Chapter II.4.5

Pathological Calcification of Biomaterials

Introduction

Formation of nodular deposits of calcium phosphate or other calcium-containing compounds may occur on biomaterials and prosthetic devices used in the circulatory system and at other sites. This process, known as calcification or mineralization, has been encountered in association with both synthetic and biologically derived biomaterials in diverse clinical and experimental settings, including chemically-treated tissue (bioprosthetic) and homograft cardiac valve substitutes (Mitchell et al., 1998; Schoen and Levy, 1999, 2005), blood pumps used as cardiac assist devices (Schoen and Edwards, 2001), breast implants (Peters et al., 1998; Legrand et al., 2005), intrauterine contraceptive devices (Patai et al., 1998), urological stents (Vanderbrink et al., 2008), intraocular lenses (Neuhann et al., 2008; Nakanome et al., 2008; Rimmer et al., 2010), and scleral buckling materials (Brockhurst et al., 1993; Yu et al., 2005). Vascular access grafts for hemodialysis and synthetic vascular replacements composed of Dacron® or expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (e-PTFE) also calcify in some patients (Tomizawa et al., 1998; Schlieper et al., 2008). Calcification can lead to important clinical complications, such as stiffening and/or tearing of tissue heart valve substitutes, encrustation with blockage of a urinary stent or clouding of intraocular lenses (Table II.4.5.1).

TABLE II.4.5.1 Representative Prostheses and Devices with Clinical Consequences Due to Biomaterials Calcification

| Configuration | Biomaterial | Clinical Consequence |

| Cardiac valve prostheses | Glutaraldehyde-pretreated porcine aortic valve or bovine pericardium, and allograft aortic/pulmonary valves | Valve obstruction or incompetency |

| Cardiac ventricular assist bladders | Polyurethane | Dysfunction by stiffening or cracking |

| Vascular grafts | Dacron® grafts and aortic allografts | Graft obstruction or stiffening |

| Soft contact lens | Hydrogels | Opacification |

| Intrauterine contraceptive devices | Silicone rubber, polyurethane or copper | Birth control failure by dysfunction or expulsion |

| Urinary prostheses | Silicone rubber or polyurethane | Incontinence and/or infection |

Deposition of mineral salts of calcium (as calcium phosphates, especially calcium hydroxyapatite) occurs normally in bones and teeth, and is a critical determinant of their strength (called physiologic mineralization). Mineralization of skeletal tissues is both controlled and restricted to specific anatomic sites. The mature mineral phase of bone is a poorly crystalline calcium phosphate known as calcium hydroxyapatite, which has the chemical formula Ca10(PO4)6(HO)2. Mineralization of some implant biomaterials is desirable for proper function, e.g., osteoinductive materials used for orthopedic or dental applications (Habibovic and de Groot, 2007), and materials used to engineer skeletal and dental tissues (Kretlow and Mikos, 2007; Bueno and Glowacki, 2009). However, severe consequences can occur if mineralization occurs in regions that do not normally calcify (pathologic or ectopic mineralization) (Kirsch, 2008).

Since the biomaterials used in medical devices outside of the musculoskeletal and dental systems are not intended to calcify, calcification of these biomaterials is pathologic. The mature mineral phase of biomaterial-related and other forms of pathologic calcifications is a poorly crystalline calcium phosphate that closely resembles the calcium hydroxyapatite present in bones and teeth. Indeed, as we will see later, biomaterials-related calcification shares many features with other conditions of pathologic calcification and physiologic mineralization. Pathologic calcification of natural structures is also a common feature of important disease processes; for example, in native arteries and heart valves, calcification occurs as an important feature of the serious diseases atherosclerosis and calcific aortic stenosis, respectively (Mitchell and Schoen, 2010; Schoen and Mitchell, 2010).

Pathologic calcification is further classified as either dystrophic or metastatic, depending on its setting (Kumar et al., 2010). In dystrophic calcification the deposition of calcium salts (usually calcium phosphates) occurs in damaged or diseased tissues or related to biomaterials; moreover, dystrophic calcification usually occurs in the setting of normal systemic calcium metabolism (generally defined by a normal product of the serum levels of calcium and phosphorus). In contrast, metastatic calcification comprises the deposition of calcium salts in otherwise normal tissues in individuals who have deranged mineral metabolism, usually with markedly elevated blood calcium or phosphorus levels. Conditions favoring dystrophic and metastatic calcification can act synergistically. Thus, the rate and extent of dystrophic mineralization within abnormal tissues are accelerated when calcium and/or phosphorus serum levels are high, for example, in kidney failure or calcium supplementation (Umana et al., 2003; Peacock, 2010), and in osteoporosis (Hofbauer et al., 2007; Hjortnaes et al., 2010). Moreover, the ability to form physiologic mineral (e.g., in bone) is regulated through adjustment of enhancing and inhibiting substances, many of which circulate in the blood (Weissen-Planz et al., 2008). In young individuals (especially into early adulthood) the balance appropriately favors bone formation; moreover, the biochemical environment that favors physiologic bone formation in children also promotes calcification of biomaterials (Bass and Chan, 2006; Peacock, 2010).

The cells and extracellular matrix of dead tissues are the principal sites of pathologic calcification. Calcification of an implant biomaterial can occur within the tissue (intrinsic calcification) or at the surface, usually associated with attached cells and proteins (extrinsic calcification) or in the implant fibrous capsule. An important instance of extrinsic calcification is that associated with prosthetic valve infection (prosthetic valve endocarditis) or thrombi.

The Spectrum of Pathologic Biomaterials and Medical Device Calcification

Tissue Heart Valves

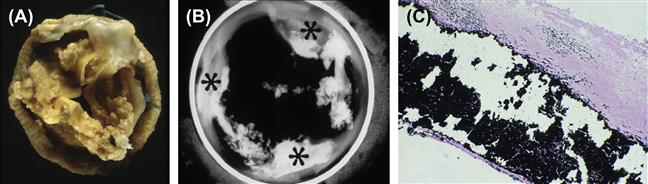

Calcific degeneration of glutaraldehyde-pretreated porcine bioprosthetic and bovine pericardial heart valves (Figure II.4.5.1) is a clinically significant and well-characterized dysfunction of a medical device due to biomaterials calcification (Schoen and Levy, 1999, 2005). The predominant pathologic process is intrinsic calcification of the valve cusps, largely initiated in the deep cells and the tissue from which the valve was fabricated and often involving collagen. Calcification leads to valve failure most commonly by causing cuspal tears, less frequently by cuspal stiffening, and rarely by inducing distant emboli. Overall, approximately half of porcine bioprostheses fail within 12–15 years. Calcification is more rapid and aggressive in the young; to exemplify, the rate of failure of bioprostheses is approximately 10% in 10 years in elderly recipients, but is nearly uniform in less than four years in most adolescent and preadolescent children (Chan et al., 2006).

Calcific degeneration of glutaraldehyde-pretreated porcine bioprosthetic and bovine pericardial heart valves (Figure II.4.5.1) is a clinically significant and well-characterized dysfunction of a medical device due to biomaterials calcification (Schoen and Levy, 1999, 2005). The predominant pathologic process is intrinsic calcification of the valve cusps, largely initiated in the deep cells and the tissue from which the valve was fabricated and often involving collagen. Calcification leads to valve failure most commonly by causing cuspal tears, less frequently by cuspal stiffening, and rarely by inducing distant emboli. Overall, approximately half of porcine bioprostheses fail within 12–15 years.

FIGURE II.4.5.1 Calcification of a pericardial bioprosthetic heart valve, implanted in a person for many years. (A) gross photograph, demonstrating marked thickening of cusps by nodular calcific deposits; (B) radiograph of another long-term valve, demonstrating predominant deposits at commissures; (C) photomicrograph demonstrating calcific nodule deeply embedded within cuspal tissue; von Kossa stain (calcium phosphates black) 100×.

In some young individuals with congenital cardiac defects or acquired aortic valve disease, human allograft/homograft aortic (or pulmonary) valves surrounded by a sleeve of aorta (or pulmonary artery) are used. Allograft valves are valves removed from a person who has died and transplanted to another individual; the tissue is usually cryopreserved, but not chemically cross-linked. Allograft vascular segments (without a valve) can be used to replace a large blood vessel. Allograft vascular tissue, whether containing an aortic valve or nonvalved, can undergo severe calcification, particularly in the wall; calcification can lead to allograft valve dysfunction or deterioration (Mitchell et al., 1998).

Polymeric Heart Valves and Bladders in Blood Pumps

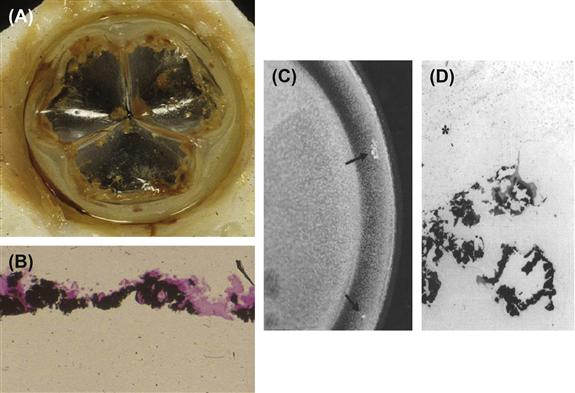

Calcification has also complicated the use of heart valves and artificial mitral valve chordae tendineae composed of polymers (e.g., polyurethane) (Fukunaga et al., 2010; Hilbert et al., 1987; Schoen et al., 1992a; Schoen and Levy, 1999; Wang et al., 2010) and the flexing bladder surfaces of blood pumps used as ventricular assist systems or total artificial hearts (Schoen and Edwards, 2001) (Figure II.4.5.2). Massive deposition of mineral leading to failure has been noted in experimental animals, but a lesser degree of calcification has been encountered following extended human implantation. Mineral deposits can result in deterioration of pump or valve performance through loss of bladder pliability or the initiation of tears. Blood pump calcification, regardless of the type of polyurethane used, generally predominates along the flexing margins of the diaphragm, emphasizing the important potentiating role of mechanical factors in this system (Coleman et al., 1981; Harasaki et al., 1987; Kantrowitz et al., 1995).

FIGURE II.4.5.2 Calcification of an experimental polymeric (polyurethane) heart valve. (A) gross photograph of valve; (B) photomicrograph calcified material at surface of polymer (polymer at bottom of photo); and calcification of the flexing bladder of a ventricular assist pump removed from a person after 257 days. (C) Gross photograph. Calcific masses are noted by arrows. (D) photomicrograph (B) and (D) von Kossa stain (calcium phosphates black) 100×.

Calcific deposits associated with polymeric heart valve or blood pump components can occur either within the adherent layer of deposited thrombus, proteins, and cells (pseudointima) on the blood-contacting surface (extrinsic mineralization) or is below the surface (intrinsic calcification) (Joshi et al., 1996). In some cases, calcific deposits are associated with microscopic surface defects, originating either during bladder fabrication or resulting from cracking during function.

Breast Implants

Calcification of silicone-gel breast implant capsules occurs as discrete calcified plaques at the interface of the inner fibrous capsule with the implant surface (Peters and smith, 1998; Gumus, 2009). Capsular calcification has also been encountered with breast implants in patients with silicone envelopes filled with saline. Calcification could interfere with effective tumor detection and diagnosis, which could potentially delay treatment, particularly in patients who have breast implants following reconstructive surgery for breast cancer. In a study of breast implants removed predominantly for capsular contraction, 16% overall demonstrated calcific deposits, including 26% of implants inserted for 11–20 years, and all those inserted for more than 23 years (Peters and Smith, 1995). Another study demonstrated calcification associated with virtually all implants examined after more than 20 years (Legrand et al., 2005).

Ivalon® (polyvinyl alcohol) sponge prostheses, used quite extensively during the 1950s, were also frequently associated with calcification. In Japan, where augmentation mammoplasty was frequently performed using injection of foreign material (liquid paraffin from approximately 1950 until 1964, and primarily liquid silicone injections thereafter), the incidence of calcification has been much higher. One study showed calcification in 45% of breast augmentations which were done by injection (Koide and Katayama, 1979).

Intrauterine Contraceptive Devices

Intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUDs) are composed of plastic or metal, and placed in a woman’s uterus chronically to prevent implantation of a fertilized egg. Device dysfunction due to calcific deposits can be manifested as contraceptive failure or device expulsion. For example, accumulation of calcific plaque could prevent the release of the active contraception-preventing agent – either ionic copper from copper-containing IUDs or an active agent from hormone-releasing IUD systems. Studies of explanted IUDs using transmission and electron microscopy coupled with X-ray microprobe analysis have shown that surface calcium deposition is virtually ubiquitous, but highly variable among patients (Khan and Wikinson, 1985; Patai et al., 1998).

Urinary Stents and Prostheses

Mineral crusts form on the surfaces of urinary stents and nephrostomy tubes, which are used extensively in urology to alleviate urinary obstruction or incontinence (Goldfarb et al., 1989; Vanderbrink et al., 2008). Observed in both male and female urethral implants and artificial ureters, this calcification can lead to obstruction and device failure. The mineral crust typically consists of either calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate mineral such as hydroxyapatite or struvite, an ammonium- and magnesium-containing phosphate mineral derived from urine. There is some evidence that encrustation may both result from and predispose to bacterial infection.

Intraocular and Soft Contact Lenses and Scleral Buckles

Calcium phosphate deposits can opacify intraocular and soft contact lenses, typically composed of poly-2-hydroxyethyl-methacrylate (HEMA) (Bucher et al., 1995; Nakanome et al., 2008; Neuhann et al., 2008; Rimmer et al., 2010). Calcium from tear fluid is considered to be the source of the deposits found on HEMA contact lens, and calcification may be potentiated in patients with systemic and ocular conditions associated with elevated tear calcium levels (Klintworth et al., 1977). Encircling scleral bands, used in surgery for retinal detachment, and composed of silicone or hydrogel materials, also calcify (Lane et al., 2001).

Assessment of Biomaterials Calcification

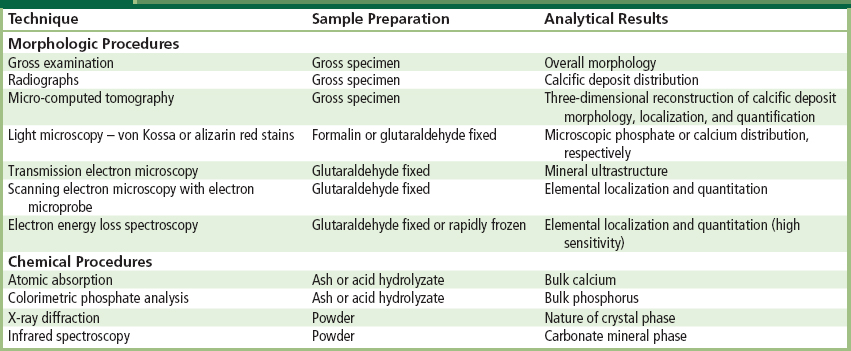

Calcific deposits are investigated using morphologic and chemical techniques (Table II.4.5.2). Morphologic techniques facilitate detection and characterization of the microscopic and ultrastructural sites and distribution of calcific deposits, and their relationship or tissue or biomaterials structural details. Such analyses directly yield important qualitative (but not quantitative) information. In contrast, chemical techniques, which require destruction of the tissue specimen, permit identification and quantitation of both bulk elemental composition and determination of crystalline mineral phases. However, such techniques generally cannot relate the location of the mineral to the details of the underlying tissue structure. The most comprehensive studies use several analytical modalities to simultaneously characterize both morphologic and chemical aspects of calcification. Moreover, newer techniques are available for non-destructive and potentially non-invasive characterizing of calcification, both in specimens (microcomputer tomography (micro CT)) (Ford-Hutchinson, 2003; Neues and Epple, 2008), and in vivo using molecular imaging (Aikawa et al., 2007). Micro CT has been used extensively in studies of bone regenerative biomaterials (Jiang et al., 2009). Molecular imaging, which probes biomarkers of particular targets or pathways of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of calcification, is particularly exciting in this context to enable the visualization of the ongoing and dynamic process of calcification, potentially quantitatively and repetitively in living organisms (New and Aikawa, 2011).

TABLE II.4.5.2 Methods for Assessing Calcification

Morphologic Evaluation

Morphologic assessment of calcification is done by means of several readily available and well-established techniques that range from macroscopic (gross) examination and radiographs (X-rays) of explanted prostheses to sophisticated electron energy loss spectroscopy. Each technique has advantages and limitations; several techniques are often used in combination to obtain an understanding of the structure, composition, and mechanism of each type of calcification.

Careful visual examination of the specimen, often under a dissecting (low power) microscope, and radiography assess distribution of mineral. Specimen radiography typically involves placing the explanted prosthesis on an X-ray film plate and exposing to an X-ray beam in a special device used for small samples (e.g., we use the Faxitron, Hewlett-Packard, McMinnville, CA with an energy level of 35 keV for 1 minute for valves). Deposits of mineral appear as bright densities which have locally blocked the beam from exposing the film (see Figure II.4.5.1B).

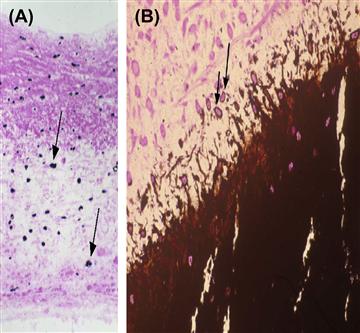

Light microscopy of calcified tissues is widely used. Identification of mineral is facilitated through the use of either calcium- or phosphorus-specific stains, such as alizarin red (which stains calcium) or von Kossa (which stains phosphates brown-black) (Figure II.4.5.2B and Figure II.4.5.3). These histologic stains are readily available, can be easily applied to tissue sections embedded in either paraffin or plastic, and are most useful for confirming and characterizing suspected calcified areas which have been noted by routine hematoxylin and eosin staining techniques. Sectioning of calcified tissue which has been embedded in paraffin often leads to considerable artifacts due to fragmentation; embedding of tissue with calcific deposits in a harder medium such as glycolmethacrylate polymer can yield superior section quality.

FIGURE II.4.5.3 Light microscopic appearance of calcification of experimental porcine aortic heart valve tissue. Note cell-based orientation of initial deposits (arrows). (A) Implanted subcutaneously in three-week-old rats for 72 hours; (B) implanted in growing sheep for five months, demonstrating predominant site of growing edge of calcification in cells of the residual porcine valve matrix (arrows).

((B) Reproduced by permission from Schoen, F. J. (2001). Pathology of heart valve substitution with mechanical and tissue prostheses, In: Cardiovascular Pathology, 3rd edn., Silver, M. D., Gotlieb, A. I. & Schoen, F. J. (Eds.). W. B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, pp. 629–677.)

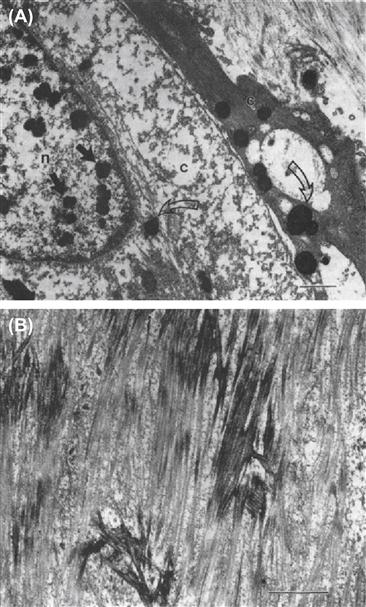

Electron microscopic techniques, which involve the bombardment of the specimen with a highly focused electron beam in a vacuum, have much to offer in the determination of early sites of calcific deposits. In transmission electron microscopy (TEM), the beam traverses an ultra-thin section (0.05 μm) (Figure II.4.5.4); observation of the ultrastructure (submicron tissue features) of calcification by TEM facilitates the understanding of the mechanisms by which calcific crystals form. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images the specimen surface, and can be coupled with elemental localization by energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDXA), allowing a semi-quantitative evaluation of the local progression of calcium and phosphate deposition in a site-specific manner. Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) couples transmission electron microscopy with highly sensitive elemental analyses to provide a most powerful localization of incipient nucleation sites and early mineralization (Webb et al., 1991). In general, the more highly sensitive and sophisticated morphologic techniques require more demanding and expensive preparation of specimens to avoid unwanted artifacts. Forethought about, and careful planning of, specimen handling optimizes the yield provided by the array of available techniques, and allows multiple approaches to be used on specimens from a particular experiment.

FIGURE II.4.5.4 Transmission electron microscopy of calcification of experimental porcine aortic heart valve implanted subcutaneously in three-week-old rats. (A) 48-hour implant demonstrating focal calcific deposits in nucleus of one cell (closed arrows) and cytoplasm of two cells (open arrows), n, nucleus; c, cytoplasm. (B) 21-day implant demonstrating collagen calcification. Bar = 2 μm. Ultrathin sections stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate.

(Figure (A) reproduced with permission from Schoen, F. J. et al. (1985), p.521.)

Chemical Assessment

Quantitation of calcium and phosphorus in biomaterial calcifications permits characterization of the progression of deposition, comparison of severity of deposition among specimens, and determination of the effectiveness of preventive measures (Levy et al., 1983a, 1985a; Schoen et al., 1985, 1986, 1987; Schoen and Levy, 1999). However, such techniques destroy the specimen (and hence obliterate any spatial information) during preparation. Calcium has been quantitated by atomic absorption spectroscopy of acid-hydrolyzed or ashed samples. Phosphorus is usually quantitated as phosphate, using a molybdate complexation technique with spectrophotometric detection. The specific crystalline form of the mineral phase can be determined by X-ray diffraction. Carbonate-containing mineral phases may also be analyzed by infrared spectroscopy.

Mechanisms of Biomaterials Calcification

Regulation of Pathologic Calcification

The determinants of biomaterial mineralization include factors related to: (1) host metabolism; (2) implant structure and chemistry; and (3) mechanical factors. Natural cofactors and inhibitors may also play a role (see below). The most important host metabolic factor relates to young age, with more rapid calcification taking place in immature patients or experimental animals (Levy et al., 1983a). Although the relationship is well-established, the mechanisms accounting for this effect are uncertain. An important implant factor for bioprosthetic tissue is pretreatment with glutaraldehyde, done to preserve the tissue (Golomb et al., 1987; Grabenwoger et al., 1996). It has been hypothesized that the cross-linking agent glutaraldehyde stabilizes and perhaps modifies phosphorous-rich calcifiable structures in the bioprosthetic tissue. These sites seem to be capable of mineralization upon implantation when exposed to the comparatively high calcium levels of extracellular fluid. Calcification of the two principal types of tissue used in bioprostheses – glutaraldehyde-pretreated porcine aortic valve or glutaraldehyde-pretreated bovine pericardium – is similar in extent, morphology, and mechanisms (Schoen and Levy, 2009).

The determinants of biomaterial mineralization include factors related to: (1) host metabolism; (2) implant structure and chemistry; and (3) mechanical factors. Natural cofactors and inhibitors may also play a role.

Calcification has typically been considered a passive, unregulated, and degenerative process. However, the observations of matrix vesicles, hydroxyapatite mineral, and bone-related morphogenetic and non-collagenous proteins in situations of pathological calcification has suggested that the mechanisms responsible for pathologic calcification may be regulated, similarly to physiologic mineralization of bone and other hard tissues, and that some of the mechanisms regulating these paradoxically different processes may be shared (Johnson et al., 2006; Demer and Tintut, 2008; Persy and D’Haese, 2009). In normal blood vessels and valves, inhibitory mechanisms outweigh procalcification inductive mechanisms; in contrast, in bone and pathologic tissues, inductive mechanisms dominate. Naturally-occurring inhibitors to crystal nucleation and growth (of which at least 11 have been identified), may also play a role in biomaterial and other cardiovascular calcification (Weissen-Plenz et al., 2008). Specific inhibitors in this context include osteopontin (Steitz et al., 2002) and phosphocitrate (Tew et al., 1980). Naturally-occurring mineralization cofactors, such as inorganic phosphate (Jono et al., 2000), bone morphogenic protein (a member of the transforming growth factor (TGF) beta family) (Bostrom et al., 1993), pro-inflammatory lipids (Demer, 2002), and other substances (e.g., cytokines) may also play a role in pathologic calcification. The non-collagenous proteins osteopontin, TGF-beta1, and tenascin-C involved in bone matrix formation and tissue remodeling have been demonstrated in clinical calcified bioprosthetic heart valves, natural valves, and atherosclerosis, suggesting that they play a regulatory role in these forms of pathologic calcification in humans (Srivasta et al., 1997; Bini et al., 1999; Jian et al., 2001, 2003), but a direct relationship has not yet been demonstrated.

Mechanical factors also regulate calcification. Both intrinsic and extrinsic mineralization of a biomaterial is generally enhanced at the sites of intense mechanical deformations generated by motion, such as the points of flexion in heart valves (Thubrikar et al., 1983). The mechanisms underlying mechanical potentiation of calcification associated with biomaterials are incompletely understood, but the effect mimics the well-known Wolf’s law in bone, in which formation and adaptation occurs in response to the mechanical forces that it experiences (Chen et al., 2010). Moreover, the enhancement is seen in systems where static but not dynamic mechanical strain is applied (Levy, 1983a), and in systems where live stem cells are subjected to a spectrum of mechanical environments (Yip et al., 2009).

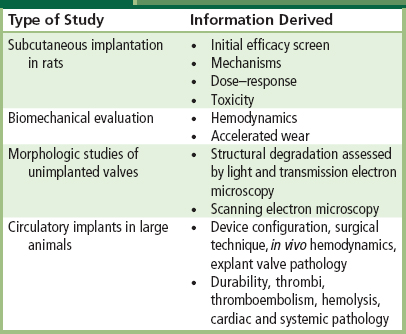

Experimental Models for Biomaterials Calcification

Animal models have been developed for the investigation of the calcification of bioprosthetic heart valves, aortic homografts, cardiac assist devices, and trileaflet polymeric valves (Table II.4.5.3). The most widely used experimental models used to investigate the pathophysiology of bioprosthetic tissue calcification, and as a preclinical screen of new or modified materials and design configurations, include tricuspid or mitral replacements or conduit-mounted valves in sheep or calves, and isolated tissue (i.e., not in a valve) samples implanted subcutaneously in mice, rabbits or rats (Levy et al., 1983a; Schoen et al., 1985, 1986). In both circulatory and non-circulatory models, bioprosthetic tissue calcifies progressively with a morphology similar to that observed in clinical specimens, but with markedly accelerated kinetics. In vitro models of biomaterials calcification have been investigated, but have not been useful in studying mechanisms or preventive strategies (Schoen et al., 1992a; Mako and Vesely, 1997).

TABLE II.4.5.3 Experimental Models of Calcification

| Type | System | Typical Duration |

| Calcification of bioprosthetic or other tissue heart valve | In vitro incubation of tissue fragment or flexing valvesRat subdermal implant of tissue fragmentCalf or sheep orthotopic valve replacementRat or sheep descending aorta | Days to weeks 3 weeks 3–5 months 1–5 months |

| Calcification of polyurethane | Rat subdermal implant of material sample | 1–2 months |

| Calf or sheep artificial heart implant | 5 months | |

| Trileaflet polymeric valve implant in calf or sheep | 5 months | |

| Calcification of hydrogel | Rat subdermal implant of material sample | 3 weeks |

| Calcification of collagen | Rat subdermal implant of material sample | 3 weeks |

| Urinary encrustation | In vitro incubation | Hours to days |

| In vivo bladder implants (rats and rabbits) | 10 weeks |

Compared with the several years normally required for calcification of clinical bioprostheses, valve replacements in sheep or calves calcify extensively in three to six months (Schoen et al., 1985, 1986, 1994). However, expense, technical complexity, and stringent housing and management procedures pose important limitations to all the circulatory models using large animals. In addition, implantation in the heart requires the use of complex surgical procedures utilizing cardiopulmonary bypass, as well as a high level of surgical expertise and postoperative care. These limitations stimulated the development of subdermal (synonym subcutaneous – under the skin) implant models. Subdermal bioprosthetic implants in rats, rabbits, and mice provide the following useful features: (1) calcification occurs at a markedly accelerated rate in a morphology comparable to that seen in circulatory explants; (2) the model is economical so that many specimens can be studied with a given set of experimental conditions, thereby allowing quantitative characterization and statistical comparisons; and (3) specimens are easily and quickly retrieved from the experimental animals, facilitating the careful manipulation and rapid processing required for detailed analyses (Levy et al., 1983; Schoen et al., 1985, 1986).

Thus, the subcutaneous model is a technically convenient and economically advantageous vehicle for investigating host and implant determinants and mechanisms of mineralization, as well as for screening potential strategies for its inhibition (anticalcification). Promising approaches may be investigated further in a large animal valve implant model. Large animal implants as valve replacements are also used: (1) to elucidate further the processes accounting for clinical failures; (2) to evaluate the performance of design and biomaterials modifications in valve development studies; (3) to assess the importance of blood–surface interactions; and (4) to provide data required for approval by regulatory agencies (Schoen, 1992b and 1994). Polyurethane calcification has also been studied with subdermal implants in rats (Joshi et al., 1996).

Pathophysiology of Bioprosthetic Heart Valve Calcification

Data from valve explants from patients and subdermal and circulatory experiments in animal models using bioprosthetic heart valve tissue have elucidated the pathophysiology of this important clinical problem, and enhanced our understanding of pathologic calcification in general (Figure II.4.5.4). The similarities of calcification in the different experimental models and clinical bioprostheses suggest a common pathophysiology, independent of implant site. Calcification appears to depend on exposure of a susceptible substrate to extracellular fluid; mechanical factors and local implant-related or circulating substances may play regulatory roles. However, since the morphology and extent of calcification in subcutaneous implants is analogous to that observed in clinical and experimental circulatory implants, despite the lack of dynamic mechanical activity characteristic of the circulatory environment, it is clear that dynamic stress promotes, but is not prerequisite for, calcification of bioprosthetic tissue. Interestingly, in the subcutaneous model, calcification is enhanced in areas of tissue folds, bends, and areas of shear, suggesting that static mechanical deformation also potentiates mineralization (Levy et al., 1983a). Although these data suggest that local tissue disruption mediates the mechanical effect, the precise mechanisms by which mechanical factors influence calcification are uncertain.

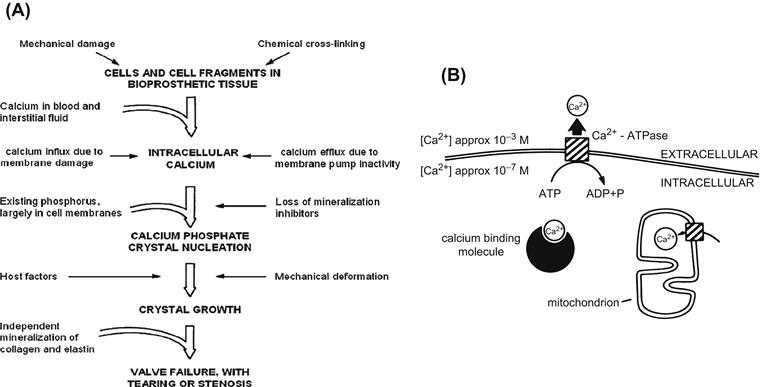

FIGURE II.4.5.5 Extended hypothetical model for the calcification of bioprosthetic tissue. (A) Overall model, which considers host factors, implant factors, and mechanical damage, and relates initial sites of mineral nucleation to increased intracellular calcium in residual cells and cell fragments in bioprosthetic tissue. The ultimate result of calcification is valve failure, with tearing or stenosis. The key contributory role of existing phosphorus in membrane phospholipids and nucleic acids in determining the initial sites of crystal nucleation is emphasized, and a possible role for the independent mineralization of collagen is acknowledged. Mechanical deformation probably contributes to both nucleation and growth of calcific crystals. (B) Events at the cell membrane and other calcium-binding structures. There is a substantial physiologic (normal) gradient of free calcium across the cell membrane (10−3 M outside, 10−7 M inside) which is maintained as an energy-dependent process. With cell death or membrane dysfunction, calcium phosphate formation can be initiated at the membranous cellular structures.

((A) Reproduced by permission from Schoen, F. J. & Levy, R. J. (2005). Calcification of tissue heart valve substitutes: Progress toward understanding and prevention. Ann. Thorac. Surg., 79, 1072–1080. (B) Reproduced by permission from Schoen, F. J. et al. (1988). Biomaterials-associated calcification: Pathology, mechanisms, and strategies for prevention. J. Appl. Biomater., 22, 11–36.)

Although a potential role for inflammatory and immune processes has been postulated by some investigators (Love, 1993; Human and Zilla, 2001a,b), no definite role has been demonstrated for circulating cells, and many lines of evidence suggest that neither nonspecific inflammation nor specific immunologic responses appear to favor bioprosthetic tissue calcification. Proponents of an immunological mechanism for failure cite that: (1) experimental animals can be sensitized to both fresh and cross-linked bioprosthetic valve tissues; (2) antibodies to valve components can be detected in some patients following valve dysfunction; and (3) some failed tissue valves have brisk mononuclear inflammation, no causal immunologic basis has been demonstrated for bioprosthetic valve calcification. However, calcification in either circulatory or subcutaneous locations is not usually associated with inflammation. Moreover, in experiments in which valve cusps were enclosed in filter chambers that prevent host cell contact with tissue, but allow free diffusion of extracellular fluid and implantation of valve tissue in congenitally athymic (“nude”) mice who have essentially no T-cell function, calcification morphology and extent are unchanged (Levy et al., 1983a,b). Clinical and experimental data detecting antibodies to valve tissue after failure may reflect a secondary response to valve damage, rather than a cause of failure.

Glutaraldehyde pretreatment of tissues or severe anoxia/hypoxia/ischemia leading to cell death in natural tissues or tissue-based biomaterials engenders cell injury. Consistent with a dystrophic mechanism, the initial calcification sites in bioprosthetic tissue are predominantly dead cells and cell membrane fragments (Levy et al., 1983a; Schoen et al., 1985, 1986; Schoen and Levy, 1999) (see Figure II.4.5.4). In non-functional cells or cells which have been rendered non-viable by glutaraldehyde fixation, the normal cellular handling of calcium ions is disrupted. Normally, plasma calcium concentration is 1 mg/ml (approximately 10−3 M); since the membranes of healthy cells pump calcium out, the concentration of calcium in the cytoplasm is 1000–10,000 times lower (approximately 10−7 M). The cell membranes and other intercellular structures are high in phosphorus (as phospholipids, especially phosphatidyl serine, which can bind calcium); they can serve as nucleators. Mitochondria are also enriched in calcium. Other initiators under various circumstances include collagen and elastic fibers of the extracellular matrix, denatured proteins, phosphoproteins, fatty acids, blood platelets and, in the case of infection, bacteria. We have previously hypothesized that cells calcify after glutaraldehyde pretreatment because this cross-linking agent stabilizes all the phosphorous stores, but the normal mechanisms for elimination of calcium from the cells are not available in glutaraldehyde-pretreated tissue (Schoen et al., 1986). Initial calcification deposits eventually enlarge and coalesce, resulting in grossly mineralized nodules that cause prostheses to malfunction.

Calcification of the adjacent aortic wall portion of glutaraldehyde-pretreated porcine aortic valves, and valvular allografts and vascular segments, is also observed clinically and experimentally. Mineral deposition occurs throughout the vascular cross-section, but is accentuated in the dense bands at the inner and outer media, and cells and elastin (itself not a prominent site of mineralization in cusps) are the major sites. In non-stented porcine aortic valves which have greater portions of aortic wall exposed to blood than in currently used stented valves, calcification of the aortic wall could stiffen the root, altering hemodynamic efficiency, causing nodular calcific obstruction, potentiating wall rupture or providing a nidus for emboli. Some anticalcification agents (see later), including 2-amino-oleic acid (AOA) and ethanol, prevent experimental cuspal but not aortic wall calcification (Chen et al., 1994a,b).

Calcification of Collagen and Elastin

Calcification of the extracellular matrix structural proteins collagen and elastin has been observed in clinical and experimental implants of bioprosthetic and homograft valvular and vascular tissue, and has been studied using a rat subdermal model. Collagen-containing implants are widely used in various surgical applications, such as tendon prostheses and surgical absorptive sponges, but their usefulness is compromised owing to calcium phosphate deposits and the resultant stiffening. Cross-linking by either glutaraldehyde or formaldehyde promotes the calcification of collagen sponge implants made of purified collagen, but the extent of calcification does not correlate with the degree of cross-linking (Levy et al., 1986). Elastin calcification has also been studied (Vyavahare et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2006).

Prevention of Calcification

Three strategies have been investigated for preventing calcification of biomaterial implants: (1) systemic therapy with anticalcification agents; (2) local therapy with implantable drug delivery devices; and (3) biomaterial modifications, whether by removal of a calcifiable component, addition of an exogenous agent or chemical alteration. The subcutaneous model has been widely used to screen potential strategies for calcification inhibition (anticalcification or antimineralization). Promising approaches have been investigated further in a large animal valve implant model. However, strategies that appeared efficacious in subcutaneous implants have not always proven favorable when used on valves implanted into the circulation (see below).

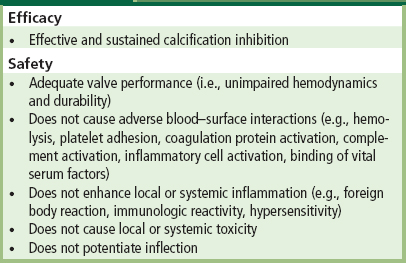

Analogous to any new or modified drug or device, a potential antimineralization treatment must be effective and safe. The treatment should not impede valve performance such as hemodynamics. Investigations of an anticalcification strategy must demonstrate not only the effectiveness of the therapy, but also the absence of adverse effects (Schoen et al., 1992b). Adverse effects in this setting could include systemic or local toxicity, tendency toward thrombosis on infection, and induction of immunological effects or structural degradation, with either immediate loss of mechanical properties or premature deterioration and failure. Indeed, there are several examples whereby an antimineralization treatment contributed to unacceptable degradation of the tissue (Jones et al., 1989; Gott et al., 1992; Schoen, 1998). The treatment should not impede normal valve performance, such as hemodynamics and durability. As summarized in more detail in Table II.4.5.4, a rational approach for preventing bioprosthetic calcification must integrate safety and efficacy considerations with the scientific basis for inhibition of calcium phosphate crystal formation. This will of necessity involve the steps summarized in Table II.4.5.5, before appropriate clinical trials can be undertaken (Schoen et al., 1992b; Vyavahare et al., 1997a).

TABLE II.4.5.4 Criteria for Efficacy and Safety of Antimineralization Treatments

(Modified from Schoen F.J. et al. (1992). Antimineralization treatments for bioprosthetic heart valves. Assessment of efficacy and safety. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg., 104,1285–1288.)

TABLE II.4.5.5 Preclinical Efficacy and Safety Testing of Antimineralization Treatments

Experimental studies using bioprosthetic tissue implanted subcutaneously in rats have clearly demonstrated that adequate doses of systemic agents used to treat clinical metabolic bone disease can prevent its calcification (Levy et al., 1987). However, systemic therapy with anticalcification agents may be efficacious, but is unlikely to be safe. Sufficient doses of systemic agents used to treat clinical metabolic bone disease, including calcium chelators (e.g., diphosphonates such as ethane hydroxybisphosphonate (EHBP)), can prevent the calcification of bioprosthetic tissue implanted subcutaneously in rats. However, because they also interfere with physiologic calcification (i.e., bone growth), systemic drug administration is associated with many side-effects in calcium metabolism, and animals receiving doses sufficient to prevent bioprosthetic tissue calcification suffer growth retardation. Thus, the principal disadvantage of the systemic use of anticalcification agents for preventing pathologic calcification is the consequent inhibition of bone formation and body growth. To avoid this difficulty, approaches for preventing the calcification of bioprosthetic heart valves have been based on co-implants of a drug delivery system adjacent to the prosthesis, in which the effective drug concentration would be confined to the site where it is needed (i.e., the implant), and systemic side-effects would be prevented (Levy et al., 1985b). A localized anticalcification effect would be particularly attractive in young people. Studies incorporating EHBP in nondegradable polymers, such as ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA), polydimethylsiloxane (silicone), silastic, and polyurethanes have shown the effectiveness of this strategy in animal models. This approach, however, has been difficult to implement clinically.

The approach which is most likely to yield an improved clinical valve in the short-term involves modification of the substrate, either by removing or altering a calcifiable component or binding an inhibitor. Forefront strategies should also consider: (1) a possible synergism provided by multiple anticalcification agents and approaches used simultaneously; (2) new materials; and (3) the possibility of tissue-engineered heart valve replacements. The agents most widely studied, for efficacy, mechanisms, lack of adverse effects, and potential clinical utility are summarized below and in Table II.4.5.6. Combination therapies using multiple agents may provide synergy of beneficial effects (Levy et al., 2003), potentially permitting simultaneous prevention of calcification in both cusps and aortic wall, particularly beneficial in stentless aortic valves.

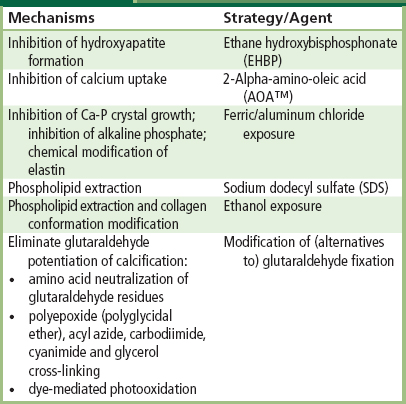

TABLE II.4.5.6 Prototypical Agents for Mechanism-Based Prevention of Calcification in Bioprosthetic Heart Valves

AOA™ (2-α-amino-oleic acid) is a trademark of Biomedical Designs, Inc., of Atlanta, GA, USA.

Inhibitors of Hydroxyapatite Formation

Bisphosphonates

Ethane hydroxybisphosphonate (EHBP) has been approved by the FDA for human use to inhibit pathologic calcification, and to treat hypercalcemia of malignancy. Compounds of this type probably inhibit calcification by poisoning the growth of calcific crystals. Either cuspal pretreatment or systemic or local therapy of the host with diphosphonate compounds inhibits experimental bioprosthetic valve calcification (Levy et al., 1985, 1987; Johnston et al., 1993). Recently, controlled clinical trials which have orally administered bisphosphonates have demonstrated the ability to stabilize osteoporosis. These agents, such as Alendronate (Phosphomax®, Merck, Inc.) are hypothesized to act by stabilizing bone mineral.

Trivalent Metal Ions

Pretreatment of bioprosthetic tissue with iron and aluminum (e.g., FeCl3 and AlCl3) inhibits calcification of subdermal implants with glutaraldehyde-pretreated porcine cusps or pericardium (Webb et al., 1991; Carpentier et al., 1997). Such compounds are hypothesized to act through complexation of the cation (Fe or Al) with phosphate, thereby preventing calcium phosphate formation. Both ferric ion and the trivalent aluminum ion inhibit alkaline phosphatase, an important enzyme used in bone formation. This may be related to their mechanism for preventing initiation of calcification. Furthermore, research from our laboratories has demonstrated that aluminum chloride prevents elastin calcification through a permanent structural alteration of the elastin molecule. These compounds are also active when released from polymeric controlled-release implants.

Calcium Diffusion Inhibitor

Amino-oleic Acid

2-alpha-amino-oleic acid (AOA™, Biomedical Designs, Inc., Atlanta, GA) bonds covalently to bioprosthetic tissue through an amino linkage to residual aldehyde functions, and inhibits calcium flux through bioprosthetic cusps (Chen et al., 1991, 1994a). AOA™ is effective in mitigating cusp, but not aortic wall, calcification in rat subdermal and cardiovascular implants. This compound is used in FDA-approved porcine aortic valves (Fyfe and Schoen, 1999; Celiento et al., 2012; El-Hamamsy et al., 2011).

Removal/Modification of Calcifiable Material

Surfactants

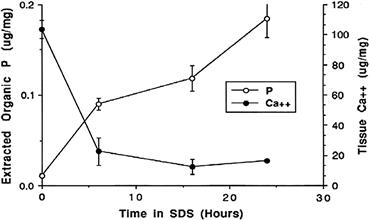

Incubation of bioprosthetic tissue with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and other detergents extracts the majority of acidic phospholipids (Hirsch et al., 1993); this is associated with reduced mineralization, probably resulting from suppression of the initial cell-membrane oriented calcification (Figure II.4.5.6). This compound is used in an FDA-approved porcine valve (David et al., 1998; Bottio et al., 2003).

FIGURE II.4.5.6 Reduction of calcification of bioprosthetic tissue by preincubation in 1% SDS demonstrated in a rat subcutaneous model of glutaraldehyde cross-linked porcine aortic valve. These results support the concept that phospholipid extraction is an important but perhaps not the only mechanism of SDS efficacy.

(Reproduced by permission from Schoen, F. J., Levy, R. J. & Piehler, H. R. (1992). Pathological considerations in replacement cardiac valves. Cardiovasc. Pathol., 1, 29–52.)

Ethanol

Ethanol preincubation of glutaraldehyde-cross-linked porcine aortic valve bioprostheses prevents calcification of the valve cusps in both rat subdermal implants, and sheep mitral valve replacements (Vyavahare et al., 1997b, 1998). Eighty percent ethanol pretreatment: (1) extracts almost all phospholipids and cholesterol from glutaraldehyde-cross-linked cusps; (2) causes a permanent alteration in collagen conformation as assessed by Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR); (3) affects cuspal interactions with water and lipids; and (4) enhances cuspal resistance to collagenase. Ethanol is in clinical use as a porcine valve cuspal pretreatment in both Europe and the United States, and use in combination with aluminum treatment of the aortic wall of a stentless valve is under consideration.

Decellularization

Since the initial mineralization sites are devitalized connective cells of bioprosthetic tissue, these cells may be removed from the tissue, with the intent of making the bioprosthetic matrix less prone to calcification (Courtman et al., 1994; Wilson et al., 1995).

Use of Tissue Fixatives Other than Glutaraldehyde, and Modification of Glutaraldehyde Fixation

Since previous studies have demonstrated that conventional glutaraldehyde fixation is conducive to calcification of bioprosthetic tissue, several studies have investigated modifications of, and alternatives to, conventional glutaraldehyde pretreatment. For example, and paradoxically, fixation of bioprosthetic tissue by extraordinarily high concentrations of glutaraldehyde (5–10× those normally used) appear to inhibit calcification (Zilla et al., 1997, 2000); moreover, residual glutaraldehyde residues in bioprosthetic tissue can be neutralized (“detoxified”) by treatment with lysine or diamine, this inhibits calcification of subdermal implants (Grabenwoger et al., 1992; Zilla et al., 2000, 2005; Trantina-Yates et al., 2003).

Nevertheless, there is presently no mechanistic explanation for these glutaraldehyde-related observations. Non-glutaraldehyde cross-linking of bioprosthetic tissue with epoxides, carbodiimides, acylazides, and other compounds reduces their calcification in rat subdermal implant studies (Xi et al., 1992; Myers et al., 1995), and with triglycidylamine (TGA), an epoxy cross-linker (Connolly et al., 2011) and photooxidative preservative in large animal implants in sheep (Moore and Phillips, 1997).

Alternative Materials

Polyurethane trileaflet valves have been fabricated and investigated as a possible alternative to bioprostheses or mechanical valve prostheses (Ghanbari et al., 2009). Despite versatile properties, such as superior abrasion resistance, hydrolytic stability, high flexural endurance, excellent physical strength, and acceptable blood compatibility, the use of polymers has been hampered by calcification, thrombosis, tearing, and biodegradation. Although the exact mechanism of polyurethane calcification is as yet unclear, it is believed that several physical, chemical, and biologic factors (directly or indirectly) play an important role in initiating this pathologic disease process (Schoen et al., 1992c; Joshi et al., 1996; Hyde et al., 1999).

Conclusions

Calcification of biomaterial implants is an important pathologic process affecting a variety of tissue-derived biomaterials, as well as synthetic polymers in various functional configurations. The pathophysiology has been partially characterized with a number of useful animal models; a key common feature is the involvement of devitalized cells and cellular debris. Clinically useful preventive approaches based on either modifying biomaterials or local drug administration appear to be promising in some contexts.

Bibliography

1. Aikawa E, Nahrendorf M, Figueiredo JL, Swirski FK, Shtatland T, et al. Osteogenesis associates with inflammation in early-stage atherosclerosis evaluated by molecular imaging in vivo. Circulation. 2007;116:2841–2850.

2. Anderson HC. Mechanisms of pathologic calcification. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 1988;14:303–319.

3. Anderson HC. Mechanism of mineral formation in bone. Lab Invest. 1989;60:320–330.

4. Barrere F, van Blitterswijk CA, de Groot K. Bone regeneration: Molecular and cellular interactions with calcium phosphate ceramics. Int J Nanomed. 2006;1:317–332.

5. Bass JK, Chan GM. Calcium nutrition and metabolism during infancy. Nutrition. 2006;22:1057–1066.

6. Bechtel JF, Muller-Steinhardt M, Schmidtke C, Bruswik A, Stierle U, et al. Evaluation of the decellularized pulmonary valve homograft (SynerGraft). J Heart Valve Dis. 2003;12:734–739.

7. Bini A, Mann KG, Kudryk BJ, Schoen FJ. Non-collagenous bone proteins, calcification and thrombosis in carcinoid artery atherosclerosis. Arterio Sci Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1852–1861.

8. Bonucci E. Is there a calcification factor common to all calcifying matrices?. Scanning Microscopy. 1987;1:1089–1102.

9. Bostrom K, Watson KE, Horn S, Wortham C, Herman IM, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein expression in human atherosclerotic lesions. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1800–1809.

10. Bottio T, Thiene G, Pettenazzo E, Ius P, Bortolotti U, et al. Hancock II bioprostheses: A glance at the microscope in mid-long-term explants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:99–105.

11. Brockhurst RJ, Ward PC, Lou P, Ormerod D, Albert D. Dystrophic calcification of silicone scleral buckling implant materials. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;115:524–529.

12. Bucher PJ, Buchi ER, Daicker BC. Dystrophic calcification of an implanted hydroxyethylmethacrylate intraocular lens. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1431–1435.

13. Bueno EM, Glowacki J. Cell-free and cell-based approaches for bone regeneration. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:685–697.

14. Carpentier SM, Carpentier AF, Chen L, Shen M, Quintero LJ, et al. Calcium mitigation in bioprosthetic tissues by iron pretreatment: The challenge of iron leaching. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1514–1515.

15. Celiento M, Ravenni G, Milano AD, et al. Aortic valve replacement with Medtronic Mosaic bioprosthesis: a 13-year follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:510–515.

16. Chan V, Jamieson WR, Germann E, Chan F, Miyagishima RT, et al. Performance of bioprostheses and mechanical prostheses assessed by composites of valve-related complications to 15 years after aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:1267–1273.

17. Chen J-H, Liu C, You L, Simmons CA. Boning up on Wolff’s Law: Mechanical regulation of the cells that make and maintain bone. J Biomech. 2009;43:108–118.

18. Chen W, Kim JD, Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Effect of 2-amino oleic acid exposure conditions on the inhibition of calcification of glutaraldehyde crosslinked porcine aortic valves. J Biomed Mater Res. 1994a;28:1485–1495.

19. Chen W, Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Mechanism of efficacy of 2-amino oleic acid for inhibition of calcification of glutaraldehyde-pretreated porcine bioprosthetic valves. Circulation. 1994b;90:323–329.

20. Cheng PT. Pathologic calcium phosphate deposition in model systems. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 1988;14:341–351.

21. Coleman D, Lim D, Kessler T, Andrade JD. Calcification of nontextured implantable blood pumps. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1981;27:97–103.

22. Connolly JM, Bakay MA, Alferiev IS, et al. Triglycidylamine cross-linking combined with ethanol inhibits bioprosthetic heart valve calcification. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:858–865.

23. Courtman DW, Pereira CA, Kashef V, McComb D, Lee JM, et al. Development of a pericardial acellular matrix biomaterial: Biochemical and mechanical effects of cell extraction. J Biomed Mater Res. 1994;28:655–666.

24. Courtman DW, Pereira CA, Omar S, Langdon SE, Lee JM, et al. Biomechanical and ultrastructural comparison of cryopreservation and a novel cellular extraction of porcine aortic valve leaflets. J Biomed Mater Res. 1995;29:1507–1516.

25. David TE, Armstrong S, Sun Z. The Hancock II bioprosthesis at 12 years. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:S95–S98.

26. Demer LL. Vascular calcification and osteoporosis: Inflammatory responses to oxidized lipids. Intl J Epidemiol. 2002;31:737–741.

27. Demer LL, Tintut Y. Vascular calvification Pathobiology of a multifaceted disease. Circulation. 2008;117:2938–2948.

28. Discher DE, Mooney DJ, Zandstra PW. Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science. 2009;324:1673–1677.

29. El-Hamamsy I, Clark L, Stevens LM, et al. Late outcomes following freestyle versus homograft aortic root replacement: results from a prospective randomized trial. J Am COIL Cardiol. 2010;55:368–376.

30. Evaerts F, Torrianni M, van Luyn MJ, Van Wachem PB, Feijen J, et al. Reduced calcification of bioprostheses, cross-linked via an improved carbodiimide based method. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5523–5530.

31. Flameng W, Ozaki S, Meuris B, Herijgers P, Yperman J, et al. Antimineralization treatments in stentless porcine bioprostheses An experimental study. J Heart Valve Dis. 2001;10:489–494.

32. Fradet G, Bleese N, Busse E, Jamieson E, Raudkivi P, et al. The Mosaic valve clinical performance at seven years: Results from a Multicenter Prospective Clinical Trial. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004;13:239–247.

33. Ford-Hutchinson AF, Cooper DM, Hallgrimsson B, Jirik FR. Imaging skeletal pathology in mutant mice by microcomputed tomography. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2659–2665.

34. Fukunaga S, Tomoeda H, Ueda T, Mori R, Aovagi S, Kato S. Recurrent mitral regurgitation due to calcified synthetic chordae. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:955–957.

35. Fyfe B, Schoen FJ. Pathologic analysis of removed non-stented Medtronic Freestyle™ aortic root bioprostheses treated with amino oleic acid (AOA). Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;11(4):151–156.

36. Ghanbari H, Viatge H, Kidane AG, Burriesci G, Tavakoli M, et al. Polymeric heart valves: New materials, emerging hopes. Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:359–367.

37. Giachelli CM. Ectopic calcification: Gathering hard facts about soft tissue mineralization. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:671–675.

38. Goldfarb RA, Neerhut GJ, Lederer E. Management of acute hydronephrosis of pregnancy by urethral stenting: Risk of stone formation. J Urol. 1989;141(4):921–922.

39. Golomb G, Schoen FJ, Smith MS, Linden J, Dixon M, et al. The role of glutaraldehyde-induced crosslinks in calcification of bovine pericardium used in cardiac valve bioprostheses. Am J Pathol. 1987;127:122–130.

40. Gott JP, Chih P, Dorsey LM, Jay JL, Jett GK, et al. Calcification of porcine valves: A successful new method of antimineralization. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53:207–216.

41. Grabenwoger M, Grimm M, Ebyl E, Leukauf C, Müller MM, et al. Decreased tissue reaction to bioprosthetic heart valve material after L-glutamic acid treatment A morphological study. J Biomed Mater Res. 1992;26:1231–1240.

42. Grabenwoger M, Sider J, Fitzal F, Zelenka C, Windberger U, et al. Impact of glutaraldehyde on calcification of pericardial bioprosthetic heart valve material. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62,772–62,777.

43. Grunkemeier GL, Jamieson WR, Miller DC, Starr A. Actuarial versus actual risk of porcine structural valve deterioration. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:709–718.

44. Gümüş N. Capsular calcification may be an important factor for the failure of breast implant. Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:e606–e608.

45. Habibovic P, de Groot K. Osteoinductive biomaterials – properties and relevance in bone repair. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2007;1:25–32.

46. Harasaki H, Moritz A, Uchida N, Chen JF, McMahon JT, et al. Initiation and growth of calcification in a polyurethane coated blood pump. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1987;33:643–649.

47. Hendriks M, Eveaerts F, Verhoeven M. Alternative fixation of bioprostheses. J Long-Term Eff Med Implants. 2001;11:163–183.

48. Hilbert SL, Ferrans VJ, Tomita Y, Eidbo EE, Jones M. Evaluation of explanted polyurethane trileaflet cardiac valve prostheses. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;94:419–429.

49. Hirsch D, Drader J, Thomas TJ, Schoen FJ, Levy JT, et al. Inhibition of calcification of glutaraldehyde pretreated porcine aortic valve cusps with sodium dodecyl sulfate: Preincubation and controlled release studies. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27:1477–1484.

50. Hjortnaes J, Butcher J, Figueiredo J-H, Riccio M, Kohler RH, et al. Arterial and aortic valve calcification inversely correlates with osteoporotic bone remodeling: A role for inflammation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(16):1975–1984.

51. Hofbauer LC, Brueck CC, Shanahan CM, Schoppet M, Dobnig H. Vascular calcification and osteoporosis – clinical observation towards molecular understanding. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:251–259.

52. Human P, Zilla P. Inflammatory and immune processes: The neglected villain of bioprosthetic degeneration?. J Long-Term Eff Med Implants. 2001a;11:199–220.

53. Human P, Zilla P. The possible role of immune responses in bioprosthetic heart valve failure. J Heart Valve Dis. 2001b;10:460–466.

54. Human P, Bezuidenhout D, Torrianni M, Hendriks M, Zilla P. Optimization of diamine bridges in glutaraldehyde treated bioprosthetic aortic wall tissue. Biomaterials. 2002;23:2099–2103.

55. Hyde JA, Chinn JA, Phillips Jr RE. Polymer heart valves. J Heart Valve Dis. 1999;8:331–339.

56. Jian B, Jones PL, Li Q, Mohler 3rd ER, Schoen FJ, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 is associated with tenascin-C in calcific aortic stenosis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:321–327.

57. Jian B, Narula N, Li QY, Mohler 3rd ER, Levy RJ. Progression of aortic valve stenosis: TGF-beta 1 is present in calcified aortic valve cusps and promotes aortic valve interstitial cell calcification via apoptosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:457–465.

58. Jiang X, Zhao J, Wang S, Sun X, Zhang X, et al. Mandibular repair in rats with premineralized silk scaffolds and BMP-2 modified bMSCs. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4522–4532.

59. Johnson RC, Leopold JA, Loscalzo J. Vascular calcification Pathobiological mechanisms and clinical implications. Circ Res. 2006;99:1044–1059.

60. Johnston TP, Webb CL, Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Assessment of the in vitro transport parameters for ethanehydroxy diphosphonate through a polyurethane membrane A potential refillable reservoir drug delivery device. ASAIO. 1992;38:M611–M616.

61. Johnston TP, Webb CL, Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Site-specific delivery of ethanehydroxy diphosphonate from refillable polyurethane reservoirs to inhibit bioprosthetic tissue calcification. J Control Rel. 1993;25:227–240.

62. Jones M, Eidbo EE, Hilbert SL, Ferrans VJ, Clark RE. Anticalcification treatments of bioprosthetic heart valves: In vivo studies in sheep. J Cardiac Surg. 1989;4:69–73.

63. Jono S, McKee MD, Murry CE, Shiroi A, Nishizawa Y, et al. Phosphate regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Circ Res. 2000;87:e10–e17.

64. Joshi RR, Underwood T, Frautschi JR, Phillips Jr RE, Schoen FJ, et al. Calcification of polyurethanes implanted subdermally in rats is enhanced by calciphylaxis. J Biomed Mater Res. 1996;31,201–31,207.

65. Kantrowitz A, Freed PS, Zhou Y, et al. A mechanical auxiliary ventricle Histologic responses to long-term, intermittent pumping in calves. AS70 J. 1995;41:M340–M345.

66. Khan SR, Wilkinson EJ. Scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and electron microprobe analysis of calcific deposits on intrauterine contraceptive devices. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:732–738.

67. Kirsch T. Determinants of pathologic mineralization. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2008;18:1–9.

68. Klintworth GK, Reed JW, Hawkins HK, Ingram P. Calcification of soft contact lenses in patient with dry eye and elevated calcium concentration in tears. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1977;16:158–161.

69. Koide T, Katayama H. Calcification in augmentation mammoplasty. Radiology. 1979;130:337–338.

70. Kretlow JD, Mikos AG. Mineralization of synthetic polymer scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:927–938.

71. Kumar V, Fausto N, Aster JC, Abbas A. Robbins/Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders; 2010.

72. Lane. JI, Randall JG, Campeau NG, et al. Imaging of hydrogel episcleral buckle fragmentation as a late complication after retinal reattachment surgery. AJNRAm J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1199–1202.

73. Langer R, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260:920–926.

74. Lee JS, Basalyga DM, Simionescu A, Isenburg JC, Simionescu DT, et al. Elastin calcification in the rat subdermal model is accompanied by up-regulation of degradative and osteogenic cellular responses. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:490–498.

75. Legrand AP, Marinov G, Pavlov S, Guidoin MF, Famery R, et al. Degenerative mineralization in the fibrous capsule of silicone breast implants. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2005;16:477–485.

76. Lentz DL, Pollock EM, Olsen DB, Andrews EJ. Prevention of intrinsic calcification in porcine and bovine xenograft materials. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1982;28:494–497.

77. Levy RJ, Schoen RJ, Levy JT, Nelson AC, Howard SL, et al. Biologic determinants of dystrophic calcification and osteocalcin deposition in glutaraldehyde-reserved porcine aortic valve leaflets implanted subcutaneously in rats. Am J Pathol. 1983a;113:142–155.

78. Levy RJ, Schoen FJ, Howard SL. Mechanism of calcification of porcine aortic valve cusps: Role of T-lymphocytes. Am J Cardiol. 1983b;52:629–631.

79. Levy RJ, Hawley MA, Schoen FJ, Lund SA, Liu PY. Inhibition by diphosphonate compounds of calcification of porcine bioprosthetic heart valve cusps implanted subcutaneously in rats. Circulation. 1985;71:349–356.

80. Levy RJ, Wolfrum J, Schoen FJ, Hawley MA, Lund SA, et al. Inhibition of calcification of bioprosthetic heart valves by local controlled-released diphosphonate. Science. 1985;229:190–192.

81. Levy RJ, Schoen FJ, Sherman FS, Nichols J, Hawley MA, et al. Calcification of subcutaneously implanted type I collagen sponges: Effects of glutaraldehyde and formaldehyde pretreatments. Am J Pathol. 1986;122:71–82.

82. Levy RJ, Schoen FJ, Lund SA, Smith MS. Prevention of leaflet calcification of bioprosthetic heart valves with diphosphonate injection therapy Experimental studies of optimal dosages and therapeutic durations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;94:551–557.

83. Levy RJ, Vyavahare N, Ogle M, Ashworth P, Bianco R, et al. Inhibition of cusp and aortic wall calcification in ethanol- and aluminum-treated bioprosthetic heart valves in sheep: Background, mechanisms, and synergism. J Heart Valve Dis. 2003;12:209–216.

84. Love JW. Autologous Tissue Heart Valves. Austin, TX: R. G. Landes; 1993.

85. Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, Pinero GJ, Loyer E, et al. Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature. 1997;386:78–81.

86. Mako WJ, Vesely I. In vivo and in vitro models of calcification in porcine aortic valve cusps. J Heart Valve Dis. 1997;6:316–323.

87. Mayer Jr JE, Shin’oka T, Shum-Tim D. Tissue engineering of cardiovascular structures. Curr Opin Cardiol. 1997;12:528–532.

88. McGonagle-Wolff K, Schoen FJ. Morphologic findings in explanted Mitroflow pericardial bioprosthetic valves. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:263–264.

89. Meuris B, Phillips R, Moore MA, Flameng W. Porcine stentless bioprostheses: Prevention of aortic wall calcification by dye-mediated photooxidation. Artif Organs. 2003;27:537–543.

90. Mitchell RN, Jonas RA, Schoen FJ. Pathology of explanted cryopreserved allograft heart valves: Comparison with aortic valves from orthotopic heart transplants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:118–127.

91. Mitchell RN, Schoen FJ. Blood vessels. In: Kumar V, Fausto N, Aster JC, Abbas A, eds. Robbins/Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2010;487–528.

92. Moore, Phillips RE. Biocompatibility and immunologic properties of pericardial tissue stabilized by dye-mediated photooxidation. J Heart Valve Dis. 1997;6:307–315.

93. Myers DJ, Nakaya G, Girardot GM, Christie GW. A comparison between glutaraldehyde and diepoxide-fixed stentless porcine aortic valves: Biochemical and mechanical characterization and resistance to mineralization. J Heart Valve Dis. 1995;4:S98–S101.

94. Nakanome S, Watanabe H, Tanaka K, Tochikubo T. Calcification of Hydroview H60M intraocular lenses: Aqueous humor analysis and comparisons with other intraocular lens materials. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:80–86.

95. Neues F, Epple M. X-ray microcomputer tomography for the study of biomineralized endo- and exoskeletons of animals. Chem Rev. 2008;108:4734–4741.

96. Neuhann M, Kleinmann G, Apple DJ. A new classification of calcification of intraocular lenses. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:73–79.

97. New SE, Aikawa E. Molecular imaging insights into early inflammatory stages of arterial and aortic valve calcification. Circ Res. 2011;108:1381–1391.

98. Ogle MF, Kelly SJ, Bianco RW, Levy RJ. Calcification resistance with aluminum-ethanol treated porcine aortic valve bioprostheses in juvenile sheep. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1267–1273.

99. Parhami F, Basseri B, Hwang J, Tintut Y, Demer LL. High-density lipoprotein regulates calcification of vascular cells. Circ Res. 2002;91:570–576.

100. Patai K, Berényi M, Sipos M, Noszál B. Characterization of calcified deposits on contraceptive intrauterine devices. Contraception. 1998;58:305–308.

101. Peacock M. Calcium metabolism in health and disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:S23–S30.

102. Persy V, D’Haese P. Vascular calcification and bone disease: The calcification paradox. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:405–416.

103. Peters W, Pritzker K, Smith D, Fornasier V, Holmyard D, et al. Capsular calcification associated with silicone breast implants: Incidence, determinants, and characterization. Ann., Plast Surg. 1998;41:348–360.

104. Peters W, Smith D. Calcification of breast implant capsules: incidence, diagnosis, and contributing factors. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;34:8–11.

105. Rimmer T, Hawkesworth N, Kirkpatrick N, Price N, Manners R, et al. Calcification of Hydroview lenses implanted in the United Kingdom during 2000 and 2001. Eye (Lond.). 2010;24:199–200.

106. Schlieper G, Krűger T, Djuric Z, Damjanovic T, Markovic N, et al. Vascular access calcification predicts mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1582–1587.

107. Schoen FJ. Pathologic findings in explanted clinical bioprosthetic valves fabricated from photooxidized bovine pericardium. J Heart Valve Dis. 1998;7:174–179.

108. Schoen FJ. Pathology of heart valve substitution with mechanical and tissue prothesis. In: Silver MD, Gotlieb AI, Schoen FJ, eds. Cardiovascular Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders; 2001;629–677.

109. Schoen, Edwards WD. Pathology of cardiovascular interventions, including endovascular therapies, revascularization, vascular replacement, cardiac assist/replacement, arrhythmia control and repaired congenital heart disease. In: Silver MD, Gotlieb AI, Schoen FJ, eds. Cardiovascular Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders; 2001;678–723.

110. Schoen, Levy RJ. Tissue heart valves: Current challenges and future research perspectives. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;47:439–465.

111. Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Calcification of tissue heart valve substitutes: Progress toward understanding and prevention. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1072–1080.

112. Schoen FJ, Levy RJ, Nelson AC, Bernhard WF, Nashef A, et al. Onset and progression of experimental bioprosthetic heart valve calcification. Lab Invest. 1985;52:523–532.

113. Schoen FJ, Mitchell RN. The heart. In: Kumar V, Fausto N, Aster JC, Abbas A, eds. Robbins/Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2010;529–587.

114. Schoen, Tsao JW, Levy RJ. Calcification of bovine pericardium used in cardiac valve bioprostheses Implications for mechanisms of bioprosthetic tissue mineralization. Am J Pathol. 1986;123:143–154.

115. Schoen FJ, Kujovich JL, Webb CL, Levy RJ. Chemically determined mineral content of explanted porcine aortic valve bioprostheses: Correlation with radiographic assessment of calcification and clinical data. Circulation. 1987;76:1061–1066.

116. Schoen FJ. Biomaterials-associated calcification: Pathology, mechanisms, and strategies for prevenion. J Appl Biomater. 1988;22:11–36.

117. Schoen FJ, Golomb G, Levy RJ. Calcification of bioprosthetic heart valves: A perspective on models. J Heart Valve Dis. 1992a;1:110–114.

118. Schoen FJ, Levy RJ, Hilbert SL, Bianco RW. Antimineralization treatments for bioprosthetic heart valves Assessment of efficacy and safety. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992b;104:1285–1288.

119. Schoen FJ, Levy RJ, Piehler HR. Pathological considerations in replacement cardiac valves. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1992c;1:29–52.

120. Schoen FJ, Hirsch D, Bianco RW, Levy RJ. Onset and progression of calcification in porcine aortic bioprosthetic valves implanted as orthotopic mitral valve replacements in juvenile sheep. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:880–887.

121. Shinoka T, Ma PX, Shum-Tim D, Breuer CK, Cusick RA, et al. Tissue-engineered heart valves Autologous valve leaflet replacement study in a lamb model. Circulation. 1996;94:II-164–II-168.

122. Simon P, Kasimir MT, Seebacher G, Weigel G, Ullrich R, et al. Early failure of the tissue engineered porcine heart valve SYNERGRAFT in pediatric patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:1002–1006.

123. Speer MY, Giachelli CM. Regulation of vascular calcification. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2004;13:63–70.

124. Speer MY, McKee MD, Guldberg RE, Liaw L, Yang H-Y, et al. Inactivation of the osteopontin gene enhances vascular calcification of matrix Gla protein-deficient mice: Evidence for osteopontin as an inducible inhibitor of vascular calcification in vivo. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1047–1055.

125. Srivasta SS, Maercklein PB, Veinot J, Edwards WD, Johnson CM, et al. Increased cellular expression of matrix proteins that regulate mineralization is associated with calcification of native human and porcine xenograft bioprosthetic heart valves. J Clin Invest. 1997;5:996–1009.

126. Steitz SA, Speer MY, McKee MD, Liaw L, Almeida M, et al. Osteopontin inhibits mineral deposition and promotes regression of ectopic calcification. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:2035–2046.

127. Stock UA, Nagashima M, Khalil PN, Nollert GD, Herden T, et al. Tissue engineered valved conduits in the pulmonary circulation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;119:732–740.

128. Tew WP, Mahle C, Benavides J, Howard JE, Lehninger AL. Synthesis and characterization of phosphocitric acid, a potent inhibitor of hydroxylapatite crystal growth. Biochemistry. 1980;19:1983–1988.

129. Thoma RJ, Phillips RE. The role of material surface chemistry in implant device calcification: A hypothesis. J Heart Valve Dis. 1995;4:214–221.

130. Thubrikar MJ, Deck JD, Aouad J, Nolan SP. Role of mechanical stress in calcification of aortic bioprosthetic valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1983;86:115–125.

131. Tomizawa Y, Takanashi Y, Noishiki Y, Nishida H, Endo M, et al. Evaluation of small caliber vascular prostheses implanted in small children: Activated angiogenesis and accelerated calcification. ASAIO J. 1998;44:M496–M500.

132. Trantina-Yates AE, Human P, Zilla P. Detoxification on top of enhanced, diamine-extended glutaraldehyde fixation significantly reduces bioprosthetic root calcification in the sheep model. J Heart Valve Dis. 2003;12:93–100.

133. Umana E, Ahmed W, Alpert MA. Valvular and perivalvular abnormalities in end-stage renal disease. Am J Med Sci. 2003;325:237–242.

134. Vanderbrink BA, Rastinehad AR, Ost MC, Smith AD. Encrusted urinary stents: Evaluation and endourologist management. J Endocrinol. 2008;22:905–912.

135. Van Wachem PB, Brouwer LA, Zeeman R, Dijkstra PJ, Feijen J, et al. In vivo behavior of epoxy-crosslinked porcine heart valve cusps and walls. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;53:18–27.

136. Van Wachem PB, Brouwer LA, Zeeman R, Dijkstra PJ, Feijen J, et al. Tissue reactions to epoxy-crosslinked porcine heart valves post-treated with detergents or a dicarboxylic acid. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;55:415–423.

137. Vyavahare NR, Chen W, Joshi R, Lee C-H, Hirsch D, et al. Current progress in anticalcification for bioprosthetic and polymeric heart valves. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1997a;6:219–229.

138. Vyavahare N, Hirsch D, Lerner E, Baskin JZ, Schoen FJ, et al. Prevention of bioprosthetic heart valve calcification by ethanol preincubation Efficacy and mechanism. Circulation. 1997b;95:479–488.

139. Vyavahare NR, Hirsch D, Lerner E, Baskin JZ, Zand R, et al. Prevention of calcification of glutaraldehyde-crosslinked porcine aortic cusps by ethanol preincubation: Mechanistic studies of protein structure and water–biomaterial relationships. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;40:577–585.

140. Vyavahare N, Ogle M, Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Elastin calcification and its prevention with aluminum chloride pretreatment. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:973–982.

141. Wada T, McKee MD, Steitz S, Giachelli CM. Calcification of vascular smooth muscle cell cultures Inhibition by osteopontin. Circ Res. 1999;84:166–178.

142. Wang Q, McGoron AJ, Bianco R, Kato Y, Pinchuk L, Schoephoerster RT. In-vivo assessment of a novel polymer (SIBS) trileaflet heart valve. J Heart Valve Dis. 2010;19:499–505.

143. Weissen-Plenz G, Nitschke Y, Rutsch F. Mechanisms of arterial calcification: Spotlight on the inhibitors. Adv Clin Chem. 2008;46:263–293.

144. Webb CL, Benedict JJ, Schoen FJ, Linden JA, Levy RJ. Inhibition of bioprosthetic heart valve calcification with aminodiphosphonate covalently bound to residual aldehyde groups. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;46:309–316.

145. Webb CL, Schoen FJ, Flowers WE, Alfrey AC, Horton C, et al. Inhibition of mineralization of glutaraldehyde-pretreated bovine pericardium by AlCl3 Mechanisms and comparisons with FeCl3 LaCl3 and Ga(NO3)3 in rat subdermal model studies. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:971–981.

146. Wilson GJ, Courtman DW, Klement P, Lee JM, Yeger H. Acellular matrix: A biomaterials approach for coronary artery and heart valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:S353–S358.

147. Xi T, Ma J, Tian W, Lei X, Long S, et al. Prevention of tissue calcification on bioprosthetic heart valve by using epoxy compounds: a study of calcification tests in vitro and in vivo. J Biomed Mater Res. 1992;26:1241–1251.

148. Yip CYY, Chen J-H, Zhao R, Simmons CA. Calcification by valve interstitial cells is regulated by the stiffness of the extracellular matrix. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:936–942.

149. Yu S-Y, Viola F, Christoforidis JB, D’Amico DJ. Dystrophic calcification of the fibrous capsule around a hydrogel explant 13 years after scleral buckling surgery: Capsular calcification of a hydrogel explant. Retina. 2005;25:1104–1107.

150. Zilla P, Weissenstein C, Bracher M, Zhang Y, Koen W, et al. High glutaraldehyde concentrations reduce rather than increase the calcification of aortic wall tissue. J Heart Valve Dis. 1997;6:490–491.

151. Zilla P, Weissenstein C, Human P, Dower T, von Oppell UO. High glutaraldehyde concentrations mitigate bioprosthetic root calcification in the sheep model. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:2091–2095.

152. Zilla P, Weissenstein C, Bracher M, Human P. The anticalcific effect of glutaraldehyde detoxification on bioprosthetic aortic wall tissue in the sheep model. J Card Surg. 2001;16:467–472.

153. Zilla P, Bezuidenhout D, Torrianni M, Hendriks M, Human P. Diamine-extended glutaraldehyde- and carbodiimide crosslinks act synergistically in mitigating bioprosthetic aortic wall calcification. J Heart Valve Dis. 2005;14:538–545.