Turning grapes into wine is a most amazing, magical procedure. How winemaking actually came about is not known. Perhaps it started with prehistoric people, who gathered wild grapes in order to use their sweet juice as a thirst-quencher. Having left some in a vessel of sorts, they discovered it had evolved into a different drink, one that made them happy and elated. The grape juice had fermented and turned into wine. Maybe this started the ball rolling and launched mankind’s fascination with turning the simple fruit into this wonderful nectar.

As time passed, winemaking became more and more complex and sophisticated. Innovative technology helped overcome basic obstacles in the process, allowing the grapes’ individual characters to come through. Now the winemaker was free to create, mold, and sculpt these liquid delights into personal expressions of art. Although computers are a large part of modern winemaking today, it is still the winemaker’s input and direction that determines what goes into the bottle. This is the part of wine where the makers have the most say.

Aside from the details, the general process of winemaking is relatively simple. When the grapes arrive at the winery, they are initially separated from the stuff that is not needed via a crusher/destemmer machine. This unit lightly crushes the fruit and eliminates the stems and pips (seeds). Then the remaining mash is pressed to produce juice. The juice is then fermented in some format, cleaned up, aged for some time (possibly in wood), and bottled.

WINE PRODUCTION

Wine Making Process

Three main categories of wine result. Still wine, including reds, whites, and rosés, is the most common. Reds utilize the skins for colour and tannin. Most whites do not utilize the skins, so there is no colour to be had. Even white-skinned grapes possess tannins, bitter oils, and phenols which could affect the finished wine, making it bitter. Rosé uses the skins, but carefully.

Sparkling wines are those into which bubbles have been introduced through some process.

Finally, fortified wines are made by adding pure grape spirits or brandy to wines during some point of their production.

The art of winemaking is a process of creation, not unlike raising children, then sending them off. It’s not uncommon to hear winemakers refer to their wines as their children. Think about it. They give them life, mold, direct, and shape them. Finally they send them out into the world or down someone’s hatch, as it were (that last part of the process is not like raising children).

Although the winemaking process is generally quite simple, the knowledge required to make wine successfully is very complex. The winemaker needs to have more than a basic understanding of biology and chemistry. Since much equipment is utilized in its creation, technological expertise is also required. And since wine is something that is appreciated orally, he or she should possess a reasonably decent palate, as well. After all, what good is producing a biologically and chemically sound wine using modern equipment if it tastes like shoe polish? Take the amateur or home winemaker. Like the “bathtub gin” produced during Prohibition, without scientific knowledge about blending et al., the amateur’s end product can often be unsophisticated and harsh. Bathtub gin, in some cases, actually caused blindness.

THE GRAPE

I’m having an argument with a friend. He says the skin of the grape is the most important part of winemaking. I say it’s the pulp. Who’s right?

Diagnosis: Since there aren’t too many red grapes in which the pulp is red, the skins must be included in the making of red wine to give colour. If we examine what is required for wine from the grape we can easily resolve this disagreement. The grape contains pectins, fruit acids, sugar, and water. Yeast feeds on the sugars in the grapes, producing carbon dioxide and alcohol. Fruit acids within help balance out the sweetness of wine in the flavour. Pectins, or the jelly-like interior of grapes, act as the vehicle to carry both of the aforementioned sugar and fruit acids.

In essence you are both correct. Without the pulp there would really be no wine. If it were not available, we would need a knife and fork instead of a glass to enjoy it. Certainly the pips or seeds and the stems can be removed, as they contain bitter oils and phenols that would make wine taste weird. Without skins, however, very few wines would be red in colour.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

When professional tasters describe wine, they talk about all kinds of fruits, vegetables, flowers, and so forth that they smell and taste. Are these things actually used in the winemaking?

Diagnosis: If I had a dime for every time this question comes up I’d be a rich “wineknow.” Many things in everyday life are used to describe the smell and taste of wine. Every possible food, flower, spice, and chemical seems to come into play at some point.

These descriptors simply help communicate the language of wine (I heard it through the grapevine). The only product used in making grape wine are grapes. All the other descriptors are a product of its production. Wine is one of the few products on earth that contains so many smells and flavours.

Is there anywhere in the world where grapes are still crushed by foot?

Diagnosis: Check out Dr. WineKnow’s house on Saturday night, and experience his own version of “bathtub claret.” Or you could look back to the Greek and Roman times, when it was the only way to lure the juice from the grape. Since the advent of modern technology, grapes around the world are crushed mechanically in most commercial winemaking. It’s certainly much faster, especially with the volume some producers are processing.

Stomping the grapes by foot is still popular among some home winemakers in certain parts of the world. To see it used commercially, however, you’ll probably have to look to Portugal and the production of port. It would seem that many producers are going back to this traditional method of crushing grapes, because they claim it yields better-quality wines. Here grapes are placed in shallow stone tanks called “lagares” and trodden by barefoot men and women for up to six hours. The slow crushing of the grapes extracts maximum colour without breaking pips and stalks, thus reducing tannins and acids. Would you believe the natural warmth from human legs slowly raises the temperature of the must (fermenting juice) enough, allowing the yeast to go to work on the sugars? From personal experience, I can tell you it is very hard, foot-staining work (as a side note, it took two weeks for the dye to wear off my legs and feet).

GRAPE FLASH

Did you know that all parts of the wine grape are utilized for something? Obviously, the most important parts are used for the wine. However, the pips (seeds), stalks, and skins of white grapes are sometimes watered down, refermented, and distilled into a brandy of sorts (marc in France, grappa in Italy). If this is not done, the residue is reintroduced to the vineyard as compost. Nothing goes to waste.

Why are some red wines soft and round, while others are hard and aggressive?

Diagnosis: There could be many reasons for this, including the grape(s) used, oak contact, and fermentation temperatures. The most common reason, however, is the type of press used to extract the juice. Grapes that are hard-pressed are usually crushed in a press where metal works against metal, literally squeezing the life out of the grapes. When this happens, many bitter, harder components from the skins remain in the juice – and ultimately in the finished wine. Wines that are soft-pressed utilize a press where an inflatable rubber bag fills with air and delicately seduces the juice out of the grape without many of the harder components from the skins.

Prescription: Read the back label of your wine carefully. Occasionally, it will mention how the wine was made. Otherwise, pick better-quality wines. These will often be more expensive, but most of the better wines are made through a soft press.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

When touring wineries I’ve noticed that most use stainless-steel equipment. What’s the benefit of this?

Diagnosis: Stainless steel provides the most neutral of environments to ferment wine. There’s absolutely no personality about it; no extraneous aromatics or flavours will be imparted to any wine produced in it. The containers also come in jacketed formats that make it easy to run hot or cold water over them, thus controlling fermentation.

Prescription: Have you got a lot of money? If so, buy stainless steel. Winemaking equipment is very expensive. Unless you are an extremely serious amateur winemaker or are planning to go professional, it’s probably best to make do otherwise.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

Is there a difference in how “Old World” and “New World” wines are made?

Diagnosis: More than a geographical description of where the grapes are grown, these terms refer to a philosophy about winemaking. “Old World” winemaking seems to highlight “terroir” (the soil and climate that the grapes are grown in) in their wine, with the fruit (sweetness) in the background. The use of oak is also much subtler. “New World” winemaking tends to produce wines that are fruit-driven, with more aggressive use of oak. Terroir is understated.

It’s a toss-up really. It is extremely interesting to taste wine with people who grew up with both influences. The difference in likes and dislikes as far as their palates go is fascinating. It’s really a matter of what you are used to.

Fermentation is the process by which grape juice becomes wine. It’s a rather simple equation. The sugar in grape juice is converted into alcohol and carbon dioxide via the action of yeast. The wine-maker has at his or her disposal several techniques by which to do this: natural fermentation, malolactic fermentation, barrel fermentation, and carbonic maceration. The resulting wine’s character can be somewhat altered, providing varying characteristics in the finished wine.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

I’ve tried making wine at home but find it very hard to control fermentation. Sometimes it just stops. What am I doing wrong?

Diagnosis: Fret not, my friend, your problem is simply explained. It’s not so much what you are doing but what you are not. Fermentation generates heat. If the temperature cannot be controlled, decent wine, if any, cannot be made. This was the problem with many a winemaker years ago. The yeasts that are used to ferment wine are very sensitive to heat and cold. They operate best between 5°C (40°F) and 30°C (90°F). If the temperature goes outside this range, then fermentation will stop, as you’ve experienced. This is known as “sticking,” and sometimes it can’t get unstuck to start again. Even if it restarts, changes may have taken place in the sugars to spoil the wine. In one case in point, my father-in-law decided to make his own wine, using the crab apples in his backyard. Since he had no previous experience and had never read anything about winemaking, his end product was high in alcohol and the fermentation process resulted in undue pressure in the bottles. In the middle of the night, you could hear the sound of corks exploding off the tops of the bottles. Interesting wine, though! Put hair on your chest.

Prescription: You “must” follow this advice. To avoid this danger, the must (fermenting juice) may have to be cooled in warm weather and heated in cool weather. If you are using tanks, this can be achieved by pumping cold or hot water over them. Unless you are relatively serious about home winemaking, you may want to rely on one of those “ferment-your-own.” wine facilities that are springing up all over the place. They have temperature control.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

I often buy grapes to make my own wine. What’s that grey, waxy stuff on the skins of all grapes that doesn’t wash off?

Diagnosis: This fascinating haze or bloom on each grape is a blend of wild yeasts, wine yeasts, and bacteria by the millions. They are carried on the wind and by insects. The wine yeasts, in particular, were important to early winemakers, since they were necessary for “natural fermentation.” Once the skin of the grape is broken, these wine yeasts feed on the sugars within, producing alcohol and carbon dioxide and making wine.

Wines today can still be produced through “natural fermentation,” but much attention should be paid to the following: fermentation must take place in an airtight container to ensure killing the wild yeasts and bacteria present on the grape skins. Furthermore, be prepared for a long wait, as this process is very slow. That’s why most winemakers today don’t rely on it. (If wine is inoculated with artificial yeast, such as most winemakers use, it overrides any natural grape yeast that exists.)

GRAPE FLASH

Did you know that winemakers of today inoculate the must (grape juice) to initiate fermentation? They actually throw some specially designed, fast-acting yeast into the fermentation vessel to start things going. Occasionally they will add some already-fermenting wine to get the ball rolling. Exactly what yeast is used by each winemaker seems to be a big secret. They don’t often like to divulge the specific strain they use for particular wines.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

How do they get that buttery character in wines like Chardonnay? I really love that creamy complexity.

Diagnosis: Actually, that buttery character is the result of “malolactic fermentation.” This secondary fermentation, stimulated by a bacteria (leuconostic oenos), takes place naturally, reducing harsher malic acid (the kind found in green apples) into softer lactic acid (the kind present in milk). Overall, it tends to make the wine more stable. It can be controlled by winemakers (they can inhibit it if desired).

Prescription: It’s better with butter! Malolactic is more beneficial to some grape varieties than to others. As a general rule, wines produced in cool climates possess higher acid levels and benefit from “malolactic fermentation.” Warm-climate wines are often lower in acidity and may need to be prevented from going through MF so as to retain whatever is available. That is done by keeping wine at cool temperatures or not inoculating with lactic bacteria. (Sometimes the addition of sulphur dioxide also prevents MF.)

On the back label of some wine bottles, the term “barrel-fermented” is used with reference to the wine. Could you explain this method?

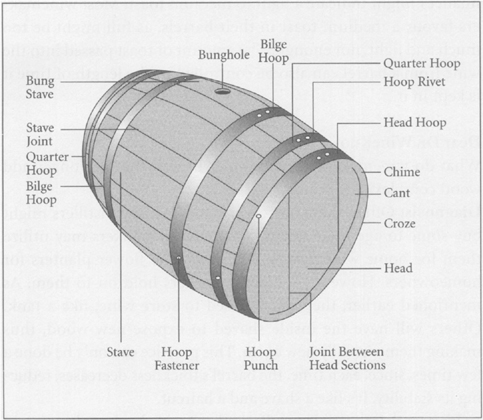

Diagnosis: Some winemakers choose to ferment certain wines “in barrel.” This technique is used principally for white wines, as it is too hard to remove the skins in red wine through the small bung hole of a barrel. Chardonnay and some fine sweet wines are made this way, and there are certain benefits to the method. The barrel protects the wine from oxygen during fermentation. It allows for the controlled extraction of wood flavours into the wine. Because barrels have a large surface-to-volume ratio, artificial temperature control is seldom needed. It also makes it a lot easier for barrel ageing and lees (dead yeast) contact, as the wine is already in the same container.

Although “barrel fermentation” does a great job of adding richness and length on the palate, it does have a few disadvantages. Barrels are much more labour intensive to clean, fill, and empty than are tanks. Overall, producing wine in barrel is more costly. This is why this method is usually reserved for higher-priced wines. The extra degree of complexity gained often outweighs the extra costs.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

Beaujolais is my favourite red wine. It’s always so deeply coloured yet soft and round without any of the hard tannins of other red wines. How so?

Diagnosis: Carbonic maceration. Sounds yummy, doesn’t it, kind of like chewing bubbles. Beaujolais utilizes this technique for making wines soft and consumable earlier – which has been around for ages. With carbonic maceration, the grapes are generally not crushed but thrown into an airtight fermentation vessel, whole or in bunches. A blanket of carbon dioxide covers the intact berries and actually suffocates them. Fermentation takes place within the cell walls of each grape, causing colour to leach out of the skins into the pulp and juice. Because the skins are not crushed, very little tannin and, ultimately, bitterness is extracted from them.

Caution should be taken with this technique. The concept of 100 per cent carbonically macerated wines is really elusive. The mere pressure of some grapes on top of others breaks skins, allowing natural fermentation to take place as well. Thus the term “carbonic maceration” is applied to any situation where there is a proportion of wine being fermented this way. Winemakers will often carbonically macerate some grapes and back-blend them in to his/her satisfaction.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

What do we get by blending red and white grapes together?

Diagnosis: Why, rosy cheeks, of course. You might think this is how rosé is created, but it isn’t as a rule. Almost everywhere in the world rosé wine is made by leaving red grape skins in contact with the fermenting juice just long enough to obtain the desired colour, then removing them. Blending red and white wines together is usually frowned upon, except in Champagne, where they actually blend some still, red wine into the mix before the second fermentation to make the wine rosy.

Prescription: Rosés come in different formats, too. Sometimes they are called “white Zinfandel” (made from Zinfandel grapes), “blush,“ or “Blanc de Noirs.” All of these will ensure a pretty-coloured wine, meant to be consumed young – for the most part -probably within the first three years of the vintage on the bottle.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

What happens if a wine doesn’t produce enough alcohol? Do they just pitch it?

Diagnosis: If you are looking for the “best buzz for your buck,” alcohol is one of the key ingredients in wine. For most consumers, though, it also provides structure and longevity to a wine. Alcohol is a direct result of the amount of sugar in the grapes at the time of harvest. During fermentation, the yeast feeds on the available sugar, producing alcohol and carbon dioxide. The more sugar available, the more alcohol can be produced. Occasionally, sugar levels in grapes are low in cool viticultural areas, especially in poor growing seasons. Thus, fermentation maybe fighting to produce reasonable alcohol in a wine.

Prescription: When this happens “chaptalization” may be used. This is the addition of sugar to the fermenting must to increase the alcohol (not the sweetness). This procedure is not allowed in certain wine regions around the world, such as Italy and other warm viticultural areas.

GRAPE FLASH

Did you know that sometimes certain finished wines do not contain enough acid (the sour component) to balance them? Acid levels in wine are extremely important to their structure. Without enough, the wine comes across as “flabby” or “cloying“ in the mouth. The process of adding more acid to a wine is known as “acidification.” It is not allowed by the regulatory bodies in some wine regions. This lack of acidity can be a major problem in warm viticultural areas, so in this case some acid adjustment is allowed.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

What do winemakers do with wine produced in a poorer year, especially if it is an expensive one?

Diagnosis: I dunno, throw it out? Hey, not every year is great for growing grapes. There are a number things a grower can do in the vineyard to reduce the yield and concentrate the fruit in a poorer year. Even the winemaker can do just so many things in the winery to increase the quality of poorer fruit. But often, even after utilizing all vineyard and winemaking techniques, the finished wine for an upscale product is still mediocre.

Prescription: The producer would either use it in a blend, download it to a more commercial wine, or create a rosé – if it’s red. If it is really inadequate, they may just use it for brandy production. Occasionally, they will create the original wine, but charge less for it. Truthfully, it’s not to the producer’s advantage to market an upscale wine that is simply not up to snuff. There is a reputation involved here.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

How do I know if a winemaker is good at what he or she does in a great vintage? Everybody out there is making decent wine.

Diagnosis: The bottom line is one can only make as good a wine as the raw material that is started with. You’re right that, in great years, everybody should be making great wines.

Prescription: Pay attention during poor vintage years and take the time to judge a winemaker’s ability. Someone who can take less than adequate or mediocre fruit and create a decent wine has what it takes. Take not this time to “whine” over wine, but to build up knowledge about makers for the future.

Nothing quite tickles the nose and excites the palate like a glass of bubbly. No other wine in history has become as synonymous with celebration. This launcher of ships, symbol of the high life, and official wine of the “occasion” has earned its world-famous reputation mainly because of the “fizz.” The fizz, of course is what sparkle is all about. Getting it into the wine is the art.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

Why is Champagne so expensive? Is it just because it comes from France?

Diagnosis: Mais non, mon ami! The reality is that the method of production and quality of the wine produced drives up the cost. The “champagne method” produces the best bubbly with the smallest bubbles that last the longest in the glass. But it is also extremely labour-intensive, involving two fermentations: the first to make the wine and the second to create the bubbles. Furthermore, it blends many wines together to come up with a specific taste. Most importantly, the second fermentation takes place in the same bottle. The whole process is very specifically spelled out in Champagne, France.

Prescription: If bubbles tickle your fancy, but you don’t want to pay the Champagne price tag, there are alternatives. Look for wines from other countries that are made this way. Somewhere on the bottle they will say “champagne method.” “traditional method,” “second fermentation in the bottle,“ or, in Spain, “cava.” These might cost a bit more than other bubblies that are made differently, but the cost is nowhere near that of Champagne.

GRAPE FLASH

Did you know that “riddling” was not the sole domain of Batman’s arch-enemy, the Riddler, but a major part of the champagne method, as well? After the second fermentation, the dead yeast must be removed from the wine. Traditionally, the bottles were gradually tilted from a horizontal to a vertical position and shaken, all by hand, to get this deposit to settle at the neck, so it could easily be removed. This slow process, taking six or more weeks, was done in a “riddling rack” or pupitre, a sandwich-board type of wooden unit with holes. However, this tedious manual method takes a long time. It was the Spanish back in the 1970s who came up with an automated version to speed up the process. Enter the gyropalette, or “pupimatic,” as I like to call it. This computerized machine, capable of holding hundreds of bottles, mechanically tilts and shakes the entire mass at specified, programmed times, reducing “riddling” to three or four days. However, some producers still prefer to hand-riddle their bubbly today.

I like bubbly but I can’t afford even “champagne-method” wines. As a student, I have a Mercedes taste on a Volkswagen budget. Is there anything out there for me?

Diagnosis: There sure is. Bubbles can be put into a wine three other ways. Mind you, the quality overall may not be as good. The next best method, after the “champagne method,“ is the “tank method” – often called “Charmât,” after the chap who invented it, or “cuvée close.” There are two fermentations here, but the second takes place in a large tank. The wine is then bottled under pressure to preserve the fizz. Then there is the “transfer method,” which is rather interesting. The wine in this case is second fermented in the bottle, but then dumped into a large tank to clean it up and rebottled under pressure. Finally, the method of least quality is “carbonation,” or “injection.” A single fermented wine simply has carbon dioxide pumped into it. The resulting wine possesses large bubbles that disappear very quickly.

Prescription: You don’t have to sacrifice good taste. Some bubblies will mention the method of production on the bottle. California, by law, is obliged to put it on wine labels. If the bottle says nothing about the method of production, it is probably safe to assume, in most cases, that it utilizes something other than the “champagne method.” German sparkling wine generally uses the “tank method.” If in doubt, ask your retailer. Price is also generally a good indication of method of production. “Champagne-method” wines are the most expensive and “carbonation/injection” wines, the least.

Fortified wines are the big guns of the still wine set. These powerful numbers are not for the weak of heart. They contain anywhere from 15 to 24 per cent alcohol by volume. They can pack quite a punch, so they should be consumed moderately. When fortified wine happens to be sweet as well, its stability and staying power are incredible, more so than any other wine.

What exactly does fortification do for a wine?

Diagnosis: Fortification is the process of adding brandy or pure grape spirits to a wine. It originated many years ago, when the addition of brandy helped preserve a wine on long ocean voyages. World-famous port and sherry are made this way. However, the point at which the brandy is added differs with both wines. Port has the brandy added during fermentation. When 40 per cent alcohol is added to a fermenting wine, the yeast is killed on contact. Since the yeast has not yet consumed all the sugar, much of it remains in the wine. That’s why most port is sweet. Sherry, on the other hand, has the brandy added after fermentation. All sherry is fermented to a bone-dry state, then fortified. Sweet sherry is produced by adding back some sweet wine.

Fortification helps wines live long, since alcohol is a great preservative. Most ports and sherries will live comfortably for decades.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

I’m into aroma therapy, but what on earth is “aromatized wine”?

Diagnosis: An aromatized wine is a fortified wine (grape brandy added) that has had other flavouring agents macerated into it. Herbs, roots, flowers, plants, seeds, barks, peels, and nuts give this fortified wine unusual aromatics and flavours. One of the classic examples is vermouth that is flavoured with such things as nutmeg, coriander seeds, cloves, cinnamon, rose leaves, quinine bark, hyssop, angelica root, wormwood, chamomile, orange peel, and elder flower, to name a few. It’s a regular smorgasbord of earthly delights.

You may not want to dab a little behind your ears, but if your taste leans to the exotic, perhaps this type of wine is for you. Just keep in mind that, being fortified, they contain more alcohol and can do a number on you. Drink sparingly, or you may find yourself doing a horizontal tasting.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

I was in a French restaurant the other day and noticed the term “vin doux naturel” (naturally sweet wine) on their wine list. Is this like late-harvest wine?

Diagnosis: Contrary to the English translation, these wines could actually be considered “unnaturally sweet.” Normally, sweet wines contain so much natural sugar that yeasts cannot convert it all to alcohol and die off leaving much behind, VDN, as it is called for short, has pure grape spirits or brandy added to it halfway through to stop fermentation (fortification). This kills the yeast on contact, preventing it from converting the rest of the sugar. The resulting wine is sweet, with dominant grape flavours, and strong, with more than 14 per cent alcohol.

If you have a hankering for this type of wine, some delicious offerings are available from the south of France and usually represent great value. You had better like the muscat or grenache grape, though, as most are normally made from these.

Over the years, certain general expressions and terms describing wines have evolved. They have almost taken on stylistic cult status. Some of them are not even formally acknowledged but are used more colloquially. It’s amazing just how powerful many of these are in conjuring up and denoting a particular image of a wine.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

I’m hot on the trail of “table wine.” I’m discovering that it seems to mean different things to different people.

Diagnosis: Elementary, my dear Watson. There is an interesting dual meaning to this term. For most wine lovers, the generic term “table wine” refers to everyday wines that we drink with meals or on their own. These can be red, white, rosé, sparkling, or fortified. In wine areas, it’s a different story. The term here usually means simple wines with the lowest-quality production standards. In fact, in many countries, table wines actually contain wine from other countries. As long as the minimal required percentage comes from the country stated on the label, the rest can come from anywhere. The grapes from the stated country also usually come from all over the country, not from any specific region. Although cheap and cheerful, these wines don’t usually provide great gastronomic pleasure.

If you want reasonable quality, stick to wines that come, at least, from a particular region. Better still are those from individual villages. The best come from single vineyards and are labelled Château or Domain something or other. (Outside France, they’re Estate or Vineyard.) If you must consume table wine, try to choose those that have a grape variety on the label.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

On a vacation in California, I noticed a fair amount of “jug wine” being sold. Is this a particular style of wine?

Diagnosis: “Jug wine” is the American equivalent of “vin ordinaire“ or “plonk.” usually sold in larger sizes. After Prohibition ended in 1933, most inexpensive California table wine was bottled in half-gallon and gallon jugs or flagons to cater to thirsty immigrant labourers from the Mediterranean and eastern Europe. Gallo was one of the pioneers of this practice. However, as this generation aged or passed on, newer generations with more sophisticated palates turned to such things as “fighting varietals.”

After all, how serious can a wine be that conjures up images of a “jug band”? There are still a number of jug wines available today. Their modest price and large size make them ideal for parties or large gatherings where the key is quantity rather than quality.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

What on earth is “plonk”?

Diagnosis: This rather vague term does not refer to a style of wine. It’s an English expression used commonly to describe a wine of undistinguished quality. Word has it that it originated in Australia as an Anglicized form of the word “blanc,” French for white wine.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

Are “blush” wines and “white Zinfandel” the same thing?

Diagnosis: Most are sweetish, lightly fragrant, and faintly spritzy. Would you believe these lightly coloured wines made from dark-skinned grapes, emanating from California in the late 1980s, were a marketing triumph? Surplus Zinfandel grapes, turned into rosé and called “blush” or “white Zinfandel” were and remain the dominant type, and are still very popular today. In fact, they spawned many other pink wines, such as white Grenache, Cabernet Blanc, Merlot Blanc, and Blanc de Pinot Noir.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

I’m into Italian wines and those from Tuscany are my favourite. I see some wine shops advertising that they sell “Super-Tuscan” wines. Are these made a special way or something?

Diagnosis: Yes, it’s Super-Tuscan – a mild-mannered wine by day, a veritable gem by night. These wines acquired their names as products that were produced outside of DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata) and DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita) laws. In other words, the producers didn’t follow the production standards of a specific appellation in Tuscany, and so could not put that indication on their label. They may have been created from lower yields, contain grape varieties or percentages that were not allowed, and so on. Because of this, they can only be labelled as “vino da tavola” (table wine).

Many of these wonderfully-made, age-worthy numbers are on every collector’s list and have garnered worldwide acclaim. However, they’re “super” not only in quality but also in price. Most are expensive, in limited supply, and usually sell out very quickly after release. Incidentally, this concept has spread to other Italian wine regions, and “Super-Italia.” wines are popping up all over the country.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

What’s all the hype about “nouveau” wines? It seems most countries are now producing them.

Diagnosis: As you probably know, the word “nouveau” is French for new, and that’s exactly what it’s all about. Although it was the French that started it, this phenomenon has now spread to other wine-producing countries, and most make this style of wine. The concept is to create a red wine from the new harvest, as quickly as possible, to help celebrate it. In doing so the wine is usually carbonically macerated like Beaujolais, fermented for only about four days, and aggressively stabilized. As a result, a fruity, soft, aromatic, easy-drinking, youthful red is produced. Beyond what the wine stands for is the incredible marketing savvy involved. Marketing 101 teachers around the globe would be delighted. Through the hype created before its release (the third Thursday in November annually for the French, though dates vary for others), enticing people to be the first to taste the new wine of the vintage, it creates a buying frenzy that is astonishing. In fact, in this period most producers cover the cost for the production of their entire vintage, making any other revenue from their remaining wines total profit.

Prescription: Do use this refreshing, uncomplicated little number as a great excuse to get down and par-tay! Don’t buy this style of wine expecting great complexity and ageing ability. It’s just not that kind of creation. Served cool, “nouveau” wines are best consumed within weeks rather than months or years after the harvest. Although it’s not unheard of for a well-made nouveau from a good vintage to be fine even after two to three years, drink it young.

GRAPE FLASH

Did you know that the excitement and sales of “nouveau” wines are on the decline? With most countries around the world producing “nouveau” of sorts, it’s not surprising to see sales fall somewhat. Overall, there’s simply more of it out there. I’m sure some of the pricing has not helped either. Since it’s usually bottled with artistic, avant-garde labels, and depends on expensive marketing, it’s hard to keep the cost down.

However, I believe there is a way to breathe new life into the “nouveau phenomenon. Sell it in bulk. Set up large tanks in malls, shopping centres, and wine shops and have people bring empty containers or bottles that can be filled for so much a litre. Do away with the packaging altogether. Although the presentation may suffer, think of all the savings on bottling and labelling on the producers side. The great bottom line is the cost to the consumer, at a fraction of the price of the bottled version. This tactic, I believe, would ignite interest and sales again. If “nouveau” really is a celebratory wine that should flow freely, this is probably an ideal venue for it.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

What’s the story with “de-alcoholized” wine?

Diagnosis: It’s the never-ending story of truth, justice, and, recently, the Canadian way. These styles of wine are becoming more popular as consumers combat the problem of drinking and driving, as well as health issues. They also contain fewer calories, so folks on calorie-restricted diets can imbibe. Wine can be de-alcoholized in several ways: vacuum distillation; evaporation under vacuum and inert gas at low temperatures; reverse osmosis; and pervaporation. The resulting alcohol usually ranges from less than 1 per cent to around 2 per cent.

All processes of removing alcohol are expensive and the cost may be passed on to the consumer. Aww, no fun. Once the alcohol is removed, wine loses its stability, so it is even more important to practise sterile, hygienic bottling to avoid bacterial infection. These wines don’t have great staying power either, so immediate consumption after purchase is best.

The use of oak treatment in wines is an interesting topic. Much of the expense of making wine comes from the use of oak barrels, and their expense is inevitably passed on to the consumer. However, for many wines on the market today, oak is an integral part of their production and flavour profile.

Why is oak the wood of choice for treating wine?

Diagnosis: Believe me, producers over the years have experimented with many different kinds of wood. In California they even played around with redwood, but it didn’t work. Some places in Europe still use chestnut and cherry wood, but these don’t really add anything to the wine. Some wood is too soft and transfers odd flavours to wine. Others are too porous. Oak was finally decided on for some very good reasons. It is hard, supple, and watertight. It displays a natural affinity to wine, imparts qualities and flavours that are complementary and enhancing, and is relatively easy to work with.

The grain in oak is very important to wine. Wide-grained oak tends to be more tannic than tight-grained. From wide-grained oak, more wood character comes through into the wine. Tight-grained oak supplies subtler influences. Not just any species of oak will do, either. There are two main categories, red and white. Red is porous and not reliably watertight, so white is most commonly used. All oak is either air- or kiln-dried. The air-dried process is slower, and usually provides better oak for barrels.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

Why are wines oak-treated?

Diagnosis: Wine is wood-treated by a winemaker for several reasons: to harmonize and marry flavours, soften and round out the palate, add wood complexity, and reduce tannins in red wine.

Ultimately, it’s the winemaker’s decision to oak-treat a wine or not, depending on the style he or she desires.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

Not all grape varieties seem to come in contact with oak. Why do some get it and others don’t?

Diagnosis: Certain styles and grape varieties don’t have a natural affinity to the character that oak adds. In these cases it just doesn’t mesh and harmonize, or totally overpowers the wine. If the wine is delicate, light, or fruit-driven, oak is generally not used, and the wine does better without it. Wines that are meant to be consumed over the short haul, say within a few years of the vintage, don’t usually see it either.

Some wines that would fall into this category are Beaujolais and its nouveau versions, Grignolino, Dolcetto, Frascati, Pinot Bianco, and Soave. Some grape varieties that don’t usually utilize oak are Riesling, Gewürztraminer, Muscat, Vidal, Pinot Grigio, and Gamay.

GRAPE FLASH

Did you know that there is such a thing as too much oak influence? This is a major ongoing concern among both wine-makers and consumers the world over. Oak usage should compliment and enhance a wine, not overwhelm and dominate it. There are many wines on the market today that are over-oaked. Sometimes certain wines are not structured for the amount of oak utilized. When there is too much oak in a wine, it’s hard to experience the fruit and other complexity. It may even be difficult to decipher the grape variety. It also makes it hard to drink and increasingly difficult to match to food. However, not all of this can be blamed on the wine-maker. The world’s love affair with massive oak in wines helps stoke the fire. The winemaker is only catering to consumer tastes. The next time you smell and taste a wine that offers up aggressive oak overtones, above all else, consider this: If the only thing I’m experiencing is wood, then maybe “Château 2 X 4” is not a great drinking experience. If a winemaker has to oak a wine to this point, one has to wonder if he or she is trying to cover something up – such as poor winemaking.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

I’ve noticed that wine that has been aged in oak longer displays more wood character than those aged for a shorter time. Is it as simple as prolonged exposure?

Diagnosis: Wood character is quite important in wine. It adds aromatics and mouth feel and softens and rounds out flavours. The simple answer to this question is, yes, it is a matter of prolonged exposure. The more time the wine spends in oak, the more influence the oak has on it.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

Does the age of oak make a difference?

Diagnosis: You bet your cask it does! The newer the oak, the more interplay between wine and wood, and, ultimately, the more oak complexity that transfers into the wine. In fact, after three or four years, an oak barrel imparts little wood flavours to a wine. It merely acts as a receptacle.

Chances are, when you smell and taste a wine that displays a lot of vanilla, new oak has been used. Older oak will give less vanilla notes and subtler characteristics to a wine. Given the price tag of new barrels, you now know why certain wines that are always aged in new oak are so expensive. Every year, the winemaker must invest in new barrels for that particular wine. Ladies, out of perfume? Dab a bit of this wine behind your ears; it will drive the men simply wild.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

In France, I tasted the same wine out of different-sized barrels. Boy, what a difference in aromatics and flavours!

Diagnosis: The size of a barrel makes a huge difference in imparted flavours. The smaller the barrel, the more interplay between wine and wood. Again, more oak complexity is transmitted. The larger the barrel, the less influence.

I hate to re-state the obvious, but size counts. If the wine exudes lots of vanilla notes, more than likely, it was aged in smaller, new oak barrels.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

Certain wines I taste seem to have a toasty character. Sometimes it’s stronger than in others. Why?

Diagnosis: You’ve heard the expression, warm as toast? Wine-makers can, and often do, order barrels charred or toasted on the inside to their specifications. Of course, they can purchase them straight up (untreated), if desired. Yes indeed, the barrels are actually turned upside down over an open flame and charred to the winemaker’s request, usually light, medium, or full toast. The wine that ages in these charred barrels takes on the flavour and degree of the toast.

If you taste a wine that delivers real smoky aromatics and flavour, a full toast was probably used in the preparation of the barrel the wine was aged in. More delicate toasty, biscuity, nuances might indicate a light to medium toast. Most winemakers favour a medium toast in their barrels, as full might be too much and light, not enough. The amount of toast passed into the wine from a barrel can also be controlled by the length of time it is kept in it.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

What do winemakers do with older barrels that no longer add wood complexity to wine?

Diagnosis: Often, these barrels are sold. Whisky distillers might buy some to age their spirits. Amateur winemakers may utilize them for home winemaking. Many become flower planters for homeowners. However, some winemakers hold on to them. As mentioned earlier, they can be used to store wine, like a tank. Others will have the inside shaved to expose new wood, thus making them virtually new again. This practice can only be done a few times, since, each time, the barrel’s thickness decreases, reducing its stability. It’s like a shave and a haircut.

It’s next to impossible to tell whether a wine has been kept in old barrels, because if they are used no apparent wood complexity exists. It’s also difficult to figure out whether a wine has been aged in a shaved barrel or not. One thing is certain. There is probably not a winemaker on the planet who will admit to ageing wine in shaved barrels.

Did you know that wine aged in barrel loses up to 10 per cent of its volume due to evaporation? Oak is an interesting material. Because of its grain, it tends to be porous, allowing some small amounts of air in and out. Winemakers usually fill barrels to the brim to start. Sometimes they top them up and sometimes they don’t.

BARREL AND PARTS

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

At a wine tasting, the winemaker said he used oak chips in the wine. I was too embarrassed to ask what he meant.

Diagnosis: With a little onion dip, they’re delicious. Otherwise, this winemaking tool is an extremely inexpensive alternative to using barrels. Like barrels, oak chips can come from Europe or America, and the size, age, and degree of toast play a part in the wood complexity they add. They are most effective when used like a tea bag during fermentation, as the heat that is produced extracts maximum flavour. Occasionally, the wine can become so oaky that it may have to be back-blended with some unoaked wine to soften the blow. This method of adding wood complexity to a wine is not overly popular.

Using oak chips really does detract from the whole “mystique” of barrel-ageing. I’m actually surprised this winemaker admitted using them. Since it is not considered “chi chi,” most are not likely to confess to it, and you’ll never see it mentioned on the label. Besides, oak chips produce volatile acids in wine, reducing its ageing ability. How can you tell if they have been used? A wine description that mentions “oak influence” or “oak maturation” on the label, without actually stating any form of barrel, is usually a good clue to their use.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

Can oak from anywhere in the world be used for wine?

Diagnosis: Oak trees are indigenous to the temperate northern hemisphere. It would seem to make sense to use whatever is convenient. However, this isn’t the case.

The best oak for wine tends to come from America and Europe.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

What’s the main difference in flavours that American and European oak add to wine?

Diagnosis: European oak can be tight and wide-grained, and adds smoother, subtler flavours to wine. American oak, on the other hand, is more aggressive, adding many upfront flavours like vanilla and spice and textures like astringency. It tends to be looser grained, as a rule. American oak seems to be used more for red wines than white.

Where in Europe and America does most oak used for wine originate?

Diagnosis: The European oak most favoured by winemakers, worldwide, comes from France and is usually air-dried. The interesting thing about French oak is that the many forests throughout the country provide oak that adds slightly different flavours to the finished wine. Some oak is also used from the Balkan area, such as what used to be Yugoslavia. Often used for large casks and vats, this oak tends to be more tannic or sappy, and sometimes just plain neutral. Portugal does provide a small amount of oak. It’s subtler than locally used chestnut and cheaper than French oak. The best American oak hails from Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Wisconsin, and Arkansas.

Oak barrels are not cheap. If French oak is your thing, be prepared to dish out anywhere from $700 to $900 apiece for a new 225-litre barrel. The American counterpart costs less, at approximately $300 to $500 apiece. It’s no wonder wine aged in oak, especially French oak, is expensive. If you are thinking about getting into the forestry business, grow oak trees.

COMMON BARREL NAMES, SIZES, AND WHERE USED

| NAME | SIZE | WINES /REGIONS /COUNTRIES |

| Foudre | Varies | Alsace, France |

| Pièce | 216 litres | Beaujolais, France |

| 228 litres | Burgundy, France | |

| 205 litres | Champagne, France | |

| 220 litres | Anjou/Layon/Saumur, France | |

| 225 litres | Vouvray, France | |

| 215 litres | Maçonnais, France | |

| Barrique | 225 litres | Bordeaux, France |

| Rhône, France | ||

| Fuder | 1,000 litres | Mosel, Germany |

| NAME | SIZE | WINES /REGIONS /COUNTRIES |

| Stück | 1,200 litres | Rhine, Germany |

| Pipe | 560 to 630 litres | Port, Portugal |

| (534.2 for shipping) | ||

| 418 litres | Madeira, Portugal | |

| Butt | 490.7 litres | Sherry, Spain |

| Gönci | 136 litres | Tokay, Hungary |

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

How many different types of oak come out of France?

Diagnosis: French oak is usually designated by the forest it was grown in, and there are a number of them. The western Loire and Sarthe produce tight-grained, excellent-quality oak. The Limousin forest delivers wide-grained oak. The forests of Never, Allier, Tronçais, Vosges, Jura, Bourgogne, and Argonne all supply tight-grained oak.

It is through trial and error that most winemakers come to a decision as to which forest provides the best French oak for their particular product. This is definitely a case of your not seeing the forest for the trees. For instance, Limousin oak is used exclusively for brandy, especially cognac. Never, Allier, and Tronçais are used for wine and brandy. Vosges is used for wine, while Jura and Bourgogne are used for Burgundy. Argonne is widely used in Champagne.

Dear Dr. WineKnow:

What countries utilize American oak barrels?

Diagnosis: Spain is a large advocate of American oak. Although they have laid back a bit with overall oak usage, American still remains the oak of choice. It’s no surprise that the United States uses a lot of it. Canada uses a fair bit, especially for red wine. South America seems to like it, too, as does Australia.

Perhaps it has something to do with the heat factor. An overview would suggest that warm viticultural areas in the world like Spain, California, Chile, Argentina, and Australia favour or use a lot of American oak. Riper, more powerful wines are produced there, which can handle the attack of this oak better than cool-climate wines. If you are not a big fan of these regions’ wines, it could be because of the choice of oak treatment. You may want to seek out wines from these areas that utilize French oak.