Chapter II.5.4

Artificial Cells

Basic Features of Artificial Cells

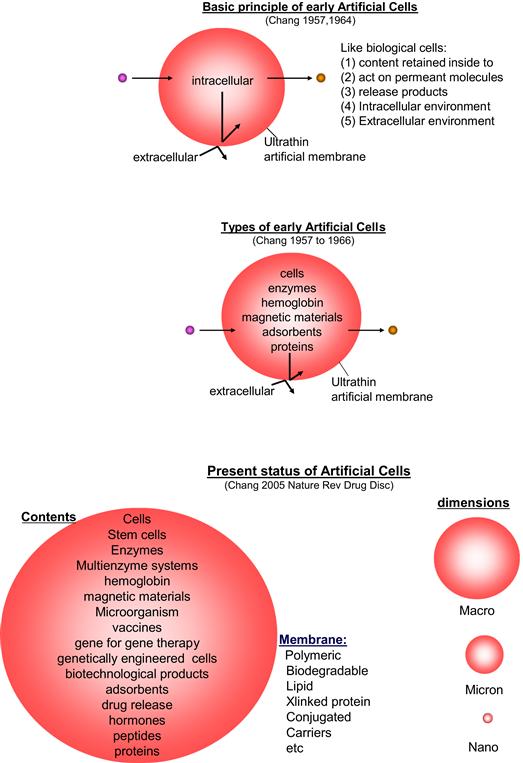

The initial research on artificial cells (Chang, 1964) forms the basic principle that has been extended for use in many areas by many groups (Chang, 2005a, 2007, 2010; Liu and Chang, 2010). Very brief examples of some of these basic features include (Figure II.5.4.1):

1. Artificial cells can contain the same biological material as biological cells. In addition, they are more versatile since adsorbents, magnetic materials, drugs, cells, stem cells, enzymes, multienzyme systems, hemoglobin, microorganisms, vaccines, gene-for-gene therapy, genetically engineered cells, hormones, peptides, and many other materials can also be included separately or in combination (Figure II.5.4.1).

2. The membrane of an artificial cell separates its content from the outside, but at the same time the membrane can be prepared to selectively allow different types of molecules to cross (Figure II.5.4.1). For example, one can prepare artificial cell membranes that selectively allow the movement of molecules according to molecular size, lipid solubility, affinity to carrier mechanisms, etc. By selecting the proper membrane material, the permeability can range from a membrane that does not allow any molecules to cross, to those that allow even very large molecules such as proteins to cross. The membrane material includes polymer, biodegradable polymer, lipid, cross-linked protein, lipid–polymer complex, lipid–protein complex, and membrane with transport carriers.

3. Surface properties of artificial cell membrane can be varied by: (1) incorporation of negative or positive charge; (2) incorporation of albumin to increase blood compatibility; (3) incorporation of antigens to bind antibodies or antibodies to bind antigen; (4) incorporation of polysaccharide such as heparin or polyethylene glycol (PEG) to increase compatibility or retention time in circulation.

4. In addition to being of cellular dimensions in the micron range, they can also be in the macro range, in the nano range or in the nanobiotechnological range (Figure II.5.4.1).

5. The artificial cell membranes can be ultrathin and yet strong. There is a large surface area to volume relationship. For example, 10 ml of 20 μm diameter artificial cells has a total surface area of 2500 cm2, which is the same as that in an artificial kidney machine. Since the artificial cell membrane is also 100 times thinner, permeant molecules can potentially move across 10 ml of 20 μm diameter artificial cells 100 times faster than across the artificial kidney machine (Chang, 1966). In addition, the microscopic size of artificial cells allows material to diffuse rapidly inside the artificial cells.

FIGURE II.5.4.1 Upper: Basic principle of early artificial cells. Center: Different types of early artificial cells based on this basic principle. Lower: Present status of artificial cells with wide variations in contents, membrane material, and dimensions.

(Figure from Chang (2007), Monograph with permission from World Scientific Publisher.)

Research into the Applications of Artificial Cells

This includes hemoperfusion, immunosorbents, drug delivery, blood substitutes, enzyme therapy, cell and stem cell therapy, biotechnology and nanobiotechnology, nanomedicine, regenerative medicine, agriculture, industry, aquatic culture, nanocomputers, nanorobotics, nanosensors, and other areas (Table II.5.4.1). The following is a brief overview of some examples of artificial cells.

TABLE II.5.4.1 Artificial Cell: Applications

Artificial Cells in Hemoperfusion

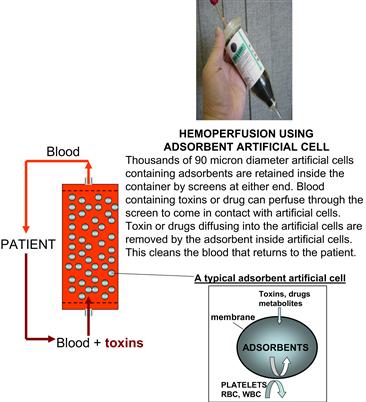

This is the first large-scale US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved routine clinical application in patients based on artificial cells. As mentioned above, the microscopic dimensions of artificial cells result in a large surface-to-volume relationship. This, together with the ultrathin membranes, allows artificial cells containing bioadsorbents to be much more effective when compared to standard hemodialysis in removing toxins and drugs from the blood of patients (Chang, 1966, 1969, 1972a, 1975, 2007; Chang et al., 1973). In this method, thousands of 90 micron diameter artificial cells containing adsorbents are retained by screens at either end, inside a column the size of a tea cup (Figure II.5.4.2). Blood from the patients containing toxins or drug can perfuse through the screens to come into contact with the artificial cells. Toxins or drugs diffusing into the artificial cells are removed by the adsorbents inside artificial cells. This cleanses the blood that returns to the patient.

FIGURE II.5.4.2 Upper right: A hemoperfusion device held in the hand. Left: Schematic representation of the hemoperfusion device. Right: Schematic representation of an artificial cell containing adsorbent.

(Figure from Chang (2007), with copyright permission from World Scientific Publisher.)

Routine Clinical Uses in Patients with Suicidal Drug Overdose

The most common routine use of this approach is the use of microscopic polymeric artificial cells encapsulating activated charcoal (Chang, 1969, 1975, 2007; Chang et al., 1973) (Figure II.5.4.2). This solves the major problems of release of embolizing particles and damage to blood cells when bioadsorbents are used without artificial cell membranes. This was first successfully used in suicidal overdose patients (Chang et al., 1973) (Figure II.5.4.3). Since then, this has been become a routine treatment worldwide for acute poisoning in adults and children, especially in suicidal overdose (Chang, 1975; Chang et al., 1973; Winchester, 1996; Kawasaki et al., 2000; Lopez Lago et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2002, 2004; Singh et al., 2004; Peng et al., 2004). This is particularly useful in places where dialysis machines are not easily available, and the hemoperfusion devices are less costly, especially outside North America. Hemoperfusion has saved the lives of thousands of suicidal drug overdose patients in some countries outside North America.

FIGURE II.5.4.3 Clinical and laboratory results of hemoperfusion in a patient with severe suicidal methyprylon overdose.

(Figure from Chang (2007), with copyright permission from World Scientific Publisher.)

Immunosorbents

The success in the clinical uses of artificial cells containing bioadsorbents for detoxification has led to increasing interest in research and development in many other areas. One of these is in artificial cells containing immunoadsorbents (Chang, 1980).

Albumin can bind tightly to the ultrathin collodion membrane of adsorbent artificial cells (Chang, 1969). This was initially used to increase the blood compatibility of the adsorbent artificial cells for hemoperfusion (Chang, 1969). We also applied this albumin coating to synthetic immunosorbents resulting in blood compatible synthetic blood group immunoadsorbents (Chang, 1980). This albumin-coated synthetic adsorbent has been applied clinically for removing blood group antibodies from plasma for bone marrow transplantation (Bensinger et al., 1981). In addition, albumin-coated collodion activated charcoal (ACAC) was found to effectively remove antibodies to albumin in animal studies (Terman et al., 1977). This has become the basis of one line of research in which other types of antigens or antibodies are applied to the collodion coating of the activated charcoal to form immunoadsorbents. Other immunoadsorbents based on this principle have also been developed for the treatment of human systemic lupus erythrematosus, removal of antiHLA antibodies in transplant candidates, treatment of familial hypercholesterolemia with monoclonal antibodies to low-density lipoproteins, and other conditions (Terman et al., 1979; Hakim et al., 1990; Wingard et al., 1991; Yang et al., 2004).

Nanobiotechnology for Partial Artificial Red Blood Cells

There is much recent interest in nanobiotechnology and nanomedicine. This is a large and complex area that embraces many diverse approaches. One of these is to make the original artificial cells smaller, using the same basic principle and methods. This includes biodegradable nanoparticles, nanosphere, and nanocapsules. Examples include nano-artificial red blood cells with lipid membrane or biodegradable polymeric membranes. A later section will summarize other examples used in drug delivery systems. Much smaller nanobiotechnological complexes can be prepared by the assembling of biological molecules. Examples include the assembling of hemoglobin molecules into soluble polyhemoglobin, and the assembling of hemoglobin molecules and enzymes into soluble polyhemoglobin–enzyme complexes.

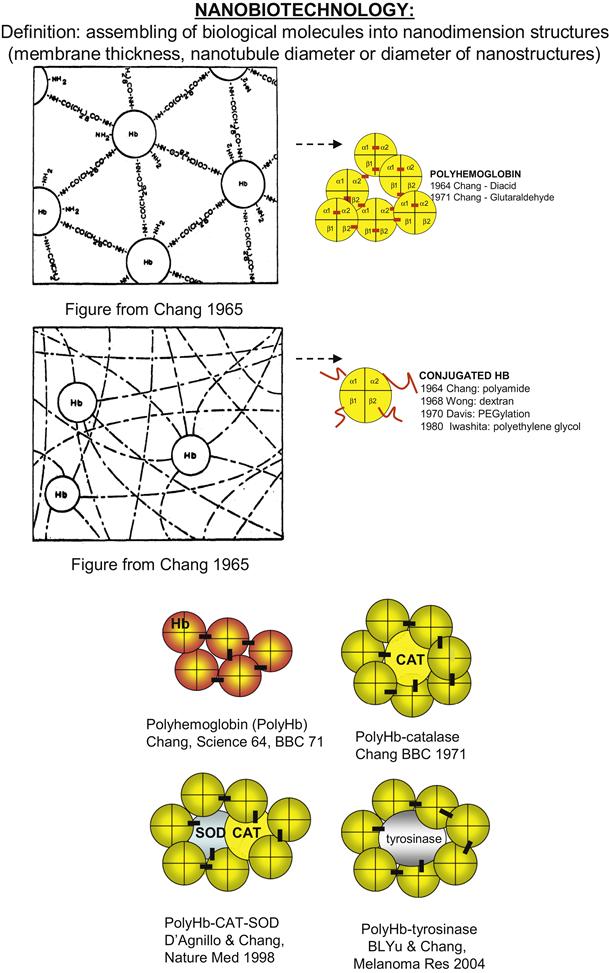

Nanobiotechnology and Artificial Cells

Nanobiotechnology is the assembling of biological molecules into nanodimension complexes of different configurations. These include nanostructures with nano-range diameters, membranes with nanodimension thickness or nanotubules with nanodimension diameters.

The first nanobiotechnology approach reported is the cross-linking of hemoglobin into an ultrathin polyhemoglobin (PolyHb) membrane with nanodimension thickness (Chang, 1964, 1965) (Figure II.5.4.4). This is used to form the membrane of artificial red blood cells (Chang, 1964, 1965, 1972a). If the emulsion is made very small, then the whole submicron artificial cells can be cross-linked into PolyHb of nanodimension. Glutaraldehyde can cross-link hemoglobin into soluble PolyHb of nanodimension, each consisting of an assembly of 4–5 hemoglobin molecules (Chang 1972b; Keipert and Chang, 1985, 1987) (Figure II.5.4.4).

FIGURE II.5.4.4 Nanoartificial cells can be prepared in the nanodimensions as membrane enclosed nanoartificial cells or by the use of nanobiotechnology to assemble biological molecules together into nanodimension structures. Upper: An example of assembling of biological molecules to form PolyHb and conjugated Hb. Lower: Examples of different types of nanobiotechnology based PolyHb-enzymes.

(Figure from Chang (2007), with copyright permissions from World Scientific Publisher.)

Two groups have independently developed this 1971 (Chang, 1971b) basic method of glutaraldehyde cross-linking for clinical use. One is glutaraldehyde human PolyHb (PolyHb) (Gould et al., 1998, 2002). Their phase III clinical trial shows that this can replace blood lost in trauma surgery by keeping the blood hemoglobin at an acceptable level. More recently they have carried out clinical trials in prehospital ambulance patients (Moore et al., 2009). The second PolyHb is glutaraldehyde-cross-linked bovine PolyHb which has been tested in phase III clinical trials (Pearce and Gawryl, 1998; Sprung et al., 2002; Pearce et al., 2006; Jahr et al., 2008). South Africa has approved this for routine clinical use in patients. Unlike red blood cells, there is no blood group in PolyHb, and thus PolyHb can be given on the spot, without waiting for typing and cross-matching in the hospital. PolyHb is also free from infective agents such as HIV, hepatitis C, bacteria, parasites, and so on. Furthermore, whereas donor blood has to be stored at 4°C and is only good for 42 days, PolyHb can be stored at room temperature for more than one year. Thus, PolyHb can have important uses in a number of clinical conditions, notably for surgery when there is no potential for ischemia-reperfusion, as will be discussed below (Chang, 2006a, 2009).

Nanobiotechnology and the Assembling of Hemoglobin with Antioxidant Enzyme

As PolyHb can be kept at room temperature and used immediately, it can have potential for treating severe bleeding (hemorrhagic shock). However, this has to be done as soon as possible, since if there is much delay PolyHb alone might result in the production of oxygen radicals that cause tissue injury (ischemia-reperfusion injuries). Antioxidant enzymes normally present in red blood cells are insufficient to prevent this problem. We use glutaraldehyde cross-linking to assemble a soluble nanobiotechnology complex by cross-linking hemoglobin, superoxide dismutase, and catalase into PolyHb-SOD-CAT (D’Agnillo and Chang, 1998; Chang 2006b, 2007, 2008) (Figure II.5.4.4). This way, one can increase the antioxidant enzymes to much higher levels than those in red blood cells.

Obstruction of arteries due to clots or other causes can result in stroke (cerebral ischemia) or heart attack (myocardial infarction). As it is a solution, PolyHb can more easily perfuse partially obstructed vessels. However, if there is prolonged lack of oxygen, reperfusion with PolyHb alone may result in damaging oxygen radicals resulting in ischemia-reperfusion injuries. Thus, in patients with coronary heart disease and myocardial ischemia, infusion with polyhemoglobin can result in ischemia-reperfusion injury that can be severe enough to result in heart attack (myocardial infarction). In severe trauma, one is often faced with hemorrhagic shock from severe bleeding, in addition to cerebral ischemia due to head injuries. In a hemorrhagic shock and stroke rat model, after 60 minutes of ischemia, reperfusion with PolyHb resulted in significant increase in the breakdown of the blood–brain barrier, and an increase in brain water (brain edema) (Powanda and Chang, 2002). On the other hand, PolyHb-SOD-CAT did not result in these adverse changes (Powanda and Chang, 2002). In sustained hemorrhagic shock due to severe loss of blood, ischemia-reperfusion can result in irreversible shock due to leakage of bacteria and endotoxins from the intestine into the circulating blood. Our study shows that in an ischemia-reperfusion rat inestinal model, polyhemoglobin resulted in significant increases in oxygen radicals. On the other hand, the use of PolyHb-SOD-CAT did not result in any significant increases in oxygen radicals (Razack et al., 1997; Chang, 2007).

Nanobiotechnology for the Assembling of Hemoglobin with Other Enzymes

The microcirculation structure in tumors is abnormal, and as a result there is a decrease in perfusion by oxygen carrying red blood cells. This results in a lower oxygen tension in the tissue of many types of tumors (Pearce and Gawryl, 1998). It is known that radiation therapy and some chemotherapy can work better when the tissue oxygen tension is higher. PolyHb can more easily perfuse the abnormal microcirculation of tumors to supply oxygen needed for chemotherapy or radiation therapy. With a circulation half-time of 24 hours, the effect is not long-term and can be adjusted to the duration of chemotherapy or radiation therapy. When used together with chemotherapy, PolyHb decreases tumor growth and increases the lifespan in a rat model of gliosarcoma brain tumor (Pearce and Gawryl, 1998). We have recently cross-linked tyrosinase with hemoglobin to form a soluble PolyHb-tyrosinase complex (Yu and Chang, 2004) (Figure II.5.4.4). This has the dual function of supplying the needed oxygen, and at the same time lowering the systemic levels of tyrosine needed for the growth of melanoma. Intravenous injections delayed the growth of the melanoma without causing adverse effects in the treated animals (Yu and Chang, 2004).

Polyhemoglobin-Fibrinogen

Blood is a multifunctional fluid. As a blood substitute, PolyHb is limited by its lack of platelets and/or coagulation properties. In situations of high blood volume loss, large volumes of PolyHb have to be infused to replace the lost blood. Replacing the loss of red blood cells without replacing the lost platelets and coagulation factors can result in the inability of the blood at the injured sites to clot, resulting in continued severe bleeding. As a result, platelets and coagulation factors have to be infused in these situations. Unfortunately, donor platelets are very hard to obtain. There has been development in platelet substitutes to combat thrombocytopenia, but with limited success. We therefore prepared a novel blood substitute that is an oxygen carrier with platelet-like activity. This is formed by cross-linking fibrinogen to hemoglobin to form polyhemoglobin-fibrinogen (PolyHb-Fg) (Wong and Chang, 2007). This was studied and compared to PolyHb for its effect on coagulation, both in vitro and in vivo. In the in vitro experiments PolyHb-Fg showed similar clotting times as whole blood, whereas PolyHb showed significantly higher clotting times. This result was confirmed in in vivo experiments using an exchange transfusion rat model. Using PolyHb, exchange transfusion of 80% or more increased the normal clotting time (1–2 mins) to >10 minutes. Partial clots formed with PolyHb did not adhere to the tubing wall. With PolyHb-Fg, a normal clotting time (1–2 mins) is maintained even with 98% exchange transfusion.

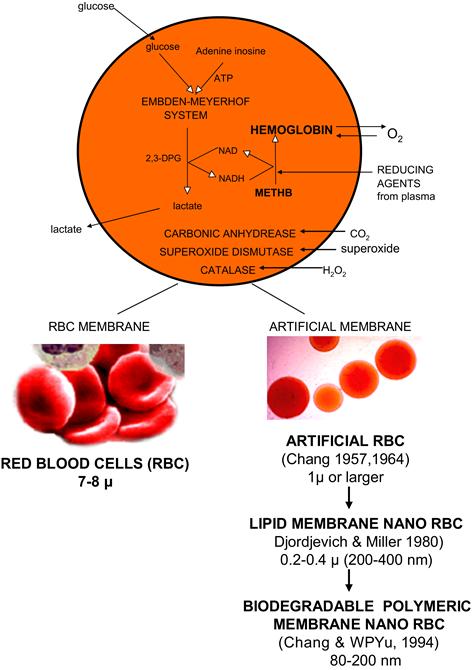

Nanobiotechnology for Complete Artificial Red Blood Cells

Original Micron Dimension Complete Artificial Red Blood Cells

The first artificial red blood cells (RBCs) prepared in 1957 (Chang, 1957) have an oxygen dissociation curve similar to red blood cells. We continued to study a number of artificial cell membranes including cellulose, silicone rubber, 1,6-hexamethylenediamine, cross-linked protein, phospholipid–cholesterol complexes on cross-linked protein membrane or polymer (Chang, 1964, 1965, 1972a). However, these artificial RBCs, even with a diameter down to one micron, survived for a short time in the circulation after intravenous injection. Our study showed that the long circulation time of RBCs is due to the presence of neuraminic acid on the membrane (Chang, 1965, 1972a). This led us to study the effects of changing surface properties of the artificial RBCs (Chang, 1964, 1965, 1972a). This has resulted in significant increases in circulation time, but is still insufficient for clinical use.

Submicron Hemoglobin Lipid Vesicles as Artificial Red Blood Cells

We prepared larger artificial cells with lipid membrane by supporting the lipid in the form of lipid–protein membrane and lipid–polymer membrane (Chang, 1972a). Others later reported the preparation of submicron (0.2 micron) diameter artificial RBCs using lipid membrane vesicles to encapsulate Hb (Djordjevich and Miller, 1980). This increased the circulation time significantly, although it was still rather short. Many investigators have since carried out research to improve the preparation and circulation time. The most successful approach to improve the circulation time is to incorporate polyethylene glycol (PEG) into the lipid membrane of artificial RBCs, resulting in a circulation half-time of more than 30 hours (Philips et al., 1999). Another group in Japan has for many years carried out extensive research and development, commercial development, and preclinical animal studies. Their extensive studies are available in many publications and reviews (Kobayashi et al., 1997; Sakai et al., 2004; Tsuchida, 1998).

Biodegradable Polymeric Nanodimension Completely Artificial Red Blood Cells

We have used a biodegradable polymer, polylactic acid (PLA), for the microencapsulation of Hb, enzymes, and other biologically active material since 1976 (Chang, 1976). More recently, we started to prepare artificial RBCs of 100 nanometer mean diameter using PLA, PEG–PLA membrane, and other biodegradable polymers (Yu and Chang, 1994, 1996; Chang, 1997a, 2006c, 2007; Chang et al., 2003). A typical electron micrograph for the biodegradable polymer Hb nanocapsules prepared with d,l-PLA shows that they are spherical and homogeneous. Their diameter ranges from 40–120 nm, with a mean diameter of 80 nm. The membrane thickness is 5–15 nm. We have replaced most of the 6 g/dl of lipid membrane in Hb lipid vesicles with 1.6 g/dl of biodegradable polymeric membrane material (Figures II.5.4.5 and II.5.4.6). This marked decrease in the lipid component would lessen the effects on the reticuloendothelial system (RES), and lessen lipid peroxidation in ischemia-reperfusion.

We can increase the Hb content in the PLA nano-artificial cell suspension from 3 g/dl to 15 g/dl (the same as whole blood). This has normal P50, Hill’s coefficient, and Bohr coefficient. Nanocapsules can be prepared with up to 15 g/dl Hb concentration. The preparation of PLA nano-artificial RBCs does not have adverse effects on the Hb molecules. This is shown by the following experimental results. There is no significant difference in the oxygen affinity (P50) of Hb nano-artificial RBC and the original Hb used for the preparation, the Hill coefficient is 2.4 to 2.9 and the Bohr effect is −0.22 to −0.24 (Yu and Chang, 1994, 1996; Chang, 1997a, 2006c, 2007; Chang et al., 2003).

We have earlier carried out basic research on artificial cells containing multienzyme systems with cofactor recycling (Chang, 1987). A number of enzymes such as carbonic anhydrase, catalase, superoxide dismutase and the MetHb reductase system, normally present in RBC have been encapsulated within nano-artificial RBC and retain their activities (Figure II.5.4.5) (Chang et al., 2003; Chang, 2007). Unlike lipid membrane, biodegradable polymeric membrane is permeable to glucose. Thus, the inclusion of an RBC MetHb reductase enzyme system prevents MetHb formation even at 37°C, and we can also convert MetHb to Hb at 37°C. In addition, unlike lipid membrane, the nanocapsule membrane allows plasma factors such as ascorbic acid to enter the nanocapsules to prevent MetHb formation (Figure II.5.4.5).

FIGURE II.5.4.5 Upper: Composition of red blood cell and artificial red blood cells. Lower Left: Red blood cells. Lower Right: First artificial RBC of 1 micron or larger diameter, first lipid membrane nanodimension artificial RBC, first nanodimension biodegradable polymeric membrane artificial RBC.

(Figure from Chang (2007), with copyright permissions from World Scientific Publisher.)

FIGURE II.5.4.6 Top: Amount of membrane material in hemoglobin lipid vesicles compared to polylactide membrane nano RBC. Bottom: Fate of polylactide membrane in PLA nano RBC compared to PLA metabolism in the body.

(Figure from Chang (2007), with copyright permission from World Scientific Publisher.)

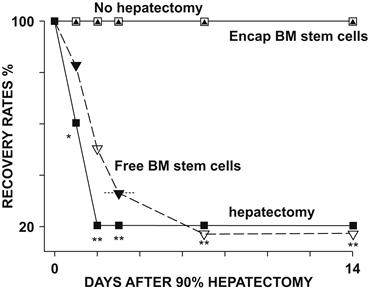

FIGURE II.5.4.7 Survival rates of rats with 90% of liver surgically removed, hepatectomy, compared to those without removal of liver tissues, no hepatectomy. One peritoneal injection of artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells resulted in the survival of the 90% hepatectomized rats. On the other hand, free bone marrow stem cells did not significantly increase the survival rates (Liu and Chang, 2006).

(Figure from Chang (2007), with permission from World Scienctific Publisher.)

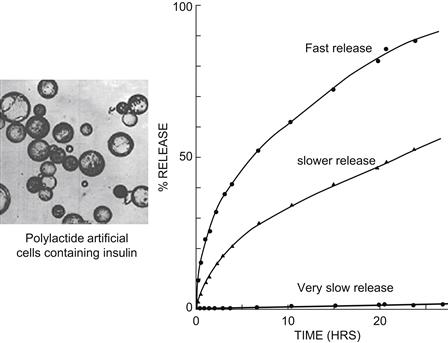

FIGURE II.5.4.8 Biodegradable membrane artificial cells have been prepared to contain enzymes, hormones, vaccines, and other biologicals (Chang, 1976). This figure summarizes the result of polylactide artificial cells prepared by double emulsion method. Variations in the molecular weight of polylactide and the thickness of the membrane can result in artificial cells that release insulin at different rates. Faster release comes from the encapsulation of insulin solution at high concentration. Very slow release comes from the encapsulation of insulin crystals (Chang, 1976).

(Figure from Chang (2007), with copyright permission of World Scientific Publisher.)

In order to increase the circulation time, we synthesized a new PEG–PLA copolymer for the artificial RBC membrane (Chang et al., 2003). After a 30% blood volume toploading using PolyHb (10 g/dl), the best PolyHb can only attain a maximal Hb concentration of 3.35 g/dl. The best PEG–PLA nano-artificial RBC, on the other hand, can reach a maximal Hb concentration of 3.60 g/dl. After extensive research, we now have a circulation time in rats that is double that of glutaraldehye cross-linked PolyHb. Since the RES in rat is much more efficient in removing particulate matter compared to humans, it is likely that the half-time would be longer in humans. Recent long-term studies in rats show no adverse effects in the kidney and the reticuloendothelial systems (liver and spleen) (Liu and Chang, 2008).

Cells, Islets, Stem Cells, Genetically Engineered Cells, and Microorganisms

Introduction

The first artificial cells containing intact biological cells were reported in 1964 based on a drop method (Chang, 1964), and it was proposed that: “protected from immunological process, encapsulated endocrine cells might survive and maintain an effective supply of hormone” (Chang et al., 1966) (Figure II.5.4.1).

Artificial Cells Containing Islets, Hepatocytes, and Other Cells

With Chang’s encouragement and initial consultation, Sun from Conaught Laboratory and his collaborator developed Chang’s original drop method (Chang, 1964, 1965, 1972a; Chang et al., 1966) by changing to alginate-polylysine-alginate (APA) as the artificial cell membrane (Lim and Sun, 1980). They showed that after implantation, the insulin secreting islets inside artificial cells indeed remained viable and continued to secrete insulin to control the glucose levels of diabetic rats (Lim and Sun, 1980; Sun et al., 1996). Extensive research has been carried out by many laboratories around the world since that time and is available in reviews (Calafiore, 1999; De Vos et al., 2002; Orive et al., 2003, 2004; Hunkeler, 2003; Chang, 2005a,b, 2007). The major hurdle is the need for long-term function after implantation.

We have been studying the use of artificial cells containing liver cells (hepatocytes) for liver support. Implanting these increases the survival of acute liver failure rats (Wong and Chang, 1986); lowers the high bilirubin level in congenital Gunn rats (Bruni and Chang, 1989); and prevents xenograft rejection (Wong and Chang, 1988). We developed a two-step cell encapsulation method to improve the APA method, resulting in improved survival of implanted cells (Wong and Chang, 1991). Artificial cells containing hepatocytes effectively lower the systemic bilirubin in hyperbilirubinemia Gunn rats (Bruni and Chang, 1989, 1995). We used the two-step method plus the co-encapsulation of stem cells and hepatocytes into artificial cells (Liu and Chang, 2000). This results in further increases in the viability of encapsulated hepatocytes, both in culture and after implantation (Liu and Chang, 2002). One implantation of artificial cells containing both hepatocytes and stem cells into Gunn rats lowers the systemic bilirubin levels and maintains this low level for two months (Liu and Chang, 2003). Without stem cells, implanted hepatocytes in artificial cells can only maintain a low level for one month.

Genetically Engineered Cells and Microorganisms

Many groups have carried out extensive research on artificial cells containing genetically engineered cells. This is a very important area which includes potential applications in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Dwarfism, pain treatment, IgG1 plasmacytosis, Hemophilia B, Parkinsonism and axotomized septal cholinergic neurons, tumor suppression, and other areas (Winn et al., 1994; Saitoh et al., 1995; Aebischer et al., 1996; Al-Hendy et al., 1996; Basic et al., 1996; Tan et al., 1996; Hagihara et al., 1997; Dalle et al., 1999; Bachoud-Lévi et al., 2000; Lorh et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2002; Cirone et al., 2002; Bloch et al., 2004). To avoid the need for implantation, we studied the oral use of artificial cells containing microorganisms for the removal of cholesterol (Garofalo and Chang, 1991) or conversion of phenol to tyrosine (Lloyd-George and Chang, 1995). We have also studied the use of genetically engineered nonpathogenic E. coli DH5 cells to lower systemic urea in renal failure rats (Prakash and Chang, 1993, 1996; Chang, 1997b, 2005a,b). Genetically engineered E. coli allows for proof of principle. For safe use, we have studied the use of a modified Lactobacillus, similar to those used in yoghurt, for enclosure in artificial cells to remove urea (Chow et al., 2003).

General

Cell bioencapsulation for cell therapy has been extensively developed by many groups, especially using artificial cells containing endocrine tissues, hepatocytes, genetically engineered cells, and stem cells (Chang, 1972a; Orive et al., 2003; Chang, 2005a,b, 2007). The major hurdle is the need to develop systems that can function on a long-term basis after implantation.

Artificial Cells Containing Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine

The above examples of artificial cells containing islets, cells, genetically engineered cells, and other cells require long-term treatment. Developments are needed before artificial cells are ready for long-term implantation use. To allow for more immediate use, one area of research in this laboratory is to look at the use of artificial cells in regenerative medicine. For this we have been studying the use of artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells for liver regeneration. Marked decrease in liver function due to fulminant hepatic failure or extensive liver resection for metastatic cancer or severe injury can result in the death of the patient. Since liver can regenerate if given the required time and conditions, we therefore studied whether artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells can maintain the experimental animal alive long enough to allow the liver to regenerate and the animal to recover (Figure II.5.4.7).

Artificial Cells Containing Bone Marrow Stem Cells in 90% Hepatectomized Rats

In the present study we injected intraperitoneally artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells into 90% hepatectomized rats (Liu and Chang, 2005, 2006) (Figure II.5.4.7). In the hepatectomized groups that received no treatment, only 20% of the animals survived by the second day. In the hepatectomized animals receiving free bone marrow stem cells, only 20% of the animals survived on the seventh day. There was no significant difference in survival rate between the normal control group (with no hepatectomy) and the group receiving artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells. The survival for both groups was 100% when followed for 14 days. Thus it would appear that in rats, artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells are effective in improving the survival rates of 90% hepatectomized rats. For those rats that survived at week 2 post hepatectomy, the remnant livers were removed and the weights were measured. In the 90% hepatectomized rats that received artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells, the liver wet weights had recovered to the same size as that of the normal control group (Liu and Chang, 2006). On the other hand, those few animals in the other groups that survived had very low liver weights.

Plasma Hepatic Growth Factor (HGF) Levels

In the hepatectomized groups that received artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells, the blood levels of HGF peaked at day 2 and 3 post-surgery, and were significantly higher than the other groups (Liu and Chang, 2006). After this, the levels decreased and returned to pre-surgery levels on day 14. In the hepatectomized groups that received: (1) no treatment; or (2) free bone marrow stem cells, the blood HGF levels were much lower.

Laparotomy, Histology, and Immunocytochemistry

Two weeks after implantation, laparotomy shows that in the group that received artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells, the artificial cells remained in the peritoneal cavity. They were found freely disseminated throughout the peritoneal cavity, aggregated behind the liver or under the spleen, or attached to the large omentum. Histological examination of bone marrow stem cells in the artificial cells showed that before transplantation most cells were polygonal, star-like, some with tail shaped cytoplasm. When they were retrieved two weeks after transplantation, most cell morphology transformed to round or oval (Liu and Chang, 2006).

Before implantation, the bone marrow stem cells recovered from artificial cells did not show positive immunochemistry stain. However, when bone marrow stem cells were recovered from artificial cells at week 2 after implantation, there were scattered cells positively stained with hepatocyte markers CK8 and CK18, and also albumin production. There were also cells that stained positively with AFP (Liu and Chang, 2006). In the bone marrow stem cells recovered from artificial cells retrieved 2 weeks post-transplantation, there were cells stained positive for PAS, indicating that there were also cells capable of glycogen production.

Possible Mechanisms Responsible for the Recovery of 90% Hepatectomized Rat Model

What are the mechanisms responsible for the survival and recovery of the 90% hepatectomized rat model in our present study? Most likely this is due to two combined mechanisms (Chang, 2007).

1. Transdifferentiation of bone marrow stem cells in the artificial cells into hepatocytes. This is supported by our immunochemistry stain studies which show that some of the bone marrow stem cells recovered from artificial cells transdifferentiated into hepatocyte-like cells that expressed ALB, CK8, CK18, and AFP, which are typical markers of hepatocytes. They also produced albumin and glycogen. However, this is a slow process that takes time, and is most likely only responsible for the later phases of the recovery of the animals.

2. Hepatic growth factor (HGF) is an important factor in liver regeneration (Rokstad et al., 2002) and also in stimulating the transdifferentiation of bone marrow cells into hepatocytes (Spangrude et al., 1988). There are two subgroups of HGF, one >100,000 Da the other <10,000 Da (Michalopoulos et al., 1984). Alginate-polylysine-alginate membrane artificial cells allow the passage of molecules of 64,000 Da or less, and retain those >64,000 Da (Ito and Chang, 1992). HGF of >100,000 mw secreted by hepatocytes are retained and accumulated in the artificial cells, thus helping to increase the regeneration of hepatocytes in the artificial cells (Kashani and Chang, 1988, 1991) and also the transdifferentiation of BMCs. The smaller molecule weight HGF of <10,000 can diffuse out of the artificial cells to stimulate the regeneration of the remaining 10% liver mass in the 90% hepatectomized rats. Thus, the 90% hepatectomized rats that received artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells had significantly higher blood HGF levels than the other groups. Our result shows that artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells stayed in the peritoneal cavity throughout the 14 days of the study. This way, HGF secreted can be drained into the portal circulation to reach the 10% remaining liver mass to stimulate its regeneration. On the other hand, intraperitoneal injection of free bone marrow stem cells did not increase survival rates. Most likely this is because the free bone marrow stem cells are rapidly removed from the peritoneal cavity through the lymphatic drainage, and any HGF released does not drain into the portal circulation to have the most effective stimulating effect on the remnant liver.

Artificial Cells Containing Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine

It would appear from the above study that implantation of artificial cells containing bone marrow stem cells results in the regeneration of the 90% hepatectomized liver, and the survival of the animal. These observations could stimulate further investigation of the potential for the treatment of acute liver failure or extensive liver resection to allow the liver to regenerate. The use of artificial cells containing stem cells could also be investigated in other areas of regeneration medicine.

Gene and Enzyme Therapy

Artificial cells have been studied for use in gene and enzyme therapy (Chang, 1964, 1972a, 2005a, 2007). The enclosed enzyme would not leak out, but could act on external permeant substrates. This would avoid protein sensitization, anaphylactic reaction or antibody production with repeated injection (Figure II.5.4.1). Implanted urease artificial cells convert systemic urea into ammonia (Chang, 1964, 1965). Implanting artificial cells containing catalase replaces the defective enzyme in mice with a congenital defect in catalase – acatalasemia (Chang and Poznansky, 1968). The artificial cells protect the enclosed enzyme from immunological reactions (Poznansky and Chang, 1974). Artificial cells containing asparaginase implanted into mice delay the onset and growth of lymphosarcoma (Chang, 1971b).

Giving enzyme artificial cells by mouth avoids the need for repeated injection. For example, artificial cells containing urease and ammonia adsorbent can lower the systemic urea level (Chang, 1972a). In Lesch-Nyhan disease, enzyme defect results in the elevation of hypoxanthine to toxic levels. Given by mouth, artificial cells containing xanthine oxidase lower the toxic systemic hypoxanthine levels in an infant with this disease (Chang, 1989; Palmour et al., 1989). Phenylketonuria is a more common congenital enzyme defect. Artificial cells containing phenylalanine ammonia lyase given by mouth lower the systemic phenylalanine levels in phenylketonuria (PKU) rats (Bourget and Chang, 1985, 1986). This has led to investigation into recombinant sources of this enzyme (Safos and Chang, 1995; Sarkissian et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2002) that are now being tested in clinical trials.

Multienzyme Systems with Cofactor Recycling

Most enzymes in the body function as multienzyme systems with cofactor recycling. After basic research on artificial cells containing multienzyme systems (Campbell and Chang, 1976; Cousineau and Chang, 1977; Yu and Chang, 1982; Chang 1985; Ilan and Chang, 1986) we looked into their possible use. Thus, artificial cells containing three different enzymes can convert metabolic waste such as urea and ammonia into essential amino acids (Gu and Chang, 1988, 1990). The needed cofactor, NADH, can be recycled and retained inside the artificial cell by cross-linking to dextran or by the use of a lipid–polymer membrane. As discussed earlier, under artificial red blood cells, all the multienzyme system in red blood cells can be incuded inside nanodimensional artificial red blood cells (Chang, 2007; Chang et al., 2003) (Figure II.5.4.5).

Drug Delivery

Gene and enzyme therapy is a form of drug delivery using artificial cells. However, the genes and enzymes are retained inside the artificial cells at all times, and act on substrates diffusing into the artificial cells. Artificial cells in different modified forms have also been used in drug delivery. However, these are used to separate the drug from the external environment, and to release the drug at a specific site and a specific rate when and where it is needed. Drug delivery is an extremely large and wide area, and many excellent reviews and books are available. In this chapter, only artificial cell-related systems will be very briefly summarized.

Polymeric Membrane Artificial Cells of Microscopic Dimensions

Luzzi (1970) used nylon membrane artificial cells, microcapsules, prepared as reported (Chang, 1964), to microencapsulate drugs for slow release for oral administration. Others have also extended this approach. However, the modern approaches in drug delivery systems are based on injectable biodegradable systems.

Biodegradable Polymeric Artificial Cells (Microparticles, Nanoparticles, Microcapsules, Nanocapsules)

Biodegradable polylactide membrane artificial cells have been prepared to contain enzymes, hormones, vaccines, and other biologicals (Chang, 1976). The polylactide polymer can degrade in the body into lactic acid, and finally into water and carbon dioxide. Variations in preparation can result in artificial cells that release insulin at different rates (Chang, 1976) (Figure II.5.4.8).

We have also used these for the slow release of prostaglandin E2 (Zhou and Chang, 1988) and ciprofloxacin (Yu et al., 1998, 2000). Biodegradable drug delivery systems are now used widely in different forms, ranging from microscopic to nanodimensions. They are also known as nanoparticles, nanocapsules, polymersomes, nanotubules, etc. Langer’s group has written an excellent review on this topic (LaVan et al., 2002). Copolymers of polyethylene glycol (PEG) and polylactic acid (PLA) have been used to increase the circulation time of nanodimensional artificial cells. As described earlier in this chapter, this also forms the basis for preparing nanodimension PEG–PLA membrane artificial red blood cells (Yu and Chang, 1996; Chang et al., 2003; Chang, 2005a, 2006a).

Liposomes Evolved into Lipid Membrane Artificial Cells and Then Back into Polymeric Membrane Artificial Cells

Bangham (1965) reported the preparation of liposomes each consisting of microspheres of hundreds of concentric lipid bilayers – multi-lamellar. This was initially used as membrane models in basic research. Gregoriadis (1976) first reported the use of liposomes as drug delivery systems. However, the large amount of lipid in the multi-lamellar liposome limits the amount of water-soluble drugs that can be enclosed. Thus, the basic principle and method of preparing artificial cells using ether as the dispersing phase (Chang, 1957, 1964) was extended by researchers into what they call an “ether evaporation method” to form single bilayer (unilamellar) lipid membrane liposomes (Deamer and Bangham, 1976). These lipid membrane artificial cells have since been extensively studied for use as drug delivery systems (Torchilin, 2005). Surface charges have also been incorporated into liposomes for possible targeting of drug, and more recently the use of positively charged lipid to complex with DNA. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) has also been incorporated to the liposome surface to result in longer circulation time. Thus, lipid vesicles are becoming more like the lipid–polymer membrane artificial cells (Chang, 1972a), and are no longer pure lipid vesicles. Further development led to the incorporation of antibodies into the lipid membrane, to allow for targeting to cells with the corresponding antigens. The principle of loading magnetic particles into artificial cells (Chang, 1966) has also been used for loading into liposome, allowing for magnetic targeting. One major advantage of lipid vesicles is in their ability to fuse with cellular membrane or membranes of intracellular organelles. This allows for much versatility in their ability to deliver drugs to different sites of the cells. A number of drugs in PEG–lipid vesicles have already been approved for clinical use or are in clinical trial (Torchilin, 2005). Discher’s group (Discher et al., 1999; Photos et al., 2003) tried to increase the strength of the PEG–lipid membrane artificial cells by using self-assembling of copolymer to form a membrane of PEG polymer. This significantly increased the circulation time and strength when compared to PEG–lipid membrane artificial cells Thus, multilamellar liposome has evolved into lipid membrane artificial cells, then polymer(PEG)–lipid membrane artificial cells, and finally back to the original polymeric membrane artificial cells (Chang, 1964) now called polymersomes.

Other Areas of Artificial Cells

Artificial Cells Containing Magnetic Materials

When magnetic material is included in artificial cells (ACs) containing bioactive materials, one can use an external magnetic field to direct the artificial cells (Chang, 1966). This way, the magnetic field can: (1) direct the movement of the AC; (2) remove the AC after reaction; (3) retain the AC at specific site of action; (4) stir or agitate the AC as in bioreactors. This principle is now being used very extensively in bioreactors, in removing specific materials from a mixture as in diagnositcs kits, in drug delivery systems, and in other areas of application.

Nanobiosensors

Nanobiosensors is an area that is of increasing interest, and different approaches are being investigated. One of the many approaches is to use a biosensor where a lipid bilayer is “tethered” on ultrathin polymeric support to form a lipid–polymer complex. In this form, different “channels” can be inserted into the membrane to allow for selective movement of specific solute for detection, somewhat similar to the principle reported earlier (Chang, 1969, 1972a; Rosenthal and Chang, 1971, 1980). Another approach that is also possible is to encapsulate enzymes inside artificial cells of microscopic or nanodimension. This way, the product of enzymatic reaction can be followed by fluorescence or other methods. The ability to prepare artificial cells with intracellular compartmentation (Chang, 1965, 1972a; Chang et al., 1966) would allow multi-step enzyme reaction to occur and be detected separately. Depending on the type of reaction being followed, one can use either polymeric membrane artificial cells, lipid membrane artificial cells or lipid–polymer membrane artificial cells.

Artificial Cells Containing Radioisotopes or Radio-Opaque Material

The general principle of artificial cells could be explored in many other areas. Thus, artificial cells containing radioactive isotopes or antimetabolites might be used for intra-arterial injection into tumors. In this case, some of the microcapsules might lodge at the tumor site, while others would be carried by lymphatic channels to metastases in regional lymph nodes. Artificial cells containing radio-opaque material would provide a contrast medium. Provided they can circulate readily in the bloodstream, they might be used as vehicles for contrast materials in angiography.

Nonmedical Uses of Artificial Cells

There are many developments and uses of the principle of artificial cells for agriculture, bioreactors, cosmetics, food production, aquatic culture, nanocomputers, and nanorobotics. However, these are not within the scope of this chapter.

The Future of Artificial Cells

The 1972 monograph Artificial Cells (Chang, 1972a) predicted that: “Artificial Cell is not a specific physical entity. It is an idea involving the preparation of artificial structures of cellular dimensions for possible replacement or supplement of deficient cell functions. It is clear that different approaches can be used to demonstrate this idea.” This prediction is already out of date since, in the last 50 years (Chang, 1957), artificial cells have progressed way beyond this 1972 prediction. Artificial cells can now be of macro-, micro-, nano-, and molecular dimensions. There are also unlimited possibilities in variations for artificial cell membranes and contents (Figure II.5.4.1). We have just touched the surface of the potential of artificial cells.

Acknowledgments

The ongoing support of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (whose original name was the Medical Research Council of Canada) over the last many years is gratefully acknowledged. Other support included the Quebec Hemovigillance and Transfusion Medicine Program under FRSQ.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Many of the references and books from the authors are available free from the McGill University public service website at www.artcell.mcgill.ca.

2. Aebischer P, Pochon NA, Heyd B, Déglon N, Joseph JM, et al. Gene therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) using a polymer encapsulated xenogenic cell line engineered to secrete hCNTF. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;1:851–860.

3. Al-Hendy A, Hortelano G, Tannenbaum GS, Chang PL. Growth retardation: An unexpected outcome from growth hormone gene therapy in normal mice with microencapsulated myoblasts. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:61–70.

4. Bachoud-Lévi AC, Déglon N, Nguyen JP, Bloch J, Bourdet C, et al. Neuroprotective gene therapy for Huntington’s disease using a polymer encapsulated BHK cell line engineered to secrete human CNTF. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:1723–1729.

5. Bangham AD. Diffusion of univalent ions across the lamellae of swollen phospholipids. J Mol Biol. 1965;13:238–252.

6. Basic D, Vacek I, Sun AM. Microencapsulation and transplantation of genetically engineered cells: A new approach to somatic gene therapy. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1996;24:219–255.

7. Bensinger W, Baker DA, Buckner CD, Clift RA, Thomas ED. Immunoadsorption for removal of A and B blood-group antibodies. New Engl J Med. 1981;314:160–162.

8. Bloch J, Bachoud-Lévi AC, Déglon N, Lefaucheur JP, Winkel L, et al. Neuroprotective gene therapy for Huntington’s disease, using polymer-encapsulated cells engineered to secrete human ciliary neurotrophic factor: Results of a phase I study. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:968–975.

9. Bourget L, Chang TM S. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase immobilized in semipermeable microcapsules for enzyme replacement in phenylketonuria. FEBS Lett. 1985;180:5–8.

10. Bourget L, Chang TM S. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase immobilized in microcapsules for the depleture of phenylalanine in plasma in phenylketonuric rat model. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;883:432–438.

11. Bruni S, Chang TM S. Hepatocytes immobilized by microencapsulation in artificial cells: Effects on hyperbiliru-binemia in Gunn rats. J Biomater Artif Cells Artif Organs. 1989;17:403–412.

12. Bruni S, Chang TM S. Kinetics of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase in bilirubin conjugation by encapsulated hepatocytes for transplantation into Gunn rats. J Artif Organs. 1995;19, 449–457.

13. Calafiore R. Transplantation of minimal volume microcapsules in diabetic high mammalians. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;875:219–232.

14. Campbell J, Chang TM S. The recycling of NAD+ (free and immobilized) within semipermeable aqueous microcapsules containing a multi-enzyme system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;69:562–569.

15. Chang EJ, Lee TH, Mun KC, Kim HC, Suh SI, et al. Effects of polyhemoglobin-antioxidant enzyme complex on ischemia-reperfusion in kidney. Transplant Proc. 2004a;36:1952–1954.

16. Chang EJ, Lee SH, Mun KC, Suh SI, Bae JH, et al. Effect of artificial cells on hepatic function after ischemia-reperfusion injury in liver. Transplant Proc. 2004b;36:1959–1961.

17. Chang TM S. Hemoglobin corpuscles Report of a research project for Honours Physiology, Medical Library, McGill University. Biomater Artif Cells Artif Organs. 1957;16:1–9 Also reprinted 1988 as part of “30th Anniversary in Artificial Red Blood Cells Research.”

18. Chang TM S. Semipermeable microcapsules. Science. 1964;146:524–525.

19. Chang TM S. Semipermeable Aqueous Microcapsules. McGill University 1965; Ph.D. thesis.

20. Chang TM S. Semipermeable aqueous microcapsules (“artificial cells”): With emphasis on experiments in an extracorporeal shunt system. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1966;12:13–19.

21. Chang TM S. Removal of endogenous and exogenous toxins by a microencapsulated absorbent. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1969;47:1043–1045.

22. Chang TM S. The in vivo effects of semipermeable microcapsules containing L-asparaginase on 6C3HED lymphosarcoma. Nature. 1971a;229:117–118.

23. Chang TM S. Stabilisation of enzymes by microencapsulation with a concentrated protein solution or by microencapsulation followed by cross-linking with glutaraldehyde. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971b;44:1531–1536.

24. Chang TM S. Artificial Cells. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1972a; out of print but available for free online viewing at www.artcell.mcgill.ca.

25. Chang TM S. Haemoperfusions over microencapsulated adsorbent in a patient with hepatic coma. Lancet. 1972b;2:1371–1372.

26. Chang TM S. Platelet–surface interaction: Effect of albumin coating or heparin complexing on thrombogenic surfaces. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1974;52:275–285.

27. Chang TM S. Microencapsulated adsorbent hemoperfusion for uremia, intoxication and hepatic failure. Kidney Int. 1975;7:S387–S392.

28. Chang TM S. Biodegradable semipermeable microcapsules containing enzymes, hormones, vaccines, and other biologicals. J Bioeng. 1976;1:25–32.

29. Chang TM S. Blood compatible coating of synthetic immunoadsorbents. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1980;26:546–549.

30. Chang TM S. Artificial cells with regenerating multienzyme systems. Meth Enzymol. 1985;112:195–203.

31. Chang TM S. Recycling of NAD(P) by multienzyme systems immobilised by microencapsulation in artificial cells. Meth Enzymol. 1987;136:67–82.

32. Chang TM S. Preparation and characterization of xanthine oxidase immobilized by microencapsulation in artificial cells for the removal of hypoxanthine. Biomater Artif Cells Artif Organs. 1989a;17:611–616.

33. Chang TM S. Red Blood Cell Substitutes: Principles, Methods, Products and Clinical Trials. Vol. I (Monograph) Basel, Switzerland: Karger/Landes Systems; 1997a; (Available for free online viewing at www.artcell.mcgill.ca or www.artificialcell.info.).

34. Chang TM S. Artificial cells. In: Renalo D, ed. Encyclopedia of Human Biology. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc.; 1997b;457–463.

35. Chang TM S. Bioencapsulated hepatocytes for experimental liver support. J Hepatol. 2001;34:148–149.

36. Chang TM S. Therapeutic applications of polymeric artificial cells. Nat Rev: Drug Discov. 2005a;4, 221–235.

37. Chang TM S. Methods for microencapsulation of enzymes and cells. Meth Biotechnol. 2005b;17:289–306.

38. Chang TM S. Blood substitutes based on bionanotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2006a;24:372–377.

39. Chang TM S. Polyhemoglobin-enzyme complexes. In: Winslow R, ed. Blood Substitutes. London, UK: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006b;451–459.

40. Chang TM S. PEG-PLA biodegradable hemoglobin nanocapsules as rbc substitutes. In: Winslow R, ed. Blood Substitutes. London, UK: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006c;523–531.

41. Chang TM S. Artificial Cells: Biotechnology, Nanotechnology, Blood Substitutes, Regenerative Medicine, Bioencapsulation, Cell/Stem Cell Therapy. Singapore and London: World Scientific Publisher/Imperial College Press; 2007; 435 pages.

42. Chang TM S. Nanobiotechnological modification of hemoglobin and enzymes from this laboratory. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: Proteins and Proteomics. 2008;1784 1435–1144.

43. Chang TM S. Nanobiotechnology for hemoglobin based blood substitutes. Critical Care Clinics. 2009;25:373–382.

44. Chang TM S. Blood replacement with nanobiotechnologically engineered hemoglobin and hemoglobin nanocapsules. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2010;2:418–430.

45. Chang TM S, Malave N. The development and first clinical use of semipermeable microcapsules (artificial cells) as a compact artificial kidney. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1970;16:141–148.

46. Chang TM S, Poznansky MJ. Semipermeable microcapsules containing catalase for enzyme replacement in acatalsaemic mice. Nature. 1968;218:242–245.

47. Chang TM S, Prakash S. Microencapsulated genetically engineered cells: Comparison with other strategies and recent progress. Mol Med Today. 1998b;4:221–227.

48. Chang TMS, Yu WP. Biodegradable polymer membrane containing hemoglobin as potential blood substitutes. 1992; British Provisional Patent No. 9219426.5 (issued Sept. 14, 1992).

49. Chang TM S, Macintosh FC, Mason SG. Semipermeable aqueous microcapsules: I Preparation and properties. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1966;44:115–128.

50. Chang TM S, Coffey JF, Barre P, Gonda A, Dirks JH, et al. Microcapsule artificial kidney: Treatment of patients with acute drug intoxication. Can Med Assoc J. 1973;108:429–433.

51. Chang TMS, Langer R, Sparks RE, Reach G. Drug delivery systems in biotechnology. J Artif Organs. 1988;12:248–251.

52. Chang TM S, Bourget L, Lister C. A new theory of enterorecirculation of amino acids and its use for depleting unwanted amino acids using oral enzyme artificial cells, as in removing phenylalanine in phenylketonuria. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1995;25:1–23.

53. Chang TMS, D’Agnillo F, Razack S. Cross-linked hemoglobin superoxide dismutase-catalase: A second generation hemoglobin based blood substitute with antioxidant activities. In: Chang TMS, ed. Blood Substitutes: Principles, Methods, Products and Clinical Trials (Vol 2. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 1998;178–196.

54. Chang TMS, D’Agnillo F, Yu WP, Razack S. New generations of blood subsitutes based on polyhemoglobin-SOD-CAT and nanoencapsulation. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2000;40:213–218.

55. Chang TM S, Powanda D, Yu WP. Analysis of polyethyleneglycolpolylactide nano-dimension artificial red blood cells in maintaining systemic hemoglobin levels and prevention of methemoglobin formation. Artif Cells Blood Substit Biotechnol. 2003;31:231–248.

56. Chow KM, Liu ZC, Prakash S, Chang TM S. Free and microencapsulated Lactobacillus and effects of metabolic induction on Urea Removal Artificial Cells. Blood Substit and Biotechnol. 2003;4:425–434.

57. Cirone P, Bourgeois M, Austin RC, Chang PL. A novel approach to tumor suppression with microencapsulated recombinant cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:1157–1166.

58. Cousineau J, Chang TM S. Formation of amino acid from urea and ammonia by sequential enzyme reaction using a microencapsulated multienzyme system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977;79:24–31.

59. D’Agnillo F, Chang TM S. Polyhemoglobin-superoxide dismutasecatalase as a blood substitute with antioxidant properties. Nature Biotechnol. 1998;16:667–671.

60. Dalle B, Payen E, Regulier E, Deglon N, Rouyer-Fessard P, et al. Improvement of the mouse ß-thalassemia upon erythropoietin delivery by encapsulated myoblasts. Gene Ther. 1999;6:157–161.

61. De Vos P, Hamel AF, Tatarkiewicz K. Considerations for successful transplantation of encapsulated pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2002;45:159–173.

62. Deamer DW, Bangham AD. Large-volume liposomes by an ether vaporization method. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;443:629–634.

63. Discher BM, Won Y, David SE. Polymersomes: Tough vesicles made from diblock copolymers. Science. 1999;284:1143–1144.

64. Djordjevich L, Miller IF. Synthetic erythrocytes from lipid encapsulated hemoglobin. Exp Hematol. 1980;8:584.

65. Garofalo FA, Chang TM. Effects of mass transfer and reaction kinetics on serum cholesterol depletion rates of free and immobilized. Pseudomonas pictorum Appl Biochem.Biotech. 1991;27:75–91.

66. Gould SA, et al. The clinical development of human polymerized hemoglobin. In: Chang TM S, ed. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 1998;12–28. Blood Substitutes: Principles, Methods, Products and Clinical Trials. Vol. 2.

67. Gould SA, Moore EE, Hoyt DB, Ness PM, Norris EJ, et al. The life-sustaining capacity of human polymerized hemoglobin when red cells might be unavailable. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:445–452.

68. Greenburg AG, Kim HW. Evaluating new red cell substitutes: A critical analysis of toxicity models. Biomater Artif Cells Immobil Biotechnol. 1992;20:575–581.

69. Gregoriadis G. Drug Carriers in Biology and Medicine. New York, NY: Academic Press, Inc; 1976.

70. Gu G, Chang TM S. Extraction of erythrocyte enzymes for the preparation of Polyhemoglobin-catalase-superoxide dismutase. Artif Cells, Blood Substit and Biotechnol. 2009;37:69–77.

71. Gu KF, Chang TM S. Conversion of alpha-ketoglutarate into L-glutamic acid with urea as ammonium source using multienzyme system and dextran-NAD+ immobilised by microencapsulation with artificial cells in a bioreactor. J Bioeng Biotechnol. 1988;32:363–368.

72. Gu KF, Chang TM S. Production of essential L-branched-chained amino acids, in bioreactors containing artificial cells immobilized multienzyme systems and dextran-NAD+. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1990;26:263–269.

73. Hagihara Y, Saitoh Y, Iwata H, Taki T, Hirano S, et al. Transplantation of xenogeneic cells secreting beta-endorphin for pain treatment: Analysis of the ability of components of complement to penetrate through polymer capsules. Cell Transplan. 1997;6:527–530.

74. Hakim RM, Milford E, Himmelfarb J, Wingard R, Lazarus JM, et al. Extracorporeal removal of antiHLA antibodies in transplant candidates. Am J Kidney Dis. 1990;16:423.

75. Hunkeler DL. Bioartificial organ grafts: A view at the beginning of the third millennium. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 2003;31:365–382.

76. Ilan E, Chang TM S. Modification of lipid–polyamide microcapsules for immobilization of free cofactors and multienzyme system for the conversion of ammonia to glutamate. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1986;13:221–230.

77. Ito Y, Chang TM S. In vitro study of multicellular hepatocytes spheroid formed in microcapsules. J Artif Organs. 1992;16:422–426.

78. Jahr JS, Mackenzie C, Pearce LB, Pitman A, Greenburg AG. HBOC-201 as an alternative to blood transfusion: Efficacy and safety evaluation in a multicenter phase III trial in elective orthopaedic surgery. J Trauma. 2008;64:1484–1497.

79. Kashani SA, Chang TM S. Release of hepatic stimulatory substance from cultures of free and microencapsulated hepatocytes: Preliminary report. J Biomater Artif Cells Artif Organs. 1988;16:741–746.

80. Kashani S, Chang TM S. Effects of hepatic stimulatory factor released from free or microencapsulated hepatocytes on galactosamine induced fulminant hepatic failure animal model. Biomater Artif Cells Immobil Biotechnol. 1991;19:579–598.

81. Kawasaki C, Nishi R, Uekihara S, Hayano S, Otagiri M. Charcoal hemoperfusion in the treatment of phenytoin overdose. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:323–326.

82. Keipert PE, Chang TM S. Pyridoxylated polyhemoglobin as a blood substitute for resuscitation of lethal hemorrhagic shock in conscious rats. Biomater Med Dev Artif Organs. 1985;13:1–15.

83. Keipert PE, Chang TM S. In vivo effects of total and partial isovolemic exchange transfusion in fully conscious rats using pyridoxylated polyhemoglobin solution as a colloidal oxygen-delivery blood substitute. Vox Sang. 1987;53:7–14.

84. Kobayashi K, Izumi Y, Yoshizu A, Horinuchi H, Park SI, et al. The oxygen carrying capability of hemoglobin vesicles evaluated in rat exchange transfusion models. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1997;25:357–366.

85. LaVan DA, Lynn DM, Langer R. Moving smaller in drug discovery and delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:77–84.

86. Lim F, Sun AM. Microencapsulated islets as bioartificial endocrine pancreas. Science. 1980;210:908–909.

87. Lin CC, Chou HL, Lin JL. Acute aconitine poisoned patients with ventricular arrhythmias successfully reversed by charcoal hemoperfusion. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:66–67.

88. Lin CC, Chan TY, Deng JF. Clinical features and management of herb induced aconitine poisoning. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:574–579.

89. Liu J, Jia X, Zhang J, Hu W, Zhou Y. Study on a novel strategy to treatment of phenylketonuria. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 2002;30:243–258.

90. Liu ZC, Chang TM S. Effects of bone marrow cells on hepatocytes: When cocultured or co-encapsulated together. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 2000;28:365–374.

91. Liu ZC, Chang TM S. Increased viability of transplantation hepatocytes when coencapsulated with bone marrow stem cells using a novel method. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 2002;30 99–11.

92. Liu ZC, Chang TM S. Coencapsulation of stem sells and hepatocytes: In vitro conversion of ammonia and in vivo studies on the lowering of bilirubin in Gunn rats after transplantation. Int J Artif Organs. 2003;26:491–497.

93. Liu ZC, Chang TM S. Transplantation of bioencapsulated bone marrow stem cells improves hepatic regeneration and survival of 90% hepatectomized rats: A preliminary report. Artif Cells Blood Substit Biotechnol. 2005;33:405–410.

94. Liu ZC, Chang TM S. Transdifferentiation of bioencapsulated bone marrow cells into hepatocyte-like cells in the 90% hepatectomized rat model. J Liver Transplant. 2006;12:566–572.

95. Liu ZC, Chang TM S. Long term effects on the histology and function of livers and spleens in rats after 33% toploading of PEG-PLA-nano-artificial red blood cells. Artif.Cells, Blood Substit and Biotechnol. 2008;36:513–524.

96. Liu ZC, Chang TM S. Preliminary study on intrasplenic implantation of artificial cell bioencapsulated stem cells to increase the survival of 90% hepatectomized rats. Artif Cells, Blood Substit and Biotechnol. 2009;37(1):53–55.

97. Liu ZC, Chang TM S. Artificial cell microencapsulated stem cells in regenerative medicine, tissue engineering and cell therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;670:68–79.

98. Lloyd-George I, Chang TM S. Characterization of free and alginate polylysine-alginate microencapsulated Erwinia herbicola for the conversion of ammonia, pyruvate and phenol into L-tyrosine and L-DOPA. J Bioeng Biotechnol. 1995;48:706–714.

99. Lopez Lago AM, Rivero Velasco C, Galban Rodríguez C, Mariño Rozados A, Piñero Sande N, et al. Paraquat poisoning and hemoperfusion with activated charcoal. Ann Intern Med. 2002;19:310–312.

100. Lorh M, Hoffmeyer A, Kroger JC. Microencapsulated cell-mediated treatment of inoperable pancreatic carcinoma. Lancet. 2001;357:1591–1592.

101. Luzzi LA. Preparation and evaluation of the prolonged release properties of nylon microcapsules. J Pharm Sci. 1970;59:338.

102. Michalopoulos G, Houck KD, Dolan ML, Luetteke NC. Control of hepatocyte replication by two serum factors. Cancer Res. 1984;44:4414–4419.

103. Moore EE, Moore FA, Fabian TC, Bernard AC, Fulda GJ, et al. Human polymerized hemoglobin for the treatment of hemorrhagic shock when blood is unavailable: The USA Multicenter Trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:1–13.

104. Orive G, Hernández RM, Gascón AR, Calafiore R, Chang TM, et al. Cell encapsulation: Promise and progress. Nat Med. 2003;9:104–107.

105. Orive G, Hernández RM, Gascón AR, Calafiore R, Chang TM, et al. History, challenge and perspectives of cell microencapsulation. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:87–92.

106. Palmour RM, Goodyer P, Reade T, Chang TM S. Microencapsulated xanthine oxidase as experimental therapy in Lesch-Nyhan disease. Lancet. 1989;2:687–688.

107. Pearce LB, Gawryl MS. Overview of preclinical and clinical efficacy of Biopure’s HBOCs. In: Chang TM S, ed. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 1998;82–98. Blood Substitutes: Principles, Methods, Products and Clinical Trials. Vol. 2.

108. Pearce LB, Gawryl MS, Rentko VT, et al. HBOC-201 (Hb Glutamer-250 (Bovine), Hemopure): Clinical studies. In: Winslow R, ed. Blood Substitutes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2006;437–450.

109. Peng A, Meng FQ, Sun LF, Ji ZS, Li YH. Therapeutic efficacy of charcoal hemoperfusion in patients with acute severe dichlorvos poisoning. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2004;25:15–21.

110. Philips WT, Klipper RW, Awasthi VD, Rudolph AS, Cliff R, et al. Polyethylene glyco-modified liposome-encapsulated hemoglobin: A long circulating red cell substitute. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1999;288:665–670.

111. Photos PJ, Bacakova L, Discher B, Bates FS. Polymer vesicles in vivo: Correlations with PEG molecular weight. J Control Release. 2003;90:323–334.

112. Powanda D, Chang TM S. Cross-linked polyhemoglobin-superoxide dismutase-catalase supplies oxygen without causing blood brain barrier disruption or brain edema in a rat model of transient global brain ischemia-reperfusion. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 2002;30:25–42.

113. Poznansky MJ, Chang TM S. Comparison of the enzyme kinetics and immunological properties of catalase immobilized by microencapsulation and catalase in free solution for enzyme replacement. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;334:103–115.

114. Prakash S, Chang TM S. Genetically engineered E. coli cells containing K. aerogenes gene, microencapsulated in artificial cells for urea and ammonia removal. Biomater Artif Cells Immobil Biotechnol. 1993;21:629–636.

115. Prakash S, Chang TM S. Microencapsulated genetically engineered live E. coli DH5 cells administered orally to maintain normal plasma urea level in uremic rats. Nature Med. 1996;2:883–887.

116. Razack S, D’Agnillo F, Chang TM S. Cross-linked hemoglobin superoxide dismutase-catalase scavenges free radicals in a rat model of intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1997;25:181–192.

117. Rokstad AM, Holtan S, Strand B, Steinkjer B, Ryan L, et al. Microencapsulation of cells producing therapeutic proteins: Optimizing cell growth and secretion. Cell Transplant. 2002;11:313–324.

118. Rosenthal AM, Chang TMS. The effect of valinomycin on the movement of rubidium across lipid coated semipermeble microcapsules. Proc Canad Fed Biol Soc. 1971;14:44.

119. Rosenthal AM, Chang TMS. The incorporation of lipid and Na+-K+-ATPase into the membranes of semipermeable microcapsules. J Membrane Sciences. 1980;6(3):329–338.

120. Safos S, Chang TM S. Enzyme replacement therapy in ENU2 phenylketonuric mice using oral microencapsulated phenylalanine ammonialyase: A preliminary report. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1995;23:681–692.

121. Saitoh Y, Taki T, Arita N, Ohnishi T, Hayakawa T. Cell therapy with encapsulated xenogeneic tumor cells secreting beta-endorphin for treatment of peripheral pain. Cell Transplant. 1995;S1:S13–S17.

122. Sakai H, Masada Y, Horinouchi H, Yamamoto M, Ikeda E, et al. Hemoglobin-vesicles suspended in recombinant human serum albumin for resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock in anesthetized rats. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:539–545.

123. Sarkissian CN, Shao Z, Blain F, Peevers R, Su H, et al. A different approach to treatment of phenylketonuria: Phenylalanine degradation with recombinant phenylalanine ammonia lyase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:2339–2344.

124. Singh SM, McCormick BB, Mustata S, Thompson M, Prasad GV. Extracorporeal management of valproic acid overdose: A large regional experience. J Nephrol. 2004;17:43–49.

125. Spangrude GJ, Heimfeld S, Weissman IL. Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1988;241:58–62.

126. Sprung J, Kindscher JD, Wahr JA, Levy JH, Monk TG, et al. The use of bovine Hb glutamer-250 (Hemopure) in surgical patients: Results of a multicenter, randomized, singleblinded trial. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:799–808.

127. Sun YL, Ma XJ, Zhou DB. Normalization of diabetes in spontaneously diabetic cynomologus monkeys by xenografts of microencapsulated porcine islets without immunosuppression. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1417–1422.

128. Tan SA, Déglon N, Zurn AD, Baetge EE, Bamber B, et al. Rescue of motoneurons from axotomy-induced cell death by polymer encapsulated cells genetically engineered to release CNTF. Cell Transplant. 1996;5:577–587.

129. Terman DS, Tavel T, Petty D, Racic MR, Buffaloe G. Specific removal of antibody by extracorporeal circulation over antigen immobilized in colodion charcoal. Clin Exp Immunol. 1977;28:180–188.

130. Terman DS, Buffaloe G, Mattioli C, Cook G, Tiilquist R, et al. Extracorporeal immunoabsorption: Initial experience in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 1979;2:824.

131. Torchilin VP. Recent advances with liposomes as pharmaceutical carriers. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:145–160.

132. Present and Future Perspectives Blood Substitutes. Vol. 1. Tsuchida E, ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1998.

133. Winchester JF, ed. Replacement of Renal Function by Dialysis. Boston, MD: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996.

134. Wingard RL, Lee WO, Hakim RO. Extracorporeal treatment of familial hypercholesterolemia with monoclonal antibodies to low-density lipoproteins. Am J Kidney Dis. 1991;18:559.

135. Winn SR, Hammang JP, Emerich DF, Lee A, Palmiter RD, et al. Polymer-encapsulated cells genetically modified to secrete human nerve growth factor promote the survival of axotomized septal cholinergic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2324–2328.

136. Wong H, Chang TM S. Bioartificial liver: Implanted artificial cells microencapsulated living hepatocytes increases survival of liver failure rats. Int J Artif Organs. 1986;9:335–336.

137. Wong H, Chang TM S. The viability and regeneration of artificial cell microencapsulated rat hepatocyte xenograft transplants in mice. J Biomater Artif Cells Artif Organs. 1988;16:731–740.

138. Wong H, Chang TM S. A novel two-step procedure for immobilizing living cells in microcapsule for improving xenograft survival. Biomater Artif Cells Immobil Biotechnol. 1991;19:687–698.

139. Wong N, Chang TM S. Polyhemoglobin-fibrinogen: A novel blood substitute with platelet-like activity for extreme hemodilution. Artif Cells, Blood Substit and Biotechnol. 2007;35:481–489.

140. Xu W, Liu L, Charles IG. Microencapsulated iNOS-expressing cells cause tumor suppression in mice. FASEB J. 2002;16:213–215.

141. Yang L, Cheng Y, Yan WR, Yu YY. Extracorporeal whole blood immunoadsorption of autoimmune myasthenia gravis by cellulose tryptophan adsorbent. Artif Cells, Blood Substit Biotechnol. 2004;32 519–518.

142. Yu BL, Chang TM S. In vitro and in vivo effects of poly hemoglobintyrosinase on murine B16F10 melanoma. Melanoma Res J. 2004;14:197–202.

143. Yu WP, Chang TM S. Submicron biodegradable polymer membrane hemoglobin nanocapsules as potential blood substitutes: A preliminary report. J Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1994;22:889–894.

144. Yu WP, Chang TM S. Submicron polymer membrane hemoglobin nanocapsules as potential blood substitutes: Preparation and characterization. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1996;24:169–184.

145. Yu WP, Wong J, Chang TM S. Preparation and characterization of polylactic acid microcapsules containing ciprofloxacin for controlled release. J Microencapsul. 1998;15:515–523.

146. Yu WP, Wong JP, Chang TM S. Sustained drug release characteristics of biodegradable composite poly(d, l)lactic acid poly(l)lactic acid microcapsules containing ciprofloxacin. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 2000;28:39–56.

147. Yu YT, Chang TM S. Immobilization of multienzymes and cofactors within lipid-polyamide membrane microcapsules for the multistep conversion of lipophilic and lipophobic substrates. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1982;4:327–331.

148. Zhou MX, Chang TM S. Control release of prostaglandin E2 from polylactic acid microcapsules, microparticles and modified microparticles. J Microencapsul. 1988;5:27–36.