Chapter III.2.2

Commercialization

What it Takes to get a Product to Market

Introduction

Previous chapters of this book cover technical and biological issues relating to biomaterials. Transforming a biomaterial into a commercial product with clinical utility is extraordinarily difficult. There are two major routes to commercializing a product: licensing it to an established company or creating a company to move it to market. In this chapter we focus on the latter pathway, but our discussion will also include the key elements involved in a successful license.

A business starts with an idea. And, like the mythical Pygmalion, those who come up with ideas have a tendency to fall in love with them. In the world of promising ideas, there are some which when brought to fruition make a significant difference, and those that have little impact. We urge the entrepreneur to test their idea against a list of important success factors to determine if it will have real impact. It is, after all, easy to find ideas that appear to have good business prospects, but ultimately very few have the potential for real market success.

A medical product must meet many criteria: it must be well-designed; fulfill complex regulatory requirements; obtain reimbursement; be appealing to one group of (often conservative) medical practitioners while able to withstand the attacks of other practitioners who may be working against its adoption. Failure of any of these is usually fatal to the product.

In this chapter we give aspiring entrepreneurs a basic introduction to the considerations they can use to size up an idea. But the subject is vast, and this introduction is merely a brief survey. Still, we hope that if you are seeking to commercialize a product, what follows will give you an entry point to the hard work you will need to do to honestly assess, modify or even discard your idea. We also hope that by giving you insight into how to increase your own chances of success, more clinically useful products will get to market, which will help us all.

Life science businesses fail for many reasons, including lack of financing and poor execution. But in our experience they most often fail because the idea driving the business premise does not provide sufficient value to the prospective customer or market. The chasm between an interesting idea and an idea with significant new value arises for many reasons, some of them quite predictable: an uncompelling need; the market size doesn’t justify the cost to bring the product to market; the idea infringes on other’s patents; there is no reimbursement. At the beginning of an enterprise, the team is setting out the blueprint for the next five-to-ten years of the company’s work. They have an obligation to carefully evaluate every facet of the future company. Problems such as those listed above can be identified at this early planning stage and, ideally, avoided. Then, the team should again evaluate the key risks to business success. This continuing circle – considering risks, evaluating them in light of the best available data and opinions, strengthening the plan, and doing it again – is critical if the team is to hit key milestones and be successful. Elucidating shortcomings early is a useful (though painful) task. It can save the adept practitioner from literally years of work chasing unproductive blind alleys to their inevitable, fruitless, conclusion.

The Need You Propose to Solve

There are techniques for developing ideas for medical products. One, based on the so-called Biodesign Process, was evolved by Paul Yock, Josh Makower, and others at Stanford (Zenios et al., 2009). The subject of an excellent textbook, their technique starts with fieldwork – observing real-life clinical procedures, and using those observations to uncover important needs and formulate novel solutions. This process from the start is designed around finding needs to solve, not ideas to solve them.

But that’s not what usually happens. More often, a scientist or inventor makes a discovery and starts thinking about how and where it can be applied. Many applications are considered, and chosen as much for whether the idea can be applied to them as whether they are worth solving. As a result, although it may seem too obvious to state, one must keep in mind that a new medical product must solve a clinical problem.

Developing something innovative and useful is not the same as solving an important need. For example, a new treatment for smallpox, while undoubtedly an achievement, is not the solution of an important clinical need (the possibility of bioterrorism notwithstanding), since the disease has largely been eradicated.

Although it is hard to give absolute rules, a solution to an important need might typically have some of the following characteristics:

• Provably decreases mortality or serious morbidity in an identifiable patient group;

• Substantially lowers the cost of treatment relative to the standard of care;

• Meaningfully improves an existing treatment by such things as filtering out patients who will be unresponsive or will have serious adverse effects;

• Makes an earlier diagnosis of an illness for which an earlier diagnosis means substantially better outcomes.

Less significant solutions often include the following:

• Early detection of conditions for which early detection confers no benefit or even worse, early detection of things that are not even provably connected with the condition;

• Improvement of patient comfort but not patient outcomes. Since payors typically will not pay for comfort, it will be hard to find a market;

• Small decreases in surgery time, especially when this comes at significantly increased cost.

Determining whether one solves an important need is difficult to do in a vacuum. It will typically require extensive research of the literature. One will likely wish to speak with clinicians to have them validate the idea’s value. Depending on the degree of protection, this may need to be done under non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), but to maximize the chances someone will speak with you. NDAs should be avoided if at all possible. Your goal, when all this has been done, is to very succinctly – ideally in a paragraph or so – write down the need you proprose to solve, explain why its solution is important, and in what ways your idea solves it.

Market Size and Growth

Although it is possible to develop a product for a small market, the size of the opportunity has an obvious impact on the amount of money that should be spent to develop it. Thus, it is essential to understand how large the potential market for your product/technology is, and how ready the clinical users will be to adopt it. This can be evaluated at the earliest stages of a project, and again when prototypes are available, when animal testing is done, at early clinical trials, etc. Important considerations include:

• The projected growth of the patient population (i.e., diseases of aging are likely to increase in aging populations);

• The number of procedures currently performed and the number of units sold;

• The current solutions, including how they are applied, their outcomes, their cost (especially reimbursed cost), length of time they take to use, and the tools and training they require;

• Whether your solution is incremental or a path-breaking replacement;

• The companies selling the existing solutions and whether your device complements their product line (i.e., appeals to the same markets without replacing their product) or competes with it;

• The path of innovation, and what the most likely new devices will be in one, five or ten years;

• The number of patients who COULD BE and are LIKELY to be served by your solution;

• The specialty that will use your solution, and whether this is a change from current practice.

Before an entrepreneur moves to exploring the numerous tactical business considerations, which we will outline in the section entitled “Business and Commercialization Issues,” they should gain insight into one more aspect(s) of the market: how the various constituencies will align in support of or against the proposed new product.

Effect on Various Constituencies

New products displace old ones, and disruptive new products upset complex webs of relationships and interests. In a business as complex and conservative as the healthcare industry, it is important to understand that introducing solutions also creates problems. For example, the arrival of percutaneously introduced vascular stents caused a dramatic shift in power between cardiac surgeons and interventional cardiologists, with surgeons being less than completely enthusiastic advocates of the new technology. In developing a new medical product, it is – perhaps surprisingly – not enough to simply improve patient care. You should also pay attention to how the new product will affect the interests of each constituency. For example:

• Patients: who balance ultimate results against recuperation time, likelihood of success, risks, and many other factors;

• Clinicians: whose concerns include patient safety, difficulty of learning to use the new product, and whether they – or a different specialist – control the patient workup;

• Insurers: who worry about the additional cost of new technologies, and risks to their competitive position if they fail to reimburse the technologies.

Clinical Trials

It is never too early to begin to understand the clinical trials a company will need to perform. Here is a short list of some of the reasons:

• Regulatory approvals often require clinical data;

• Reimbursement often requires proof of economic performance that can only be obtained through clinical trials;

• Marketing claims can often only be made after clinical trials have substantiated them;

• Investors are usually much more interested in investing in companies that have proven their product works. Additionally, investors are loath to invest in companies where the expected clinical trials will be long, large, and extremely expensive;

• Clinicians are much more interested in products for which there is clinical validation;

• Some products that would undoubtedly be valuable simply cannot be brought to market because the cost of the trials would be too high.

Clinical trials are generally the costliest initiatives undertaken by a life science company. But because a clinical trial needs to accomplish so many disparate objectives (viz. the list above) it is extremely important to design them as efficiently as possible, and to understand their purpose as early as possible.

Intellectual Property

A start-up’s most significant asset is usually its intellectual property (IP). Therefore, every start-up needs a strategy for developing, increasing, and protecting this key asset. Understanding competitive IP, and the strengths and weaknesses of your IP, are critical for fundraising and prioritizing all other expenditures.

Patents are expensive and slow to obtain. It can cost $10,000 or more to have a law firm file a US Patent. Even a provisional patent, which gives you the right to file an actual patent within a year, can run upwards of $2000. Initial responses (“office actions”) from the United States Patent and Trademark Office can take two years or more, and there is a long road to a patent following that. As a result, there is often a substantial gap between the time one starts a company and the time patents are in hand. During that time, founders must convince savvy investors that the company’s patent applications are likely to lead to issued, strong patents. The company must clearly understand the strength of their patent applications, and have an in-depth understanding of how they are superior to the competitive IP.

Selecting a strong patent attorney is crucial. Use advisers, investors, and the company board to get recommendations of at least three patent firms, and interview each to assess their expertise in the company’s scientific domain, their ability to be prudent advisors to the company, and the personal chemistry you will have in working with them. A good patent attorney will be a source of strategic IP advice regarding patents, including IP budget priorities. In some cases, IP attorneys will defer their fees for start-ups until the company has obtained funding.

There are alternatives to using patent attorneys, for example, filing a provisional patent is often straightforward work for a technical person. Another source of expertise is the patent agent, a technical person with additional training analyzing and preparing patents. An economical and effective approach is to draft the initial application oneself or with the help of a patent agent, and then have an attorney do a final review prior to submission.

It is also important to understand the patents close to your IP to ensure you have “freedom to operate,” meaning that you are able to build your device without infringing anyone else’s patents. Again, patent lawyers and patent agents can assist you. Much of this work can be done by the company founders, as long as they have good advisors.

Regulatory Strategy

It is far beyond the scope of this chapter to provide a detailed view of the regulatory process. Our purpose instead is to provide a basic understanding of the regulatory complexities, and an appreciation of the need to plan the regulatory strategy early. There are few things more critical to a life science company than its regulatory strategy and choices, and the better you understand the regulatory framework, and the earlier you understand your strategic choices, the greater your chance of success.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is committed to ensuring a product is safe and effective for its intended purpose. The level of FDA review is determined by the nature of the product, its indication for use, and the manner in which it is to be used.

Broadly speaking, in the U.S. medical products for human use are regulated under one of three divisions: drugs (Center for Drug Evaluation and Research or CDER); devices (Center for Devices and Radiological Health or CDRH); and biologics (Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research or CBER). Most biomaterial-based products will fall within CDRH. The device pathway through CDRH (or at times, CBER) is usually simpler, cheaper, and faster than the drug pathway.

CDRH regulates how a device can be brought to market, and what controls are placed on the marketing and manufacturing of the device. The manner in which a device can be brought to market depends first on the device classification (I, II or III), and to a lesser extent on the CDRH medical specialty panel that will be reviewing it. This, and a great deal more about the regulatory framework, is explained in further detail at the FDA website, www.fda.gov.

Class I devices – such as bandages, adjustable beds, many surgical instruments, and manual stethoscopes – are deemed to pose minimal risk to patients and are therefore regulated most lightly. Such products can usually (count on exceptions in the complex regulatory world) be brought to market without any advance approvals or clearances from the FDA. Additionally, the company will be subject only to a set of general rules (“general controls”) about how the product must be labeled, registered, and manufactured.

Class II devices – e.g., mercury dental amalgam, electronic stethoscopes, most catheters, needles, and monitoring devices – pose higher risks than Class I devices. They must usually be cleared in advance by the FDA before they can be brought to market. This is done by the 510(k) premarket notification process, the overwhelmingly dominant path to the US market for complex medical devices. A 510(k) clearance can often be completed in months, usually without clinical trials, and is relatively inexpensive.

To receive a 510(k) clearance, one must usually show that the device is “substantially equivalent” in safety and effectiveness to one or more “predicate” devices. There is a great deal of misunderstanding about what are true predicates, and substantial art and skill in selecting appropriate predicates and preparing a submission under the 510(k) rules. Thus, this is usually done with the help of experts.

Class III devices – including devices that are life-sustaining, such as cardiac assist pumps and also most implants such as bone grafts, heart valves, orthopedic implants, arterial grafts, and pacemakers – are regulated most strictly. The FDA requires Class III devices to undergo a more elaborate approval before allowing them on the market. This so-called Pre-market Approval (PMA), requires a minimum of 180 days, and often a year or more, to issue after submission of significant amounts of data, and typically will require many millions of dollars in preclinical and clinical trials. One of the hurdles to surmount is that the device must typically be tested in a pivotal human trial of effectiveness, and this trial must be conducted under an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE).

Many other countries have their own regulatory approval bodies. In the European Economic Area (EC), a manufacturer can market a device when it has received a CE (“Conformité Européenne” or “European Conformity”) mark, meaning that the manufacturer’s product conforms to applicable EC directives. Many other countries, including China, piggyback on the United States regulatory system, and in such countries, US FDA approval is sufficient for a manufacturer to bring their product to market.

Entrepreneurs should keep the following regulatory considerations in mind:

• In the US, a company must carefully plan its regulatory strategy and be sure the FDA is comfortable with corporate marketing strategies. In particular, before approval do not be vague about product claims in your product manuals or literature. Instead be transparent in your intent, document your work meticulously, and work with the FDA to make them comfortable with your approach.

• Don’t cut corners with the rules. For example, if you believe your device can be shoehorned into Class I as a wound cover, but your intent is to use it in brain surgery, you are likely at some point to face significant regulatory problems and delays, and your business may be shut down. It is far better to confront the issue head on and seek an advance determination that your product is, indeed, Class I.

• As elaborate as the regulatory infrastructure is, it is not algorithmic. Often regulatory consultants or even FDA insiders will disagree on how something is regulated. Thus, there can be significant value to managing your approach intelligently and carefully.

• Understand the regulatory framework around your product as completely as you can. Among many reasons for this, investors expect that entrepreneurs will have thought a great deal about this critical aspect of a product.

• FDA regulations are enabled by law, but evolve by agency action. They are in constant flux (currently the most notable example being the 510(k) regulations), so keep abreast of these changes through trade organizations, current FDA news, and by working with experienced consultants.

Because of the aforementioned complexities, companies are increasingly introducing their products outside the US where regulations are easier to comply with and approvals are faster.

Reimbursement

In the United States, most medical expenses are paid by healthcare insurance, and so insurance carriers are a crucial part of the medical market infrastructure. Business plans from companies in the 1990s rarely discussed reimbursement because it was assumed that a superior product desired by the clinician would be paid for. But this has changed dramatically as medical costs have escalated. While drugs, once approved, have a very favorable reimbursement profile, medical devices, even when approved, often face a complex and uncertain reimbursement process. Nevertheless it is never too early to obtain an understanding of the reimbursement landscape, because without adequate reimbursement a product will be doomed.

Very generally, reimbursement within the US falls into one of four bins:

• Unreimbursed “self-pay” procedures, such as cosmetic surgery, typically paid for by the patient;

• Physician services, described using CPT (or its synonym, HCPCS level I) codes and reimbursed by the insurer (Medicare or others) based on how they wish to pay for these services;

• Hospital admissions to treat a condition, typically reimbursed by Medicare (and often other insurers, though with different payment amounts) as part of a single fixed payment to the hospital (which of course in the complex world of reimbursement can change subject to various factors) under a diagnosis-related-group or DRG, and a separate CPT-based payment to the physician;

• An outpatient-based procedure performed in a hospital or ambulatory surgical center, reimbursed by Medicare (and often other insurers) using one or more ambulatory procedure codes (APCs) which are like DRGs with the notable exception that several APCs can be stacked together for a single patient visit.

Subject to insurance regulations and its own commitments to its clients, a private insurer has great latitude to set its own reimbursement levels for any particular product or to not reimburse it at all. However, broadly speaking, private insurers follow Medicare, and therefore obtaining Medicare reimbursement is critical for a new product.

There are several general business considerations to keep in mind which will make the reimbursement environment easier to negotiate.

• Some devices are used in a self-pay indication. In such a case, with no insurer, there is no reimbursement issue (although of course self-payers also care about cost).

• Products used as integral parts of existing DRGs or APCs – for example, an improved heart bypass pump for cardiac surgery – have narrowed reimbursement concerns. Perhaps the biggest risk is that the new device fundamentally changes the procedure, thereby bumping it into a different DRG or APC, or worse, transmuting it into something no longer covered under any DRG or APC. Assuming this is not the case, customers will care about the value the new product adds to the process – reduced procedure time, lowered co-morbidities or hospitalization time, perceived importance of the product by clinicians and even patients, and so forth – compared to its cost.

• For new services and procedures which require a CPT code, the code may already exist and be reimbursed. But keep in mind, a CPT code is not a guarantee your product will be reimbursed. For example, if a product dramatically changes how a procedure is applied, perhaps by substantially enlarging the pool of patients who will receive it or allowing a different specialist to perform it, insurers may reconsider reimbursement. That is one reason why experienced investors look carefully when device entrepreneurs claim their new product fits into an existing code.

• Each country has its own reimbursement process, and different payers within countries have their own processes.

When a product is unreimbursed, in many cases the entrepreneur may need to obtain a CPT or DRG code. This alone can be an extended multi-year process, often longer than the regulatory approval process. And unlike the regulatory process, with its established (mostly followed) timelines, there are no such schedules for the reimbursement process. In the current cost-constrained environment, there is negative pressure to add expensive new procedures. Some of the things required to obtain reimbursement include:

• Determining who makes reimbursement decisions at each payer;

• Describing the clinical and economic value of the proposed product/procedure, including key economic benefits and consideration for the proposed new reimbursement;

• Indicating how this procedure will affect total costs;

• Collecting clinician feedback on the proposed product/procedure;

• Performing clinical trials of the new product, including the economic issues as part of the study;

• Publishing the clinical results showing the economic value produced by the new product;

• Getting regulatory approval of the new product;

• Having the new product used by many practitioners in the use indicated;

• Getting support from clinicians, key opinion leaders, and medical societies;

• Obtaining relevant codes from the American Medical Association (AMA) or Medicare.

For these reasons, obtaining anything remotely close to national reimbursement (i.e., from Medicare and most insurers) for an unreimbursed product can take years. The process is quite expensive for two reasons: first, the actual cost of obtaining reimbursement; and second, the difficulty in convincing practitioners to use a product without an automatic reimbursement. Thus, it is critical for small companies to work with experienced reimbursement experts. And if a company needs to obtain new reimbursement codes, the experts may well need to be retained full-time on staff.

Business and Commercialization Issues

Once you have confirmed a compelling unmet need in a large market, understood the regulatory and reimbursement issues, and considered the clinical trials your company will need to perform, you have done your basic due diligence. If your idea has passed muster, congratulations! But running a business brings a number of other issues to the fore which you should consider (Figure III.2.2.1).

Figure III.2.2.1 Steps to commercialization.

Funding

Developing a new product employing a biomaterial technology is an expensive and time-consuming process. Table III.2.2.1 shows an example of a typical timeline for development of a PMA product within the United States. Many start-up companies do portions of this work outside the US to save time and money. Nevertheless, the steps, approximate times, and rough budgets are good guidelines for 2012.

TABLE III.2.2.1 Sample Timeline & Budget for Development of a PMA Product within the US

IDE: Investigational Device Exemption.

IRB: Institutional Review Board.

PMA: Pre-market approval.

During the development stages of a company, moving quickly and meeting the key milestones of the project plan within budget are critical to having adequate resources to succeed. Since a medical business rarely has revenues during the development stages, raising capital is essential. Below are the three major sources of capital you are likely to encounter. Keep in mind that the earlier investors typically incur the highest risk, and therefore rightly expect the highest potential returns.

• Friends and family (sometimes jokingly referred to as “three f” financing: friends: family: and fools). This includes unpaid “sweat equity” put in by founders. Typical amounts are tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars;

• “Angel Investors,” often wealthy individuals who have made money in business and enjoy the chance to make money or become involved in new start-ups. They will typically invest hundreds of thousands to low millions of dollars in a venture;

• Professional investors or Venture Capitalists (VCs) who manage large pools of money, and are often seeking companies of a stage and type able to use millions of dollars, which of course requires an eventual payback of tens to hundreds of millions of dollars.

A business without funding will not likely survive. Therefore, an entrepreneur should learn about the funding process early. This is an extremely intricate topic, and we offer one hopefully useful tip: call potential funders before you are actually looking for money to solicit their advice and get to know them. Then when you are actually looking, they can calibrate your progress, and also you are a known entity. Three more tips:

• If possible, do not cold call these funders. Network first to clinicians and scientists in the field. Many of them may know investors and can arrange introductions. Use the initial investor’s introductions to obtain other introductions.

• Use care before approaching professional venture capitalists. If your idea has major holes or you lack experience, it would be better to hone your approach a bit first.

• Spend time understanding, as deeply as possible, the various factors described in this chapter. Savvy potential investors will care about all of them, and will be reassured when they meet a CEO who has really thought through the business.

Business Model

A business model refers to the method a company will use to make money from its product. Although it may seem straightforward, there are usually many ways to bring a product to market, and it usually takes a great deal of effort to determine the best one.

Considerations that can affect the model include: resources available to the company; relevant experiences of the team; buying patterns of customers; rate of product adoption in the marketplace; and the value of the product to each stakeholder. Some of the approaches used in medical device business models include the following.

Direct Sales

The company sells its products directly to end-users. Although this typically captures more value for a company than licensing, it is very expensive and can be slow to ramp-up to levels sufficient to support the company. Additionally, products must generally be expensive with high margins to warrant the cost of direct selling, as even a single sales call – which is often unsuccessful – can cost hundreds to thousands of dollars.

Recurring Revenue

In a recurring revenue model, the company has a continuing stream of revenue from a product. There are numerous ways to do this, including disposables, service contracts, leases, and tolls. Most innovative medical devices use some method of obtaining recurring revenues.

Disposables

Some products, such as surgical instruments, are purchased once and used multiple times. Others, such as hypodermic needles, are purchased, used, discarded, and replaced. Still others are purchased once and require additional components every time they are used. For example, many diagnostic instruments require reagents or special disposable sample holders. Such recurring revenue can be very attractive to a small company, amplifying the initial sale many times over a product’s life.

Service Contracts

Another source of recurring revenue is to add a service component to expensive capital equipment. Such service costs can be in the range of 10–15% per year.

Leases and Tolls

One way of lessening a customer’s cost for a product or converting it from a capital expenditure to an expense is to lease it or rent it on a per use basis or for a fixed number of prepaid uses. This model is especially suited for expensive imaging equipment, monitoring equipment, complex pumps, dialysis equipment, and the like.

Licenses

Companies that cannot or do not want to bring a product to market themselves can license it to another company for commercialization. A license agreement often includes an upfront licensing fee with recurring royalties for product sales. This can be a good way to create revenue, particularly in markets and geographies that the company will be unlikely to enter for an extended time. One danger is that a license necessarily involves a company giving up certain rights (such as exclusivity) to others. By doing so, it may diminish its value to potential acquirers or prospective partners who desire these foregone rights.

Development Strategy

Operations

“Operations” often refers to manufacturing, but also includes a wide variety of other tasks involved in running a business. These include purchasing materials, delivering products to customers, managing employees, and keeping track of product costs and capital expenses. For capital equipment product sales, “operations” generally includes managing installation, warranty, and ongoing service updates, and for software products it would include installation, assurance of compatibility, training, and ongoing support and upgrades. The comments below refer specifically to issues related to the manufacture of biomaterials products and implants.

Key Operations: Keep them in House or Outsource?

One of the critical questions a start-up faces is whether to keep operations in house or outsource them. This can have day-to-day implications, but also larger strategic ones. For example, if a business expects to eventually be acquired by a larger company, generally the acquirer will have their own operations expertise, and therefore will not pay more for a start-up’s operations. Developing operational capacity and expertise for biomaterials and implants requires significant effort, capital, and management attention. These are the reasons that most small companies find a partner to manufacture their products. However, in spite of these costs and complexities, start-ups with novel biomaterials often find it important to create unique processes for efficient manufacturing and repeatable product performance. Developing these finicky processes may take significant expertise and multiple iterations to assure a stable, repeatable, predictable, and affordable outcome, and the novel processes themselves then become part of the IP of the company, covered either by patents or trade secrets. In such cases, developing operational expertise internally builds a valuable asset of the company, and often is necessary for the success of the venture.

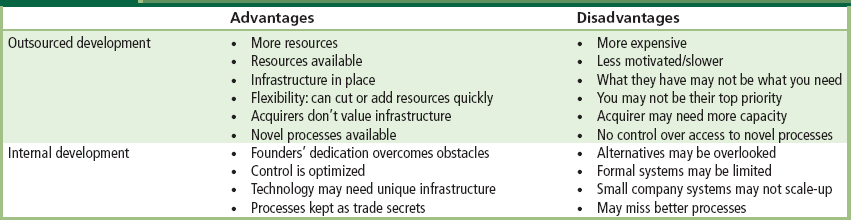

Even in companies that have outsourced the bulk of their operations, it is critical to have adequate and experienced oversight. Materials suppliers must be qualified, and contracts and oversight must be in place to ensure consistent quality, traceability, and delivery. Failure at any point in the supply chain with these partners will result in product problems for the start-up company. For a summary of these basic considerations, refer to Table III.2.2.2.

TABLE III.2.2.2 In-house or Outsource: Basic Considerations

Sales and Marketing

“Sales” is the process of offering the product to a purchaser. This includes: finding the initial leads; setting up meetings; demonstrating the product; enlisting users to speak with potential purchasers; working with purchasing departments and committees; and doing whatever else it takes to get the sale made! Marketing involves developing the value proposition for a product – that is, the economic and other benefits to be gained by using it – and communicating that inside and outside the company. The marketing department performs the product management function – identifying strategies for locating customers, preparing literature and other support materials for the sales department, and helping develop new product ideas based on the market feedback it obtains. One important thing to keep in mind is that a marketing department is very limited in the claims it can make about a regulated device, unless it can prove those claims are true. The best way to do that is by clinical trials; therefore, it is very important to involve the marketing department in clinical trial design early in the process to ensure they can make the claims they require.

Although sometimes people confuse sales with marketing, the function of marketing is to lay the groundwork of building tools to communicate what the product does and locating customers so the sales department can sell to them. Experience from large companies demonstrates the value of using dedicated salespeople to call on potential customers and build long-term relationships with them as a prelude to selling them products. But it is a rare start-up that can afford both a dedicated marketing department and full-fledged internal sales effort. Therefore, start-ups should consider a number of alternatives for selling.

The most obvious sales model uses employees as salespeople. Unfortunately, this can be very expensive, requiring management, salary, expenses, training, and additional sales resources. Additionally, the company must be prepared to wait for possibly a long period of time before it will see significant revenues from a salesforce.

Manufacturer’s representatives (or “reps”) are independent business people who sell products made by different manufacturers. A rep typically works in a defined geographical region and works on commission. Reps generally know their customers well, know the buying processes in the healthcare entities they visit, and get paid when products are sold. They provide affordable selling outreach and greatly expand the sales territory a company is able to cover. But reps, who need training and management in the product, have divided attentions because they usually sell multiple products from many companies. Thus, they rarely provide the “missionary” effort required for acceptance of a novel product, and can lose confidence if a product does not catch on quickly. Finally, in the event a company wishes to restructure a sales effort, rep contracts can sometimes make that difficult.

Stocking distributors purchase products directly from a company at a significant discount, typically 30–40% of the expected sale price. Distributors tend to specialize in particular medical areas, creating extensive catalogs of products which they sell. The distributor maintains an inventory of products, and handles the shipping and billing to the customer. The distributor will have its own sales staff, with each salesperson responsible for various accounts and/or various product lines. In the United States, a distributor will often have sales people in an entire state or region, giving them a strong sales footprint. Because distributors may carry even more products than sales reps, they can be even harder to motivate, and one complaint companies have about distributors is that they don’t sell, but “merely” take sales orders from customers who call them.

Due to the increasingly difficult regulatory environment in the United States, companies are increasingly looking to introduce their products abroad. Because the cost and complexity of selling a product in another country can seem even more daunting to a start-up than selling in the US, international sales almost always begin with international distributors. There are substantial, experienced, and knowledgeable distributors in many countries. Even so, a start-up will likely need to dedicate a full-time experienced professional to finding and managing the international distributors.

Team

Founding a company is an intensive process that takes dedication, perseverance, and a dogged determination to overcome innumerable obstacles. A company includes a number of individuals, each with different skills. The first people to come on board are, by definition, founders. Usually founders of a biomaterials start-up will have either a technical or marketing background. This is because the key assets in a start-up are typically IP (technical), understanding of the unmet market need/value proposition (marketing), and the ability to inspire others to invest in the company (often marketing, sometimes technical).

The Chief Executive Officer (CEO) has the most critical job in a company. The CEO plans and explains the company’s strategy, obtains (often through investors) the money and other resources the company will need, and hires and manages the team who implements the strategy. An experienced, charismatic CEO can plan on spending the equivalent of a full-time job raising money and working with the investors for the first two or three years of the company’s active life. Unfortunately it is not uncommon for the first CEO to initially be, or eventually become, an inappropriate fit for the company. In part that is due to the fact that many CEOs are brought into a company by “being there” as a founder or an acquaintance of the founder. Such accidents of proximity by no means insure that such a person has the appropriate skills to run a company, especially as the company’s needs evolve.

Assuming adequate financial resources, the CEOs key job is to hire the best team possible to implement the strategy. This will include consultants and employees. Early strategic experts in areas such as regulatory will likely be consultants. Working part-time they can develop the regulatory requirements for product development, bench and animal testing, and clinical trials. The first hires will be in key positions critical to the company’s success, such as R&D. Later hires will include marketing, regulatory, clinical, reimbursement, and operations staff. The CEO is constantly balancing the budget with the timing for adding other personnel.

A board of directors is not only statutorily required for companies in most states, but is also required by many investors, who will often demand one or more seats on the board (and investors should strive to balance this with an equal number of independent directors). But a good board does more than just fulfill these obligations. It also provides a pool of connections and expertise for the CEO to draw on as needed, and provides needed oversight to ensure the company stays on track. Generally the best board members have deep experience in the field, and significant operational expertise as CEOs or general managers. Investing board members often receive no stock, but independent board members typically receive 1–4% of the company for their service.

A board of scientific or clinical advisors validates the company’s science and product. For a company with a superb idea, it is not difficult to recruit a top-notch board. Often, clinicians and scientists are extremely approachable and interested in new products for patient care. These boards usually meet three or four times per year, are available for advice to the team at other times, and often are the first users of new devices in animal or clinical tests. Advisors will typically receive a small amount of stock in return for their services.

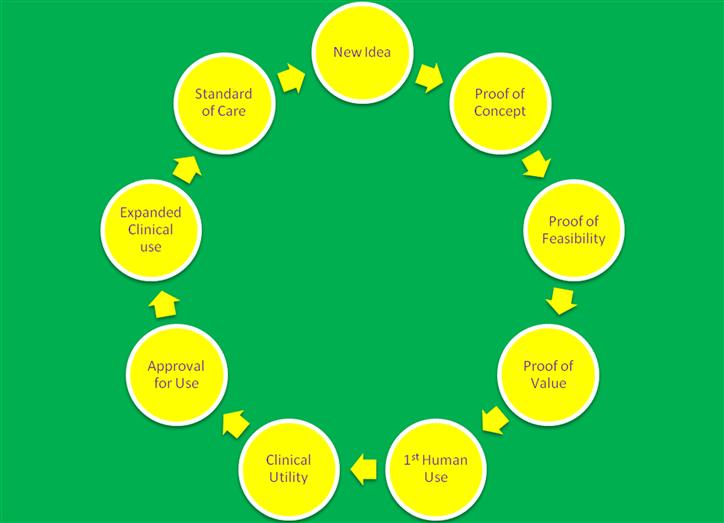

The Stages of Life Science: From Concept to Adoption

As a company grows, it will need ever increasing amounts of capital, and for this to occur with minimal pain for all concerned, investors will expect to see the value of the company continue to climb as new investments are brought in. Generally this means the company must continually be reducing the chance of failure. To be clear: successful management of a medical device company is about progressively eliminating risk. There are various reasonably well-defined risk-reduction stages in a medical product’s life cycle (Figure III.2.2.2), each with its own considerations. They are set out below.

Figure III.2.2.2 The Circle of Life in a Life Science Company.

Idea

In the idea stage, the entrepreneur is first and foremost dedicated to ensuring their idea solves a real problem. Assuming so, this is the stage to read and absorb the medical literature, learn about patients and treatments, and investigate the competitive products and the IP around those products. It is also a good time to start expanding on the idea to understand how it will: work in practice; actually be turned into a product; and provide clinical value. This is the time when the successful entrepreneur will be starting the never-ending process of stress-testing the idea against the considerations put forth in the beginning of this chapter: need; market; clinical trials; intellectual property; regulatory; reimbursement. Before in-vivo or even in-vitro testing, this is the time for the successful entrepreneur to start the “in-cerebro” work, that is, the never-ending process of stress-testing the idea against the considerations put forth in the beginning of this chapter: need; market; clinical trials; intellectual property; regulatory; reimbursement.

As the idea progresses to an invention, it is important to follow best-practices such as capturing the idea as clearly and completely as possible in writing and with sketches and three-dimensional computer models for use when filing, and perhaps defending, patents.

Proof of Concept

This milestone is achieved when the entrepreneur can demonstrate to themselves and their advisors that the invention can work. One should select the fastest, most cost effective, and elegant tests sufficient to convince a critical but friendly expert of the validity of the idea. The demonstration will involve science, but selecting the appropriate demonstrations is certainly an art.

For example, in a percutaneously delivered cardiac valve replacement, making a structure that can be folded sufficiently small and then expanded in place is doubtless a critical test. For anti-microbials, demonstrating that their presence in agar plates prevents bacterial growth may be compelling. Be creative and wide-ranging: consider crude prototypes in cadavers; animal parts purchased from butcher shops; bench simulations; mechanical testing; and so forth. As the saying goes, one dumb experiment is worth ten expert theories, so build things that can be tested. No matter how crude your prototypes, you will learn from these tests.

Sometimes one can develop very clever ideas for testing something. For example, it may be possible to try an early prototype product implant in a patient who is going to have an amputation. A device to treat morbid obesity could be placed for a short while in patients who are being prepared for stomach reduction surgery. In general, the better a concept is tested in simulated yet valid tests, the more compelling the value proposition becomes.

Proof of Feasibility

Proof of concept is achieved by convincing your “insiders.” Proof of feasibility, by contrast, is achieved by convincing multiple, skeptical, outsiders. To do this, a product must be fabricated in small quantities and tested in a controlled biological model. Although the product should be reproducible, it will not likely be fabricated in any sort of production environment. The emphasis should not be on reducing cost or manufacturing complexities, or improving shelf-life or human factors. Instead, the point is to develop the most expeditious, inexpensive ways to make small quantities so preliminary clinical testing may begin.

Animal Models

If there is an available predictive animal model, it can be an excellent vehicle for feasibility testing. One should spend time learning the intricacies, strengths, and shortcomings of various models. For example, porcine (pig) models are often favored for cardiovascular testing due to the similar reactions pig and human blood vessels have with biomedical devices. Canine models may not be good for testing thrombogenicity since dogs have more aggressive clotting mechanisms than humans.

Short-Term Results

If there is no animal model suitable to test your invention, it may be possible, as described above, to perform short-term human testing to get valid data on device performance.

Proof of Value

This milestone ties the theoretical functioning of a product to the practical requirements for using it. A device or technology may work, but may take so long to use or be so difficult to deploy that only the most skilled practitioners can use it effectively. For example, if a new knee replacement requires more precise alignment in the receiving bones, most practitioners may be unwilling to use it. Proof of value involves an exploration of whether, all things considered, the product adds value. Considerations include time to perform the procedure, expertise required, practice patterns, patient comfort, and time for rehabilitation, likelihood of adverse outcomes, and so forth.

Although it may still be possible to fine-tune the product and procedure to enhance value and manage the risks and unintended consequences, this is the time for an honest, unflinching look by the team and their advisors, to determine whether the product is likely to be useful, and therefore successful in the market.

First Human Use

This is a really big milestone, with significant implications. It means the company has managed to persuade an Institutional Review Board (IRB) to allow the device to be used on patients, and has received an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) from the FDA. The company has also persuaded one or more clinicians to use it and will soon see how it performs, in the target population, under the intended procedure.

First human use is often performed outside the United States, since other countries typically have a shorter review and approval cycle, lower costs, and faster patient recruitment. In addition, in the event a start-up must make modifications to its device or protocol after these trials, there will often be less adverse publicity than if the trials occurred in the US.

Validation of Clinical Utility

Validation of clinical utility occurs upon early statistical confirmation of what had heretofore been anecdotal evidence of product and procedural value.

Trial results from the initial human use site provide the first data used for this validation. This data – including description of device, protocol, clinical outcomes, economics, post-procedure recovery, and other parameters of the trial – is measured, captured, and made available for others to review. While early clinical adopters may be willing to use devices that have limited human use, the average practitioner will wait for test results from numerous users at several institutions. And the more serious the indication, the more conservative the average practitioner will be.

The difficulty is that some devices – especially biomaterials-based ones – can require extensive time and large numbers of patients for true validation. A new drug-eluting stent will take at least 6–12 months (perhaps more) of patient follow-up in hundreds or thousands of patients before most clinicians will have confidence in its performance. A new orthopedic implant may take many years before the true story is known.

Approval for Use

This occurs upon clear and unequivocal receipt of notice from a regulator that the company is cleared for commercial launch. For more information, see the “Regulatory Strategy” section above.

Expanded Clinical Use

The product is in general market release, in use by mainstream clinicians. It has been estimated that 5–10% of clinicians can be characterized as “early adopters” willing to use a product before it is widely accepted. But mainstream users need more. They rely on things such as testimonials from one or more early adopters, discussion at medical conferences, and journal articles. The product still requires user training and sales, but there is much less “missionary” selling; most potential users are aware of the new technology, and it requires just a little bit of persuasion to give them the confidence to try it.

Standard of Care

By this phase, the product is in widespread use by mainstream clinicians as part of their standard patient practice. By the time a product has achieved this market-leading milestone, it usually will have large competitors making knock-offs with incremental or substantial improvements. One sure indication that a device or technology has reached this milestone is when the device and related procedures are taught in medical schools and residency programs. But by then, the start-up is no longer a start-up. It will have typically sold the business or licensed the product to a large medical device company or in rare cases will be a large company itself.

The Next Phase

A new idea or invention! And the cycle begins anew.

Bibliography

1. Zenios S, Makower J, Yock P. Biodesign: The Process of Innovating Medical Technologies. 1st ed MA, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2010.