The more you learn about Elva Statler, the more hauntingly elusive the young woman remains. Just when you think you’ve pictured her face, she slips through your fingers like an evocative melody that you’ve become obsessed with but suddenly can’t hum. Even her name, which could be mistaken for a feminine version of Elvis, is ambiguous. One source says Elva is a variant on the name Olivia. Another says it comes from the Anglo-Saxon for “elf.”

There are a number of photos of Elva from various sources. Oddly, though, each one looks like a different girl. You go through them repeatedly and place them side by side and search in vain for a common thread, like face-recognition software failing to make a match. It isn’t the Three Faces of Eve being examined here, but the Many Faces of Elva.

It is even hard to tell for sure whether she was pretty. Several reporters referred to her as “the pretty heiress,” and one went so far as to call her “the beautiful heiress.” But you get the idea that they were merely engaging in cookie-cutter journalese straight out of a Dashiell Hammett novel or L.A. Confidential. After all, none of those reporters ever saw her in person. Neither did former Tufts archivist Khris Januzik, but from the pictures she declared Elva to be “not pudgy, just healthy-looking by the standards of her day—not outrageously gorgeous, but pretty.”

Though the late Mary Evelyn de Nissoff never became friends with Elva, who was ten years older, she did know her as a child. Mary Evelyn said not long before her death:

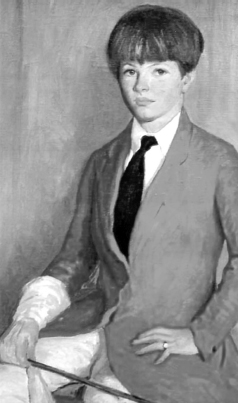

This portrait shows Elva as a youthful horsewoman. Courtesy of Andrew Edmond.

She was quite athletic. She played golf and played tennis and rode horses. She did not have a pretty face. I would say she was more sharp-featured or pinched, although in one or two pictures, she looks quite attractive. She was kind of innocent-looking. Dirty blonde, I would say. And everybody said she was “pigeon-breasted,” whatever that meant. I think it meant there was a bone in there that stuck out or something. She wasn’t really that attractive…As for her personality, all I remember is that she just seemed lost.

In one likeness, a copy of a three-quarters sketch by The New York Times artist Tom McCoy, Elva appears positively glamorous. Looking as if she’s going out for the night, she has her hair in a fashionable crimp and wears elegant pearl earrings. Since it’s a drawing instead of a photo, it was no doubt unrealistically flattering. But there’s something compelling in the vulnerable, accusatory stare of her eyes and the slight pout on her small, Clara Bow mouth, as if she’s somehow demanding honesty of the viewer.

A couple of papers printed a photograph of Elva that is so similar to the sketch that The Times artist must have based his work on it. The angle and the expression are the same, though in the photos she looks a little rougher around the edges. Pretty? Hard to say.

Another picture, a high-quality photocopy of a sepia-toned, soft-focused snapshot, shows a younger Elva, perhaps in her late high school or early college years. But there is more than just a time difference between this face and the almost delicate, somewhat more mature one with the pearl earrings. Here she is athletic-looking, with a powerful neck and shoulders from all that swimming. She appears to be wearing an open-necked blouse and some kind of jumper. She’s unsmiling here, too, and her hair is severely parted, combed back and tucked behind her ears, as if she might have let it dry that way after coming out of the pool. Kind of a female jock. Not the same girl.

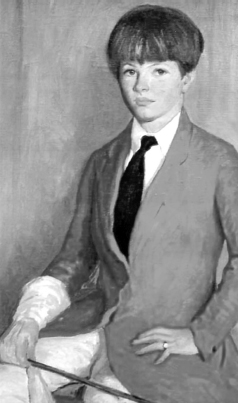

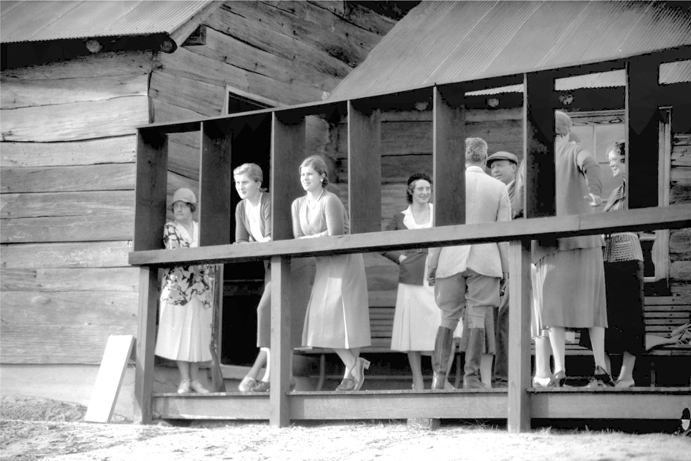

Elva Statler (third from left) and her close friend, Isabelle Stone Baer (second from left), enjoy a day at the Pinehurst Gun Club, probably in 1932. Courtesy of the Tufts Archives, Pinehurst.

Elva (right) and an unidentified woman hold live turkeys after winning a turkey shoot at the Pinehurst Gun Club. Courtesy of the Tufts Archives, Pinehurst.

In some photos, she looks just a bit boyish. In others, quite feminine. (The Washington Herald described her as “buxom.”) In some pictures, she appears warm and gracious. In others, distant, pensive and uncomfortable. In one, she looks like a typical happy teenager hanging out with her dog. In another, which shows her coming out the front door of her new brother-in-law’s house after her Pinehurst wedding, she’s wearing an ungainly gown and an unfortunate white cap and looking up at Brad with a moon-faced, worshipful expression that can only be described as embarrassingly goofy.

It is hard to escape the suspicion that the Many Faces of Elva are at least partly a reflection of what must have been a troubled personality—a lost soul who didn’t know who she was and spent her short, unhappy time on earth in an unsuccessful search for herself. If she went from version to version of her own identity, it shouldn’t be surprising that she looked different every time one saw her or snapped her picture.

Regrettably, there is virtually nothing in her voice. One wouldn’t expect a recording—just something she might have said or written, something in her own phraseology that might open a door onto her personality. Other than a few snatches from letters and telegrams to the man who was so fleetingly her husband, and her supposed last words, “Goodnight, darling”—themselves of uncertain authenticity—little seems to remain but impenetrable silence.

Whether the leading lady of our story really said “Nobody likes me” or “Nobody loves me” on the night before her death, she obviously had plenty of reasons—even on the surface of things—to feel unloved and abandoned. But it went even deeper than that. Despite her many advantages, it is all too touchingly clear that she felt like a nobody herself.

That would have seemed strange to the millions of down-and-outers standing in urban soup lines during those turbulent thirties, out of money and out of hope. She was a member of the wealthy, self-indulgent stratum of that era, which became the closest thing to a nobility or a ruling class that America had produced at least since the robber barons of the late nineteenth century. They wielded much power and indulged many extravagant whims in those unregulated days. The papers were full of their exploits and scandals, which entertained the restless masses trying to make ends meet. Elva was a member of that aristocracy. To the suffering commoners looking enviously across the social void, that would have made her Somebody. But to herself, at some profound psychological level, she was poorer and more deprived than they.

Elva Statler plays golf at Pinehurst in 1932.Courtesy of the Tufts Archives, Pinehurst.

“Be kind to her,” Elva’s great-grandnephew, Andrew Edmonds, said when interviewed for this book. “Elva wasn’t perfect, but her life was so tragic.” And so it was. She started out her sojourn on earth by being found in the bullrushes and placed among strangers, with no idea about her real parents or her real station in life. Then, at an age at which most sheltered American children have never experienced a single death in the family, she had already watched almost all those near and dear to her die agonizingly, one by one. She had two remarkable skills, as a pianist and as a swimmer, and showed promise of great accomplishment in either or both. But illness deprived her of one and injury of the other. Before she had even reached her twenty-first birthday and entered adult life, she was already a walking disaster area.

Elva and many of the other principal characters in the Davidson cast appear in articles published from 1928 through 1935 in The Outlook, Pinehurst’s social register and propaganda organ.

Miss Isabelle Baer paid a visit to Miss Elva Statler prior to Miss Statler’s marriage to Mr. H. Bradley Davidson. Mesdames H. Bradley Davidson and Herbert Vail served as patronesses of the Black and White Ball. Mr. H. Bradley Davidson dressed as a sailor at a Valentine’s Day masquerade (when Mrs. H. Bradley Davidson was out of town). Dr. M.W. Marr, Pinehurst’s resident physician, dressed up as a doctor treating five ladies dressed in baby clothes as the Dionne quintuplets, who were all the rage at the time.

“Special Parties Accommodated,” Montesanti’s Spaghetti Camp advertised. Mrs. Betty Hanna Davidson (continually overspending her allowance from her wealthy Ohio family after marrying Richard) had gone into business, setting up an Elizabeth Arden salon. That same Mrs. Davidson sponsored a dance during the Mid-South Golf Tournament, giving the affluent snowbirds an opportunity to benefit the undernourished indigenous children of Moore County.

This formal portrait is of Elva’s best friend, Isabelle Stone Baer.

Miss Elva Statler of New York, wearing an elegant gown, and dashing young Mr. Jack Rudel of Montreal, resplendent in a tux, won a New Year’s Eve scavenger hunt. Among the items they had assembled in less than an hour were a crusty old bachelor, a finicky old maid, the U.S. Constitution, a last year’s bird nest, a Massachusetts license plate, a hand of tobacco, a useless Christmas present, something incongruous and a deck of cards minus the ace of spades.

Then there is that splashy layout that appeared on January 5, 1935, under the headline “A Pinehurst Wedding of Great Interest,” detailing “the marriage of Miss Elva Idesta Statler and Mr. H. Bradley Davidson Jr. on Thursday noon at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Richard P. Davidson in Knollwood.”

The story takes up more than a page. Accompanying it is a photo of the newlyweds grinning as they examine a piece of paper, perhaps a scorecard, on some kind of sporting field. He towers a head and a half over her. Both of them are dressed in stylish layers against the cold, and both are looking about as good as they could look. They seem happy, and they seem like a couple.

“The bride was escorted to the altar by Mr. Richard P. Davidson and was given in marriage by her sister-in-law, Mrs. Milton Howland Statler of Tucson, Ariz., who was matron of honor,” the paper reported. “Mr. Nat S. Hurd of Pinehurst was best man. The ceremony was performed by the Rev. Dr. Murray S. Howland, of Binghamton, N.Y.”

The Davidsons married in January 1935 at the Pinehurst home of Richard Porter, Brad’s younger brother. From left: Richard Porter; Mrs. Nat Hurd, Elva’s next-door neighbor; Brad; Elva; Nat Hurd; and Betty Hanna Davidson, Richard’s wife. Courtesy of Andrew Edmond.

Elva beams on her wedding day. Courtesy of Andrew Edmond.

The improvised altar, the article says, was decorated with madonna lilies and lilies of the valley, and the house was decorated with white lilies, lilies of the valley and white snapdragons. Elva had even brought in a string quartet from the North Carolina State Symphony, founded only a couple of years before, to play the Lohengrin wedding march.

“The bride wore a white satin wedding dress with an Elizabethan collar,” the article says. “Her cap was of white net with a collar of orange blossoms. She carried white orchids. The matron of honor wore a blue taffeta dress made in Empire style, with pleated ruffles, and a blue hat to match. She carried yellow roses. Miss Statler’s going-away costume was a gray tailored suit with hat to match, and a topcoat of gray caracul.”

The new Mrs. Davidson was “graduated [not exactly] from Radcliffe College in 1934,” the paper said. “She has been to Pinehurst many times with her family and this winter for the first time joined the cottage colony, leasing the ‘Edgewood’ cottage on Linden Road. She is known at Pinehurst as an expert horsewoman and has won many prizes here.”

The rest of the article devotes itself to a detailed account of the many parties held during that “active and gay” week and who attended them, providing a veritable who’s who of Brad and Elva’s friends. Brother Richard and his wife had a dinner for the couple. A Miss Helen Louis Heim gave a tea for the bride. Mr. and Mrs. Richard Tufts of the Pinehurst ruling family gave a buffet supper for the groom’s mother. The night before the wedding, while Elva entertained the womenfolk in her house, Brad threw his stag dinner at—where else?—Montesanti’s Spaghetti Camp.

Mary Evelyn de Nissoff had a more blunt and jaded version of what Pinehurst life was really like in the 1930s. It provided a helpful counterpoint to all that high-society gloss in The Outlook. “The fact is that this gang put Elva together with Brad because he needed a rich woman and they wanted to get her married off,” she said. “There used to be men like that, who came from good families that had lost their money, and they used to do the resort scene here and in Europe. Because this is where the rich women went—usually older women—who were willing to support these gigolos.”

What struck Khris Januzik, the former Tufts Archives lady, was the ironic contrast between the extravagant, scorched-earth coverage The Outlook devoted to Elva’s wedding and the terse, one-paragraph squib it gave to her death a few short weeks later—at a time when papers from coast to coast were printing front-page stories with all the juicy details their reporters could beg, borrow or steal. Clearly this was not a newspaper; it was a spin sheet.

“All The Outlook has about her death is just this tiny little thing regretting her passing,” Khris said. “Just shortly before, there’s the big write-up of her wedding, and you look at the guest list and everything and realize that she was right up there with the Tuftses and everybody on the upper echelon of the social circles here at the time. And then there’s this little, ‘Gee. We’re sorry she’s gone.’ Now, wait a minute, okay? Queen Victoria got more ink than that when she died, and they didn’t even know her!”

One of the last known photographs of Elva Statler shows her in a fashion show at Pinehurst in 1935.Courtesy of the Tufts Archives, Pinehurst.