CHAPTER NINE

Dyeing

What should be the next natural step after having perfected the arts of spinning and weaving but colouring it? It must have been an early discovery because many of the textile artefacts unearthed by archaeologists are definitely coloured.

Perhaps we shouldn’t really put dyeing in to a section on surface decoration as the nature of dye is to become integral with the fibre. However, it is a process that is added to the fibre, either before spinning, before weaving or afterwards.

The earliest dyes were found in natural objects that were available at the place of manufacture. Many of these dyes are still used today, particularly by hand crafters and environmentally concerned manufacturers.

There are three types of natural dye: substantive, vat and adjective. The first of these, the substantive dyes are those that can be used without the need of a fixative. The second lot of dyes are known as vat because they need to be fermented before they can be used. They will often not show their colour until taken out of the dye bath and exposed to the air. The third type of dye is called adjective and, in order to hold its colour in the fabric, it needs a mordant, a metallic compound of aluminium and iron or copper. A mordant is a bonding agent that acts on both the dye stuff and the stuff to be dyed.

One of the largest sources of natural dye is plants.

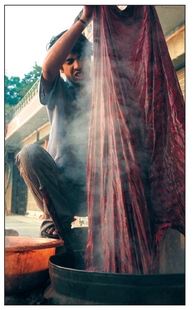

Hand dyeing in India, courtesy of David Dunning, Anokhi Hand Printing Museum, Jaipur, India.

Yellow

Yellow can be obtained from: dyer’s broom, fustic from the mulberry tree, onion skin, osage orange (also from the mulberry tree), pomegranate, oak, rhubarb, weld, chamomile, goldenrod, blackberry, ragwort, tansy, turmeric powder and birch. Many of these dyes will need a mordant although, rhubarb, onion skin and pomegranate will hold quite well without.

Red

Red has been extracted from the madder root for thousands of years. It can tint a fabric a delicate pink or dye it a deep, rich red. Dye from this source may be used with or without a mordant although for the richer and brighter reds it will help the colour retain its brilliance.

It is not just the roots that can be used as a dye, the plant tops also produce a red colour though tending towards the tan and rust rather than true red. It too can be used effectively with and without mordants.

Madder root will also make deep and lovely purples if used with certain recipes.

Orange

Orange is a colour that can be achieved by using a red dye and certain mordants or modifiers, or yellow dyes and additives. One of the commonest ways of producing an orange is to firstly dye the yarn or fabric in one of the two colours, red or yellow, and then immerse the fabric in the other colour. In some cases it is possible to combine the two dye baths, rather like mixing paint.

Plants that produce an orange colour from red dyes are: brazil wood and madder root. Onion skin, traditionally a yellow dye has definite orange overtones and if used in a high proportion of skin to water the colour will intensify.

Blue

Indigo, like madder, is an ancient dye. It is also the only natural dye to obtain a real blue. It comes from a limited number of plants that happen to be found worldwide. Woad, the war paint of the early Britons and other tribes, is an indigo producing plant.

Being a vat dye, indigo plants need to be soaked for some time in a liquid mixture. Many recipes for indigo call for stale urine as a component of the dye bath which is considered offensive to our modern day sensibilities.

Indigo has had many rituals and superstitious beliefs attached to its properties and its processing. The island of Suva in South-east Asia has a mythology regarding the two different groups of people inhabiting it based on their matrilineal ancestry. It is believed that two sisters were about to be initiated by their mother into the secrets of true indigo making. One of the girls crept out the night before their induction into the dyeing process and stole the vat of indigo waiting for the next step. Through her ignorance she poured off the top layer of liquid thinking it would be sufficient for her to turn into a deep blue. Unfortunately for her she had taken the superficial layer which contained little colouring.

To make true blue indigo it is the bottom layer, that which has been fermenting that is the precious potion with which to make it. For the two sisters, one founded a family who could not produce the colour but only a thin ghost of it while the other, who waited for her mother’s instruction, became the mother to the real dyers of the island.

Green and Purple

Just as orange can be made by mixing or over dyeing red with yellow, so purple can be made by dyeing red and blue. Purples can also be got from: bilberries, black currants, blackberries (look at how it stains the fingers when picking them), elder fruits, and sloe.

Green too, is another colour that is hard to find in one plant source and is therefore usually obtained by mixing a yellow and blue dye. It can be found in fairly dull hues in the following plant sources: bracken tops, goldenrod, ivy berries, privet, lily of the valley and nettle.

Plants are not the only natural source of dye pigment. Tyrian purple, or imperial purple is made from a shellfish. It was long considered a luxury dye and purple became synonymous with royalty.

Other dyes, like the lovely cochineal, are got from insects of the Dactylopius species; only the females are used. These insects are native to South and Central America and, while used by the indigenous people of the area since at least 3,000 years, it did not become known or available to people on the other side of the world until Europeans conquered South America.

Two other insect based dyes are a bright red or scarlet colour produced by the egg sac of the female Kermes insect that feeds on oak trees and the other is the Lac or Sticklac from Asia that produces a resin which is the source of the pigment.

Plants, insects and shellfish weren’t the only sources of natural dye. Earth pigments like ochre are still used by people today. Earth pigment can range from white to yellow, brown and red. It was used straight from the ground, and apparently there is a tradition of burying the piece of fabric or thread to be coloured in the ochre in the ground and left there for a period of time until it has taken the hue of the surrounding earth. Mostly though, ochre was put into a pot of water which was then evaporated to leave a concentrated pigment that could be further dried for storage and later use or ground directly and further diluted or applied to the fabric.

Natural Mordants

Mordants were found in nature alongside the dye sources they needed to modify. Some of these come from plants too: tannin from oak galls, blackberry leaves and twigs and alder bark; oxalic acid from the poisonous rhubarb leaf and, less socially acceptable, urine.

An iron based mordant can be made if you soak rusty iron in a mixture of water and vinegar. The same can be done with copper.

Chemical dyes

Chemical dyes weren’t really invented until the mid Nineteenth Century. In 1856 a chemistry student, William Henry Perkin, was conducting an experiment to try to recreate quinine. He was unsuccessful in his aim but he was successful in making a purple matter that he discovered could dye silk purple.

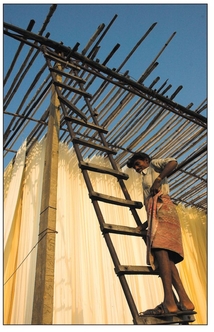

Drying the cloth, courtesy of David Dunning, Anokhi Hand Printing Museum, Jaipur, India.

Perkin’s discovery, mauveine, led the way to a whole range of synthetic dyes including a version of madder, in 1869, and indigo, 1878. In 1878 a group of synthetic dyes were created called organic azo-dyes. These formed the basis for many of the dyes used today.

With the invention of spinning and weaving machines driven by steam power it was inevitable that someone would come up with a way of producing strong, bright and colourfast dyes.

Ways of dyeing

As with everything else, mankind is never content with the simplest form of anything and dyeing yarn and fabric is no exception. It was not long after the discovery of making dye and immersing fibres in it to give them colour that humans began experimenting with ways of making the colour even more interesting.

One of the simplest ways to achieve interest in decoration is to dye the spun yarn in several different colours along its length. This is not over dyeing in order to achieve secondary colours but only dipping portions of a skein of yarn into each different colour dye bath. When it is then woven into cloth it will be multi-hued.

This simple method has itself been taken to a high art with a form called ikat (meaning to bind). Bunches of yarn are tied at intervals along their length with a dye resistant cord (traditionally silk) and then dyed. Sometimes the process is repeated up to three times, covering the already dyed area with cord before re-immersing. The yarns then form the warp or the weft of the fabric to be woven. It is rare to have both warp and weft dyed in this way. The resulting geometric patterns are amazing and show how much planning is needed to achieve this effect.

Tie-dyeing

A less complex form of resist dyeing (the term used for a process where another substance prevents the cloth from dyeing in that spot) is tie-dyeing, the popular handcraft of the Seventies.

The cloth is tied tightly with pieces of string or bunched and held with rubber bands. Pegs have also been used to make a pattern by preventing dye from reaching the cloth.

The patterns this method can produce are simple but fun and certainly distinctive. It is a good activity to do with children using white tee shirts and a cold water dye.

To go a step further with this type of dyeing why not stitch and pull the surface of the cloth? This is called trikit. The stitching is only to make folds and creases in the fabric, the firmer the better and it is the pressure of these that provide the resistance to the dye, not the thread that makes the stitches.

Batik

Then we get to batik (meaning wax writing). The method of using wax as a resistance to dye is ancient and its origins are obscure. Linen used to wrap mummies in ancient Egypt (Fourth Century BC) was soaked in wax and a design scratched into the surface and then dyed. It has been used in several Asian countries but it is the Indonesian island of Java that has become famous for its batik fabric.

The dye for batik must be a cold water dye as any heat would melt the wax. The best wax mix is 30 per cent beeswax and 70 per cent paraffin. One of the desired effects of batik is to get a subtle crackling effect where the wax has cracked and let tiny amounts of dye into the fabric. This needs to be controlled and that is where it is necessary to have the right proportions of the two waxes. Beeswax is the most adherent of the two and does not tend to crack. Paraffin on the other hand is far too brittle to be used by itself.

Batik cloth from Indonesia.

A design is drawn onto the cloth and hot wax applied to the area that is not to be dyed the colour of the first bath (the baths need to go from lightest to darkest). The wax can be applied by brush or dripped on but special tools can be bought, little copper reservoirs with a fine pouring spout, that hold an amount of hot wax like a pen holds ink. These are called tjantings.

The first dye bath is made and the piece dried. More wax will be added to preserve the colour just dyed. Subsequent dyeings are made. Wax can be removed between dye baths, if they are uncovered to receive a pure colour. When the piece is finished and dried all the wax can be removed by immersing in a solvent or ironing between sheets of paper.

To make the dyeing process quicker and to make repetitive patterns carved wood blocks are used. The hot wax is coated onto the woodblock, adhering to the raised surface of the carving. It is then planted face down onto the fabric and held in place until the hot wax infiltrates the fabric. The process is repeated.

Batik cloth from Indonesia.