5

Conflict and compromise: into the twenty-first century

The present generation is witnessing the most comprehensive and far-reaching changes of the natural history and historical landscape of Britain ever experienced in such a short period of time.1

From the 1960s the perception of what conservation in the countryside meant gradually changed. Sometimes described as the ‘democratisation of the countryside’, this has been to a great extent the result of an increasing awareness among the population in general, rather than just a minority of the professional and leisured classes, of the huge value of the natural and cultural heritage and of the varied landscape in which we live. Increased leisure time, along with the availability of transport, has all been part of this process. Gradually the word ‘preservation’, suggesting a static situation of ring-fenced specific historic sites or ecologically sensitive areas, was replaced by ‘conservation’, allowing for wider landscapes to be recognised and a realisation that by sensitive management different uses could co-exist.

While the early naturalists were concerned with the protection of particular species rather than their habitat, and the antiquarians with the finds from their excavations rather than the sites themselves, by the end of the nineteenth century these attitudes were beginning to change. Wildlife could only flourish if the environment was right, and the monuments as well as their contents were of value. From the 1950s these ideas were also expanded by an understanding that wildlife could often not survive within the tight boundaries of reserves: wider corridors linking these protected areas were also needed. In the same way, the setting of ancient monuments needed protecting if they were to be fully understood within their landscape.

Not only have our ideas of what conservation really means shifted over this period, but we can distinguish four elements in the development of the conservation movement, all of which are well illustrated by the conflicts and compromises in the Norfolk countryside. These four strands include nature and wildlife, rural landscape, archaeological remains and historic buildings. While these themes often overlap, the experience of Norfolk reveals differences in the level of public and political interest, in financial support from government, in the role of the voluntary sector, in the relevant institutional frameworks and in legislative powers.

Nature and wildlife: agriculture and conservation

For the first time a clash between agriculture and conservation began to emerge, largely as a result of increased public awareness of the damage modern farming caused to wildlife and the visual landscape. The war-time Scott Committee had seen the existence of a well-farmed and prosperous landscape as the key to a vibrant and diverse countryside well managed for the benefit of man and nature. ‘There is a community of interests between agriculture and amenity.’ The threats, as Scott saw them, were from new building, mainly in the form of ribbon development, and poorly sited industry. The best way of protecting the countryside was to retain the existing area of farming and limit the encroachment of development into and within the countryside. Farmers were its best custodians.2 However, as the horse disappeared from farms in the 1950s, to be replaced by ever-more powerful diesel tractors which needed ever larger fields in which to operate, and chemicals came to play an even greater part in farming practice in the form of fertilisers, herbicides and insecticides, agriculture came to be seen more as a threat to, rather than a protector, of the countryside. Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, published in 1963, highlighted the dangers of the well-known insecticide DDT (chlorinated hydrocarbon) entering the food chain of many birds and proved to be the moment when the dangers of modern farming to the environment hit home to the public. Science and technology, which had been so generously funded by business and government, became increasingly associated with pollution and the destruction of habitats and diversity. These points were again brought home in Nan Fairbrother’s seminal book New Lives, New Landscapes, published in 1970. Howard Newby dates the moment at which farmers changed from being seen as protectors to enemies of the countryside to 1973 and a speech given by the urban planner Sir Colin Buchanan to the CPRE. He described farmers as ‘the most ruthless section of the business community’ and ‘a real danger to the countryside’.3

At the same time as the ecological threats to the countryside were being recognised, the infant subject of landscape history was gaining recognition. W.G. Hoskins’ trail-blazing book The Making of the English Landscape, published in 1955, influenced a whole generation of historians and archaeologists. It led to the recognition of the diverse and now fast-changing landscape and its buildings as a source of history. This was followed in 1986 by the botanist Oliver Rackham’s History of the Countryside, which stressed the importance of trees and hedgerows to an understanding of the landscape.

As farming changed and employment in agriculture declined, the farming industry came in for more and more criticism. The destruction, often with the encouragement of government subsidies, of archaeological sites and natural habitats by the ploughing-up and drainage of old grasslands and the use of more powerful machinery, as well as the grubbing up of hedges, became an evergreater threat. Between 1946 and 1981 58 per cent of Norfolk’s hedgerows were removed. Fifty per cent of ancient, semi-natural woodland remaining in 1945 had gone by 1973, 73 per cent of the 1946 grassland had been ploughed up and only 7 per cent of the remaining was herb-rich unimproved land and heathland. Old pits, often dug in the nineteenth century for marl, were filled in, thus reducing the diversity of wildlife habitats.4 Archaeological earthwork sites, too, were being bulldozed, deep-ploughed and sub-soiled. Once the statutory threemonth advance notice for destruction of a scheduled site had been given no further permission was needed. The effects of more intensified farming were recognised by 1954, when the number of inspectors employed by the Ministry of Works was increased with the aim of scheduling more grassland sites. In 1968 the Walsh Committee was set up to review the importance of field monuments on amenity and archaeological grounds alongside a government enquiry into the effects of plough damage on archaeological monuments. As a result of their findings local authorities were urged to do more to protect their monuments. This resulted in a Field Monuments Act of 1972, which introduced the concept of Acknowledgement Payments to farmers, who agreed to keep monuments out of cultivation. However, the payments were too small to be effective. By the mid 1970s it was recognised that earthwork sites were disappearing rapidly and that the level of the Acknowledgement Payment provided no incentive to protect them. The annual payment was £35, while the loss of income from not ploughing was nearer £95. When the barrows of Norfolk were surveyed in the 1930s almost all were in good condition, while in the 1970s fifty-three of the 162 scheduled barrows were being ploughed and only thirteen were more than fifty cms high.5 An important change came with the 1979 Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act, which required landowners to apply for formal consent (rather than just give notice) before undertaking any works that would affect a Scheduled Ancient Monument. If the land was already ploughed this included any work liable to disturb the soil below the maximum depth affected by normal ploughing. The Acknowledgement Payment scheme was ended and instead, under Section 17 of the Act, English Heritage could make grants to farmers and landowners for good conservation management of scheduled and other monuments of schedulable quality, including taking sites out of arable use.

It was not only farming that was seen as a threat. Michael Dower’s The fourth wave: the challenge of leisure (1965) listed the events over the previous 200 years which had challenged the environment. First was the industrial Revolution and its coal-fired factories in mushrooming industrial towns, and then there were the railways. Thirdly, there were car-based suburbs and finally, in the second half of the twentieth century, there was an increasing demand for outdoor recreation. A desire to enjoy open spaces and natural scenery which could now be satisfied by a far larger proportion of the population than previously was in danger of destroying the very sources of that pleasure. In the Norfolk Broads, for example, the first comprehensive plan for the area identified two principal problems: the conflict between the expansion of holiday and recreational activities and the natural character of Broadland; and the conflicting demands of the various recreational uses for a limited amount of water space.6

39 The Broads Wildlife Centre at Ranworth was opened by the Norfolk Wildlife Trust in 1976. This floating centre provides an opportunity for the interpretation of the whole Broads area.

40 The silent and environmentally friendly Broads Authority ‘electric eel’, moored at How Hill and ready to take groups out.

From the mid-1960s Norfolk experienced a rapid increase in the rate of population growth. This reflected expansion of employment in the towns, retirement migration, mainly from the south-east, and London overspill schemes in Kings Lynn and Thetford under the Town Development Act of 1952. During the 1970s and 1980s this acceleration in the county’s overall population was associated with a dispersal of new housing into the countryside. Despite county planning policies that aimed to focus much new development into selected settlements, the result of such pressures has been to ‘suburbanise’ the character of many expanded villages as well as the fringes of market towns.7 The impact of widespread housing estates and smaller-scale infill development in villages, together with the growth of tourism and the intensification of farming, were threats very much at the heart of the challenges facing conservationists in Norfolk.

Attitudes to visitors changed dramatically from the 1960s. The inter-war period had seen the development of a general suspicion of the ‘uneducated’ urban working class and their approach to the countryside. These were the people who broke fences, left litter and gates open, picked wild flowers rather than admiring them in their natural habitat, frightened birds and scrawled graffiti on historic buildings.8 This attitude is clearly illustrated in the case of Wretham Heath, 368 acres of which had been owned by the NNT since 1938. The rapid expansion of nearby Thetford to accommodate London overspill was seen by some as a threat to the undisturbed nature of this Breckland reserve. Dogwalkers from neighbouring Attleborough wrote letters to the Eastern Daily Press complaining about ex-Londoners who left litter. Ted Ellis, in his weekly article ‘in the Countryside’ of 22 May 1970, wrote that Wretham Heath should be treated as ‘a priceless heritage rather than a mere open space for every kind of frolic’. It was a nature reserve designed for people who wanted to learn more about nature and to do so in peace.9 The problem was how to manage such sites for public enjoyment while at the same time ensuring nature conservation, educational use and scientific study. The NNT’s solution in the case of Wretham was the creation of a Nature Trail guiding the public, with the help of a leaflet, on a marked route through the various landscapes of Breckland, thus leaving areas of the reserve undisturbed. That the NNT were able successfully to balance these needs was indicated by the support the Trust received from the public, as shown by its membership figures. While growing steadily in the 1950s to 900, in 1962 numbers suddenly shot up to 4,104 by 1972 and to 7,170 over the next decade, reaching 35,000 by 2012.

The 1960s saw similar conservation and educational work on the Broadland reserves. Up until then, apart from Hickling, where the head keeper would, by appointment, take up to four birdwatchers on a conducted tour, no reserve provided any guidance to either ornithologists or less specialist visitors. From 1963 a wide range of facilities began to be developed at Hickling by the NNT. Shallow lagoons and scrapes to attract waterfowl were created and new and larger hides built. In 1968 a thatched observation room was built and used as a base for the various self-guided walks and in 1970 a water-trail allowing visitors to see the banks of the broad from a boat was introduced. By the 1980s Hickling was attracting over 2,000 visitors a year. But the NNT wanted not only to introduce visitors to the delights of its individual reserves but, in the case of Broadland, to focus attention on the growing environmental problems resulting in part from changing agricultural practices. In 1976 the award-winning Ranworth Conservation Centre (now called the Broads Wildlife Centre) was opened. This floating building was erected on Swamp Carr, at the junction of Ranworth and Malthouse Broads, and could be approached by both land and water. The 500-metre walkway, bordered by descriptive panels, allowed visitors to see the changing flora from the oak woodlands of dry land to the reeds of the marsh at the broad’s edge. Similar interpretive work and visitor facilities such as hides and leaflets were provided by the RSPB and the Nature Conservancy at other sites across Broadland.10

The importance of education had long been recognised by the National Trust at Blakeney Point and Scolt Head. As well as the field trips for university students from London and Cambridge, the post-war wardens Billy Eales and his son, Ted, introduced thousands of Norfolk children to the delights of the Point. These school excursions were part of the educational programme formulated by an advisory group under the chairmanship of Dr White of university College, London.11

It was not until the 1970s that the RSPB became involved in the acquisition of important sites in Norfolk. The first of these were the north Norfolk reserve at Titchwell and the Wash coast site at Snettisham, both in 1972. Two Broadland sites at Strumpshaw and Surlingham were added in 1975 and the Berney marshes ten years later. Finally, in 2006, Sutton Fen in the Broads was purchased.

The Broads Authority, too, has supported education facilities at How Hill with information panels at the staithe, a small museum in an eel-catcher’s house and an electrically powered boat that takes visitors out on the river.

The importance of this increased interest in the countryside has also been appreciated by the Forestry Commission, who now see income from visitors forming a significant part of their business. Thetford Forest has an increasingly

varied landscape as areas of conifer plantation give way to heathland, allowing for the natural regeneration of native species. Belts of beeches which were part of the original planting to provide fire breaks are now reaching maturity and visitors are encouraged to walk, cycle and visit historic sites within the forest. Access is open and free, but High Lodge is being developed as an increasingly popular visitor centre.

While much attention has been focused on the Broads, Breckland, the north Norfolk coast and the Wash, changes in farming across the county as a whole have been of great concern to conservationists. A particular issue has been the destruction of hedgerows and the infilling of marl pits. The brief for the Countryside Commission’s New Agricultural Landscapes, published in 1972, had been to find out ‘how agricultural improvement can be carried out efficiently but in such a way as to create new landscapes no less interesting than those destroyed in the process’. It revealed ‘fresh and disturbing facts about the nature of change taking place’, including the level of hedge destruction and the removal of field boundary trees, 90 per cent of which had gone since 1945. Wildlife habitats, too, were being destroyed by intensive farming. The creation of nature reserves and national parks was not enough. A balance between protection and productive use of the countryside as a whole needed to be found. The industrialisation of farming, rather than urbanisation, came to be seen as the greater threat to the appearance, wildlife and recreational value of the countryside.12 Marion Shoard’s book The Theft of the Countryside (1971) took up the themes of Nan Fairbrother and introduced the idea that farmers should be subjected to the same planning laws as everyone else. This view was promoted by the CPRE (of which Marion Shoard was secretary) in their report Landscape: the need for a public voice (1975). Farmers should be required to inform the local planning authority of their intention to remove hedges or plough up open heath. It also pressed for a package of tax relief to compensate for the loss of productivity that might result.

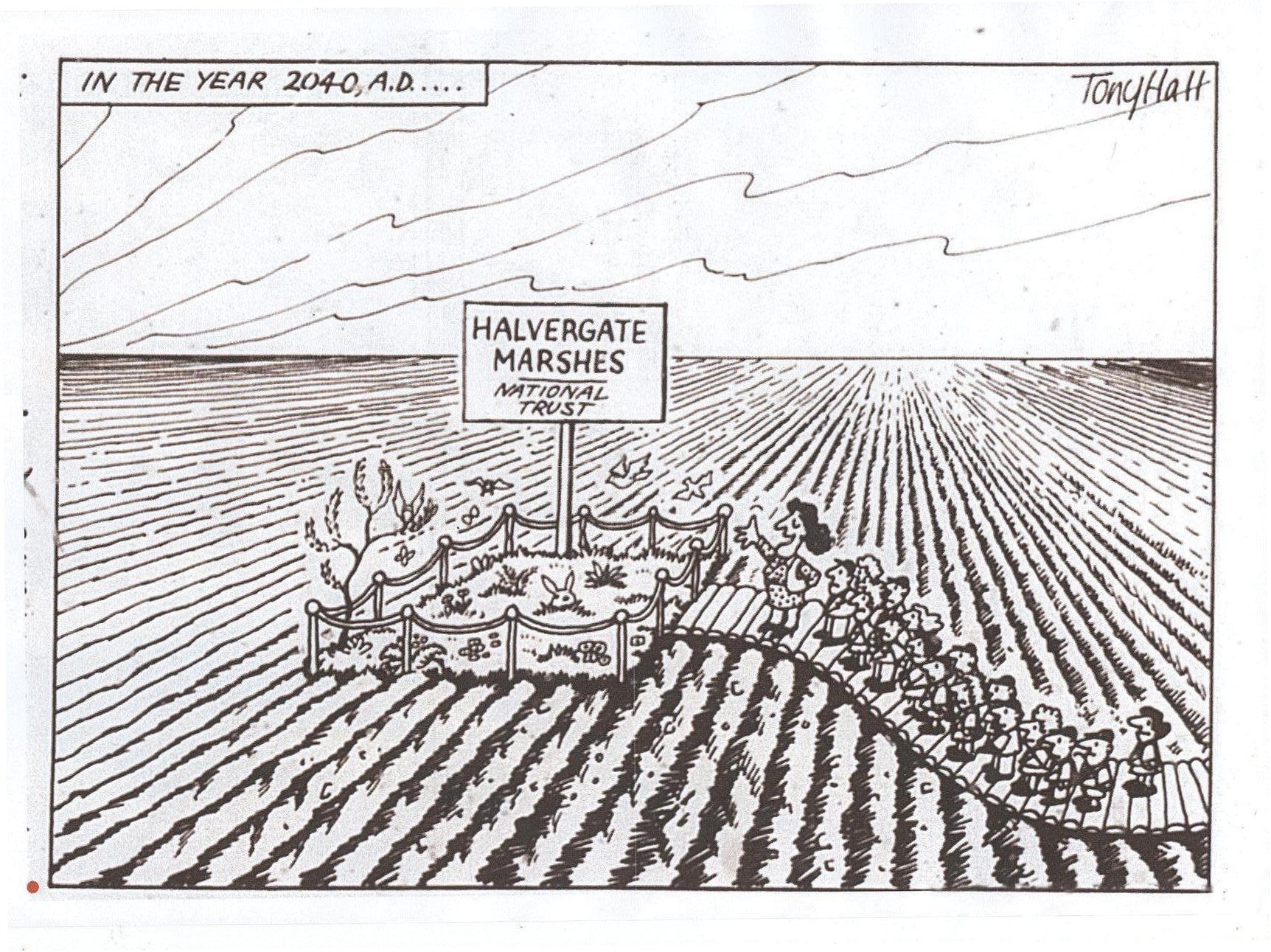

As always, it is only as the things we value begin to disappear that their importance is appreciated. It has already been shown how, encouraged by government subsidies, the 1960s saw the rapid increase in the intensification of farming and, with it, increasing publicity given to the damage to the rural environment. The response in the early 1970s saw these concerns being expressed in various ways in publications and particularly through the CPRE. The decade began with the European Year of the Environment and, in the uK, the creation of the Department of the Environment (DoE). In 1973 the Nature Conservancy was replaced by the Nature Conservancy Council (NCC) as a grant-aided body within the DoE. The decade also saw the beginnings of more militant movements attracting younger, more vociferous voices. Greenpeace was founded in 1970 and Friends of the Earth in 1971 with a membership of about 1,000. Ten years later membership of Friends of the Earth had risen to 27,000 and there were 200 active local groups. The Norfolk branch was frequently in evidence as the debates over the future of the Halvergate marshes grew more heated (see below). The Green Party was founded in 1973 and by the general election of 1989 received 15 per cent of the vote. Membership of such organisations as the National Trust, the NNT (now renamed the Norfolk Wildlife Trust (NWT)) and the RSPB also rose — in the case of the RSPB, from 10,500 in 1960 to 180,000 in 1974.13 By 1995 10 per cent of the population belonged to an environmental group.

In 1973 the government set up the Countryside Review Committee to review the state of the countryside and the pressures upon it. In 1976 it produced a discussion paper, The countryside: problems and policies, which addressed the potential conflict between increasing food production and conservation. In 1977 a joint response from the National Farmers’ union (NFu) and Country Landowners’ Association (CLA) was published with the title Caring for the Countryside, which gave practical advice on how farmers could combine food production with conservation.

One result of the growing realisation of the dangers of modern farming to a fragile ecological system, and particularly the need to safeguard wildlife habitats, was the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981, which heralded what John Sheail called ‘the decade when it all happened’14 — culminating, in 1987, with the publication of the Brundtland Report, Our common future, disseminating for the first time the concept of ‘sustainable development’. The fact that the passing of the 1981 Act and the number of amendments tabled along the way was such a drawn-out process is an indication of how far the establishment still lagged behind public opinion. The scale of the vested interests of farmers and landowners, as well as a government which did not want to have to foot the bill for substantial compensation payments for farmers’ loss of income for farming less intensively, was pitted against the conservationists. The bill is still the most

41 The Friends of the Earth, under the local leadership of Andrew Lees, played an important role in ensuring the survival of the Halvergate marshes. Andrew later died while working in the Madagascan rain forest, but his significance for Halvergate is recorded in this stone at Wickhampton church.

A cartoon by Tony Hall in the Eastern Daily Press on 15 June 1984 with the caption ‘Let us pause children, to remember that gallant band of conservationists who fought on your behalf to preserve all this.’

important piece of wildlife conservation legislation and it protects native species, including birds (and their nests and eggs), plants and animals, controls the release of non-native species, requires local authorities to compile maps of rights of way and gives greater protection for Sites of Special Scientific interest (SSSis). Importantly, it gave public authorities such as the recently established Broads Authority the right to negotiate management agreements with local farmers. The problem was that the cost of any such agreements had to be paid for by the Authority and not the government (Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF)).

42 The demise of a drainage dyke near Tunstall Bridge, looking north-east towards the River Bure and Old Hall drainage mill. This traditional scene, from 1976, shows the grazed marsh with dyke sides well cropped by cattle. A few years later the wooden fence had been replaced by a metal one. By the early 1980s the field was arable and the dyke clogged with weeds now that the sides were no longer grazed. Finally, in the late 1980s, the ditch was filled in.

International concern over the drainage of wetlands resulted in the Ramsar Convention, agreed in iraq in 1971, by which wetlands of international significance were awarded special status. The first to be designated in Norfolk was the Ouse Washes in 1976, followed by Roydon Common in 1993, Breydon Water in 1996 and, more recently, Dersingham Bog, the north Norfolk coast, Broadland, and Redgrave and South Lopham fen. The draining of wetlands was becoming increasingly possible with new machinery, corrugated PVC piping for underdrainage and more powerful Archimedes screw-type pumps. This work was usually grant-aided by the Ministry of Agriculture and the impact of these advances was felt particularly on the broadland marshes. The only tool available in the 1970s to protect the area was the designation of the most significant sites as national nature reserves (NNRs) or Sites of Special Scientific interest (SSSis), and, as a result of pressure from the Broads Authority, the area of these rose from about 120 to 180 hectares between 1972 and 1981.15 However, in many ways it was the large sweeps of the marshes that made them so significant in ecological and landscape terms and for these there could be little protection. The earliest large-scale drainage project in the Broads took place in the late 1970s and covered nearly 1,000 hectares to the south of the River Bure. The cost was over £400,000, which was mostly covered by grants, and the results allowed old grazing marshes to grow wheat and sugar beet. This intensity of arable farming not only removed wildlife habitats but also required the application of high levels of nitrogen, which soon seeped into the waterways, thus polluting them. The consequences for the landscape and ecology of the Bure valley were devastating, and fears for other areas of high amenity value were soon aroused. As a leader in the Eastern Daily Press put it in 1981:

The history of the Broads over the last sixty years or so has been one of conflict — between exploitation and conservation — between urban and rural values — between various leisure groups — but perhaps above all, between those who want water and those who want rid of it. The lowering of the water table regardless of ecological changes resulting, continues almost inexorably, even it seems, under its latest guardians.16

As public concern mounted, the Broads Authority published a report in 1982 entitled What Future for the Broads? This graphically explained the consequences, in both landscape and ecological terms, of the drainage of grazing marshes and their conversion to arable.

Plans for other drainage schemes were soon put forward covering 3,635 hectares between the Rivers Yare and Bure, an area recognised by the Broads Authority as being ‘probably the most important nationally, and also the most sensitive to change’.17 It was the last remaining stretch of open grazing marsh in eastern England, ‘wild, open, devoid of settlement and its varied ecology consisting of drainage dykes containing a fascinating variety of water plants, dragon flies and water beetles’.18 For the first time the Broads Authority was in direct confrontation with farming interests and a rift appeared between some Authority members, often representing local farming and commercial interests, and their senior advisors, including their conservation officer, who regarded the damage to the distinctive character of the area as unacceptable. After some dithering and much lobbying by the CPRE and Friends of the Earth, the Authority resolved in February 1981 that the drainage scheme should be opposed and that negotiations with the local farmers and drainage boards on ways to keep the grazing marshes should continue. Meanwhile, Friends of the Earth kept up the pressure. In 1984 the debate moved to the national stage with a series of letters to The Times. The Norfolk landowner and Labour spokesman on conservation Lord Melchett initiated the correspondence with a letter on 6 February 1984 condemning hedge removal. The cause was taken up by Lord Buxton and Lord Onslow in a letter describing the Halvergate marshes as ‘the largest remaining block of open marsh grazing landscape in England’. Their letter also pointed out the absurdity of paying farmers to drain and then compensating them not to drain.19 Archaeologists, too, took up the cause, with Dr Martin Bell of Lampeter university highlighting the destruction of the historic countryside and the monuments within it. In a far-sighted contribution to the debate he called for an integrated approach to conservation and for protection for landscapes rather than individual monuments.20 Lord Melchett expanded his views later in the year in a letter to the Eastern Daily Press calling for planning controls on change of use from pasture to arable on land that had not been ploughed for sixty years.21

43 A view across the Halvergate Marshes with Berney Arms windmill in the foreground and Breydon Water in the distance. The marshes represent the largest area of grazing marshes in England outside Somerset.

In July 1984, in direct action supported by Lord Melchett, thirty people surrounded diggers and bulldozers in a quiet demonstration in Moulton St Mary, where drainage was planned on ninety acres of marsh. A letter was sent to the Prime Minister, Mrs Thatcher, asking that agricultural developments should be subject to planning control and that further deep drainage in marshland should be put on hold.22 Further protests took place in Ludham and at St Benet’s Abbey.23 Members of the local branch of Friends of the Earth, under the leadership of Andrew Lees (later to lose his life while working for Friends of the Earth in the Madagascan rain forest), played an important role in keeping a look-out for any new drainage works. Twice they informed the Broads Authority of work about which they had not been notified. The Eastern Daily Press praised them for pursuing their objectives ‘in the most direct and peaceful manner.’24 The passing of the Wildlife and Countryside Act in 1981 allowed the Broads Authority to embark on an innovative experiment. By invoking Section 41 of the Act, the Authority required farmers to inform it of the intention to change grassland to arable. It was then up to the Authority to negotiate an agreement. As a result, the Broads Grazing Marshes Conservation Scheme was launched in 1985, which encouraged farmers in a tightly defined area enclosing the most sensitive grazing marshes around Halvergate to enter into management agreements to demonstrate how livestock farming and landscape preservation could work together. Subsidies of £50 a hectare were offered to participating farmers and a government grant was available to help underpin the scheme for three years. Farmers within the scheme were required to keep stocking rates low and consult the Authority before removing landscape or archaeological features, erecting buildings, constructing roads, underdraining, levelling or direct seeding the land and applying herbicides or anything but low levels of nitrogen. Here, for the first time nationally, we see farmers and conservationists working together to protect a unique landscape. It provided the model for the government’s Environmentally Sensitive Areas (ESAs), introduced in the Agriculture Act of 1986, which accepted a statutory duty ‘to achieve a reasonable balance between the promotion and maintenance of a stable and efficient agricultural industry and the conservation, amenity enhancement, wildlife, historic interest, public enjoyment, social and economic interests of the countryside’.25 It allowed the government for the first time to channel agricultural money into conservation. The Broads were one of the first five ESAs to be established in England, with the scheme coming into operation in March 1986. This was a triumph for conservation, largely pioneered, often against much opposition, by the Broads Authority. It was immediately popular and has resulted in the inclusion by 2011 of 43,000 hectares of the grazing marshes, with their diverse and important wildlife and landscape remaining under traditional farming. Since 1985 the number of ESAs within the county has expanded to include the upper valleys of the Wensum and Bure and areas of Breckland. Alongside ESAs, Countryside Stewardship Schemes were introduced in 1991 to protect other farmland of environmental significance. The two separate schemes are now (2014) being gradually phased out and replaced by Higher Level Stewardship schemes to protect farmland of wildlife and historic importance.

While these voluntary agreements form an essential part of conservation in Broadland and elsewhere, closely monitored and protected areas remains important. As farmers came to realise that the ploughing up of the marsh was not likely to be acceptable they began, in some cases, to put land up for sale, and in 1986 the RSPB bought land in the Halvergate marshes from the Berney estate and the Berney Marshes Nature Reserve was established. Its holding has since been increased to 1,000 acres. Water levels are carefully managed by blocking off the end of ditches to stop the water running off the reserves, while traditional windmills stop the water levels rising too high. As a result the number of breeding wading birds has increased, peaking at 324 pairs in 2008, while the number of wintering wildfowl on the marshes and neighbouring Breydon Water has also gone up dramatically. The RSPB also works with neighbouring farmers so that an area covering 6,000 acres is farmed in order to provide an extended habitat for waders.

As well as the highly publicised conflicts, more considered discussions were under way. It was clear that a multi-use principle had to be established whereby, on land that was not designated as of special interest or value, concessions were still made to the natural and cultural environment. While designated areas are essential for providing habitats for rare species, the more common ones need protecting in the wider countryside. Specialist conservation was required on protected sites, while, elsewhere, farmers and landowners could complement them in supporting more common species, which also form essential parts of the eco-system. The late 1960s saw exercises at the Farmers’ Weekly farm at Tring to discover practical ways of combining conservation with profitable farming. This led to the founding of the first Farming and Wildlife Advisory Group (FWAG). At first this was little more than a national talking shop for the main organisations involved with the management of land, with MAFF acting as the secretariat, but this soon developed, with the founding of local FWAGs at county level. In 1983 a meeting was held at Sennowe Hall in Norfolk, hosted by the then chairman of the NWT and attended by the Duchess of Kent, to which landowners, farmers and other potential benefactors were invited. The aim was to consider how to start a local FWAG and to fund a Norfolk FWAG adviser. This resulted in the setting up of a system of part-time voluntary advisers from the RSPB, the Agricultural Development Advisory Service (ADAS) and the County Council ecologist working with local farmers. The national Farming and Wildlife Trust was founded in 1984 and supported by MAFF, ADAS and the NFu, as well as a membership of farmers. This enabled the funding of local advisors and the first fulltime FWAG adviser funded by MAFF and ADAS was appointed to work alongside the volunteers.26 Soon there were sixty-two county FWAGs with over thirty fulltime advisors. As well as advising individual farmers they ran seminars and organised farm walks (the first in Norfolk, soon after the appointment of the full-time adviser, was to Abbots Farm, Stoke Holy Cross) which provided useful meeting places for like-minded individuals. From being a talking shop, FWAG became a co-operative agency for promoting good conservation practice on working farms.27

44 Emily Swan of Natural England speaking about rare flowering plants growing in arable fields on a FWAG walk at Peewit Farm, Briston, in July 2010.

More recently it has been positive steps to restore diversity that have been of increasing importance. For instance, the water of many of the Broads, such as Barton Broad, has been invaded by algae, mainly as a result of the enrichment of the water by phosphates and nitrates. The algae have blocked out sunlight, causing many plants to die and sink to the bottom, forming a thick muddy deposit. However, programmes of dredging have pumped out huge quantities of sludge and encouraged the return of waterfleas, which eat algae, and so the water has become clear again, resulting in a return of a diversity of animal and plant life.

Archaeological remains

So far concern over the destruction of natural habitats and diversity had been the major concern. However, not only were habitats in the farmed landscape under threat but so was the archaeology. Realisation of the pressures modern farming put on archaeology led the government to set up the Walsh Committee to report on the management of field monuments, the findings of which were published in 1969.28 The report made several important recommendations including the appointment of Field Monument Wardens to conduct regular inspections and the compiling of local records of monuments for the information of local planning authorities. The damage done by ploughing, the flattening of earthworks and the grubbing up of woodland was soon appreciated as a real danger. In 1971 (the same year as the founding of Friends of the Earth) archaeologists, spurred on initially by the destruction of urban sites under new development, founded Rescue.

One of the stated aims of Rescue was to encourage the creation of the post of County Archaeologist. The Norfolk Archaeological unit, founded in 1973 and taken over by the County Council in 1978, was run by the County Archaeologist within the county Museum Service. It was the first such county-based unit to be formed in Britain, responding to one of the recommendation of the Walsh Committee. It built on previous records kept by the museum to create a County Sites and Monuments Record (SMR). The unit was responsible for initiating several county surveys of monuments which were a necessary precursor to evaluating monuments to be recommended for protection. These reports were published in a new series, entitled East Anglian Archaeology, launched by Norfolk and Suffolk County Councils in 1975. These included surveys of barrows in East Anglia (1981), ruined and disused churches of Norfolk (1991) and earthworks in Norfolk (2003). The barrow survey was the first comprehensive survey of a particular class of monument in the country, resulting in the scheduling of all Norfolk’s well-preserved examples. While the survey of all earthworks in grassland in the county did not result in newly identified sites receiving statutory protection it is regularly referred to by farmers and their advisors to ensure sites are recognised in ESAs and other Stewardship schemes. The ruined churches survey provided a useful catalogue of surviving ruins in a county that has more such sites than any other in England. At the same time, new sites were being identified by air photography. For instance, while 196 flattened Bronze Age burial mounds had been recorded by 1974, air photography resulted in 712 new ones being located by 1986. By 1987, the Archaeological unit air photograph library held over 21,500 photographs.29

A report by English Heritage in 1995 entitled The Monuments at Risk Survey (MARS) pointed to the destruction caused by modern farming. Nationally, for the period 1945–1995, the percentage of earthwork monuments with very good survival had fallen by 20 per cent, and other figures were equally dramatic. Although these figures cover England as a whole, it was in the arable east that destruction was greatest.30

‘Preservation by record’

Some of the greatest threats to archaeology came from urban regeneration and here the only possibility was to excavate and record before sites were destroyed (‘preservation by record’). Following a visit to Kings Lynn by the Society for Medieval Archaeology in 1962, 1963 saw the start of the Kings Lynn Survey. Largely supported by the Ministry of Works, a series of rescue excavations within the old town took place from 1963 to 1971. Alongside the excavations went a study of standing buildings and documentary work — a model example of coordinated research which has been published.31 This was followed by the Norwich Survey, funded by the Department of the Environment, Norwich City Council and Norfolk County Council and supported by the university of East Anglia. Between 1971 and 1978 thirty-eight sites were excavated, accompanied by architectural and documentary research. The aim was to ‘record and publish evidence for the origin and development of the city’.32

Encouraged by these heightened programmes of research, in March 1988 strong policies for conserving the county’s archaeology were introduced into Norfolk’s Structure Plan, which stated that ‘Development which would affect sites of outstanding archaeological importance will only be permitted in exceptional circumstances. On other sites of archaeological importance and where there is no overriding case for preservation, development will not normally be permitted unless agreement has been reached to provide for the recording and, where desirable, the excavation of such sites.’33 These two policies were a great leap forward and provided for the first time strong grounds for recommending the refusal of planning permission for archaeological reasons and for arguing the case for developer funding of excavations in the affected area in return for planning consent. The first excavation paid for in this way pre-dated the County Structure Plan by nearly ten years. In 1979 Anglia Television wished to extend their offices within the area of the north-east bailey of Norwich Castle, which was a Scheduled Ancient Monument. The 1979 Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act, which would have the power to prevent the destruction of a scheduled site, was then being discussed by parliament, and as a result tough negotiations took place and the company agreed to pay for the excavation. This excavation showed that before the area had been cleared by the Normans there had been a church with a large cemetery on the site. Long before the days of Time Team, this work received much television coverage and was described in a popular booklet, Digging under the Doorstep.34 In 1987 a further development within the Castle outer bailey was proposed — the Castle Mall shopping centre — and, again, the developer agreed to pay for excavation. The result was a large-scale excavation funded by the developer in 1987–1991.35 As with the Anglia Television site, a great effort was made to engage the public by providing a viewing platform and exhibition, while school parties were encouraged to visit.

A further cause of destruction of archaeological sites was road improvement. This included the proposed A140 Scole bypass, which ran through a Roman town, while a series of sites were threatened by the A47 Norwich southern bypass. In both cases the Department of Transport agreed to finance survey and, where necessary, excavations — and in both cases before the law required them to do so.36

Although already foreshadowed by statements in the Norfolk Structure Plan, 1990 saw an important national initiative for the protection of archaeological sites with the publication of Planning Policy Guidance 16 (PPG 16), ‘Archaeology and Planning’. This stated that ‘Where nationally important archaeological remains, whether scheduled or not, and their settings, are affected by proposed development, there should be a presumption in favour of their physical preservation.’ For the first time unscheduled sites could be protected as well as scheduled ones and, as with wildlife, there was the realisation that the drawing of tight boundaries around a protected area was not the way forward. The destruction of its setting could be equally damaging. PPG 16 also introduced nationally something already accepted in Norfolk: the concept of ‘preservation by record’, whereby, if the case for development outweighed that for preservation, then the planning authority could insist that the site was archaeologically recorded and a full record made at the expense of the developer before any new work was undertaken. The first brief issued by Norfolk Landscape Archaeology (the renamed Norfolk Archaeological unit) on behalf of the County Council was in March 1991. It required the developer of an area of housing in a field on the edge of Watton adjacent to a Roman road where there was evidence for Roman-British settlement to appoint an archaeological contractor to undertake a small excavation sampling 2 per cent of the area and produce a report of the findings.

Although this control of destruction as a result of development was a start, the reduction in the destruction caused by the ploughing up of grassland and gradual attrition of sites on arable land had to await the agri-environment schemes of the 1990s. Even today many archaeological sites of importance remain unscheduled and continue to be ploughed and subsoiled with no protection whatsoever.

The protection and care of churches

‘Norfolk is one of the architectural treasures of Europe because of its medieval country churches. Their profusion is their greatness.’37 So wrote John Betjeman in 2001 on the subject of a further area of concern, the future of some of Norfolk’s 659 medieval churches, many of them remote from their communities. In 1972 the Norfolk Society (the local branch of the CPRE), on behalf of their Committee for Country Churches, published Norfolk Country Churches and the Future. Edited by Lady Wilhemena Harrod (one of the authors of the Shell Guide), the foreword was written by John Betjeman. The Pastoral Measure of 1968 (‘one of the most complicated pieces of ecclesiastical legislation of recent years’38) allowed for the Diocesan Pastoral Committees to recommend to the Church Commissioners churches to be declared redundant. As a result, after consultation with the Redundant Churches Advisory Boards, some might be converted to other uses, while the most architecturally important could be taken over by the Redundant Churches Fund, who would be responsible for their repair and maintenance. By 1976 the Committee for Country Churches had become the Norfolk Churches Trust (the first such trust in the country), with Lady Harrod as its first chairman. Its aim was to prevent redundancies by encouraging interest in the county’s churches, declaring that ‘every church in the county is of value for its part in the life of the community, its effect on the landscape, and its interesting features’.39 From the beginning, the Trust organised church tours which usually attracted over a hundred people. The Trust encourages a membership and receives grants, particularly from the Government’s landfill Tax Credit Scheme, which enable it to give advice and financial help. Not only was the Trust a first for the country, but so was its annual sponsored cycle ride, in which participants cycle to as many churches as they can in one day. This usually raises over £100,000 and is an idea which had been taken up elsewhere. During the first twenty-five years of its work the Trust rescued twenty-five churches from closure after periods of disuse and decay, as well as grant-aiding essential repair work in many others.40

The protection and management of field monuments

As with wildlife, there was a need for a more positive approach to the protection of field monuments involving a joint approach between farmers and archaeologists. Under Section 17 of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act of 1979 grant-aided management agreements were made available to owners and occupiers of ancient monuments, and until 1990 these were always directly initiated by English Heritage and were mostly for scheduled monuments. However, there was a need to alert farmers to the valuable historical evidence on their land and to its fragility. In the late 1980s a booklet called ‘Farming on ancient monuments in Norfolk’ was published and distributed by ADAS. In 1990 a new project, The Norfolk Monuments Management Project (NMMP), was piloted in Norfolk, whereby the County Council’s Department of Planning and Transportation and the renamed Field Archaeology Division of the Museum Service took over from English Heritage the role of offering Section 17 grants. This initiative was the first of its kind in Britain and a NMMP officer was appointed by and reported to a committee chaired by the County Archaeologist and representing farming, wildlife and archaeological interests. An important feature of the early years was a six-monthly meeting of the committee, which would include a field visit. This helped all involved to understand the issues and it enthused them with a love of history and a wish to protect sites on farms. The work of the project officer involved arranging visits to farms where a field monument had been identified through previous survey. Unlike the practice under English Heritage, the scheme was promoted among farmers of unscheduled (but believed to be of schedulable quality) as well as scheduled sites. In this way awareness of the significance of sites was raised and many farmers were happy to enter into management agreements funded by English Heritage and to consult the NMMP officer on suitable farming methods to protect the monument. Links with FWAG have ensured an integrated approach to archaeology and wildlife.41

45 The demolition of a Norman house in Queen Street, Kings Lynn, in 1977 drew national attention to the lack of protection for many such buildings. Shown here are workmen chipping off the stucco.

45 The demolition of a Norman house in Queen Street, Kings Lynn, in 1977 drew national attention to the lack of protection for many such buildings. Shown here is to reveal two Norman windows.

45 The demolition of a Norman house in Queen Street, Kings Lynn, in 1977 drew national attention to the lack of protection for many such buildings. Shown here is the overnight demolition of the building.

The protection of historic buildings

The early 1970s saw concern over the inadequate coverage of the early lists of historic buildings, which had been very selective in the types of buildings covered. Very few built since 1830 were included, so many early industrial buildings, as well as victorian and twentieth-century buildings, were left unrecognised. The lack of descriptions also reduced the value of the early lists. Many buildings had also been missed and these sometimes came to light only when work on alteration or demolition began. In this case, emergency ‘spot-listing’ was possible to halt the work. Builders who suspected that spot-listing might be contemplated, however, could simply demolish before a notification came through. Nationally, the weekend demolition in 1980 of the Firestone building, a distinctive modernist building of the 1930s on the Great West Road in London, hit the headlines. Locally, a Norman house in Queens Street, Kings Lynn, previously unrecognised behind a stucco façade, was demolished over a weekend in 1977 when a spot-listing request was likely to be enforced on the Monday. Although the building was in a Conservation Area and early photographs showed the outline of Norman windows before the building was refaced, its importance had not been fully appreciated or researched before a public enquiry and permission for demolition had been granted.

46 The grade I sixteenth-century Waxham barn was compulsorily purchased by the Norfolk County Council to save it from collapse. With funding from a variety of sources it has been restored to its former glory.

As a result of such cases, a national resurvey to update the lists was begun by inspectors from the Ministry of Works. Progress was slow and by 1980 only towns and the former Rural District of Depwade in the south of the county had been covered. In 1980 Michael Heseltine, the then Minister for the Environment, realised that at this rate it would take centuries to complete the work and so introduced the ‘accelerated resurvey’. In Norfolk three new staff on three-year contracts were attached to the county conservation team to undertake the work. Descriptions were much more detailed and photographic slides of every building were taken, which are still held by the county’s planning department. While there were certainly some buildings that slipped through the net, particularly in the Depwade area, which had been re-covered in the 1970s, the resulting coverage led to an increased awareness of the great wealth of historic buildings in the county and its rich architectural heritage. The lists now cover 11,203 buildings, ranging from small structures such as lime kilns and pig sties to great houses such as Holkham Hall. Part iv of the 1968 Town and Country Planning Act had introduced both spot-listing, a vital defence against premature demolition, and the listed building consent procedure, which required planning authorities to consider application for demolition or alteration against a specific set of criteria. There should always be a presumption in favour of preservation unless there was a strong case for demolition. However, the fine for illegal demolition was less than £100, which was hardly a deterrent to an impatient developer. A Buildings at Risk Register is produced every year both locally, by the County Council, and nationally, by English Heritage, and includes all grade I and II* buildings that face particular threats from either unsuitable redevelopment or dereliction. In 1984 English Heritage, a government quango which took over the roles of the Historic Buildings Council and the Ancient Monuments Board and the responsibilities for the historic fabric which had been part of the Department of the Environment, was created. It became the statutory advisor to the Department of the Environment on such matters as listing and scheduling.

The county’s regularly updated Buildings at Risk Register was an important tool for conservationists, as was shown in the case of the gigantic grade I listed sixteenth-century barn at Waxham, which had become increasingly dilapidated since 1950. The great October gales of 1987 blew away much of what remained of its roof and the owner applied for consent to demolish, which was refused; when he failed to comply with a Repairs Notice the County Council acquired it by compulsory purchase. With funding from a variety of sources, repair work took place between 1991 and 1993 at a cost of just under £500,000. It now stands rethatched, weatherproof and repaired, and is a fine example of sixteenthcentury decorative brickwork within flint walling.

47 Foulsham Conservation Area: Foulsham was one of the earliest conservation areas to be designated (1979). As a result the historic core has retained much of its traditional character.

In the early 1990s the County Council produced a series of ‘Topic papers’ covering various types of buildings, such as ruined churches, drainage mills, corn mills and farm buildings. This resulted in thirteen ruined churches being repaired and consolidated between 1992 and 1997 with funds from the County Council and English Heritage. The most dramatic of these projects was the saving of the little church of Houghton-on-the-Hill, with its wealth of unique and beautiful wall paintings, the earliest dating from the late eleventh century.42

The protection of villages

With the exception of villages on the outskirts of Norwich, Great Yarmouth and Kings Lynn, the population of a total of 483 parishes fell by nearly 10,000 in the 1950s. By 1966 the number of villages in decline had reduced to 300. In 1968 the County Council received a report from the County Planning Officer entitled ‘The Dying village’.43 The disappearance of jobs in agriculture coupled with the closure of local railways and RAF bases led to the steady run-down of local services. At the same time the ability of townspeople to travel ever-further to work meant that during the 1960s villages were ceasing to be focused on farming, and instead becoming commuter communities. Older village properties were being bought up and there was often a rapid increase of modern housing around historic cores. Old sets of farm buildings became redundant and either fell into ruin or were converted, sometimes unsympathetically, into desirable ‘executive’ residences. The attractions of living in the countryside also appealed to those reaching retirement age. Selling an urban property and exchanging it for a new bungalow with a garden on the edge of an old village could be a financially attractive proposition. Pressure groups and local residents’ associations (frequently made up of incomers) sprang up to prevent the onrush of change. ‘Articulate and influential, the newcomers were able to ensure that local planning policies reflect[ed] their views.’44 The need to protect not only individual historic buildings but also whole neighbourhoods resulted in the concept of ‘conservation areas’, created under the Civic Amenities Act of 1967, which aimed ‘to make provision for the protection and improvement of buildings of agricultural or historic interest and of the character of areas of such interest’. It recognised the importance of preserving the harmony of whole areas rather than individual buildings in isolation. Pleasant groups of buildings together with open spaces, trees, historic street patterns and village greens were recognised as all contributing to the special character of an area. The act allowed local authorities, after consultation with local communities, to designate such areas where stricter planning controls would be implemented. However, the legislation lacked teeth and it was not until the Town and Country Amenities Act of 1974 that permission was required to demolish an unlisted building in a Conservation Area. Norfolk was slow to designate Conservation Areas but in 1971 a list of fifty-nine towns and villages for study and potential designation was drawn up, with Woodbastwick in the Broads to be the first to be designated. It was quickly followed by many more in both village and urban situations. In the 1980s and 1990s rural conservation areas began to be established, such as one in the Glaven valley and later the Halvergate marshes, and, even more recently, Coltishall RAF base. The mid-1970s also saw the first conservation officers to be appointed by district councils in Norfolk. The downside of this was that conservation could be seen as a negative movement, preventing progress and strangling the countryside. Indeed, although Conservation Areas often created a new awareness of and pride in the built environment within the community, in practice they could do little other than discourage the demolition of historic buildings in town and village centres.

In 1974 local government was reorganised and the County Council now had strategic planning and transportation responsibilities over the whole county. The statutory plan-making process started afresh, with a Norfolk Structure Plan approved in 1978. The new Districts were responsible for local planning decisions in line with the requirements of the Structure Plan and there was much more emphasis on environmental protection and building conservation.45

48 One of the first projects of the Norfolk Buildings Trust was the restoration of the two lodges designed by John Soane at the entrance to Langley Park, just outside Chedgrave.

The Norfolk County Council-sponsored Trusts

In the late 1970s it was apparent that many important Norfolk buildings of architectural and historic merit were becoming derelict, either because their owners refused to sell them or because prospective purchasers regarded them as uneconomic. To address this situation the County Council’s planning and transportation department initiated the creation of various trusts which would be in a position to attract outside funding. To coincide with European Architectural Heritage Year in 1975, the government established an Architectural Heritage Fund from which such trusts could borrow money at low interest rates to tackle repair projects that would otherwise be unviable.

The first such trust in Norfolk was the Norfolk Historic Buildings Trust, set up jointly by Norfolk County Council and the Norfolk Society. The Trust acquired its first property in 1978 and has since operated on the ‘revolving fund’ principle. However, where buildings could not be converted without losing their essential conservation value, they have been retained by the Trust. The Norfolk Windmills Trust was also established to help conserve the mills and pumps that are a distinctive feature of the county’s heritage. Such initiatives demonstrate the significant role of voluntary and charitable bodies, particularly when public sector resources are scarce, if the distinctiveness of the local environment is to be conserved. The 1970s saw the County Council increasingly involved with conservation of both buildings and landscapes. As well as supporting the Buildings and Windmill Trusts, its Planning and Transportation Department took on wider responsibilities for the countryside as a whole. In 1975 the Landscape Conservation Programme was launched with the aim of enhancing the appearance and condition of the countryside. Its first concern was the loss of trees and it provided advice as well as Landscape Conservation grants for farmland tree planting. However, by 1999 ‘developing ideas in conservation’ had resulted in extending the programme to include meadows, grasslands, heathlands, river valleys, historic parklands and other historic landscapes. The concept of encouraging ‘a sense of place’ and the ‘whole farm/holding’ approach in the different regions of Norfolk entered the terminology. Woodland in the form of copses, scrub, hedgerows, avenues, beech and pine belts, river valleys, ponds, historic parklands and commons were also now to be valued and their maintenance in good condition was eligible, if nothing else was available, for County Council grants. The importance of working in partnership with the various voluntary organisations and governmental departments was recognised.46 From 1997 Hedgerow Regulations had made it illegal to destroy a hedgerow if it was more than twenty metres in length or over thirty years old and the local authority was the enforcement authority.

49 How Hill windmill was restored with the help of a grant from the Norfolk Windmills Trust.

The other county Trusts

The challenges presented by the pressures on both the natural and cultural environment described above meant that there was plenty for both the NWT and the NAT to be concerned about. With the rapidly increasing membership of the NWT described above (35,000 by 2012), and with successful appeals for funds, further purchases of land were possible. While original acquisitions had concentrated very much on the north Norfolk coast and the Broads, with smaller areas in Breckland, other types of habitat were increasingly recognised as being under threat. Commons and woodland were added. In 1973 the cartoonist Osbert Lancaster gave the Trust East Winch Common. The two ancient woodlands of Wayland (1975) and Foxley (1989), became Trust property later. The Woodland Trust, founded 1972, has acquired Tyrrels Wood and other Norfolk sites. As well as owning sites, the NWT leases and manages other areas. One of its most unusual sites is the railway line at Narborough in west Norfolk, where the digging of cuttings has created an important chalkland habitat. The Trust now (2014) owns or manages thirty-eight different reserves. The emphasis has now moved from the acquisition of isolated areas to connecting sites to provide corridors between existing reserves. This policy has allowed the area of land owned around the Cley marshes to be greatly expanded as well as new acquisitions made linking several broads. The Trust now owns or manages 4,300 hectares. The Living Landscapes initiative involves working with partners across wider areas to give wildlife space to survive and adapt to change. As we have seen, the importance of interpretation and engaging the public has also been actively addressed. From its original centre at Ranworth, there are now visitor centres at Cley, Hickling, Holme and Weeting, with a board walk at Barton Broad and Thompson Common.

50 The ancient woodland at Foxley was purchased by the NWT in 1989. Bluebells flourish amongst the pollarded hazels.

51 The central area of Caistor Roman Town was given to the Norfolk Archaeological Trust in a bequest in 1984. Additional land was purchased in 1991/92 and 2011 to include much of the extra-mural settlement surrounding the town. The Roman street pattern can be clearly seen in the grass in dry weather.

Unlike the NWT, the NAT has been hampered by a shortage of members (there are still fewer than 100), but it has been very successful in recent years in attracting grants for purchase and interpretation. The introduction of agri-environment schemes has allowed sites which are purchased to be taken out of the plough, thus preventing further damage from both ploughing and illegal metal detecting. They are then put into an Environmental Stewardship Scheme which provides funds for their future management. Following its early acquisitions, described in a previous chapter, it was not until 1984 that any more properties were added. In that year, however, the central area of Caistor Roman town, surrounded by its late Roman defences, was given to the Trust. This scheduled site had already been removed from cultivation in 1973, but much of the Roman town lay outside the bequest and there was no vehicular access. Additional land was purchased in 1991 and 1992 with English Heritage and local authority funding. The holding now consisted of forty-nine hectares and was immediately put down to grass to prevent erosion of the archaeology by ploughing and sub-soiling. A car park for twenty-five cars was constructed and waymarked walks around the Roman defences and beside the neighbouring river were created, with a series of information panels beside the paths. A leaflet and site guide books are available in local shops. It was one of the first large areas to be put into a Stewardship Scheme, and was opened to the public by the chairman of the Countryside Commission in 1993. The project received five national awards over the next two years. In 2011 a further large field across the river containing an area of extra-mural settlement and Saxon occupation was purchased with the aid of funds from the National Memorial Fund (the first time a grant was given for the purchase of land). Other purchases included the Tasburgh iron Age enclosure (1994), the Saxon Shore fort at Burgh Castle (1995), the addition of the priory gatehouse and adjoining field at Binham Priory (2003 and 2005), St Benet’s Abbey (2002–04), South Creake iron Age fort (2003), Burnham Norton gatehouse and priory site (2011) and, finally, Fiddler’s Hill barrow (2012). All these sites are managed with wildlife as well as archaeology in mind.

52 Recent Heritage Lottery Funded work at St Benet’s Abbey by the Norfolk Archaeological Trust has involved new interpretation panels, one showing a reconstruction of the site.

52 Recent Heritage Lottery Funded work at St Benet’s Abbey by the Norfolk Archaeological Trust has involved new interpretation panels, overlaying an aerial photograph as it is today.

The future

Where does this leave the conservation movement today? From its early beginnings in the nineteenth century to the 1950s the movement can be seen as an exclusive one, supported by minority interest groups such as naturalists, archaeologists and architectural historians. The emphasis was very much on the preservation and protection of rare and exceptional sites. However, one result of improved standards of living and leisure opportunities, helped very much by mass communication and the spread of the motor car, has been the increasing awareness of and public interest in all aspects of the countryside. The conservation groups have responded to this by opening up their sites and introducing educational programmes. The importance of the typical as well as the exceptional has become understood and the emphasis has moved away from ‘preservation’ to ‘conservation’, and more recently, in planning terms, ‘regeneration’. Protection is not seen necessarily as negative and restrictive but, as in the case of FWAG and NMMP, as a partnership of interests between those who work the land and those who wish to protect its historical and ecological assets. The importance of diversity in ecological terms is better understood and is becoming more generally accepted in the farming community and encouraged through environmental grant schemes such as that pioneered in the Norfolk Broads. The closing down of much of the countryside to visitors during the foot and mouth outbreak of 2001 showed how important tourism was to the rural economy. The attraction of the countryside relies very much on its variety of flora and fauna as well as its historic and landscape interest. The early twenty-first century has seen the replacement of previous crop and livestock payments, which had linked production and financial support. Instead, under the Single Farm Payment Scheme farmers are paid by the acreage they farm and have to demonstrate that they are keeping land in ‘Good agricultural and environmental condition’. This discourages the ploughing up of permanent grassland and ensures that SSSis and Scheduled Ancient Monuments are protected.47

Much of this new thinking on conservation was reflected in Planning Policy Guidance 15 (PPG15), published in 2002 and entitled ‘Planning and the Historic Environment’. The importance of a partnership between local authorities, private individuals and businesses, as well as conservation bodies, is understood. The importance of education that emphasises the value of the natural and cultural landscapes is recognised as being an essential ingredient in the promotion of conservation. The significance of both the ‘wider historic landscape’ and the importance of conservation to tourism and regeneration is stressed. ‘Policies to strengthen the rural economy through environmentally sensitive diversification may be among the most important for its conservation.’48

In just over a century the legal protection of historic sites and monuments has moved from being voluntary to a far more complicated situation which recognises that such sites have a national significance which can override private ownership. Local planning authorities now have an important role in the protection of both ecologically and archaeologically sensitive sites, while at the same time acknowledging the importance of working with other interested parties. Through full consultation, together with positive and informed negotiation, conflict can be avoided and a compromise which suits all concerned can be achieved.

While the future for the natural and much of the cultural heritage in Norfolk looks positive as a result of partnerships between conservationists, on the one hand, and owners, farmers and developers, on the other, the outlook for much of the built environment is less rosy. Heritage protection is frequently regarded with suspicion. It is often seen as an ‘opposition movement … fighting against weather, time, decay, greed, ignorance, funding cuts, development pressures, Government policy …. Battling to stop bad things happening to the heritage … a position inherently weak and reactive and crucially (unlike those working for the natural heritage) we haven’t been able to get the message across to the larger public’.49 Listing is often seen as a negative move, to such an extent that it can stifle good modern architecture because developers do not want buildings that might end up listed, thus constraining what can be done to them at a later date.50 While the ‘heritage industry’ is being increasingly recognised as central to the economy of the countryside, government funding for historic buildings is declining.

However, to end on a more optimistic note, many of the conservation initiatives described in this book were pioneered in Norfolk, from the founding of the Wildlife and Archaeological Trusts in the 1920s to the forerunners of Environmentally Sensitive Areas in the Norfolk Broads in the 1970s and the Norfolk Monument Management Project in the 1990s. As a county traditionally associated with intensive farming, alongside some of the most important wetlands and coastal areas for wildlife in Britain, and with a history which saw it as the country’s most prosperous and populous region from the iron Age through to the Middle Ages, there is much to conserve. Initiatives which see the rich diversity of Norfolk’s landscape valued and cared for by those who live and work here, and enjoyed by the many who visit, should continue to be a key element in planning for the county’s future.

1 Lowe 1986, 55.

2 Scott 1942, passim.

3 H. Newby (1988) The countryside in question. London, Hutchison, 73.

4 Norfolk County Council 1994, 20–21.

5 Oxford Archaeological unit (1999) Management of archaeological sites in arable landscapes. Oxford, OAu, 5 and 37; Lawson 1981, 34-35.

6 Norfolk County Council, Broads Consortium (1971) Broadland study and plan. Norwich, NCC.

7 C. Chinery (1999) ‘Population’, in T. Heaton (ed.), Norfolk century. Norwich, Eastern Daily Press, 26–7.

8 D.N. Jeans (1990) ‘Planning and the myth of the English countryside’, Rural History 1, 261.

9 D. Matless, C. Watkins and P. Merchant (2010) ‘Nature Trails: the production of an instructive landscape in Britain’, Rural History 21:1, 97–131.

10 George 1992, 476–8.

11 Allison and Morley 1989, 10.

12 Sheail 1998, 210.

13 Sheail 1976, 228.

14 Sheail 1998, 165.

15 George 1992, 481.

16 Eastern Daily Press, 26 January 1981.

17 George 1992, 282.

18 Lowe 1986, 268.

19 The Times, 18 February 1984.

20 The Times, 11 February 1984.

21 Eastern Daily Press, 16 July 1984.

22 Eastern Daily Press, 3 July 1984.

23 Eastern Daily Press, 21 July and 15 August 1984.

24 Lowe 1986, 297; Eastern Daily Press, 18 August 1984.

25 Sheail 1998, 242.

26 Pers. comm. Peter Grimble and Greg Pritchard.

27 N.W. Moore (1987) The bird of time: the science and politics of nature conservation – a personal account. Cambridge, Cambridge university Press, 107.

28 Parliamentary Papers (1966–68) Report of the Committee of Enquiry into the arrangements for the protection of field monuments (The Walshe Report), Command Paper 3904, London, HMSO.

29 D.A. Edwards and P. Wade-Martins (1987) Norfolk from the Air. Norwich, Norfolk Museums Service, 9–10.

30 Bournemouth university and English Heritage (1995) The Monuments at Risk Survey of England. London, English Heritage, 11.

31 H. Clarke and A. Carter (1977) Excavations in Kings Lynn 1963–1970, Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 7. London, Society for Medieval Archaeology; D.M. Owen (1984) The making of Kings Lynn: a documentary survey. Oxford, Oxford university Press for the British Academy; v. Parker (1971) The making of Kings Lynn: secular buildings from the 11th to the 17th century. Chichester, Phillimore.

32 M. Atkin et al. (1982) Excavations in Norwich 1971–1978, Part 1. East Anglian Archaeology 15, Norwich, Norwich Survey in conjunction with the Scole Archaeological Committee, 1.

33 Wade-Martins 1999, 310–11.

34 B. Ayers and A. Lawson (1983) Digging under the doorstep. Norwich, Norfolk Museum Service; B. Ayres (1985) Excavations within the north-east bailey of Norwich Castle, 1979. East Anglian Archaeology 28, Norwich, Norfolk Museum Service.

35 B. Ayers, J. Bown and J. Reeve (1992) Digging Ditches. Norwich, Norfolk Museum Service.

S. Popescu (2009) Norwich Castle: excavations and historical survey, 1987–1998, parts 1 and 2. East Anglian Archaeology 9, Gressenhall, Norfolk Museums Service, 132.

36 T. Ashwin, S. Bates and K. Penn (2000) Norwich southern bypass, excavations 1989–1991, parts 1 and 2 East Anglian Archaeology 91, Gressenhall, Norfolk Museum Service.

37 J. Betjeman (2001) ‘A greatness in profusion’, in C. Roberts (ed.), Treasure for the Future. Norwich, Norfolk Churches Trust, 1.

38 P. Paget (1972) ‘How the Scheme for Redundant Churches is meant to work’, in

W. Harrod (ed.), Norfolk Country Churches and the Future. Holt, The Norfolk Society, 16.

39 Aims of the Norfolk Churches Trust as listed on the back of R. Greenwood and M. Norris (1976) The brasses of Norfolk churches. Norwich, Norfolk Churches Trust.

40 For a general survey of the Trust’s work see C. Roberts (ed.) (2001) Treasure for the future: a celebration of the Norfolk Churches Trust 1976–2001. Norwich, Norfolk Churches Trust.

41 H. Paterson and P. Wade-Martins (1999) ‘Monument conservation in Norfolk’, in

J. Grenville (ed.), Managing the historic rural landscape. London, Routledge, 137–48.

42 http://www.hoh.org.uk

43 J. Ayton (2013) ‘The first county development plan; part 2, after the plan 1951–71’, The Annual 22, 5–19.

44 Newby 1988, 40.

45 Ayton 2013, 19.

46 Norfolk County Council (1999) Landscape Conservation Targeting Statement. Norwich, NCC.

47 Rural Payments Agency, Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2006) Single Payment Scheme. London, DEFRA publications.

48 Department of the Environment (1990) Planning Policy Guidance: Archaeology and Planning. London, HMSO, 2:26.

49 Loyd Grossman, speech at Society of Antiquaries, Burlington House, London, 17 September 2013, ‘Heritage, Past, Present and Future’.

50 Chris Miele’s contribution to discussion at the above conference, 17 September 2013.