Detailing best practice methods for verification testing appropriate to heart valve substitute evaluation;

3. Requiring a collaborative environment between the device developer and the regulatory body regarding safety and device performance; and

4. Outlining a system to assist a surgeon in selecting a device of appropriate size for placement in a patient.

Methods

Current regulatory requirements defined in ISO 5840 have been revised to specifically address risk analysis in devices representing major design or material changes, recognizing that such changes may result in dramatic (sometimes catastrophic) changes in performance and safety. The changes to guidelines call for expansion of study design to include a minimum of 10–15 experimental devices of clinical quality, with 2–4 concurrent control devices implanted in each clinically-intended surgical site, followed by subsequent comprehensive observation for at least six months. ISO 5840 requirements state that control devices must be clinically-approved devices of a design similar to that of the experimental device, and must be constructed from the same materials, which can be problematic in the case of a newer polymeric material. Minor modifications to devices (i.e., a sewing ring alteration) may involve a less rigorous assessment, as determined by risk analysis, although it is important to accurately distinguish between a major and a minor modification (see Box 1).

Box 1

In an effort to render a mechanical heart valve more resistant to endocarditis, the sewing ring was redesigned to include impregnation with antibiotics. During in vivo preclinical assessment, unexpected thromboses were observed with each valve tested (see Figure II.3.7.2), resulting in the failure of this modified valve to proceed to clinical trials. Risk analysis is a critical component of preclinical assessment, and no assumptions can be made as to the importance of any modification to a device. Although there is biological variability, especially given the relatively low numbers of animals, it is important to separate outcomes that are device-related from those that are the result of the animal model chosen. However, a catastrophic failure, such as this example, must result in a complete review of the in vivo testing results, and reassessment of the suitability of the animal model chosen.

FIGURE II.3.7.2 Example of a thrombosed mechanical valve in which a minor modification to the sewing ring resulted in an unexpected outcome of the preclinical assessment and failure of the valve.

In all preclinical assessments, performance criteria must take into consideration animal–device interactions, individual biological variation, and the small numbers of devices implanted for evaluation. In addition, a complete pathological examination of all animals evaluated must be performed by a veterinary pathologist to distinguish model versus device complications. It is sometimes difficult to completely separate the outcomes due to the device from model-related outcomes. The exception is when the assessment of a device results in catastrophic failure.

Further specifications require each animal in which a cardiac device has been implanted to undergo a postmortem examination. This ensures that data will be obtained from all animals; whether or not they survive for the suggested minimum time of six months. An evaluation of hemodynamic performance of the device during or after the implantation period must be performed. This assessment should include measurement of the pressure gradient across the implanted device at a cardiac index of approximately 3 L/min/m2 to mimic human conditions. Additionally, an assessment of resting cardiac output and prosthesis regurgitation should be performed. A pathological evaluation of the study animals should also be performed, and should include an assessment of the major organs for valve-related pathology; an evaluation for any device-related hematological consequences; and an assessment of any structural changes of the heart valve substitute.

ISO 5840 criteria for the evaluation in preclinical in vivo assessment are specific to acute or chronic settings, both of which provide valuable information. Acute settings focus on hemodynamic performance, ease of surgical handling, and acoustic characteristics of the implanted device. Chronic settings include the previously mentioned issues as well as hemolysis, potential thromboembolic complications, calcification, pannus formation/tissue ingrowth, structural deterioration and non-structural dysfunction, erosion caused by cavitation, and assessment of valve and non-valve related pathology (ANSI/AAMI/ISO 5840:2005, Annex G (AAMI, 2005)).

Previous ISO standards (ANSI/AAMI/ISO 5840:1996) relating to preclinical assessment of a device outlined requirements stating that at least six animals should be implanted with the experimental device or test article, and an additional two animals should be implanted with control devices for each assessment. A follow-up of at least six months was required for animals implanted with the test article which needed to include hemodynamic measurements, serial blood samples, and extensive pathological evaluation. No animal model was specified in the standards. These minimum requirements are rarely sufficient for adequate assessment of a bioprosthetic device, but may retain some value in the assessment of devices in which only minor modifications have been made, as long as concurrent controls are included and historical data is considered. The design of a preclinical assessment according to the updated regulatory requirements now must consider risk analysis, which is based on the device as well as the manufacturer claims attributed to it, and whether the device is novel or just an incremental modification of an existing device. Inherent in the risk-based approach outlined in the current ISO standards is encouragement for the manufacturer to strive for continued improvements in device design, as well as to ensure safety and efficacy of a device with less reliance on years of clinical assessment for verification of effectiveness.

Reporting

Documentation of results from preclinical evaluations is integral to this process and should be in the form of an official written report describing findings of the investigation in detail. This report should include the name of the institution(s) and investigator(s) involved in the study. A detailed description of the animal model used in the investigation, and the rationale for its use, should also be included. A pretest health assessment, including study animal age at the time of implantation, should also be included for each animal used in the study. A description of the operative procedure, including the suture technique, the orientation of the heart valve substitute, and any operative complications, must be detailed. Descriptions of any adjuvant procedures the animals underwent during the study period (e.g., phlebotomy, angiography) should also be provided. The results of all blood tests, including a statement of the time elapsed between implantation and procurement of the sample should be provided. Blood tests should include an evaluation of the hematologic profile (with emphasis on hemolysis), and blood chemistries. Additionally, the report should include a subjective assessment of specific surgical handling characteristics of the device and any accessories. This assessment should include a discussion of unusual and/or unique attributes the device might possess. The report must contain a complete list of medications administered to the animals during the study period. Finally, the report should contain the results obtained from the hemodynamic studies to assist in the assessment of hemodynamic performance.

Pathologic documentation should include a gross and microscopic report on each animal in which a heart valve substitute was implanted, including any animal that did not survive the minimum post-implantation period. Documentation should include visual records of the heart valve substitute in situ, and evidence of any thromboembolic events occurring in the major organs. The cause of death of any animal that was not euthanized at the study endpoint must be investigated and reported. Detailed examination of the explant must be performed, with specific attention to any structural changes in the device. If appropriate, further in vitro functional studies of the heart valve substitute should be undertaken, such as hydrodynamic testing.

Pathologic assessment is crucial in the evaluation of the safety profile of the test device, and input from both a veterinary pathologist and a physician pathologist are ideal and necessary for the complete assessment of device safety. It is the role of the veterinary pathologist to decipher whether any pathologic findings are due to device malfunction or the inherent physiology of the animal. It is then the role of the physician pathologist to assess the in situ findings, and correlate them with a potential clinical performance in humans.

Vascular Devices

Rationale

As with cardiac devices, the purpose of in vivo preclinical testing of vascular prostheses is to evaluate the characteristics of a prosthetic that are difficult, if not impossible, to obtain using in vitro testing models. The capacity of the prosthesis to maintain physiologic function when used in the circulatory system, the biologic compatibility of the prosthetic, and the surgical handling characteristics of the prosthesis are all important features that can be evaluated using an in vivo model and cannot be obtained with in vitro testing methods. This testing is not intended to demonstrate the long-term performance of the prosthesis, but rather the short-term (less than 20 weeks) response and patency of the prosthesis being investigated.

Methods

In designing an experimental protocol that will ensure clinical relevance, researchers should consider the intended application of the device being studied, as well as the necessary diameter and length of the prosthesis. Additionally, investigators should reflect on any specific biological characteristics of the chosen animal model, and the impact of those characteristics on their conclusions. Current ISO requirements state that a rationale for the use of a particular species, the site of implantation, the selection of a control prosthesis, the method and interval of patency observations, and the number of animals used in each group being studied be provided. Each type of prosthesis shall have been tested by implantation at the intended, or at an analogous, vascular site in not fewer than six animals for not less than 20 weeks in each animal, unless a justification for a shorter-term study can be provided. A prosthesis must not be tested in the species from which it was derived, unless appropriate justification can be provided. Angiography or Doppler should be used to monitor the duration of patency for each prosthesis, and the results recorded. Each investigation should include a control group in which a clinically-approved vascular prosthesis is implanted and studied in the same fashion as the experimental prosthesis.

Preoperative data should include the sex and weight of the animal, documentation of satisfactory preoperative health status, and any preoperative medications. Operative data must include the name of the implanting surgeon and a detailed description of the surgical procedure, to include the type and technique used in performing the proximal and distal anastomoses. The in situ length and diameter of the prosthesis, in addition to any adverse intraoperative events (e.g., transmural blood leakage), must also be documented. Postoperative medications, patency assessments (method and interval from implantation), and any adverse event or deviation from protocol must be noted. Loss of patency before the intended study duration does not necessarily exclude the animal from the study population used to assess prosthetic function and host tissue response. Reports from all animals implanted with either test or control prostheses, including those excluded from the final analyses, shall be recorded. Termination data should include an assessment of prosthesis patency (documenting the method used), and an assessment of prosthesis explant pathology.

Reporting

At the conclusion of the study, a detailed report should be compiled in which the study protocol is delineated. The report should include: the rationale for selection of animal species; implantation site; control prosthesis; method of patency assessment; and the intervals of observation. Additionally, documentation of sample size and pertinent operative, perioperative, and termination data must be presented. The results should include the patency rates and any adverse event that was encountered during the study interval, and should be compared between the study and control groups. All animals entered into the study must be accounted for in the report. If data are excluded a rationale must be provided. A summary of the gross and microscopic pathology, including photographs of the prosthesis in situ and micrographs, should also be provided. In addition to these objective results, a subjective statement of the investigator’s opinion of the device must be included. Again, for this reason, it is important to include the input of a veterinary pathologist to decipher device malfunction from animal physiology, as well as a physician pathologist to correlate pathologic findings with potential clinical performance. Finally, conclusions drawn from the study and a summary of the data auditing procedures should be documented.

Responsible Use of Animals

Introduction

As discussed in greater detail in Chapter II.3.6 of this book (Animal Surgery and Care of Animals), there are two basic principles governing the use of animals in research, education, and testing: (1) scientific reliance on the use of live animals should be minimized; (2) pain, distress, and other harm to laboratory animals should be reduced to the minimum necessary to obtain valid scientific data. Strict adherence to these basic ethical principles will not only enhance the quality of each in vivo preclinical evaluation, but will also ensure that current and future generations of scientists will be able to employ all valid tools available to predict clinical safety of either new or modified medical devices and other technology designed to improve human health.

Investigator and Institutional Responsibilities

When considering appropriate animal models for biomaterials research, the investigator and sponsoring institution should first assess their responsibilities with respect to federal, state, and local laws and regulations. Additionally, given the growing public and political sensitivity to the use of research animals, all laboratories using animals must recognize and comply with current definitions of humane animal care and use. The importance of this issue is reflected in a resolution adopted by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, February 19, 1990. This section briefly presents legal obligations and responsibilities of both the institutional administration’s veterinary care program and the investigator, and provides some practical guidelines for responsible use of laboratory animals.

The Animal Welfare Act (Public Law 89-544, as amended) provides federal regulations governing laboratory animal care and use (Title 9 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Chapter 1, subchapter A: Animal Welfare, Parts 1, 2, 3) which are enforced by the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), US Department of Agriculture. The Animal Welfare Act covers specific species including dogs, cats, non-human primates, guinea pigs, hamsters, rabbits, and “any other warm-blooded animal, which is used or is intended for use in research, teaching, testing, experimentation …” (9 CFR subchapter A, Part 1, Section 1.1). Species specifically exempt from the Animal Welfare Act include birds, rats, and mice bred for use in research, as well as horses and livestock species used in agricultural research. Institutions using species covered by the Animal Welfare Act must be registered by APHIS. Continued registration is dependent on the submission of annual reports to APHIS by the institution, as well as maintaining a satisfactory rating upon inspection of the institution’s animal facility during unannounced site visits by APHIS inspectors. The Animal Welfare Act provides specifications for animal procurement (i.e., from licensed suppliers), husbandry, and veterinary care that are used to determine compliance with the Animal Welfare Act. The annual report supplied to APHIS should contain a list of all species and the numbers of animals used by the institution in the previous year. The animals listed in the annual report must be categorized by the level of discomfort or pain they were thought to experience in the course of the research, education or testing process they were used for.

In 1985 amendments were made to the Animal Welfare Act (7 U.S.C. 2131, et seq.) and ultimately implemented on October 30, 1989, August 15, 1990, and March 18, 1991. These amendments extended the Act to require institutions to perform administrative review and provide a mechanism to control animal research programs (Federal Register, Vol. 54, No. 168, pp. 36112–36163; Vol. 55, No. 36, pp. 28879–28881; Vol. 56, No. 32, pp. 6426–6505). Specifically, the new regulation requires that all animal research protocols be reviewed and approved by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) before the initiation of the study. Furthermore, the submitted protocols must state in writing that less harmful alternatives were investigated, with justification as to why those methods are not suitable, and that the proposed research is not unnecessarily duplicative. Additional requirements increase the scope of husbandry requirements for laboratory dogs and non-human primates.

The other relevant federal body is the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The Health Research Extension Act of 1985 (Public Law 99-158) required the director of NIH to establish guidelines for the proper care of laboratory animals, and gave IACUC oversight of that care. Broad policy is described in the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH, 2002), which identifies the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH, 1985a) as the reference document for compliance. This policy applies to all activities involving animals either conducted or supported by the US Public Health Service (PHS). An institution cannot receive funding from the NIH or from any other PHS agency for research involving the use of animals, without a statement of assurance on file with the PHS Office for Protection from Research Risks (OPRR) ensuring compliance with these guidelines.

As required by the Animal Welfare Act, PHS policy mandates that each institution provide an annual update on animal research use and IACUC review of animal protocols and facilities to be submitted to the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW) within the NIH. Unlike the Animal Welfare Act, however, the PHS policy covers all vertebrate species, does not include an enforcement arm for routine inspections (but does provide for inspection in cases of alleged misconduct), and penalizes noncompliant institutions by withdrawing funding support.

State and local laws and regulations may also affect animal research programs. This legislation imposes restrictions on the acquisition of cats and dogs from municipal shelters. Within the past decade several states have also enacted registration and inspection statutes similar to the Animal Welfare Act. In several states, court rulings have required IACUC reports and deliberations at state-supported institutions to be conducted in public (e.g., Florida, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Washington).

Housing and Handling

The physical and psychological well-being of laboratory animals is determined in large part by their environment. Careful attention to housing and handling of any investigational animal is crucial to avoid improper handling or care which may result in exposure of the animal to undue stress. The Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources of the National Academy of Sciences publishes a detailed guide with specific recommendations for the housing of many laboratory animal species (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Commission on Life Sciences, 2011). Adequate assessment of available facilities and their compliance with these regulations must be considered an essential component of any animal investigation. This assessment should be done not only for regulatory affairs compliance, but also for scientific accuracy, as data obtained from subjects that are not cared for properly may be inaccurate.

Euthanasia

In addition to housing and handling, investigators must become familiar with the methods appropriate to the practice of humane euthanasia techniques. Indications for the application of euthanasia in a study include such inviolable situations such as: (1) study protocol completion; or (2) undue suffering of an individual study subject that may be displaying cachexia, anorexia or a moribund state. In this phase of the investigation, as in all other phases of an animal investigation, great care should be taken to avoid subjecting the animal to undue stress. Humane euthanasia techniques used should result in rapid unconsciousness followed by cardiac and respiratory arrest. The 1993 Report of the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA, 1993) provides descriptions of acceptable techniques for euthanasia, and is an invaluable resource for investigators in the process of designing and performing a study; the most recent revision of these guidelines was in 2007, with a minor update in 2009 (AVMA, 2007; Nolen, 2009).

Animal Models and Species Consideration

Choice of an Appropriate Animal Model

In determining which model is most appropriate for an in vivo assessment to best evaluate the likely human response to the device, it is first necessary and most important to outline the clinical goals of the bioprosthetic test device and choose the animal model that has been shown to permit control of the greatest number of variables. The closer the in vivo assessment parallels a clinical situation, the more clinically applicable are the results of the assessment. That being said, the sheep is often the superior model in cardiovascular research, as it is relatively easy to control many variables. In addition, the physiological parameters of sheep often approximate the human condition, especially with respect to thrombogenicity. In contrast, swine tend to be exquisitely sensitive to exogenous anticoagulation therapy in an unpredictable fashion. In our experience, when anticoagulation therapy is utilized in swine, the results generated are a series of anecdotes that relate more to each individual animal’s differing level of thrombogenicity, rather than to a herd response to a device. If anticoagulation therapy is necessary, it is most important to consider the entire herd of test and control subjects, and dose them with equal amounts of anticoagulation therapy so that any effect this may have on the study outcome will be demonstrated in each of the animals. However, an ideal study protocol should incorporate no anticoagulation therapy for any animal, because it naturally crafts a more aggressive assessment of the test device and there is no need to address the variable effect of anticoagulation therapy in each animal. In general, although representative drugs and dosages may be stated in this chapter, the investigator with direct responsibility for animal studies is well advised to consult an experienced veterinarian for selections and dosages of drugs, as practice may change over time and unforeseen complications may arise.

Canine

The history of the use of canines in experimental surgery is extensive. Early experimental surgery required an animal model that was inexpensive, readily available, and easily managed. The solution to this problem came in the form of mongrel dogs. Dogs could be obtained from pounds inexpensively and were often familiar with humans. Cardiopulmonary bypass, coronary artery bypass, and early valve studies were all developed primarily with the canine model. The evaluation of artificial heart valves began in the 1950s, using a canine model and valves created from materials such as polyurethane (Akutsu et al., 1974; Doumanian and Ellis, 1961). The canine model is suitable for testing both synthetic and biosynthetic vascular grafts used for coronary artery bypass. The canine model represents the gold standard for in vivo models of coronary artery bypass, and offers several advantages including: (1) a large historical database for comparison; (2) ease of cardiopulmonary bypass; and (3) the availability of autologous saphenous vein for grafting allows researchers to easily perform positive controls.

Interestingly, few studies involving PCI (percutaneous coronary intervention) for stent placement have been performed using this gold standard model (Schatz et al., 1987; Roubin et al., 1990). Because of the recent shift away from the canine as a model for chronic device evaluation, the current standard uses a swine model. Overall, the canine model has provided a long history of significant contributions to our understanding of cardiovascular physiology, and to the development and testing of cardiovascular biomaterials and devices. In more recent times, there has been a shift away from the canine model for many studies, because of public concerns and rising animal costs. Today, the emotional import of using canines for research has prohibitively increased their cost, and society no longer deems dogs appropriate for chronic studies. As a result, models using other large domestic animals have become widely used for ongoing biomaterials research.

Swine

Introduction

It is believed that the majority of the breeds of swine we now know are descended from the Eurasian wild boar (Sus scrofa). Archaeological evidence from the Middle East indicates domestication of the pig occurred as early as 9000 years ago, with some evidence for domestication even earlier in China. From here, the domestic pig spread across Asia, Europe, Africa, and ultimately North America (Towne and Wentworth, 1950; Mellen, 1952; Clutton-Brock, 1999a). Today, swine serve many purposes in society, ranging from food source and pets to biomedical research subjects. In this latter role, swine have proven useful during the past four decades in studying a variety of human ailments, including cardiovascular (Ramo et al., 1970; Cevallos et al., 1979), gastrointestinal (Kerzner et al., 1977; Leary and Lecce, 1978; Pinches et al., 1993), and hepatic diseases (Mersmann et al., 1972; Soini et al., 1992; Sielaff et al., 1997). Studies in swine have also provided extensive information in the areas of organ transplantation (Calne et al., 1974; Marino and De Luca, 1985; Grant et al., 1988; Al-Dossari et al., 1994; Granger et al., 1994).

Multiple authors have reported advantages of using swine in large animal models for biomedical research including, but not limited to, anatomic and physiologic similarities to humans, low cost, availability, and the ability of swine to produce large litters of hearty newborns (Stanton and Mersmann, 1986; Swindle, 1992; Tumbleson and Schook, 1996; Swindle, 2007). In addition, naturally occurring models of human disease (e.g., atherosclerosis) can be found in various strains of swine, making them ideal candidates for the study of these disease processes. Also helpful to investigators using swine is a large body of agricultural literature in the areas of swine nutrition, reproduction, and behavior that may have applications in biomedical research. For all these reasons, the use of swine has become increasingly popular in the biomedical research laboratory.

Comparative Anatomy and Physiology

Swine are the single readily-available species in which cardiovascular anatomy and physiology most closely resembles those in humans, likely because of a similar phylogenetic development that led to an omnivorous species with a cardiovascular system that has accommodated to a relative lack of exercise (McKenzie, 1996). The heart of an adult swine weighs 250–500 grams and comprises approximately 0.25% of the body weight (Ghoshal and Nanda, 1975), similar to that of humans. The coronary vasculature of a pig heart is nearly identical to that of humans in anatomic distribution, reactivity, and paucity of collateral flow (Hughes, 1986). The right and left coronary arteries are similar in size to each other. The left coronary artery supplies the greater part of the wall of the left ventricle and auricle, including the interventricular septum, by means of its circumflex and paraconal interventricular branches. The right coronary artery supplies the wall of the right ventricle and the auricle via its circumflex and subsinuosal branches (Ghoshal and Nanda, 1975). These similarities make swine ideal for studies of both ischemia/reperfusion and coronary stent technology.

There are certain cardiovascular anatomic differences between swine and humans that must be considered when using swine as investigational subjects. First, the left azygous vein drains directly into the right atrium in swine, compared to drainage into the brachiocephalic vein in humans (Ghoshal and Nanda, 1975). Second, there are only two arch vessels coming off the aorta in swine. The most proximal of these is the brachiocephalic trunk, which gives rise to the right subclavian and a common carotid trunk that bifurcates into the right and left carotid arteries. The second arch vessel is the left subclavian artery (Ghoshal and Nanda, 1975).

Electrophysiological parameters of pigs more closely resemble those of humans than any other non-primate animal. These parameters include similar P- and R-wave amplitudes, P–R intervals of 70–113 msec (longer in older animals), mean QRS duration of 39 msec, a Q–T interval of 148–257 (again longer in older animals), as well as ventriculoatrial (V–A) conduction when the right ventricular endocardium is stimulated faster than normal sinus rate (Hughes, 1986). These similarities make the pig a good model for studying pacemakers. Some investigators have found swine to be highly susceptible to ventricular arrhythmias, often requiring prophylactic pharmacologic protection (i.e., lidocaine, flecainide or bretylium). Alternatively, other investigators have exploited this ventricular instability to study “induced” tachyarrhythmias, and the pharmacologic agents and/or electrical interventions used in their management (Hughes, 1986).

Physiologically, swine have hemodynamic and metabolic values that are similar to those of humans (Tables II.3.7.1 and II.3.7.2). They also share similar pulmonary function parameters, such as respiratory rate and tidal volumes (Willette et al., 1996). Although they have lower levels of hemoglobin, circulating red cell volume, arterial oxygen saturation, and markedly lower venous oxygen saturations, they have similar platelet function and lipoprotein patterns. Other physiologic characteristics that may play a role in experimentation include a higher core body temperature, a contractile spleen that sequesters 20–25% of the total red cell mass, very fragile arteries and veins, a higher plasma pH, and a higher plasma bicarbonate level. Swine also have 50% more functional extracellular space than humans, and a slightly increased volume of total body water (Swindle et al., 1986; Hannon et al., 1990). However, individual swine test subjects tend to be more sensitive to anticoagulation therapy. Thus, if anticoagulation is utilized during the procedure, each animal will likely require a different dosage of anticoagulation, resulting in a series of individual anecdotes that are not easily summarized or generalized.

TABLE II.3.7.1 Hemodynamic Values of Species Used to Evaluate Cardiac and Vascular Bioprostheses

Values represent mean ± standard deviation.

Table created from: McKenzie, J. E. (1996). Swine as a model in cardiovascular research. In M. E. Tumbleson and L. B. Schook (Eds.), Advances in Swine in Biomedical Research. Plenum Press; New York, NY, pp. 7–17; Gross, D. R. (1994). Animal Models in Cardiovascular Research, 2nd edn. Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Kaneko, J. J., Harvey, J. W. & Bruss, M. L. (1997). Clinical Biochemistry of Domestic Animals, 5th edn. Academic Press: San Diego, CA; Fauci, A. S., Braunwald, E., Isselbacher, K. J., Wilson, J. D. & Martin, J. B. et al. (1998). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. McGraw-Hill: New York, NY.

TABLE II.3.7.2 Metabolic and Hematologic Values of Species Used to Evaluate Cardiac and Vascular Biomaterials

Values represent mean ± standard deviation.

Table created from: Hannon, J. P., Bossone, C. A. & Wade, C. E. (1990). Normal physiologic values for conscious pigs used in biomedical research. Laboratory Animal Science, 40(3), 293–298; McKenzie, J. E. (1996). Swine as a model in cardiovascular research. In: Advances in Swine in Biomedical Research. Plenum Press: New York, NY, pp. 7–17; Fauci, A. S., Braunwald, E., Isselbacher, K. J., Wilson, J. D. & Martin, J. B. et al. (1998). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. McGraw-Hill: New York, NY; Kaneko, J. J., Harvey, J. W. & Bruss, M. L. (1997). Clinical Biochemistry of Domestic Animals, 5th edn. Academic Press: San Diego, CA; Gross, D. R. (1994). Animal Models in Cardiovascular Research, 2nd edn. Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

Perioperative Care

Anesthesia

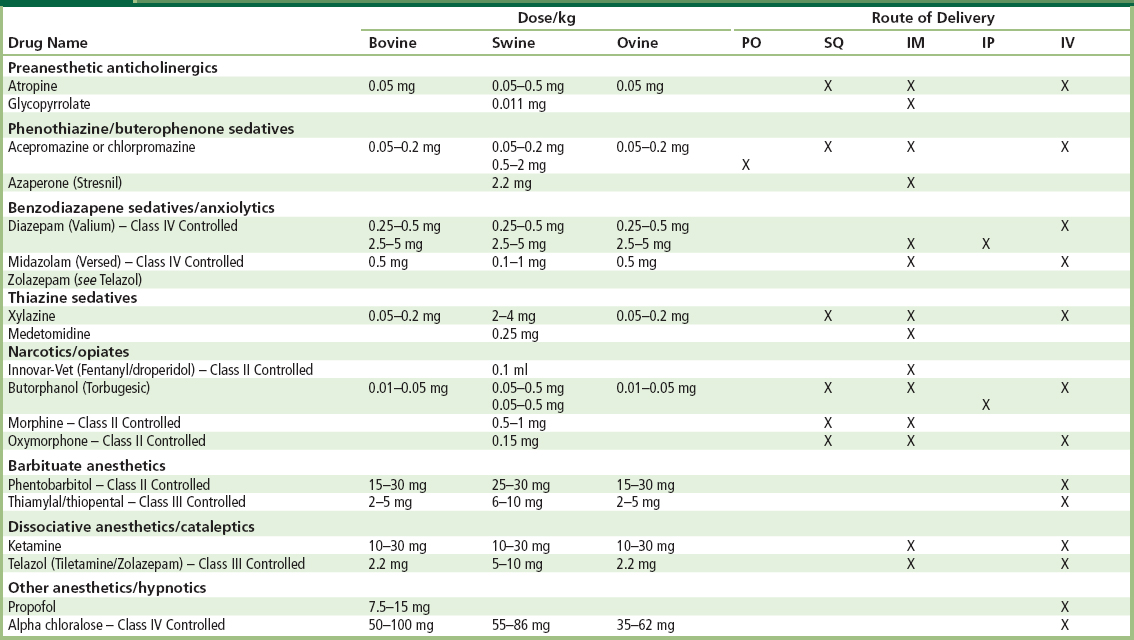

Swine should be fasted at least 12 hours prior to the induction of anesthesia, longer if one desires the large bowel to be empty prior to surgery. Unless gastric surgery is to be performed, the animals may be given water without restriction. It is common to administer an intramuscular (IM) pre-anesthetic agent followed by an intravenous (IV) anesthetic agent after IV access has been obtained. IM injections can safely be administered in the neck just behind the ear, in the triceps muscle of the forelimb or in the semimembranosus–semitendinosus muscles of the hindlimb. IV access is most commonly obtained in the lateral auricular veins (Riebold and Thurmon, 1985; Swindle and Smith, 1994; Swindle, 1994; Smith et al., 2008). The pre-anesthetic/anesthetic protocol used in this laboratory involves the administration of an IM injection of a combination drug (Telazole) consisting of a dissociative anesthetic and a tranquilizer (tiletamine and zolazepam) at a dose of 2–4 mg/kg for sedation. Following this, IV thiopental sodium (6–25 mg/kg) is administered if necessary. Endotracheal (ET) intubation follows and anesthesia is maintained via inhaled isoflurane (1–2 volume %). Commonly used anesthetics, doses, and routes of delivery are given in Table II.3.7.3.

TABLE II.3.7.3 Anesthetics and Sedatives Acceptable for Use in Species Used to Evaluate Cardiac and Vascular Biomaterials

PO, oral; SQ, subcutaneous; IM, intramuscular; IP, intraperitoneal; IV, intraveneous.

Table adapted from the University of Minnesota Animal Care and Use Manual 1997 reprint.

Analgesia

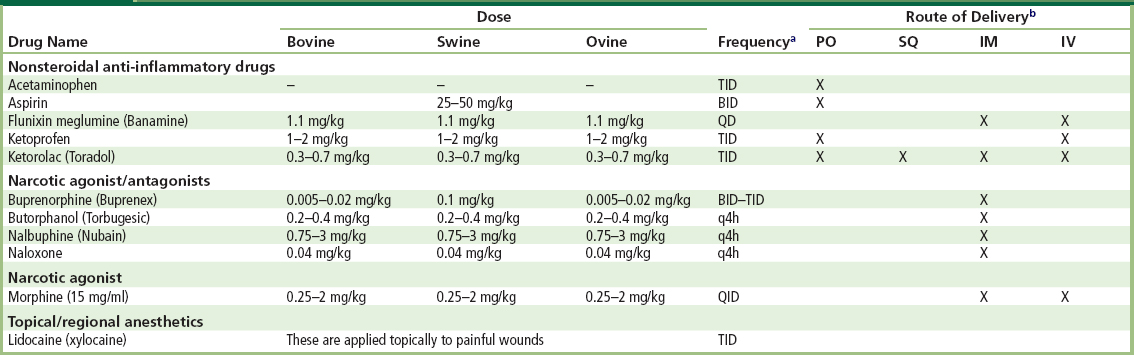

Postoperative analgesia is a very important component of any animal experiment. Appropriate use of postoperative analgesia involves rapid recognition of discomfort and appropriate therapy. When in pain or distress swine will demonstrate changes in social behavior, gait, posture, and a lack of bed-making. Most swine will become very reluctant to move when in pain and, if forced to move, will vocalize with even greater enthusiasm than they generally display (Gross, 1994). Buprenorphine is currently the analgesic of choice used in swine, effective when administered at 0.05–0.1 mg/kg every 8–12 hours (Swindle and Smith, 1994; Swindle, 1994). Standard narcotics such as morphine and fentanyl are effective pain relievers, but have a very short half-life in swine. Additional analgesic agents are listed in Table II.3.7.4.

TABLE II.3.7.4 Analgesics Commonly Used when Testing Biomaterials in Large Animal Models

Table adapted from the University of Minnesota Animal Care and Use Manual 1997 reprint.

aQD, once daily; BID, twice daily; TID, three times daily; QID, four times daily; q4h, every 4 hours.

bPO, oral; SQ, subcutaneous; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous.

Existing Models

Cardiac Devices

Orthotopic valve replacement in large animals is an important component of preclinical prosthetic valve assessment for the initial evaluation of surgical handling characteristics, hemodynamic performance, and valve-related pathology. Early investigators using swine for cardiovascular research described difficulties with venous access (Swan and Piermattei, 1971), anesthesia (Piermattei and Swan, 1970), cardiopulmonary bypass (Swan and Meagher, 1971), and several anatomic peculiarities (Swan and Piermattei, 1971). Subsequently, cardiovascular surgical procedures using swine have become technically feasible, and several investigators have conducted acute and chronic studies for the assessment of hemodynamic profiles of cardiac prostheses (Hasenkam et al., 1988a,b, 1989; Hazekamp et al., 1993). However, only a few long-term swine studies have been performed to examine the potential of prosthetic heart valve implants for thrombogenicity (Gross et al., 1997; Henneman et al., 1998; Grehan et al., 2000).

It has been reported that heart valve replacement in swine requires certain measures not needed with other species. These include the use of a crystalloid prime without plasma volume expanders (especially starch-based), prophylactic administration of pharmacological protection against ventricular arrhythmias, insurance of adequate hypothermic cardioprotection during the time of cross-clamp, administration of “shock” doses of corticosteroid just prior to reperfusion, and the use of inotropic support during bypass weaning (Gross et al., 1997). In our experience, (see later discussion) however, we have found some of these precautions unnecessary for the successful use of the pig in the evaluation of cardiac prostheses.

In our investigation, 22 swine underwent mitral valve replacement with no operative deaths. All animals were weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass without inotropic assistance. No cardioplegic protection was used, and only mild total body hypothermia was instituted. Pathologic analysis of valves explanted from animals surviving more than 30 days demonstrated extensive fibrous sheath formation leading to valve orifice obstruction and restriction of leaflet motion in a significant number of animals. The extensive fibrous sheath formation (and subsequent valvular dysfunction) represents a chronic tissue response observed in many species following mitral valve replacement. This chronic tissue response, however, was noted to have developed sooner in swine than in our previous studies involving prosthetic valve implantation into other species (i.e., sheep). Additionally, we did not find this model to be useful in predicting device-related thrombogenicity, as there were no clinical or pathologic differences observed among the valve designs studied (Grehan et al., 2000). The utility of swine in predicting the thrombogenic potential of cardiac valvular prostheses is therefore limited.

Improved biotechnology has brought left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) into the clinical arena as a bridge to transplantation therapy for patients with end-stage cardiac disease or those suffering from acute myocardial infarction (Frazier et al., 1992; Oz et al., 1997; Park et al., 2000). Clinical observations of patients who have received LVAD have revealed that these patients have a propensity for developing right ventricular dysfunction. To study this phenomenon, a model of iatrogenic congestive heart failure (CHF) using seven days of rapid pacing to induce cardiomyopathy has been developed in swine (Chow and Farrar, 1992). This model has been used to investigate the hemodynamics and septal positioning of the assist devices that may contribute to right ventricular dysfunction (Chow and Farrar, 1992; Hendry et al., 1994).

Vascular Devices

Initially, the pig was developed as a model to study solid organ transplantation. However, more recently its use has made an impact on the study of vascular disease. The pig is currently the species of choice for in vivo evaluation of vascular stents, restenosis biology, and balloon injury. The advantages of using swine include: (1) easy access to coronary arteries with present catheterization and angioplasty techniques; (2) coronary arteries of sufficient size for catheters used in adult humans; (3) balanced coronary circulation that is anatomically similar to humans; (4) spontaneous development of atherosclerosis; and (5) comparable coagulation and fibrinolytic systems and lipid metabolism to humans (Fritz et al., 1980; White et al., 1989; Karas et al., 1992; Willette et al., 1996).

Numerous in vitro studies indicate that the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems in swine closely resemble those of humans (Wilbourn et al., 1993; Karges et al., 1994; Reverdiau-Moalic et al., 1996; Gross, 1997), which would suggest that this may be the ideal species for the preclinical evaluation of the thrombogenic potential of a prosthetic device. In vivo studies specifically looking at the thrombogenicity of implantable devices, both cardiac and noncardiac, have already been performed in swine (Rodgers et al., 1990; Walpoth et al., 1993; Scott et al., 1995). Previous in vivo studies of artificial valves identified a relationship between postoperative thrombus formation and bacteremia. Other significant factors impacting survival include a combination of preoperative antibiotics, postoperative anticoagulation, short bypass times, and aseptic blood sampling techniques (Bianco et al., 1986). Table II.3.7.5 outlines various antibiotics used in cardiovascular in vivo studies and their suggested dosing regimens.

TABLE II.3.7.5 Antibiotics Acceptable for Use in Large Animal Models

Table adapted from the University of Minnesota Animal Care and Use Manual 1997 reprint.

aQD, once daily; BID, twice daily; TID, three times daily; QID, four times daily; q48h, every 48 hours.

bPO, oral; SQ, subcutaneous; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous.

Similar investigations have shown that stent thrombosis may occur early in swine in vivo models (within 6 hours of implantation), suggesting that if a pig survives the first 12 hours (coronary stent remains patent), it is highly likely that it will not suffer a stent occlusion later (Schwartz and Holmes, 1994). Observations of such rapid restenosis led Schwartz and Holmes to suggest that the pig should be used as an accelerated thrombotic model capable of predicting stent thrombosis within hours of implant (Schwartz and Holmes, 1994). Stenting or balloon inflation in the swine model leads to intimal smooth muscle cell proliferation that closely resembles the cell size, density, and histopathological appearance of that seen in human restenosis (Karas et al., 1992; Bonan et al., 1996; Willette et al., 1996). Additionally, as in humans, there is a predictable relationship between vascular injury and restenosis (i.e., more neointima is formed with deeper lesions) (Willette et al., 1996; Jordan et al., 1998).

Although investigation of stents and balloon injury has mainly been done using coronary arteries (Karas et al., 1992; Bonan et al., 1996; Willette et al., 1996), studies using other arteries, such as the iliacs, have also been performed (White et al., 1989). Swine have also been used to study the feasibility of percutaneous repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA). Jordan et al. (1998) developed an AAA model using rectus abdominus fascia, and demonstrated prolonged survival in stented AAA in comparison to unstented controls. Unfortunately, this AAA model did not accurately mimic aneurysms seen in humans, as the AAA created was saccular and did not reproduce the geometric configuration or collateral circulation and back bleeding observed in human disease (Jordan et al., 1998). Whitbread et al. (1996) created an AAA model in swine by interposing fusiform segments of glutaraldehyde-treated bovine internal jugular vein into the infrarenal aorta. This resulted in a pulsatile, nonthrombogenic AAA that approximates human dimensions (20 mm) and geometry (fusiform) (Whitbread et al., 1996). Both AAA models have been used to develop stents and stent placement technology with the goal of reducing the pulsatility and diameter of the aneurysm while maintaining location of the stent without occluding nearby vessels.

Swine models have become useful and popular to study biomaterials and the devices manufactured from these materials. Anatomic and physiologic similarities to humans have made swine the species of choice to study many cardiac and vascular prostheses, especially in acute studies looking at hemodynamic profiles of different devices. However, difficulties with husbandry and species temperament, and a rapid rate of somatic growth, have made swine less desirable as models for the chronic evaluation of devices in our experience.

Bovine

Introduction

There are many species of cattle which are generally bred as livestock for meat and dairy production, as well as draft animals. Cattle have long been domesticated since Neolithic times as a distinct species as the genus Bos, and are often hybridized between closely related species. Cattle are raised in herds and graze in large areas of grassland or in feedlots. Cattle are of moderate intelligence and vocalize occasionally with a characteristic lowing sound, bawling or bellowing. The animals are usually mild mannered, slow moving, usually cooperative, and can be controlled behaviorally by education or with barriers.

Aside from antibody production, the cow is not often used in biomedical research, because of their size and husbandry needs. The cow’s ability to produce milk is a potential source for genetically engineered proteins; that, however, remains ethically controversial. The calf has been used in cardiovascular research for both ventricular assist device testing and valve implantation. Ventricular assist devices are generally too large to be tested with smaller animals such as the dog, and pigs are not cooperative enough.

Comparative Anatomy and Physiology

Interestingly, the bovine genome has been recently mapped with about 80% of the genome similar to that of humans, despite obvious phenotypic differences. Cattle are ungulates and ruminants with a four-compartment stomach for digestion. Microbes in the rumen decompose cellulose into carbohydrates and fatty acids, and synthesize amino acids from urea and ammonia. The gestation period for a cow is nine months and a newborn calf weighs about 25–45 kg.

The bovine heart comprises 0.4%–0.5% of the body weight, which in the adult weighs about 2.5 kg. Aside from the normal mammalian structure of the heart, the bovine heart differs in that the great cardiac vein drains directly into the azygos. A semilunar valve (Thebesian valve) at the margin of the azygos and right atrium allows for unidirectional coronary venous flow. As the calf grows older, two bones called the ossa cordis develop in the fibrous aortic ring at the attachments of the right and left semilunar cusps. The bovine aortic arch consists of a common trunk that symmetrically branches into the right and left brachiocephalic arteries, supplying the head and upper extremities.

The bovine ventricles lend a conical appearance to the apex, with both an anterior and posterior interventricular groove, as well as an intermediate lateral groove for vessels. The left auricle is larger than the right atrial appendage. The left coronary artery is also larger than the right. The left coronary artery divides into the paraconal interventricular and circumflex branches. The circumflex artery courses in the coronary groove under the cardiac vein, and gives off a prominent subsinusoal interventicular branch which descends to the apex. The interventricular artery descends anteriorly to anastomose with a branch of the subsinuosal. As mentioned above, the right coronary artery is smaller than the left and lies in the right coronary groove covered by the right atrial appendage and terminates in small branches that anastomose with the subsinuosal interventricular artery.

Rheologic conditions are altered with different velocities of blood flow and blood stasis in animals following implantation of cardiac devices. As one of the fundamental homeostatic mechanisms of mammalian biology, the blood coagulation system establishes a delicate balance between the procoagulant and anticoagulant functions of blood and the vessel wall, thereby guarding against excesses in either direction and normally preventing unwanted hemorrhage or thrombosis. Despite all efforts to achieve effective anticoagulation, the risk of thromboembolic events is still approximately 30% in humans. The main reason for clot formation is the contact between blood components and foreign surfaces. System components induce a cascade of interacting proteases, accelerating steps that provide amplification, a variety of balanced feedback controls, and, most importantly, tightly regulated activation. Unfortunately, the range of biocompatibility assays for the evaluation of blood contacting materials is limited using the bovine model. Recent reports to quantify bovine circulating activated platelets have been developed using the monoclonal antibodies to BAQ125, GC5, and annexin V (Baker et al., 1998; Snyder et al., 2002). Additional assays to quantifying bovine platelets which have human analogs are now possible using platelet-expressing CD62P and CD63. CD62P (p-selectin, platelet activation dependent granule external membrane protein (PADGEM), granule membrane protein-140 (GMP-140)) and CD63 (lysosomal-membrane-associated glycoprotein 3 (LAMP-3), granulophysin, LIMP, PLTGP40, gp55) are both expressed on the surface of platelets following activation and degranulation (Snyder et al., 2007).

Perioperative Care

Anesthesia

Calves should be fasted for 12–18 hours preoperatively to decrease the likelihood of regurgitation during the induction of anesthesia and ET intubation. Typically, a sedative is administered IM to allow easy and safe placement of IV catheters for controlled administration of medication. Several sedatives are useful in the pre- and postoperative periods to aid in animal handling and for performing minor procedures (Table II.3.7.3). A common protocol uses ketamine, 10 mg/kg IM as a pre-anesthetic sedative. Anticholinergics or parasympatholytics, especially atropine, have been used on induction of anesthesia to decrease salivary and respiratory tract secretions. Table II.3.7.3 lists the recommended dosing of such agents. Once the sedative has taken effect, IV catheters can be easily introduced into the external jugular, cephalic or saphenous veins. Following placement of a secure IV catheter and the administration of short-acting relaxing agents (Table II.3.7.3), ET intubation can be safely performed using standard cuffed ET tubes 10–16 mm in internal diameter. Placement of the orogastric tube typically follows ET intubation. Orogastric intubation is especially important if preoperative fasting does not occur. The endotracheal tube can then be connected to a conventional anesthetic ventilator to maintain a deep plane of anesthesia. Preferred inhalation anesthetics for bovine are halothane (1.5–2.5%) or isoflurane (1.5–3%).

Analgesia

Calves are stoic and it is uncommon for them to vocalize when they are in pain. A reluctance to move, favoring the procedural site, excessive licking or scratching of the site, kicking, lack of appetite, and/or a depressed attitude are behaviors that may indicate a calf is experiencing pain. Scheduled medication administration and periodic evaluation of behavior can help to ensure adequate pain relief. Commonly used analgesics include narcotics administered via a subcutaneous, IV or epidural route. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents can be used in divided doses for additional analgesia. Table II.3.7.4 lists recommended dosing of additional analgesics.

Existing Models

Cardiac Devices

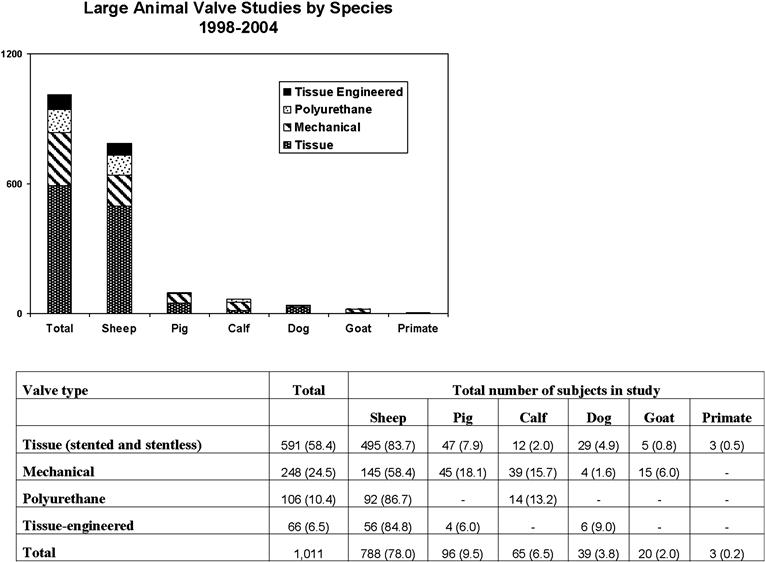

The calf model was first used extensively in cardiovascular research in the 1980s for the purpose of calcification studies (Schoen et al., 1985; Dewanjee et al., 1986a,b). A review of the current literature reflects diminished utilization of this model, accounting for only 6.5% reported animal studies, primarily because it shares many of the limitations noted with the pig model Figure II.3.7.3. A major limitation for chronic survival studies is the rapid somatic growth of the calf, contributing to both anatomic and hemodynamic alterations that undermine the validity of long-term follow-up studies. The rapid somatic growth in the calf is associated with dramatic elevation in cardiac output, well above the maximum observed in humans. In fact, if the bovine model were used for a standard six-month trial, the cardiac output (CO) would be expected to be nearly three times greater than that of the adult human at the end of six months.

FIGURE II.3.7.3 Reported preclinical in vivo assessment by species and valve type. Values in parentheses are percentage of total studies.

(Adapted from Gallegos et al., 2005. Used with permission.)

Anatomically, the calf valve annulus is larger than that of humans (Tables II.3.7.1 and II.3.7.6) (Gallegos et al., 2005). Therefore, implantation of a prosthetic valve of a size that would be typically utilized in an adult human would result in patient prosthesis mismatch if placed in the calf aortic position. The result of patient prosthesis mismatch produces outflow obstruction, with valves sized for clinical relevance, and any additional growth may contribute to paravalvular leak development, as was observed in the pig model (Linden et al., 2003). It is well-known that a valve’s effective orifice area (EOA) significantly impacts on the incidence of heart failure symptoms, adverse cardiac events, preoperative mortality, LV impairment, and is associated with short- and long-term mortality (Pibarot et al., 1998; Pibarot and Dumesnil, 2000, 2001; Blais et al., 2003). Indeed, this was actually reported in a bovine valve study whereby a majority of calves were actually in heart failure, given that the mean CO was only 12 ± 6 l/min with the study valve in place, when the expected normal value would be in the range of 18–20 l/min, based on animal weight and study duration (see Table II.3.7.6). Unfortunately, the calf model is not an ideal animal for testing prosthetic valves in a preclinical setting, because of the growth that causes an inherent patient prosthesis mismatch.

TABLE II.3.7.6 Important Cardiac Parameters for Cardiac Valve Implantation Studies

Values represent mean ± standard deviation.

Table adapted from Gallegos et al. 2005. Used with permission.

On the other hand, the bovine model is the most commonly used model for ventricular assist devices (Litwak et al., 2008). Calves are used in preclinical studies to provide information about the function, biocompatibility, and efficacy of ventricular assist devices (VAD). The VAD is a blood pump system designed to palliate severe congestive heart failure, and is a system composed of inflow and outflow cannnulae, connectors, and controllers. The blood contacting surfaces are procoagulant and activate blood clotting, so every attempt is made in the preclinical setting to minimize adverse events. Numerous VAD systems have been developed and implanted in calves with a variety of adverse events, such as thrombus, obstructions or kinks, mechanical, electrical or software failures that can occur within any component of the LVAD.

Clearly, valve replacement in the calf model is representative of the patient prosthesis mismatch condition, rather than an ideal in vivo model for replacement human valves. Choice of the animal model to study the replacement valve’s hemodynamic characteristics should ideally reduce or eliminate confounding factors, such as patient prosthesis mismatch. Therefore, the calf model is not an ideal animal for testing prosthetic valves in a preclinical setting, because of the growth that causes an inherent patient prosthesis mismatch, as mismatch is strongly predictive of congestive heart failure following aortic valve replacement as well as re-operation (Ruel et al., 2004a,b). Thus, bovine models are best suited for acute studies in which somatic growth would not bias results or specifically to study the effect of patient–prosthesis mismatch itself.

Vascular Devices

There are no widely-used bovine in vivo models of vascular devices, so we will not discuss them further.

Ovine

Introduction

As a gentle, docile animal, sheep were among the first species to be domesticated, approximately 10,000 years ago as evidenced by pictures and statuettes depicting sheep in the Middle Eastern region. They remain popular to this day as a source of both food and goods. The prevailing theory for the origin of the domestic sheep is that they originated from the wild sheep known as mouflon (Ovis musimon). Currently, mouflon can be found in two separate geographic locales: Asiatic mouflon in Asia Minor and southern Iran; and European mouflon on the islands of Sardinia and Corsica (Clutton-Brock, 1999b). The rapid expansion of agriculture and human consumption has been both the cause and effect of routine crossbreeding of sheep. Currently more than 200 different breeds exist worldwide. Common breeds used in surgical research include smaller breeds commercially used for meat, such as the Hampshire and Dorset varieties, or the larger sheep, often used for wool commercially, such as the Merino and Rambouillet breeds.

Comparative Anatomy and Physiology

Specific organ differences between humans and sheep are notable (e.g., ruminant gut anatomy). However, in many instances the similarity in organ size of adult sheep to their human counterparts allows adequate approximation for the study of mechanical and bioprosthetic biomaterials and devices prior to human implantation. The ovine thorax has an exaggerated conical shape with a narrow spax (cranial aperture or thoracic inlet) and a caudal thoracic aperture that is six times wider. Cardiopulmonary anatomy is generally similar to that of humans, making sheep ideal models for cardiac research; however, a few anatomic differences require consideration (Hecker, 1974), for example, the single brachiocephalic artery arising from the aortic arch. In addition, tracheal anatomy varies slightly from humans, with the cranial lobe of the right lung arising directly from the trachea rather than the right mainstem bronchus. This variation can pose a difficulty during endotracheal intubation on induction of anesthesia, and can result in nonventilation of a significant pulmonary segment (Carroll and Hartsfield, 1996).

Physiologic parameters (heart rate, blood pressure, cardiac index, and intracardiac pressures) have been established through numerous studies in both anesthetized and conscious sheep, including the percentage of blood flow to each major organ system (Matalon et al., 1982; Nesarajah et al., 1983; Newman et al., 1983). In most instances, the hemodynamic and metabolic values are similar to those of other large mammals, including humans (Tables II.3.7.1 and II.3.7.2).

In cardiovascular bioprosthesis studies, similarities between human and animal hematologic systems are important. Although there are differing blood groups, typing is unnecessary, as transfusion has never been necessary in our experience of over 30 years of working with sheep. There have been occurrences of a reaction, most often a dermatological response, which is easily treated with diphenhydramine. A comparison of the coagulation parameters and hematologic profiles between sheep and humans reveal some differences, which become important in assessing the thrombogenicity of implanted cardiovascular prostheses. Notably, sheep possess decreased fibrinolytic activity and increased platelet number and adhesiveness (Gajewski and Povar, 1971; Tillman et al., 1981; Karges et al., 1994).

Perioperative Care

Anesthesia

Sheep should be fasted preoperatively to decrease the likelihood of regurgitation on induction of anesthesia and ET intubation. The reticulum, the most proximal rumen, has no sphincter mechanism at its oral end and often needs intubation and suction decompression to prevent regurgitation and aspiration (Holmberg and Olsen, 1987; Carroll and Hartsfield, 1996). Orogastric intubation is especially important if preoperative fasting does not occur. Typically, a sedative is administered IM to allow easy and safe placement of IV catheters for controlled administration of medication. Several sedatives are useful in the pre- and postoperative periods to aid in animal handling, and for performing minor procedures as shown in Table II.3.7.3. Large named veins such as the internal or external jugular or femoral veins can be used to secure IV access for fluid administration and frequent blood draws. Specialized catheters such as pulmonary artery catheters or long-term tunneled venous catheters (Hickman) may also be placed in these easily accessible, large veins (Tobin and Hunt, 1996). Following placement of a secure IV catheter and the administration of short-acting relaxing agents, ET intubation can be safely accomplished using standard cuffed ET tubes 5–10 mm in internal diameter. Anticholinergics or parasympatholytics, especially atropine, have been used on induction of anesthesia to decrease salivary and respiratory tract secretions. Use of these agents, however, is controversial in ruminants such as sheep, goats, and cattle because they inhibit gastrointestinal smooth muscle activity, which can cause rumen stasis in sheep (Carroll and Hartsfield, 1996). Table II.3.7.3 lists the recommended dosing of anesthetic agents.

Analgesia

Scheduled medication administration and periodic evaluation of behavior can help to ensure adequate pain relief. Sheep should be assessed for changes from their preoperative temperament. Sheep tend to react stoically to pain, and their refusal to move can often indicate even minor discomfort (Carroll and Hartsfield, 1996). Other common clinical signs of postprocedural pain include tachycardia, tachypnea, grunting, grinding teeth, decreased appetite, vocalization on movement, and guarding of the operative site. Commonly used analgesics include narcotics administered via a subcutaneous, IV or epidural route. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) can be used in divided doses for additional analgesia. Table II.3.7.4 contains recommended dosing of analgesics.

Existing Models

Cardiac Devices

Because of the similar anatomic and physiologic characteristics of sheep and humans discussed earlier, sheep are often used in cardiovascular biomaterial research, and several models have been developed for studying compatibility and function of biomaterials. A total artificial heart model was developed in sheep at the University of Utah’s Artificial Heart Laboratory in the 1980s (Holmberg and Olsen, 1987). Other studies examined the potential use of synthetic or xenograft pericardial substitutes to reduce adhesion formation following coronary artery bypass or valve replacement (Gabbay et al., 1989; Bunton et al., 1990).

Many investigators have employed sheep in the preclinical testing of mechanical valves in both the aortic and mitral positions (Barak et al., 1989; Vallana et al., 1992; Irwin et al., 1993; Cremer et al., 1995; Bhuvaneshwar et al., 1996; Okazaki et al., 1996). Our experience discovered that the use of juvenile sheep (younger than 20 weeks) results in an excellent long-term model for mechanical prosthetic valve evaluation. Careful standardization to prevent infectious complications, short cardiopulmonary bypass time, whole sheep blood transfusion to minimize anemia, and rumen decompression with an orogastric tube to prevent vena caval compression were found to be useful in the successful implementation of this model (Irwin et al., 1993).

Acute and chronic models of stented bioprosthetic valves are well established through several studies in both the mitral and aortic position in sheep (Gott et al., 1992; Liao et al., 1993; Bianco et al., 1996; Vyavahare et al., 1997; Northrup et al., 1998; Ouyang et al., 1998; Salerno et al., 1998; Spyt et al., 1998). Sheep grow at a rate that is comparable to human growth, which allows for comparative analysis. In contrast, larger ruminants such as cattle and large varieties of swine experience rapid and prolonged growth until reaching a large adult size (Bianco et al., 1996; Grehan et al., 2000; Gallegos et al., 2005). Such rapid growth can cause difficulties in size matching between prosthetic valves and the native valve annulus, resulting in paravalvular leaks and functional valve stenosis (Braunwald and Bonchek, 1967; Gallo and Frater, 1983; Spyt et al., 1998). Premature leaflet calcification can occur in stented bioprosthetic valves because of abnormal mechanical loading characteristics. This is most consistently reproduced in juvenile sheep (younger than 6 months). We and others currently employ a model in sheep younger than 20 weeks to study both the dynamic environment related to growth of the sheep and the chronic effect of calcification in stented porcine bioprosthetic valves in the aortic position (Gott et al., 1992; Liao et al., 1993; Bianco et al., 1996; Ouyang et al., 1998).

Sheep also provide an important model for the study of low-profile stentless aortic valves (David et al., 1988; Brown et al., 1991; Hazekamp et al., 1993; Schoen et al., 1994; Salerno et al., 1998). In this regard we found that, with careful surgical technique including a two-thirds transverse aortotomy for superior exposure and meticulous avoidance of coronary ostial obstruction by the scalloped valve edges, sheep provide an excellent in vivo preclinical model to test these aortic valves (Salerno et al., 1998).

In addition to the subcoronary implantation of these stentless devices, this laboratory has also developed a juvenile sheep model of aortic root replacement to allow for the preclinical evaluation of new or modified stentless devices using implantation techniques that parallel those seen in clinical practice. Again, careful attention to surgical technique proved to be very important in the success of this model, including creation of very generous-sized coronary buttons, inclusion of a posterior “rim” of native aorta in the proximal anastamosis, and the creation of a tension-free distal anastamosis by removing little if any native aorta (Grehan et al., 2001).

Vascular Devices

In addition to cardiac devices, researchers have studied the interface between blood and several biomaterial surfaces in the evaluation of biosynthetic vascular grafts placed in sheep. Several authors have noted the reduction in thrombogenicity provided by endothelial seeding of small-diameter synthetic vascular grafts constructed of expanded PTFE or woven Dacron® prior to placement in sheep (James et al., 1992; Taylor et al., 1995; Dunn et al., 1996; Poole-Warren et al., 1996; Jensen et al., 1997). Placement of vascular grafts composed of several engineered surface textures into sheep has also been performed in order to assess characteristics of the pseudointima layer (Fujisawa et al., 1999). Additionally, the important problem of intimal hyperplasia in the venous anastomosis of high-flow arteriovenous fistulas has recently been evaluated in a sheep model (Kohler and Kirkman, 1999).

Recent progress in the development of large-vessel endovascular stents has occurred in part due to research with specific vascular disease models in adult sheep, and has been increased by continued development of minimally invasive techniques. As in graft studies, there is significant interest in both the short- and long-term patency of endovascular stents. Stent incorporation into native tissue and the role of foreign-body reaction in normal arterial systems with respect to thrombogenicity and intimal hyperplasia has been evaluated in sheep aortic and iliac arteries (Rousseau et al., 1987; Neville et al., 1994; Schurmann et al., 1998; White et al., 1998). Current efforts have been directed at determining the role of endovascular stenting in the prevention of rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms, and the prevention of complications such as spinal cord ischemia through the use of these stents (Boudghene et al., 1998; Beygui et al., 1999).

Current cardiovascular research has embraced the humane use of sheep for the testing of a variety of cardiac and vascular devices composed of many different biomaterials. In all of these investigations, sheep have proved a useful and reliable model, as evidenced by this laboratory’s continued success using both juvenile and adult sheep for a variety of investigations. Figure II.3.7.3 depicts the relative use of various large animals for preclinical assessment of valves, with a reported 78% of studies using an in vivo sheep model. Current research indicates a trend towards an even broader application of emerging endovascular technologies. For many reasons, including their anatomic and physiologic similarities to humans, and a mild temperament that facilitates handling, the benefits of using sheep in preclinical studies continue to outweigh the use of other large animals in future investigations into biomaterials testing and development.

Testing Hierarchies

Conventionally-Placed Devices

Conventional coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) continues to be one of the mainstays of cardiovascular surgery (Wilson and Ferguson, 1995). Coronary artery disease remains the leading cause of death of people in developed countries, and an average of 800,000 CABG operations take place annually (Caparrelli et al., 2009). This requires the harvesting of one or more peripheral veins to reroute coronary vasculature and circumvent around an occlusion within the lumen of an artery while the patient is on cardiopulmonary bypass (Wilson and Ferguson, 1995). There are known risks for patients undergoing this surgical procedure, but the procedure itself is somewhat standardized and a common practice for surgeons. Similarly, the development and surgical implant of prosthetic valves dates back to the mid-20th century, and has proven to be another one of the greatest successes in surgery. Surgical valve replacement is well-established, and approximately 200,000 aortic valve replacements are performed annually worldwide (Fann et al., 2008). Advances in cardiopulmonary bypass, improved hemodynamic monitoring and perioperative care, and structural and hemodynamic improvements in prosthetic valves have aided in this success. Valve replacement surgery is now considered to have low operative mortality and constantly improving long-term survival rates (Fann et al., 2008; Christofferson et al., 2009). Its only limiting factor is the risk of conventional surgery on a patient with multiple comorbidities, a risk that obviously directly applies to patients undergoing CABG as well.

Percutaneously-Placed Devices