Chapter III.1.5

Implant Retrieval and Evaluation

Introduction

Implant retrieval and evaluation is a term used to describe a method of scientific analysis designed to determine the efficacy and safety or biocompatibility of biomaterials, prostheses, and medical devices in vivo. A key objective of this process is to determine if a medical device and its constituent biomaterials present potential harm to the patient. Implant retrieval and evaluation addresses the effects of both the recipient on the implant, and the implant on the recipient, especially biocompatibility, in the context of existing pathology. Implant retrieval and evaluation methodology is used to analyze an individual implant in the context of surgical removal or autopsy from a particular patient, or as an analysis of a collection of implants of a given generic type or a specific model of a device. When properly done, comprehensive analysis of cohorts of implants of similar types reveals paradigms of success as well as failure.

Implant retrieval and evaluation, both preclinical (animal) and clinical (humans), provides the opportunity to identify the modes, interactions, and mechanisms that lead to the success or failure of medical devices under end-use conditions. Appropriate implant retrieval and evaluation requires the development of a multilevel strategy to address device-specific parameters, the role of the patient, and device–patient interactions that lead to implant failure. Implant retrieval and evaluation is at its best highly structured and multidisciplinary, requiring the expertise and experience of scientists, engineers, and clinicians.

In this chapter, implant retrieval and evaluation are considered from the perspective of ultimate human clinical use. Therefore, this chapter draws upon many important perspectives presented in chapters dealing with materials science and engineering, biology, biochemistry, and medicine, host reactions and their evaluation, the testing of biomaterials, the degradation of materials in the biological environment, the application of materials in medicine and dentistry, the surgical perspective of implantation, the correlation of material surface properties with biological responses of biomaterials, and failure analysis (as discussed in Chapter III.5.3). Although this chapter focuses on implant retrieval and evaluation in the clinical environment, many of the goals and perspectives presented are important, and largely identical, to those used in preclinical (i.e., animal) investigation. Emphasis will be on the appropriate rationale and overall contributions of hypothesis-driven explant analysis applicable to failed as well as nonfailed and, in some situations, unimplanted devices. In this chapter, implants are considered to be composed of one or more biomaterials that are part of a specific design for a specific application. For these purposes, implants are prostheses, medical devices, or artificial organs.

Goals

The general concept of implant retrieval in the context of clinical device use is presented in Figure III.1.5.1. Key factors determining the outcome of a medical device are the biomaterials and device design, patient-specific functional anatomy and pathology, and technical aspects of the implantation. An implant is placed in a patient by a surgeon. The term “surgeon” is broadly used here to include also “interventionalists” such as cardiologists or radiologists, etc., who implant devices through catheters or cannulas. Through device selection, implantation technique, and implant manipulation during the insertion procedure, the surgeon potentially has considerable impact on the success or failure of a device. This feature constitutes a key difference between devices and drugs (the efficacy and safety of the latter generally are not affected by the process of insertion per se). All implants have interactions of the constituent biomaterials with the surrounding tissues. These interactions may be local at the site of implantation or distant from the device, and their mechanisms may be elucidated by careful and appropriate study. Clinically important deleterious biomaterials–tissue interactions manifest in a patient as complications. Implants are retrieved after successful function or failure by either surgical removal (at reoperation) or autopsy (by consent of the next-of-kin obtained after the patient’s death). However, conventional autopsy permission and procedures generally do not permit destructive examination of the extremities or face. The information derived from implant retrieval and evaluation is frequently used to guide development of new, and modification of existing, implant designs and materials, to assist in decisions of implant selection, and to otherwise alter the management of patients (such as anticoagulation drug regimens for prosthetic heart valves, activity limitations for patients with prosthetic joints, or periodic imaging of an operative site).

FIGURE III.1.5.1 Role of implant retrieval and evaluation in the development and use of clinical devices.

The general goals of retrieved implant evaluation are presented in Table III.1.5.1. While many implant failures can be characterized as implant- or material-dependent or clinically- or biologically-dependent, many modes and mechanisms of failure are dependent on both implant and biological factors (Schoen and Levy, 2005; Goodman and Wright, 2007; Burke and Goodman, 2008; Revell, 2008a,b).

TABLE III.1.5.1 General Goals of Implant Retrieval and Evaluation

Determine rates, patterns, and mechanisms of implant failure

Identify effects of patient and prosthesis factors on performance

Establish factors that promote implant success

Determine dynamics, temporal variations, and mechanisms of tissue–materials and blood–materials interactions

Develop design criteria for future implants

Determine adequacy and appropriateness of animal models

To appropriately appreciate the dynamics and temporal variations of tissue–materials and blood–materials interactions of implants, a fundamental understanding of these interactions is important. Appropriately conceived, structured and implemented, implant retrieval and evaluation should elucidate materials, design, and biological factors in implant performance, and enhance design criteria for future development. Finally, implant retrieval and evaluation should offer the opportunity to determine the adequacy and appropriateness of animal models used in preclinical testing of particular types of implants and biomaterials.

The goals of routine hospital surgical pathology or autopsy examination of a prosthetic device are generally restricted to essential documentation that a specific device has been removed at reoperation or that the patient died with the device, and diagnosis of a clinical abnormality that required the original therapeutic intervention or was a major complication of the device. Detailed correlation of morphologic features with clinical signs, symptoms, and dysfunctional physiology is usually not performed. Indeed, few pathologists have appropriate training, motivation and necessary resources to do complete and sophisticated analysis of retrieved implants. Nevertheless, directed and informed pathological examination of prostheses retrieved during preclinical animal studies or at reoperation or autopsy of human patients can provide highly valuable information. First, preclinical studies of modified designs and materials are crucial to developmental advances for technological innovation in biomaterials and medical devices. These investigations usually include implantation of functional devices in the intended location in an appropriate animal model, followed by noninvasive and invasive monitoring, followed by specimen explantation, and detailed pathological and material analysis. Second, for individual patients, demonstration of a propensity toward certain complications (e.g., a genetic propensity toward thrombosis) could have great impact on further management. Third, clinicopathologic analysis of cohorts of patients who have received a new or modified prosthesis type evaluates device safety and efficacy to an extent beyond that obtainable by either in vitro tests of durability and biocompatibility or preclinical investigations of implant configurations in large animals. Moreover, through analysis of rates and modes of failure, as well as characterization of the morphology and mechanisms of specific failure modes in patients with implanted medical devices, retrieval studies can contribute to the development of methods for enhanced clinical recognition of failures. The information gained should serve to guide both future development of improved prosthetic devices to eliminate complications, and diagnostic and therapeutic management strategies to reduce the frequency and clinical impact of complications. Emphasis is usually directed toward failed implants; however, careful and sophisticated analysis of removed prostheses that are functioning properly is also needed. Indeed, detailed analyses of implant structural features prior to, and their evolution following, implantation can yield an understanding of structural correlates of favorable performance, and identify predisposition to specific failure modes, which can be extremely valuable.

Device retrieval analysis has an important regulatory role, as specified in the US Safe Medical Devices Act of 1990 (PL101–629), the first major amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act since the Medical Device Amendments of 1976. The user requirements of the 1990 legislation require health care personnel and hospitals to report (within 10 days) to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or manufacturers or both (depending on the nature of the occurrence) all prosthesis-associated complications that cause death, serious illness or injury. Such incidents are often discovered during a pathologist’s diagnostic evaluation of an implant in the autopsy suite or the surgical pathology laboratory.

Implant retrieval and evaluation programs may also provide specimens and data that serve as a teaching or research resource. The information gained can be used to educate patients, their families, physicians, residents, students, engineers, and materials scientists, as well as the general public. As a research resource, implant retrieval and evaluation yields data that can be used to develop and test hypotheses, and to improve protocols and techniques.

Components of Implant Retrieval and Evaluation

Implant retrieval and evaluation is a structured, multifaceted, and interdisciplinary effort by scientists with expertise in materials science, materials engineering, biomechanics, biology, pathology, microbiology, radiology, medicine, and surgery (Table III.1.5.2).

TABLE III.1.5.2 Important Components and Features of an Implant Retrieval and Evaluation Program

Entire activity is hypothesis-driven

Specimens are appropriately accessioned, cataloged, and identified

Known and potential failure modes are thoughtfully considered

Patient’s medical history and laboratory results are reviewed

Data are collected on well-designed, study-specific forms

Careful gross examination, photography, and other basic analyses are always done

Advanced analytical techniques done by specialists are considered in selected cases

Analytical protocols and techniques for assessing host and implant responses are rigorously followed

Correlations and cause-and-effect relationships among material, design, mechanical, manufacturing, clinical, and biological variables are sought

Quantitative data are collected wherever possible and appropriate

Statistical and multivariant analyses are used

The first component is the appropriate accessioning, cataloging, and identification of retrieved implants. Patient anonymity∗ is required in any implant retrieval and evaluation program, and this can be achieved through appropriate accessioning, cataloging, coding of demographic information, and restriction of access. At most institutions, implant retrieval is carried out through the Surgical Pathology and Autopsy Services of the hospital.

As an example the Implant Retrieval and Evaluation Program at University Hospitals of Cleveland Case Medical Center uses the general accessioning and cataloging scheme for surgical pathology specimens. Gross and microscopic diagnoses in a standardized format are provided for patient’s charts, for the appropriate clinicians and surgeons, and for the database for the Implant Retrieval and Evaluation Program. The Department of Surgery provides specimens to the Division of Surgical Pathology, with the patient’s name and hospital identification number, clinical diagnoses, and notes on the patient and/or implant history.

An in-depth evaluation of a retrieved implant requires a review of the patient’s medical history and radiographs, and other studies (e.g., echocardiograms, MRI scans), where pertinent. Table III.1.5.3 provides a partial list of anatomic and physiologic conditions that may influence the failure or success of orthopedic and cardiovascular implants. The identification of acute and chronic problems presented by the patient often will provide guidance on how the evaluation of a specific implant should be carried out. For example, a clinical diagnosis of infection necessitates that biohazard precautions, sterile handling and microbiologic cultures should be used in the evaluation. In addition, gross examination and photography play an important role, and must be carried out before specific techniques are used to evaluate implants.

TABLE III.1.5.3 Patient Conditions and Other Factors Influencing Implant Failure or Success

| Orthopedic | Cardiovascular |

| Polyarthritis syndromes | Atherosclerosis |

| Connective-tissue disorders | Diabetes |

| Osteoarthritis | Infection |

| Trauma | Hypertension |

| Infection | Ventricular hypertrophy |

| Metabolic disease | Arrhythmias |

| Endocrine disease | Coagulation abnormalities |

| Tumor | Cardiac function |

| Primary joint disease | Recipient activity level |

| Osteonecrosis | |

| Recipient activity level |

It is critical to use a strategy that will allow optimal information yield using appropriate analytical protocols and techniques to assess host and implant responses. This strategy is directed toward developing correlative and cause-and-effect relationships among material, design, mechanical, manufacturing, clinical, and biological variables (Chapter III.1.3). Finally, whenever possible, analytical protocols and techniques should produce quantitative information that can be analyzed statistically. These analyses may also include clinical information.

Procedures used to evaluate devices and prostheses after function in animals and humans are largely the same. However, subject to humane treatment considerations, enumerated in institutional and federal guidelines and legislation, animal studies permit more detailed monitoring of device function and enhanced observation of morphologic detail (including blood–tissue–biomaterials interactions), as well as frequent assay of laboratory parameters (such as indices of platelet function or coagulation), and allow in situ observation of fresh implants following elective sacrifice at desired intervals. In addition, specimens from experimental animals can often be obtained rapidly, thereby minimizing the autolytic changes that occur when tissues are removed from their blood supply. Furthermore, advantageous technical adjuncts may be available in animal but not human investigations, including in vivo studies, such as injection of radiolabeled ligands for imaging platelet deposition, fixation by pressure perfusion that maintains tissues and cells in their physiological configuration following removal, and injection of various substances that serve as informative markers during analysis (such as indicators of endothelial barrier integrity). Animal studies often facilitate observation of specific complications in an accelerated time frame, such as calcification of bioprosthetic valves, in which the equivalent of 5–10 years in humans is simulated in 4–6 months in sheep (Schoen and Levy, 2005). Moreover, in preclinical studies, experimental conditions can be held constant among groups of subjects, including nutrition, activity levels, and treatment conditions. Consequently, concurrent control implants, in which only a single critical parameter varies, are often available in animal but not human studies.

Most implant retrieval involves examination of failed implants that have been surgically removed from patients or have been encountered at autopsy. Nevertheless, critical information can accrue from examination of “successful” implants removed after either fulfilling their function (e.g., a bone fixation device) or death of the patient resulting from an unrelated cause (e.g., heart valve prosthesis in a patient who dies of cancer). However, such studies may present difficulties, including but not limited to, access to the anatomic site, timing of the explantation following excessive postmortem interval, and family permission (Jacobs et al., 1999).

Approach to Assessment of Host and Implant Responses

Evaluation of the implant without attention to the tissue will produce an incomplete evaluation, and no understanding of the host response. Table III.1.5.4 provides a partial list of techniques for evaluating implants and tissues. We anticipate that novel implants and materials may dictate further techniques to be used in evaluating host–biomaterials interactions, and new analytical techniques will likely be developed.

Adequate and appropriate implant retrieval and evaluation require the quantitative assessment of host and implant responses using analytical protocols and non-destructive and destructive testing procedures. Techniques utilized for implant and tissue evaluation should be both device-designed and material-specific, permitting the collection of quantitative data that, in turn, can provide correlations and cause-and-effect relationships between material, design, mechanical, manufacturing, clinical, and biological variables. The evaluation techniques appropriate for a particular sample may be mutually exclusive, and the choice of a subset of techniques for evaluation may be dictated by the key clinical questions, and the availability and condition of the retrieved implant and tissue specimens. While a multilevel strategy is necessary for implant evaluation, analytical protocols and techniques are only utilized following a thorough understanding of the patient’s medical history, laboratory results, and associated information, and known and potential failure modes and mechanisms are considered.

TABLE III.1.5.4 Techniques for Implant Evaluation

| Implant | Tissue |

| Atomic absorption spectrophotometry | Atomic absorption spectrophotometry |

| ATR-FTIR | Autoradiography |

| Burst strength | Biochemical analysis |

| Compliance studies | Cell culture |

| Contact angle measurements | Chemical analysis |

| Digestability | Enzyme histochemistry |

| EDAX | Gel electrophoresis |

| ESCA | Histology |

| Extractability | Immunocytochemistry |

| Fatigue studies | Immunofluorescence |

| Fracture analysis | Immunohistochemistry |

| FTIR | Immunoperoxidase |

| Gel permeation chromatography | In situ hybridization |

| Glass transition temperature | Microbiologic cultures |

| Hardness studies | Molecular analysis for cellular gene expression |

| Light microscopy | Radiography |

| Macrophotography | Morphometry |

| Melt temperature | Transmission electron microscopy |

| Metallographic examination | Scanning electron microscopy |

| Particulate analysis | Tissue culture |

| Polarized light microscopy | |

| Porosity analysis | |

| Radiography | |

| Scanning electron microscopy | |

| Shrink temperature | |

| SIMS | |

| Stereomicroscopy | |

| Stress analysis | |

| Tensile studies | |

| Transmission electron microscopy | |

| Topography analysis |

In general, analytical protocols and techniques for assessing host and implant responses can be divided into two categories: nondestructive and destructive testing procedures. Only after appropriate accessioning, cataloging, and identification, and a complete review of the patient’s medical history and radiography, can the analytical protocols and techniques for implant evaluation be specified.

It should be noted that the techniques for implant evaluation are most commonly destructive techniques, that is, the implant or portions of the implant and the surrounding tissues must be destroyed or altered to obtain the desired information on the properties of the implant or material. The availability of the implant and tissue specimens will dictate the choice of technique.

Detailed analysis of the implant–tissue interface often necessitates that both a piece of tissue and a piece of the implant which it contacts be sectioned and examined in continuity (i.e., as one unit). This may necessitate special procedures, especially for polymer and ceramic implants in hard tissue (see below), which generally precludes any other analysis of that specimen. Similarly, chemical analysis of a piece of tissue for metal ion concentration requires acid digestion, and thus precludes morphological analysis. Thus, consideration must be given to either selection of multiple specimens or division of a specimen before processing, in order to permit part to be used for morphological and part for chemical analyses. Each of these portions may need to be further subdivided to be processed according to the requirements of specific tests. Moreover, since many of the procedures include cutting or sectioning a portion of the retrieved device, one must consider the legal aspects of device ownership, and destruction of what may become evidence in a court of law. Strict institutional guidelines need to be adhered to, and permission for use of destructive methods may be necessary. For clinicopathologic correlation studies that involve utilization of both patient data and pathological findings, approval of the local institutional review board (IRB) in the US is required. This is largely to ensure that the confidentiality and other interests of the patients from whom the implants were removed will be maintained, especially for purposes of publication or other dissemination of information.

Technical Problems of Metallic Implants, Bone, and Calcified Tissue

Evaluation of an implant and the surrounding host tissue when the implant was placed into bone, bone has formed around it, local tissue has calcified, or teeth presently pose unique problems. Dental implants and orthopedic implants are usually associated with hard tissue, but other implants may have contact with calcified tissue. Material containing calcified tissue, bone or teeth should be identified before the laboratory begins processing it or there may be harm to some of the equipment used for sectioning soft tissue. In addition some consensus standards, such as ASTM F561 and ISO/FDIA 12891-1, have been developed that address these special issues. Bone is a dynamic tissue, and analysis of bone formation and bone resorption may be a critical part of the study. Selection of techniques for evaluation must be undertaken carefully. Consideration needs to be given to what questions are being addressed before anything is cut or any harsh solutions are used.

If the implant and tissue are handled correctly, the techniques listed in Table III.1.5.4 are applicable to the study of hard tissue and associated implants. As stated earlier, some techniques are mutually exclusive. For example, histologic analysis of particle size and quantity, and chemical digestion and analysis for metal ions cannot be done on the same sample. Following routine fixation to preserve cellular detail, either of two generic approaches may be taken with implants adjacent to hard tissue: preparation of undecalcified sections or decalcification prior to embedding. Fully decalcified bone can be embedded and sectioned using methods common to soft-tissue pathology. To prepare undecalcified sections, hard tissue and the associated implant component or section are dehydrated and embedded in a hard plastic (usually methyl methacrylate) and thick (approximately 500 μm) sections are cut with a diamond saw and ground down to form the final thin section (approximately 50 μm). The advantage of undecalcified sections is that areas of mineralization and newly formed bone can be clearly distinguished from soft tissue. Specimen X-rays can also be taken to identify sites and extent of mineralization. Assistance with techniques for evaluation of specimens containing bone is available from the Society of Histotechnology and elsewhere (McNeil et al., 1997; Sanderson and Bachus, 1997; Callis and Strerchi, 1998).

Other special techniques may need to be developed and/or adapted to study particular issues. For example, stents composed of metallic wires are now commonly used in many clinical applications, including peripheral vascular disease intervention, biliary obstruction, endovascular repair of aneurysms, and percutaneous coronary interventions. In the examination of vascular stents, it is particularly important to determine if the stent is open or has become obstructed, and identify specific biomaterial–tissue interactions, without disturbing the key interfaces during dissection. A rapid and cost-effective method was recently described to dissolve most metallic stents, leaving the vascular and luminal tissues intact, in order to facilitate this type of analysis (Bradshaw et al., 2009).

Other Special Issues

Because implant retrieval programs may obtain data that will be used in regulatory or litigation procedures, it is important to document the disposition and appearance of the tissue, and of the implant, at each stage in the evaluation. Ample use of photography will greatly help in the description of the tissue and implant condition at each step of analysis. Careful labeling that is recorded during photography is helpful in later reviews of the evaluation procedure.

Concerns relative to the safety of laboratory personnel arise in the examination of retrieved materials and tissues, especially with respect to infection. If the device and/or tissues arrive in the laboratory without having been adequately disinfected or treated, special precautions need to be observed with the use of barrier clothing and gloves, and the use of biosafety cabinets. All safety regulations of the institution need to be known and followed. Procedures for disposal of hazardous chemicals also need to be carefully observed. If untreated devices or tissues are to be packaged and shipped from the clinical setting to the laboratory, care must be taken to follow the rules and regulations of the shipping agency and the Department of Transportation for transportation of biohazardous material. ASTM Committee F04 has a draft standard WK13292, Standard Guide for Shipping Possibly Infectious Materials, Tissues, and Fluids. This document contains guidelines and references for all the regulatory issues involved in shipping explant related materials.

An additional and very complex matter relates to implant ownership (Beyleveld et al., 1995). Several parties may have (and claim) rights to possession of a removed device under various circumstances: the patient, the surgeon, the pathologist, the hospital, an entity such as an insurance company, and attorneys representing both the plaintiff and the defendant in product liability or malpractice litigation. Moreover, ownership may not automatically entail the right to test. These issues are both controversial and unresolved.

The Multilevel Strategy to Implant Evaluation

Implant retrieval and analysis protocols often utilize a multilevel approach along the spectrum of essential documentation to the use of sophisticated research tools. Some investigators have advocated a basic two-level approach (Table III.1.5.5). Level I studies include routine evaluation modalities capable of being done in virtually any laboratory, and that characterize the overall safety and efficacy of a device. Level II studies comprise well-defined and meaningful test methods that are difficult, time-consuming or expensive to perform, require special expertise or yield more investigative or esoteric data. Since some level II analyses may be mutually exclusive, some material might routinely need to be accessioned, set aside (during level I analyses), and prepared for more specialized level II studies, in the event that they should be indicated later. Level II evaluation is usually undertaken with specific investigative objectives directed toward a focused research question or project. Prioritized, practical approaches using these guidelines have been described for heart valves, cardiac assist devices and artificial hearts, and other cardiovascular devices (Schoen et al., 1990; Borovetz et al., 1995; Schoen, 1995, 2001; Schwartz and Edelman, 2002, 2004).

TABLE III.1.5.5 Study Prioritization

Level I Studies

Gross dissection

Photographic documentation

Microbiologic cultures

Radiography

Light microscopic histopathology

Level II Studies

Scanning electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy

Energy dispersive X-ray microanalysis (EDXA)

Analysis of adsorbed and absorbed proteins

Mechanical properties measurement

Materials surface analysis

Leukocyte immunophenotypic studies

Molecular analyses for cellular gene expression or extracellular matrix production

Both ASTM and ISO implant retrieval standards (F561 and ISO 12891, respectively) have utilized a three-stage approach to implant analysis. Stage I analysis consists of routine device identification and description. Stage II is more detailed, time-consuming, and expensive, and includes photography and non-destructive failure analysis. Since stage I and II protocols are the same for all material types, they are combined in F561. Stage III protocols include destructive analytical techniques, many of which are specific to particular material types, and thus separate guidelines are provided for metallic, polymeric, and ceramic materials. Combinations of these protocols provide guidelines for analysis of the various components of composites and tissue engineered materials.

The Role of Implant Retrieval in Device Development

For implants placed into many anatomic sites, prosthesis-associated pathology is a major determinant of quality of life and prognosis of patients. Implant retrieval and evaluation plays a critical role in the evolution of medical devices through development and clinical use (Figure III.1.5.1). Implants are examined as: (1) fabricated but unimplanted prototypes, to reveal changes in device components induced by the fabrication process that can predict (or lead to an understanding of) failure modes observed subsequently; (2) specimens that have been subjected to in vitro tests of biocompatibility or durability; (3) specimens removed from animal models following in vivo function, usually as actual devices; (4) specimens that accrue in carefully controlled clinical trials; and (5) failed or functioning specimens that are explanted in the course of ongoing surveillance of general clinical use of a device following regulatory approval. In each case, implant retrieval is concerned with the documentation of device safety and efficacy, and problems that dictate modification of design, materials or use of the implants in patients (e.g., patient–device matching or patient management). Devices are explanted and analyzed with attention directed toward all complications, but especially those that may be considered special vulnerabilities engendered by the device type. Efforts are made to retrieve and evaluate as many such implants as possible, both failed and nonfailed. Evaluation of retrieved animal implants plays a special role in the documentation for the FDA-Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) required for a clinical trial and for the FDA-Premarket Approval (PMA) required for general marketing. The literature contains numerous instances where problem-oriented implant evaluation studies have yielded important insights into the deficiencies and complications that have limited the success of various implants. Implant retrieval has also contributed to the assessment of the safety and efficacy of implant modifications intended to be improvements. The conceptual approach to the analysis of a failed implant is explored in Chapter III.1.3.

Common failure modes of cardiovascular implants include thrombosis, embolism, calcification, and infection, whereas those of orthopedic and dental implants are loosening, wear, and infection. Implant retrieval studies have, and will continue to have, significant clinical, as well as research and development, utility. Specific implant designs can lead to specific types of complications and failure. Implant retrieval and evaluation with the identification of failure modes and mechanisms have played a significant role in the evolution of medical devices and will continue to be crucial for the evaluation of “next” generation devices.

What Clinically Useful Information has been Learned from Implant Retrieval and Analysis?

Cardiovascular Implants

Cardiovascular implants commonly involve both blood and soft-tissue interactions with materials. The complications most commonly found with these implants, i.e., heart valve prostheses, vascular grafts, cardiac assist devices/artificial hearts, and vascular stents are listed in Tables III.1.5.6 and III.1.5.7. Perspectives, approaches, and techniques for evaluating cardiovascular implants have been described (Schoen et al., 1990; Borovetz et al., 1995; Schoen, 1995, 2001; Schwartz and Edelman, 2002, 2004). Specific examples from the field of cardiovascular prostheses are summarized next and in Table III.1.5.8, to illustrate the scope and utility of this activity.

TABLE III.1.5.6 Complications of Heart Valve Substitutes, Vascular Grafts, and Cardiac Assist/Replacement Devices

| Heart Valve Prostheses | Vascular Grafts | Cardiac Assist/Replacement Devices |

| Thrombosis | Thrombosis | Thrombosis |

| Embolism | Embolism | Embolism |

| Paravalvular leak | Infection | Endocarditis |

| Anticoagulation-related hemorrhage | Perigraft erosion | Extraluminal infection |

| Infective endocarditis | Perigraft seroma | Component fracture |

| Extrinsic dysfunction | False aneurysm | Hemolysis |

| Incomplete valve closure | Anastomotic hyperplasia | Calcification |

| Cloth wear | Disintegration/degradation | |

| Hemolytic anemia | ||

| Component fracture | ||

| Tissue valves | ||

| Cusp tearing | ||

| Cusp calcification |

TABLE III.1.5.7 Complications of Vascular Stents

Thrombosis

Proliferative restenosis

Strut-related inflammation

Foreign-body reaction

Incomplete expansion

Overexpansion

Infection

Malposition

TABLE III.1.5.8 Clinical Utility of Retrieval Studies: Heart Valve Substitutes

Experience with caged-ball mechanical prosthetic heart valves in the 1960s demonstrated both thrombus and degradation as complications. Degradation of silicone due to lipid absorption (called ball variance) was virtually eliminated by improved curing of silicone poppets (Hylen et al., 1972). Subsequently, a cloth-covered caged-ball mechanical prosthetic heart valve that had a ball fabricated from silicone and a metallic cage covered by polypropylene mesh was introduced. The cloth-covered cage struts were designed to encourage tissue ingrowth, and thereby decrease thromboembolism. Preclinical studies in pigs, sheep, and calves demonstrated rapid healing by fibrous tissue of the cloth-covered struts. However, subsequent clinical studies of these valves showed abundant cloth wear in some patients, sufficient to cause escape of the ball through the spaces between the cage struts, a circumstance that was usually fatal without emergency surgery (Schoen et al., 1984). This analysis demonstrated the general concept that valve prostheses used in humans may have important complications that were not predicted by animal investigations, in this case because the vigorous healing that occurred in animals, but not in humans, obscured the potential problem.

Modification of a tilting-disk valve design intended to permit enhanced opening and thereby reduce thromboembolism also led to a new complication – strut fracture with escape of the disk. Careful studies of retrieved valves made a critical contribution to understanding and managing this serious clinical problem (see Prosthetic Heart Valve Case Study). Multiple coordinated studies of retrieved experimental and clinical implants have characterized and facilitated therapeutic approaches toward elimination of calcification-induced failure modes in bioprosthetic tissue heart-valve replacement (Schoen and Levy, 1999, 2005).

Such studies have identified the causes and morphology of failure, patterns of mineral deposition, nature of the mineral phase, and early events in the mechanisms of calcification. Calcification of valve tissue in both circulatory and subcutaneous animal models exhibits morphological features similar to that observed in clinical specimens, but calcification is markedly accelerated in the experimental explants. Such studies have provided the means to test approaches to inhibit bioprosthetic valve calcification by modifying host, implant, and mechanical influences. These studies serve to emphasize that biological, as well as mechanical, failure mechanisms can be understood using specifically chosen and controlled animal model investigations, guided by and correlated with the results of careful studies of retrieved clinical specimens. Furthermore, they show how implant retrieval studies can be used as a critical component of a program to ensure efficacy and safety of potential therapeutic modifications.

An additional use of retrieval studies is exemplified by a case in which a change in biomaterials was shown

Case Study Prosthetic Heart Valve Case Study

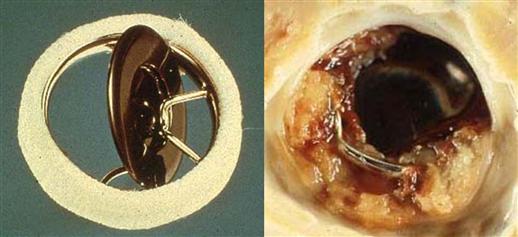

Often cited as the prototypical device failure analysis that contributed important clinical information, the problem of the Björk-Shiley tilting disk mechanical valve prosthesis provides an instructive case history. The prosthesis of original design, initially in which a Delrin® polymer disk and later a pyrolytic carbon disk was held in place by a wire superstructure composed of inflow and outflow struts, was associated with an unacceptable late failure rate owing to thrombotic occlusion (Figure III.1.5.2). The inflow strut was an integral part of the valve base while the outflow strut was welded to the base ring.

FIGURE III.1.5.2 Björk-Shiley mechanical heart valve prosthesis. Left: Original model with pyrolytic carbon disk, unimplanted. Right: thrombosed prosthesis. (B) from Schoen F.J., Levy, R.J., Piehler, H.R. (1992). Pathological Considerations in replacement heart valves. Cardiovascular Pathology 1:29–52.

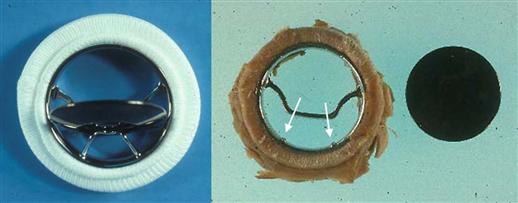

In order to reduce the risk of thrombosis by improving valve flow, the company manufacturing the valve (Shiley, Inc.) redesigned the prosthesis to achieve opening angles of the disk of 60° or 70° from the plane of the valve base and rounded the surfaces of the disk (“convexo-concave” or “C-C”). However, clinical use of the redesigned Björk-Shiley C-C heart valve led to an unusually large cluster of cases in which the metallic outlet strut fractured in two places, leading to disk escape (Figure III.1.5.3). The complication was fatal in the majority of patients in whom it occurred. In 2005, strut fracture was reported in at least 633 of the 86,000 valves of this type implanted worldwide during 1978–1986. Clinical studies identified large valve size, mitral site, young recipient age, and valve manufacture date as risk factors for this failure mode (Blot et al., 2005). The mechanisms of this problem were elucidated through careful analysis using retrieved implant analysis, coupled with other methods.

FIGURE III.1.5.3 Modified Björk-Shiley mechanical heart valve prosthesis with convexo-concave disk and 70° opening. Left: Unimplanted valve. Right: Explanted valve with outflow strut fracture at welds (arrows). Disk had escaped from housing and the outflow strut piece was not located. (B) from Schoen F.J., Levy, R.J., Piehler, H.R. (1992). Pathological considerations in replacement heart valves. Cardiovascular Pathology 1:29–52.

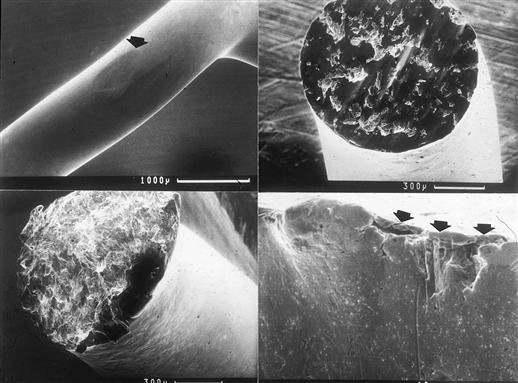

Pathologic studies of retrieved Björk-Shiley valves, enhanced by scanning electron microscopy, demonstrated a pronounced wear facet at the tip of the outlet struts, and localized pyrolytic carbon wear deposits at sites where the closing disk contacted the strut (Schoen et al., 1992), providing a fatigue fracture mechanism that began on the inflow side of the outlet strut often initiated within a weld joint (Figure III.1.5.4). The analysis suggested that the first strut leg fracture typically initiated at or near the point of maximum bending stress, was traced to a site of weld shrinkage porosity and/or inclusion in most cases, and was followed by fracture of the second leg. Occasionally, valves with only a single strut fracture were encountered. This showed that the underlying problem in catastrophic failure was metal fatigue failure, probably initiated by over-rotation of the disk during valve closure in this design, leading to excessive bending stresses at or near the welds joining the outlet struts to the housing, and potentially coupled with intrinsic weld flaws.

FIGURE III.1.5.4 Analysis of retrieved Björk-Shiley convexo-concave mechanical heart valve prosthesis. Upper left: Elliptical wear flat on tip of outlet strut resulting from contact with disk during closure. Upper right: Worn and abraded surface of first strut leg to fracture. Origin of the fatigue fracture is at bottom center. Lower left: Fracture surface of second leg to fracture; stigmata of fatigue fracture are absent. Lower right: Residual weld fracture at the base of valve showing weld porosity and secondary cracking (arrows). From Schoen F.J., Levy, R.J., Piehler, H.R. (1992). Pathological Considerations in replacement heart valves. Cardiovascular Pathology 1:29–52.

Moreover, in subsequent animal studies in which Björk-Shiley 60–70° C-C valves were implanted in sheep and instrumented with strain gauges showed that impact forces varied greatly with cardiac activity, and that loads occurring during exercise were significantly elevated. This correlated with clinical data that showed that fracture often occurred during exertion.

The Björk-Shiley heart valve case demonstrates that elucidation of a failure mode by detailed materials failure analysis can have potential impact on patient management. Understanding this mode of failure has enabled development of non-invasive testing modalities (via high-definition radiography (O’Neill et al., 1995) or acoustic characterization of strut status (Plemons and Hovenga, 1995)) to establish when one strut has fractured prior to the onset of clinical failure, to caution patients with these valves against vigorous exercise, and to consider re-replacement of properly functioning valves at high risk of fracture. Moreover, this case has reinforced certain principles of valve testing which should occur before widespread clinical use of a new or modified prosthesis design (Blackstone, 2005).

to be beneficial. Implant retrieval studies of a low-profile disk valve composed of a disk and cage fabricated from Teflon® demonstrated poor wear properties of the disk. After a new model of the valve with disk and struts fabricated from pyrolytic carbon was introduced, clinical experience suggested that the use of carbon contributed to a major advancement in the durability of prosthetic heart valves. Retrieval studies of carbon valves recovered at autopsy or surgery, and analyzed by surface scanning electron microscopy and surface profilometry indicated that, compared with valves composed of Teflon®, carbon valves exhibited minimal abrasive wear (Schoen et al., 1982). This study revealed that although analysis of implants and medical devices has traditionally concentrated on those devices that failed in service, important data can accrue from implants serving the patient until death or removal for unrelated causes. Thus, detailed examination of the properly functioning prostheses removed from patients after a long duration of implantation may yield worthwhile data, provided that a focused question is asked of the material.

Other retrieval studies have revealed: (1) the cause of excessive thrombosis of a new bileaflet tilting-disk design (Gross et al., 1996); (2) the cause of mechanical failure of a new pericardial bioprosthesis fabricated from photofixed bovine pericardium that had different mechanical properties than conventional glutaraldehyde-fixed tissue (Schoen, 1998a); and (3) the cause of failure and characteristic changes that occur in cryopreserved allograft aortic heart valves transplanted from one individual to another (Mitchell et al., 1998). Studies of ventricular assist devices have demonstrated the importance of valves or biomaterial junctions in initiating thrombosis (Fyfe and Schoen, 1993; Wagner et al., 1993), and several studies have described the failure modes of specific types of vascular grafts in different locations (Canizales et al., 1982; Downs et al., 1991; Guidoin et al., 1993), and the morphology of vascular stents (Anderson et al., 1992; van Beusekom et al., 1993; Farb et al., 2002).

Oxidative biodegradation and environmental stress cracking of polyether polyurethane pacemaker lead insulation have been identified as failure mechanisms of pacemaker leads (Wiggins et al., 2001). Reactive oxygen radicals, released by adherent macrophages and foreign-body giant cells in the foreign-body reaction oxidize the polyether component of the polyurethane, leading to oxidative chain cleavage of the polymer and subsequent failure. These findings have lead to the development of new polyurethanes that are oxidation-resistant or inhibit the adhesion and activation of adherent cells in the foreign-body reaction at the tissue–material interface (Anderson et al., 2007).

Orthopedic and Dental Implants

Complications most commonly found with orthopedic and dental implants are presented in Table III.1.5.9 and Table III.1.5.10, respectively. The clinical utility of hard-tissue (orthopedic and dental) implant retrieval and evaluation is summarized in Table III.1.5.11.

TABLE III.1.5.9 Complications of Orthopedic Implants

| Bone resorption | Loosening |

| Corrosion | Mechanical mismatch |

| Fatigue | Fracture |

| Fibrosis | Motion and pain |

| Fixation failure | Particulate formation |

| Fracture | Surface wear |

| Incomplete osseous integration | Stress riser |

| Infection | |

| Interface separation |

TABLE III.1.5.10 Complications of Dental Implants

| Adverse foreign-body reaction | Loosening |

| Biocorrosion | Foreign-body reaction |

| Electrochemical galvanic coupling | Corrosion |

| Fatigue | Particulate formation |

| Fixation failure | Wear |

| Fracture | |

| Infection | |

| Interface separation | |

| Loss of mechanical force transfer |

TABLE III.1.5.11 Clinical Utility of Retrieval Studies: Hard-Tissue Implants

Early studies were concerned primarily with metallic devices used for internal fixation of fractures. Examination of some early designs showed failure at regions of poor metallurgy or weak areas due to poor design (Cahoon and Paxton, 1968). Other studies (Wright et al., 1982; Cook et al., 1985) reinforce the importance of material and design, such as the pitfall of stamping the manufacturer’s name in the middle of the plate where stresses are high. Modern total hip replacements have also had fatigue fractures initiated at labels etched at high-stress regions (Woolson et al., 1997). Galvanic corrosion due to mixed metal alloys was also demonstrated in early retrieval studies (Scales et al., 1959). Analyses of fixation devices have shown a correlation between corrosion and biological reactions, such as allergic reactions to metallic elements in the implants (Brown and Merritt, 1981; Cook et al., 1988; Merritt and Rodrigo, 1996).

The development of the low-friction total hip arthroplasty by Charnley is a classical example of how implant retrieval can yield important clinical information which impacts implant materials and design (Charnley et al., 1969). The initial choice for the low-friction polymeric cup (replacing the acetabulum) was a Teflon®-like PTFE. As described above for heart valves, this relatively soft material had a very high wear rate, and within a few years many hip replacements had been removed due to severe wear and intense inflammatory reactions. The analysis of the retrievals has also demonstrated the relationships between large head diameter, and the wear debris and excessive wear that have served as the basis for our understanding of joint bearing design. Clinical and retrieval studies are now examining the performance of metal-on-metal total hip bearing couples (Kwon et al., 2010; Ebramzadeh et al., 2011).

Teflon® was replaced by ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) as the acetabular cup bearing surfaces, and retrieval studies have continuously stimulated changes in the methods of processing UHMWPE. Retrieval studies have demonstrated that reinforcing UHMWPE with carbon fibers did not sufficiently improve its strength (Wright et al., 1988). Heat pressing to improve surface hardness was not effective with some total knee designs (Bloebaum et al., 1991; Wright et al., 1992).

The physical and mechanical properties of UHMWPE are altered by ionizing radiation, due to the generation of free radicals. Oxidative degradation of UHMWPE components radiation sterilized in air-permeable packaging occurs during sterilization, during shelf-storage prior to implantation, and in vivo. Oxidation has a detrimental effect on UHMWPE, leading to a decrease in the elongation to failure, an increase in elastic modulus, and a decrease in fatigue crack propagation resistance (Kurtz, 2009), and has resulted in the premature failure of some UHMWPE components in vivo. Contemporary radiation sterilization practices (e.g., sterilization in an inert gas or vacuum) for UHMWPE have largely eliminated the potential for shelf aging; however, in vivo oxidation occurs and remains a concern (Kurtz et al., 2006).

Case Study Orthopedic Hip Prosthesis Case Study

One of the most dramatic examples of effective implant retrieval and analysis is that of the zirconia femoral ball head made under the trade name of Prozyr® by Saint-Gobain Ceramiques Desmarquest. By mid-1998 they had made thousands of these with very low failure rates. However, in 1998 they changed a processing step from batch furnace sintering to a continuous flow “tunnel furnace” (Clarke et al., 2003). In 2001 reports of catastrophic head fracture were being reported by the primarily European manufacturers. On August 10, 2001, the French Agency of Health Security of Health Products issued a recall on all TH batches from the tunnel furnace. On August 16, 2001, the British Therapeutic Goods Administration issued a similar recall. The major manufacturers involved were European and Australian divisions of Biomet, DePuy, Smith & Nephew, Zimmer, and Stryker Howmedica Osteonics.

What followed was an intense international study of device failure. The company organized a committee of experts. They met with the national regulatory authorities to discuss the issue. Failed and non-implanted devices were studied. As of April 2003 (http://www.prozyr.com/PAGES_UK/Biomedical/breakages.htm), Saint-Gobain was reporting on their web site that six TH batches had fracture problems; the two major failure batches had failure rates of 33% (227 out of 683) and 8.7% (60 out of 692).

So what was learned? Zirconia is a metastable ceramic which will undergo a phase transformation at room temperature (Chevalier et al., 2004) which is partially stabilized by the addition of Yttria. With proper sintering, the material obtains maximum density, and the result is a very strong material (Clarke et al., 2003; Chevalier et al., 2004) which was thus considered a better ceramic than its more brittle alternative, alumina. However, some of the batch furnace runs produced balls which were not fully densified in the center of the ball. This unstable material was exposed by boring out the center for taper fit to the metallic femoral stems. Very careful analysis of failures, non-implanted balls, and the “carrots” produced by the hollow core drills used to drill out the balls revealed that this material was subject to environmental degradation, phase transformation, and fracture (Clarke et al., 2003; Chevalier, 2006). While subsequent batches had better thermal controls and the carrots were fully dense, the global impact of such a large failure rate and recall resulted in the company’s decision to pull Prozyr® off the market (Chevalier, 2006). Subsequent analysis of other Y-TZP products may well restore clinical confidence in this material.

Highly cross-linked UHMWPE formulations have been in clinical use for a decade as a means to improve wear resistance of acetabular hip components. Clinical studies of highly cross-linked acetabular hip components support reduced wear within the first decade of use (Muratoglu et al., 2004; Bragdon et al., 2007). However, cross-linking adversely affects uniaxial ductility, fracture toughness, and fatigue crack propagation resistance (Rimnac and Pruitt, 2008; Sobieraj and Rimnac, 2009). Due to the changes in mechanical properties of first-generation highly cross-linked UHMWPE materials, there has been concern regarding the potential propensity of in vivo fracture of highly cross-linked UHMWPE joint replacement components. In fact, in vivo fractures of highly cross-linked UHMWPE hip components have been reported, though the numbers are small (Tower et al., 2007; Furmanski et al., 2008). Also, when UHMWPE is cross-linked via ionizing radiation, free radicals are generated that can lead to oxidative degradation; thus, post-processing above (remelting) or below (annealing) the melt temperature is usually conducted. Remelting effectively eliminates free radicals, but also alters crystallinity, which affects mechanical properties. Annealing preserves the original crystal structure better, but is not as effective at reducing free radicals as remelting so that oxidation is possible with annealed cross-linked UHMWPE formulations (Rimnac and Pruitt, 2008). More recently, sequential radiation/annealing and incorporation of vitamin E (as a free-radical scavenger) have been introduced (the second-generation highly cross-linked UHMWPE materials) as methods by which to more effectively reduce or eliminate free radicals while preserving crystallinity (Oral et al., 2006; Sobieraj et al., 2008).

Implant retrieval and analysis has provided critical information toward understanding the anchoring of implants in bone. Branemark and associates demonstrated that direct bone–metal osseointegration of titanium tooth-root implants was possible with carefully controlled surgical technique and implant surface preparation (Albrektsson et al., 1982). Porous coatings may be applied to implants to facilitate bony ingrowth; relationships between pore size and bony ingrowth have come from retrieval studies (Cook et al., 1988).

Examination of the interface between the bone and the acrylic bone cement in long-term implant recipients examined at autopsy demonstrated the presence of inflammation with macrophages, thus providing the initial description of bone resorption due to particulate debris (Charnley, 1970). The relationship between the amount of particulate wear debris generated and bone resorption due to inflammation, i.e., osteolysis, was graphically demonstrated by the retrieval and tissue studies of Willert and Semlitsch (1977). Extensive research has been conducted over the years looking at osteolysis or “particle disease,” and characterization of the polymeric debris, as correlated with implant type and design (Schmalzied et al., 1997). Studies on tissue reactions to particulates and wear debris require special histologic evaluation, as described by Wright and Goodman (1996), in the various consensus standards, in other references cited earlier, and in many other studies readily available in the orthopedic or histotechnology literature (see Goodman and Wright, 2007; Burke and Goodman, 2008; Purdue, 2008; Revell, 2008a,b).

Implant retrieval studies have demonstrated that the success of a material in one application may not necessarily translate to another. For example, titanium does well as a bone–implant interface, but it may be subject to severe wear as a bearing surface (Agins et al., 1988). An alternative approach in the hip was to use titanium alloy stems with modular press-fit heads made of a more wear-resistant cobalt alloy. However, some of these designs demonstrated significant corrosion, which was first attributed to use of mixed metals (Collier et al., 1991), and later to microgalvanic corrosion of the cast heads (Mathiesen et al., 1991), and to micromotion and fretting corrosion between components (Brown et al., 1995).

As with orthopedic devices, complications of dental implants may be related to the mechanical–biomechanical aspects of force transfer, or the chemical–biochemical aspects of elements transferred across biomaterial and tissue interfaces, or both. The complex synergism that exists between tissue and biomaterial responses presents a significant challenge in the identification of the failure mechanisms of dental implants. Since many dental devices are percutaneous, in that they contact bone but are also exposed to the oral cavity, the problems of infection are also significant (Moore, 1987; Sussman and Moss, 1993). Lemons (1988) and others have provided appropriate perspectives to be taken in the evaluation of dental implants.

Conclusions

Although the focus of this chapter has been on the retrieval and evaluation of implants in humans, the perspectives, approaches, techniques, and methods may also apply to the evaluation of new biomaterials, preclinical testing for biocompatibility, and premarket clinical evaluation. Each type of in vivo or clinical setting has its unique implant–host interactions, and therefore requires the development of a unique strategy for retrieval and evaluation.

Indeed, for investigation of bioactive materials and tissue engineered medical devices, in which interactions between the implant and the surrounding tissue are complex, novel and innovative approaches must be used in the investigation of in vivo tissue compatibility. In such cases, the scope of the concept of “biocompatibility” is much broader, and the approaches of implant retrieval and evaluation require measures of the phenotypes and functions of cells, and the architecture and remodeling of extracellular matrix and the vasculature (Mizuno et al., 2002; Peters et al., 2002; Rabkin et al., 2002; Rabkin and Schoen, 2002). Moreover, a critical role of implant retrieval will be the identification of tissue characteristics (biomarkers) that will be predictive of (i.e., surrogates for) success and failure. A most exciting possibility is that such biomarkers may be used to noninvasively image/monitor the maturation/remodeling of tissue engineered devices in vivo in individual patients (Mendelson and Schoen, 2006).

Bibliography

1. Agins HJ, Alcock NW, Bansal M, Salvati EA, Wilson PD, et al. Metallic wear in failed titanium-alloy hip replacements. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A:347–356.

2. Albrektsson T, Branemark P-I, Hansson H-A, Lindstrom J. Osseo-integrated titanium implants. Acta Orthop Scand. 1982;52:155–170.

3. Anderson JM. Procedures in the retrieval and evaluation of vascular grafts. In: Kambic HE, Kantrowitz A, P. Sung P, eds. Vascular Graft Update: Safety and Performance. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM STP 898 American Society for Testing and Materials; 1986:156–165.

4. Anderson JM. Cardiovascular device retrieval and evaluation. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1993;2(Suppl. 3):199S–208S.

5. Anderson JM, Christenson EM, Hiltner A. Biodegradation mechanisms of polyurethane elastomers. Corros Eng Sci Techn. 2007;42(4):312–323.

6. Anderson PG, Bajaj RK, Baxley WA, Roubin GS. Vascular pathology of balloon-expandable flexible coil stent in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:372–381.

7. ASTM F561–05a. Practice for retrieval and analysis of implanted medical devices, and associated tissues and fluids. ASTM Annual Book of Standards. 2005;Vol. 13.01:2008.

8. Beyleveld D, Howells GG, Longley D. Heart valve ownership: Legal, ethical and policy issues. J Heart Valve Dis. 1995;4:S2–S5.

9. Blackstone EH. Could it happen again? The Björk-Shiley convexo-concave heart valve story. Circulation. 2005;111:2850–2857.

10. Bloebaum RD, Nelson K, Dorr LD, Hoffman A, Lyman DJ. Investigation of early surface delamination observed in retrieved hard-pressed tibial inserts. Clin Orthop. 1991;269:120–127.

11. Blot WJ, Ibrahim MA, Ivey TD, Acheson DE, Brookmeyer R, et al. Twenty-five-year experience with Björk-Shiley convexoconcave heart valve: A continuing clinical concern. Circulation. 2005;111:2850–2857.

12. Borovetz HS, Ramasamy N, Zerbe TR, Portner PM. Evaluation of an implantable ventricular assist system for humans with chronic refractory heart failure Device explant protocol. ASAIO J. 1995;41:42–48.

13. Bradshaw SH, Kennedy L, Dexter DF, Veinot JP. A practical method to rapidly dissolve metallic stents. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2009;18:127–133.

14. Bragdon CR, Kwon YM, Geller JA, Greene ME, Freiberg AA, et al. Minimal 6-year followup of highly cross-linked polyethylene in THA. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2007;465:122–127.

15. Brown SA, Merritt K. Metal allergy and metallurgy. In: Weinstein A, Gibbons D, Brown S, Ruff W, eds. Implant Retrieval: Material and Biological Analysis, NBS SP 601. Washington, DC: National Bureau of Standards Special Pubication; 1981;299–321.

16. Brown SA, Flemming CAC, Kawalec JS, Placko HE, Vassaux C, et al. Fretting accelerated crevice corrosion of modular hip tapers. J Appl Biomater. 1995;6:19–26.

17. Burke M, Goodman S. Failure mechanisms in joint replacement. In: Revell P, ed. Joint Replacement Technology. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead; 2008;264–285.

18. Cahoon JR, Paxton HW. Metallurgical analysis of failed orthopaedic implants. J Biomed Mater Res. 1968;2:1–22.

19. Callis G, Strerchi D. Decalcification of bone: Literature review and practical study of various decalcifying agents Methods, and their effects on bone histology. J Histotechnol. 1998;21:49–58.

20. Canizales S, Charara J, Gill F, Guidoin R, Roy PE, et al. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene prostheses as secondary blood access sites for hemodialysis: Pathological findings in 29 excised grafts. Can J Surg. 1982;154:17–26.

21. Charnley J. The reaction of bone to self-curing acrylic cement A long-term histological study in man. J Bone Joint Surg. 1970;53B:340–353.

22. Charnley J, Kamangar A, Longfield MD. The optimum size of prosthetic heads in relation to the wear of plastic sockets in total replacement of the hip. Med Biol Eng. 1969;7:31–39.

23. Chevalier J. What future for zirconia as a biomaterial?. Biomaterials. 2006;27:535–543.

24. Chevalier J, Deville S, Munch E, Julian R, Lair F. Critical effect of cubic phase on aging of 3 mol% yttria-stabilized zirconia ceramics for hip replacement prostheses. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5539–5545.

25. Clarke IC, Manaka M, Green DD, Williams P, Pezzotti G, et al. Current status of zirconia used in total hip implants. J Bone Joint Surg AM. 2003;85A:73–84.

26. Collier JP, Suprenant VA, Jensen RE, Mayor MB. Corrosion at the interface of cobalt-alloy heads on titanium alloy stems. Clin Orthop. 1991;271:305–312.

27. Cook SD, Renz EA, Barrack RL, Thomas KA, Harding AF, et al. Clinical and metallurgical analysis of retrieved internal fixation devices. Clin Orthop. 1985;184:236–247.

28. Cook SD, Barrack RL, Thomas KA, Haddad Jr RJ. Quantitative analysis of tissue growth into human porous total hip components. J Arthroplasty. 1988a;3:249–262.

29. Cook SD, Thomas KA, Haddad Jr RJ. Histologic analysis of retrieved human porous-coated total joint components. Clin Orthop. 1988b;234:90–101.

30. Downs AR, Guzman R, Formichi M, Courbier R, Jausseran JM, et al. Etiology of prosthetic anastomotic false aneurysms: Pathologic and structural evaluation in 26 cases. Can J Surg. 1991;34:53–58.

31. Ebramzadeh E, Campbell PA, Takamura KM, Lu Z, Sangiorgio SN, et al. Failure modes of 433 metal-on metal hip implants: How, why, and wear. Orthop Clin N Am. 2011;42:241–250.

32. Farb A, Sangiorgi G, Carter AJ, Walley VM, Edwards WD, et al. Pathology of acute and chronic coronary stenting in humans. Circulation. 2002;105:2932–2933.

33. Furmanski, J., Atwood, S., Bal, B. Anderson, M. R. & Penenberg, B. L. et al. (2008). Fracture of highly cross-linked UHMWPE acetabular liners. Proceedings of the 7th Annual AAOS, SE18.

34. Fyfe B, Schoen FJ. Pathologic analysis of 34 explanted Symbion ventricular assist devices and 10 explanted Jarvik-7 total artificial hearts. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1993;2:187–197.

35. Goodman SB, Wright TM. AAOS/NIH workshop – Osteolysis and implant wear: Biological, biomedical engineering and surgical principles. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;16.

36. Gross JM, Shu MCS, Dai FF, Ellis J, Yoganathan AP. A microstructural flow analysis within a bileaflet mechanical heart valve hinge. J Heart Valve Dis. 1996;5:581–590.

37. Guidoin R, Chakfe N, Maurel S, How T, Batt M, et al. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene arterial prostheses in humans: Histopathological study of 298 surgically excised grafts. Biomaterials. 1993;14:678–693.

38. http://www.prozyr.com/PAGES_UK/Biomedical/breakages.htm Accessed 7.04.03.

39. Hylen JC, Hodam RP, Kloste FE. Changes in the durability of silicone rubber in ball-valve prostheses. Ann Thorac Surg. 1972;13:324.

40. ISO Soliclus/FDIA 12891-1. Retrieval and Analysis of Implantable Medical Devices.

41. Jacobs JJ, Patterson LM, Skipor AK, Urban RM, Black J, et al. Postmortem retrieval of total joint replacement components. J Biomed Mater Res (Appl Biomater). 1999;48:385–391.

42. Kurtz SM. The UHMWPE Handbook: Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene in Total Joint Replacement. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Academic Press; 2009.

43. Kurtz SM, Hozack WJ, Purtill JJ, Marcolongo M, Kraay MJ, et al. Significance of in vivo degradation for polyethylene in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2006;453:47–57.

44. Kwon Y-M, Glyn-Jones S, Simpson DJ, Kamali A, McLardy-Smith P, et al. Analysis of wear of retrieved metal-on metal hip resurfacing implants revised due to pseudotumors. J Bone Joint Surg. 2010;92B:356–361.

45. Lemons JE. Dental implant retrieval analyses. J Dent Educ. 1988;52:748–756.

46. Mathiesen EB, Lindgren JU, Biomgren GGA, Reinholt FP. Corrosion of modular hip prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73B:569–575.

47. McNeil PJ, Durbridge TC, Parkinson IH, Moore RJ. Simple method for the simultaneous determination of formation and resorption in undecalcified bone embedded in methyl methacrylate. J Histotechnol. 1997;20:307–311.

48. Mendelson KM, Schoen FJ. Heart valve tissue engineering: Concepts, approaches, progress, and challenges. Ann Biomed Engin. 2006;34:1799–1819.

49. Merritt K, Brown SA. Metal sensitivity reactions to orthopaedic implants. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:89–94.

50. Merritt K, Rodrigo JJ. Immune response to synthetic materials: Sensitization of patients receiving orthopaedic implants. Clin Orthop. 1996;329S:S233–S243.

51. Mitchell RN, Jonas RA, Schoen FJ. Pathology of explanted cryopreserved allograft heart valves: Comparison with aortic valves from orthotopic heart transplants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:118–127.

52. Mizuno S, Tateishi T, Ushida T, Glowacki J. Hydrostatic fluid pressure enhances matrix synthesis and accumulation by bovine chondrocytes in three-dimensional culture. J Cell Biol. 2002;193:319–327.

53. Moore WEC. Microbiology of periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1987;22:335–341.

54. Muratoglu OK, Greenbaum ES, Bragdon CR, Jasty M, Freiberg AA, et al. Surface analysis of early retrieved acetabular polyethylene liners: A comparison of conventional and highly crosslinked polyethylenes. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(1):68–77.

55. O’Neill WW, Chandler JG, Gordon RE, Bakalyar DM, Abolfathi AH, et al. Radiographic detection of strut separations in Björk-Shiley convexo-concave mitral valves. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:414–419.

56. Oral E, Christensen SD, Malhi AS, Wannomae KK, Muratoglu OK. Wear resistance and mechanical properties of highly cross-linked, ultrahigh-molecular weight polyethylene doped with vitamin E. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:580–591.

57. Peters MD, Polverini PJ, Mooney DJ. Engineering vascular networks in porous polymer matrices. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;60:668–678.

58. Plemons TD, Hovenga M. Acoustic classification of the state of artificial heart valves. J Acoust Soc Am. 1995;97:2326–2333.

59. Purdue E. Alternative macrophage activation in periprosthetic osteolysis. Autoimmunity. 2008;41(3):212–217.

60. Rabkin E, Schoen FJ. Cardiovascular tissue engineering. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2002;11:305.

61. Rabkin E, Hoerstrup SP, Aikawa M, Mayer Jr JE, Schoen FJ. Evolution of cell phenotype and extracellular matrix in tissue-engineered heart valves during in vitro maturation and in vivo remodeling. J Heart Valve Dis. 2002;11:308–314.

62. Revell PA. Biological causes of prosthetic joint failure. In: Revell PA, ed. Joint Replacement Technology. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead; 2008a;315–348.

63. Revell PA. The combined role of wear particles, macrophages, and lymphocytes in the loosening of total joint prostheses. J R Soc Interface. 2008b;5:1263–1278.

64. Rimnac C, Pruitt L. How do material properties influence wear and fracture mechanisms?. Journal of the AAOS. 2008;16(Suppl. 1):S94–S100.

65. Sanderson C, Bachus KN. Staining technique to differentiate mineralized and demineralized bone in ground sections. J Histotechnol. 1997;20:119–122.

66. Scales JT, Winter GD, Shirley HT. Corrosion of orthopaedic implants. J Bone Joint Surg. 1959;41B:810–820.

67. Schmalzied TP, Campbell P, Schmitt AK, Brown IC, Amstutz HC. Shapes and dimensional characteristics of polyethylene wear particles generated in vivo by total knee replacements compared to total hip replacements. J Biomed Mater Res (Appl Biomater.). 1997;38:203–210.

68. Schoen F. Interventional and Surgical Cardiovascular Pathology. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders; 1989.

69. Schoen FJ. Approach to the analysis of cardiac valve prostheses as surgical pathology or autopsy specimens. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1995;4:241–255.

70. Schoen FJ. Pathologic findings in explanted clinical bioprosthetic valves fabricated from photooxidized bovine pericardium. J Heart Valve Dis. 1998a;7:174–179.

71. Schoen FJ. Role of device retrieval and analysis in the evaluation of substitute heart valves. In: Witkin KB, ed. Clinical Evaluation of Medical Devices: Principles and Case Studies. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1998b;209–231.

72. Schoen FJ. Pathology of heart valve substitution with mechanical and tissue prostheses. In: Silver MD, Gotlieb A, Schoen FJ, eds. Cardiovascular Pathology. 3rd ed.) Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders; 2001;629–677.

73. Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Tissue heart valves: Current challenges and future research perspectives. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;47:439–465.

74. Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Calcification of tissue heart valve substitutes: Progress toward understanding and prevention. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1072–1080.

75. Schoen FJ, Titus JL, Lawrie GM. Durability of pyrolytic carbon-containing heart valve prostheses. J Biomed Mater Res. 1982;16:559–570.

76. Schoen FJ, Goodenough SH, Ionescu MI, Braunwald NS. Implications of late morphology of Braunwald–Cutter mitral heart valve prostheses. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984;88:208–216.

77. Schoen FJ, Anderson JM, Didisheim P, Dobbins JJ, Gristina AG, et al. Ventricular assist device (VAD) pathology analyses: Guidelines for clinical study. J Appl Biomater. 1990;1:49–56.

78. Schoen FJ, Levy RJ, Piehler HR. Pathological considerations in replacement cardiac valves. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1992;1:29–52.

79. Schwartz RS, Edelman ER. Drug-eluting stents in pre-clinical studies Recommended evaluation from a consensus group. Circulation. 2002;106:1867–1873.

80. Schwartz RS, Edelman ER. Preclinical evaluation of drug-eluting stents for peripheral applications Recommendations from an expert consensus group. Circulation. 2004;110:2498–2505.

81. Sobieraj MC, Rimnac CM. Ultra high molecular weight polyethylene: Mechanics, morphology, and clinical behavior. J Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2009;2(5):433–443.

82. Sobieraj MC, Kurtz SM, Wang A, Manley MM, Rimnac CM. Notched stress-strain behavior of a conventional and a sequentially annealed highly crosslinked UHMWPE. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4575–4583.

83. Sussman HI, Moss SS. Localized osteomyelitis secondary to endodontic implant pathosis A case report. J Periodontol. 1993;64:306–310.

84. Sutula LC, Collier JP, Saum KA, Currier BH, Sandford WM, et al. Impact of gamma sterilization on clinical performance of polyethylene in the hip. Clin Orthop. 1995;319:28–40.

85. Tower SS, Currier JH, Currier BH, Lyford KA, Van Citters DW, et al. Rim cracking of the cross-linked longevity polyethylene acetabular liner after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2212–2217.

86. USPHS. U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health Guidelines for Blood–Material Interactions. Bethesda, MD: NIH Publication No. 85–12185, National Institutes of Health; 1985.

87. van Beusekom HMM, van der Giessen WJ, van Suylen RJ, Bos E, Bosman FT, et al. Histology after stenting of human saphenous vein bypass grafts: Observations from surgically excised grafts 3 to 320 days after stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:45–54.

88. Wagner WR, Johnson PC, Kormos RL, Griffith BP. Evaluation of bioprosthetic valve-associated thrombus in ventricular assist device patients. Circulation. 1993;88 203–2029.

89. Walker AM, Funch DP, Sulsky SL, Dreyer NA. Patient factors associated with strut fracture in Björk-Shiley 60° convexo-concave heart valves. Circulation. 1995;92:3235–3239.

90. Weinstein A, Gibbons D, Brown S, Ruff W, eds. Implant Retrieval: Material and Biological Analysis. Rockville, MD: US Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards; 1981.

91. Wiggins MJ, Wilkoff B, Anderson JM, Hiltner A. Biodegradation of polyether polyurethane inner insulation in bipolar pacemaker leads. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;58A:302–307.

92. Willert HG, Semlitsch M. Reaction of articular capsule to wear products of artificial joint prostheses. J Biomed Mater Res. 1977;11:157–164.

93. Woolson ST, Milbauer JP, Bobyn JD, Yue S, Maloney WJ. Fatigue fracture of a forged cobalt–chromium–molybdenum femoral component inserted with cement. J Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79A:1842–1848.

94. Wright TM, Goodman SB, eds. Implant Wear: The Future of Joint Replacement. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; 1996.

95. Wright TM, Hood RW, Burstein AH. Analysis of material failures. Orthop Clin N Am. 1982;13:33–44.

96. Wright TM, Rimnac CM, Faris PM, Bansal M. Analysis of surface damage in retrieved carbon fiber-reinforced and plain polyethylene tibial components from posterior stabilized total knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70-A:1312–1319.

97. Wright TM, Rimnac CM, Stulberg SD, Mintz L, Tsao AK, et al. Wear of polyethylene in total joint replacements Observations from retrieved PCA knee implants. Clin Orthop. 1992;276:126–134.

General References

1. Fraker AC, Griffin CD, eds. Corrosion and Degradation of Implant Materials: Second Symposium. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM Special Publication, STP 859; 1985.

2. Ratner BD, ed. Surface Characterization of Biomaterials. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1988.

3. Revell PA, ed. Joint Replacement Technology. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead; 2008.

4. Shanbhag A, Rubash HE, Jacobs JJ, eds. Joint Replacement and Bone Resorption Pathology, Biomaterials, and Clinical Practice. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2006.

5. Transactions of the Society for Biomaterials Symposium on Retrieval and Analysis of Surgical Implants and Biomaterials. (1988). Snowbird, UT: August 12–14, pp. 1–67.

6. von Recum AF. Handbook of Biomaterials Evaluation: Scientific, Technical, and Clinical Testing of Implant Materials. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; 1999.

7. Weinstein, A., Gibbons, D., Brown, S. & Ruff, W. (Eds.). (1981). Implant Retrieval: Material and Biological Analysis. US Dept of Commerce, NBS SP 601.