CHAPTER TEN

Printing and Painting

Printing on fabric is another ancient art, developed in India and China well before it took off in Europe.

Printing probably began using found items dipped in dye or paint and pressed onto another surface in order to leave an imprint of it. From there decorations would have been carved or cut into the objects used for printing. These may have been stone and quite possible things like potatoes and other soft but perishable materials. Hands and fingers leave excellent marks too and these kinds of prints have been left on the walls of caves and rocks by our prehistoric ancestors.

The intricacy and sophistication of printed design would have been fairly contemporaneous with other develops in spinning and weaving techniques.

In India, China and Europe printing on cloth came before printing on paper. Paper wasn’t even introduced into Europe before the Middle Ages. Silk was a popular surface for printing onto.

The printing blocks were often made of wood and these were the first printing blocks to be used in China according to archaeological evidence. These early prints, surviving only in fragments were of flowers on silk and used three colours. Egyptian printed cloth evidence comes from a slightly later date, about 400 BC. India perfected the art of block printing executing exquisite designs of flowers in bright colours that caught the fancy of Europeans in the Eighteenth Century.

Ink suitable for adhering to the fibres of fabric is thickened with a substance called a colourant. This is to prevent the ink from running or bleeding into other parts of the fabric other than within the design. There are four main types of printing onto textiles. The first method is called direct printing and uses inks fixed with colourants so that the ink stays within its design.

The second method is to print a mordant only onto the cloth where the pattern is to go. When the ink is applied it will fix onto the fabric where the mordant is and nowhere else. The third method is the resist dye method which has already been discussed. Examples of this technique are batik, tie-dyeing and the like. The fourth method uses bleach to remove colour in a set design from fabric that has already received dye.

The Eastern countries successfully printed on textiles for centuries before the Europeans did. The art of block printing entered Europe through Spain via the Moors in the Twelfth Century as did so much technology. The European dyes were not as permanent as the Eastern ones and often ran marring the fabric. The problem was exacerbated by the need to wash items intended for clothing. Those that were for decorative purposes only tended to last longer.

Printing on fabric in England began in 1676 when a Huguenot refugee from France began his business in London. While England was new to the process it had already become established in mainland Europe and printers were becoming famous for their designs.

Calico printing had been popular in Germany and its neighbours for nearly a hundred years before it took off in England. The major influence on designs was France who had developed a reputation for the finest work in Europe.

The different methods of applying print to fabric are: woodblock, perrotine, engraved copperplate printing, roller printing, cylinder printing, or machine printing, stencil printing and digital textile printing.

Woodblock

Woodblock is the oldest form of printing on textile and has remained popular up until today. India was and still is a leading exponent of the art.

A piece of flat wood has a design drawn onto it and those parts that are not to be covered in ink are cut away. The raised design is then coated with ink via a roller, carefully placed onto the fabric and pressed down by hand or a clean roller to push the ink onto the fabric. In some countries it is transferred by hitting the printing block on the back with a wooden mallet.

One of the drawbacks of using wood blocks for printing is the wear of constant printing on the block. The finer details wear away quite quickly and so the quality of the print deteriorates over time. To overcome this problem the carved wood is often covered in metal, beaten into shape over the carved surface. If the design requires more than one colour a second and third block are prepared with the pattern cut into it. The designs must be lined up carefully so they integrate properly.

Perrotine printing

This is woodblock printing mechanised. What is the point of being able to produce yards and yards of woven fabric if it can’t be decorated in an easy and quick manner? All parts of textile production must try to match the others in time and quality.

Perrot lived in Rouen and it was his machine that revolutionised the printing of textile fabrics in 1834. Surprisingly the machinery never became accepted by the English although the rest of Europe embraced the new technology eagerly.

Engraved copperplate printing

Perhaps the Perrotine printing machine was never popular in England because they already had the engraved copperplate system. It was first used by Thomas Bell in 1770. The plates were fixed to a letterpress at first but then the cylinder press came into use. The cloth went around the cylinder which transferred the ink to the cloth. This method was difficult to line up the various colour plates.

Roller printing, cylinder printing, or machine printing

This was another of Thomas Bell’s inventions and he produced it in 1785. His first patent was for a machine that would print six colours at once but his design was not quite right and it was difficult to keep the six different plates in alignment. The problem was solved by Adam Parkinson in Manchester in the year of the machine’s patent, 1785. This time the machine proved successful.

Bell and Parkinson’s design could print 10,000 to 12,000 yards of fabric in a 10-hour day if only one colour was used. It was also excellent for reproducing any manner of designs. The main advantage was the precision in the matching up the different colours and its ability to print seamless repetitive motifs.

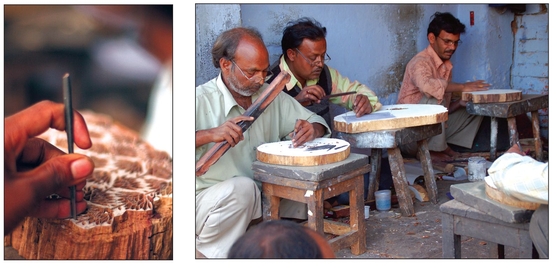

Woodblock cutters workshop, courtesy of David Dunning, Anokhi Hand Printing Museum, Jaipur, India.

Digital print of artist’s doll by Fiona McDonald, fabric printed by Spoonflower.

Preparing blocks for carving, courtesy of David Dunning, Anokhi Hand Printing Museum, Jaipur, India.

Carving woodblocks, photo courtesy of David Dunning, Anokhi Hand Printing Museum, Jaipur, India.

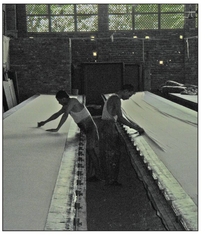

Preparing sheets of fabric for screen printing, photo courtesy of David Dunning, Anokhi Hand Printing Museum, Jaipur, India.

Stencil printing

Stencil printing is nearly as old an art as woodblock printing. They probably emerged in a very similar time frame and both were particularly close to the heart of the Japanese aesthetic.

Basically stencil printing involves a design cut out of a thin board, usually paper of metal. The cut away parts represent the coloured areas. The board is placed over the fabric and ink is brushed or rolled over the cut away design leaving a clear, hard edged design printed onto the fabric. The process can involve more than one colour plate. The subsequent plates being printed once the previous layer is dry.

A stencilling machine was built in 1894 by S.H. Sharp. The plate was made of thin steel and passed continuously over a cast iron cylinder as it turned. The fabric passed between the stencil and the roller and the ink was pressed onto it.

Screen printing

Screen printing was a development of stencil printing. Hand screen printing enjoyed a revival in the 1970s with people making their own silk screens. A design was cut in paper or card, laid over the fabric which lay flat on a table. Ink was applied with the aid of a squeegee; a length of tapered rubber held with a wooden block. The squeegee pulled the ink across the design in a smooth movement and left a clean print behind.

Screen printing has now become a highly technical business and companies print everything from road signs to tee shirts.

Screen printing, photo courtesy of David Dunning, Anokhi Hand Printing Museum, Jaipur, India.

Digital textile printing

Like everything else printing had to be digitalised. It is done through inkjet technology in the way computer printers print to paper. It is the most time efficient and accurate method of printing.

It is possible to upload images of an artist’s work onto a website called Spoonflower in the US and have that design printed onto fabric from the computer image.

Preparation of cloth for printing

Just as with dyeing, fabric must be prepared before it is ready to be printed. All finishes need to be removed and the fabric bleached to give it an all over quality of whiteness otherwise the pattern will appear altered. As with dyes certain mordents or fixatives need to be added or applied beforehand so the fabric will hold the colour fast and it won’t fade or run in the wash or in sunlight.

Painting

Hand painting fabric is a time consuming process. It is reserved for the most special fabrics and those who can afford such luxuries. The history of hand painting is another of those ‘lost in time’ stories but around 1000 BC a form of fabric painting emerged called ‘kalamkari’, which means pen work. The design was applied with a bamboo or date palm stick. A bundle of hair would be pushed into one end of the hollow stick to form a brush. At first the process was applied to cotton fabrics but it was later used on silk and other textiles. The technique was mainly used to depict Hindu religious and mythological scenes and deities.

From India the technique became accepted in China, Japan, Egypt and Greece. Europe came to it later.

- In the Americas the Incas and Aztecs had printing technology before they were invaded by the Spaniards

- In the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries European ladies would send finished dresses of silk and cotton to India or China to be hand painted. The idea behind sending a completed garment was that the design could be painted all over without any loss in the seams

- When the owners died they often bequeathed their costly dresses to the church to be made into articles such as kneelers and cushions