ALWAYS THINK CONSCIOUSLY OF THE FACT THAT THE STRENGTH FOR EVERY TECHNIQUE COMES FROM THE HARA.

—A. PFLUGER, KARATE BASIC PRINCIPLES

Principles

Fighters’ midsections must to do five things well.

1. Act as body armor.

2. Transfer the power between the lower and the upper body without energy losses and with good spine mechanics.

3. Maintain proper breathing behind braced abs for the duration of the fight (Yin breathing).

4. Explosively compress the breath and to stiffen up the body on impact (Yang breathing).

5. Provide reflexive rotary stability.

The first item is the most obvious one. Hypertrophy of the abdominal wall is in order. Up the number of sets of Hardstyle sit-ups and hanging leg raises to thicken the six-pack. Chad Waterbury, strength coach for Ralek Gracie and director of strength and conditioning for the Rickson Gracie International Jiu-Jitsu Academy, comments:

When it comes to training fighters, using nothing but planks and similar exercises that focus on developing core tension while maintaining a neutral spine isn’t optimal. Your nervous system always knows the best way to protect yourself—that’s its job. If someone throws a front kick toward your gut, the reflex action is to pull the ribcage down to develop maximal tension in the abdominals. The high-tension reaction serves to protect your organs like a plate of armor. This reflex action is hardwired into your nervous system, much like the hip flexion withdrawal when you step on a tack. No one lifts his chest or pushes his stomach out when a strike is coming towards his midsection because the nervous system knows better. For abdominal tension to reach its peak, drawing the ribcage down toward the pelvis is necessary and this is accompanied by some degree of spinal flexion. Full spinal flexion should never be the goal when training the core, or any other exercise, since it’s almost always best to maintain lordosis. However, a fighter must develop his ability to quickly induce high levels of abdominal tension in order to withstand strikes to the midsection, and this requires the amount of spinal flexion necessary to pull his ribcage down. Any spinal flexion beyond what it takes to pull your ribcage down is unnecessary and high-risk to your spine.

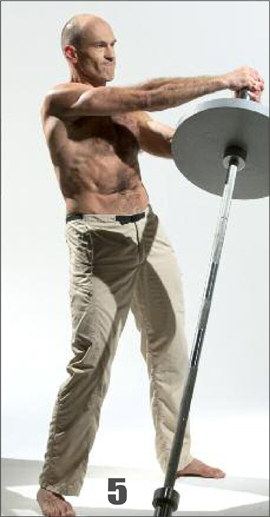

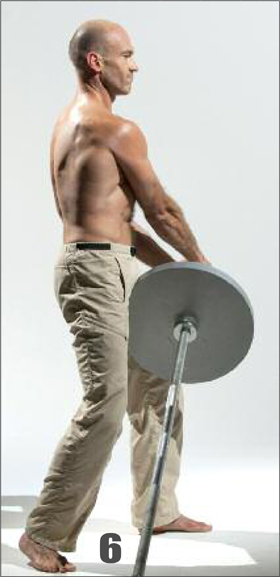

The sides are effectively built up with full contact twists, suitcase deadlifts, and various Zercher lifts. Hanging leg raises will go a long way as well.

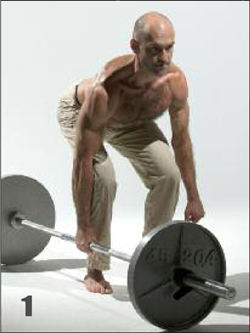

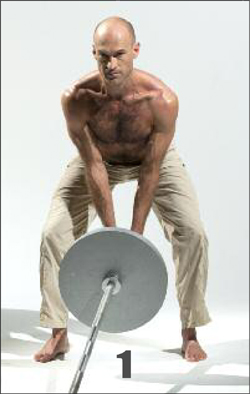

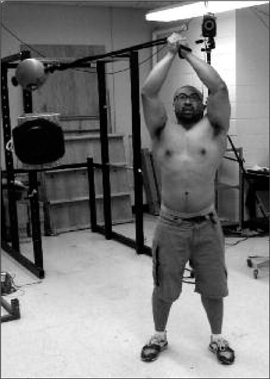

The suitcase deadlift.

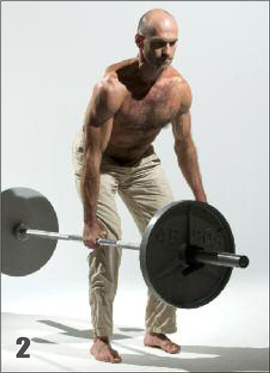

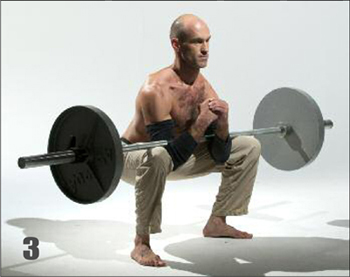

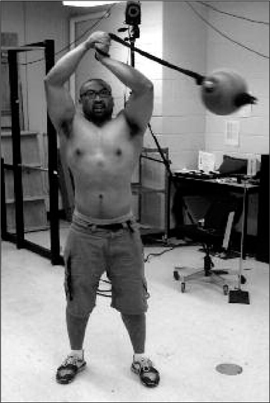

The Zercher squat.

For the second item the drill of choice is the full contact twist, which I will describe in a minute. As a thrower, a fighter ought to do low sets of low reps, e.g. 3-5x3-5, not the typical high rep nonsense (we will discuss building muscular endurance the right way in #3). In the immortal words of elite MMA strength coach Steve Baccari, RKC, “Before working on strength endurance you need to have some strength to endure.”

Norwegian scientists conducted two studies, one on long distance runners58 and the other on cyclists59. These experienced endurance athletes were put on a pure strength program, 4x4RM half-squats three times a week, in addition to their usual endurance training. Eight weeks later the athletes not only got stronger and more explosive—without gaining any weight!—they improved endurance in their sport: their movement efficiency improved and the time they could last to exhaustion at maximal aerobic power increased.

On the energy systems continuum—alactacid, lactacid, aerobic—throwers are on one extreme end of the spectrum, with long distance runners and bicyclists are on the other, and fighters in the middle. Would it not be logical that if low rep pure strength training helped pure endurance athletes, it would help you even more? As a bonus, such training is non-exhaustive and, as you have seen, it does not increase one’s bodyweight.

How does it work?—The stronger the muscle, the less it has to contract to produce a given amount of force.60 It may be obvious, but it is profound. In the above studies the athletes increased their movement economy and decreased their perceived effort. How does our body perceive effort?

The nervous system measures the intensity of the neural drive going to the muscles.61 The muscles send back messages about the level of tension generated, the speed of movement, and the distance covered. The brain compares the intensity of the “nerve force” with the outcome and determines the degree of effort.62 In other words, how much bang (mechanical work) do you get for the buck (the intensity of the “nerve force”). A weight may “feel” heavy not because it is heavy but because it takes a lot of “juice” to move it.

“The size of the neural drive required to generate a given external force is influenced by a number of factors, but principally by the force-generating capacity of the muscle. A strong muscle requires a lower neural drive to generate a given force, because the force represents a smaller proportion of its maximum capacity. Similarly, a fatigued muscle requires a higher neural drive to generate a given force, because the force represents a higher proportion of its maximum capacity.”63

Which is why a strong fighter who is skilled enough at relaxation can go the distance: he is barely trying and still putting out a heck of a power. This applies to all your muscles, with those of the midsection being a special case.

Storage of elastic energy in a compliant spring, or a soft spring is rapidly dissipated or lost. This happens if the muscle is not activated to a sufficient level. If the spring is too stiff, elastic energy storage is hampered because there is minimal elasticity and no movement… So, the pre-contraction level of the muscle just prior to the loading phase is extremely important… a lot of stiffness and stability is achieved in the first 25% of the maximum contraction level. From our work examining several different rapid loading situations, it appears that a pre-contraction level of about 25% MVC [maximal voluntary contraction] creates the amount of muscle stiffness for optimal storage and recovery of elastic energy in the core muscles (at least in many situations). Less than this results in a spongy system while more than this creates stiffness that impedes energy return and also unnecessarily crushes the spine and the joints.

It is a fact that tensing the midsection spreads tension all over the body—the phenomenon of irradiation I have written about in Power to the People! Which is great at the moment of the strike’s impact but decidedly bad in flight. Russian full contact karate master and Spetsnaz vet Andrey Kochergin explains that rigidity is often the result of trying to lead the limb along its trajectory instead of letting it fly. He stresses: “Throw [the limb], then make an accent [kime] when it has arrived.” One of his recommendations is relaxation training—“throw relaxed arms in different ways and in all directions and shake them until ‘meat separates from the bones’”—but he also does heavy powerlifting training.

Only a strong person is able to stay truly relaxed when striking. If your abbies are weak, two equally unpleasant scenarios will play out.

One, you have managed to stay relaxed, in which case your soft underbelly will absorb a good part of your leg drive instead of passing it on to the shoulder (“You can’t push a rope”, famously quipped McGill). That means a weak strike.

Or two, you have stiffened your core enough—but it took so much effort that the tension has overflowed to your limbs. The punch is no longer a punch but a push, slow and tiring.

Having killer abs strengthened with low rep work will allow you to keep your torso stiffened just the right amount without even trying. Your limbs will stay relaxed, you will be powerful and not tired.

Now that I have hopefully convinced you to go heavy and do low reps, here is the drill.

The best exercise for transferring the hip power into the shoulder with a high interest is the full contact Twist. This exercise was originally developed in the Soviet Union for throwers. The then nameless twist came to fighters’ attention when a famous Russian shot putter failed to talk his way out of a mugging. This mild mannered man got annoyed when one of the attackers cut him with a blade and he ruptured the punk’s spleen with a single punch. Soviet justice’s modus operandi could have been “Not a single good deed will go unpunished.” But this time the innocent man defending his life got acquitted of manslaughter. The story made the papers.

One of the Comrades who read it was Igor Sukhotsky, formerly a nationally ranked weightlifter and an eccentric sports scientist who took up full contact Kyokushinkai karate at the age of forty-five. This renaissance man researched shot putters’ training and noticed that the twist had not only increased his striking power, but also had toughened his midsection against blows. Sukhotsky was so impressed with the full contact twist that he added it to his super abbreviated strength training routine that consisted of only four exercises, the three powerlifts plus good mornings. It was Sukhotsky who popularized this drill among Russian fighters.

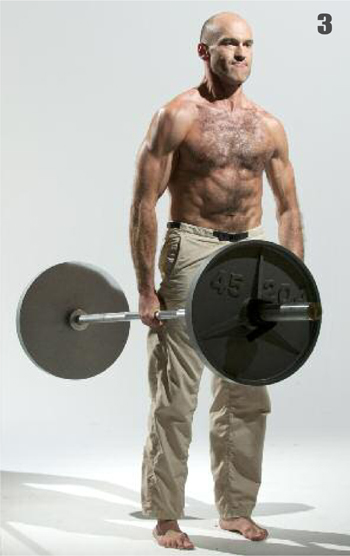

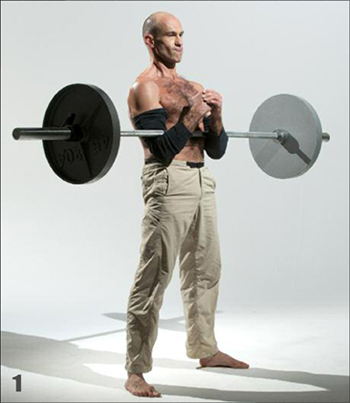

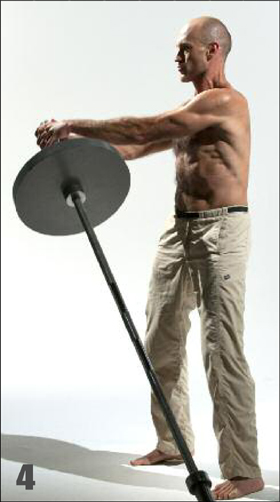

Load a barbell on one side. A hundred pound plate on the end of the bar is a reasonable goal for a serious athlete, but be sensible and start with a Barbie plate or an empty bar. Stick the other end in the corner. Protect the wall with a folded towel.

Pick up the loaded end of the bar and hold it in front of you with your fingers interlocked. The bar should be at approximately 45 degrees from the floor, although you may have to adjust the angle to suit your height and leverage.

Pick up the loaded end of the bar and hold it in front of you with your fingers interlocked. The bar should be at approximately 45 degrees from the floor, although you may have to adjust the angle to suit your height and leverage.

Setting up for the FCT.

Maintain a neutral spine for the duration of the set: avoid flexion, extension, or rotation.

Keep your arms straight and your knees slightly bent. If you have a hard time keeping your elbows locked, concentrate on flexing your triceps. It helps if you are a pistol shooter: the push-pull action of the straight arms is identical.

Remaining upright, inhale and turn the weight to one side while holding your breath. Don’t lean with the bar, or away from the bar.

Pivot on your toes at the same time to avoid shearing forces on your knees. Make sure to wear shoes that do not catch on the surface where you are exercising. Even better, train barefoot.

Reverse the movement by tightening up your midsection and rotating your hips. Do not lift with your arms and shoulders. Do not exhale until you reach the top of the lift.

Control the weight at all times, don’t use momentum.

Repeat the exercise in the opposite direction. That was one rep. You will need to readjust your stance slightly—you will figure out how when the weight gets heavy enough—when switching directions.

Now for the finer points. Do not lift the bar with your arms and shoulders. Initiate the twist with the ball of your right foot, then tense your right inner thigh. Contract your right glute and turn your hips to the left. Continue to your obliques and abs, compress your ribs, tense your lats, and only then move your rigid arms.

Let us go over the power chain one more time: the ball of the foot -> the inner thigh -> the glute -> the trunk -> the lats -> the arms -> the barbell.

This is a good time to state that in this “rotational” exercise there is no spine rotation: the ribcage is glued to the pelvis. When we tested the full contact twist at McGill’s lab the professor was pleased to see that there was no spinal rotation involved. Something is twisting but that “something” is not the spine. McGill sums up: “The core, more often than not, functions to prevent motion rather than initiating it. Good technique in most sporting, and daily living tasks demands that power be generated at the hips and transmitted through a stiffened core.”

3. Maintain proper breathing behind braced abs for the duration of the fight (Yin breathing).

This refers to not sucking wind and breathing with one’s diaphragm when maintaining a brace or when the rib cage is restricted in ground fighting.

Sticking with traditional Asian terminology—“Ignoring the fundamentals of traditional karate is the gravest mistake”—Kancho Kochergin classifies martial breathing into “Yin breathing” and “Yang breathing”. The former is used during wrestling, grappling, footwork, and some blocks. It is steady, even breathing punctuated by forced diaphragmatic exhalations during exertions: “breathing behind the shield”. Wrestlers and grapplers, accustomed to long isometric contractions and restricted postures, have the advantage over strikers. It must be noted that Oriental martial arts have very sophisticated and effective variations of such breathing and a serious fighter owes it to himself to investigate them. And make sure to read the Let Every Breath... Secrets of the Russian Breath Masters book by Systema master Vladimir Vasiliev.

Prof. McGill comments on “Yin breathing”: “An important feature of stable and functional backs is the ability to co-contract the abdominal wall independently of any lung ventilation patterns. Good spine stabilizers maintain the critical symmetric muscle stiffness during any combination of torque demand and breathing patterns… Training a breathing pattern to an exertion cycle may not be helpful.”

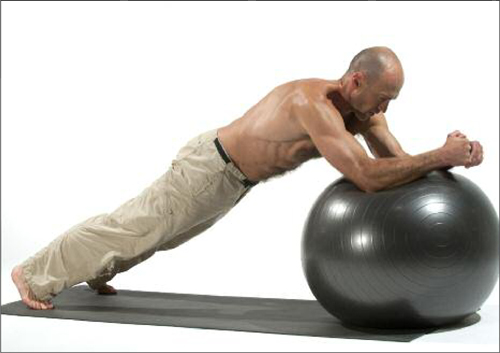

The good professor, who unlike most of his colleagues, does not bother with “untrained college subjects” and prefers applying electrodes to great athletes like George St. Pierre, has developed an outstanding exercise to develop brace endurance and Yin breathing for fighters. He calls it “stir the pot”. You will get to “integrate the entire anterior chain with torsional control”.

Assume the front plank position with your forearms on an exercise ball. Look between your forearms, at the ball. Maintaining a neutral spine and steady breathing and not allowing the pelvis to move relative to the ribcage, start drawing progressively larger circles with your elbows. “Discipline is required for minimal spine motion but maximal shoulder motion,” warns the scientist.

“Stirring the pot”.

Stuart McGill recommends starting with multiple low rep sets and progressively building up to the duration of the fight, e.g. 5min followed by 1min of rest for MMA or multiple 2min rounds for kickboxing. He stresses that “the magic happens with maintaining breathing—diaphragm contraction/relaxation within the maintenance of the armor.”

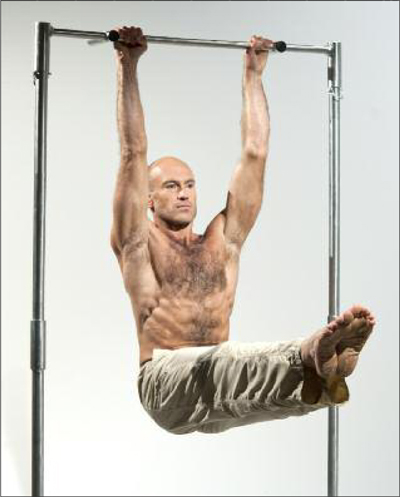

Another exercise worth considering, if it does not bother your back and your hamstrings are as flexible as they ought to be, is the L-seat hang on a pullup bar for time. As this is a “Yin exercise”, don’t use high tension techniques like gripping the bar, engaging the lats, or Hardstyle breathing. Breathe deep with your diaphragm and stay as relaxed as possible—without bending or dropping your legs or arching your lower back. The goal, according to Ivan Ivanov, formerly one of the coaches for the Bulgarian national gymnastics team, is 1min. Since this may not be long enough for a fighter and since I highly doubt that you will last even half that long, go straight to the “stir the pot” or the plank. Speaking of the latter, the goal Ivanov sets for the plank (tested when you are fresh) is 3min. (This is not the Yang plank with maximal tension for 10-20sec that we teach at the RKC course to develop tension for low rep strength exercises. This is the Yin plank where all the muscles contract at the same ratio but less intensely and the breathing is deep.)

The Yin L-seat.

Russian full contact karate fighters do the following exercise to toughen up the body while practicing Yin breathing. Lie on your back, stretch your arms and legs out like a diver. Your sparring partner steps on you, while a third person holds his hand for balance. You start slowly rolling on the floor around the axis formed by your spine. At the same time your sparring partner is walking over your body with small steps. “A very hard exercise toughening the midsection and the torso muscles,” promises Andrey Kochergin.

4. Explosively compress the breath and to stiffen up the body on impact (Yang breathing).

“Yang breathing” is breathing during a strike or some other explosive action. Unlike its Yin counterpart, it is synchronized with the movement, you “match your breath with the force”. “A sharp exhalation is performed with maximal tension and ideally, for greater concentration, with a scream,” comments Kochergin. “In the end of a Yang exhalation there is a breath hold, essential for instant concentration of a strike but counterproductive in long strength efforts of wrestling.”

The following unique and simple exercise recommended by the authoritative Russian Boxing Yearbook will help you sharpen your Yang breathing while strengthening your punch—by developing a stronger and better timed fist and building forearm muscles. The author promises that this drill will work your muscles no less intensely than a barbell works a weightlifter’s.

Get a large eraser or a rectangular block of rubber that comfortably fits into your fist, e.g. 1×1.5”×3”. Carry it with you all day and squeeze it explosively. Initiate each gripping action from your hara—compress! Be maximally explosive—imagine that you are punching. Russian special operations hand-to-hand combat instructor V. Bykov has a helpful imagery: “Move and strike as if a grenade blew up inside you”.

Get a large eraser or a rectangular block of rubber that comfortably fits into your fist. Carry it with you all day and squeeze it explosively.

“A sharp exhalation is performed with maximal tension and ideally, for greater concentration, with a scream,” comments Kochergin.

Then relax just as quickly as you have flexed! An expression by a famous Soviet expert on autogenic training Dr. Vladimir Levi comes to mind: “a mentally relaxed fist”. (I wonder if Levi had heard the Zen koan: “Where does the fist disappear to when I open my hand?”). I strongly urge you to watch my DVD Fast & Loose to improve your relaxation skills.

Eventually you will be capable of a rapid-fire, tight-loose-tight sequence—just like good punching. Just don’t pick up the pace if you still have residual tension between reps! Alternate the hands and practice for a few hours a day, which is not as difficult as it sounds because you can carry the eraser with you anywhere you go.

Fast & Loose www.dragondoor.com/dv021

The following passage from the “Karate Way” column in Black Belt by Dave Lowry will set you a distant goal to shoot for in this exercise, in your punches, and in your kettlebell swing:

Imagine a video of your reverse punch that’s broken down into 10 frames. At what point do you begin to tighten the muscles you want to be firm so you make good, solid contact? A new student starts tightening as soon as the movement begins. He’s self-conscious about the motion. He’s trying to remember technical details. He’s using all sorts of energy by squeezing his muscles long before his fist reaches the target. A more advanced practitioner, in contrast, stays loose and relaxed until frame No. 7 or No. 8. At higher levels, the tensing takes place at frame No. 10, the last moment. From there, more mastery comes when you don’t tense at the beginning of No. 10 but at the last part of it.

The karateka calls this ability “turning laziness into technical mastery”. Note that this kind of “laziness” does not refer to slowing down or weakening the contraction but to limiting its duration, a very important Hardstyle distinction.

Some martial arts styles practice a very powerful Yang breathing technique called “reverse breathing”. It calls for expanding the abdomen, especially the sides, when explosively exhaling and striking. Teaching it is beyond the scope of this book but various Zercher exercises will help you develop it.

Another excellent exercise to develop kime is the bottom-up kettlebell clean. Once you are proficient in the basic swing, place a light kettlebell slightly in front of you, its handle turned ninety degrees from what you are used to. Grip it exactly in the middle, hike it back, then swing it up to your chin level using your hips. Catch it bottom up by gripping the handle violently and tensing your abs. Drop the kettlebell back between your legs. Make sure to relax your arm. Several low rep sets totaling about 10 reps is all you need. This exercise does not tolerate fatigue. Eventually you may add bottom-up presses, front squats, and, if you are a stud like Max Shank, Senior RKC, even pistols to your arsenal. In addition to training kime and Yang breathing, bottom-up kettlebell drills forge a vise-like grip and unbendable wrists. Gray Cook also does some reflexive stabilization magic with them. For example, he improved the pullups of his wife Danielle Cook, RKCII who had problems firing one side of her abdominal wall, from 4 to 10 in one training session!

Bottom-up kettlebell clean.

Bottom-up cleans makes them a Yang exercise. The bottom-up kettlebell carry by Prof. McGill is pure Yin. He developed this drill after studying strongmen performing farmer’s carries. The scientist realized how important were the quadratus lumborum, deep small muscles running up and down on both sides of the spine, to health and performance. The QL tilts the pelvis sideways and it essential not only to strongman but to the contact sport athletes. “Consider the footballer who plants the foot on a quick cut. A strong and stiff core assists the hip power to be transmitted up the body linkage with no energy losses resulting in a faster cut.” For a fighter whose pelvis has to do all sorts of things during kicks the benefits are apparent. McGill prefers the bottom-up carry to the farmer’s and racked versions because the BU enforces core stiffness—you will not be able to grip the bell without bracing. The professor promises that the drill will improve your “athleticism”.

One of McGill’s revolutionary midsection exercises for fighters combines Yin and Yang breathing: the latter is periodically overlaid on the former. Start spinning a ball on the end of a rope over your head. (Fill your wife’s purse with something if you must, but don’t use a kettlebell). The professor instructs: “As the ball passes 12 o’clock the athlete pulse-stiffens the body. Then switching to other times such as 3 o’clock trains neurological dexterity. The emphasis is on rapid contraction and relaxation.”

McGill’s “Slamball helicopter”.

Courtesy Prof. Stuart McGill’s Spine Biomechanics Lab at the University of Waterloo, Canada

The above exercise is supposed to be done fast; sit-ups are not! Fast sit-ups not only ruin backs; they even have been known to injure the spinal cord and cause strokes! Don’t go there.

Enter the Kettlebell! www.dragondoor.com/b33

One more suggestion for practicing both types of martial breathing while getting a whole lot of other benefits: Hardstyle kettlebell practice. Take our most fundamental routine: the Program Minimum from Enter the Kettlebell! It consists of only two exercises: the get-up and the swing. Doing the former for several minutes non-stop (switch hands after each rep though), especially with a heavy kettlebell is an excellent practice of Yin breathing. The other drill, the swing, is a Yang breathing practice, each rep performed with kime.

Among the many benefits of such training is a very special type of endurance. Recent research65 has revealed a lot about the Hardstyle kettlebell “What the Hell Effect” when it concerns “conditioning.” The author reviewed the existing research on respiratory muscles’ fatigue and did his own. He found out that when these muscles get tired, they have a secondary unexpected and unpleasant effect on your ability to keep going. Metabolites in the diaphragm & Co. flick a switch in your nervous system that activates the fight-or-flight response and constricts blood vessels throughout the body. Therefore, “Respiratory muscle fatigue reduces limb blood flow, accelerates limb fatigue and increases limb effort perception.” The good news is, according to the scientist, conditioning your breathing will increase your performance in many endurance activities.

“Swings rock. Heavy swings rock more.”

It is hard to disagree with David “the Iron Tamer” Whitley, Master RKC. According to Alison McConnell, the British scientist who authored the above “Respiratory Muscle Training as an Ergogenic Aid” study, conditioning your breathing muscles will increase your performance in many endurance activities without an increase in the VO2max and/or the lactate threshold. This might at least in part explain the WTHE of simple heavy kettlebell swing routines not optimized to raise these two parameters on endurance in contact sports.

Photo courtesy David Whitley.

Max Shank, Senior RKC, a fighter and all-around stud, makes heavy swings the foundation of his conditioning. His standard workout is 5min of one-arm swings with the Beast, hitting 10 reps every time the clock beeps 30sec. This works out to about 100 swings total, 20 reps per minute and approximately 1:1 work to rest ratio. “If you throw in some finisher like this once or twice a week, you will be amazed at how everything you do starts to feel lighter and easier,” promises Max.

“Swings are where it’s at,” writes Michael Castrogiovanni, RKC Team Leader, who has been with us almost since the very beginning of our RKC program and who is responsible for introducing the Russian kettlebell to NSCA. “They always have been and always will be! It is the foundation of kettlebell movements and anyone who invests significant amounts of time in themselves with the swing will reap great benefits and not only unlocks the secrets of their hips but the kettlebell as well. I agree with Max completely, it is what I have been saying for years and in fact it is how I prefer to train with kettlebells.

For one year I did nothing but swings, every which way, even though I had learned to clean and snatch, instinctively I knew the value in this foundational movement. After several months of swings I decided to return to wrestling, it had been a while due to injury (not from kettlebells) and I wanted to test the functionality and carryover of my newly forged strength. The two most important gains I noticed that translated from my training to the mat were: I was able to defend takedowns against guys who used to take me down at will, because I had more power and endurance in my sprawl. I also had longer lasting power endurance for takedowns late in the match when historically I would be too gassed to even attempt a takedown. I remember thinking how easy it was to maintain wrist control and how strange it was that my hands, wrists and forearms did not get sore despite my long break from wrestling.”

Castro offers a few simple and powerful kettlebell swing routines.

The 10x10

Do 10 sets of 10 reps with a bell with as little rest as possible. If it is too easy, try another set; still too, easy add weight; still too easy add a bell. Try this protocol for 10 weeks. Stick with the same weight for 10 weeks and see what happens. 3 times a week

The 10x10 pyramid

Same as before, except increase your weight each set to five. Descend in weight for the last five.

The 10x10+10x10 diamond

Same as the pyramid but now go through the increase and decrease one more time to complete the Diamond.

Make sure you are outside and you have a place to throw the bell. After your 100th rep throw the bell as far as you can. This promotes that explosive endurance for the late in the game take down, when you don’t think you’ve got anything left in the tank. Try it, practice it, you will be amazed!

“I have done almost every swing/snatch combo workout imaginable,” states San Jose University head strength coach Chris Holder, RKC Team Leader, “and I always end up back to heavy swings...”

“Coach, I just don’t get tired!” This is music to Chris’ ears.

VO2max is not the only determinant of endurance.66 For example, in the earlier mentioned studies of bicyclists and distance runners improving their endurance with heavy strength training, no change in maximal oxygen uptake was observed either. A serious athlete from a contact sport should address all aspects of his conditioning with appropriate methods: VO2max, lactate threshold, respiratory muscles’ strength and endurance, absolute strength.

5. Provide reflexive rotary stability.

Item #5 on our list, rotary stability, refers to reflexive coordination of multi-plane movements engaging both the upper and the lower body. As Gray says, “You can’t Hardstyle rotary stability”. You may be strong as a bear in the full contact twist, yet if your core does not properly function reflexively, you will not be able to coordinate techniques like the Thai roundhouse kick well. Although rotary stability is developed by the kettlebell get-up, it may not be enough. Testing and correcting rotary stability is outside the scope of this book, refer to a CK-FMS instructor, www.dragondoor.com/instructors/ckfms_instructors/.

For obvious reasons grapplers need to be strong in the curled up in a ball position. A simple way to develop such strength while improving your pulling strength and making your elbows healthier is to take a page from the book of Steve Baccari, RKC and do chin-ups finished by curling up in a ball and holding this position.

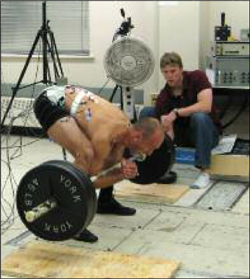

Wrestlers need be able to lift their opponents from very uncomfortable positions. The Zercher deadlift (see the photo) is a dangerous yet effective exercise. Alexander Karelin has done 440x10! Although the upper back will unavoidably flex, do your best to keep your lower back flat and “hinge” through your hips.

Courtesy Prof. Stuart McGill’s Spine Biomechanics Lab at the University of Waterloo, Canada

If all of the above seems overwhelming and complicated, just follow the Enter the Kettlebell! Program Minimum with a heavy kettlebell, eventually 32-48kg. Yes, it is that simple.