CHAPTER FOUR

Silk

With time and patience a mulberry leaf becomes a silk gown

Chinese proverb

The Legend

Lady Lei-Tzu, wife of the Yellow Emperor, sat with her attendants under the shady bough of a glorious mulberry tree. Sun filtered through the leaves, dappling the ladies with golden light: the perfect afternoon in which to tell stories and sip tea. Lady Lei-Tzu took a delicate cup of amber liquid, steam gently rising and tickling her nose, and with an elegant hand raised it to her mouth to drink. Plop. A small splash sent drops of hot tea falling onto the pearly skin, scalding it. Lady Lei-Tzu shrugged off the hurt and looked into her cup to see what had interrupted her refreshment. An oval ball floated amidst the jasmine leaves. With two slim fingers she tried to pluck it from the water but as she touched it the ball unwound into one long thread, soft and sticky and intriguing beyond anything she had encountered before.

It was the cocoon of a caterpillar that regularly feasted on the white mulberry leaves growing abundantly in the palace gardens. Lady Lei-Tzu looked up into the branches canopying over head and saw that under many of the leaves cocoons had sprouted like exotic fruit. She pulled one off, and beckoned to a maid to pour another cup. She dropped the swathed bundle into it and watched again as it began to unravel. The strand was finer than hair and felt so smooth and soft. What, luxury, the lady thought, to have a gown made from such a substance. From then on the empress was known as Lady of the Silkworm.

And so it is Lady Lei-Tzu, wife of the great mythical Yellow Emperor, Huang Ti, (traditionally his reign is put at 2677 – 2597 BC) who is popularly credited with the invention of silk as a textile and presides over silk rituals as its officiating goddess.

Silk! A soft, light, elusive material whose name has become synonymous with refined luxury whether it is referring to the taste of chocolate, an infant’s skin or the human voice. As a textile it stands apart from cotton, hemp, flax or wool, being neither a direct product of the soil or grown on an animal’s back. It is, instead, a seemingly magical thread produced by a small, insignificant grub. And the procedure for growing, harvesting and weaving the thread into glorious fabric, is, in the human scheme of things, an ancient one shrouded in mystery.

Lady Lei-Tzu drinking tea.

Discovery and early production of Chinese silk

The legend of Lady Lei-Tzu is unforgettably romantic but archaeological finds of dyed red silk ribbons have placed silk cultivation several hundred years further back in time than the 2700 – 2600 BC dates in which Lady Lei-Tzu was the consort of the Yellow Emperor. Impressions of woven silk fragments in baked clay, spinning and beating tools and carvings on cups and other implements depicting silkworms have been unearthed along the banks of the Yangzi River, providing further evidence that silk was being produced in China up to 7,000 years ago. One particular find, dating to 2850 – 2650 BC has been identified as silk from the Bombyx mori species. This dates the early cultivation of silk to just before or during the early reign of the emperor Fuxi, the first of the three mythical emperors. Fuxi, who preceded the Yellow Emperor and his lady, has also been accredited with discovering silk and overseeing the beginning of its cultivation. While this story has more archaeological evidence to support it, it does not complement the fact that women were the main silk textile workers.

The predominance of women in the industry of growing and weaving silk might explain why the story of Lady Lei-Tzu discovering silk became more widely accepted than that of the previous emperor’s. It may also explain why, in the early days of silk cultivation, Lady Lei-Tzu’s main rivals to the title of Lady of the Silkworm, were women. However, by the time of the Shang Dynasty and its many written records, Lady Lei-Tzu was well established as the major goddess of sericulture accompanied by a large cohort of minor silk deities, most of them female. The importance of women to the industry is reflected in the fact that rituals involving the silk goddess were the only ones officiated over by the empress instead of her spouse.

In the early days of sericulture worship it is believed that human sacrifices were sometimes made to ensure the continuing success of silk in all its aspects. This practice didn’t persist but the worship of Lady Lei-Tzu presiding over silk production continued right up until the Nineteenth Century by many female factory workers. The true origins of the discovery of making cloth from silkworm cocoons in China will always remain swathed in legend.

Silk, though a strong and resilient fibre, will not stand the stresses of time unless preserved under optimum conditions and therefore most early specimens disintegrated within years of its manufacture. Evidence, then, of the knowledge, use, and cultivation of the silkworm lies mainly with archaeological finds such as sculptures and carvings, tools related to reeling, spinning and weaving. For instance, one of the earliest pieces discovered was a carved ivory bowl with an engraved silkworm on either side.

The discovery of the cocoon as a source of silk was preceded by the use of the intestines of the silk worm itself. Again the proof lies in a depiction of a cocoon cut in half with a thread being pulled from inside the grub. The cocoon was apparently soaked in an acidic solution such as vinegar, sliced open and the gut of the caterpillar drawn out as a sinewy thread. This fibre is very strong and can exceed 100 metres in length. One could easily see how the progression from using the silk worm intestine to using the silk forming the cocoon could be made through the initial soaking process.

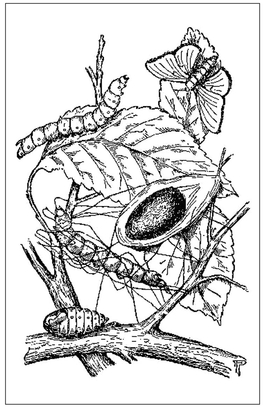

Bombyx Mori.

The biggest development in Chinese silk production and the reason that China tended to dominate the market for silk, was the domestication of a species of moth derived from China’s native wild moth, Bombyx mandarina moore. This species, through careful breeding and nurturing eventually became the renowned flightless and sightless Bombyx mori from which the Chinese were able to make the finest silk in the world. Not only was it the cultivation of this silkworm but the method for harvesting the silk, the reeling off of unbroken filaments from the cocoon, that were responsible for the success of Chinese silk, and it was these methods which they supposedly kept a national secret for so many years.

It has been suggested by some historians that perhaps it was not so much an issue of keeping a secret from the outside world in order to dominate the market that gave China its commercial edge but more the fact that the cultivation of mulberry trees and Bombyx mori in other parts of the world were just not successful.

Supporting this theory is the fact that at more than one point in China’s early history the demand for silk was so high in its own country that they couldn’t keep up the demand from the domestic market, let alone making enough silk to export it.

While mulberry leaves are not the only food that the Bombyx mori can eat (it is suggested that children in the western world, keeping them as pets or for school projects, can feed them ordinary lettuce leaves) it is definitely a highly suitable one. As the mulberry trees grow prolifically along the banks of parts of the Yangzi River, it was only natural that they would attract the silkworm moths as a food source for their young once hatched. The climate was right and a food source in abundance, the ideal set up for silkworm farming: more food, more grubs, more cocoons, more silk.

Silk follows the trade routes

Silk became known outside China well before the official recognised date for the start of trade along the Silk Road which has been put at the Second Century BC. The

Scythians had trade routes already operating in the Sixth Century BC that went from China to Eastern Europe. A number of quality silk items were unearthed from a frozen Scythian tomb in Siberia (dating to the Fourth to Fifth Century BC), including a delicate silk panel appliquéd onto a felt saddle blanket. These finds support the probability of the existence of earlier trade routes than the Silk Road. The silk panel from the Siberian burial chamber may, or may not have been of Chinese origin but it certainly wasn’t from Siberia.

The Chinese frequently used silk textiles as gifts for foreign dignitaries, offerings of peace to potential invaders along its borders and for other diplomatic purposes; it was used in dowries and as tribute. This meant that there was the potential for fine silk from China eventually being dug up from the tombs of ancient Egypt or other faraway places.

By the Fourth Century BC silk textiles, including those from China, were known to both the Greeks and the Romans, though these cultures were ignorant about how the textile was produced. For centuries the Romans believed that silk came from the underside of the mulberry leaf and was therefore a plant fibre. They did know that it was chiefly made in Serica by the Seres: the Latin words for the people and country being the same as for the textile. The silk that found its way to Rome, and caused such a sensation, would have got there via the Silk Road, probably brought by Arab or Parthian traders.

As it has been said, it is thought that not all the silk being traded was made in China. By the Second or Third Century BC silk manufacturing was already being undertaken in Central Asia and India though the fabric was made from the cocoons of wild silkmoths, not domesticated ones. Around 200 BC Korea learnt sericulture through Chinese emigrants who may also have introduced the Bombyx mori species of silkworm to that country along with the knowledge of how to raise them and reel off the silk. A couple of hundred years later there is documentation noting that the Japanese emperor was given a gift of silkworm eggs by his counterpart in China, and this was not the first or only gift of its kind between China and its neighbouring countries.

The secret is out

Whatever the facts were about the spread of sericulture beyond China, the fable behind how the carefully kept secret about silk was finally broken, according to the records of a Seventh Century monk, when a young Chinese princess was betrothed to a prince in Khotan, India. The thought of leaving her home, country and family did not bother the young lady nearly as much as the fact that outside China there was no knowledge of making silk. How could life be bearable without ready access to that luxurious of textiles!

The princess hid mulberry tree seeds and silkworms in her elaborate headdress and gave them to her husband as wedding present. He was more than delighted at having been given the means of a lucrative business.

Silk in Rome

However and wherever the silk was made, when it arrived in Rome it sparked a huge desire in the population for owning and wearing it. There were stories told that the demand for this particular luxury import was so strong that it threatened to cripple the Roman economy and in 14AD Emperor Tiberius issued a decree banning the wearing of silk because it was going to lead to decadence. Tiberius’s ban did not last because a hundred or so years later Roman envoys were sent directly to China in order to create a sea trade between the two civilisations. Trade between China and the west flourished and by the Tang Dynasty of the Seventh Century AD decorative influences from the west were flowing back to China to be incorporated in their own designs for the aesthetic taste of the Chinese as well as for the export market.

Chinese consumption of silk was heavy during the Tang Dynasty and it is recorded that Lady Yang, the Precious Consort, had seven hundred weavers allocated to making silk cloth for her royal robes.

Chinese silk weavers in Persia

Tang silk weavers were taken prisoner during the Battle of Talas, when China was defeated by the Persians, and were taken to Persia and Mesopotamia in order to teach the local textile workers the craft of silk spinning and weaving. Chinese secrets were slowly being dispersed into the vast world.

All the time, through trade and war, famine and feast, developments in weaving techniques were being made. Different cultures brought different influences and, as sericulture became established in other geographical locations, so novelty weaves such as cut velvet pile were applied to silk.

In the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries China had begun to weave silk rugs based on the technique of the Turkic tribes who had devised it for the use of wool. This coincided with the rise of chinoiserie in the west, the love of all things decorative with a distinctive oriental flavour. Exports from China included beautiful bolts of painted silk with Chinese designs adapted for European taste.

Mechanisation in China

Just as the Industrial Revolution in England had caused problems for the cottage manufacturer, so did the importing of machines to facilitate the reeling process in China. The negative effects of these machines did not last long and the industry settled and grew to such an extent that new areas of manufacture sprang up in China to satisfy world demand. While most factories embraced the new technology there were outposts of traditional practise that continued with the time honoured methods.

The revolution that saw the end of not only the Qing Dynasty but dynastic rule altogether did not halt the production of silk. It still formed a major part of the Chinese export economy and its biggest threat was the rise in popularity of synthetic textiles. The smaller silk producing centres were devastated and some of the social structures that had grown out of female involvement in the industry changed as a result when they had to seek lesser kinds of employment elsewhere. The larger silk producers incorporated synthetic fibres into their textiles to satisfy the new demands of fashion.

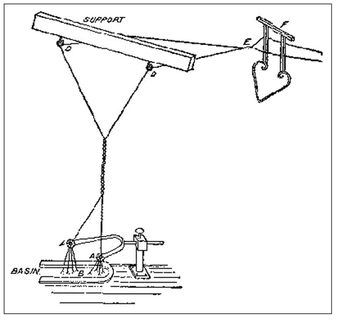

A hand reeling silk machine.

With the rise of the Peoples’ Republic in 1949, when luxurious goods were seen as evil, silk production managed to stand firm because it was still one of China’s major exports. It was not used by the general populace in any form of personal or domestic commodity but did find an artistic outlet in government propaganda. One good to come out of so much strife in a country under the iron thumb of Communism was the preserving of traditional methods of craftsmanship, including all the ways of working silk that were starting to diminish in the Nineteenth Century under mechanisation.

The Twenty-first Century has seen the rise of China as a major manufacturer of everything from plastic toys to motorcars and while silk is no longer a dominant export for China, China still provides a large bulk of the world’s silk.

Independent silk development outside of China

According to recent archaeological activity there is evidence that challenges the notion that silk production, perhaps even cultivation of silkworms, was not the sole discovery of the Chinese although it has been noted that the ancestor of the Bombyx mori silk moth (the moth used for producing China’s best silk thread) was a species unique to China.

Putting this point aside but not out of mind, finds such as the copper wire ornament with fragments of silk fibre still attached to it (dating to approximately 2450 BC) unearthed at an archaeological site of the ancient and prosperous civilisation of Harrapa, in what we now call Pakistan,throw interesting possibilities into the debate. And, on further investigation this thread is found to be made of a type of wild silk and not that of Bombyx mandarina moore (Bombyx mori’s great, great ancestor). The partially processed silk thread fragment (2500 – 2000 BC) seems to have been reeled in the manner of Chinese silk though the fibres themselves are from a wild species of moth. Silk made from wild moth cocoons is usually formed from spun, shorter threads because the cocoon has been broken when the moth has hatched from it.

Fragments of fabric made from a mixture of spun silk (as opposed to reeled) and cotton from 1500 to 1000 BC were found in India but this is almost all the surviving silk textile to be unearthed at such an early date. Silk fragments have also been found at an archaeological site in Germany dating to 700 BC, well outside the official date for the beginning of silk export from China to the West, though in the light of the evidence found at Harrapa it is possible the silk is from another silk producing area.

Production of silk in the West

Whether it happened through gifts of silkworm eggs and mulberry seeds given to foreign diplomats and emperors or through ancient industrial espionage the secret of sericulture spread to Korea and Japan, from Persia to Byzantium. Chinese silk craftsmen captured in battle found they had to make silk and teach reeling and weaving skills to their captors. In the Eighth Century AD silk was being produced in exportable amounts in central Asia by Chinese prisoners of war taken by Arabs. The silk that was produced by these slaves was of the same high quality as that produced in China.

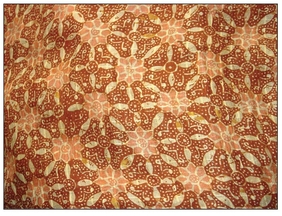

A silk scarf made for the Western market.

Silk was traded and sold all over Europe and sericulture followed along with it into Spain, Italy and other parts of Western Europe where the climate was conducive to the growing of mulberry trees and the rearing of silk worms. England, unfortunately, proved too wet and cold for silkworms to survive, let alone thrive, and silk, or at least the raw materials, remained an imported product.

Byzantine silk

Byzantium in the early centuries AD was the jewel of the world and almost everything bright and beautiful either passed through it on the way to somewhere else or it was made there and then sent on its way. The Byzantines learnt all aspects of Chinese sericulture, from the nurturing of precious mulberry trees to the reeling off of the filaments from unbroken cocoons and then weaving it into cloth as light as air using specialised weaving and spinning skills they’d learnt from the Persians and Syrians. The Byzantine craftsmen could also perform the elusive and complicated task of spinning silk ‘organzine’, a four-strand thread from which the strongest, most lustrous and costly silks could be made.

For centuries Byzantium had a strong hold on the silk trade, not only producing and manufacturing it but also distributing it. By the Tenth Century AD Byzantium was at its peak in the silk world but from the Eleventh Century onwards there was a decline in its power through a succession of wars, not only from outside attack but also from civil discontent. The Byzantine capital, Constantinople finally fell to foreign invaders in the Fifteenth/Sixteenth Century.

Silk production in Europe

Displaced silk workers, fleeing strife in Byzantium, found their way to Europe. Moorish traders had already introduced the silk industry to Spain and established workshops there where Byzantine craftspeople found a welcome home. Italy was another major centre where silk workers settled and resumed their craft. In fact Italy became one of the best known European producers of silk yarn and fabric. The Italians, following the fabled secrecy of the Chinese, subsequently shrouded their own knowledge and inventions for reeling and spinning silk organzine with similar zeal.

Lucca was the site of one of the earliest water driven silk throwing (the process of twisting the reeled fibres together to form a strand of yarn) mills enabling the production of the prized organzine with ease and speed not possible with the laborious hand throwing method. The reeled silk has to be twisted (thrown), doubled and twisted back on itself to form the four-ply thread and a machine that could be powered by water to turn the spindles for this was an invaluable invention. Over the next hundred years the device was installed at the major Italian silk centres in Florence, Bologna and Venice.

By the end of the Fifteenth Century France wanted to be part of the silk making world. Under Louis the XI, Italian silk specialists were taken to the centres of Lyons and Tours where they were required to teach local people the art of weaving silk. The Italians had not brought with them the secrets of throwing silk or the secrets of how to make organzine thread. At this time in Italy it was forbidden to tell these secrets in forfeit of your life: silk spinning was a deadly game.

It was only a matter of time before French weavers were able to produce fabric as beautiful as the Italians, using, of course, imported silk thread. The French specialty was their ability to produce exquisite new designs in fabric every year. By 1667 it was impossible for the Italians to compete with the French in their imaginative and prolific output of designs. The French had not been idle in the matter of inventions either and had adapted the draw loom so that all sorts of woven textures could be achieved. Amongst others there was chenille, crêpe de Chine and chiffon.

Not to be outdone by its ancient rival, France, England too had to be part of the luxury silk industry. James I was instrumental in getting silk weaving established in Britain. He gave incentives to nobles to set up groves of mulberry trees in which to nourish silkworms to get sericulture started in England. Black mulberry trees were used in place of the traditional white mulberries of China, possibly because they were more tolerant of the colder, wetter weather that England was notorious for. Even though several serious attempts were made, including the planting of 2,000 mulberry trees in Chelsea Park, London, sericulture never thrived.

Silk in the colonies

It was also James I who introduced sericulture to the American colonies in 1619. The industry took hold within certain New England communities like the Shakers but remained a cottage industry. In the Eighteenth Century New Jersey became a major silk producer although the US relied on imported Japanese silk for the bulk of its silk fabric.

Silk weaving in Britain

Even though Britain couldn’t produce its own silk there was no shortage of skilled labour in the weaving of it and consequently it was able to set up successful weaving factories. The persecuted Huguenots had fled to England, amongst other places, and a fair number of them had been in the weaving trade. Their presence was welcomed and indeed actively sought as early as the reign of Queen Elizabeth the First.

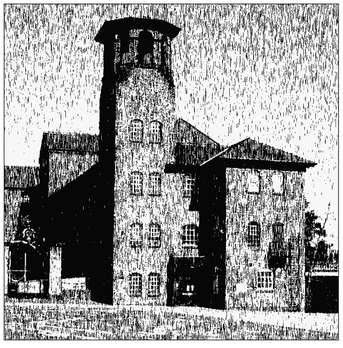

A silk processing mill in Britain.

A century later a wave of some 5,000 refugees settled in Britain and with them they brought the skill of making lustring – a fine, light, glossy silk. This involved stretching and heating the silk thread.

Spitalfields, just outside of London, was chosen as the site of the Royal Lustring Company by Eteienne Seignoret, a silk merchant originally from Lyon. The silk woven in this mill was called ‘flowered silk’ after one of its most popular designs, though flowers were by no means there only design. English silk hit the export market with huge success.

There was still the matter of organzine silk thread to be taken care of. No matter how many skilled craftspeople came from the continent, none of them had brought the secret of the machinery behind its viable production. To make it all by hand was incredibly tedious even with the use of a spinning wheel and an undernourished waif to run the length of the mill in order to wind the thread around a ‘gate’ at the other end to enable the doubling process.

Espionage and murder

Two brothers, Thomas and John Lombes, both in the textile trade, decided to investigate the Italian secret.

John went to Italy and, pretending to be a worker, bribed his way into a factory where he surreptitiously sketched the water driven mill. He was caught in the act but escaped with his drawings back to England where his brother built a spinning machine to the specifications of the Italian model. Intriguingly, John was later poisoned by an Italian woman, perhaps a hired assassin, for his theft of industrial secrets.

Thomas grew rich on the earnings from his new machine and was further enriched when the government of England paid him £18,000 for the patent on it.

Silk in Ireland

Ireland also saw its share of Huguenot refugees and the silk industry tried to take off in that country too. For various reasons the silk trade did not prove as easy or as successful to run as it was in England. Workers were angry at the introduction of powered machines because it meant workers were laid off and riots ensued. Imported silk did nothing to support the Irish industry even though the Hibernian Silk Warehouse, established in 1765 did what it could to help. Again there were attempts at growing the raw material with the planting of 80 acres of mulberry trees. This attempt failed, but a monastery of Cistercians was able to cultivate silkworms and process the cocoons in order to make silk cloth, though this was much later in the early Twentieth Century. It did prove though that it was physically possible to farm silkworms in that kind of climate.

Silk weaving continued to grow as an industry in Britain. Advances in weaving technology in the Nineteenth Century meant that silk could be produced at a much greater rate and therefore could be sold at a much lower price, bringing it within the range of more of the population. The stress of supplying cheaper silk to the general public meant that there was always the threat of a fall in quality of the finished goods.

Dyeing and printing methods for catering to large quantities of consumers lead to innovations in both these areas and the use of the new aniline dyes broadened the colour spectrum considerably. As the dyes evolved spectacular hues were achieved making the already sumptuous textile even more alluring.

The Queen wears mauve silk and then black

Queen Victoria was instrumental in making mauve silk all the fashion and after Albert’s death, she was the instigator of the fashion for black mourning wear, popularly black crepe silk.

Silk remained in demand, just as in China, well into the Twentieth Century, and again, owed its reduced popularity not to war but to the rise of man-made fibres such as nylon.

Twentieth Century attempts at English sericulture were undertaken by Zoe Lady Hart Dyke at Lullington Castle in Kent. England is still one of Western Europe’s main producers of silk fabric.

Thai silk

Thailand did have an ancient tradition of sericulture that has been revived in the Twenty-first Century. It produces silk from two main types of wild worm, one cultivated and the other wild: Bombycidae and Saturniidae respectively. The silk is still often hand reeled and woven in home industries, despite the modern day technologies available. The silk is soaked in hot water and bleached in order for it to take dye as wild silk is notoriously resistant to dye.

Silk weaving in Thailand.

Cultivated Silk Process

Bombyx mori spins a long, fine, even filament for its cocoon and when it is harvested it produces a much longer thread than that of its wild cousins. The resulting silk is considered finer and more desirable. The process for making this kind of silk involves killing the unhatched pupa in its cocoon. It is killed before it breaks through the cocoon in order to preserve the length of the filaments. Throwing the cocoon with its pupa into hot water serves the double purpose of killing the insect and loosening the sericen, the binding glue, of the cocoon and freeing the threads for reeling off as unbroken thread.

Life cycle of Bombyx mori

The life cycle of the Bombyx mori moth begins with the female laying approximately 500 miniscule eggs over a period of four to six days on specially prepared trays. The moth having accomplished its purpose of reproduction and, having no mouth to feed with, will die relatively soon after.

The tiny caterpillars emerge from their eggs about ten days later and are as fine as a human hair and only 3mm long. They will grow to be 10,000 times the weight they were at hatching, outgrow and shed their skins four times and become fully grown at 10cm in their first seven weeks of life. As they grow they are placed on trays of fresh mulberry leaves.

Every two hours a frame with netting covered in leaves is placed over the old one. The caterpillars wriggle through to attack their new food source. When the caterpillars are ready to pupate they are supplied with a different kind of frame from which they can attach and spin their cocoons.

The life cycle of the bombyx mori silk moth.

Spinning the cocoon

Silk moth eggs.

From two glands within the head of the grub, but forming into one tube-like outlet, the worm spends three days moving its head back and forth in a figure of eight, an activity which winds the silk around its own body, eventually sealing itself within the cocoon.

Over a period ten days the pupa will metamorphose into a moth.

What happens next

If, as is the case with fine Chinese silk, the object is to get as long and fine a thread as possible it is necessary to kill the pupa before it hatches, this is to keep the filament intact. This is performed through application of heat in the form of boiling, steaming, baking or immersion in a salt bath. The cocoon is then put in a vat of boiling water to release the filament from the gum, sericen, which holds it all together.

The loosened thread is picked up and wound straight onto a reel (the process is called reeling) where a single thread can be as long as 2,000 metres. It is usual to reel the silk from several cocoons at once which also twists them into a single thread. The spun thread is then wound into skeins and collected into books. The silk is then thrown and processed into the type of yarn desired for weaving (for instance, organzine).

Cocoons that have broken can have their short fibres spun into thread just as a sheep’s fleece is.

In ancient times all this was done by hand. Reeling was performed with a wooden instrument, often formed into a ‘H’ shape. This was replaced by the spindle wheel, originally used for flax and hemp fibres. The silk was reeled directly onto wooden reels which were then placed on spindles. The thread was cleaned of excess gum, knots etc and thrown into hanks.

Waste silk

As in nearly every kind of processing, silkworm cocoons produce a waste product. The outside of the cocoon, and the threads that attach the cocoon to its frame are not able to be reeled but it doesn’t mean they can’t be used. These extra bits are gathered together and spun as cotton or wool is. The textile has quite a different texture to that of purely reeled silk but it has its own beauty.

Wild silk

There are many species of silk moth throughout the world, possibly more than 500, although not all of them spin a cocoon from which silk can be made. As has been mentioned earlier, it was probable that locations other than China were producing quality silk for export in ancient times, perhaps even contemporaneously; the Harrapa civilisation in the Indus Valley for instance.

What differentiates these silks from Chinese silk is the fact that they relied upon wild silk moth cocoons from which to make the yarn, whereas China’s reputation for fine silk textiles was due to its domestication of the silk moth Bombyx mori. China silk was unparalleled in its strength, fineness and smoothness of thread and lustre.

In modern, or at least, relatively modern times, wild silk has been used for making textiles in Africa. In the highlands of Madagascar the silk moth species known as Borocera Madagascariensis provides the filaments for weaving a naturally dull brown silk that is of a coarse texture and is used primarily for the making of shrouds. It does not take dye well.

In Northern Nigeria there are a couple of varieties of the species Anaphe: Anaphe moloneyi and Anaphe infracta. These caterpillars eat the leaves of tamarind trees. The two varieties differ in that infracta grubs group together when they spin clusters of cocoons with a common covering. They must be separated before the individual cocoons are processed for their silk. The ensuing silk thread is dull brown and feels as coarse as the Borocera Madagascariensis silk. Anaphe moloneyi do not form clusters like their cousins but each caterpillar spins its individual cocoon like the Bombyx mori. The moloneyi cocoons are white but the silk is a light beige colour when spun into yarn.

Earlier production of silk in Africa can be dated back to the Tenth Century AD where contemporary written evidence points to an already well established trade in silk export from Tunisia.

A wild silk moth type.

It was, however, China that held a monopoly on the secrets of sericulture and trade in the finest quality silk threads and woven textiles. Both the domestication of the silk moth and the process for recovering the filaments are the key to the Chinese success in making silk.

Wild silk is the textile made from the cocoons of uncultivated moths. The broken cocoons of hatched moths are gathered from the trees the larvae feed on and then processed in a different manner to that of cultivated silk.

Tussah silk from India is usually made from wild silkworm pupae although it has been semi cultivated in China, it can be de-gummed and reeled like the filaments from Bombyx mori.

Wild silk moth types

- Antheraea pernyi: This moth is native to China and can be de-gummed as in Bombyx mori. The natural colour of the silk is dependent on the climate and the soil

- Antheraea assamensi: A wild moth found in Assam, India. It has a natural golden sheen for which it is famous and was reserved only for the use of the Royal family of Assam. It is never dyed or bleached and its natural colour improves with careful ageing

- Antheraea yamamai: This is a wild moth though it has been cultivated in Japan for a 1,000 years. It is naturally white but will not take dye well. It is not produced in any great quantities these days

- Antheraea polyphemus: is native to North America

- Ansiota senatoria: Native to North America called the ‘orange-tipped oakworm moth’

- Gonometa postica: Native to the Kalahari

- Gonometa rufobrunnae: Native to southern Africa and feeds on the Mopane tree

- Alaskenaras Silkiterious: silk worm from Alaska

- Antheraea assamensis: are terminus feeding and spin cocoon with a convenient exit hole which means the thread can be de gummed and reeled off after the moth has flown

Woven silk scarves by Annamaria Magnus of Woodbridge Handweaving Studio.

- Early attempts at making aeroplanes often used a lightweight frame covered with stretched silk. Despite its delicate appearance, cultivated, reeled silk is surprisingly strong

- Silk is a poor conductor of electricity and tends to become static with it

- It takes approximately 5,500 silkworms to produce 1 kg of silk

- The eggs are miniscule and a gram comprisea a hundred or so of them. From 28 grams worth of eggs come approximately 30,000 silkworm grubs

- One ounce (28.34 grams) of Bombyx mori eggs brings forth 20,000 silkworms, which in turn can eat about a tonne of mulberry leaves during their larvae stage

- Silkworms have prodigious appetites, so it is necessary to have a large supply of fresh food for them. That many tiny mouths can gnaw their way through a tonne of mulberry leaves. Yet the same number of cocoons will only produce five and a half kilos of silk

- In the early days of silk cultivation and production, the cocoons were gathered and killed just after the grub had finished spinning its cocoon

- The dead pupae can be used as food they are high in protein

- Silk is one of the strongest of the world’s natural fibres, however, it loses about 20 per cent of that strength when it is wet

- Silk has relatively poor elasticity, once stretched it tends to stay that way

- ‘Peace Silk’ is a term invented to be applied to silk produced by methods which don’t involve killing the un-hatched pupa. The moth is allowed to emerge through the cocoon wall, breaking the filaments in the process. The silk is processed by spinning, not reeling and typically has a rougher, less even finish. Peace silk is not necessarily derived from wild silk moths but rather cultivated moths left to their natural life cycle

- The exportation of information about sericulture from China to the outside world was, for a long time, punishable by death

- The fineness of the filament from the pupae’s cocoon is shaped by the grub’s orifice from which the thread emerges. Bombyx mori produces the best shaped fibre

- Leonardo da Vinci tinkered with the idea of a water powered silk machine

- Over the thousands of years of its domestication Bombyx mori evolved to become blind and flightless; adapting, it would seem, to its sole purpose of breeding more silkworms and spinning silk cocoons for the benefit of making silk fabric

- Silk has been used to make parachutes, bicycle tyres, artillery gunpowder bags and even bulletproof vests

Glossary specifically for silk, including imitation silk

Barathea: brightly coloured, striped silk originating in India as the distinctive dress of the Bajadere dancing girls whose lives are dedicated to dancing.

Bengaline: originally a pure silk product from Bengal in India, now often made of wool, cotton and synthetic fibres. It has a ribbed texture.

Brocade: originally a luxury and decorative silk weave but no made in a variety of fibres. The pattern is woven against a twill ground or vice versa.

Brocatelle: originally a silk fabric but now made in other fibres. It is supposed to have been inspired by the craft works of Italian tooled leather. It features a twill pattern on satin ground or vice versa. The main effect is of embossing.

Camocas: a luxurious fabric that was very popular during the Renaissance. It featured gold or silver thread and was composed of silk and linen.

Cendal: silk fabric that looks like taffeta that was in use in medieval times. Charmeuse: is divided into two types, satin charmeuse and crepe charmeuse depending on the weave. It has a particular lustre and lends itself well to draping.

Chiffon: comes from the French word meaning rag. Originally made of silk but now made of a variety of fibres. Its characteristics are of a sheer, lightweight fabric composed of tightly twisted yarn.

China Silk: the original Chinese made Bombyx mori, reeled silk fabric.

Crepe de chine: a sheer, textured fabric with a raw silk warp and a twisted silk filling.

Crepon: was originally a wool fabric but now often made of silk or rayon. Has a wavy texture.

Cultivated Silk: is the silk made from domesticated silk worms killed before they can emerge from their cocoons in order to keep the filaments whole. This kind of silk is of the highest and finest quality. It is very strong because the threads are not composed of short, spun fibres.

De-gummed silk: silk fibre which has undergone a process, usually of boiling in water, to remove the sticky sericin (glue-like substance) that coats the fibres.

Duppoini Silk: has a distinctive texture which feels coarse to the touch. It is a strong fabric with a lustrous sheen.

Faconne: from the French word for fancy weave. The patterns on the fabric are made of a denser weave than the background.

Faille: a fine material that resembles grograin in its weave and has a lustrous finish.

Foulard: originally an Indian silk, a fine, light fabric with a small printed pattern on a dark or light background.

Frise: this is a looped fabric with a background of cotton or other sturdy fibre. The loops may be cut to form a pattern or uncut or a mixture of both.

Glove silk: made on a warp knitting frame with a fine knit. Used for gloves and underwear.

Habutai Silk: also known as china silk. It is not as fine as cultivated or mulberry silk but is a much cheaper option.

Honan: a top quality wild silk, similar to Pongee silk, made from silkworms found in the Honan region of China. It is the only wild silk that will dye evenly.

Illusion: a very fine silk gauze that was a product of France, it has an open mesh weave.

Lamé: a fabric with silk thread running through it, not limited to silk but often used with it for a luxury fabric.

Marquisette: an open weave, mesh-like weave with a swivel dot or clip spot, which gives it its name.

Matelasse: a fabric with a quilted appearance produced on a jacquard or double loom in a double cloth weave. The quilted look is made by the use of crepe yarn in double weave which shrinks and gives it its distinctive texture.

Messaline: a soft and lustrous silk fabric named after the third wife of the Roman Emperor, Claudius.

Moire: a stiffish fabric with a watermark design imprinted onto the fabric by inserting it between engraved rollers. The effect is not permanent.

Momme Weight: is the standard measurement for a piece of silk measuring 100 yards long and 45 inches wide.

Mousseline de soie: is basically a silk muslin, light, open and sheer.

Mulberry Silk: is not only a cultivated silk made from unhatched cocoons but is a silk made from the Bombyx mori silk moth larvae that have been fed exclusively on mulberry leaves. Mulberry silk is considered to be the best in the world.

Net: this fabric is made by knotting on a lace machine and is used as the basis for lace.

Noil: is sometimes called raw silk but this is a misnomer. It is actually a fabric made from the waste silk of the cultivated silk moth. It is of an inferior quality to other types of silk being not as strong and not able to accept dyeing as well.

Organza: is a fine, light and crisp finish with a silvery sheen. Has a springy feel to it.

Ottoman: has very definite flat ribs and is sometimes called Ottoman cord or Ottoman rib. It is a very stiff and heavy fabric.

Panne: from the French word for plush. It looks like lustrous velvet but with a longer pile.

Peau de cygnet: from the French for ‘swan skin’. It is a textured lustrous fabric made of crepe yarns.

Peau de peche: from the French for ‘skin of peach’. The fabric is given a soft nap finish after weaving, resembling the down on a peach.

Peau de soi: from the French for ‘skin of silk’. A satin type finish with a dull lustre.

Pompadour taffeta: a silk taffeta with floral designs in a velvet pile on the taffeta ground.

Pongee: a wild silk fabric from China that was made on hand looms. It is light weight and has a natural tan or ecru colour.

Satin: conjures up a smooth, glossy fabric that is synonymous with luxury. However, satin refers to the type of weave rather than the material from which it is made. It is often made from man-made fibres such as acetate, polyester and rayon, though it has of course been made from silk as well.

Silk Velvet: velvet is again the type of weave used not the raw fibre from which it is made. It is possible to get cotton velvets and these days, man-made fibre velvets. True silk velvet costs a fortune.

Shantung: a silk made from Tussah wild silk or silk waste. Similar to Pongee but is usually heavier and coarser.

Spun or Cut Silk: this is made by spinning the shorter fibres of the silk cocoon, a bit like the waste silk used in Noil silk. The filaments are sometimes taken from the inside area of the cocoon which is not as strong as the outer, longer filaments. Spun or cut silk is also made from the short fibres of the wild silk moth..

Taffeta: from the Persian word for ‘fine silk fabric’. It is smooth with a sheen and a crisp finish.

Thrown or Reeled Silk: the cultivated silk moth is killed before the filaments are removed, which they are by a process known as reeling, or throwing. This means that the end of the filament is secured and then carefully wound onto a bobbin in one continuous length.

Tricot: is a knitted fabric with a thin texture.

Tulle: a knotted mesh made on a lace machine. It gets its name from its place of origin, Tulle, in France. It is a stiff open mesh fabric, traditionally used in the underskirts of ballet tutus.

Tussah Silk: is made from the wild silk moths of India and China.

Velvet: has a pile weave with extra warp yarn. The word velvet comes from the Latin vellus which means fleece or tufted hair. Silk velvet is a very expensive fabric.

Wild Silk: silk made from the cocoons of moths that have already hatched and therefore broken the filaments of their cocoons. The shorter threads are spun after de-gumming and the silk has a quite different appearance and feel to that of cultivated silk but has its own beauty.