Introduction

Into the thickest wood, there soon they chose

The fig-tree, not that kind for fruit renowned,

But such as at this day to Indians known

In Malabar…

… those leaves they gathered, broad as Amazonian targe,

And with what skill they had, together sewed,

To gird their waist, vain covering if to hide

Their guilt and dreaded shame…

John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Book IX, 1100 – 1114

Was it really fig leaves mankind made its first clothes from? Stitched together with what? Perhaps vines or reeds even strands of Eve’s hair? Archaeologists would find the evidence for this earliest of textiles a bit insubstantial. Instead they have dug up fragments of spun thread, felted clothes, spinning and weaving tools, and pottery bearing the imprints of twisted threads. These artefacts can tell us many things about the history of the fabric we make and the clothes we wear.

Science has advanced to a stage where plant types can be identified from the indentation they have left in soft clay baked hard and buried for thousands of years.

Ancient trade routes have been traced to mark the comings and goings of goods and cultures across the world telling us that China traded silk fabric earlier than the official date given. We know that certain plants were unknown to Europeans although they readily wore clothes made from the cloth spun from the plant.

Textiles are an integral part of life. Terms used for the making of textiles, like weaving and spinning, are used for other aspects of our lives: we weave webs of intrigue and spin lies, cloak ourselves in mystery, knit our brows with worry and tie up loose ends of business. There are blankets of silence, sheets of rain and veils of mist. Textiles define who we are historically and culturally. Whether we live in a high rise city and wear the latest Paris fashions or we subscribe to older traditions away from the hustle and bustle of technology, we are still bound by certain taboos and beliefs about clothing. At funerals we don’t wear bright colours; traditionally it is black. Weddings are usually done in yards and yards of white silk, satin and lace but in some Asian countries you are married in red as a symbol of good luck and prosperity.

Boys are still dressed in blue, girls in pink. Red is still seen as a sexy and seductive colour (unless you are getting married in it). Blue and green should never be seen, though as it is the word green that rhymes with ‘seen’ then it could be any colour and green should never be seen.

The Greek Fates by Walter Crane.

The creation of textiles is so significant that they have infiltrated our myths and legends. The Ancient Greeks had a trio of goddesses called the Fates. Hesiod (ancient Greek poet) firstly called them the daughters of Night but then amended that to the daughters of Zeus and Themis and sisters of the Horae (goddesses of the seasons). Clotho was the spinner of the thread of human life. Lachesis measured the thread out into the person’s allotted life span and the third sister, Atropos would cut it at the moment of death.

Weaving was considered the proper skill for a woman and great pride was taken in it. Arachne, a mortal girl was an excellent weaver by human standards but she foolishly challenged the goddess Athena to a weaving contest. Arachne’s tapestry, for it was a woven picture, showed the gods in their disguises and trickery, dishonesty and unfaithfulness. The skill may have been there but it was not a diplomatic picture. Athena wove a picture of herself and Poseidon each striving for the domination of Athens and of course, pictures of stupid mortals who had challenged gods in the past – and lost. Arachne’s work was wonderful and had really challenged the goddess’s for skill and beauty. Athena destroyed it and assailed Arachne, beating her with her weaving shuttle. Arachne tried to hang herself but Athena, in a fit of remorse, turned her into a spider instead.

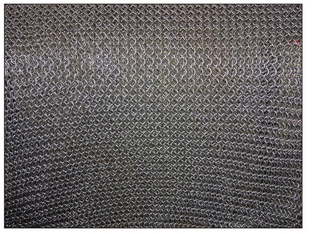

A chain mail shirt made of interlinked metal rings, but is it a textile?

Odysseus’s wife, the faithful Penelope used the weaving of her father-in-law’s shroud as an excuse to put off choosing a suitor and buying her husband more time to return home. Every day she would weave away and every night she would undo it all.

In China, silk and its production is wrapped in legend and secrecy. The wife of the mythical Yellow Emperor discovered silk when a cocoon fell into her cup of tea. From then on she became the goddess of silk cultivation, spinning and weaving.

Spinning and weaving have been dominated by women everywhere for domestic goods but in some places men had the job of weaving professionally. Knitting too was once undertaken by men: sailors and shepherds and men who knitted professionally. Knitting for home and children’s wear was women’s work.

The history of fabric is long and complicated. It is not just the history of the discovery of spinning and weaving thread out of different raw materials but it involves politics, travel, trade and war and society.

While I have tried to be thorough in my research there will, inevitably, be things missed from this book’s contents. For that I apologise and can only hope that what is within these pages stimulates the reader to digging further into this fascinating subject.