Chapter III.2.6

Corporate Considerations on Biomaterials and Medical Devices: Case Studies in Regulation and Reimbursement

As previous chapters have demonstrated, developing a new medical device for the US market is a complex process. Certainly, most Class II (moderate risk) and Class III (high risk) devices require US Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiologic Health (FDA CDRH, often just called “FDA”) notification or premarket approval. The premarket submission requires that Good Manufacturing Processes (GMPs), including design controls, be followed. For Class III devices, significant manufacturing controls must also be applied. The manufacturing facility of the new device must be registered, and the device listed. The FDA often inspects the manufacturing facility as part of the approval process. Depending on its market, a new medical device often needs medical and private health insurance reimbursement, so that potential end users can afford to purchase the device. Finally, the US Patent Office (USPTO) requires that claims for a new invention be filed within a year of first public disclosure (often, the offer for sale), in order to protect the invention.

In this chapter we discuss these important issues, within the context of biomaterials for medical devices. Many of these issues are also covered in other chapters, so we focus here on case studies of design controls, described in more detail in Chapter III.2.3, which comprise the fundamental requirements for development of a new medical device. Case studies exemplifying the different considerations for an electrocardiogram (ECG) electrode, a tissue heart valve, and a permanent skin substitute material are highlighted.

Regulatory Strategy

When a product development project is first initiated, it is prudent to determine the regulatory strategy as early as possible, in order to facilitate project planning. Class II devices require less time and resources for a 510(k) submission than do Class III devices for a premarket approval (PMA) submission. A combination product (device + drug, device + biologic) may not even be regulated as a device, but rather as a drug or biologic. Often, a Request for Designation is made to the FDA Office of Combination Products (OCP). If possible, a manufacturer tries to have a specific combination product designated as a medical device, because regulatory requirements are less substantial compared to those for a drug or biologic.

After the determination has been made that CDRH is the appropriate regulatory center, the company’s regulatory department must decide if the device is Class II or Class III. As of 2009, for a Class II device, such as an ECG electrode, one predicate device or a group of predicate devices, whose lineages can be traced to substantially equivalent devices released in the US before May 28, 1976, must be determined. These predicate devices must not currently be considered Class III devices. Most implantable devices have been designated as Class III. A truly new type of device is classified as Class III by default.

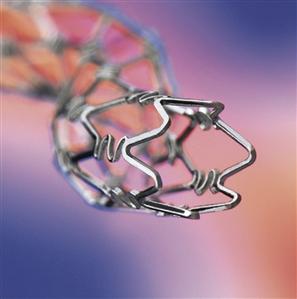

Cypher® Stent Regulatory Strategy

Johnson and Johnson’s Cordis division developed the first drug-eluting stent that received FDA approval. Each Cypher® stent (Figure III.2.6.1) consists of a stainless steel mesh tube, treated with parylene C, and covered with a basecoat and topcoat. The basecoat is formulated from sirolimus and two polymers: 67% polyethylene-co-vinyl acetate (PEVA) and 33% poly n-butyl methacrylate (PBMA). A drug-free topcoat of PBMA enables controlled release of sirolimus over 90 days. Based on in vivo study data, sirolimus inhibits smooth muscle cell migration andproliferation, which aids in the prevention of restenosis (Cordis, 2003).

FIGURE III.2.6.1 Cypher® Coronary Stent (Cordis Corporation, Bridgewater, NJ, USA).

In its Request for Designation to the FDA OCP in 2000, Cordis stated that the primary mode of action for a drug-eluting stent is to provide: “a mechanical buttress that resists mechanical compression,” while a coating on the stent serves “the ancillary purpose of retarding formation of intimal hyperplasia.” The FDA agreed with this request, and designated CDRH as having primary jurisdiction (OCP, 2000). Cordis filed its Cypher® PMA submission, P020026, on June 28, 2002, and quickly responded to 24 separate requests for additional data by filing corresponding amendments. It received premarket approval for the Cypher® stent on April 24, 2003 (CDRH, 2003a), a total of 300 days.

Whenever possible, Class II status is preferable. Compared to a PMA submission, a 510(k) submission does not require clinical data or manufacturing data. Further, a 510(k) is less expensive to file, and less time is required until the FDA issues its premarket clearance decision. For the fiscal year 2009, the 510(k) and original PMA review fees were $3695 and $200,725, respectively. For fiscal year 2006, the most recent year with available statistics, 510(k) submissions required an average of 95 days between filing and notification. Similarly, original PMA submissions that were approved required an average of 335 days between filing and approval (ODE, 2008). It should be noted that the original PMA approval time for a new type of device, with which the FDA has no previous experience, may easily extend from the 335 day average by additional months, if not years. Approval may require the majority vote of an FDA Advisory Panel. For example, Gensia’s GenESA device, which was the closed loop infusion device for the new drug GenESA, required 44 months until CDRH approval (CDRH, 1997a).

Medicare Reimbursement

Equally important to the regulatory strategy is the product’s Medicare reimbursement strategy, assuming that reimbursement is critical for product success. Overwhelmingly, Medicare’s national reimbursement decisions are adopted by private insurance carriers. Moreover, more clinical studies may be required for reimbursement than for FDA approval. Therefore, it is prudent to begin planning for all these studies, potentially with study overlap, as soon as possible.

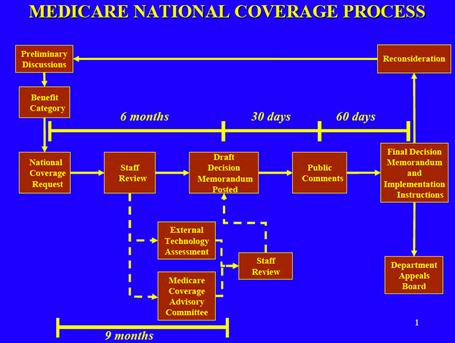

The national Medicare coverage process for a new device that is not currently reimbursed generally takes one year. The manufacturer of this new device meets preliminarily with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), and then submits a formal request for National Coverage Determination (NCD). The formal request must include a statement of desired benefit categories, as well as supporting documentation such as the PMA summary of safety and effectiveness data, any 510(k) predicate devices, and a description of any other clinical trials in progress. Within 90 days of receipt of the formal request, CMS determines whether or not to accept the request. If the request is accepted, another 90 days passes, during which CMS accepts 30 days of public comment on the device and, if necessary, generates an internal health technology assessment. The technology assessment may extend this 90 day timeframe. At the end of this 90 day period, a proposed decision memorandum is issued.

During the first 30 days after the proposed memorandum is issued, the public may comment. Within 90 days of when the proposed decision was issued, a final decision memorandum is issued. If the decision is made to provide coverage for the device, CMS makes this payment change effective within 180 days of the issuance of the proposed decision memorandum. A final decision may be reconsidered or appealed by the manufacturer or any other interested party, such as an insurance carrier or individual. CMS’s illustration of the National Coverage Determination process is shown in Figure III.2.6.2.

It is also possible to apply for local Medicare coverage with each of 10 Medicare regions.

Cypher® Stent Medicare Reimbursement Strategy

Separate from the National Coverage Process, Cordis requested a new payment code for reimbursement of the insertion of drug-eluting coronary artery stents. Cordis argued that: “due to the absence of restenosis in patients treated with the drug-eluting stents based on the preliminary trial results, bypass surgery may no longer be the preferred treatment for many patients … Lower payments due to the decline in Medicare bypass surgeries will offset the higher payments associated with assigning all cases receiving the drug-eluting stent.” The request was made in the early 2002 timeframe (CMS, 2002b), before FDA approval of the Cypher® stent. CMS solicited comments about the requested procedure code in the Federal Register on May 9, 2002, and approved a new code (effective October 1, 2002) on August 1, 2002 (CMS, 2002a).

Design Controls

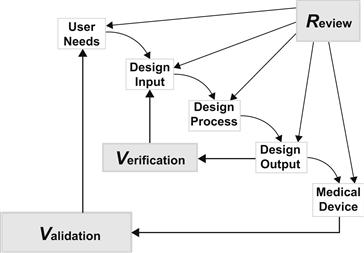

During the course of a product development project, design controls are mandated by the FDA. As shown in the illustration of the Waterfall Design Process (Figure III.2.6.3), a product is developed in response to user needs.

The process includes design inputs, the design process, and design outputs. During the design input phase, requirement specifications and design specifications are written. The inclusion of any FDA-recognized consensus standard in a requirement specification is not mandatory. “Conformance with recognized consensus standards is strictly voluntary” (CDRH, 2007). Regardless of requirement origin, subsequent demonstration that requirements are met must also include sufficient evidence of medical device safety and effectiveness.

Risk analysis spans both the design input and design output phases. Initial risk analysis, during which potential device hazards are assessed, is clearly part of design input. Based on this analysis, the device design is modified to minimize the occurrence of specific hazards. However, in its guidance document, the FDA states that “the results of risk analysis” are an example of design output (CDRH, 1997b). For the purposes of design control, we consider risk analysis implementation and sign-off to be design output. These days, under ISO 14971: Medical devices – Application of risk management to medical devices (ISO, 2007), risk management is considered a continuous process which spans well beyond design inputs and design outputs.

During the design output phase, each specific requirement from the design input phase is verified. As part of the design output phase, the new medical device is validated to ensure that user needs and clinical performance requirements are met. During each phase, a design review takes place before moving to the next phase. After validation, the design is transferred to manufacturing. Device documents are maintained in a design history file. While not mandatory for design control, it is helpful to initiate the product development process with a product requirements specification, which is not under rigid document revision control. In this way, initial marketing needs are documented.

Biomaterials Design Controls Examples

In this subsection, we describe specific examples of how biomaterials are handled by design inputs and outputs. The class of the device under development predetermines the testing complexity.

ECG electrode

For an ECG electrode (Figure III.2.6.4), which is a Class II device, biomaterials specification and testing are relatively straightforward.

FIGURE III.2.6.4 Red Dot™ Foam ECG Monitoring Electrode (3M, St. Paul, MN, USA).

A manufacturer typically follows the national standard ANSI/AAMI EC12:2000/(R)2005 Disposable ECG electrodes. In this standard for ECG electrodes, electrical performance and biologic response requirements are defined (AAMI, 2005a). The biologic response requirements for cytotoxicity, sensitization, and irritation point to the national and international standard ANSI/AAMI/ISO 10993-1:2003 Biological evaluation of medical devices – Part 1: Evaluation and testing (AAMI, 2003). In the cytotoxicity tests, the lysis and growth inhibition of mouse fibroblast cells are determined, after exposure to an extract dilution of the electrode adhesive or gel. In the sensitization tests, erythema and edema of human skin are assessed after two applications of electrode adhesive or gel. In the irritation tests, erythema and edema of rabbit skin are assessed after electrode adhesive or gel application. In addition to these verification tests, the manufacturer may wish to provide validation clinical data demonstrating that human heart rates determined with the ECG electrode under test are insignificantly different from heart rates determined with a predicate ECG electrode. However, clinical data are not required for a 510(k) submission. This type of simple 510(k) submission is typically cleared by the FDA within 90 days.

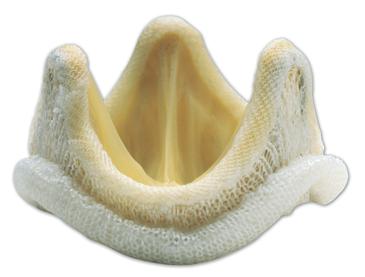

Tissue Heart Valve

For a porcine tissue heart valve, which is a Class III device, biomaterials specification and testing becomes more complicated. Indeed, to demonstrate safety and effectiveness of the Carpentier-Edwards S.A.V. Bioprosthesis Model 2650 aortic valve (Figure III.2.6.5), ISO 10993 testing, animal studies, and clinical trials were performed.

FIGURE III.2.6.5 Carpentier-Edwards S.A.V. Bioprosthesis Model 2650 Aortic Valve (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA).

This valve consists of a porcine aortic valve mounted on a flexible frame. The recovered porcine valve tissue is treated with ethanol and polysorbate-80, and packaged and terminally sterilized in glutaraldehyde.

As with the ECG electrode, cytotoxicity, sensitivity, and irritation tests were performed, using samples of materials involved in the valve manufacture. Some of these materials were silk suture thread, silicone rubber, and polyethylene terephthlate cloth and film. Additionally, other ISO 10993 tests were performed to assess genotoxicity, hemocompatibility, systemic toxicity, and implantation.

As a precursor to clinical trials, in vivo animal studies were conducted. Since these studies were conducted in the 2001 timeframe, they followed the FDA Draft Replacement Heart Valve Guidance of 1994 (CDRH, 1994). However, the animal studies are consistent with the current national and international standard ANSI/AAMI/ISO 5840:2005 Cardiovascular implants – Cardiac valve prostheses (AAMI, 2005b). Eleven juvenile sheep were implanted with the valve in the aortic or mitral position for five months. Similarly, 12 weanling rats and 12 juvenile rabbits were implanted subcutaneously with porcine aortic valve tissue for 90 days. In both studies, histopathology and calcification were assessed. In the sheep study, hemodynamic performance was also assessed.

Finally, before PMA submission in 2001, clinical trials were conducted. Again, the clinical trials followed the FDA Draft Replacement Heart Valve Guidance of 1994. These studies do not meet the current requirements of ISO 5840:2005 in terms of minimum number of enrolled patients. In one prospective study, the adverse event rates were recorded at one year for valve-related mortality, explants, reoperation, bleeding, endocarditis, hemolysis, nonstructural dysfunction, perivalvular leak, structural valve deterioration, thromboembolism, and valve thrombosis (Edwards, 2002). The time interval between premarket submission and FDA approval for this aortic tissue valve was 11 months. Eight amendments were required during the approval process (CDRH, 2002).

In the current version of ISO 5840:2005, a minimum of 150 tissue valve patients are followed for at least five years each. The complication rates for structural valve deterioration, thromboembolism, valve thrombosis, anticoagulant-related hemorrhage, endocarditis, valve dysfunction/paravalvular leak, and re-operation are recorded at one year. The complication rates for similar criteria are recorded at five years. In both cases, the observed complication rates must be within acceptable complication limits (AAMI, 2005b).

Permanent Skin Substitute

Design controls for Class III devices with which the FDA has little or no previous experience are the most difficult. As already discussed, requirements are to be determined by the manufacturer, regardless of accepted consensus standards. A device that meets these requirements must demonstrate safety and effectiveness in its FDA premarket submission. The threshold for this demonstration is made solely by the FDA.

When Advanced Tissue Sciences (ATS) submitted its request to market its Dermagraft® permanent skin substitute in December, 2000, it did not realize that 57 months would elapse before FDA approval. Dermagraft® is a cryopreserved dermal substitute composed of human fibroblasts, extracellular matrix, and a bioabsorbable scaffold (Figure III.2.6.6).

FIGURE III.2.6.6 Dermagraft® Skin Substitute (Advanced BioHealing, Westport, CT, USA).

No FDA consensus standard existed in 2000, upon which permanent skin substitute submission requirements and testing could be based. In order to obtain the Indication for Use of “treatment of full-thickness diabetic foot ulcers greater than six weeks duration,” ATS worked with the FDA on study protocols whose positive results would demonstrate safety and effectiveness. When ATS met with the FDA General and Plastic Surgery Devices Panel in January, 1998, its biocompatibility results were accepted. The cytotoxicity, irritation, systemic toxicity, genotoxcity, and stability/shipping data were deemed “adequate.” It was not stated in the Panel meeting transcript if any of these tests were based on ISO 10993 specifications.

The Panel voted 7-to-2 in favor of approval with a postmarket study, in order to resolve questions about data from two clinical trials. Specifically, only a subset of patients in the pivotal randomized clinical trial met the intent-to-treat hypothesis. While this subset was treated with grafts within a retrospectively determined narrower therapeutic range of cell viability, the therapeutic range was not statistically validated (CDRH, 1998a). After the Panel meeting, the FDA continued to raise concerns with ATS about the narrower therapeutic range issue (ATS, 1998). Moreover, the premarket approval manufacturing inspection for Dermagraft® resulted in a warning letter citing issues related to contaminants, and corrective and preventive action procedures (CDRH, 1998b). On June 10, 1998, premarket approval was denied (ATS, 1998).

ATS was required to validate this therapeutic range of cell viability with a second pivotal randomized clinical trial. In its second PMA submission, ATS demonstrated in 314 patients that 91% of Dermagraft® patients had wound closure at 12 weeks, compared to 78% of the control patients (p = 0.044). Further, it demonstrated that the ulcers of Dermagraft® patients significantly closed faster than ulcers in the control group (p = 0.040) (ATS, 2001).

Because of the extended three year delay between the Panel meeting and FDA approval in September, 2001 (CDRH, 2001), ATS accumulated more debt before shipping Dermagraft® to market. ATS filed for bankruptcy in 2002, and sold its assets to its joint venture partner Smith & Nephew. After Dermagraft® failed to gain FDA approval for an additional indication for venous leg ulcers in 2005, Smith & Nephew sold the technology to Advanced BioHealing in 2006 (Stuart, 2008).

From a general business perspective, being first-to-market is a competitive advantage for achieving the dominant market share. However, from a medical device industry perspective, being first-to-market with a Class III device means being first-to-deal with the FDA, which is an unpredictable process.

Manufacturing Controls

Manufacturing controls partner with design controls to ensure product quality and safety. These controls oversee the manufacturing process and manufacturing facilities. At the front end of the manufacture of a specific device, purchasing controls are required for evaluating suppliers. Production and process controls are required to eliminate environmental and contaminant concerns. Inspection, measuring, and test equipment must be regularly calibrated and maintained. Manufacturing processes must be validated. Procedures must be in place for receiving acceptance activities, final acceptance activities, and nonconforming products. Corrective and preventive action, complaint file handling, installation, and servicing (where appropriate) procedures are also required (CDRH, 2003b).

For a PMA submission for a Class III device, a complete description of implemented manufacturing controls is required. While a manufacturing controls description is not required for a 510(k) submission, it is assumed that manufacturing controls are in place for the Class II device under review.

Registration, Listing, and Inspection

A manufacturer must register each of its facilities annually with the FDA, and list devices that are specified or manufactured at each facility. As of the fiscal year 2008, a fee must be paid during annual registration. For fiscal year 2009, this fee is $1851.

Registration, listing, design controls, and manufacturing controls are verified during an FDA inspection. Generally, a manufacturer is notified one week before the inspection occurs.

An initial inspection of a manufacturer’s facility is conducted before its first product is market released. For Class III devices only, an inspection is generally conducted during the PMA submission process. (This is the inspection for which ATS received a warning letter.) However, if two PMAs are being reviewed during the same year period for a mature company, a second inspection may not occur. For both Class III and Class II devices, an inspector also returns to review a device recall, correction, removal or reported medical device complication. An inspector may also visit to follow up on observations from a previous inspection, which had been documented in a Form 483 warning letter.

Intellectual Property

While a few companies still patent all their new technologies, these days it is more cost effective to patent only technologies that create a barrier to market entry for competitors. A US patent can easily cost $25,000 to $30,000 from initial filing to issue. This cost includes attorney fees and US Patent Office (USPTO) fees. For the fiscal year 2009, the basic USPTO fees for filing a utility application, assuming at most 20 claims, total $1310. If other countries are chosen for protection, then the cost for issued patents escalates exponentially.

Three types of US patents exist: design; plant; and utility patents. A design patent protects the look or ornamentation of an article of manufacture. A plant patent protects the discovery and asexual reproduction of any distinct and new variety of plant. A utility patent protects a process, machine, article of manufacture or composition of matter.

In order for an invention to be protected as a utility patent, it must be utile, novel, and not obvious. Utility is not a high threshold to cross. An invention may be broadly interpreted to be useful, as long as it is not a law of nature or abstract idea. For an invention to be novel, it cannot be known or used by others anywhere in the world, more than one year before the inventor files his/her US patent application. Therefore, any previous public disclosure of the invention by another person, such as in an obscure foreign abstract or in an abandoned US patent, acts as prior art. If the inventor has publicly disclosed the invention, they must file for a US patent within one year of disclosure. Any similar prior art must not be obvious. In other words, a person having ordinary skill in the art of the invention must not consider the invention to be apparent. An example of obviousness would be the combination of two previous inventions.

The patent attorney representing the inventor writes broad claims for the invention, and negotiates with USPTO for allowance of these claims. For an issued patent, the invention is generally protected for 20 years from the date of US filing.

An issued patent does not guarantee that another company will not infringe on the patented invention. When this occurs, the company of the inventor is often forced to sue for infringement of specific patent claims. In anticipation of defending patent claims in the future, an inventor provides a written description, enabling disclosure, and best mode of the invention in the patent specification (the patent application text that excludes the claims) at the time of patent filing. The enabling disclosure refers to the requirement that a person having ordinary skill in the art of the invention would be taught by the patent how to make the invention. The best mode refers the best design of the invention being claimed at the time the patent application was filed. When an infringement lawsuit goes to trial in a US District Court, a jury decides the case. Either party may appeal the decision to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

The Cypher® Stent US Patents

In 2005, in the US District Court of Delaware, Johnson and Johnson’s Cordis’s Cypher® stent (Figure III.2.6.1) was found to infringe on Boston Scientific’s drug-eluting stent patent US 6,120,536. Claim 1 in patent ‘536 describes a drug-eluting stent with a coating containing a non-thrombogenic surface. Cordis appealed to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, stating that the Boston Scientific claim was obvious, in light of similar claims from Medtronic patent 5,545,208 (Figure III.2.6.7). In January, 2009, the Court of Appeals reversed the original judgment: “because the court erred as a matter of law in failing to hold the ‘536 patent to have been obvious” (United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, 2009).

FIGURE III.2.6.7 An illustration of the stent covered by Medtronic’s US patent 5,545,208.

Developing a medical device with key biomaterial components for the US market is not for the faint of heart. Especially with these devices, it becomes an art to navigate the regulatory roads towards FDA approval and Medicare reimbursement. In this chapter, we have discussed issues which are important for releasing a device to the US market: regulatory strategy; Medicare reimbursement; design controls; manufacturing controls; registration, listing, and inspection; and intellectual property. We leave it to others to discuss these changes and issues for market released products, such as US postmarket surveillance, medical device reports, corrective action and preventative action, and recalls (Baura, 2012). As this chapter goes to press in 2012, the FDA is considering major changes to the regulatory process.

Further Reading

For more detailed information on medical devices and US medical device regulation, please see:

2. Baura GD. System Theory and Practical Applications of Biomedical Signals. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-IEEE Press; 2002.

3. Baura GD. A Biosystems Approach to Industrial Patient Monitoring and Diagnostic Devices. San Rafael, CA: Morgan Claypool; 2008.

4. Baura GD. Medical Device Technologies: A Systems Based Overview Using Engineering Standards. Waltham, MA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2011.

5. Baura GD. US Medical Device Regulation: An Introduction to Biomedical Product Development, Market Release, and Postmarket Surveillance. Manuscript in preparation 2013.

Bibliography

1. AAMI. ANSI/AAMI/ISO 10993-1:2003 Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices – Part 1: Evaluation and Testing. 2003.

2. AAMI. ANSI/AAMI EC12:2000/(R)2005 Disposable ECG Electrodes. 2005a; Arlington, VA.

3. AAMI. ANSI/AAMI/ISO 5840:2005 Cardiovascular Implants – Cardiac Valve Prostheses. 2005b.

4. ATS. June 11 Press Release: FDA Responds to Premarket Approval Application. 1998; San Diego, CA.

5. ATS. Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data: Dermagraft, P000036 Rockville, FDA. 2001.

6. Baura GD. US Medical Device Regulation: An Introduction to Biomedical Product Development, Market Release, and Postmarket Surveillance. Manuscript in preparation 2013.

7. CDRH. Draft Replacement Heart Valve Guidance. 1994; Rockville, FDA.

8. CDRH. Approval Order P940001. 1997a; Rockville, FDA.

9. CDRH. Design Control Guidance for Medical Device Manufacturers. 1997b; Rockville, FDA.

10. CDRH. General and Plastic Surgery Devices Panel Transcript: January 29, 1998. 1998; Rockville, FDA.

11. CDRH. Advanced Tissue Sciences Warning Letter WL-21-8. 1998a; Rockville, FDA.

12. CDRH. Approval Order P000036. 2001; Rockville, FDA.

13. CDRH. Approval Order P010041. 2002; Rockville, FDA.

14. CDRH. Approval Order P020026. 2003a; Rockville, FDA.

15. CDRH. Quality System Information for Certain Premarket Application Reviews: Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff. Rockville, FDA 2003b.

16. CDRH. Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Recognition and Use of Consensus Standards. 2007; Rockville, FDA.

17. CMS. Medicare Program; Changes to the Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems and Fiscal Year 2003 Rates. Final Rule, August 1, 2002 2002; Washington, DC, US Federal Register.

18. CMS. Medicare Program; Changes to the Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems and Fiscal Year 2003 Rates; Proposed Rule, May 9, 2002. Washington, DC: US Federal Register; 2002.

19. CMS. Medicare National Coverage Process. Washington, DC, HHS 2009.

20. Cordis. Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data: Cypher Sirolimus-eluting coronary stent: P020026. 2003; Rockville, FDA.

21. Edwards. Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data: Carpentier-Edwards S.A.V Bioprothesis, Model 2650 (Aortic), P010041. 2002; Rockville, FDA.

22. ISO. ISO 14971:2007 Medical Devices – Application of Risk Management to Medical Devices. 2007; Geneva.

23. OCP. Request For Designation RFD 0.006. Rockville, FDA 2000.

24. ODE. Annual Report Fiscal Year 2006 and Fiscal Year 2007. Rockville, FDA 2008.

25. Stuart M. The Rebirth of Dermagraft Start-up, 13. 2008.

26. United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Boston Scientific Scimed, Inc and Boston Scientific Corporation v. Cordis Corporation and Johnson & Johnson, Inc 2009; 2008–1073.

27. Wolff RG, Hull VW. Intralumenal Drug Eluting Prosthesis. 1996; U.S. 5,545,208.