Chapter II.6.8

Cartilage and Ligament Tissue Engineering

Biomaterials, Cellular Interactions, and Regenerative Strategies

Introduction to Cartilage and Ligament Tissue Engineering

The musculoskeletal system is responsible for complex movements that are performed many thousands of times over a lifetime. Two connective tissues of the musculoskeletal system, cartilage and ligament, protect the body from injuries during these movements, primarily by absorbing loads and maintaining joint stability, respectively. Relative to other musculoskeletal tissues, cartilage and ligament have low oxygen and nutrient requirements, low cell density, and poor regenerative capacity, yet they experience some of the highest mechanical loads in the body. When these loads exceed a critical threshold that causes permanent tissue damage, or if diseases cause severe tissue degeneration, these problems often result in a significant locomotive impairment. For the repair of both tissues, given their very low self-regenerative capacity, typically the only recourse is surgical intervention. Current surgical reparative techniques rely upon total joint replacement or grafting, and are often accompanied with further musculoskeletal problems; a more ideal solution would be to use a biological approach to repair the defects and fully restore the cartilage or ligament tissue to its pre-injured state. This is the promise of tissue engineering, a new field which generally aims to incorporate specific cell types into a biodegradable scaffold which, when implanted, will gradually regenerate into a tissue that closely resembles the original tissue and restores functionality. In this chapter, we outline the state of the art of cartilage and ligament tissue engineering, divided into two sections, with emphasis ranging from biomaterial selection and functionalization, cellular activities critical for tissue function, scaffold design to mimic native tissue composition, to recent outcomes of long-term implantation studies in animal models.

Cartilage Tissue Engineering

Introduction to Cartilage Tissue Engineering

Cartilage is a connective tissue that functions to absorb mechanical impact, assist joint motion, provide structural support, and connect soft and hard tissues. There are three types of human cartilage: hyaline, elastic, and fibrocartilage, located at different parts of the body, and each type of cartilage features a unique composition and structure specifically suitable for carrying out the aforementioned tissue functions. Like other musculoskeletal tissues primarily responsible for mechanical and structural functions, cartilage plays an important role in protecting the body from mechanical impacts during physical activities. Therefore, any damage significantly impeding cartilage function may also affect functional capabilities of the musculoskeletal system.

Clinical Relevance and Limitations of Current Repair Strategies

Cartilage damage is a common problem often seen in clinical orthopedics. The causes and mechanisms leading to cartilage damage can be physical, biological or both. Physical causes, such as trauma, often damage the tissue structure and injure cells, creating permanent lesions in cartilage. On the other hand, biological causes, such as those related to autoimmunity and inflammation, trigger catabolic cellular and biochemical activities that degrade cartilage. Among these, osteoarthritis (OA), an aging-related disease, is the leading cause of cartilage degeneration. While OA is a joint problem commonly found in the aged population, the current trend has shown a decrease in the average age of the OA population. Obesity is one of the major factors triggering the early development of OA, and is likely to involve biological and physical mechanisms. As one of the leading causes of disability among the US adult population, OA significantly not only affects the quality of an individual’s life, but also brings enormous societal and financial burdens to the healthcare system. Annually, OA treatment incurs more than 185.5 billion US dollars of healthcare cost, and this number is expected to increase rapidly in the next few decades when the baby boomer generation ages (Kotlarz et al., 2009). By the year 2030, it is estimated that 25% or more of the population in the US would likely suffer from arthritis. These demographic and health-cost estimates clearly illustrate the disease burden of OA, and indicate the urgent need to develop an effective therapy to treat OA, as well as other cartilage-related health problems.

Cartilage is a hypo-cellular tissue that does not contain blood and lymphatic vessels to support circulation of repair cells and molecules, such as growth factors and cytokines, to initiate wound healing of lesions once injured. Therefore, cartilage lesions often progress with time in an almost irreversible manner. Current treatments to cartilage lesions include non-surgical therapies and surgical interventions (Hunziker, 2002). Non-surgical treatments, such as drug or physical therapy, are generally used for the early stage of OA or cartilage with a minor lesion, whereas surgical interventions are necessary for mid- and late-stage OA or cartilage with a severe lesion. The clinical gold standard to treat severe cartilage lesions is total joint replacement, an effective but final resort surgical procedure to restore joint functions. For patients with less severe cartilage lesions, other surgical procedures, such as arthroscopic abrasion and debridement, microfracture, osteochondral plug transplantation or mosaicplasty, and autologous chondrocyte implantation, are used to repair lesions. Clinical results have shown that although these surgical procedures are able to provide some improvements to the disease state, there are inherent complications, such as fibrocartilage formation and donor site tissue morbidity.

The Modern Cartilage Engineering Strategy

Cartilage tissue engineering is an emerging method for therapeutic repair and regeneration of cartilage. The first cartilage tissue engineering attempt may be traced back to the 1970s, when a pediatric surgeon, Dr. W. T. Green, cultured rabbit chondrocytes on decalcified bone and transplanted the cellular structure into cartilage defects (Green, 1977). Although the outcome of the study was not satisfactory, this pioneer study introduced the innovative concept of cartilage tissue engineering. In 1991, Vacanti et al. implanted chondrocyte-laden poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) scaffolds subcutaneously in nude mice to regenerate cartilage (Vacanti et al., 1991). The research team successfully demonstrated the feasibility of using a tissue engineering approach to regenerate new cartilage. Two years later, Freed and co-workers used a bioreactor system to grow chondrocyte-laden biodegradable scaffolds ex vivo, and showed significantly enhanced production of cartilage matrix in the bioreactor-grown cartilage, compared to static culture-grown cartilage (Freed et al., 1993). In the past two decades, the introduction of stem cells, smart biomaterials, and bioreactors have continued to enhance cartilage tissue engineering.

The principal concept of cartilage tissue engineering is to seed chondrocytes or chondroprogenitor cells within a three-dimensional biomaterial scaffold which is then cultured in a bioreactor to produce functional cartilage in vitro, which is then implanted in vivo. Alternatively, a three-dimensional biomaterial scaffold is used as a carrier to deliver therapeutic cells to facilitate cartilage regeneration at a defect site, without being pre-cultured in vitro. Critical to the success of these cartilage tissue engineering strategies are the physical and chemical properties of biomaterial scaffolds, which must be able to provide mechanical strength, as well as to regulate biological activities of the seeded cells and their chondrocytic phenotype. In the past two decades, a great number of biomaterials and three-dimensional structures, including many novel materials and scaffolds, have been introduced into cartilage tissue engineering. By including cutting-edge nanotechnologies, peptide synthesis and controlled release, novel scaffolds with intelligent materials and structures are capable of changing their physical or chemical properties in response to physiological needs to enhance cell growth and tissue regeneration.

Macromolecular Composition and Structure of Native Cartilage

Cartilage Composition

Chondrocytes are the sole cell type in cartilage, and make up 5–10% of total tissue volume. Besides chondrocytes, other major components of cartilage are specific extracellular matrix (ECM) macromolecules, and water (Buckwalter and Mankin, 1998). The ECM constitutes 20–40% of the tissue volume, and the water content amounts to 70% of the total tissue weight. Despite a minor fraction of the total tissue volume occupied by chondrocytes, activities of chondrocytes are critical to the anabolism and catabolism of cartilage, i.e., chondrocytes continue to synthesize and break down ECM components to maintain healthy matrix turnover under the influence of autocrine or paracrine signals (Stockwell, 1979).

The ECM of cartilage consists of collagens, non-collagenous proteins, and proteoglycans (Buckwalter and Mankin, 1998). Collagenous ECM components include collagen types I, II, VI, IX, X, and XI (Eyre et al., 1992). In hyaline cartilage, a small quantity of collagen type I accumulates in the superficial zone, while collagen type II is ubiquitously present in cartilage and accounts for 90–95% of total collagen (Kuettner, 1992). Both collagen types I and II play a mechanical role in maintaining tissue structure integrity by providing strength to resist tensile loading. Collagen type VI is localized around chondrocytes, and has been postulated to play a role in mechano-biological regulation. Collagen type IX functions as a linker molecule that binds to collagen type II to stabilize collagen type II fibril assembly (Mendler et al., 1989). Collagen type X is produced by hypertrophic chondrocytes, and is mostly found in the calcified zone of the cartilage growth plate. Collagen type XI constitutes 5–10% of the total collagen content. Its function is not clear but likely associated with stabilization of the collagen network (Swoboda et al. 1989).

Non-collagenous proteins of the cartilage ECM are also involved in structuring the ECM and regulating chondrocyte activities (Heinegard and Pimentel, 1992). For example, the proteoglycan link protein serves to link aggrecan with hyaluronic acid (Ruoslahti, 1988), and fibronectin regulates chondrocyte adhesion to the ECM (Hayashi et al., 1996). Proteoglycans make up the bulk of the non-collagenous ECM components of cartilage, including large aggregating proteoglycans, such as aggrecan and versican, and small leucine-rich proteoglycans, such as decorin and biglycan (Prydz and Dalen, 2000). In hyaline articular cartilage, aggrecan is composed of a core protein, covalently modified with sulfated glycosaminoglycan (sGAG) molecules that make up about 90% of the total proteoglycan mass (Roughley and Lee, 1994). Sulfated GAGs, such as chondroitin sulfate, dermatan sulfate, heparan sulfate, and keratan sulfate, have a long polysaccharide chain that consists of repeating disaccharide units with sulfate groups. These sulfated polysaccharides carry a large amount of negative charge to attract and retain water between the matrix molecules, thus creating hydrostatic resistance to compressive loading (Mow and Wang, 1999).

Cartilage Structure

Although the articular cartilage of a human joint is only a few millimeters in thickness, it is capable of mediating smooth joint motion, and protecting subchondral bone from mechanical damage. This property of the articular cartilage is attributed to the existence of four regional zones in the tissue, with specific cell activities, and ECM structure and composition associated with each zone (Buckwalter and Mankin, 1998). The four zones from the top down are the superficial, middle, deep, and calcified zones (Farnworth, 2000). The superficial zone consists of a large amount of fibrillar collagen and water, but a small amount of proteoglycans (Venn, 1978). Collagen fibrils run parallel to each other and the joint surface, conferring high tensile and shear strength (Kempson et al., 1973). Chondrocytes in this zone are flattened, ellipsoid-shaped, and synthesize low molecular weight proteoglycans (Hasler et al., 1999). The middle zone lies beneath the superficial zone, and has several times the volume of the superficial zone. This zone features a lower cell number, the presence of spherical chondrocytes, and a large amount of proteoglycans (Venn, 1978). Chondrocytes produce fewer but larger randomly-oriented collagen fibrils in the middle zone, compared to those fibrils in the superficial zone. Located beneath the middle zone is the deep zone; this zone contains the largest collagen fibrils, the greatest amount of proteoglycans, and the lowest cell number, compared to the other three zones. Chondrocytes in this zone maintain a spherical shape, and the collagen fibrils are perpendicular to the joint surface (Hunziker et al., 1997). The deep zone is capable of providing substantial resistance to compressive loading because of the large amount of proteoglycans and the perpendicular collagen fibrils. The calcified cartilage zone is a transition zone located between the deep zone and subchondral bone. Chondrocytes in this zone are hypertrophic and exhibit low metabolic activities (Bullough and Jagannath, 1983).

Important Considerations in Designing and Fabricating a Cartilage Tissue Engineered Scaffold

Functionally, a tissue engineered scaffold represents an artificial ECM to accommodate, protect, and interact with cells residing in the structure during tissue regeneration. An ideal tissue engineered scaffold should be able to substitute for native ECM, and faithfully carry out ECM functions. In order to design an ideal scaffold for cartilage tissue engineering, it is essential to identify the critical cellular activities and material properties required for robust cartilage regeneration, and to select the biomaterial(s) that is best able to represent these characteristics.

Cellular Activity Requirements

Maintenance of the Phenotypic Spherical Shape of Chondrocytes

Cell morphology is an important aspect of the phenotype of a cell, and is critical in the regulation of cell activities. In native cartilage, chondrocytes are embedded in dense ECM, and exhibit a characteristic spherical morphology which is critical for maintaining the chondrocytic phenotype. Numerous in vitro studies have shown that after chondrocytes are isolated from cartilage and cultured as a monolayer surface, the cells change from a spherical to a spindle, elongated shape, and dedifferentiate into fibroblast-like cells. Unlike phenotypic chondrocytes that produce collagen type II and aggrecan, dedifferentiated cells produce collagen type I, decorin, and biglycan. Indeed, spindle shaped dedifferentiated chondrocytes show distinct cell activities, compared to spherical chondrocytes. However, the dedifferentiated cells can be redifferentiated back to phenotypic chondrocytes if they are encapsulated in a hydrogel or cultured on a low-adhesivity surface to re-establish a spherical morphology. Assumption and maintenance of a spherical cell shape is also a requirement for effective chondrogenesis of embryonic limb mesenchymal cells and adult mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), as exemplified by a high cell-seeding density of these cells used in three-dimensional micromass or pellet culture for chondrogenic differentiation (see below).

Establishment of Biologically Favorable Three-dimensional Cell–Cell and Cell–Matrix Interactions

During embryonic chondrogenesis, mesenchymal cells undergo cell condensation, which is a critical and necessary step for chondrogenic differentiation (Fell, 1925). The cell condensation process is responsible for the initiation of specific, three-dimensional cell–cell interactions, such as N-cadherin mediated cell adhesion and gap junctional communication (Oberlender and Tuan, 1994), to activate chondrogenic signaling events for cartilage formation. For ex vivo chondrogenesis, the commonly used high-density cell pellet culture imitates the cell condensation process by densely packing cells via centrifugation to enhance three-dimensional cell–cell interactions. In addition to cell–cell interactions, cell–matrix interactions represent another critical mechanism that is involved in the regulation of chondrocyte activities in mature cartilage. After initial chondrogenesis, the resultant chondrocytes synthesize abundant ECM which is deposited around the cells, thus gradually separating cells from each other. In this manner, in mature cartilage, chondrocytes interact intimately with the pericellular ECM to maintain cartilage functions.

Material Property Requirements

Presentation of Biocompatible Surface Chemistry and Topography on Scaffolds

Surface chemical and physical properties of scaffolding materials must be biocompatible, and not elicit immunogenic or inflammatory responses from seeded cells or adjacent host tissues surrounding the scaffold. In addition, byproducts released from the scaffold as a result of biodegradation or bioresorption must be non-toxic, and not cause undesirable host reactions. Alternatively, any unwanted byproducts must be effectively removed from the local microenvironment. This characteristic is particularly important for cartilage tissue engineering because of the non-vascular nature of cartilage, which precludes vasculature as an efficient means of byproduct removal, with diffusion as the only mechanism available.

Construction of Scaffolding Structures with ECM-Mimetic Geometry

There is mounting evidence that physical properties of a biomaterial scaffold can instruct cell behavior, thus ultimately determining the fate of an engineered tissue. For example, scaffolds with nanosized or microsized structure create different patterns of cell–matrix interaction with seeded chondrocytes to modulate cell morphology and cytoskeletal organization, in turn resulting in different gene and protein expressions (Li et al., 2006a).

Mechanical Properties

In addition to functioning as structural templates to direct tissue growth and to determining the size and shape of regenerated cartilage, scaffolds must also provide protection for the neocartilage from mechanical damage. In the process of cartilage tissue engineering, mechanical challenges could occur during in vitro regeneration with mechanical loading stimulating tissue growth or post-implantation when the joints are subjected to natural weightbearing functions. Ideal scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering must be able to protect cells from damage, and maintain structural integrity of tissue-engineered constructs to provide a mechanically stable environment to seeded cells during the tissue regeneration process.

Biomaterials in Cartilage Tissue Engineering

Synthetic Biomaterials for Cartilage Tissue Engineering

Poly(α-hydroxy esters) – Members of poly(α-hydroxy esters) are the most commonly used synthetic biodegradable polymer for cartilage tissue engineering. An advantage of using poly(α-hydroxy esters) as cartilage tissue engineering scaffolds is their prior approval by the US Food and Drug Agency for clinical use as bioresorbable biomaterials. Among the poly(α-hydroxy ester) members, poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), poly(lactic acid) (PLA), PLGA, and poly (ε-caprolactone) (PCL) have been extensively investigated for the use in fabrication of cartilage tissue-engineered scaffolds. PGA is a semi-crystalline, hydrophilic polymer, and may rapidly degrade in an aqueous solution. PLA, with the addition of a methyl group, is a more hydrophobic, semi-crystalline polymer, and degrades more slowly than PGA (Middleton and Tipton, 2000). The three stereoisomers, D, L, and D and L mixture, referring to the different conformation of the methyl group, exhibit distinct properties. For example, poly(l-lactic acid) (PLLA) has a higher melting temperature and degrades more slowly than poly(d, l-lactic acid) (PDLLA). Furthermore, PGA and PLA can be copolymerized in different ratios to form a new polymer, PLGA, with properties different from either of the two constituent polymers. Poly (ε-caprolactone) (PCL) is another semi-crystalline biodegradable polymer. Compared to other poly(α-hydroxy ester) members, PCL is less commonly used in the fabrication of scaffolds, mainly because its slow degradation may interfere with deposition of newly synthesized ECM. Recently, PCL has been blended or copolymerized with other poly(α-hydroxy esters) to fabricate new polymers with controlled properties for meeting the needs of fabricating working scaffolds (Middleton and Tipton, 2000).

The use of PLA scaffolds to culture chondrocytes, followed by implantation of the cell-seeded scaffold in an animal model to regenerate cartilage was first reported in the early 1990s (Vacanti et al., 1991). After this pioneer study, PLA, PGA, and PLGA have been fabricated into various structured scaffolds to culture chondrocytes or MSCs to regenerate cartilage in vitro or in vivo. Studies have shown that effective in vivo cartilage regeneration can be achieved by seeding and culturing chondrocytes on PGA scaffolds in vitro, followed by in vivo implantation (Chu et al., 1995; Liu et al., 2002), suggesting that the process of in vitro cartilage tissue engineering might allow chondrocytes to produce sufficient ECM to stabilize the newly synthesized tissue structure while PGA undergoes degradation. Unlike natural biopolymers that are often prepared in a hydrogel form, the poly(α-hydroxy esters) are commonly fabricated into various pre-formed structures, such as fiber, foam, and sponge.

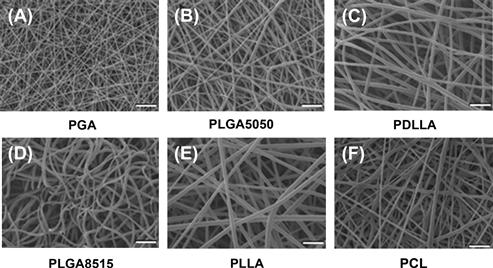

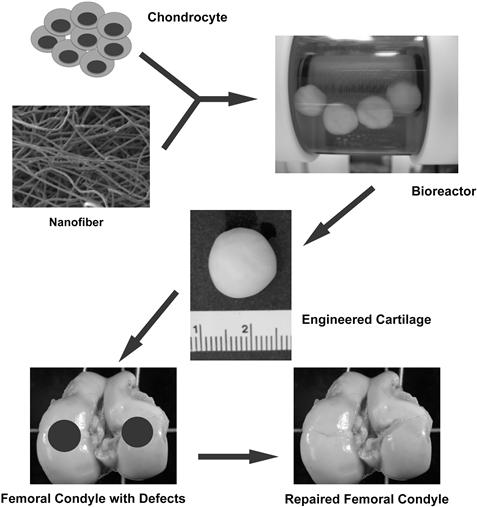

Developing nanostructural materials as scaffolds is an emerging trend in tissue engineering. Nanostructured scaffolds, such as nanofibrous scaffolds, can be fabricated using the electrospinning technique. Several poly(α-hydroxy esters) have been successfully fabricated into nanofibrous scaffolds (Figure II.6.8.1) (Li et al., 2006b). These different poly(α-hydroxy ester)-based nanofibrous scaffolds possess a range of mechanical properties and degradation profiles that render them as suitable scaffolds for different engineered tissues. For example, chondrocytes cultured in PLLA or PCL nanofibrous scaffolds maintained their chondrocytic phenotype (Li et al., 2003), and MSCs in the same structure were successfully induced into chondrocytes (Li et al., 2005). Furthermore, an in vivo study showed that the chondrocyte- or MSC-laden nanofibrous scaffold was able to repair full-thickness cartilage defects created in pig femoral condyles (Figure II.6.8.2) (Li et al., 2009).

FIGURE II.6.8.1 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrograph of electrospun poly(α-hydroxy ester) fibrous scaffolds composed of randomly oriented ultra-fine fibers. (A) PGA; (B) PLGA5050; (C) PDLLA; (D) PLGA8515; (E) PLLA; and (F) PCL. Bar: 10 μm.

(Reproduced with permission from Elsevier B.V.)

FIGURE II.6.8.2 In vivo cartilage repair using engineered cartilage developed from chondrocyte-laden nanofibrous scaffold. Cultured chondrocytes were seeded into poly(lactic acid) nanofibrous scaffolds and cultured in a rotating wall vessel bioreactor. With the enhanced cell culture medium circulation, the cellular scaffold turned into a mature, functional cartilage implant after 42 days of culture. Artificially created cartilage defects of swine knees were successfully repaired by the engineered cartilage six months after surgery.

Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) or polyethylene oxide (PEO) – PEG or PEO is a non-biodegradable synthetic polymer that has been extensively used for cartilage tissue engineering. The major advantage of using PEG or PEO for scaffold fabrication is that the polymer can be functionalized to conjugate with a peptide or protein of interest to enhance chondrocyte activities or induce chondrogenesis. In addition, the polymer can be chemically modified to carry reactive groups, such as acrylates, that can be activated by high-energy light sources, and cross-linked to improve mechanical and degradation properties. Another desirable feature is that a modified PEG or PEO hydrogel mixed with therapeutic cells can be directly injected to fill irregular-shaped cartilage defects using a minimally invasive procedure (Elisseeff et al., 1999a). The minimally invasive implantation significantly reduces the time needed for the healing process.

For cartilage tissue engineering, dimethacrylate-functionalized PEO hydrogels mixed with chondrocytes were injected subcutaneously into mice and photopolymerized in situ using UV light (Elisseeff et al., 1999b). The results showed that chondrocytes in the solidified PEO hydrogel survived and actively produced cartilage matrix, and the regenerated neocartilage histologically resembled native cartilage. In addition, for the regeneration of healthy functional cartilage, PEG scaffolds have been designed to degrade at a controlled rate to free part of the scaffold space for natural ECM deposition. Functional groups, such as esters, can be chemically linked to unmodified PEG to improve biodegradation of the PEG hydrogel, since the ester linkage can be hydrolytically cleaved in culture medium (Bryant and Anseth, 2003). Various natural and synthetic polymers have also been grafted with PEG (Metters et al., 1999; Temenoff et al., 2002) to enhance cartilage-specific ECM production (Bryant and Anseth, 2003) and cartilage regeneration (Lee et al., 2003a; Wang et al., 2003).

Natural Biopolymers for Cartilage Tissue Engineering

Natural biopolymers, including protein-based and carbohydrate-based polymers, are derived from animals or plants, and have a long history of being used as biomaterials. The advantage of using natural biopolymers is that they have biofunctional molecular domains that can act to enhance cellular activities, such as cell adhesion and migration. On the other hand natural biopolymers for scaffolds also have drawbacks. They may have varying properties between different batches and may elicit immune response.

Protein-Based Materials

Collagen – Collagen represents the major protein type in the body, and has been widely used in various medical applications. Among the 29 identified collagen types, collagen type I is the most commonly used collagen for culturing chondrocytes (Fuss et al., 2000) or MSCs (Wakitani et al., 1994) in both in vitro and in vivo cartilage tissue engineering. Clinically, collagen type I, CaRes®, and collagen type I/III bilayer membrane, such as Maix® or Chondro-Gide®, have been approved to treat cartilage defects. Collagen types I and II have been compared in terms of their capability as a scaffold for cartilage repair (Frenkel et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2003b), and the results suggest that collagen type II is a more suitable scaffold material to maintain chondrocytic phenotype (Nehrer et al., 1997). However, in comparison to collagen type I, isolation and preparation of collagen type II in a sufficient quantity for scaffold fabrication is more challenging, because collagen type II is present exclusively in hyaline cartilage, whereas abundant collagen type I is found in many other tissues. As a biomaterial, collagen can be prepared in the form of a hydrogel, dehydrated porous sponge or electrospun fibrous structure for scaffold applications. Regardless of the structure type, the principal hurdle of using collagen matrices for cartilage tissue engineering is the short-term durability of the matrix, which reduces the structural stability of cell-seeded constructs during cartilage regeneration.

Fibrin – Fibrin, a component of the extrinsic coagulation cascade, is found commonly in blood clots. This biopolymer is an insoluble fibrillar protein converted from a soluble fibrinogen through the enzymatic activity of thrombin, and has been widely used as a clinical fixative or biological glue for many years, including recently as a biomaterial for cartilage tissue engineering. Specifically, it has been used as a glue to secure other scaffolds at the repair site, as a three-dimensional scaffold to culture chondrocytes (Silverman et al., 1999) and MSCs (Worster et al., 2001) for tissue regeneration, or as a carrier to deliver growth factors (Fortier et al., 2002) to facilitate cartilage repair. Like collagen, a fibrin-based glue, Tissucol®, is also approved to repair cartilage defects clinically. A previous study with 12-month post-surgery results showed more effective cartilage repair in patients implanted with fibrin embedded with autologous chondrocytes, compared to patients treated with a cartilage abrasion technique. Although the outcome appears promising, the inherent poor mechanical property and the immunogenicity of fibrin may limit its use in cartilage tissue engineering.

Silk fibroin – Fibroin, the principal component of insect silk, is another natural biopolymer that has recently been used in cartilage tissue engineering. Natural silks from different species, for example the spider or the silkworm, have different material properties, because the constituent silk fibroin can be arranged differently to construct different molecular structures. Owing to its considerable mechanical properties, silk holds great promise as a tissue engineering scaffold, particularly in a highly mechanically demanding tissue environment, because as that in cartilage. Silk fibroin has been made into a sponge scaffold to culture chondrocytes for rabbit cartilage repair, or fabricated into foam, microfibrous, or electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds to culture MSCs for both in vitro and in vivo cartilage tissue engineering.

Polysaccharide-Based Materials

Alginate – Alginate is a brown algae-derived carbohydrate polymer consisting of repeating L-guluronic acid and D-mannuronic acid. Alginate can be gelled in the presence of calcium or other divalent cations, and reversibly re-solubilized upon removal of the cations. In addition, alginate is capable of encapsulating cells in the matrix to maintain their spherical shape, which makes alginate a desirable scaffold for studying redifferentiation of chondrocytes (Liu et al., 1998), or promoting chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs (Caterson et al., 2001). Alginate scaffolds with varying stiffness can be fabricated by using different concentrations of alginate solutions or by varying cation concentrations during cross-linking (Kuo et al., 2001; 2008). By varying alginate concentration, mechanical properties of the resultant hydrogel can be significantly improved. However, the major concern with the use of alginate in cartilage tissue engineering is that the slow degradation of alginate often causes inappropriate immune response in vivo (Pier et al., 1994).

Agarose – Another carbohydrate polymer, agarose, is purified from brown seaweed, and contains a repeated disaccharide sequence of L- and D-galactose. Similar to alginate, the stiffness of the agarose hydrogel can be manipulated by varying its concentration. Dependent on the type and molecular weight, agarose gels have different solidification temperatures. By altering the temperature, agarose can change between a liquid gel form and a solidified structure form, which is a preferred property for convenient cell seeding. For cartilage tissue engineering applications, agarose has been extensively used as a three-dimensional scaffold to redifferentiate chondrocytes (Benya and Shaffer, 1982) or differentiate MSCs into chondrocytes (Fukumoto et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2004) ex vivo. However, the use of agarose for in vivo applications is limited by its extremely slow degradation rate (Cook et al., 2003) that could elicit foreign body giant cell reaction (Rahfoth et al., 1998).

Hyaluronic acid – The most widely used carbohydrate-based biopolymer in cartilage tissue engineering is hyaluronic acid. The biopolymer is a polysaccharide composed of repeating glucuronic acid and N-acetylglucosamine. Because hyaluronic acid is one of the major ECM components of cartilage, its use as a scaffolding material is biologically compatible for the activities of chondrocytes. Nevertheless, the applicability of native, unmodified hyaluronic acid is limited because the highly hydrophilic molecule is easily degraded in culture medium, and the hyaluronic acid gel does not possess sufficient mechanical strength. Therefore, a number of chemical modifications, including esterification (Campoccia et al., 1998) and other chemical cross-linking (Vercruysse et al., 1997), have been developed to improve its properties. For example, Hyaff 11® is a commercially available, three-dimensional structure based on an esterified derivative of hyaluronic acid, which exhibits improved degradation and mechanical properties, and has been used as a tissue engineering scaffold to seed chondrocytes and MSCs for cartilage tissue engineering (Facchini et al., 2006). A three-year clinical study using the esterified hyaluronic acid scaffold with autologous chondrocytes has shown satisfactory results on cartilage repair.

Chitosan – Chitosan is composed of repeating glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine disaccharides, and is derived from chitin, a type of polysaccharide commonly found in shellfish exoskeletons. Insoluble chitin becomes soluble chitosan after sufficient acetyl groups in a chitin polymer are removed. Because chitosan carries high cationic charges, it can interact with a variety of anionic polymers, such as chondroitin sulfate, to form a hydrogel (Denuziere et al., 1998). In addition, owing to its excellent biocompatibility and the ease of scaffold fabrication, chitosan is considered a promising biomaterial for cartilage tissue engineering. Chondrocytes cultured in a chondroitin sulfate-augmented chitosan hydrogel maintained their chondrocytic morphology and produced collagen type II (Lahiji et al., 2000; Sechriest et al., 2000). An in vivo study showed that chitosan injection effectively repaired defects of rat knee cartilage (Lu et al., 1999).

Chondroitin sulfate – Chondroitin sulfate is the major sulfated glycosaminoglycan of cartilage proteoglycan. Due to its excellent biocompatibility, and biological and functional roles in the cartilage ECM macrostructure (Bryant et al., 2004; Li et al., 2004), chondroitin sulfate has been shown to help wound healing and restore arthritic joint functions. Chondroitin sulfate monomers are commonly modified with methacrylate or aldehyde groups to produce reactive side-groups. With UV-activating these functionalized side-groups, a chondroitin sulfate gel can be solidified via photopolymerization. A number of in vitro studies have demonstrated the viability of encapsulated chondrocytes in the cross-linked chondroitin sulfate gel, suggesting potential applications for cell delivery to repair cartilage defects. To improve the stability of the chondroitin sulfate hydrogel in culture medium, non-biodegradable PEG (Li et al., 2004) or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) (Bryant et al., 2004) has been incorporated into chondroitin sulfate to produce a co-gel. Within the co-gel, the negatively charged chondroitin sulfate attracts water into the gel to create a swelling pressure that contributes to mechanical stiffness of the material, similar to that in native cartilage.

Advanced Scaffolds and Signaling Factors in Cartilage Tissue Engineering

Recent advances in the fields of material science, protein chemistry, control release, and nanotechnology have increasingly been applied to the development of cartilage tissue engineered scaffolds. These next generation biomaterial matrices, so-called “smart” scaffolds, are made of materials with a bio-inspired, functionalized surface, constructed of an ECM-mimetic structure, or capable of releasing biomolecules in a controlled release manner. The “smart” scaffold is designed to actively instruct cell behavior to facilitate cartilage regeneration.

“Smart” Scaffolds with Controlled Release Capability

One of the emerging research trends to enhance cartilage regeneration is the development of “smart” tissue engineered scaffolds with the capability of controlled release of growth factors, such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), that act to enhance matrix production of chondrocytes or induce chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs (Park et al., 2009). Delivery of growth factors can be achieved via biodegradation of scaffolding polymers, with the release kinetics of target molecules controlled as a function of the degradation properties of the polymer (Basmanav et al., 2008). Indeed, by using biodegradable polymers with differential degradation properties, it is possible to develop “smart” tissue engineered scaffolds capable of sequentially delivering different growth factors to enhance tissue regeneration (Yilgor et al., 2009). In addition to the capability of controlled release, the “smart” scaffolds should also function to protect delivered molecules from denaturation. Conventionally, growth factors are embedded in polymeric scaffolds by direct incorporation into a polymer solution during a fabrication process; however, scaffold fabrication usually involves organic solvents or chemical reactions that are likely to harm biological activities of to-be-delivered growth factors. Recently, several research groups have developed dual-structure scaffolds to protect bioactivities of delivered molecules by encapsulating the molecules with microparticles embedded in scaffolds (Holland et al., 2004).

Nanostructured Scaffolds with Biomimetic Architecture

In addition to biological signals, effective tissue engineering-based cartilage regeneration in ex vivo culture requires that scaffolds provide appropriate physical and chemical cues to guide cellular activities, such as cell differentiation and matrix production. Therefore, a biologically favorable culture environment must be used for effective cartilage regeneration. It is thus noteworthy that the size of the structural elements of a biomaterial scaffold have been proven to be crucial to cell activities. Recent studies (Webster et al., 2000; Dalby et al., 2002) have shown that cells cultured on substrates with varying topography exhibit different behaviors; a substrate composed of nanometer-scale components is biologically preferred. Among nanostructures, a nanofibrous structure composed of ultra-fine, continuous fibers feature the properties of high porosity, high surface area-to-volume ratio, and most importantly, morphological similarity to natural ECM, making it well-suited for tissue engineering applications (Li et al., 2002). To fabricate nanofibers, several fabrication approaches are available, and among these approaches, the electrospinning technique is considered a convenient and highly versatile approach. Electrospinning has been used for fiber production in the textile industry since 1934 (Formhals, 1934), and has recently been used for tissue engineering applications. Research evidence has shown that the unique physical features of electrospun nanofibers induce biologically favorable activities (Li et al., 2003), and nanofibrous scaffolds are ideal for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications (Li et al., 2009).

Ligament Tissue Engineering

Introduction to Ligament Tissue Engineering

Ligaments are a dense connective tissue between bony segments with specific macromolecular composition and arrangement, enabling a defined response to the unique loading state at each ligament. Their strength and elasticity permit our rigid skeletal frame to rotate around specialized joints and produce complex movements, while retaining mechanical stability. The normal response to load is nonlinear, anisotropic, and viscoelastic, with significant stress relaxation (Kwan et al., 1993) to slowly dissipate elastic energy (Hukins et al., 1990). A tear or dislocation in the tissue (Kennedy et al., 1974) or prolonged ligament immobilization (Woo et al., 1987) will compromise ligament function and joint stability, and result in a reparative response with subsequent scar formation. Several studies with animal models have demonstrated that injured ligaments do not recover normal mechanical properties, even after one year of healing (reviewed by Woo et al., 2006).

Clinical Relevance and Limitations of Current Repair Strategies

The poor healing ability of ligaments is compounded by the fact that ligament injuries are not rare, as an estimated 100,000 anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstructions are performed each year in the US (CDC, 1996), with injury rates among females between ages 14–17 increasing at the fastest rate (Csintalan et al., 2008). Thus there has been a tremendous effort among clinicians, scientists, and engineers to improve the rate and outcome of recovery after a ligament injury. There are three standard reconstructive treatments for serious ligament injury. For more than a decade, the most common surgical reconstruction technique for ligament injury has involved the transplantation of healthy autografted (self-donated) connective tissue, particularly patellar or semitendinosus-gracilis (hamstring) tendon tissue. This is not an ideal solution, since removal of local non-regenerative tendon tissue at the knee joint disrupts the normal biomechanical state, which has been found to require up to six months to recover to preoperative strength and endurance (Soon et al., 2004). Further, one study found that after seven years, knee flexibility, sensitivity, and laxity still remained significantly reduced (Lidén et al., 2007). Alternatives to autografting, such as allograft transplantation, for ligament reconstruction have been found to be more prone to rupture, and afford reduced functionality compared to autografts, mainly due to chemical treatments (Krych et al., 2008). Furthermore, concerns remain regarding potential immune reactions and disease transmission of untreated donated tissue. Finally, non-degradable synthetic polymer grafts made from materials such as polytetrafluorethylene or polypropylene have been found to suffer from mechanical problems, such as particle wear and failure rates on the order of 40–80%, primarily from fatigue rupture (Vunjak-Novakovic et al., 2004).

The Modern Ligament Engineering Strategy

Given these issues, there is a need for a treatment that could restore normal ligament function immediately, and retain or improve upon that level of function over the long term. We, and others, consider tissue engineering as an exciting alternative, offering the possibility of replacement with normal, living tissue. The modern ligament engineering strategy involves culturing cells of stem or fibroblastic phenotype onto a three-dimensional biodegradable scaffold, usually fibrous, and typically with a biochemical or physical stimulus to maintain or enhance ligament regeneration. Complex bioreactors have been developed that provide simultaneous dynamic fluid flow and cyclic tensile stimulation in heated and humidified environments. Central to the success of this strategy is the biomaterial which the cells are cultured on; the choice of biomaterial is important to the extent of cellular adhesion, initial scaffold strength and mechanical properties, scaffold degradation rate, and long-term implantation success. Tissue engineers generally obtain the best results when they design their regeneration strategy to mimic the tissue of interest, and thus it is critical to define and design for native ligament properties as summarized in the following section.

Native Ligament Macromolecular Composition and Structure

Ligament Composition

Ligaments derive their tensile strength and elasticity from the basic primary building block of their structure: collagen fibers. Collagen types I and III are primary constituents, along with elastin, and more minor proteins including fibronectin, decorin and tenascin. The mass ratios of these protein constituents to overall ligament mass depend upon location in the body, and vary especially with elastin content, which is most dense in ligaments that experience high tensile strains, such as spinal ligaments. The elastin affords greater flexibility (ductility) at the expense of strength, and also minimizes energy losses during elastic recovery, as exploited by some purely elastin ligaments found in cows and horses associated with grazing. Circumferentially oriented around the collagen fiber bundles are specialized elongated fibroblast cells, commonly referred to as tenocytes, which are responsible for maintaining the density and composition of the ligament matrix. The tenocytes adhere to the fiber bundles, and are surrounded by a glycosaminoglycan-rich matrix which enables fibers to slide along each other during bending, and also provides limited blood vessel and nerve supply. The neural innervations are primarily proprioceptive in nature, and act to provide feedback on the degree of joint flexion/extension.

Ligament Structure

Since ligaments are responsible for maintaining joint stability, their structure is designed to withstand high tensile loads. Beginning with a single triple-helical collagen molecule, the collagen molecules are organized in parallel nanometer-scale fibrils, and subsequently into micrometer scale fibers. The parallel collagen fiber matrix and surrounding proteoglycan-rich matrix reside in the middle zone, and resist tensile and sometimes simultaneous torsional loads, as seen in the anterior cruciate ligament (~90° twist). Within a few millimeters of bone, the ligament structure gradually becomes more bone-like, which is a critical region of normal function. The ligament insertion into bone, known as the enthesis, is typically described as a gradual, four-layer progression from non-calcified collagen fibers to fully calcified bone matrix. In-between are two layers of cartilaginous tissue containing fibrocartilagenous cells aligned with the collagen fibers, wherein the layer proximal to the bone contains calcium, and the layer proximal to the ligament does not.

Important Considerations of a Ligament Tissue Engineered Scaffold

Cellular Activity Requirements

One of the most important design considerations for ligament tissue engineering is that despite their white appearance, ligaments are not avascular tissues, and an active oxygen supply is critical for cell survival. This can be especially challenging, since ligaments must also be strong, stiff and elastic, often requiring densely packed natural or synthetic fibers. Additionally, tenocytes are natively distributed throughout the ligament both radially and longitudinally. The native long, spindle-like morphology of ligament cells is likely also important for normal genetic expression, and should be permitted by the scaffold geometry. The fabrication of three-dimensional scaffolds with fully distributed cells, and with adequate O2 supply, remains a formidable challenge in ligament tissue engineering, especially with ligament thicknesses greater than the oft-cited oxygen diffusion limit of 200–300 μm. Several authors have been actively addressing these cellular activity requirements, which will be discussed in upcoming sections.

Material Property Requirements

In addition to cellular activity requirements, there are four principal material property requirements for engineering ligaments. First, the material must enable cellular adhesion and proliferation, and must not be cytotoxic or immunogenic to attached cells, local surrounding tissues or the overall body. Second, the scaffold material should have an architecture that enables full cellular distribution, additional tissue ingrowth (e.g. endothelial or connective), and is biomechanically capable of resisting major planes of stresses expected to be seen in vivo. Third, the material must possess adequate elastic modulus, strength, and ductility, especially under tension, and should also have similar viscoelastic properties to native ligament. Mechanical mismatches are particularly important since ligament is a loadbearing tissue; they can result in scaffold rupture (too weak), stress-shielding effects where local connective tissues begin to atrophy (too strong) or joint laxity and energy imbalances (potentially from incorrect viscoelasticity). Finally, the material should biodegrade without toxic byproducts at a rate that is equal to the rate of tissue formation, and ideally be completely eliminated from the body at a time coincident with full ligament regeneration.

While at present no material or system has met all of these requirements, they have been actively investigated through a number of different single and composite material approaches using synthetic and natural biopolymers, as reviewed in the following paragraphs.

Biomaterials in Ligament Tissue Engineering

Synthetic Biomaterials in Ligament Tissue Engineering

An ideal engineered ligament would contain enough starting material for immediate loadbearing post-implantation, and would degrade at a rate comparable with that of developing cellular and tissue ingrowth. After a period of several weeks or months the starting material, or scaffold, would be completely replaced by regenerating ligament cells and matrix. The requirement for biodegradability and fabrication into specific ligament-like geometries has generated interest in the use of synthetic polymer materials for ligament tissue engineering, dating back to at least 1999 (Lin et al., 1999).

Polyhydroxyesters degrade by hydrolysis, and thus have been very popular for ligament tissue engineering because the degradative molecule, H2O, is naturally present in abundance in vivo. An early cell attachment study by Ouyang et al. (2002) found that on two-dimensional matrices anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)-derived fibroblasts adhered and proliferated on PCL, PCL/PLA (50:50), and PLGA (50:50) substrates at a rate that was not significantly less than tissue-culture plastic (O2-plasma treated polystyrene). However, high hydrophilicity of certain polyhydroxyesters is thought to be detrimental to general cell adhesion (van Wachem et al., 1985), and hence it is regarded that a balance of hydrophobic and hydrophilic components should be considered for ligament tissue engineering. Several studies have utilized these findings, and extended ligament cell culture into three dimensions by fabricating ligament-like polyhydroxyester scaffolds, several of which are reviewed here.

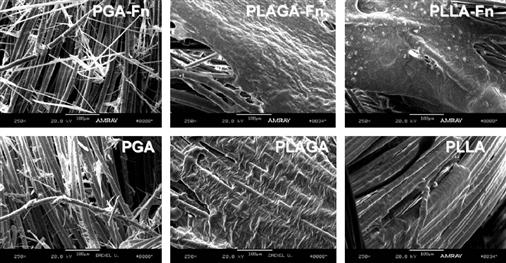

Lu et al. (2005) fabricated three-dimensional braided scaffolds of PGA, PLGA, and PLLA filaments at two levels of bundling using a circular braiding loom designed to mimic the hierarchical structure of native ligament. To improve cellular adhesion, these investigators modified the surfaces by immersing the scaffolds in a solution of human recombinant fibronectin (Fn). Ligament cells were isolated from rabbit ACL tissue by digestion in collagenase, and grown to confluence before being added to the scaffolds. After 14 days of culture, using scanning electron microscopic analysis it was found that cells seeded on PLLA-Fn and PLAGA-Fn scaffolds produced the most matrix, and that PGA was detrimental to matrix formation, owing to rapidly produced acidic byproducts (Figure II.6.8.3).

FIGURE II.6.8.3 ACL fibroblast growth and matrix formation on different synthetic braided scaffolds visualized with SEM (Lu et al., 2005). Images were taken after 14 days of in vitro culture in 10% fetal bovine serum. (Left) Culture with PGA resulted in substantial matrix degradation from acidic byproducts. (Middle)-co-glycolic acid (PLAGA) in an 82:18 mass ratio showed more sustainable matrix formation, particularly with the addition of fibronectin (Fn). (Right) PLLA scaffolds also displayed considerable matrix formation, which again was amplified by the addition of Fn.

(Reproduced with permission from Elsevier B.V.)

Furthermore, PGA-Fn had significantly reduced cell numbers compared to PLAGA-Fn and PLLA-Fn scaffolds, which were not significantly different from each other. The authors concluded that both the PLLA-Fn and PLAGA-Fn scaffolds would be effective for ligament tissue engineering, but acknowledged that the PLLA-Fn scaffolds may be the more appropriate choice because of their slower degradation rate. A study of the tensile properties of braided PLGA 10:90 scaffolds found ultimate tensile strengths in the range of 100–400 MPa, and with a circular braiding scheme a maximum load of over 900 N, both of which were considered practical and safe for initial implantation in a human ACL replacement surgery (Cooper et al., 2005). Recent work has also elucidated ideal braiding angles of these scaffolds to most accurately mimic the non-linear stress–strain relationship of native ligament (Cooper et al., 2007). Taken together, these studies show great promise for future use of braided synthetic scaffolds for ligament replacement, particularly if the degradation profiles are optimally balanced against tissue ingrowth using an animal model.

PLGA 10:90 scaffolds have also been fabricated with collagen type I to form porous, rolled microsponges for ligament tissue engineering (Chen et al., 2004). These hybrid scaffolds were considered advantageous because of the combined cellular binding affinity and mechanical strength afforded by collagen and PLGA, respectively. To fabricate the microsponges, the PLGA was immersed in a solution of bovine collagen type I, freeze-dried, and cross-linked with glutaraldehyde (unreacted aldehyde groups were blocked with glycine). In this study, ligament cells were isolated from beagle ACL samples with collagenase and cultured for 16 days in vitro before rolling and subcutaneous implantation into nude mice. Using paraffin sectioning with hematoxylin and eosin staining, coupled with SEM, the authors concluded that cells were viable in the scaffold even after 12 weeks of implantation, and that the hybrid scaffolds may be appropriate for ligament tissue engineering.

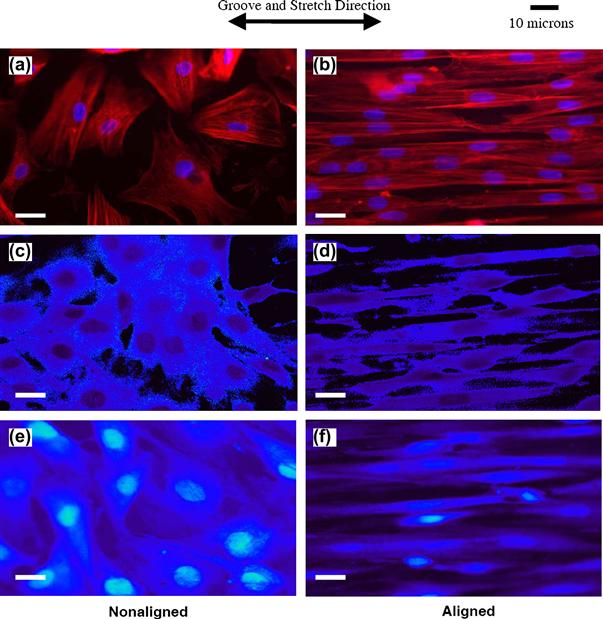

One of the advantages of synthetic polymers is that they can be processed relatively easily into fibers with nanometer-scale diameters – on the order of native collagen fibrils. As presented earlier, nanofibers are typically fabricated using the 70+ year old electrospinning process, which utilizes an electric field (typically kV potentials over ~5–20 cm) to overcome surface tension of a viscous polymer solution and form a chaotic nanodiameter polymer jet that is deposited onto a surface of interest (Pham et al., 2006). Lee et al. (2005) produced aligned polyurethane nanofiber scaffolds with average fiber diameter of 650 nm and 82% porosity using an electrospinning apparatus and a rotating collector target. Seeded human ligament cells were cultured for 48 hours then subjected to 5% uniaxial strain at 0.083 Hz using vacuum flexion on a silicone membrane for an additional 24 hours. It was demonstrated that cells seeded onto aligned scaffolds produced significantly more collagen mass per cell of DNA, compared to randomly oriented fiber controls, and that the aligned nanofibers enabled cell morphologies most comparable with in vivo morphology. This study was one of several demonstrating the potential applicability of aligned nanofibers for ligament tissue engineering. Composite nanofiber and microfiber scaffolds have also been fabricated for ligament tissue engineering (Sahoo et al., 2006). In this study, electrospun PLGA (65:35) nanofibers with 300–900 nm diameter range were deposited onto a mesh of 25 μm diameter PLGA (10:90) microfibers producing scaffolds with 0.8–1.3 mm thickness and 2–50 μm pores (evaluated with SEM). The rationale for this system was that the microfibers would provide mechanical strength and degradation resistance, and the nanofibers would provide hydrophilicity and a very high surface area for optimal cell attachment. The authors seeded porcine bone-marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), and observed an average collagen production of 1.55 ng/cell after seven days, which was considered high relative to previous studies with other scaffold geometries. Furthermore, mRNA expression levels of critical ligament genes, including collagen type I, decorin, and biglycan relative to the GAPDH housekeeping gene, were all slightly upregulated (5–20%), suggesting partial differentiation into ligament lineages. The authors acknowledged, however, that the ultimate tensile strengths and failure loads were still far below those of native ligament, and that it was difficult to have confidence that the cells were directed into ligament lineages. Nevertheless, the high level of matrix production demonstrates the potential of the method, and a follow-up study (Sahoo et al., 2007) reports further optimization of these scaffolds using surface modifications including PCL and collagen type I deposition to enhance cell attachment and proliferation, and also a right-angle fiber weaving method to increase failure load by ~50% over knitted fabrication.

These studies demonstrate some of the advantages imparted by synthetic nanofiber technologies for ligament tissue engineering, which will continue to expand and evolve as more specific ligament cell–nanofiber interactions are elucidated. At present, it appears that most studies show results favoring aligned nanofibers over randomly oriented fibers, likely due to their resemblance to native ligament fibril orientation, but the ideal fiber materials, diameters, spacing, and angles remain unresolved for ligament tissue engineering. Currently, a single material is typically used, but the opportunity exists to incorporate fibers of different diameters and mechanical properties into a single aligned scaffold in an effort to mimic the multi-protein matrix of ligament, e.g., collagen type I, collagen type III, and elastin. Finally, the rapid degradation rate of synthetic nanofibers must be controlled, and perhaps decelerated, before in vivo implantation will be feasible. Overall, however, synthetic nanofiber scaffolds are cytocompatible and have tailorable diameters and degrees of alignment, and are one of the most exciting prospects for the design of engineered ligaments.

Natural Polymeric Biomaterials in Ligament Tissue Engineering

We have seen that synthetic polymeric biomaterials have reproducible mechanical and chemical properties, are easily fabricated into different shapes and sizes, degrade by hydrolysis, and are efficacious for ligament engineering research. However, they may lack functional chemical groups for cellular binding, and furthermore they may release acid byproducts or unnatural polyesters into the bloodstream during degradation. For these reasons there has been considerable interest in the application of natural, protein-based fiber materials as scaffolds for ligament tissue engineering. The most direct and obvious choice for this material is collagen type I, because of its prevalence in ligament tissues. Unfortunately, no method yet exists to organize and cross-link collagen fibers in a cytocompatible manner, and as such collagen gels remain exceptionally weak with typical elastic moduli between 10–30 kPa and ultimate tensile strengths between 5–10 kPa (Roeder et al., 2002). Thus, collagen-based scaffolds, while useful to investigate mechanisms of tendon differentiation and regeneration (Kuo and Tuan, 2008), are challenging to be used for ligament replacement.

Silk fibroin, rather than collagen, has been the most popular natural polymeric biomaterial for ligament tissue engineering. Silk fibroin is one of two proteins excreted by Bombyx mori silkworms during cocoon production, and is typically isolated from its sister protein sericin using sodium carbonate, urea, and/or soap detergents and near-boiling temperatures (Yamada et al., 2001). B. Mori silk fibroin is 70–80% by mass of the silk bicomplex (Kato et al., 1998), contains a heavy (350 kDa) and light chain unit (25 kDa), and is held together by the sticky sericin protein, which unfortunately is cytotoxic. The principal advantage of silk is its remarkable tensile strength and toughness (area under stress–strain curve) which is unmatched for natural proteins. Reported tensile mechanical properties of B. Mori silk fibroin range between 5–9 GPa for elastic modulus, 250–400 MPa for tensile strength, and 23–26% for failure strain (Jiang et al., 2006). The protein also displays surface amino acids for cell adhesion, remains structurally whole in aqueous solutions but slowly degrades (weeks–months) proteolytically in vivo (Minoura et al., 1990; Greenwald et al., 1994), and can be fabricated into gels, films, braided fibers or nanofibers. These characteristics make silk fibroin one of the best natural polymers for support of cellular and tissue ingrowth for tissue engineering.

Silk fibroin has been used for several decades as a suture material because of its strength and slow biodegradability, and since at least 2002 has been considered for ligament tissue engineering. Altman et al. (2002a) were one of the first to design a braided silk fibroin scaffold and test for adherence, proliferation, and genetic expression of seeded bone-marrow derived MSCs. A braided geometry with four levels of bundles twisted with 0.5 cm pitch was chosen to effectively reduce the linear stiffness of a single fiber, to better model native ACL stiffness and minimize stress-shielding effects. To model physiological performance a 400 N cyclic load was applied to a 3.67 mm diameter scaffold (designed to fit a human knee bone tunnel), and a subsequent fatigue analysis with linear extrapolation indicated a matrix life of 3.3 million cycles, which was expected to far outlast in vivo degradation. After 14 days of in vitro culture with human MSCs, the authors found that DNA content (and thus cell number) increased five-fold compared to 24 hours of culture; this was complemented by scanning electron microscopic analysis showing considerable matrix deposition over the culture period. Furthermore, mRNA expression levels of ligament-associated genes were comparable to those in native human ACLs, especially an average collagen type I to type III ratio of ~9, an absence of collagen type II and bone sialoprotein (which would indicate cartilage or bone differentiation, respectively), and baseline expression of the tendon/ligament marker tenascin-C. The success of this initial work was considerable and highlighted the potential applicability of silk fibroin that has been properly processed and organized for in vivo ligament replacement. It also led to several modifications, optimization studies, and in vivo evaluation studies for utilizing silk fibroin in ligament tissue engineering, several of which are reviewed below.

Scaffold geometries other than braided structures have also been fabricated with silk fibroin. Liu et al. (2008) surmised from previous studies of synthetic braided ligaments that such braided structures may have limited nutrient diffusion and tissue infiltration, particularly towards the center on the radial axis. To circumvent this potential issue, the authors fabricated a silk fibroin hybrid scaffold with geometries at two levels – a knitted scaffold and an interspersed microporous silk sponge. The knitted scaffold was fabricated using a 40-needle knitting machine, and the sponge was added by immersing the knitted scaffold in a low concentration silk solution, freeze-drying to form pores, and then immersing in a methanol solution to prevent resolubilization. Human MSCs were seeded by pipetting onto knitted-sponge or knitted-alone scaffolds, with unseeded scaffolds as a secondary control and a total culture time of 14 days. Compared with knitted scaffolds alone, the knitted-sponge scaffolds showed significantly higher biological responses with nearly every evaluation method, including cellular proliferation, GAG production, viable cell density, mRNA expression of collagen types I and III, and tenascin-C, and collagen-based matrix production, confirming the positive benefit of the microporous silk sponge. However, no significant differences in maximum tensile load or stiffness were recorded compared to unseeded scaffolds after 14 days, suggesting that the secreted matrix did not contribute towards scaffold strength. Also, the tensile strength and stiffness were far below (<20%) those of the adult human ACL (Woo et al., 1991). Nevertheless, the cytocompatability and rapid ligament-like matrix development is impressive, and further demonstrates the effectiveness of a cyto-friendly composite structure. With the design of a stronger starting matrix, the knitted-sponge scaffold may be an attractive candidate for in vivo ligament replacement, conferring rapid tissue regeneration and (importantly) initial tensile strength.

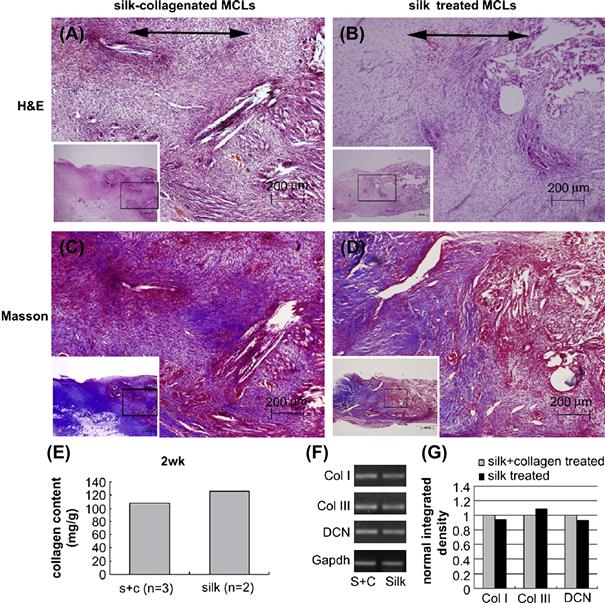

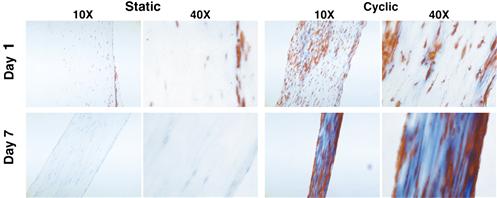

In addition to synthetic scaffolds, multi-material or composite natural scaffolds have also been successfully fabricated for ligament tissue engineering applications (Chen et al., 2008). In this work a knitted silk-fibroin base matrix was infiltrated with a freeze-dried collagen type I microsponge creating a similar composite structure to that used by Liu et al. (2008), but with a collagen type I sponge instead of a silk sponge. MSCs were seeded into the scaffolds which were then implanted into a rabbit medial cruciate ligament (MCL) transection model to evaluate in vivo repair potential over a total of 12 weeks. In vitro, the authors found that gene expression levels of ligament-associated genes by cells seeded in silk–collagen scaffolds compared to silk alone were considerably higher, with collagen type I elevated by 250%, and decorin elevated by over 500%. Histological analysis with H&E and Masson’s trichrome staining of the repairing MCL found more tissue ingrowth compared to silk alone and untreated MCLs after 2, 4, and 12 weeks; Figure II.6.8.4 shows the repair results after 14 days of implantation.

FIGURE II.6.8.4 Histological and gene expression analysis of the extent of in vivo repair after 14 days using silk and silk/collagen scaffolds in a rabbit model of MCL transection by Chen et al. (2008). (A,B) H&E staining showed relatively unorganized matrix formation but a higher cell density in silk/collagen scaffolds than silk alone. (C,D) Masson’s trichrome staining revealed the beginnings of collagen fiber formation (indicated by blue areas), and more collagen deposition in the silk/collagen scaffold group. (E) Total collagen content was reduced in the silk/collagen group (S + C), but, as detected by RT-PCR (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction) shown in (F,G), this could have been due to a reduction in the expression of collagen type III, a less appropriate collagen type for the ligamentous phenotype than collagen type I and decorin, both of which are showing higher levels of expression in the silk/collagen scaffold group.

(Reproduced with permission from Elsevier B.V.)

In addition, the mean collagen diameter of the repaired region observed with transmission electron microscopy was closer to that of native ligament (~65 nm). Although the mechanical properties of the repair tissue were considerably less than those of native MCL, the results suggest that a silk and collagen sponge matrix may be an effective treatment for MCL transections, particularly because of its support of rapid tissue ingrowth. Future anlaysis comparing in vitro and in vivo repair between knitted silk scaffolds, with either a collagen type I sponge or silk-fibroin sponge, would provide additional information for the optimization of sponge pore size.

One of the most important evaluation tests in ligament engineering is the success of an engineered graft to be regenerated by the body into a functional ligament. Recent studies by Fan et al. have investigated silk scaffold ligament regeneration in rabbit (Fan et al., 2008) and pig models (Fan et al., 2009), providing new insights into the kinetics of ligament tissue ingrowth and scaffold degradation. First, a rabbit ACL reconstruction model was tested by transecting healthy rabbit ACLs and surgically implanting an MSC-seeded knitted silk scaffold with microporous silk sponge. In vitro, cells were seeded onto the silk grafts for an eight-hour adhesion time before implantation by anchoringinto bone tunnels of rabbit knees. A morphological and histological evaluation of implanted silk grafts replacing the rabbit ACL after eight weeks suggested substantial production of collagen type I, collagen type III, and tenascin-C, and that the ligament–bone attachment was stable (evaluated with micro-CT). Similar to other studies with knitted silk scaffolds, the tensile strength and stiffness were unfortunately below those of native human ACL. A subsequent study using the larger porcine model showed similar encouraging results. To compensate for the additional loadbearing, the knitted-sponge silk scaffold was rolled around a braided silk cord and again was seeded with MSCs for eight hours before implantation. After 24 weeks, the gross morphological and histological characteristics were evaluated and as before, collagen type I, collagen type III, and tenascin-C were all distinctly present, as seen by immunohistochemistry. However, with an average failure load of 398 N, the authors noted that regenerated scaffolds at 24 weeks could be effective for mild daily loadbearing, but would likely not survive trauma or vigorous exercise. Unfortunately, the scaffold strength at earlier time points was not measured; it is clear, however, that 24 weeks would likely be too long for most patients to wait before mild loadbearing would be feasible. Nevertheless, the clinical implications of this study are profound, and demonstrate the in vivo effectiveness of a multi-structural silk scaffold for ligament tissue engineering.

Because of their inherent biocompatibility, natural polymeric macromolecules will likely remain at the forefront of biomaterials for ligament tissue engineering. Although collagen type I gels may eventually be the scaffold material of choice, their ultimate tensile strength and elastic modulus are currently too low to act as a loadbearing material. In the interim, silk fibroin has emerged as an excellent natural biomaterial alternative to collagen, and has already been shown to regenerate ligament in large-scale animal models. Assuming the success of longer-term animal trials, it is anticipated that impending clinical trials with silk fibroin-based engineered ligaments will confirm the efficacy of silk to restore ligament function after injury, and offer exciting new options for ACL or general ligament repair.

Advanced Scaffolds and Signaling Factors in Ligament Tissue Engineering

Functionalized Ligament Scaffolds

One of the key factors in effective application of material scaffolds in tissue engineering is the optimization of cell–biomaterial interactions, particularly in terms of the ability of cells to adhere, proliferate, and secrete matrix onto the scaffold. Synthetic and natural polymers are effectively long chains of repeating chemical units, and it is thus possible to link small molecules covalently to their surfaces to enhance cell adhesion, proliferation, and matrix production. Such an approach has high potential, since biomaterials that natively lack chemical cell attachment groups can also be functionalized, thus expanding the range of implantable biomaterials. Cell–matrix interactions are typically mediated via cell surface integrin receptors, which are specialized transmembrane proteins that are connected cytoplasmically to the actin cytoskeleton. The most common example of an integrin-interacting matrix epitope is the peptide sequence, RGD (arginine–glycine–aspartic acid) (Orlando and Cheresh, 1991), which has been used to functionalize a number of biomaterials.

The practice of functionalizing grafts to improve engineered tissues is sometimes done passively by merging one scaffold with another for the purpose of combining mechanical properties with integrin-binding capability. An example of passive functionalization is a recent work by Garcia-Fuentes et al. (2009) who blended hyaluronan, a common native glycosaminoglycan, with silk fibroin and seeded MSCs for general regenerative applications. Matsumura et al. (2004) conducted a more direct functionalization study, and modified polyethylene-co-vinyl alcohol (PEVA) films with carboxyl groups (COOH) and subsequently covalently attached collagen type I, designed to enhance periodontal ligament adhesion to PEVA-coated titanium dental implants. Other general tissue engineering applications have used a variety of functionalizing groups, including phosphate (PO43−), amide (R1(CO)NR2R3) and sulfonate groups (RSO2O−).

There has been some interest in adding functional groups to non-degradable synthetic graft surfaces in the hope of enabling tissue growth and avoiding poor tissue integration, foreign body immune responses, and high failure rates. Zhou et al. (2007) functionalized polyethylene terephthalate (PET) grafts with poly(sodium styrene sulfonate) (PNaSS) functional groups and observed fibroblastic cell response. PET is used for an array of commercial applications including containers, water bottles, polar fleeces, and wind sails, and does not degrade in vivo. These investigators functionalized PET by first exposing PET fabrics to ozone gas (O3), which is unstable and breaks into O2 and O·, the latter of which transfers its free radical to the PET surface making it much more reactive. Under an inert argon atmosphere, the samples were then immersed in a bath of monomer 15% w/v sodium p-(styrene sulfonate) (NaSS) at 65–70°C, forming polyNaSS on the PET surface by radical polymerization. The human fibroblast McCoy cell line was seeded onto the functionalized PET surface and observed after four days of culture with calcein AM, a fluorescent label that is only retained inside living cell membranes. Captured images revealed considerably more cell adherence onto functionalized fibers than non-functionalized fibers. Additionally, dynamic fluid testing indicated that cells adhered to polyNaSS-PET scaffolds compared to PET alone required 12-fold more shear stress for 50% of the adhered cells to be removed (12 dyn/cm2 compared to 1 dyn/cm2). The authors attributed these profound results to two factors: the enhanced surface hydrophilicity enabling cell spreading; and the opportunity for fibronectin to bind to the PNaSS, increasing the number of focal adhesion contacts and the potential for organized cytoskeletal formation. It will be particularly interesting when these functionalized grafts are implanted in vivo to test if the foreign body capsulation response is still present, and if not, how they perform over long-term implantation.

Decellularized Ligament Scaffolds

It has been argued that the best replacement biomaterial for ligaments is those derived from the ligaments themselves (when they are available), because the tissues already have ideal mechanical properties and because the endogenous integrin-binding sites are abundant and present in the native ECM. However, some studies have suggested that allograft tissues can contain residual donor cells, even with strict sterilization and cleaning (Zheng et al., 2005), and may cause significant inflammatory response when implanted in vivo (Malcarney et al., 2005). Furthermore, there are concerns about the extent and efficiency of cellular infiltration, particularly to the dense center areas of the graft. Thus, the application of chemical treatments to yield a fully decellularized and more porous scaffold, as opposed to the use of minimally treated allografts (Musahl et al., 2004), is preferred for ligament tissue engineering. Whitlock et al. (2007) recently addressed this issue with a novel oxidative chemical treatment and a battery of in vitro cytocompatibility and tissue tests. The authors isolated adult chicken flexor digitorum profundus tendons and added 1.5% peracetic acid to act as an oxidizing agent (using OH radicals) to create pores in the tissue and remove loose DNA. Simultaneously, the detergent Triton™ X-100 (polyethylene glycol octylphenyl ether) was also added at 2% concentration to lyse cell membranes. When compared to non-treated controls, the oxidized scaffolds had no nuclei visibly present (H&E, DAPI staining), and at minimum 70% less total DNA, which was considered a very promising result. The scaffolds also appeared much more porous, as observed by SEM, and on average had 25% less elastic modulus and stiffness, which was not statistically significant. Results from a subcutaneous rat in vivo cell infiltration study showed that after three weeks, cell nuclei were present in the outside layers and some inner layers of the scaffold, and no inflammatory reaction or capsule formation was present. Future studies with human ligament allografts utilizing a combination of a lysing agent and oxidative agent are warranted, and these treatments may prove to be effective in minimizing the foreign body and capsulation responses found with standard allografts.

The Effects of Growth Factors on Natural and Engineered Ligaments